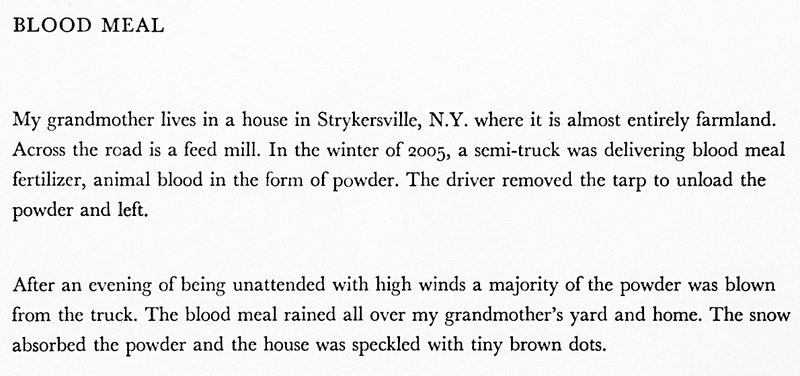

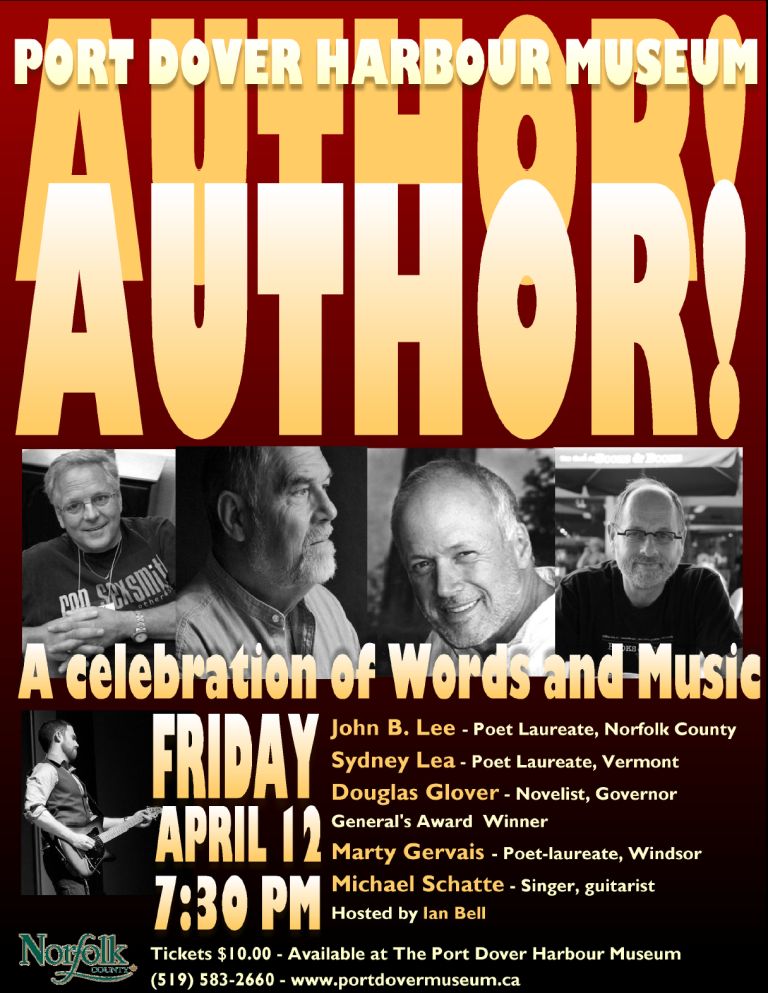

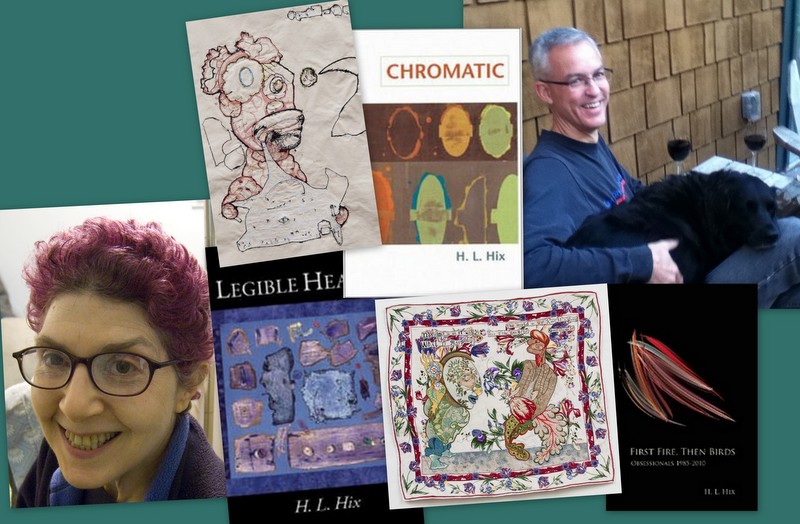

When the artist China Marks, who specializes in amazing drawings she does with a sewing machine, offered to interview the poet H. L. Hix for Numéro Cinq, I had no idea the interview would turn into a conversation, a mutual interview, and that the conversation would metamorphose into this wonderfully intelligent, cross-genre meditation on the foundations and process of art whatever form the art takes. Not only that but the conversation takes as its starting point an essay by the poet Julie Larios published on these pages, so that NC is part of the conversation, that is, as a catalyst and locus where artists and idea come together (across continents, across disciplines, you can hear the cultural tectonic plates colliding in the background). If we were on the Left Bank, NC would be a cafe and China Marks and H. L. Hix would be leaning across a marble-topped table sipping absinthe and talking intensely (and you would be listening, you, dear NC reader, at the next table). This conversation is packed with quotation, quotable lines, self-reflection — but China and Harvey are old friends, too, and that comes through, intense, intelligent conversation between friends. They take, as their starting point, a phrase from Richard Wilbur — confounders of category — which they both read in Julie Larios’s essay on riddles; and this conversation is all about confounding categories, crossing boundaries, connecting things that are not connected except in the minds of the artists, about play and the dramatic tensions inherent in confounded categories. A delight in every exchange — though my favourite is the bit about versos, the backs of works of art, especially the backs of China Marks’s sewn drawings.

dg

China Marks: Numéro Cinq recently published an essay by Julie Larios on the riddle.{{1}}[[1]]”Who Am I? What the Lowly Riddle Reveals,” November, 2012[[1]] It was full of things that made me think of my own work and to a certain extent yours as well; for instance, “to describe something by describing something else.” And “you turn the reader’s gaze to something clear, physical and believable in order to understand something deep, emotional, and invisible.” She quoted Richard Wilbur as calling riddles “the confounders of category.”

I think that we are both confounders of categories.

H. L. Hix: I too enjoyed the Larios essay, especially her way of seeing riddles as “mak[ing] us rethink our assumptions.” I certainly want to be — I try to be — a confounder of categories. Wilbur’s term makes me think of Gilbert Ryle’s philosophical term “category mistake,” which consists in treating something from one category as if it belonged to another category, the way we do when we speak of ideas as things. Ryle uses the concept of a category mistake to identify as one purpose for philosophy “the replacement of category-habits by category-disciplines.” I appreciate Ryle’s aim there, but it seems naïve, in that it takes for granted the neutrality of categories, as if they were things in the world rather than human constructions. (In other words, it seems to me to make a category mistake!)

That’s why I want to be a confounder of categories: because I take it that many category-habits are received, or (to put it less mildly) imposed on us. For instance, the pervasive description of persons as consumers is a category mistake, but it doesn’t happen accidentally because of an indifferent category habit: it’s one that Walmart wants us to make, pressures us to make, and benefits from our making. It leads to such individual stupidities as thinking that my purchasing something will increase my worth as a person, and to such collective stupidities as the belief that growth is the highest economic aim. So I don’t just want to discipline categories, I want to confound them. I want to be engaged — in my art, and in other aspects of my life — in an active, ongoing process of resisting received or imposed categories, and creating new ones.

CM: I don’t think you have to try to confound categories, you do it naturally, the way you range over a vast array of subject matter and verse forms, wear so many hats, hang out with visual artists, remain open to possibilities of all kinds. For myself, I can’t remember a time when one thing didn’t connect willy-nilly with something else entirely different and then branch off in several directions. As no one else seemed to notice, I never said anything about what I saw/sensed. By now I am used to it, no, more than that; I understand that categorizations are constructs and if not perceived as such, are impediments to speculative play.

HH: Many people regard play of any sort as a form of irresponsibility: children are permitted to play, the view goes, but adults should not be. But what you’ve just said points up the flaw (or one of the flaws!) in that conception. Thinking of play as irresponsible neglects the fact that coherence depends on association. If I can’t connect one thing with another — and that includes connecting apparently dissimilar things with one another — then I can’t test my view in one area against my view in another. I can’t preclude self-contradiction. In other words, if I don’t get to play, to speculate, then I can’t be responsible. To me, that is one of the ways in which poetry and visual art have both private and civic value: they facilitate the associations that enhance coherence and diminish self-contradiction. They are forms of imaginative caprice that constrain logical and empirical caprice.

But “playful” isn’t the only term I would use to describe your work; I would describe it also as “dramatic,” meaning that it seems to me to depict situations of tension and conflict, just as a stage play or film or novel would. Is there a connection between the importance you place on process in making your work, and the centrality of drama in the work that results?

CM: I do think that what I make is inherently dramatic. I’ve even called my drawings “little dramas.” I consider my role as an artist that of an entertainer. I want my drawings to compel and amuse, to make eyes widen and jaws drop. During the process of making a drawing, I am in the audience as well as on stage, often surprised, sometimes thrilled at what I see, or so bored and restless or unhappy that I make drastic changes, until my own jaw drops….

HH: We started by noting similarities in our work, but maybe this is one difference. I’m inclined to think of my work in contrast to entertainment, after the manner of George Oppen’s journal note that “entertainment ameliorates human life; art means to make human life possible.”

CM: Definitions of art and its functions are just definitions. People will always write about art and decide what it really is or should be. In the meantime, I make art that among other things, entertains. So what?

HH: Point taken. It’s true that defining art is not your project, or mine, nor was it Oppen’s. But I doubt that either of us makes our art without some working conception of art, even if our practice tests or resists that conception as much as it enacts it. We’re not defining words right now, but we couldn’t be using them without an operative conception of their meanings. I think we’re agreed that definition is a distraction, though, in this context, one that leads away from, rather than into, the shared intensity — the confounding of categories — that motivates this conversation. So let me try to reframe things in a way that I think does look toward, rather than away from, that shared intensity.

I’ve known you for give or take fifteen years now, long enough to have seen transitions from sculpture to painting and from paintings to sewn drawings; and long enough to have seen your sewn drawings expand to include books. I’m reminded of Louise Glück’s assertion that “An aspect of relentless intelligence is that it finds no resting place.” How does it happen, or why is it important to you, that your work finds no resting place? What makes your intelligence so relentless?

CM: My art has changed even more in the forty years or so since I graduated from art school. I don’t feel responsible for the changes. I just showed up in my studio every day possible and worked as hard as I could. Did my art morph and change because I had a relentless intellect? I think that I simply gave myself over to process very early in my life as an artist and went where it took me. Process is more than making a single sculpture or drawing. The process of becoming an artist takes most of a lifetime and has affected not just my studio practices but also where I live, what I eat and how I exercise, what I read, who my friends are, the music I listen to, my marital status, even the way I look.

I started out as a sculptor, but always drew for its own sake as well. A series of works on paper begun in 1992 took on a life of its own and since then, except for two installations in the 90’s, the last to describe a world parallel to our own, accessible only through my art, I have mostly drawn; except of course in the mid-90’s, when my drawings grew so big that I moved onto canvas for two years, which led to my being hired to teach painting at the Kansas City Art Institute, where I met you…

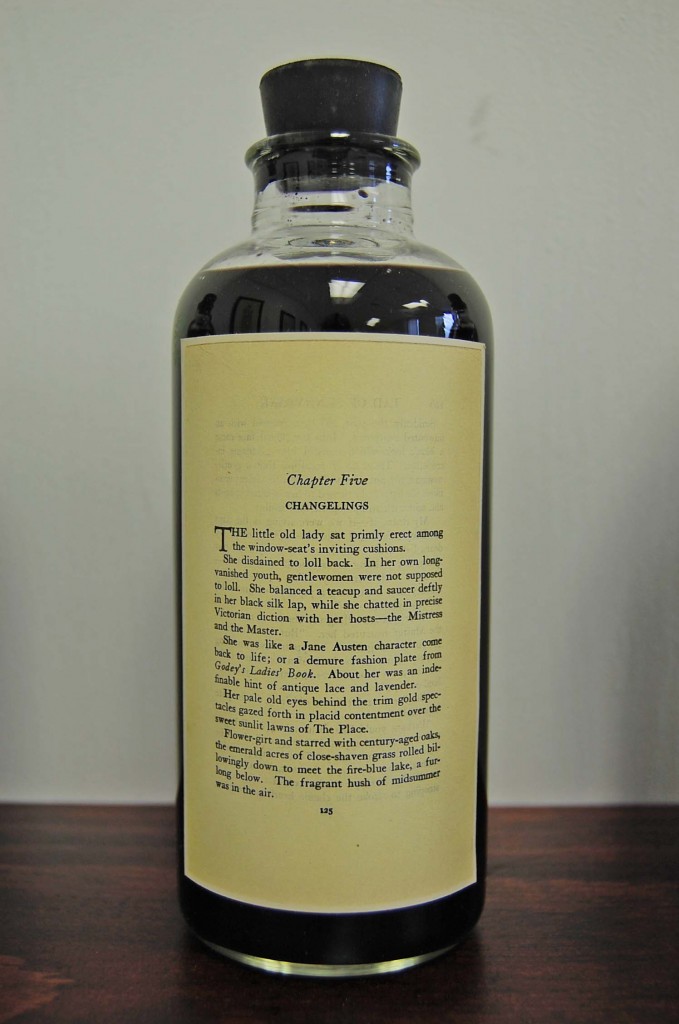

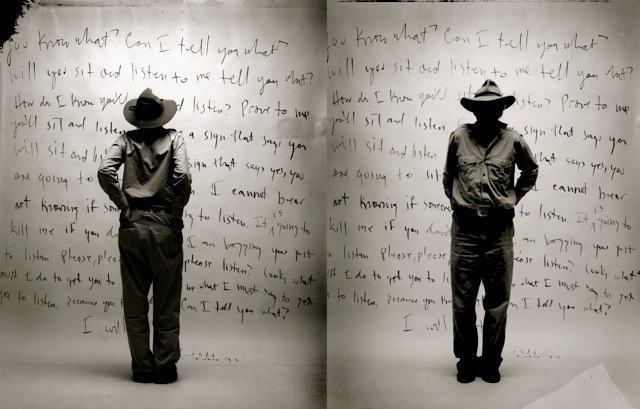

On Dec. 6, 2000, my drawings told me that they had to be sewn, and not by hand: I would have to buy a sewing machine and learn to generate and control a sewn line. It might as well have been the voice of God. I did as I was told, and it turned out to be the most demanding and compelling thing that I have ever done. I knew that I would be making sewn drawings for the rest of my life, and because their potential was infinite, however much time I had, it wouldn’t be enough.

In 2007, Esther Smith, a book artist who loved my sewn drawings, persuaded me to make a little sewn book, which was such a revelation that I resolved to make at least one book a year for the rest of my life. In the spring of 2009, walking my dog after a rainstorm, I found a big black broken umbrella printed with words, and without having any idea of what I would do with it, carried it home. This somehow led to my making my first two text-based books later in the year. I am still making books, but since the fall of 2010, my drawings have also been full of words, and that has changed everything.

People who’ve known my work over many years say that it all looks like my art; the hybrid forms, the seductive line, the visual wit, my interest in patterns, my appropriation of found objects and images, the narrative drive, the idiosyncracy and flamboyance. But that isn’t anything I have to try to do, that’s just what I’m like.

HH: Your remarks that “I just showed up in my studio every day possible and worked as hard as I could” and “that’s just what I’m like” remind me of an answer Rauschenberg once gave in an interview, when he was asked whether he planned his pieces. He said, “No, I have discipline. I work every day and I never know what I’m doing….” The end of his answer was like the end of yours: “you’re just doing something. You’re doing what no one can stop you from doing.”

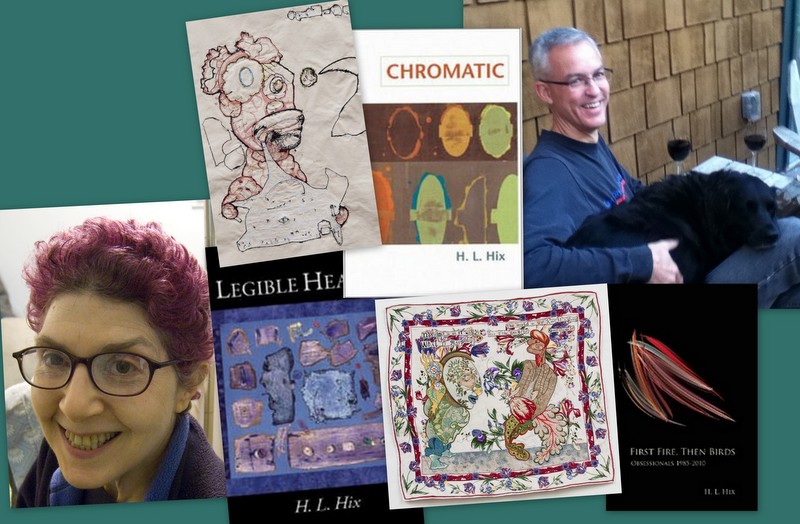

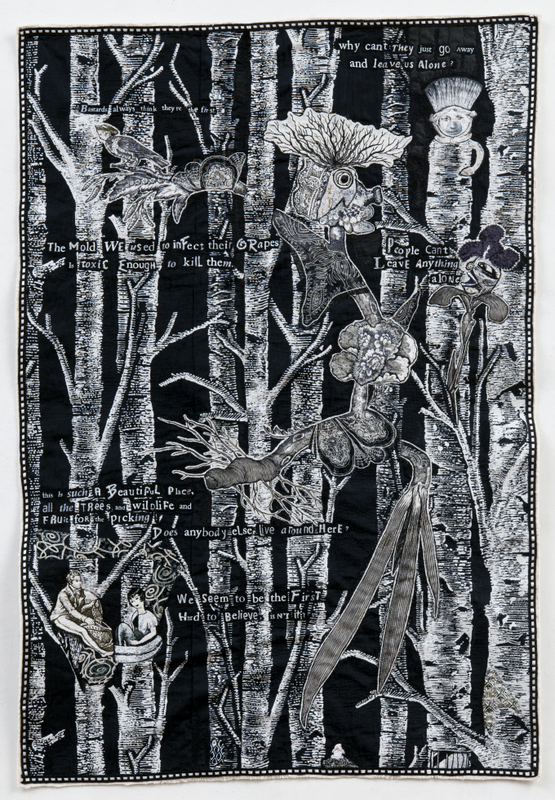

When I look at any of your pieces — I have “Lovely, Dark, and Deep” called up on my computer screen right now — I get the feeling (and would get this feeling even if I weren’t in the middle of conversing with you like this) that you are doing what no one can stop you from doing, or, in the words you just used a moment ago, that your drawings told you what to do, and you did as you were told.

Lovely, Dark, and Deep, 2011

Lovely, Dark, and Deep, 2011

CM: All I ever know is what to do next, even if I have to un-do it the next day or a month later. But I have to do it.

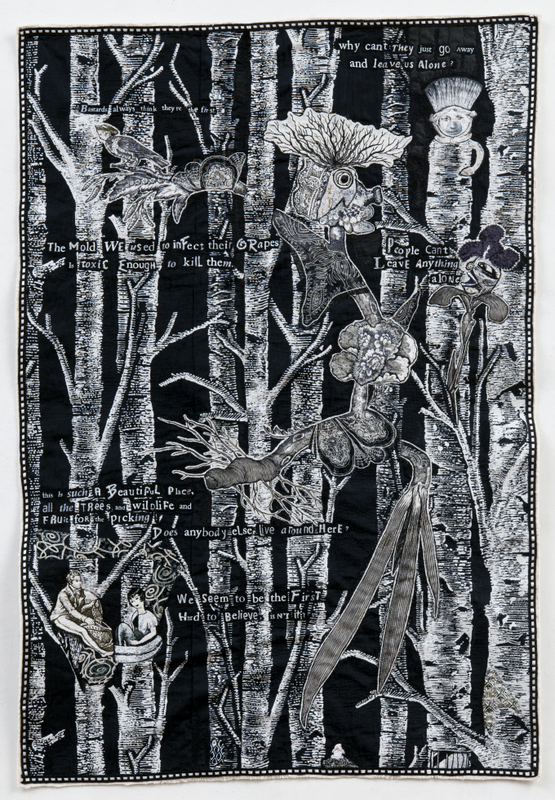

HH: That sense of necessity in the process — just doing what you have to do — raises for me a question about necessity in the result. I have seen the backs of some of your sewn drawings. Each verso has its own integrity and beauty, a complement to that of the recto. Which makes me think of the pedimental sculptures from the Parthenon, painstakingly finished on the back, even though they were made to be positioned in such a way that the back would never be visible. Accident? Design? Is this result (the beauty of your versos) a necessity?

CM: The difference between my versos and the parts of ancient sculptures that were finished even though those parts would never be seen, is that my versos thrive in the dark, neglected and unheeded until they’re photographed at the end. I don’t make them. They happen because sewing machines stitch on the back as well as the front. They are entirely uncalculated, all their power and coherence transmitted from what is occuring on the other side. Mirror-image twins.

HH: You speak of your work with a kind of animism that out of context I might regard skeptically, but that in regard to art I am inclined to embrace, namely that those versos “thrive,” that they are able to “transmit” their power and coherence without being seen. But what I am most fascinated by in your response is the observation that the versos are “entirely uncalculated,” rather than your making them happen. Their power and coherence result directly from your process, but either indirectly or not at all from your intention.

CM: Yes, the power and coherence of my versos result directly from my process, which contains the time it takes to make a particular drawing, my intentions, the workings of my sewing machines, my threads and fabrics, my tools, artifical and natural light, my doing and undoing stitches, the weather, the music I listen to, whether I swam in the morning, what I ate and read that day and the last, etc. etc. The process is much wiser and goofier than I am. By the time I finish a drawing, it is breathing on its own and full of all kinds of things I could never have imagined, including its verso. I make my drawings and books in order to see them. I couldn’t possibly think them up.

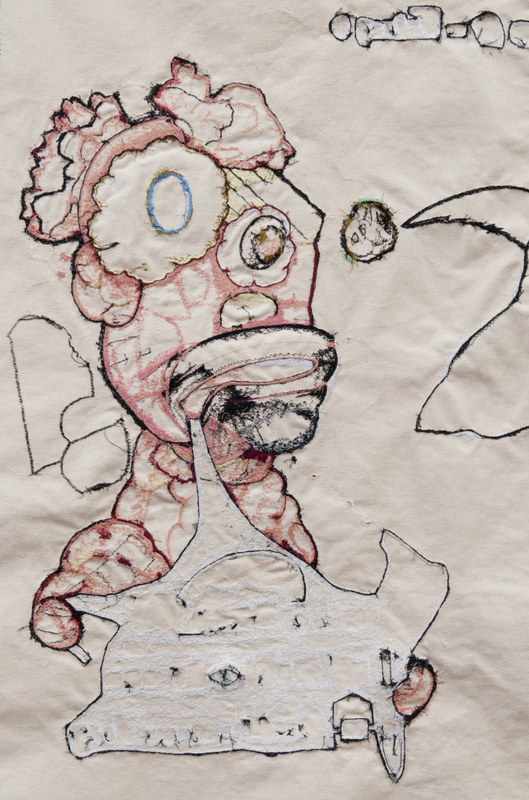

Detail, verso, Bear’s Dream, 2011

Detail, verso, Bear’s Dream, 2011

HH: I wish we were geographically close enough that I could have you in every semester to speak with my writing students. What you’ve just said in relation to your visual art studio practice applies also to a writing practice. But it seems to be, for many people, a very difficult step to take. I mean your conceiving, and maintaining in your creative process, a distinction between making and intention. I find that many aspiring poets believe that making must fulfill an intention that is already complete prior to its enactment, but that assumes that one is oneself the locus of wisdom, and the source of wisdom, in the enterprise.

To think up something first, and then employ the medium as a means to make the already-thought-up thing could make sense only if the smarts are in the person rather than in the medium. But I hear you observing something with which I concur: more wisdom is to be found in one’s medium and in one’s process than in oneself. That shift is radical, and, I believe, all-too-rarely made: from thinking that through one’s art or writing one shows the world to others, to thinking that one’s art or writing might show the world to oneself. When we talk about the importance of process, I take that as at least one thing we mean.

CM: One thought casting back to the beginning of our conversation and a question for you, but they’re related, so I’ll start with the thought. You’ve said that you don’t believe in inspiration. I didn’t look this up, but doesn’t that come from Inspiritus, being possessed of the gods in the form of a divine wind or breath? If we become instruments of our process, about which so much remains stubbornly ineffable, is that much different? There were various ritual practices to summon the gods, standing inside a circle drawn in the dirt at the new moon, bathing and putting on new clothing, fasting, and so forth. Most visual artists and writers need particular conditions in order to work. Only in daylight, only at night, five no. 2 pencils sharpened to a point, a particular word processing program, coffee or scotch, after a run, with a favored brush, whatever it takes to make us ready to give ourselves over to the process.

I think that I have it easier than you, because I start by selecting a hundred or more scraps of patterned fabric, backed with fusible adhesive, from thousands so prepared, and go from there. But how do you start? With an idea or a phrase? Do you write in your head for a while before you let yourself write it down? Is it always the same way? That’s my question. Where do your poems come from? And how?

HH: It may be that some of the affinity I perceive between your drawings and my poems derives from affinity between your process and mine. I do have rituals — I write early in the morning, I wear as a talisman a ring given me by the poet William Meredith, I write with an elegant fountain pen Kate gave me — but the content of the rituals is (as your comment suggests) not as important as the fact of the rituals. I don’t think one need believe in the real existence of something invoked (such as gods or divine winds), to find efficacy in the act of invoking. In fact it may be better if one does not so believe, as Simone Weil implies when she calls it “a method of purification” to pray, “not only in secret as far as men are concerned, but with the thought that God does not exist.”

But it’s the collecting I’m focused on here as an element of process we share. You say you start with scraps of patterned fabric you’ve prepared. I start with scraps, too, only in my case it’s scraps of language. For me, the writing of a poem is not an act of self-expression but an act of listening. A poem, for me, is not the externalizing of an idea or feeling that was inside me prior to the poem, but the derivation of a linguistic construct implicit in a fragment of language, as one derives a theorem from premises in mathematics. It’s not that I show others in my poems what I happen to feel or think, but that my poems show me what I ought to feel or think. As with a mathematical theorem, it is their necessity, not their accidental connection to me, that matters.

CM: Could you talk a little about how that necessity operates in your poem “What Creature In What Darkness”?

What Creature In What Darkness

So accustomed to light have we grown (evolved, really,

it’s not you and me only, not decision exactly)

that we forget the lives, species, entire biotas

underground, in caves or tunnels no light tastes, ever.

Which doesn’t mean they don’t inhabit us, or that we

share with them no (actual, not merely potential) traits.

In water the whale, in air the hummingbird:

to these totems I arch elements of identity.

Underground, who knows what sister life-form waits.

I have my library of unconscious states

that I claim awareness of, and accept,

though clearly that’s contradiction and self-deception.

What creature inhabiting what damp darkness

will show me what I might morph into, might have been

all this time? Does it glow? What best describes its limbs?

What sounds in what notation by what lurching has it scrawled?

Does it have limbs? Does it crawl? Or is it sessile,

gasping then lisping what vagrant spores and molds it may?

Or just patient, able to trace but waiting instead, curled?

This is my preferred world, the shadow world

that does not — need not — speak, will not be spoken to.

All this flailing at communication — I’m flailing now —

just shows I haven’t learned, may never learn, to abide.

Who realizes the desperate still wants the needful.

Wait, the subterranean advises. Wait, wait.

Because only by waiting may one hear the gritty

shifting of Patience itself. Even that’s misleading, though:

the one who waits despises Because.

When she who is here with me is here with me, with me

beneath this city there is another city,

ruins not restored, not even preserved, but hosting

a less demonstrative but equally insistent

other estimation. When she is here with me,

she is the other city, host to (or sum of)

secret othernesses and nethernesses.

We need not think of lives as woven by a loom

to think of them as interwoven, and need not pretend

they watch us, or care, to make of them second chances,

alternatives, opportunities to assume

other orientations to the textured vacuum.

HH: In an important sense, you are the source of this poem. Maybe you’ll remember a studio visit Kate and I made a couple of years ago to see what you were working on. During that visit you gave me an exhibition catalog of work by a painter friend of yours, Thomas Lyon Mills. His work stayed in my head, so when I began the “Show and Tell” project on my blog — the project in which poets respond to images by artists, and in which your own work appears — I looked him up and asked him to participate. This poem derives from his participation.

“What Creature In What Darkness” is one of a sequence of poems, all of which come from that “Show and Tell” project. Each poem in the sequence takes the form of a “glosa,” so in fulfillment of that received form the last line of each stanza is quoted: the last lines of the first two stanzas come from the artist statement of the particular artist in question, and the last lines of the last two stanzas come from the poem the poet made in response to the artist’s work.

“What Creature In What Darkness” derives from the pairing of the artist Thomas Lyon Mills with the poet Evie Shockley. So the lines “I have my library of unconscious states” and “This is my preferred world, the shadow world” both are quoted directly from Mills’s artist statement, in which he describes his (amazing) process, which centers on research in underground catacombs in Rome. The lines “beneath this city there is another city” and “other orientations to the textured vacuum” come from the poem Shockley wrote in response to Mills’s work. “What Creature In What Darkness” tries then to listen to what words and images follow inevitably from their words and images.

To put this another way, those lines borrowed from Thomas Lyon Mills and Evie Shockley perform the role your selected scraps of patterned fabric play.

CM: Haven’t you sometimes also used borrowed language more directly as found objects, as in Chromatic, where you appropriated early 20th century vernacular speech to great effect?

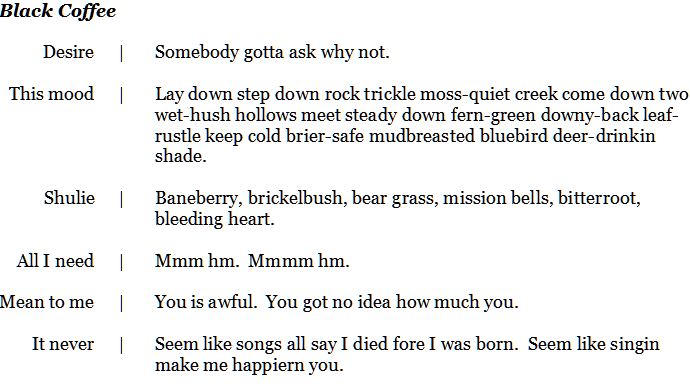

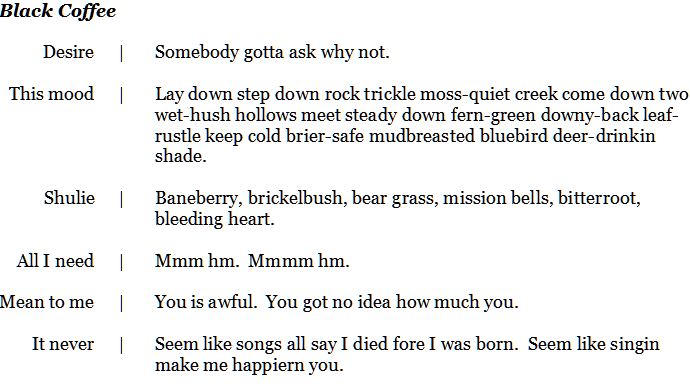

HH: Appropriated language definitely is important in Chromatic. Almost all my poetry starts with found language. Introspection and perceptual observation follow, but the found language almost invariably offers the starting point. That found language might be “intellectual,” derived from things I read: that happens, for instance, in the first sequence in Chromatic, “Remarks on Color,” which draws on two sources, Wittgenstein’s Remarks on Colour and Mondrian’s Natural Reality and Abstract Reality. But the found language might also come from other sources, and you’re right about my interest in vernacular speech. I assume you’re referring to “Eighteen Maniacs,” the second sequence in Chromatic. Here’s one of the shorter of those poems.

One reviewer mistakenly identified these poems as operating in “blackface,” trying to mimic African-American dialect. But I’m after a much broader attention to dialect and vernacular. So the sequence does include usages drawn from (or based on) African-American vernaculars, especially the rich language that grew up around jazz. (The sequence itself is a kind of abbreviated history of jazz, as signalled by the title: “eighteen maniacs” was one way Duke Ellington referred to his band. Each piece in the sequence revolves around one jazz musician. In “Black Coffee,” all the words in the left-hand column come from Sarah Vaughan: titles of her songs, etc.) But “Eighteen Maniacs” includes other vernaculars as well, such as the regional dialects I heard growing up in small towns in the South. The “seem like” in the last sentences here is not peculiar to African-American vernacular, but shows up in many regional and ethnic dialects, often enough that in linguistics it has a name, “sibilant deletion.”

CM: Was it always words for you, even as a boy? I ask because I remember a crucial time in my own life, when I was about 19, when I gave up on words and embraced image-making.

HH: Even though I was a late-comer to poetry per se, and even though I wouldn’t have known it at the time, it was always words for me. I drew a lot as a boy, birds in grade school when I was obsessed with birds, cars in high school when I was obsessed with cars. But even though I grew up in a household (and in school districts) that didn’t introduce me to poetry, I can see in looking back how the household’s preoccupation with language nurtured my own. My father, a journalist, made his living with words; there was always popular music playing, so the lyrics of songs performed by Johnny Cash (my Father’s favorite) and Andy Williams (my Mother’s) and the Carpenters (my older sister’s) and Olivia Newton-John (my younger sister’s) were in my head; it was a religious household, so I listened to a thousand alliterative Baptist sermons and memorized a boatload of Bible verses in Sunday School; and so on.

Consequently, when at last I was exposed to poetry, as a college undergraduate, I was “primed” for it by all that intense attention to other language uses. I’d been socialized, without being aware of it in these terms, into the sense that language mattered, indeed (this especially from the religious context, in which language, in the form of prayer, is the vehicle through which one speaks to God, and also, in the form of scripture, the vehicle through which God speaks) that language is a matter of life and death.

It’s interesting to me, in the context of this question, though, that words have become quite active and prominent in your recent drawings. Which in one way may not be so surprising: I would want to modify the self-description you give in asking this question. Yes, you gave up on words in the sense that you went for a long time not producing words as part of your work, but it seems to me that — at least for as long as I have known you — you have been very actively receiving words as one aspect of the preparation for your work. Your omnivorous (and category-confounding) attention, your relentless intelligence, includes intense attention to words.

CM: I was a great, omnivorous reader as a child and adolescent, and I’ve written all my life, long letters back in the days when people wrote letters, accounts of dreams, descriptions of acute psychological states, journals, richly detailed assessments of arts-in-the-schools for my job at the NYC Board of Education, stories and poems, especially when I was in love. I also talked a blue streak. My late friend Stanley Landsman once predicted that if after we died, all the words we’d spoken were heaped in a pile in front of us, my pile would be twice as big anybody else’s.

But my facility with words is what made me distrust them. They could mean almost anything, while during my adolescence and early adulthood, most of what mattered was worldess and sensory, sexual, instinctive, uncanny. In those days, I used words to “pass” as not-crazy, till I couldn’t any more.

But when I started making text-based books in 2009 after a chance encounter with a dead umbrella printed with words, it was just part of my process. And it turned out that I had a lot to say, more than I can fit in my drawings. So I’ve begun to collaborate with letterpress printers. The first project, a little poem of mine, four verses with six lines in each, printed as a pamplet, is already in the works. A broadside comes next, and I already have the text for it.

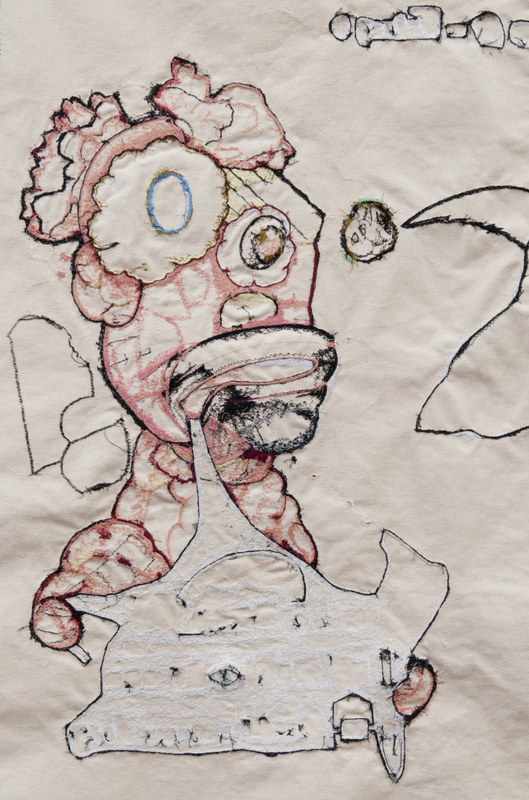

HH: It seems like we’re making a connection here between process and paying attention. We’ve talked about the importance process has for us, about its centrality to our practice, but how does that play out in a particular work, such as “The Language of Flowers”? How does process amount to paying attention?

The Language of Flowers, 2012

The Language of Flowers, 2012

CM: One must be fully present to make process-directed work, expanding one’s attention to take in the work at hand, but also to a lot of other things that might be relevant to the process…

When I visited Gerry Trilling in Kansas City in 2010, I bought two vintage scarves at an “antiques” mart in the river bottoms. I really wanted them and I could afford to buy them, but I had no idea of what to do with them. I rarely do. Almost two years had passed before it occurred to me to try to create a space inside the borders of the Liz Claiborne scarf and then to construct two eccentric, flamboyant figures to occupy that space. I don’t remember deciding that one figure should be static and the other dynamic. I concentrated on keeping as much of the original print as possible and altering as little as possible what I imported. As these fellows came to life, it occurred to me that it must be so strange for them: they’d changed from scraps of printed fabrics to beings — nothing was as it was! Which is how the text began.

But as I refined the drawing, they seemed more and more like Renaissance courtiers in a walled garden, which is how the text ended. It’s probably just as applicable to our time. It’s pleasant enough, but the world as we know it is gone. Guard yourself.

HH: That’s it, though. This image has in spades one of the forms of dramatic tension I experience — see and feel — in all your work. One the one hand, it emphasizes features that make it entertaining: a bright palette, playful figuration, dynamic composition, a “busy” surface, and so on. But on the other hand, this entertaining, even delightful, image is terrifying. This drawing, like your other drawings, is the world: I as a viewer recognize the figures as figures, etc. But it’s not the world given to us by Hollywood romantic comedies or tv sitcoms. The world as we know it is gone, replaced by the world of the drawing.

CM: I don’t think that anything I make really stands outside our world, or rather, the various overlapping and interpenetrating worlds that comprise out present reality. Things out there, murders, starvation, genocide, the coarsening and brutalization of whole populations, natural disasters and extinctions, are terrifying, not The Language of Flowers.

HH: And yet you spoke earlier of a world parallel to our own, accessible only through your work. That seems an important complement to what we’re discussing here. That tension/paradox is one way I would try to speak of the importance your work has for me. I contend that one can’t know this world by knowing only this world. (The facts, in other words, are not enough.) To take the most obvious kind of example, our capacity for ethical judgments depends on our imagining other worlds. To say that women and members of ethnic minorities ought to have the same rights as males of the privileged ethnic group is to imagine a world parallel to our own, and the “ought to” imputes to the imagined parallel world a “reality,” a force, greater than that of the “real world,” the world as we know it.

So I’d repeat your words, “The world as we know it is gone. Guard yourself.” And add: gird yourself.

CM: And yet somehow, every glance into the abyss sends us back to our work with fresh vigor, I to my drawings, you to your poems. Don’t you have a poem or part of a poem about that? It would make a nice end to this.

HH: Maybe they’re all about that, but here’s one I’ll re-title for this context.

Another Glance Into the Abyss

But that my having fallen came first,

I had not known to call falling

this feeling of following grainy shades

into gray, waving for want of wings,

or fog this silent summoning,

a city sunk whole under a sea.

Who would watch waves must lean into wind.

They wind up lean who long want rain.

If not for waiting, why have we mouths?

If not for failing to fly, why fingers?

— China Marks & H. L. Hix

————————

H. L. Hix lives in the mountain west, where he marvels at how late in the summer it is before hummingbirds arrive at 7,200 feet, at how hardy pocket gophers are, and at the fact that he can survive at an altitude at which cockroaches cannot. He and his partner, the poet Kate Northrop, live in an 1880s railroad house, and their studio space is converted from what was once a barn. His recent books include a “selected poems,” First Fire, Then Birds: Obsessionals 1985-2010 (Etruscan Press, 2010); a translation, made with the author, of Eugenijus Ališanka’s from unwritten histories (Host Publications, 2011); an essay collection, Lines of Inquiry (Etruscan Press, 2011); and an anthology, Made Priceless (Serving House Books, 2012). His website is www.hlhix.com.

China Marks was born and educated in Kansas City, MO, earning a BFA in Sculpture from the Kansas City Art Institute. A Fulbright-Hayes fellowship took her Katmandu, Nepal, where she spent sixteen months constructing a major installation out of local materials. On her return to the United States, she was awarded a graduate fellowship by the Danforth Foundation. In 1976, having received an MFA in Sculpture from Washington University in St. Louis, China moved east to make art. She has received numerous grants and awards, including three fellowships from the New Jersey State Council on the Arts, a Mid-Atlantic Arts fellowship, two George Sugarman Foundation grants, and two New York Foundation for the Arts fellowships, most recently in 2011, when she was also named a Gregory Millard Fellow. Since 1999 China Marks has lived and worked in Long Island City, a block and a half from the East River. Her work is shown in galleries and museums in the United States and Europe. She is represented by the J. Cacciola Gallery in New York. Her drawings will be shown there in May as part of a group show.

—————

Marilyn R. Rosenberg & Nance Van Winckel

Marilyn R. Rosenberg & Nance Van Winckel READ, closed 5 1/8”h x 4 1/8”w, color photo copy edition of 15 with collage, visual poetry artists book with hand made pop up.

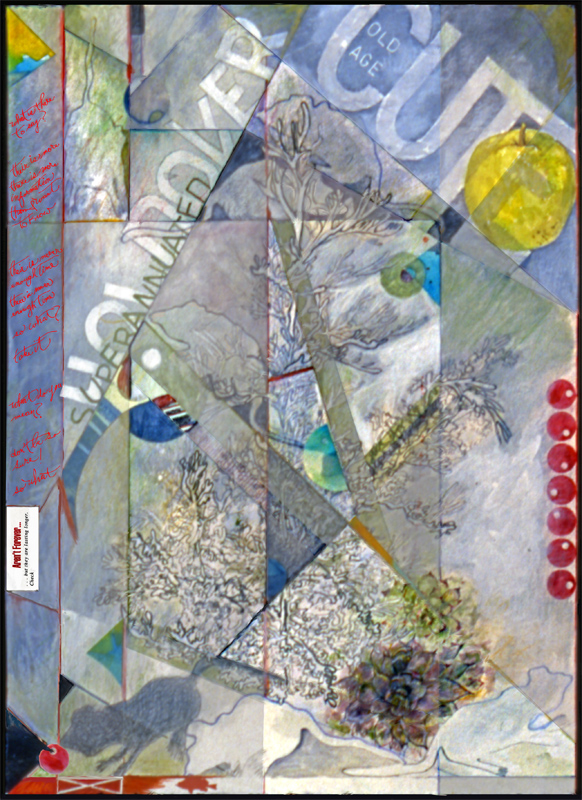

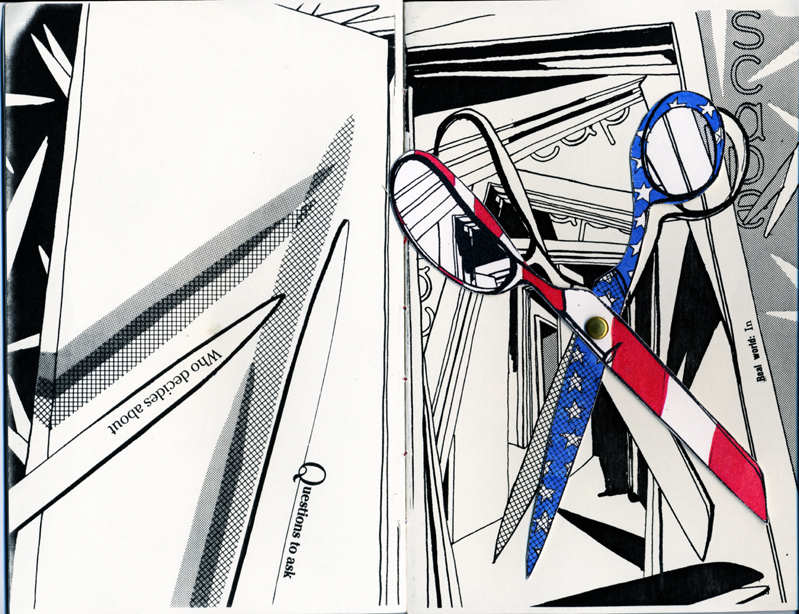

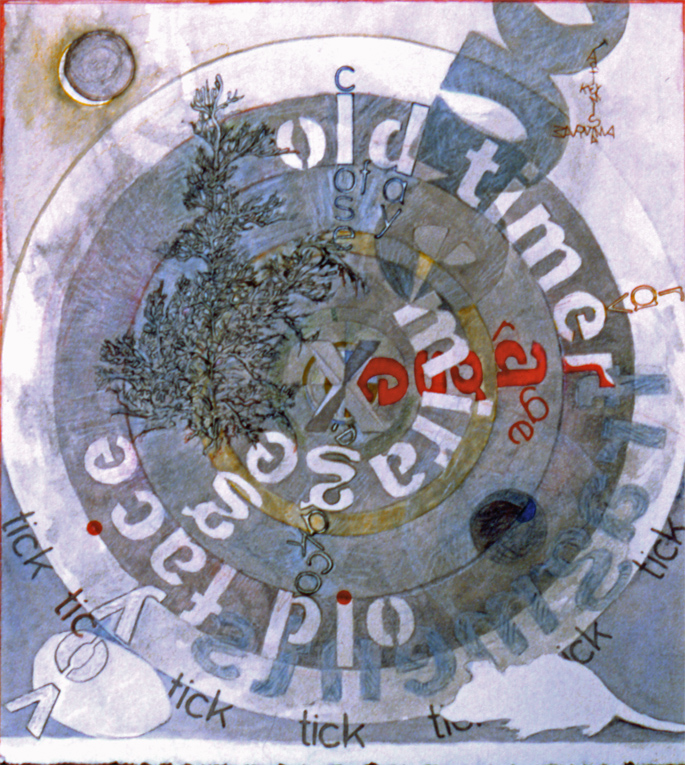

READ, closed 5 1/8”h x 4 1/8”w, color photo copy edition of 15 with collage, visual poetry artists book with hand made pop up. VERBIAGE, 22 1/2 h x 16 1/2” w, visual poetry/drawing.

VERBIAGE, 22 1/2 h x 16 1/2” w, visual poetry/drawing. DRIFT AGAIN, size variable, visual poetry/drawing/virtual collage

DRIFT AGAIN, size variable, visual poetry/drawing/virtual collage LISTEN-HEAR, about 12.50″h x 32 “w, visual poem/drawing, facing pages

LISTEN-HEAR, about 12.50″h x 32 “w, visual poem/drawing, facing pages REST, was 37″h x 48″w*, visual poem/drawing, facing page.

REST, was 37″h x 48″w*, visual poem/drawing, facing page. OR WORK, was 37″h x 48″w, visual poem/drawing, facing page.

OR WORK, was 37″h x 48″w, visual poem/drawing, facing page. Excerpt detail from page 16 from the edition etceteras

Excerpt detail from page 16 from the edition etceteras  OPEN HOUSE, closed 8 1/2” h x 5 1/2”w, especially pages 10-11 with the scissors collage, photo copy edition visual poetry artists’ book with movable collage. Edition 100, printed with five different photo printers.

OPEN HOUSE, closed 8 1/2” h x 5 1/2”w, especially pages 10-11 with the scissors collage, photo copy edition visual poetry artists’ book with movable collage. Edition 100, printed with five different photo printers. DOCKAGE, 16 “h x 14 3/4” w, visual poetry/drawing; master for a few prints of various sizes, image altered for stamp sheet edition

DOCKAGE, 16 “h x 14 3/4” w, visual poetry/drawing; master for a few prints of various sizes, image altered for stamp sheet edition

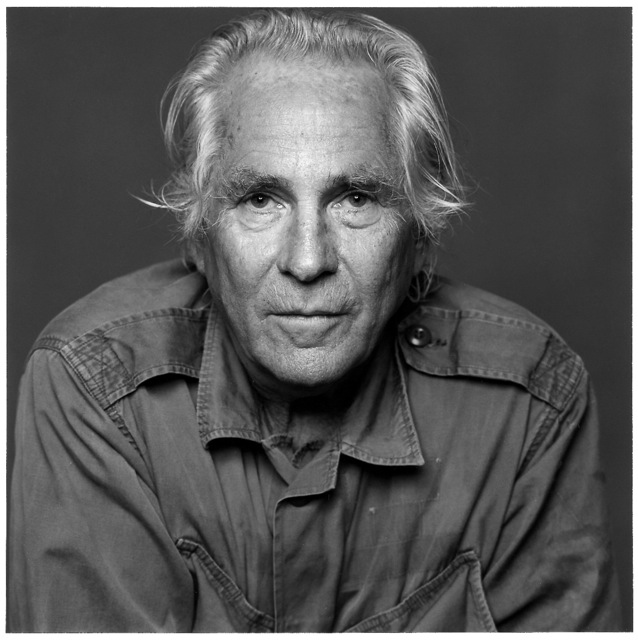

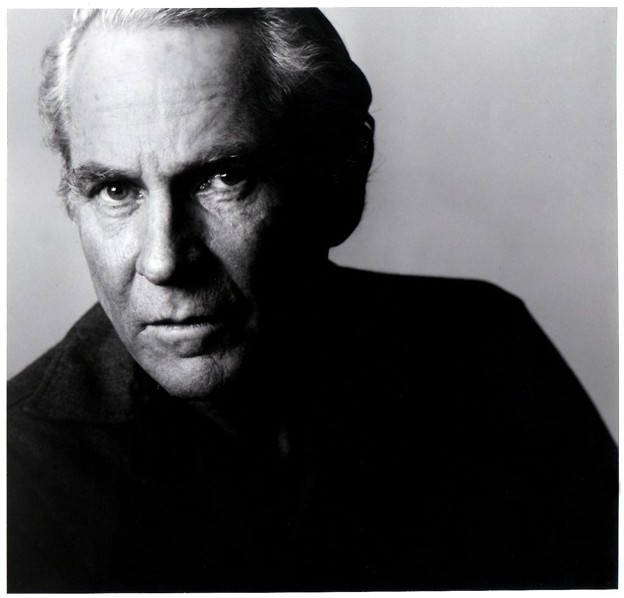

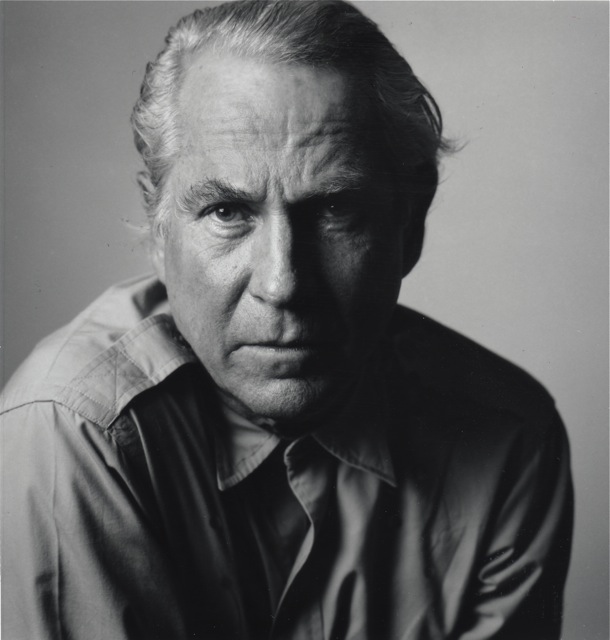

Douglas Glover, photo by Danielle Schaub

Douglas Glover, photo by Danielle Schaub Sydney Lea

Sydney Lea John B. Lee

John B. Lee Marty Gervais

Marty Gervais Michael Schatte

Michael Schatte

Lovely, Dark, and Deep, 2011

Lovely, Dark, and Deep, 2011 Detail, verso, Bear’s Dream, 2011

Detail, verso, Bear’s Dream, 2011

The Language of Flowers, 2012

The Language of Flowers, 2012