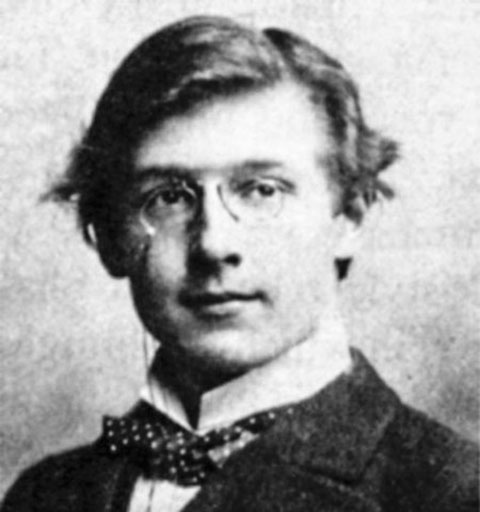

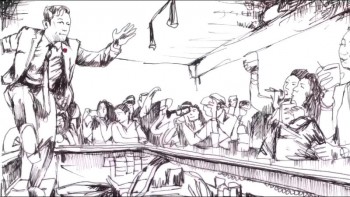

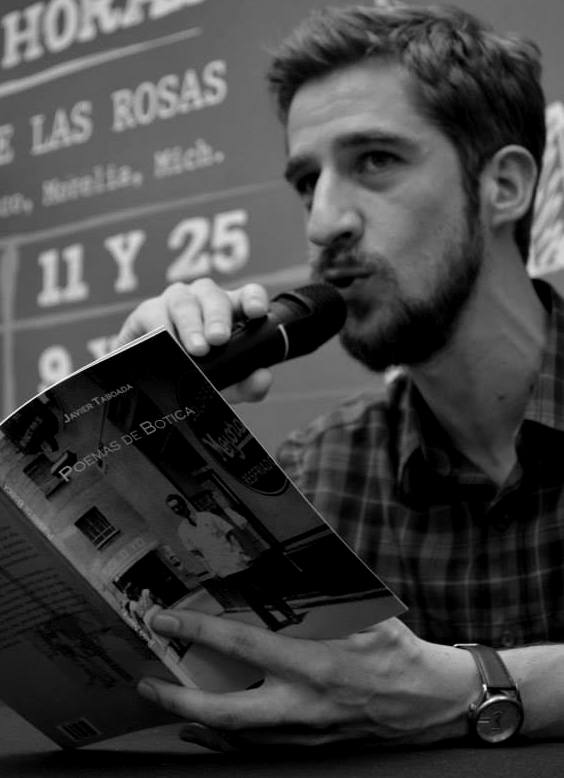

Henry Ainsley as Cuchulain in Yeats’s play At the Hawk’s Well, 1916.

Henry Ainsley as Cuchulain in Yeats’s play At the Hawk’s Well, 1916.

Photo by Alvin Langdon Coburn, by permission of George Eastman House.

x

On Christmas Day 1888, Oscar Wilde read to Yeats “The Decay of Lying,” later published in Intentions. That collection also includes “The Truth of Masks,” an essay on theatrical costumes that ends with Wilde’s declaration that “in art there is no such thing as a universal truth. A Truth in art is that whose contradictory is also true….It is only in art criticism, and through it, that we can realize Hegel’s system of contraries. The truths of metaphysics are the truths of masks.”{{1}}[[1]]“The Truth of Masks,” in The Artist as Critic: Critical Writings of Oscar Wilde, ed. Richard Ellmann (New York: Vintage, 1968), 432. Intentions (1891) also includes “The Critic as Artist.”[[1]] That final aphorism might, in style and content, have been written by Friedrich Nietzsche. In fact, Wilde’s fusion of Hegelian dialectic with Blake’s insistence on the fruitful clash of “Contraries” would have particularly resonated with W. B. Yeats after the turn of the century, when his reading of Wilde became aligned with his earlier study of Blake and his “excited” recent reading of Nietzsche, that “strong enchanter” whose thought, he believed, “completes Blake and has the same roots.”{{2}}[[2]]The Letters of W. B. Yeats, ed. Allan Wade (London: Rupert Hart-Davis, 1954), 379. This Yeatsian formulation may be one source of Harold Bloom’s theoretical conception (in Bloom’s term, tessera) of how a later poet, experiencing the “anxiety of influence,” imagines himself preserving his originality by “completing” a somehow truncated precursor.[[2]]

Yeats, 1932 by Pirie MacDonald.

Yeats, 1932 by Pirie MacDonald.

It might also be said that, in many ways, Nietzsche “completes” Wilde. “A truth in art is that whose contradictory is also true,” says Wilde. Writing two years later, Nietzsche, affirming art and life over moral/philosophical conundrums, tells us that, for well-constituted spirits, such an “opposition” as that between “chastity” and “sensuality” need not be “among the arguments against existence—the subtlest and brightest, like Goethe, like Hafiz, have even seen it as one more stimulus to life. Just such ‘contradictions’ seduce us to existence.”{{3}}[[3]]Genealogy of Morals, Third Treatise, §2. Nietzsche recalls and refutes Pauline dualism: “The flesh lusteth against the Spirit and the Spirit against the flesh; for these are contrary to one another” (Galatians 5:11). Citations from both the Genealogy and from Beyond Good and Evil are from Beyond Good and Evil / On the Genealogy of Morals, trans. Adrian Del Caro (Stanford: Stanford University Press, 2014). Here (pp. 287-88, as on p. 192, Beyond Good and Evil, Part 5 §198), Nietzsche couples his hero Goethe with the Persian poet Hafiz, who inspired Goethe’s final book of poems, West—Eastern Divan (1819).[[3]] Obviously, Nietzsche, that master perspectivist, strenuously denies (to again quote Wilde) any “such thing as a universal truth,” and, from The Birth of Tragedy on, he elevated art above philosophy, dismissing (in Twilight of the Idols) Kantian Idealism with its physical reality-denying doctrine of the ghostly “thing-in-itself” as “that horrendum pudendum of the metaphysicians!”{{4}}[[4]]Twilight of the Idols, “The Four Great Errors”: 3, in The Portable Nietzsche, ed. Walter Kaufmann (New York: Viking, 1954), 495. When Wilde says that “the truths of masks are the truth of metaphysics,” he means, my colleague Michael Davis astutely suggests, two things. The first is that “metaphysics is itself a mask,” adding that “Pater and Wilde are sharply suspicious of metaphysics precisely because” it is “beyond the physical,” and “both were intent on breaking down the mind/body distinction.” The same, of course, is true of Nietzsche. Though “mask” can be “something like a false face, a merely superficial ideological construction,” it is also the case “that masks themselves might have an alternative value to metaphysics, an alternative site for the construction of meaning that might even undo metaphysics and replace it with another sort of truth.” Again, Nietzsche would be in total agreement. My paper was initially written in response to a presentation on Wilde, Yeats, and the Mask by Jean Paul Riquelme (Le Moyne College, November 2, 2015), which both Michael and I attended. His observations cited above were in response to that first draft.[[4]] Nietzsche’s axiom, from Part III of the material posthumously published as The Will to Power, is well-known: “We possess art lest we perish of the truth” (§822; italics in original).{{5}}[[5]]The Will to Power, trans. Walter Kaufmann and R. J. Hollingdale (New York: Random House, 1967), 435. The full context is instructive. “For a philosopher to say, ‘the good and the beautiful are one,’ is infamy; if he goes on to add, ‘also the true,’ he ought to be thrashed. Truth is ugly. We possess art lest we perish of the truth.” If Nietzsche is criticizing the famous equation uttered by Keats’s hitherto silent Grecian Urn, “Beauty is truth, truth beauty,” he might be less surprised than most to find Keats asserting, in his own voice, the inferiority of “poetry” to “philosophy.” Again, the full context—the entry for March 19, 1819, in Keats’s extended journal-epistle to his brother and sister-in-law in America—is illuminating. “Though a quarrel in the streets is a thing to be hated, the energies displayed in it are fine; the commonest man shows a grace in his quarrel—by a superior being our reasoning[s] may take the same tone—though erroneous they may be fine. This is the very thing in which consists poetry; and if so it is not so fine a thing as philosophy—For the same reason that an eagle is not so fine a thing as a truth.” The Letters of John Keats, 1814-1821, 2 vols. ed. Hyder E. Rollins (Cambridge, Mass.: Harvard University Press, 1958), 2: 80-81. Like Blake, Nietzsche, and Yeats, Keats contrasts univocal truth, longed-for yet rejected, with the clash of contraries: the antinomies that generate “the energies” finely displayed, whether in a “quarrel” in the streets, in the dynamic tensions energizing a poem, or in what Yeats called the “quarrel with ourselves” out of which we make “poetry.”[[5]] Unsurprisingly, Nietzsche’s references to “masks” are in accord with Wilde’s equation of metaphysical truth with, or its replacement by, “the truths of masks.” Several of his formulations even help illuminate Wilde’s “pose.” Here are the half-dozen most crucial passages—all from Beyond Good and Evil, a book written in the same year (1885) as the original version of Wilde’s “The Truth of Masks”:

All that is profound loves a mask; the very profoundest things even have a hatred for images and likenesses. Shouldn’t the opposite be the only proper disguise to accompany the shame of a god?….Every profound spirit needs a mask; even more, a mask is continually growing around every profound spirit thanks to the constantly false, that is shallow interpretation of every word, every step, every sign of life he gives. (Part 2: §40).

Too noble for “Socratism,” Plato, the most daring of all interpreters,…took the whole of Socrates like a popular theme and folksong from the streets in order to vary it infinitely and impossibly, specifically into all his own masks and multiplicities. Spoken in jest, and moreover Homerically: just what is the Platonic Socrates if not “Plato in front, Plato in back, Chimaera in the middle” (Part 5: §190). [Nietzsche quotes the phrase in quotations in Greek, paraphrasing Homer on the tripartite chimaera (The Iliad VI: 181)].

That strength-cultivating tension of the soul,…its inventiveness and courage in enduring, surviving, interpreting…and whatever it was granted in terms of profundity, mystery, mask…: has all this not been granted…through the discipline of great suffering?….[in the] constant pressure and stress of a creative, shaping, malleable force…the spirit enjoys its multiplicity of masks…it is in fact best defended and hidden by precisely these Protean arts—this will to appearance, to simplification, to masks…. (Part 7: §225, 230)

Deep suffering makes noble; it separates. One of the most subtle forms of disguise is Epicureanism and a certain openly displayed courageousness of taste that takes suffering lightly and resists everything sad and profound. There are “cheerful people” who use cheerfulness because on its account they are misunderstood:—they want to be misunderstood. There are free impudent spirits who would like to conceal and deny that they are shattered, proud, and incurable hearts; and sometimes foolishness itself is the mask for an ill-fated, all-too-certain knowledge.—From which it follows that part of a more refined humanity is having respect “for the mask” and not practicing psychology and curiosity in the wrong place. (Part 9: §270)

Whoever you might be: what would you like now? What would help you recuperate? Just name it: what I have I offer to you! “To recuperate? To recuperate? Oh how inquisitive you are, and what are you saying! But give me, please—” What? What? Just say it!—“Another mask! A second mask!” (Part 9: §278)

Do people not write books precisely to conceal what they are keeping to themselves. Every philosophy also conceals a philosophy; every opinion is also a hiding place, every word also a mask. (Part 9: §289) {{6}}[[6]]Beyond Good and Evil, 41-42, 85-86, 129, 135, 185, 187-88, and 191-92.[[6]]

§

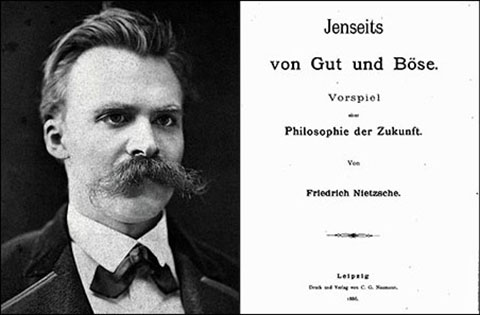

Friedrich Nietzsche Beyond Good and Evil.

Friedrich Nietzsche Beyond Good and Evil.

In letters to Lady Gregory and John Quinn (who had sent him in 1902 a new anthology of well-selected writings of the German philosopher), Yeats praised what he called, with remarkable tonal accuracy, Nietzsche’s “curious astringent joy” (Letters, 379), which he related to Blakean delight in energy and to Nietzsche’s own exuberant, life-affirming “respect for the mask.” In annotating selections from Nietzsche in the margins of that anthology, Yeats set up a diagram that explains much, if not all, of his subsequent thought and work, including his dramatic assertion three decades later (in “Vacillation”) that “Homer is my example and his unchristened heart,”{{7}}[[7]]From the seventh and final section of Yeats’s poetic sequence “Vacillation.” All of the poetry is cited, by title rather than page-number, from W. B. Yeats: The Poems, ed. and intro. Daniel Albright (London: Everyman’s Library, 1992).[[7]] and the assertion, three weeks before his death, when, filled with an “energy” he had despaired of recovering, he concluded, “When I put it all into a phrase I say, ‘Man can embody truth, but he cannot know it.’ I must embody it in the completion of my life” (Letters, 922).

Here is the diagram, based on Nietzsche’s major antitheses: Day vs. Night, Many vs. One, Dionysus vs. the Crucified, Homer vs. Plato/Socrates, Master Morality vs. Slave Morality; above all, the Nietzschean (and soon to be Yeatsian) distinctions between passionate, embodied being and cerebral, abstract knowing; and between power issuing in “affirmation” and ressentiment issuing in “denial.”

Night (Socrates/Christ) one god

Day (Homer) many gods

denial of self, the soul turned towards spirit seeking knowledge.

affirmation of self, the soul turned from spirit to be its mask & instrument when it seeks life.{{8}}[[8]]Scribbled in the margin of p. 122 of Nietzsche as Critic, Philosopher, Poet, and Prophet: Choice Selections from His Works, compiled by Thomas Common (London: Grant Richards, 1901). The book is now housed in the Special Collections Department of the library at Northwestern University (Item T.R. 191 N67n.). In that last letter, leading up to the assertion that “Man can embody truth but he cannot know it,” Yeats told Lady Elizabeth Pelham, “I know for certain that my time will not be long….In two or three weeks—I am now idle that I may rest after writing much verse—I will begin to write my most fundamental thoughts which I am convinced will complete my studies. I am happy, and I think full of an energy, of an energy I had despaired of. It seems to me that I have found what I wanted.” The letter was written on January 4, 1939. Yeats died, or “completed” his life, on January 28.[[8]]

Yeats’s diagram graphically demonstrates how “Nietzsche completes Blake.” The Romantic poet’s mature dialectic stresses polar inclusion: “Contraries are positive, a negation is not a contrary,” he incised in reverse at the beginning of Book the Second of Milton (Plate 30). But Blake is more dramatically antithetical in the far better-known passage in The Marriage of Heaven and Hell in which he introduced his oppositional Contraries, and their distortion by the “religious,” blind to the Blakean/Nietzschean dialectic “beyond” conventional “good” and “evil”:

Without Contraries is no progression. Attraction and Repulsion, Reason and Energy, Love and Hate, are necessary to Human existence. From these Contraries spring what the religious call Good & Evil. Good is the passive that obeys Reason. Evil is the active springing from Energy. Good is Heaven. Evil is Hell.{{9}}[[9]]Poetry and Prose of William Blake, ed. David V. Erdman, commentary by Harold Bloom (Garden City, NY: Doubleday, 1965), 34. This is Plate 3 of the Marriage; for the reverse-passage from Milton, see 128.[[9]]

Here is one source of the “energy” embodied in Yeats’s final letter and in the “frenzy” of “an old man’s eagle mind” in his late poem “An Acre of Grass.” In both cases, Blake is “completed” by “Nietzsche, whose thought flows always, though in an even more violent current, in the bed Blake’s thought has worn.”{{10}}[[10]]Essays and Introductions (London and New York: Macmillan, 1961), 130. The poem cited names Blake and alludes to the eagle-like soaring of Nietzsche’s “aeronauts of the intellect” (Dawn §542).[[10]] His Nietzsche-inspired diagram includes Yeats’s first recorded use of the term “mask.” A half-dozen years later, he wrote: “I think that all happiness depends on the energy to assume the mask of some other self; that all joyous or creative life is a rebirth of something not oneself.”{{11}}[[11]]Memoirs, ed. Denis Donoghue (New York: Macmillan, 1973), 191. Much of Yeats’s unpublished autobiographical material, including the important 1909 Diary, first appeared in this volume.[[11]] Yeats’s concept of the mask, as both a strategy for carrying on his quarrel with himself and an attempt to restore a lost Unity of Being, is identical to what he would later call, in “Ego Dominus Tuus” (1915), the “anti-self.” The last words of that dialogue between Hic and Ille (“This One” and “That One”) are given to Ille, whose position on mask and anti-self is so close to Yeats’s own that Ezra Pound (with his friend at Stone Cottage when the poem was written) famously observed that Ille should have been “Willie.” Seeking “an image, not a book,” Ille concludes that there is one, like yet unlike himself, who can “disclose/ All that I seek, and whisper it” in secret:

I call to the mysterious one who yet

Shall walk the wet sands by the edge of the stream

And look most like me, being indeed my double,

And prove of all imaginable things

The most unlike, being my anti-self.

Created “in a moment and perpetually renewed,” that mask of some “other self,” of “something not oneself,” is described in the 1909 diary entry as the “painted face” or “game” in which one “loses the infinite pain of self-realization.” It resembles Nietzsche’s “mask” concealing deep suffering, as well as Wilde’s “pose” and “mask,” artifices enabling the multiplication of personalities.

Yeats’s first public use of the term occurred in 1910, in “A Lyric from an Unpublished Play,” retitled “A Mask” three years later in ASelection from the Love Poetry of William Butler Yeats (Cuala Press). The first speaker in this three-stanza dialogue is anxious to discover whether his beloved’s dazzling “mask of burning gold/ With emerald eyes” conceals “love” or the “deceit” of an “enemy.” The reply: “It was the mask engaged your mind,/ And after set your heart to beat,/ Not what’s behind.” First worn by Decima in The Player Queen, this mask was initially inspired by Yeats’s mistress at the time, Mabel Dickinson. But since the poem appears in a slender volume (The Green Helmet and Other Poems, 1910) dominated by lyrics to and about Maud Gonne, and reappears in a selection from his “love poetry,” Yeats seems to want us to identify the masked figure with his Muse. To his anxious inquiry as to whether she is his “enemy,” she responds, “What matter, so there is but fire/ In you, in me?” Playing with fire is exciting but dangerous, especially if we are dealing with Maud Gonne, political activist, actress, and femme fatale. A Wildean Salomé in a mask, she is kin to that aloof young queen to whom the lowly jester, having had his “soul” and “heart” rejected, sacrifices his titular “cap and bells” in a beautiful early lyric that perversely flowers, four decades later, in Yeats’s Salomé-like plays for masks (especially A Full Moon in March) in which even colder queens demand severed heads, decapitation replacing the symbolic self-castration of “The Cap and Bells.”

“The Mask” was followed, five years later, by “The Poet and the Actress,” a prose-dialogue (unpublished until 1993) in which the dramatic poet urges an actress to cover “her expressive face with a mask.”{{12}}[[12]]First published in the expanded edition (1993) of David R. W. B. Clark’s Yeats and the Theatre of Desolate Reality (Dublin: Dolmen Press, 1965).[[12]] The Poet is echoing the man Yeats considered “the greatest stage inventor in Europe,” Gordon Craig, who had collaborated in Abbey Theatre productions for several years beginning in 1909, and who insisted, in the first (March 1908) issue of his magazine, The Mask, that “human facial expression is for the most part valueless…Masks carry conviction… The face of the actor carries no such conviction; it is over-full of fleeting expression—frail, restless, disturbed, and disturbing.” Yeats also knew Craig’s “A Note on Masks,” published the same year Yeats wrote his poem “The Mask.”{{13}}[[13]]Quoted in Denis Bablet, Edward Gordon Craig (London: Heinemann, 1966), 110. Yeats had been aware of Craig’s work since 1901, when he saw his celebrated production of Purcell’s Dido and Aeneus. For the appraisal of Craig as Europe’s “greatest stage inventor,” see Uncollected Prose by W. B. Yeats, 2 vols. ed. John P. Frayne and Colton Johnston (New York: Columbia University Press, 1976), 2:393.[[13]]

Craig sought a theater “purged of hideous realism,” and he and Yeats agreed that the Ibsen school of “realism” must be replaced by a theatre of masks if artists were to do justice to what Yeats called in this long-unpublished dialogue, the “battle [that] takes place in the depths of the soul.” It was a conviction realized in Yeats’s own mask-plays, combining Japanese Noh drama with the theatrical insights of Wilde and of Craig, who stage-designed Yeats’s Cuchulain play At the Hawk’s Well, featuring costumes and masks by Edmund Dulac. Launching his “Phrases and Philosophies for the Use of the Young” (1894), Wilde asserted that “The first duty in life is to be as artificial as possible. What the second duty is no one has as yet discovered.”{{14}}[[14]]The Artist as Critic, ed. Ellmann, 433.[[14]] He was being more than witty. Yeats agreed with Wilde and Craig, as with Nietzsche, that the purpose of artifice, specifically the wearing of a mask, was not merely to conceal, but to reveal deeper and immutable truths: gathering the audience, to adapt a famous phrase from “Sailing to Byzantium,” into “the artifice of eternity.”

There was also the theater of Eros. In diary notes written after the long-delayed sexual consummation (in Paris, in December 1908) of his love for Maud Gonne, Yeats proclaimed that, in “wise love,” both partners may achieve their masks: “each divines the high secret self of the other and, refusing to believe in the mere daily self, creates a mirror where the lover or the beloved sees an image to copy in daily life. Love also creates the Mask” (Memoirs, 144-45). But that night in Paris had been followed by a morning-after note in which Maud told Yeats she was praying he would be able to “overcome” his “physical desire,” and expressing the wish to revert to their old mystical marriage, an intimate but non-sexual relationship. His immediate grief triggered a mature reassessment, which included sublimation in the form of the century’s greatest body of love poems and affairs with “others.” After the execution of Maud’s estranged husband, Easter Rising leader John MacBride, Yeats had revived his hope of a sustained relationship with Maud: a dream that ended definitively with her final refusal of marriage, physical or mystical, in June 1917. Four months later, he married Georgie Hyde-Lees.

Of course, that “perverse creature of chance” (in “On Woman,” the first of the Solomon and Sheba poems) would continue to fascinate Yeats; and the acceptance of the attendant anguish plays a major part in his poetic embrace of Nietzschean eternal recurrence, both in “On Woman,” where the lovelorn speaker chooses to come “to birth again,” and in “A Dialogue of Self and Soul,” where the choice to “live it all again/ And yet again,” means plunging once more into “that most fecund ditch of all,/ The folly that man does/ Or must suffer, if he woos/ A proud woman not kindred of his soul.”{{15}}[[15]]The thought might make you “throw yourself down and gnash your teeth,” says Nietzsche’s demon in the passage introducing the thought-experiment or ordeal of eternal recurrence. But have you, even “once,” experienced a “moment” so “tremendous” that you “fervently craved” it “once more” and “eternally?” The Gay Science, trans. and ed. Walter Kaufmann (New York: Vintage, 1974), §341. Echoing that passage, the Yeatsian speaker in “On Woman” wants, should he come “to birth again,” to find “what once I had/ And know what once I have known.” He will accept sleeplessness, “gnashing of teeth, despair;/ And all because of some one/ Perverse creature of chance,/ And live like Solomon / That Sheba led a dance.” In the draft of a Solomon and Sheba poem published 80 years after it was written, Yeats depicts himself as a folly-driven Solomon perplexed by the “labyrinth” (a code-word for Maud) of Sheba’s mind. Will he be proven a wise man or “but a fool.” (See Yeats Annual 6: [1988] 211-13.)[[15]] As Yeats noted, paraphrasing Blake’s “old thought” (in both “Anima Hominis” and in a later letter glossing the erotic tension in “Crazy Jane Grown Old Looks at the Dancers”), it may be that “sexual love” is “founded on spiritual hate” (Memoirs, 336, Letters, 758). Indeed, the “mirror where the lover or beloved sees an image” will return to maliciously threaten the Self in the very poem in which Maud is depicted as “not kindred of my soul.”

§

The power of Yeats’s best poetry springs from the dialectical tension between “contraries” (Hegelian, Blakean, Wildean, Nietzschean): “Contraries” without which, as Blake said in his most dialogical work, The Marriage of Heaven and Hell, there is “no progression.” At the heart of this Yeatsian antinomy is the gap between the “bundle of accident and incoherence that sits down to breakfast,” as he put it in the “Introduction” to the projected deluxe edition of his work—and the self dramatically “reborn”: the Mask, italicized and defined (in the 1937 edition of A Vision) as Will’s “opposite or anti-self.”{{16}}[[16]]Essays and Introductions, 509; A Vision (London: Macmillan, 1962). For the “Rules for Discovering True and False Masks,” see 90-91. Each Phase in Yeats’s intriguing if bizarre lunar scheme has, along with its Will, Creative Mind, and Body of Fate, its Mask, True and False. Wilde is located, along with Byron and “a certain actress,” in Phase 19, “the phase of the artificial, the fragmentary, and the dramatic” (148). Nietzsche is the solitary occupant of Phase Twelve, that of “The Forerunner” and the hero (126).[[16]] The internal Yeatsian drama of masks and personae is played out in interactions and oppositions beginning with St. Patrick and Oisin (The Wanderings of Oisin, 1889); Hic and Ille in “Ego Dominus Tuus”; Aherne and Robartes (‘Nineties’ personae revived for “The Phases of the Moon”); or gentler oppositions between the latter and the young girl in “Michael Robartes and the Dancer,” or between the blonde beauty and the Yeatsian old man in “For Anne Gregory.” The agon continues in the crucial “Dialogue of Self and Soul” and, in the Crazy Jane sequence, in the debates between the repressed and repressive Bishop and Jane, who dialectically double-puns that “Nothing can be sole or whole/ That has not been rent.” These tensions persist to the end. Proudly rehearsing his earthly and imaginative accomplishments in his final years, Yeats is challenged—“‘What then?’ sang Plato’s ghost, ‘what then?’”—by a more formidable spokesman of the spiritual Otherworld than the Soul in “Dialogue,” let alone Jane’s hypocritical Bishop. Even in the face of death, as we’ll see, the Yeatsian Man has to contend with his own sardonic Echo.

There are also singular anti-selves, impulsive figures such as lusty Red Hanrahan and the ghost of Leo Africanus, a 16th-century Moor conjured up by Yeats in séances beginning around 1909. Yeats imagined this adventurer and travel writer being “drawn to me because in life he had been all undoubting impulse,” while “I was doubting, conscientious, and timid.” There are several parallels having to do with the Gregorys and Coole Park. Among the “excellent company” frequenting the Great House was “one,” Yeats himself, “who ruffled in a manly pose/ For all his timid heart” (“Coole Park, 1929”), a description that illuminates several poems in The Wild Swans at Coole, as well as his private contrast between himself and the Gregorys.

On a rare occasion when his defense of Lady Gregory against attack had struck mother and son alike as inadequate, Yeats tried, in a letter to Robert, to explain. Because of his analytic mind, with its tendency “to exhaust every side” of a subject, he had lost the capacity for “instinctual indignation.” His “self-distrustful analysis of my own emotions” had, Yeats said, “destroyed impulse.” On this point, he found his stance “unreconcilable” with that of the Gregorys, whose instinctual “attitude toward life” had, like Maud Gonne’s, that “purity of a natural force” Yeats admired, envied—and left to others to embody.{{17}}[[17]]In this draft letter to Robert (Memoirs, 252-53, 257), which may or may not have been sent, Yeats describes this as the “one serious quarrel” he ever had with Lady Gregory. In “The People,” another poem in The Wild Swans at Coole, Yeats similarly contrasted himself, “whose virtues are the definitions/ Of the analytic mind,” with the impulsive Maud Gonne, who has not “lived in thought but deed” and so has “the purity of a natural force.” The poems alluded to later in this paragraph—“The Wild Swans at Coole,” “In Memory of Major Robert Gregory,” and “An Irish Airman Foresees his Death”—are the opening three poems in The Wild Swans at Coole, their bleak tone reflecting both the contrast with heroic Gregory and Yeats’s despondency in the aftermath of Maud’s rejection of his fourth and final marriage proposal.[[17]] And there is, of course, the ambivalent comparison with Robert Gregory himself: the Irish airman whose “lonely impulse of delight” made him one of those heroic men of action who “consume/ The entire combustible world in one small room,” while others, like sedentary Yeats, tediously “burn damp faggots” or count swans on the lake while shuffling among the autumnal leaves littering the estate Robert Gregory would have inherited had he not met his “fate/ Somewhere among the clouds above.”

But Yeats’s central hero—his most formidable opposite, mask, or anti-self—is the Celtic Achilles, impulsive Cuchulain, representing “creative joy separated from fear” (Letters, 913). Resurrected from ancient epic, he became the protagonist of a cycle of five Yeats plays and of several poems. The last of those plays, The Death of Cuchulain, and his final poem on the hero, the terza rima masterpiece “Cuchulain Comforted,” were written in the shadow of Yeats’s own impending death. In the poem, the slain hero is now in the Underworld; hence the Dantesque stanza-form, repeated in Eliot’s adaptation of terza rima in the encounter with the largely Yeatsian “compound ghost” in “Little Gidding.” The hero, nameless except in the poem’s title, lays down his sword to take up needlework; he joins a communal sewing bee, stitching shrouds among his polar opposites, “convicted cowards all.” He is soon to join them in their transformation as well. Those shrouded spirits, already described as “birdlike things,” suddenly sing, but “had nor human tunes nor words,/ Though all was done in common as before [.]/ They had changed their throats and had the throats of birds.” On an autobiographical level, this role-reversal, almost gender-reversal, by Yeats’s solitary, hyper-masculine, and defiantly non-conformist warrior-hero, tends to confirm the essential truth of one of Yeats’s most revealing self-appraisals, or un-maskings: his reference to himself, already cited, as “one who ruffled in a manly pose/ For all his timid heart.” Even here, in that birdlike “ruffling,” there is a faint vestige of the mask of the hawk-god, Cuchulain.

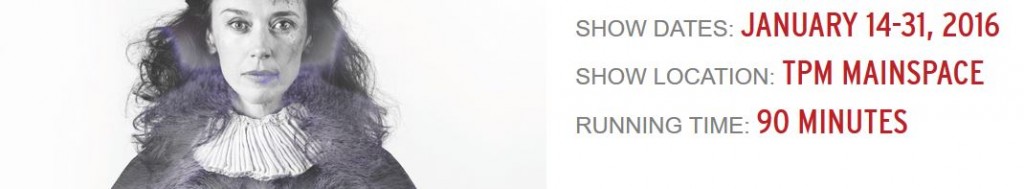

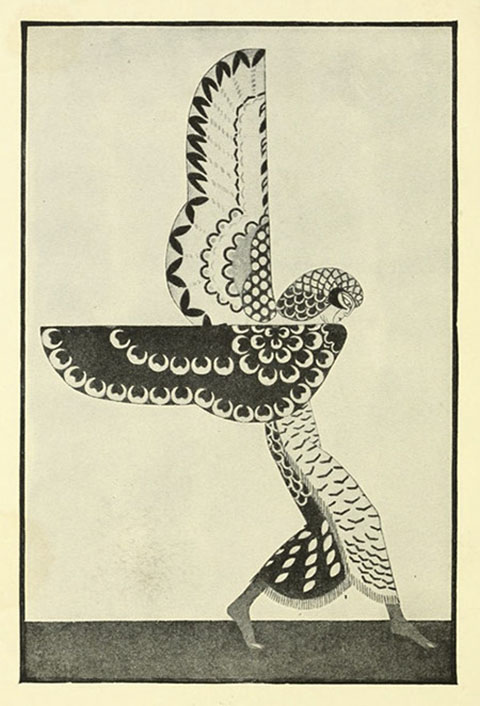

Edmund Dulac design for costume and mask for At the Hawk’s Well.

Edmund Dulac design for costume and mask for At the Hawk’s Well.

Illustration from Four Plays for Dancers, 1921.

There is a similar revelation of the sensitive man under the heroic mask at the conclusion of a dialogue-poem already referred to, “Man and the Echo.” Standing in the cleft of a mountain and confronting imminent death, the Man hopes to “arrange all in one clear view,” and, “all work done,” prepare to “sink at last into the night.” But the world is too contingent for such well-laid plans. Echo’s ominous repetition, “Into the night,” raises more, and more metaphysical, questions: “Shall we in that great night rejoice?/ What do we know but that we face/ One another in this place?” Finally, all philosophic thoughts stop together, interrupted by an intervention from the physical world, and a reminder of the suffering and radical finitude the poet shares with all mortal creatures:

But hush, for I have lost the theme,

Its joy or night seem but a dream;

Up there some hawk or owl has struck

Dropping out of sky or rock,

A stricken rabbit is crying out

And its cry distracts my thought.

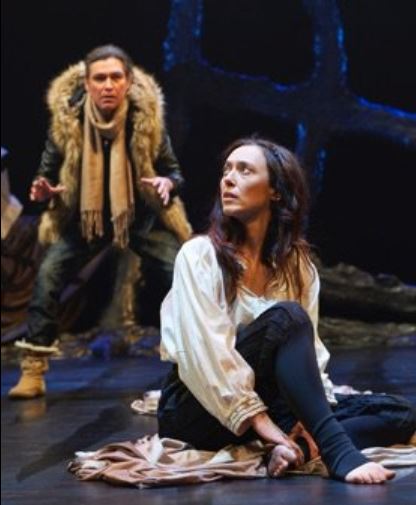

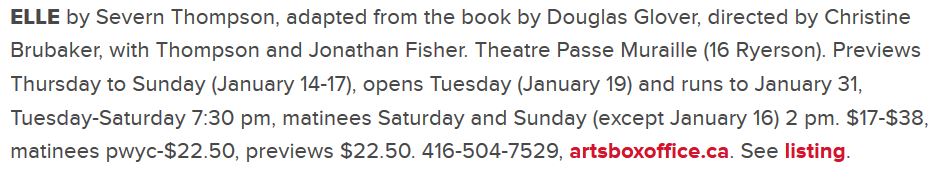

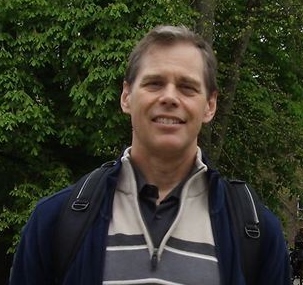

Dancer in costume designed by Dulac, At the Hawk’s Well, 1916.

Dancer in costume designed by Dulac, At the Hawk’s Well, 1916.

Photo by Alvin Langdon Coburn, by permission of George Eastman House.

In some poets, such a conclusion might be sentimental. But it is precisely Yeats’s frequent deployment, especially after encountering Nietzsche at the turn of the century, of a heroic, pitiless mask that makes this moment so poignant. For here Yeats identifies—not, as he so often had, with the perspective of the predatory bird (with Cuchulain, son of that “clean hawk out of the air”)—but with the death-cry of a defenseless, pitiable victim. One recalls chastened Lear on the storm-beaten heath (“Take physic, pomp…. I have ta’en too little notice of this”) and Nietzsche’s final breakdown in Turin, tearfully embracing a beaten coach-horse.{{18}}[[18]]No sooner had he famously embraced the horse being viciously whipped than Nietzsche collapsed in the street: a collapse that proved mentally permanent. Yeats’s Nietzschean critique of “pity” as inappropriate to art explains his two most notorious public rejections: of Sean O’Casey’s The Silver Tassie for the Abbey Theatre, and of Wilfred Owen’s war-poetry from the Oxford Book of Modern Verse.[[18]]

§

“Man and the Echo” (1938) is the last, and one of the greatest, in Yeats’s long litany of dialogue-poems. Given the tension between the provisional nature of his commitments and his attraction to a form of polarity that generates power, it is unsurprising that Yeats was repeatedly drawn to poems (over thirty in number, great and small) that take the traditional form of debate or dialogue, necessarily exercises in masking. “The Mask” itself, a brief early instance, would be followed by much more elaborate examples, beginning with “Ego Dominus Tuus.” Later Yeats presents us with more dramatic oppositions and dialogue-poems, such as the Crazy Jane and Man and Woman Young and Old sequences, and, along with “Man and the Echo,” the most resonant of them all, “A Dialogue of Self and Soul” (1927) and the appropriately-titled “Vacillation” (1931-32). That poetic sequence begins by explicitly laying out the antinomial tension between contraries that had, in the wake of his completion of Blake by Nietzsche, supplanted Yeats’s hitherto univocal vision. “All things fall into a series of antinomies in human experience” (A Vision, 193): an abstraction blooded in the opening lines of “Vacillation”:

Between extremities

Man runs his course;

A brand, or flaming breath

Comes to destroy

All those antinomies

Of day and night;

The body calls it death,

The heart remorse.

But if these be right

What is joy?

It turns out (as in “Lapis Lazuli” and its lesser companion-poem, “The Gyres”) to be a Nietzschean “tragic joy,” based on the antinomies (“Night/Day,” “Christ/Homer”) set up three decades earlier in the margins of that Nietzsche anthology. In the debate in section VII of “Vacillation” (“A Dialogue of Self and Soul” in stichomythia), the defiant Heart refuses the purifying fire proffered by the spiritual Soul: “Look on that fire, salvation walks within.” Temporally and thematically wrenching Augustinian Christianity into a pagan and heroic context, Heart, a “singer born” who indignantly refuses to be “struck dumb in the simplicity of fire,” responds: “What theme had Homer but original sin?” And, in his own voice, inflected by Nietzsche, Yeats asserts in the final movement of “Vacillation” that “Homer is my example and his unchristened heart.”

But not even that resonant proclamation ends the antinomy. The poem’s final movement had begun with a question: “Must we part, Von Hügel, though much alike, for we/ Accept the miracles of the saints and honour sanctity?” The spiritual side of the usual Yeatsian antinomy is here represented by the Catholic theologian and mystic, Friedrich, Baron von Hügel, whose The Reality of God and Religion and Agnosticism had been posthumously published in 1931. Yeats might be as moved by the miraculous state of the body of St. Theresa, which “lies undecayed in tomb,” as he is by the preservation of “Pharoah’s mummy,” yet

I—though heart might find relief

Did I become a Christian man and choose for my belief

What seems most welcome in the tomb—play a predestined part.

Homer is my example and his unchristened heart.

The lion and the honeycomb, what has Scripture said?

So get you gone, Von Hügel, though with blessings on your head.

Citing Samson, who took honey from the bees swarming in the body of the slain lion, Yeats is adapting the Bible (Judges 14:14) to make his own recurrent point that it is “only out of the strong” that sweetness comes. The poem’s final line—a patronizing yet courteous, benign dismissal of the spiritual spokesman—was cited by Yeats in a 1932 letter to Olivia Shakespear, his first lover (“young/ We loved each other and were ignorant”) and most intimate lifelong correspondent. Having just reread his entire canon, and thinking of the old debate between Oisin and St. Patrick and of the more recent one between Heart and Soul in “Vacillation,” Yeats clarified what he now considered the power-producing tension dominating all his poetry: “The swordsman throughout repudiates the saint, but not without vacillation. Is that perhaps the sole theme—Usheen and Patrick—‘so get you gone Von Hugel though with blessings on your head’?”(Letters, 798){{19}}[[19]]The Olivia-poem cited is “After Long Silence.” In his attitude toward von Hügel, Yeats may be recalling another statement in The Marriage of Heaven and Hell, almost as famous as, and allied with, “Without Contraries is no progression.” This statement, “Opposition is true Friendship,” at the end of Plate 20 (Poetry and Prose, p. 41), is painted out in some copies of the Marriage, perhaps because Blake did not want readers to think he was reconciling with his opponent in the immediately preceding passage: the debate between himself and the conventionally religious “Angel” in the fourth and most important “Memorable Fancy.” That debate had ended with the Blakean figure declaring, “we impose on one another, & it is but lost time to converse with you whose works are only Analytics.” Yeats doesn’t want to reconcile with von Hügel, but his tone confirms that opposition need not preclude friendship.[[19]]

Yeats’s principal Celtic “swordsman” is Cuchulain rather than Oisin; but no matter, Saint and Swordsman emerge as Yeats’s ultimate antinomial “contraries,” and his most sustained “masks.” The blessing on von Hügel’s head is a terminal benediction by a man who, like von Hügel, believed in miracles, and who had also experienced such privileged moments as the epiphany recorded in section IV of “Vacillation,” when his “body”—that of a fifty-year-old poet sitting “solitary” in a “crowded London shop”—“of a sudden blazed,” and “twenty minutes more or less/ It seemed, so great my happiness,/ That I was blessèd and could bless.”

It seems to me no accident that in “Little Gidding,” his masterpiece and the very poem in which he encounters Yeats’s ghost, T. S. Eliot also alludes to Yeats’s dismissed saint, echoing von Hügel’s “costingness of regeneration” in referring to the cost (“not less than everything”) of refinement in spiritual fire. Eliot knew that, despite Yeats’s momentary sense that he was “blesséd and could bless,” everything was a price too high to be paid by the older poet, a “singer born” who refused (in section VII of “Vacillation”) to be consumed in the “simplicity” of spiritual “fire.” This is only one of several even more obvious allusions to “Vacillation” in the course of Eliot’s encounter with the “familiar compound ghost” in Part II of “Little Gidding.” That the recently dead Yeats plays the predominant part in that “compound” is demonstrated by both the drafts and the final version of this magisterial passage, as well as by Eliot’s explicit remarks in several letters. Nevertheless, it may be said that, as presented in the ghost-encounter in this final poem of Four Quartets, Yeats and Eliot emerge as one more example of opposites “united in the strife that divided them” (“Little Gidding,” III, 174).{{20}}[[20]]The correspondents in the letters referred to are John Hayward, Maurice Johnson, and Kristian Smidt. For details, see Helen Gardner, The Composition of “Four Quartets” (New York: Oxford University Press, 1978), 64-67. And see below, n. 29.[[20]]

§

Four years before “Vacillation,” in “A Dialogue of Self and Soul,” My Self, anticipating the antinomies (day/night, death/remorse) set up at the outset of “Vacillation,” chooses “emblems of the day against the tower/ Emblematical of the night.” Yeats’s emblem of vital and erotic life is again a sword, but this time, a Japanese ancestral sword (the gift of an admirer, Junzo Sato) wound and bound in female embroidery. In his magnificent, life-affirming peroration, the Self embraces the entangled joy and pain of Nietzschean eternal recurrence: “I am content to live it all again/ And yet again.” Having read Nietzsche’s The Dawn, Yeats adopted the “privilege” of the autonomous self in that book “to punish himself, to pardon himself,” so that “you will no longer have any need of your god, and the whole drama of Fall and Redemption will be played out to the end in you yourself.”{{21}}[[21]]§437, §79. The volume Yeats knew as The Dawn (a book that demonstrably influenced other poems as well, most notably “An Acre of Grass” and its companion-poem, “What Then?”) has been best and most recently translated by R. J. Hollingdale as Daybreak: Thoughts on the Prejudices of Morality (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1982). I quote pp. 186-87 and 48 of this edition.[[21]] The Yeatsian Self, spurning Soul’s ultimate doctrinal declaration, “only the dead can be forgiven,” a grim passivity that turns his own tongue to “stone,” asserts the right to

Measure the lot, forgive myself the lot!

When such as I cast out remorse

So great a sweetness flows into the breast

We must laugh and we must sing,

We are blest by everything,

Everything we look upon is blest.

Reversing a venerable tradition (running from Plato and Cicero through Marvell) of debates between Body and Soul, flesh and spirit, the Self is triumphant, reflecting the “movement downwards upon life, not upwards out of life,” Yeats had adopted in the first years of the new century. It was a movement he associated—in the remarks to Ezra Pound prefacing AVision—with “a new divinity”: Sophocles’ chthonic Oedipus, who “sank down body and soul into the earth,” an earth “riven by love,” in contrast to, or in “balance” with, Christ who, “crucified standing up, went into the abstract sky soul and body.” (Letters, 63, 469; A Vision, 27-28). But since My Soul is also a part of Yeats, the “Dialogue” ends in a state of self-forgiving secular beatitude, including the “joy” sought in “Vacillation,” with the Self employing the spiritual terms Soul would monopolize.

The Soul had summoned Self to imbibe from the Plotinian “fullness” that “overflows/ And falls into the basin of the mind,” and so “ascend to Heaven.” Self, embracing a pagan affirmation of life, began his peroration by defying Neoplatonic Soul, punningly declaring that, “A living man is blind and drinks his drop.” In effect, Nietzschean Self “completes” the climactic cry of Blake’s Oothoon, heroine of Visions of the Daughters of Albion: “sing your infant joy!/ Arise and drink your bliss, for every thing that lives is holy!”—a Blakean “praise of life” Yeats specifically connects with “Nietzsche…at the moment when he imagined the ‘Superman’ as a child.”{{22}}[[22]]Autobiographies (London: Macmillan, 1955), 474-75. In epitomizing Blake’s “praise of life—‘all that lives is holy’,” Yeats is fusing passages. Along with Oothoon’s chant (final plate, Visions of the Daughters of Albion), he is recalling the choral conclusion of The Marriage of Heaven and Hell: “For every thing that lives is Holy!” And his phrase “praise of life” also seems to echo Blake’s America, Plate 8:13: “For every thing that lives is holy, life delights in life.” (The Poetry and Prose of William Blake, 50, 44, 53). John Steinbeck, who puts the slightly misquoted line, “All that lives is holy,” in the mouth of his Blakean-Whitmanian prophet Jim Casy in Chapter 13 of TheGrapes of Wrath, was probably thinking only of the finale of The Marriage of Heaven and Hell.[[22]] Hating the “same dull round” of all forms of cyclicism, Blake would have rejected Nietzsche’s doctrine (or thought experiment) of eternal recurrence as an anti-humanistic nightmare. But Yeats forces the “completion” on the basis of the energy and childlike joy in life shared by Blake and Nietzsche’s Zarathustra, prophet of the Übermensch.{{23}}[[23]]When Zarathustra jumps “with both feet” into “golden-emerald delight,” he also jumps into a cluster of images and motifs we would call “Yeatsian,” primarily but not only because of Self’s laughing, singing self-absolution, echoing Blake’s “every thing that lives is holy”:

In laughter all that is evil comes together, but is pronounced holy and absolved by its own bliss; and if this is my alpha and omega, that all that is heavy and grave should become light, all that is body, dancer; all that is spirit, bird—and verily that is my alpha and omega: oh, how should I not lust after eternity and the nuptial ring of rings, the ring of recurrence? (Thus Spoke Zarathustra III:16)

Along with Self’s final chant, one recalls the Unity of Being projected in the final stanza of “Among School Children,” an antinomy-resolving state where “body is not bruised to pleasure soul,” and we no longer “know the dancer from the dance.” And Zarathustra’s transformation of “spirit” into “bird” will remind us of the natural and golden birds of the Byzantium poems and the final transfiguration of Yeats’s central hero—in both The Death of Cuchulain and “Cuchulain Comforted”—into a singing bird.[[23]] The fusion, anticipating the more personal epiphany in “Vacillation,” enables Yeats to conclude that “We are blest by everything,/ Everything we look upon is blest.” The religious vocabulary conventionally reserved for the spiritual spokesman becomes, in the unchristened mouth of Self, a rhapsodic chant. For, as Yeats had memorably observed in the “Anima Hominis” section of Per Amica Silentia Lunae, “we make out of the quarrel with others, rhetoric, but of the quarrel with ourselves, poetry.”{{24}}[[24]]Mythologies (London and New York: Macmillan, 1959), 331.[[24]]

In this psychomachia, this antinomial conflict between opposing aspects of the self, Yeats also completes Wilde with Nietzsche, whose stress on antithetical conflict, penchant for images of combat, and sense of discipline added hardness and virility to what Yeats had inherited from Wilde concerning mask, artifice, and pose. Thus Nietzsche helped forge the “mask” we think of as most distinctively Yeatsian: the poet’s own version of what he called in A Vision Nietzsche’s “lonely, imperturbable, proud Mask” (128). It is a Homeric mask, as Robartes makes clear in “The Phases of the Moon,” Yeats’s poetic synopsis of his lunar System. Eleven phases “pass, and then/ Athena takes Achilles by the hair,/ Hector is in the dust, Nietzsche is born,/ Because the hero’s crescent is the twelfth.”

And yet, as we’ve seen, in two of his latest and greatest poems, “Man and the Echo” and “Cuchulain Comforted,” the second describing the transformation of his own proud hero and anti-self, Yeats, who had earlier assumed the masks of Crazy Jane and a Woman Young and Old, also revealed a gentler, feminine, almost androgynous side of himself—perhaps what we might call the Wilde(r) side. It is no accident that Yeats’s greatest composite symbol, Sato’s sword, is not only sheathed, but protected and adorned by “That flowering, silken, old embroidery, torn/ From some court-lady’s dress and round/ The wooden scabbard bound and wound,” in effect, reenacting the rondural structure of the Winding Stair (as literal staircase in Yeats’s Norman tower, emblem, and book-title) as well as the spiral symbolic of both Goethe’s Eternal Feminine and Nietzsche’s Eternal Recurrence.

§

Discussing the relation between “discipline and the theatrical sense” in Per Amica Silentia Lunae, Yeats outlined the “condition for arduous full life”:

If we cannot imagine ourselves as different from what we are and assume that second self, we cannot impose a discipline upon ourselves, though we may accept one from others. Active virtue as distinguished from the passive acceptance of a current code is therefore theatrical, consciously dramatic, the wearing of a mask.{{25}}[[25]]Mythologies, 334, and Autobiographies, 469.[[25]]

Yeats here combines the Blakean Contraries (“the active springing from Energy” preferred to “the passive that obeys Reason”) with the theatrical language of “The Truth of Masks.” But Yeats never acknowledged Wilde’s use of the term “mask.” Perhaps because, for all his importance as a precursor, Wilde had to be “completed” with Blake and Nietzsche, and with Yeats’s own theories, classical and occult, of hero and Daimon. In the “Anima Hominis” section of Per Amica Silentia Lunae, Yeats writes, “I thought the hero found hanging upon some oak of Dodona an ancient mask…that when he looked out of its eyes he knew another’s breath came and went within his breath upon the carven lips.” He tells us that “the Daimon comes not as like to like but seeking its own opposite”; that unity is achieved “when the man has found a mask whose lineaments permit the expression of all the man most lacks” and “perhaps dreads”; and that “the poet finds and makes his mask in disappointment, the hero in defeat.” (Mythologies, 335-37)

There are many sources (psychological, theatrical, occult) for Yeats’s inter-related but shifting aesthetic and ethical theories about what he called “the Mask.”{{26}}[[26]]For a full discussion of the subject, see the essays gathered in Yeats Annual 19 (2013), titled The Mask, especially Warwick Gould’s long and characteristically thorough study, “The Mask before The Mask.”[[26]] In “The Decay of Lying,” Wilde had asserted that “truth is entirely and absolutely a matter of style,” and Yeats insists that “Style, personality (deliberately adopted and therefore a mask), is the only escape” from the heat of “bargaining” and the “money-changers” (Memoirs, 139; Autobiographies, 461). Contemporary “reality” and the merely individual may be transcended by tradition, by elemental, ideal art, “those simple forms that like a masquer’s mask protect us with their anonymity.” A quarter-century earlier, in “The Tragic Theatre” (1910), Yeats had celebrated, as another “escape” from the “contemporary,” the expression of “personal emotion through ideal form, a symbolism handled by the generations, a mask from whose eyes the disembodied looks, a style that remembers many masters.”{{27}}[[27]]Yeats’s Preface to his early essays, collected in 1934 as Letters to the New Island, xiii. (The volume was re-published in 1989 (ed. George Bornstein and Hugh Witemeyer) in The Collected Works of W. B. Yeats. “The Tragic Theatre,” in Unpublished Prose 2:388.[[27]] The most recent of the masters to swim into Yeats’s ken at just the right time to shape his new style was “that strong enchanter, Nietzsche.”

In prose and in many poems and plays written after 1903, Yeats adds to his arsenal Nietzsche’s theory of the mask, as well as his concepts of self-overcoming, the will to power, and the contrasts between Apollonian form and Dionysian energy, slave morality and magnanimous master morality. To a considerable extent, he also adopted the Nietzschean “critique of pity,” the masked endurance and transformation of “great suffering” inherent in Nietzsche’s noble morality and tragic vision. “What I have called ‘the Mask’ is an emotional antithesis,” Yeats writes, “to all that comes out of [the] internal nature [of subjective men.] We begin to live when we have conceived life as tragic” (Autobiographies, 189). Yeats’s subordination of “passive acceptance” to “active virtue” in the service of tragic joy was most notoriously displayed in his refusal to include in his Oxford Book of Modern Verse poems “written in the midst of the Great War.” It was idiosyncratic enough to presume to liberate Oscar Wilde’s stronger from his weaker self by cavalierly cutting lines in reprinting “The Ballad of Reading Gaol” in his Oxford anthology; quite another for Yeats to exclude altogether the war poetry of Siegfried Sassoon, Robert Graves, and Wilfred Owen.

Though “officers of exceptional courage and capacity,” and men whose vivid and humorous letters revealed them to be “not without joy,” as poets they felt themselves bound to “plead the suffering of their men,” suffering they made “their own.” Yeats is thinking of Sassoon and Graves, but primarily of Wilfred Owen, who announced from beyond the grave that his book was “not about heroes,” nor “concerned with poetry. My subject is War, and the pity of War. The poetry is in the pity.” As editor, Yeats said, he had “rejected these poems for the same reason that made [Matthew] Arnold withdraw his Empedocles on Etna from circulation; passive suffering is not a theme for poetry. In all the great tragedies, tragedy is a joy to the man who dies.” Repeating, as he often did, Coleridge’s striking image of mimetic passivity, Yeats concluded: “When man has withdrawn into the quicksilver at the back of the mirror no great event becomes luminous in his mind.” In explaining to Dorothy Wellesley why he had omitted the war poets (including Owen, killed in action on November 4, 1918, one week before the Armistice), Yeats repeated his point about “passive suffering” not being a theme for poetry, adding “The creative man must impose himself upon suffering.”{{28}}[[28]]Letters on Poetry from W. B. Yeats to Dorothy Wellesley, intro. Kathleen Raine (London and New York: Oxford University Press, 1964), 21; cf. 124-26. Yeats, Introduction to Oxford Book, section xv. Matthew Arnold had de-canonized Empedocles on Etna because, he said in the Preface to his Poems (London: Longmans, 1853), “no poetical enjoyment can be derived” from situations “in which the suffering finds no vent in action” (viii). Nevertheless, Arnold’s decision was as regrettable as Yeats’s. Owen’s famous description is from a draft-Preface for a collection of poems he hoped to publish in 1919.[[28]]

The contrast between “passive acceptance” and “active virtue” is more palatably symbolized in the opening movement, “Ancestral Houses,” of Yeats’s sequence, Meditations in Time of Civil War. Fusing Coleridge’s mechanical-organic distinction with his own elegiac reverence for the Anglo-Irish aristocratic tradition, Yeats counters the fountain-image of Plotinus with an overflowing fountain of autonomous life associated with Homer and Nietzsche, whose will to power and morality of master rather than of slave is evident in the imagery:

Surely among a rich man’s flowering lawns,

Amid the rustle of his planted hills,

Life overflows without ambitious pains;

And rains down life until the basin spills,

And mounts more dizzy high the more it rains

As though to choose whatever shape it wills

And never stoop to a mechanical

Or servile shape, at others’ beck and call.

Mere dreams, mere dreams! Yet Homer had not sung

Had he not found it certain beyond dreams

That out of life’s own self-delight had sprung

The abounding glittering jet….{{29}}[[29]]The caveat (“Mere dreams, mere dreams!”) is followed by recovery: “Yet Homer had not sung/ Had he not found it [the abounding jet sprung out of “life’s own self-delight”] certain beyond dreams.” But the pattern of vacillation continues in the lines that immediately follow, since “now it seems,” in the twilight of the Anglo-Irish tradition, as if “some marvellous empty sea-shell” (a beautiful fossil that once housed life), and “not a fountain, were the symbol which/ Shadows the inherited glory of the rich.”[[29]]

In A Vision, Yeats distinguishes passively accepted “necessity and fate” from a chosen “destiny,” and antithetical “personality” (creative, active) from primary “character” (imitative, passive): “rhetorical” concepts and contrasts that play out in “A Dialogue of Self and Soul,” where Yeats makes “poetry” out of the “quarrel” with himself. Prior to Self’s triumphant recovery, he wonders how one can escape what Yeats called in “Ancestral Houses” that “servile shape”:

That defiling and disfigured shape

The mirror of malicious eyes

Casts upon his eyes until at last

He thinks that shape must be his shape.

In the end, what Hegel and, later, feminist critics would call the Gaze of the Other, must be countered by the assertion of creative autonomy. As Yeats famously declared, “soul must become its own betrayer, its own deliverer, the mirror turn lamp.”{{30}}[[30]]This celebrated phrase, from the 1936 Introduction to the Oxford Book of Modern Verse, later supplied M. H. Abrams with both title and epigraph for his 1953 landmark study of Romantic theory, The Mirror and the Lamp.[[30]] In “A Dialogue of Self and Soul,” the servile mirror of passive acceptance is replaced by active self-redemption. The internal “quarrel” between Self and Soul issues in that “Unity of Being” Yeats always sought, but, after 1903, not through exclusion but through inclusion, an antinomial vision accepting, not half, but the whole dialectic. In the language of Heraclitus, a Greek philosopher as important to Yeats (who aligned him with Blake and Nietzsche) as to T. S. Eliot, “attunement” can only be achieved through the “counter-thrust” that “brings opposites together,” for “all things come to pass through conflict.”{{31}}[[31]]Charles H. Kahn, The Art and Thought of Heraclitus: An Edition of the Fragments with Translation and Commentary (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1979), Fragment #8 (Diehls-Kranz enumeration). This passage was used by Eliot as the second of two untranslated fragments (the second is “The way up and the way down is one and the same”) as epigraphs to the first printing of “Burnt Norton,” the opening poem of what became Four Quartets. Both were later printed to apply to the sequence as a whole. See Jewell Spears Brooker, “Eliot and Heraclitus,” in New Pilgrimages: Selected Papers from the IAUPE Beijing Conference in 2013, ed. Li Cao and Li Jin (Beijing: Tsinghua University Press, 2015), 259-69. Brooker does not refer to Yeats in her paper, but, as earlier noted, in the ghost-encounter in the final poem of Four Quartets, Yeats and Eliot may be seen as one more example of opposites “united in the strife that divided them.”[[31]] As Soul-supporting George Russell (A.E.), “saint” to Yeats’s “poet” and “swordsman,” surmised in a letter to his friend about the poem, “perhaps when you side with the Self it is only a motion to that fusion of opposites which is the end of wisdom.”{{32}}[[32]]Letters to W. B. Yeats, ed. Richard J. Finneran, George Mills Harper, and William M. Murphy, 2 vols. (London: Macmillan, 1972), 2:560. Yeats wrote Dorothy Wellesley in 1935, “My wife said the other night, ‘AE is the nearest to a Saint you or I will ever meet. You are a better poet but no saint. I suppose one has to choose’” (Letters, 838). Yeats’s poem “The Choice” (1931) begins, “The intellect of man is forced to choose/ Perfection of the life, or of the work.” Finding, as Nietzsche said, “one more stimulus to life” in the “opposition” between “chastity and sensuality,” antithetical Yeats chooses sensuous poetry.[[32]]

Those opposites—reflected in shorthand in the old diagram Yeats drew in the margin of his Nietzsche anthology, and played out in many of the major poems that followed—set the One, Logos, universal Truth, Eternity, and Divinity against the Many, Contraries, minute Particulars, Moments in time, and Humanity. But fusion, ultimate reconciliation at a dialectical higher level, requires that provisional clash of opposites; for (Blake again) “without Contraries is no progression.” The “Dialogue of Self and Soul,” perhaps Yeats’s central poem in terms of its ramifications throughout his work, before and after, is also his greatest exercise in creative, life-affirming masking. In the poem’s final fusion of opposites, or antinomies, or Heraclitean counter-thrusts, Yeats’s crucial precursors are Blake and Nietzsche (as well as Macrobius, whose Commentary on Cicero’s dialogue between ghost and grandson in “The Dream of Scipio” Yeats echoes in order to alter).{{33}}[[33]]For a discussion of the Commentary on Cicero’s Somnium Scipionis by the 4th-century Neoplatonist Macrobius, see Patrick J. Keane, Yeats’s Interactions with Tradition (London and Columbia: University of Missouri Press, 1987), 143-44.[[33]] But a role is also played by Oscar Wilde, as audacious as the Romantic poet and the German philosopher in reminding Yeats that the play of antinomial “contraries” is artistic, and that “the truths of metaphysics are the truths of masks.”

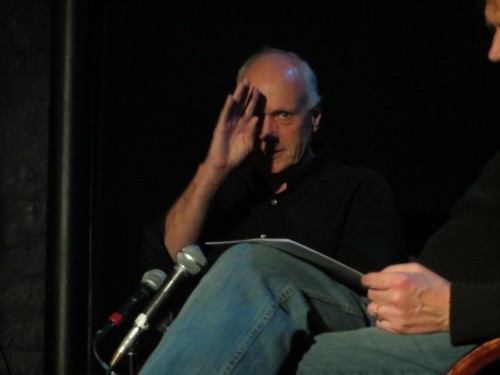

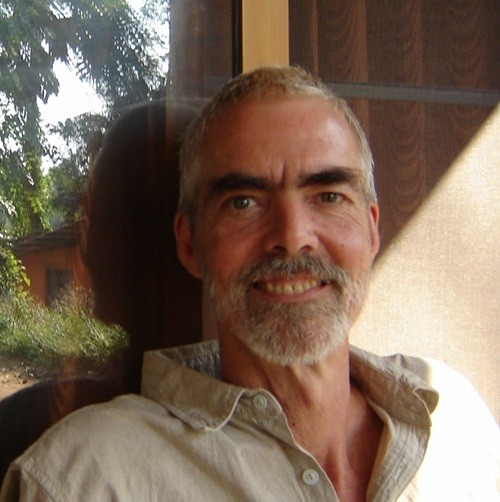

Bronzes cast from Hildo Van Krop’s masks for 1922 Dutch production of Yeats’s The Only Jealousy of Emer.

Bronzes cast from Hildo Van Krop’s masks for 1922 Dutch production of Yeats’s The Only Jealousy of Emer.

(From l. to r.) Emer, Cuchulain, Woman of the Sidhe.

—Patrick J. Keane

x

Numéro Cinq Contributing Editor Patrick J. Keane is Professor Emeritus of Le Moyne College. Though he has written on a wide range of topics, his areas of special interest have been 19th and 20th-century poetry in the Romantic tradition; Irish literature and history; the interactions of literature with philosophic, religious, and political thinking; the impact of Nietzsche on certain 20th century writers; and, most recently, Transatlantic studies, exploring the influence of German Idealist philosophy and British Romanticism on American writers. His books include William Butler Yeats: Contemporary Studies in Literature (1973), A Wild Civility: Interactions in the Poetry and Thought of Robert Graves (1980), Yeats’s Interactions with Tradition (1987), Terrible Beauty: Yeats, Joyce, Ireland and the Myth of the Devouring Female (1988), Coleridge’s Submerged Politics (1994), Emerson, Romanticism, and Intuitive Reason: The Transatlantic “Light of All Our Day” (2003), and Emily Dickinson’s Approving God: Divine Design and the Problem of Suffering (2007).

x

x