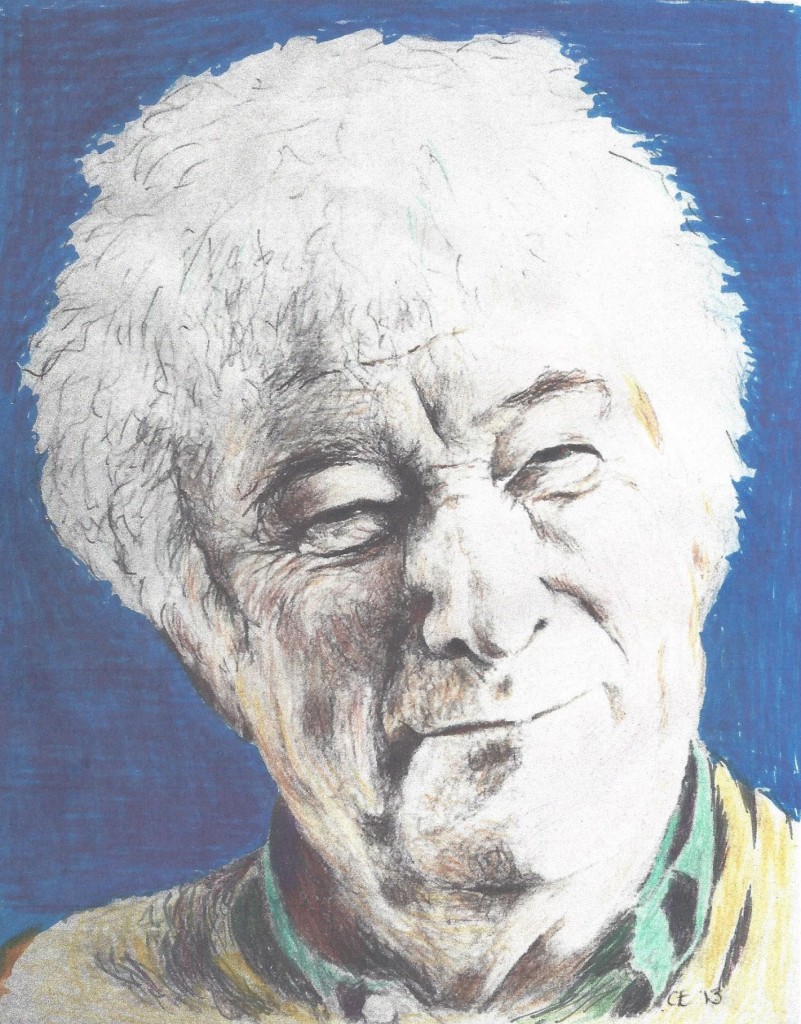

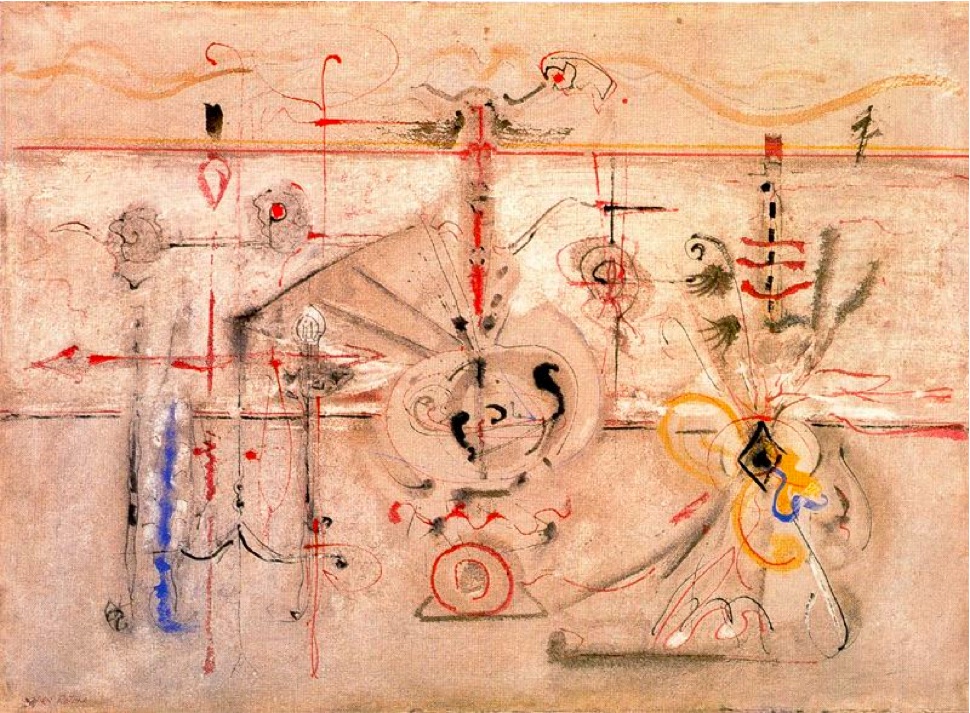

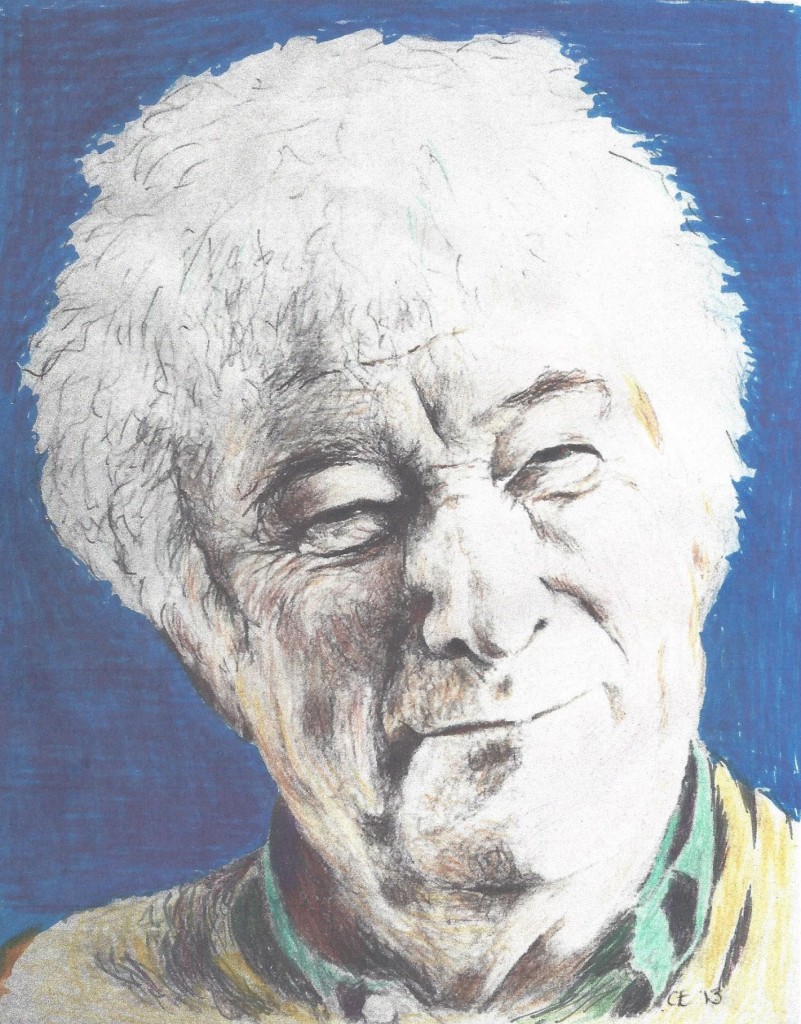

Catherine Edmunds’ 2013 sketch of Seamus Heaney painted by Patrick J. Keane

Catherine Edmunds’ 2013 sketch of Seamus Heaney painted by Patrick J. Keane

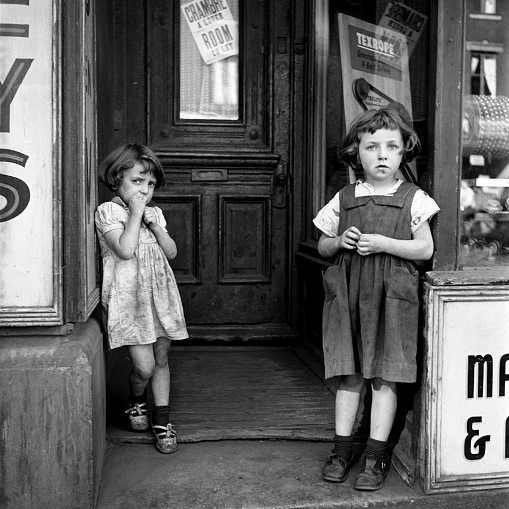

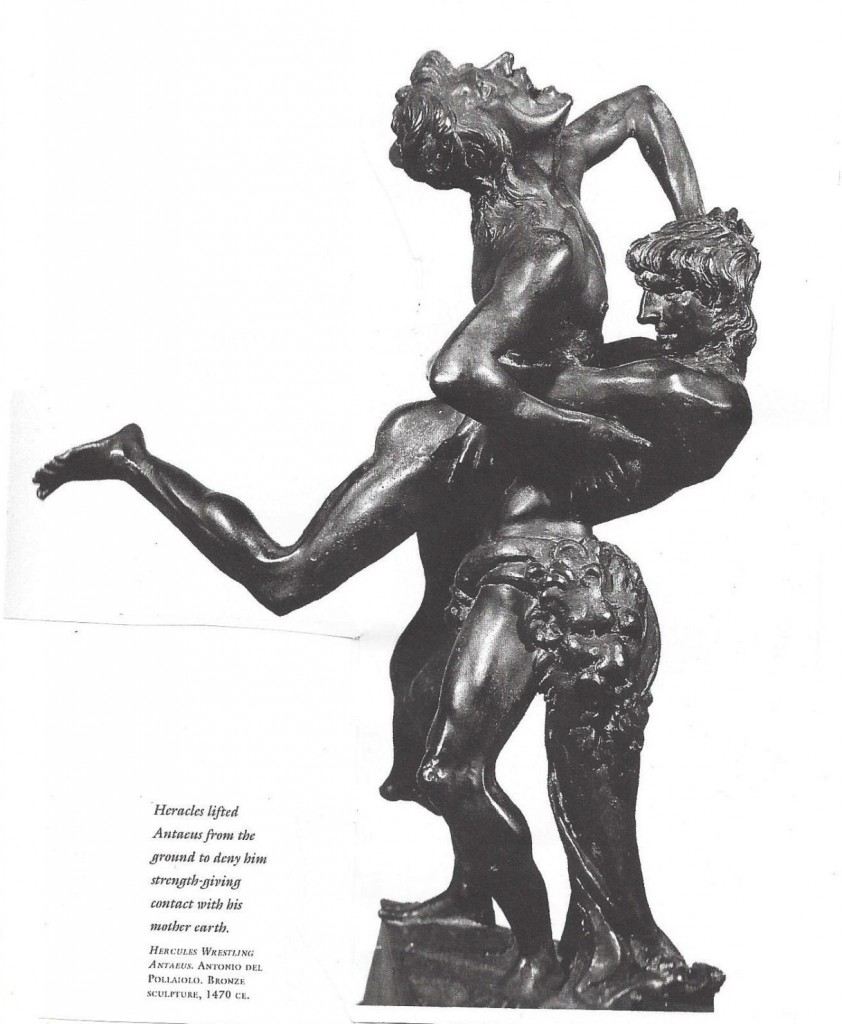

Today would have been Seamus Heaney’s 75th birthday and to celebrate that celebrated absence we offer an essay by Patrick J. Keane who does what the best critics do: he goes straight to the heart of the man through the poems and thence to the poems again. In 1972, Heaney famously and controversially moved from the bloody ground of Northern Ireland to Wicklow in the Republic, abandoning outright political action and commitment for a more contemplative and poetic life. He did not make this decision easily, and out of his personal struggle came the poems in North, what Keane calls his “most powerful and controversial collection.” Keane takes us through Heaney’s discovery of the famous “bog people” and the mythic method of poetic argument, his identification with the dispossessed peoples and the people of the earth, into the complex battle between Hercules and Antaeus (whose strength was always renewed by contact with mother earth) and finally to crucial culminating poem “Exposure,” a poem that begins

It is December in Wicklow:

Alders dripping, birches

Inheriting the last light,

The ash tree cold to look at.

dg

1

Had he lived, Seamus Heaney would have been 75 on April 13, 2014. For poetry lovers and, even more, for those who came to know him as a warm and generous human being, it’s hard to believe that that magnanimous presence is gone. Hard to believe, too, that it is almost 40 years since the publication of his most powerful and most controversial collection. When North appeared, in 1975, it was greeted enthusiastically by major critics as varied as Helen Vendler, Conor Cruise O’Brien, John Jordan, and Christopher Ricks. But strong reservations, politically-related and having to do with Heaney’s use or alleged misuse of archeology and myth, were expressed by Ulster writers Edna Longley and Ciaran Carson, among others. The hostility of some poets and critics in Northern Ireland was influenced, or at least complicated, by the fact that Heaney had left his native province in 1972, just as the sectarian conflict was intensifying.

In the wake of Bloody Sunday, in January 1972, when British paratroopers fired into a crowd of Catholic civil rights marchers in Derry, killing twelve and wounding thirteen, a consensus had understandably solidified among the Catholic minority in the North. In one of their sustained interviews, conducted over a half-dozen years, Heaney told Dennis O’Driscoll that one of the reasons he moved from Belfast to Wicklow in the Republic was precisely to “get away from the consensus culture that had built up among us.” That culture would be reflected a few years later in the response from the North to North. “I’d left the party,” as Heaney put it to O’Driscoll, “and that complicates things for everybody, for the one who goes as well as the ones who stay. You get my side of that in the last poem of the book, ‘Exposure’.” {{1}} [[1]]O’Driscoll, Stepping Stones: Interviews with Seamus Heaney (NY: Farrar, Straus and Giroux, 2008), 159-60. (Henceforth cited parenthetically as SS).[[1]]

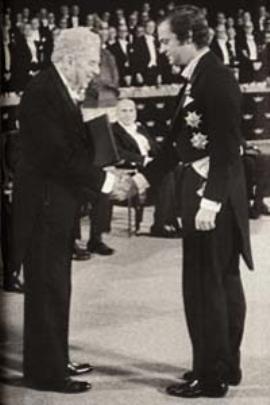

The present essay takes its thematic and structural cue from Heaney’s specific response to a question. Asked about the “new direction” his poetry had taken after the “archeological and mythological” emphases in North, Heaney observed that such a “new direction is already being followed in North, in poems like ‘Hercules and Antaeus’ and ‘Exposure’” (SS, 162). The former, which closes Part I of North, revisits and revises “Antaeus,” the poem that had opened Part I; and the reconsiderations, or second thoughts, implicit in that revision prepare us for “Exposure,” which brings to a close the volume as a whole, including the more discursive and directly political poems of Part II. In Heaney’s canon, from the beginning through his death in August 2013, there is no more crucial text, personally and politically, than “Exposure,” not only the final poem in North, but the one poem he chose to stress—quoting it almost in full (OG, 419-20)—in “Crediting Poetry,” his 1995 Nobel Prize Acceptance speech.{{2}}[[2]]“Crediting Poetry,” in Seamus Heaney, Opened Ground: Selected Poems 1966-1996 (NY: Farrar, Straus and Giroux, 1998), 415-30. Opened Ground is cited parenthetically throughout as OG.[[2]]

Heaney was very conscious of “the artistic doubleness,” the “double aspect,” of North. He continued, in the Stepping Stones interview, to say that “the Hercules poem” is, “for all its mythy content” (characteristic of Part I), expressed in “plain speech”—the language of Part II. (SS, 160, 162). Yet “Hercules and Antaeus,” a literally pivotal poem, remains “mythy.” Like “Antaeus,” the poem it echoes in order to alter, it derives, obviously, from Greek mythology. In general, however, Heaney famously drew in North on a mythology and archeology rooted in Northern Europe. In order to address the horrors unfolding in his native province in the late 1960s and early 1970s, Heaney in effect played a variation on what T. S. Eliot had called, in his cogent 1923 Dial review of Ulysses, “the mythical method.” Joyce had paralleled Homer’s Odyssey with the events of his own pedestrian epic of Leopold Bloom, and so taken, said Eliot, “a step toward making the modern world possible for art,” a step toward “order and form.”

In using “myth,” Eliot went on, “in manipulating a continuous parallel between contemporaneity and antiquity,” Joyce was “pursuing a method which others must pursue after him,” not as “imitators,” but as “a way of controlling, of ordering, of giving a shape and a significance to the immense panorama of futility and anarchy which is contemporary history.” Eliot was keenly aware (as was Joyce himself) of his debt to Ulysses in The Waste Land. He was also aware that Yeats had reanimated Cuchulain, made his Maud Gonne a modern Helen of Troy, set his apocalyptic rough beast slouching toward an anything-but Christian rebirth in Bethlehem, and had, in his great poetic sequence “Nineteen Hundred and Nineteen,” juxtaposed the Persian destruction of the “ingenious lovely things” of Athenian civilization with the eruption of modern barbarism. Eliot was right to note: “It is a method already adumbrated by Mr. Yeats, and of the need for which I believe Mr. Yeats to have been the first contemporary to be conscious….Instead of a narrative method, we may now use the mythical method.”{{3}} [[3]]Eliot, “Ulysses, Order, and Myth.” The Dial 75 (November 1923); cited from Selected Prose of T. S. Eliot, ed. Frank Kermode (NY: Farrar, Straus and Giroux, 1975), 175-78 (177).[[3]]

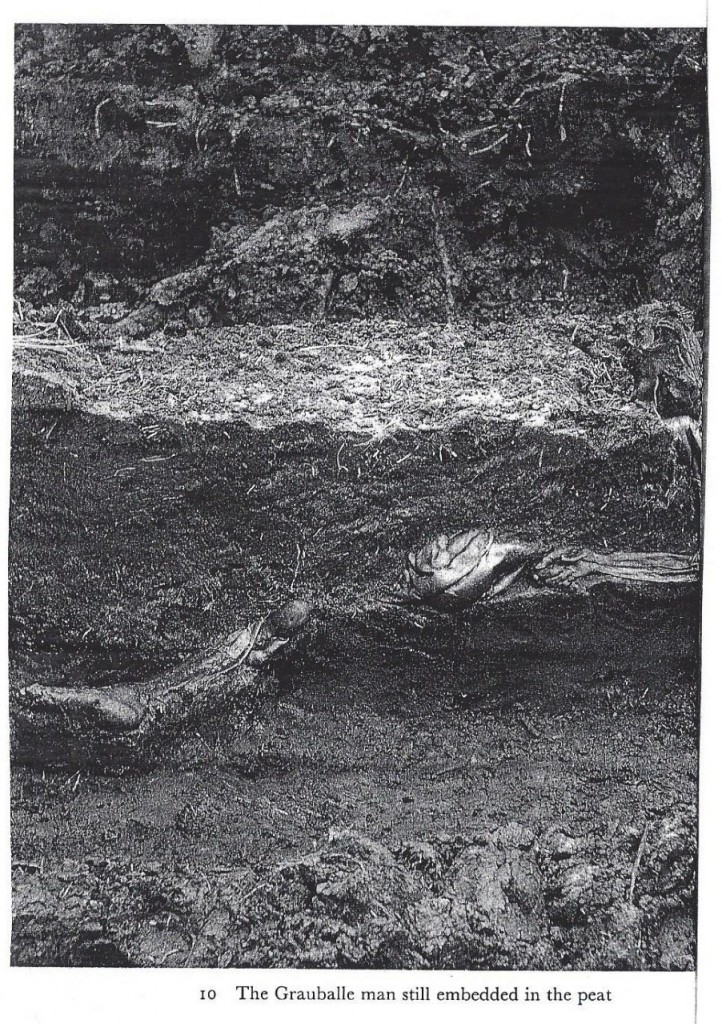

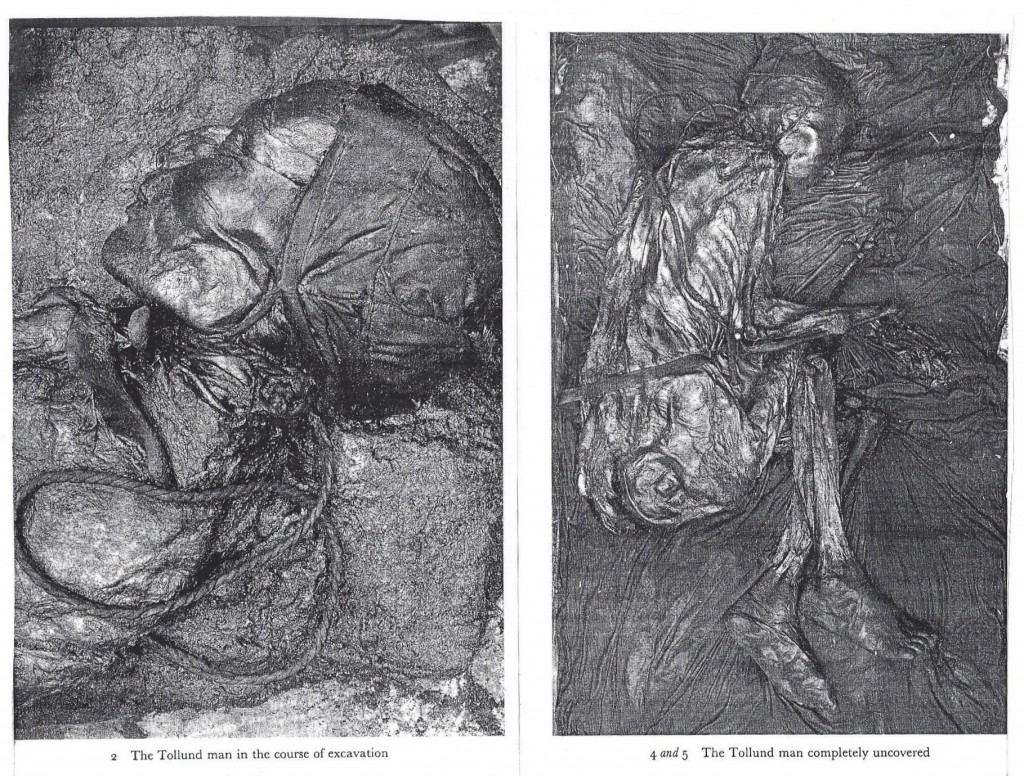

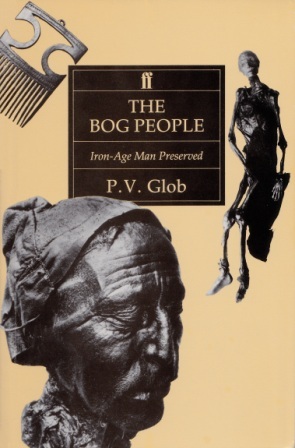

In North, Heaney uses the mythical method to engage the anarchic panorama presented by the sectarian, political, and deep-rooted cultural conflict in Northern Ireland that erupted in the late sixties and continued well beyond the publication of North in 1975. Though a lapsed Catholic, Heaney continued to identify with those in his tradition, “my wronged people.” But he realized, as he says in the second half of North, in the poem “Whatever You Say Say Nothing,” that the “liberal papist note sounds hollow,” and that “the ‘voice of sanity’ is getting hoarse” (OG, 123). Clichéd rhetoric at the journalistic level of daily reportage, or echoing (or bemoaning) the simplifications imposed by rival sectarian ideologies, was inadequate to the atrocities occurring on the ground. In a dramatic move, Heaney set the contemporary Troubles in the deep historical context provided by P. V. Glob’s text and “unforgettable photographs” in The Bog People, a book that deeply moved Heaney as a man and creatively galvanized him as a poet.

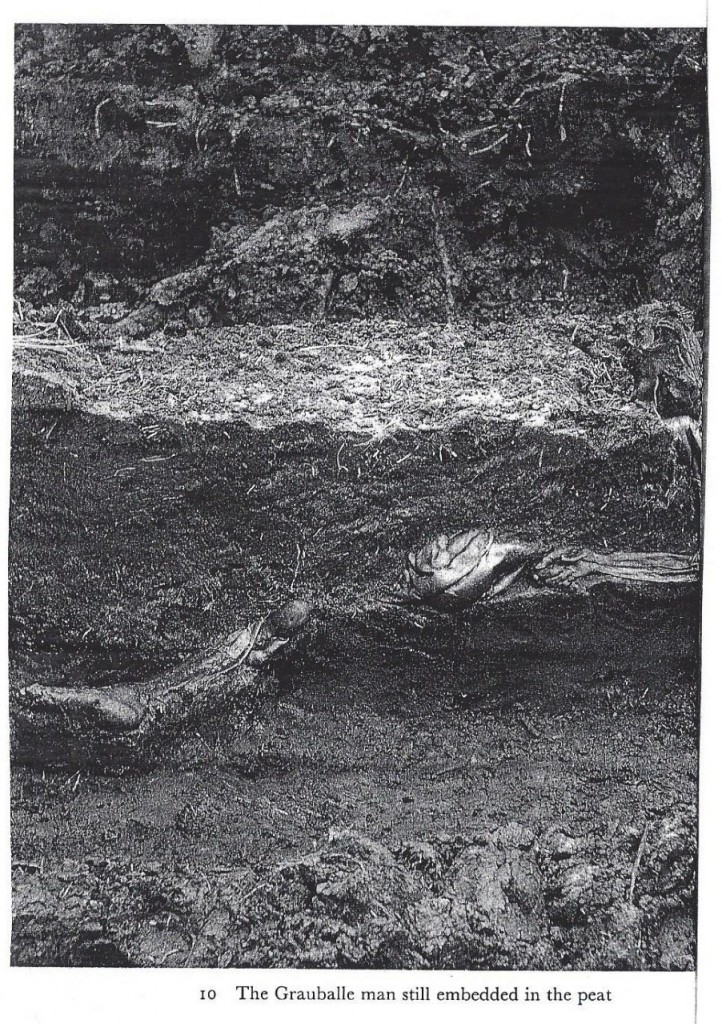

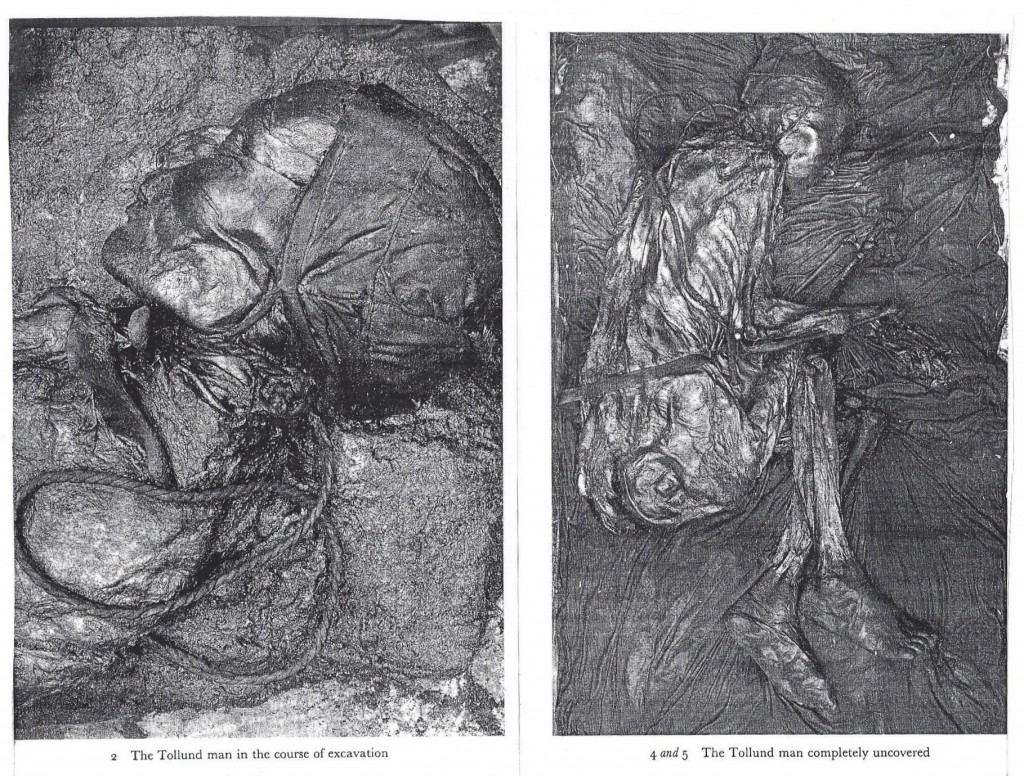

Attracted by its title, he’d bought The Bog People as a Christmas present for himself in 1969, the year the book was published. A “line was crossed,” he told O’Driscoll (SS, 157), with “The Tollund Man,” published in Wintering Out (1972), the collection immediately preceding North. When he wrote that poem’s first line, “Some day I will go to Aarhus” (OG, 62), he felt that he was in “a new field of force.” He compared Glob’s book to a gate. “The minute I opened it and saw the photographs, and read the text, I knew there was going to be yield from it.” Even, he insisted, if there had been no Northern Troubles, he would still have been drawn to the stunning pictures and descriptions of the Iron Age bodies exhumed from the peat. There was a hiatus, but he knew that he was not finished with The Bog People. “I didn’t really ‘go back’ to the book,” he said in 2006 or so, “because it never left me. And still hasn’t” (SS, 157-58).

Heaney later wished that, in public readings, he had played down his application of the bog material to the political situation in the North. It “would have been better…for me and for everybody else if I had left [the poems] without that sort of commentary.” Above all, it “would have been better for the poems,” which had their own “biological right to life.” That was the “point and remains the point and I never had the slightest doubt about them in that regard” (SS, 159). Nevertheless, Heaney obviously saw current atrocities mirrored in the preserved bodies of those murdered Iron Age victims (the Bog Queen, Tollund Man, Grauballe Man): all part of the blood-saturated, “skull-capped ground” of the “old man-killing parishes” of the Scandinavian and Irish North; while the adulteress of “Punishment,” unearthed from a bog in Germany, was even more controversially identified by Heaney with his tribe-betraying sisters, heads shaved and “cauled in tar” for fraternizing with British soldiers in contemporary Belfast. (OG, 62, 113)

As deployed in North, Heaney’s archeological-mythical method was unquestionably powerful and attention-getting. But the primary challenge remained: to concentrate on getting things right, not in deeds, but in words and images—befitting emblems of adversity that would record what happened, bear witness without exploiting the tragedy of the Troubles, and remain true to oneself. This demanding task, confronted in the bog poems and in the more immediately political poems of the “Singing School” sequence in North, culminates in “Exposure.” But the trajectory begins (once we are past the two exquisite dedicatory lyrics) with the first of the two poems centering on the mythic and symbolic combat between Antaeus and Hercules.

.

2

Some familiarity with these titular figures from Greek mythology is required to grasp what Heaney retrospectively came to regret in the case of the bog poems: the application to the political situation in Northern Ireland at the time. The Hercules-Antaeus conflict is also relevant to his own position at the time, which was anything but static. During the Troubles, quoting Czelaw Milosz’s Native Realm, Heaney said of himself, in his poem “Away From It All”:

I was stretched between contemplation

of a motionless point

and the command to participate

actively in history.{{4}}[[4]]Station Island (NY: Farrar, Straus and Giroux, 1984), 17.[[4]]

It was a variation on an old theme. As Henry Hart has observed, “at the root” of the work of this “poet of contrary progressions” is a “multifaceted argument with himself, with others, with sectarian Northern Ireland, with his Anglo-Irish [poetic] heritage, and with his Roman Catholic, nationalist upbringing on a farm in County Derry.”{{5}} [[5]]Hart, Seamus Heaney: Poet of Contrary Progressions (Syracuse: Syracuse UP, 1992), 2.[[5]] In that dialectical context, the perennial combat embodied in the mythic wrestling match between Hercules and Antaeus becomes emblematic of the dynamic between the first and “second thoughts” of Seamus Heaney himself, “stretched between” contemplation and the pressure to participate actively, a man of “two minds” both poetically and politically. In “Terminus” (from The Haw Lantern, 1987), Heaney, graphically illustrating his double-mindedness, says he “grew up in between,” describing himself in Part 1 of the poem as suspended between past and present, between the native earth of the Derry farm of his childhood, and the machinery of the modern world:

When I hoked there, I would find

An acorn and a rusted bolt.

If I lifted my eyes, a factory chimney

And a dormant mountain.

If I listened, an engine shunting

And a trotting horse.

Is it any wonder when I thought

I would have second thoughts? (OG, 272)

Both in her 1998 book, Seamus Heaney, and in her not-yet-published 2014 obituary, Helen Vendler emphasizes these “second thoughts,” even going so far, in the book, as to have a “Second Thoughts” section as a sort of postscript or coda to each chapter. The theme of reconsideration is embodied in Heaney’s two treatments of the Hercules-Antaeus story, and their placement. Readers of Opened Ground, the poet’s own selection of verse from 1966-1996, will be misled by the Contents page, which indicates that “Antaeus” (the only poem in Opened Ground parenthetically dated) appeared in his first collection, Death of a Naturalist. It didn’t. Though it was written in the year that inaugural volume was published (1966), it first appeared in print in 1975 in North, immediately following “Mossbawn,” incorporating the two introductory ut pictura poeisis (Vermeer and Brueghel, respectively) poems dedicated to his Aunt Mary.

That warm domestic and pastoral preamble (OG, 93-94), twinned poems of love (“like a tinsmith’s scoop/ sunk past its gleam/ in the meal-bin”) and benign communal activity (potato seed-cutters in a Brueghel-like “frieze/ with all of us there, our anonymities”) is in striking contrast to the violent subject-matter of most of North: violence introduced by the poem that opens Part I of North, “Antaeus.” Heaney’s second poem on the struggle between the two Greek heroes, “Hercules and Antaeus,” closes Part 1. In Opened Ground, Heaney evidently wanted to put some distance between “Antaeus” and the poems he selected in 1998 to represent his work in North—understandably, since there had indeed been second thoughts. “Hercules and Antaeus,” in which the poet grudgingly recognizes the inevitable triumph of the Hercules figures of the world, not only revisits but in part reverses the 1966 poem in which he clearly identified with “Antaeus.” Before proceeding, we should pause for a backward glance at both Greek heroes.

The son of Zeus and Alcmene, a mortal woman, Heracles (Hercules is the Latin form of the name) was intended by his father to lord it over all others. Though he became the greatest and most popular hero in Greek mythology, renowned for both brawn and brains, he had obstacles to overcome from the outset. The jealous wife of Zeus, Hera, unsuccessful in preventing Heracles’ birth, tried (Pindar tells us) to destroy him as an infant, sending two snakes to strangle him in his cradle. Little Heracles strangled the snakes instead. Hera later contrived to have the destiny Zeus intended for his son conferred instead on the king of Argos, Eurystheus, to whom Heracles would eventually become subject, forced (as punishment for the murder of his wife and children during a Hera-inflicted fit of madness) to perform the famous Twelve Labors.{{6}}[[6]]Among his many heroic exploits, Heracles led the Theban army to victory in battle, and was rewarded by the king, Creon—the tyrant who has rebellious Antigone buried alive (Heaney would later publish a version of Sophocles’ great tragedy Antigone under the title The Burial at Thebes). In gratitude, Creon gave Heracles in marriage his daughter Megara, with whom he had three children. When he regained his senses after killing his family, Heracles was commanded by the priestess of Apollo to obey Eurystheus, who assigned him the Twelve Labors (athloi: contests undertaken for a prize).[[6]] In Book 11 of the Odyssey, the ghost of Heracles tells Homer’s hero of his suffering: “Son of Zeus that I was, my torments never ended,/ forced to slave for a man not half the man I was:/ he saddled me with the worst heartbreaking labors.” Those labors included, among others, killing the Nemean Lion, cleansing the Augean stables, and (the task he specifically mentions to Odysseus), retrieving the three-headed hound Cerberus from Hades; “no harder task for me, he thought,/ but I dragged the great beast up from the underworld to earth.”{{7}}[[7]]Homer: The Odyssey, trans. Robert Fagles (NY: Viking, 1996), 269-70. Book 11: 621-24.[[7]]

Prior to hauling Cerberus up from Hell, Heracles had been tasked by Eurystheus to find and bring to him the golden apples originally given (by Ge, mother of Antaeus) to Hera to celebrate her marriage to Zeus. The apples were secreted in the distant Garden of the daughters of Atlas, the Hesperides, where they grew from a Tree guarded not only by these three singing nymphs, but by the hundred-eyed serpent Ladon, coiled protectively about the trunk. In the most prominent variation on the legend, Heracles, wandering about seeking advice on the location of the Garden, encounters Prometheus, chained to the rock in the Caucasus, waiting by night for the eagle that returned daily to feed on his liver. When Heracles shoots and kills the eagle with his bow, a grateful Prometheus advises his savior to enlist his brother Atlas, who knows the location of the Garden. Atlas was also being punished by Zeus, condemned to support the sky on his back forever in order to keep heaven and earth apart. When he finally finds cloud-mantled Atlas, Heracles asks for his help in getting the apples. The Titan agrees, providing that Heracles, in exchange, will shoulder his burden. Heracles agrees. But when Atlas returns with the apples, clever Heracles tricks him into resuming his burden and departs with his prize.

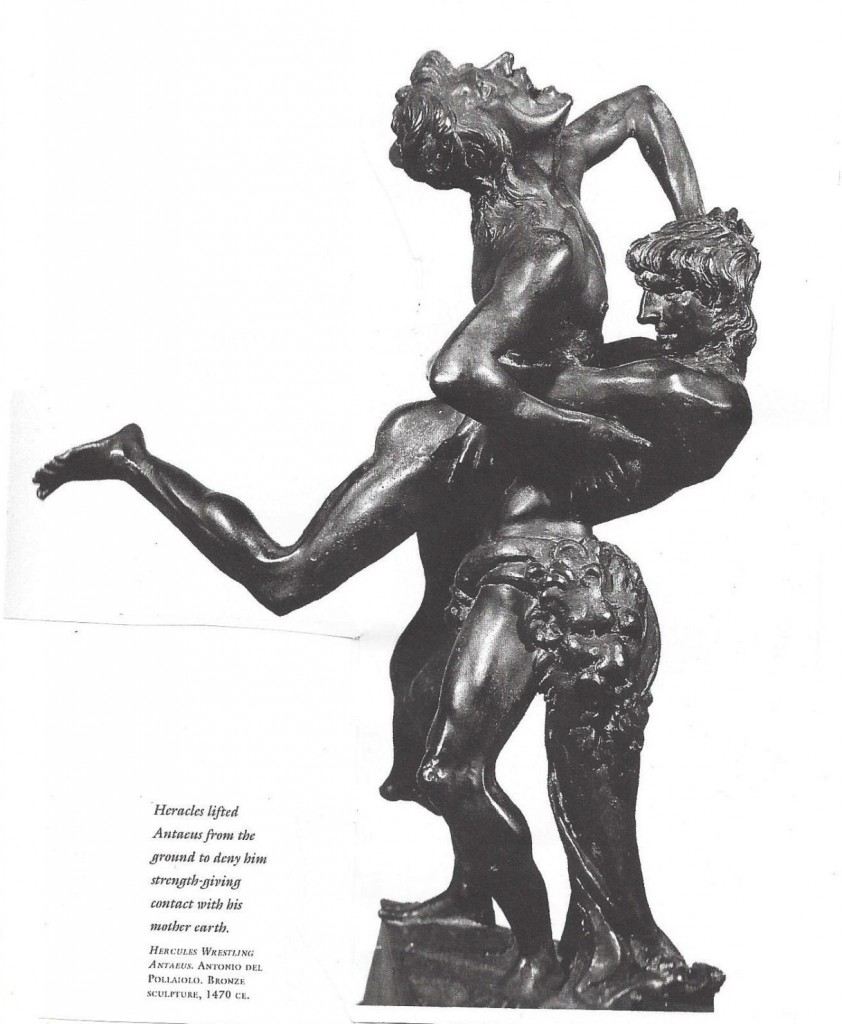

In his long and meandering journey to the remote Garden of the Hesperides, Heracles, in addition to helping Prometheus, engaged and conquered two dangerous enemies in Northern Africa: the king of Egypt, Busiris, and the less tyrannical but even more formidable king of Libya. This was the invincible wrestler, the giant Antaeus, son of the Earth-goddess Ge and the sea-god Poseidon. Antaeus was always victorious in his matches because, when he was thrown to the ground, the Earth, his mother, renewed his strength. In their famous match, Heracles, unaware at first of that special relationship, started by wrestling Antaeus in the normal way. But, smart as he was powerful, he quickly realized what was going on. Lifting the giant up, Heracles held Antaeus aloft in the air, weakened him, and slowly crushed him to death with his bare hands. In his two poems on the subject, double-minded Seamus Heaney identifies in the first with with the earthy Antaeus, then, reluctantly, acknowledges the power and intelligence of Hercules.

.

3

The 1966 “Antaeus” begins with a probable echo (one among several, to which I’ll return) of Heaney’s predecessor and fellow Irishman and Nobel laureate, W. B. Yeats. Heaney would seem to have in mind as well lines from Robert Frost—his “favorite poet,” he later confided to a surprised Helen Vendler. In the two concluding quatrains of “To Earthward” (1923), Frost yearns for an Antaeus-like relationship with the earth, a joyous contact so intense as to include pain and tears, “the aftermark/ Of almost too much love.”

When stiff and sore and scarred

I take away my hand

From leaning on it hard

In grass and sand,

The hurt is not enough:

I long for weight and strength

To feel the earth as rough

To all my length. {{8}}[[8]]The Poetry of Robert Frost (NY: Holt Rinehart and Winston, 1969), 227.[[8]]

And here are the opening lines of Heaney’s gravitational poem, also written in quatrains:

When I lie on the ground

I rise flushed as a rose in the morning,

In fights I arrange a fall on the ring

………..To rub myself with sand

That is operative

As an elixir.

Antaeus’ earth-connection is chthonic and natal. “I cannot be weaned/ Off the earth’s long contour, her river-veins,/ Down here in my cave,” he says. “Girdered with root and rock/ I am cradled in the dark that wombed me,/ And nurtured in every artery.” The final two quatrains introduce Heracles—supposedly just one of many challengers (“Let each new hero come…”), but identified by the references to the golden apples, to Atlas, and to the fatal wrestling match:

Let each new hero come

Seeking the golden apples and Atlas.

He must wrestle with me before he pass

………..Into that realm of fame

Among the sky-born and royal:

He may well throw me and renew my birth

But let him not plan, lifting me off the earth,

………..My elevation, my fall. (OG, 15)

It is hard to gauge the tone (pride, bravado, fear, petition?) in the punning and paradoxical final lines, in which Antaeus envisages and yet resists Heracles’ victorious strategy in the received myth. Let my opponent “not plan,” says Antaeus, even in elevating me off the earth, “my fall.”

Renewal in descent is a Yeatsian theme as well. In his late, summing-up poem, “The Circus Animals’ Desertion,” the “foul” heart in which the ladderless Yeats at last “must lie down” is the fecund source of the artist’s creativity, enabling him to be, as Heaney’s Antaeus puts it, “nurtured in every artery.” But the closer Yeatsian parallel to Heaney’s “Antaeus” occurs in a related summing-up poem, “The Municipal Gallery Revisited” (also written in 1938). Yeats had identified (in the Preface to A Vision) with another Greek hero, terrestrial Oedipus, who “descended into an earth riven by love,” rather than with celestial Christ, who ascended into the abstract heaven. (Yeats is recalling his “translation” of the Messenger’s speech in Oedipus at Colonus; Heaney has described as one of “the things I’ve done with most relish,” his own version of the Messenger’s account of Oedipus disappearing, “assumed into earth rather than into heaven” [SS, 472]). In the Municipal Gallery poem, Yeats, asserting the gravitational pull of his art and cultural nationality alike, alludes directly to the Antaeus myth, applying it to himself and his principal Abbey-Theatre co-workers. Along with that earthy aristocrat and collector of Irish folklore, Lady Augusta Gregory, and “that rooted man” John Millington Synge, Yeats thought

All that we did, all that we said or sang

Must come from contact with the soil, from that

Contact everything Antaeus-like grew strong.{{9}}[[9]]W. B. Yeats: The Poems [henceforth, YP], ed. Daniel Albright (London: Everyman’s Library, 1992), 367-68, and 395, for “The Circus Animal’ Desertion”); A Vision (London: Macmillan, 1962 [1937]), 27-28.[[9]]

Early Heaney would agree. Like Antaeus, son of Mother Earth, the poet of Death of a Naturalist (1966) and Door into the Dark (1969) seemed an instinctual and earth-centered child of the natal soil. In an essay published in 1980, five years after North, he, too, like Yeats, described Synge as one who, Antaeus-like grew strong, having discovered in his experience on the Aran Islands a tangible “power-point.” Like Heaney himself in his archeological digging into the remote pre-Christian past in North, Synge, “grafted to a tree that had roots touching the rock bottom, …had put on the armour of authentic pre-Christian vision which was a salvation from the fallen world of Unionism and Nationalism, Catholicism and Protestantism, Anglo and Irish, Celtic and Saxon—all those bedevilling abstractions and circumstances.”{{10}}[[10]]Heaney, “A Tale of Two Islands: Reflections on the Irish Literary Revival,” in Irish Studies 1, ed. P. J. Drudy (Cambridge: Cambridge UP, 1980), 1-20 (9).[[10]]

.

4

But, however bedeviling and abstract, those antithetical forces could not be ignored or wholly transcended, and Heaney’s proclivity toward “second thoughts” would not allow him to rest with a too-easy “salvation” in the form of empathetic alliance with one side of the agon. As his cherished Robert Frost acknowledged, “I have been pulled two ways and torn in two all my life.”{{11}}[[11]]The Letters of Robert Frost, vol. 1 (of a projected 3), 1886-1920, ed. Robert Sheehy, Mark Richardson, and Robert Faggen (Cambridge: Harvard UP, 2013).[[11]]At the time he wrote that, in a 1915 letter, Frost was just five years older than the author of North. Though Heaney was similarly torn, Antaeus—his alter ego in the 1966 poem—was, for all his myth-defying insistence or petition, still a defeated figure. When he takes up the theme again, in the wake of the renewed violence in Northern Ireland beginning with Bloody Sunday in January 1972, Heaney concedes in advance the defeat of Antaeus at the hands, and head, of Heracles, a figure of superior strength and “intelligence.”

In the earlier poem, Antaeus had boasted that the challenger must wrestle with him before he could “pass/ Into that realm of fame//Among sky-born and royal.” That successful passage is acknowledged (repeating the very phrase) at the outset of the new poem—which is written in the third person and whose opening lines go on to allude to Heracles’ feats: from the precocious choking of the snakes sent to strangle him in his cradle, through his ingenious cleansing of the accumulated cattle-dung in the Augean stables, and his successful quest for the golden apples, culminating in his apotheosis, laden with earned prizes:

Sky-born and royal,

Snake-choker, dung heaver,

His mind big with golden apples,

his future hung with trophies,

Hercules has the measure

of resistance and black powers

feeding off the territory.

The forces of resistance whose “measure” has been taken—doubly “grasped”—by intelligent Hercules, a violent light-bringer, are primordial, instinctual “black powers/ feeding” off the nurturing soil, the native “territory.” Antaeus himself is introduced as “the mould-hugger.” In the earlier poem he had claimed, “I cannot be weaned off” the earth and its “cradling dark.” Now he is described as “weaned at last” from his Mother-Earth. In the past,

a fall was a renewal

but now he is raised up—

the challenger’s intelligence

is a spur of light,

a blue prong graiping him

out of his element

into a dream of loss

and origins—the cradling dark,

the river-veins, the secret gullies

of his strength

the hatching grounds

of cave and souterrain,

he has bequeathed it all

to elegists. Balor will die,

and Byrthnoth and Sitting Bull.

“Light”—masculine and intellectual—defeats the cradling “dark” that had, in the earlier poem, “wombed” and “nurtured” Antaeus. Now the intelligent but phallic and brutal “spur” and “prong” of Hercules has succeeded in “graiping” (an obscure but forceful Scots verb for lifting, perhaps derived from William Dunbar) Antaeus “out of his element” into a dream of “loss” and nostalgia for his chthonic “origins” in the mothering soil: the hidden river-veins, gullies, caves and underground networks that once nourished his strength, and over which Heaney lingers.

Heaney’s lingering identification with Antaeus and the poetic, cultural, and nationalist dimension of this poem are confirmed by a 1979 interview, in which he recalled a conversation with a “fine” British poet, but one with a “kind of Presbyterian light” about him, “essentially different from the kind of poet I am.” The “image” that came into Heaney’s mind after the conversation “was of me being a dark soil and him being a kind of bright-pronged fork that was digging it up and going through it.” In “Hercules and Antaeus,” he continued, “Hercules represents the possibility of the play of intelligence,” resembling the “satisfaction you get from Borges,” so “different from the pleasures of Neruda, who’s more of an Antaeus figure.” Such thinking, he says, “led into the poetry of the second half of North, which was an attempt at some kind of declarative voice.” In that voice, the victory of the trophy-laden conqueror, his “light” too Protestant and “Anglo” for Heaney to ever endorse, is registered, but with reluctance.{{12}}[[12]]John Haffendon, “Meeting Seamus Heaney,” reprinted in Viewpoints: Poets in Conversation. (London, 1981), 57-75. My colleague David Lloyd rightly insists that Hercules is “too Angloish for Heaney to get too near.” [[12]]

Forcefully severed from contact with the dark soil that is the source of his strength, Antaeus must lose, bequeathing his legacy to “elegists” lamenting the death of other indigenous fighters defeated and dispossessed by invaders. Heaney singles out mythic and historical losers, united by fate and alliteration: the one-eyed Irish god-king Balor, killed by the Tuatha de Danaan, the legendary invaders of Ireland; the Anglo-Saxon earl Byrthnoth, slain by Vikings in the massacre of his forces at the Battle of Maldon (991); and the chief of the Lakota Sioux, Sitting Bull, victor at Little Big Horn in 1876, but shot and killed by Indian police when, a decade and a half later, his followers tried to rescue him from reservation captivity. Transatlantic, but emblematic of all the native peoples overwhelmed in the inexorable advance of whites colonizing the American continent, Sitting Bull belongs in this trinity of the dispossessed and defeated—principal among whom are Heaney’s own “wronged people,” driven out or subjugated by the English invaders and planters, and still subject to violence and discrimination.

The final two stanzas present the victor in an iconic pose (archaic, but repeated from Churchill to “Rocky”), along with the transformation of the defeated into the topography and mythology of resurrection so often resorted to by the vanquished: arrogant “Hercules lifts his arms/ In a remorseless V,” his “triumph unassailed/ By the powers he has shaken,”

And lifts and banks Antaeus

High as a profiled ridge,

A sleeping giant,

Pap for the dispossessed. (OG, 121-22)

The defeated Antaeus is lifted, crushed to death, and banked, his profiled corpse becoming part of the ridged landscape. In both Native American (Ojibway) and Celtic mythology and popular legend, a Sleeping Giant will one day awaken to lead his defeated and disinherited people to triumph. This desperate cultural-political wish-fulfillment, applied to his own tribe in Northern Ireland, is spurned by Heaney, brutally and caustically, as “Pap for the dispossessed”: the sentimental mythology of false hope that simultaneously sustains and deludes an uprooted and oppressed people. Later, in Station Island, the ghost of James Joyce himself will advise Heaney to stop “raking at dead fires” and “rehearsing the old whinges at your age./ That subject people stuff is a cod’s game,/ infantile” (OG, 245). Though Heaney is not dismissing the reality either of oppression or of the need to rectify injustice, he is harshly critical of what Neil Corcoran succinctly describes as a subject people’s “hopeful but puerile” mythology. Yeats, too, in Celtic fin-de-siècle poems like “The Secret Rose” and “The Valley of the Black Pig, and, more obliquely in “The Second Coming,” had reminded us that oppressed people always dream apocalyptic dreams of deliverance, of what the distinguished Quaker philosopher Rufus M. Jones has memorably called “the fierce comfort of a relief expedition from the skies.”{{13}}[[13]]Corcoran, Seamus Heaney (London and Boston: Faber & Faber, 1986), 100. Jones, The Eternal Gospel (NY: Macmillan, 1938), 5. For the Yeats poems, see YP, 87, 83, 235. [[13]]

In that climactic line, “Pap for the dispossessed,” Heaney, conceding victory to Hercules, refuses to dwell on either the nostalgic “dream of loss/ and origins,” or the apocalyptic pipedream of the projected awakening of a “sleeping giant.” In Greek myth, Heracles will himself eventually be defeated, poisoned by the toxic shirt of the centaur Nessus. Though that dark future offers no comfort in this poem, it is also true that the combat between what is antithetically represented by Heaney’s Hercules and Antaeus (a spur of light/earthy darkness, “male” reason/ “female” instinct, victory/defeat) is itself a transitional phase, a “stepping stone” in a larger and more complex dialectic, both poetic and political. The forces symbolized in “Hercules and Antaeus” will wrestle again, and on a far more nuanced level, in the culminating poem in North, “Exposure.” By “bidding farewell to the chthonic elegiac myth of Antaeus, by finding something to praise in the ‘spur of light’ in ‘the challenger’s intelligence,’ Heaney,” writes Helen Vendler, “opened himself to the more authentic—if more dubious and shifting—figures animating “Exposure”—figures of exile, of flight, of sequestration and, above all, of second thoughts, ‘weighing and weighing,’ as he says, ‘my responsible tristia’.”{{14}}[[14]]Vendler, Seamus Heaney (Cambridge, Mass.: Harvard UP, 1998), 89-90.[[14]]

.

5

Seamus Heaney began his Nobel Prize Acceptance speech, just as he had begun “Terminus” eight years earlier, by presenting himself as having grown up “in between”; “in suspension,” he says in the speech, “between the archaic and the modern.” His life as a “pre-reflective” child safely insulated from the outside world in a crowded traditional thatched farmstead was “an intimate, physical, creaturely existence in which the sounds of the horse in the stable beyond one bedroom wall mingled” with other sounds—“rain in the trees,…a steam train rumbling along a railway line one field back from the house.” This was during World War II, and so, conveyed by the wind-stirred wire leading from atop a chestnut tree to the family radio, the sounds included the voice of a BBC newsreader announcing in “resonant English tones…the names of bombers and of cities bombed, of war fronts and army divisions,” and intoning as well “those other solemn and oddly bracing words, ‘the enemy’ and ‘the allies’.” (OG, 416)

That child in the bedroom listening simultaneously to sounds of the pastoral and modern worlds was “already being schooled for the complexities of his adult predicament”: a future involving the conflict between the Provisional IRA, British troops, and loyalist paramilitaries during the renewed Troubles, centered in Northern Ireland but radiating out to bombings in Dublin and London. A no-longer “pre-reflective” child, Heaney was now an adult who would, as he told his audience in Stockholm, have to “adjudicate” among “promptings” that were

variously ethical, aesthetical, moral, political, metrical, skeptical, cultural, topical, typical, post-colonial and, taken all together, quite impossible. So it was that I found myself in the mid-nineteen-seventies in another small house, this time in County Wicklow south of Dublin, with a young family of my own and a slightly less imposing radio set, listening to the rain in the trees and to the news of bombings closer to home…feeling challenged yet steadfast in my non-combatant status when I heard, for example, that one particularly sweet-natured school friend had been interned because he was suspected of having been involved in a political killing. (OG, 418)

In August 1972, the year that had begun with the second Bloody Sunday, when British paratroopers killed and wounded the Catholic civil rights marchers in Derry, Heaney resigned his teaching post at Queens University in Belfast, moving with his wife and two young sons to Wicklow in the Republic. It was, he has acknowledged, the “most intense phase” of his life, “and not just of the writing life.” Referring to his family as well as himself, he told O’Driscoll, “we were at a turning point,…exposed and ready in a new way.” He had “no more alibis. That much was clear the first morning I took the children” to their new school “and the headmaster wrote ‘file’ [poet] in the column of the rollbook where he had to enter ‘Occupation of Parent.’ No more of your ‘lecturer’ or ‘teacher’” (SS, 156). They settled in “Glanmore,” a cottage (formerly the gatekeeper’s on the Synge estate) rented to them by their friend, the Synge scholar Anne Saddlemeyer. As noted earlier, the decision, much commented on in the media, was criticized by some Northern Catholics, including fellow writers, who felt that the poet best equipped to be an engaged spokesman for “their side” had abandoned them. In these circumstances, says Heaney in the Nobel Prize speech, what “I was longing for was…a way of crediting poetry without anxiety or apology.” It was then, he says (OG, 419), that “I wrote a poem called ‘Exposure’.”

Aside from “Punishment,” in which he accuses himself of complicity and passivity in the tribal vengeance exacted against his “sisters” brutally punished for fraternizing with British soldiers, “Exposure,” the sixth and final poem in the sequence “Singing School” in North, is the most controversial poem in Heaney’s most controversial and powerful collection. Epitomizing the rival claims of the private and public voice, of art and action, of poetry and political engagement, “Exposure” traces several “exposings.” The first is to the natural elements in a rural environment. The poem, written, like “Hercules and Antaeus,” in unrhymed quatrains, begins:

It is December in Wicklow:

Alders dripping, birches

Inheriting the last light,

The ash tree cold to look at.

In this damp, darkening, low-wicked end of the year, there were other cold looks. The second “exposing” was to the unaccustomed criticism already mentioned, both private and in terms of the media publicity occasioned by the decision to move to the Republic. The poet is critical himself—at least, as in the case of Horatio on the battlements in Hamlet, “a part of him.” In an image that will recur in the poem’s final line, he refers to the opportunity to possibly make a difference at home as “A comet that was lost,” and should at least

be visible at sunset,

Those million tons of light

Like a glimmer of haws and rose-hips,

And I sometimes see a falling star.

If I could come on meteorite!

Instead I walk through damp leaves,

Husks, the spent flukes of autumn,

Imagining a hero

On some muddy compound,

His gift like a slingstone

Whirled for the desperate.

Instead of a wrestling Antaeus, we have a stone-slinging potential Cuchulain or David defending his people against physically superior (Goliath-like) strength. Heaney’s “gift,” though weapon-like, would be (as in his canon-opening poem, “Digging”) that “pen” mightier than sword or gun (or slingshot). But the “desperate” here are the same “dispossessed” battening on “pap” in “Hercules and Antaeus.” In any case, it is all a fantasy. The million-tonned luminous comet is already “lost,” its glimmering roseate track not even “visible at sunset”; the lesser “falling star” is glimpsed only “sometimes”; and the recluse self-exiled in the Wicklow woods is, in this declension, reduced to hoping for the diminished excitement of coming upon “meteorite.”

Walking through “damp leaves,” the husks of an “autumn” as “spent” as the meteorite, and merely “imagining” himself a potentially salvific “hero,” Heaney sounds remarkably like the middle-aged Yeats of The Wild Swans at Coole, shuffling among the littering autumnal leaves and burning “damp faggots” while, in contrast, a man of action—Irish Airman Robert Gregory, driven by a lethal and “lonely impulse” to hurl himself into combat—“may consume/ The entire combustible world” in the “flare” of a single courageous if reckless decision. Like Heaney, who presents himself in this poem “weighing and weighing” options, Yeats’s Airman claims to have “balanced all, brought all to mind.” But the fighter-pilot impulsively leaps into his “tumult in the clouds,” while Heaney and Yeats “sit,” or walk through “damp leaves.” And yet one senses, at the deepest level, that for both poets, however they may momentarily envy and even glorify it, the role of the combustible “hero” is, in the final weighing, just more infantile pap.{{15}}[[15]]Ostensibly pure hero worship, both “An Irish Airman Foresees His Death” and “In Memory of Major Robert Gregory” (YP, 181-85) hint at subversive caveats.[[15]]

In the next two stanzas, the media exposure attending Heaney’s controversial move to the seclusion and safety of the Republic is made more intimate by the many-faceted “counseling” of friends (whether well-intentioned or the equivalent of Job’s comforters) and the more blunt hatred of ideological enemies, whose “anvil brains” generate more heat than sparks of light:

How did I end up like this?

I often think of my friends’

Beautiful prismatic counselling

And the anvil brains of some who hate me

As I sit weighing and weighing

My responsible tristia.

For what? For the ear? For the people?

For what is said behind backs?

The Latin word signals a double-echo: an allusion to another internal émigré, Osip Mandelstam in the Stalinist Soviet Union, whose poems in exile, titled Tristia, in turn echoed the Tristia of Ovid, exiled by Augustus from Rome. But “for what,” Heaney asks himself, does he sit weighing and weighing incompatible responsibilities? He momentarily casts doubt even on the claims of poetry, in terms both of its adequacy in the face of the atrocities in the North and in purely aesthetic terms: the artistic labor required to create sounds to please a discerning “ear.” Feeling, as he said in the Nobel Prize speech, “challenged yet steadfast,” he implicitly resists as well civic responsibility in the form of politically engaged labor on behalf of “the people,” and spurns, though acutely sensitive to it, the sniping of those who talk behind one’s back.

But there remains self-criticism and the final and most important “exposure”: the revelation of his own deeply-conflicted feelings and thoughts. He hears, in the symbolic utterance of the rain through the alders (the familiar rain-in-the-trees image with which the poem had opened), self-accusation and a nagging fear—since each raindrop recalls the “diamond absolutes” beyond endless weighing of alternatives—that he may be a less-than-noble escapist whose quietist quest has caused him to dodge the violence and miss a momentous chance:

Rain comes down through the alders,

Its low conducive voices

Mutter about let-downs and erosions

And yet each drop recalls

The diamond absolutes.

I am neither internee nor informer;

An inner émigré, grown long-haired

And thoughtful; a wood-kerne

Escaped from the massacre,

Taking protective colouring

From bole and bark, feeling

Every wind that blows;

Who, blowing up these sparks

For their meagre heat, have missed

The once-in-a-lifetime portent,

The comet’s pulsing rose. (OG, 135-36)

.

6

“Exposure,” in which Heaney puts extraordinary pressure on himself, is an intimate self-examination and meditation on what Robert Frost famously called “the road not taken.” But against the vacillation and conflicted thoughts that led him both to self-protectively escape “the massacre” and to miss the not-taken and once-only opportunity to stay in the North and perhaps even make a difference politically, we have to weigh, as Heaney may well have, not only the nuanced subtext of sedentary Yeats’s ostensibly unflattering contrast of himself to heroic Robert Gregory, but the older poet’s insistence, in “The Second Coming,” that it is the “best” who lack conviction, while “the worst/ Are full of passionate intensity” (YP, 235). In addition, though they give off but “meagre heat” compared to the comet’s “million tons of light,” the “sparks” to which Heaney refers in the final stanza are poetic sparks.

According to Heaney in a 1997 interview with fellow poet Henri Cole, what he was asking, with “anxiety,” in “Exposure” was: “what am I doing striking a few little sparks when what the occasion demands is a comet?”{{16}}[[16]]Cole, “Seamus Heaney: The Art of Poetry No. 75.” The Paris Review 144 (Fall, 1997).[[16]] But those little sparks were still inspired sparks, blown by the “wind” Heaney feels as a “wood-kerne” hidden and camouflaged—like the Irish soldiers Spenser had described in A View of the Present State of Ireland (1596)—by protective bole and bark, the autumnal woods surrounding Glanmore Cottage. To my ear, “these sparks” evoke Shelley’s final petition to that “breath of autumn’s being” in the “Ode to the West Wind”:

Drive my dead thoughts over the universe

Like withered leaves to quicken a new birth!

And, by the incantation of this verse,

Scatter, as from an unextinguished hearth,

Ashes and sparks, my words among mankind!

In the end, Heaney, neither informer nor internee, confirms (though not without misgivings) his decision to become an internal émigré and noncombatant. In moving to Glanmore Cottage, a secluded retreat and place of writing he came to love and eventually to purchase, Heaney committed himself full-time to poetry, recognizing—as had Wordsworth, in an earlier time of political “catastrophe” and with the support of his sister Dorothy—his “true self” as “Poet,” file. In the third of the “Glanmore Sonnets” (in Field Work, 1979), Heaney starts to compare himself and his wife to “William and Dorothy,” only to be interrupted by Marie (OG, 158)—who may, however, have played a role not unlike that of Dorothy. Asked by Helen Vendler about separations and other difficulties, Marie insisted that “all I want is for Seamus to be able to write his poems.” That was what mattered as well to Dorothy, that “belovéd woman” and “companion” who had, in a time of political and emotional turmoil, Wordsworth insisted,

Maintained for me a saving intercourse

With my true self…preserved me still

A Poet, made me seek beneath that name,

And that alone, my office upon earth.{{17}}[[17]]For Marie’s comment, see Vendler, “Seamus Justin Heaney 13 April 1939-30 August 2013” (2014), p. 2. Wordsworth, The Prelude (1850), XI. 340-47. In North, in the sequence “Singing School” (its title taken from Yeats’s “Sailing to Byzantium”), Wordsworth figures as well as Yeats.[[17]]

But “poetry,” as Auden famously insisted in his elegy for Yeats, “makes nothing happen.” Even (OG, 102, 103) lying “down/ in the word-horde” and “jumping in graves” (as Heaney, a self-mocking “Hamlet the Dane” does in the “skull-capped ground” of North) cannot effect political change any more than the imaginative “flames” of Yeats’s “Byzantium” (YP, 298) can “singe a sleeve” in the material world. As Heaney says, echoing Auden and Yeats: though poetry is “unlimited” in its capacity for “pure concentration,” “no lyric has ever stopped a tank.” {{18}}[[18]]Heaney, The Government of the Tongue: Selected Prose 1978-1987 (NY: Farrar, Straus and Giroux, 1989), 107-8. “In one sense, the efficacy of poetry is nil—no lyric has ever stopped a tank. In another sense, it is unlimited.” Though not politically “instrumental,” it functions “as pure concentration.[[18]] Nor, in “Exposure,” can “meagre sparks” outweigh the comet’s million tons of light.

As man and poet, Heaney had to acknowledge the passionate intensity and terrible beauty of that climactic comet’s “pulsing rose.” But there is an implicit caveat in that very image, a reservation taking the form of repetition and rondure. For this final image in the final poem of North—the “comet’s pulsing rose”—not only echoes the absent afterglow of the comet’s tail, imagined resembling the fruit of the rose, the ripe seed-receptacles that remain after the petals have been removed (“Like a glimmer of haws and rose-hips”); it also curves back to “Antaeus,” the opening (post-Dedication) poem in the volume, and to what proved to be the earth-renewed wrestler’s over-confident and punning assertion: “When I die on the ground,/ I rise flushed as a rose.” The internal “rose”-echo is obvious, and I take the oblique allusion to “Antaeus” also to be deliberate, an echo adding to the undermining of the pulsing comet’s combustible political force.

For in the trajectory of North, atavistic Antaeus had been forced to yield. Not, finally, to the strength and spurred light of hubristic Hercules, but to the responsibility-weighing tristia and “second thoughts” of Seamus Heaney, acting in his true office upon earth: that of Poet. A poet may make, as Heaney often has, public statements; but a poet’s resistance to pressure to become overtly “committed” is usually accompanied, as in the case of Wordsworth and Coleridge (disenchanted by the course of the French Revolution), by a belief that the authentic agent of change is not political activism but the creative imagination, with its implicit assertion of the essential autonomy of poetry. This is a claim certain, in a time of troubles, to frustrate readers who want their poets to “engage” rather than fiddle. And yet we find, at the end of “Exposure,” a poet, or file, scattering, not the spent ashes of partisan politics and sectarian hatred, but those vestigial yet undying “sparks”—his inspired words—among us all. Seamus Heaney’s four decades of creativity following North, defending and reaffirming the central value of poetry, have amply vindicated the pivotal decision publicly wrestled over in “Exposure.”

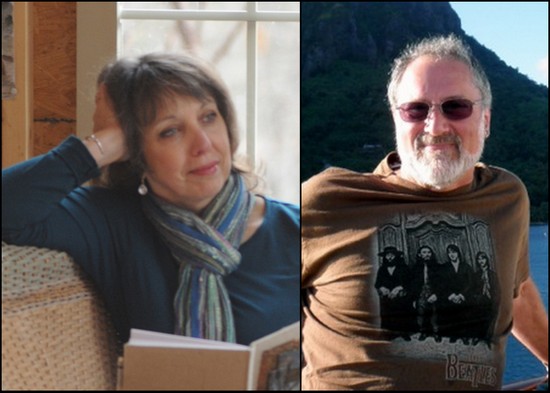

— Patrick J. Keane

Patrick J. Keane is Professor Emeritus of Le Moyne College and Contributing Editor at Numéro Cinq. Though he has written on a wide range of topics, his areas of special interest have been 19th and 20th-century poetry in the Romantic tradition; Irish literature and history; the interactions of literature with philosophic, religious, and political thinking; the impact of Nietzsche on certain 20th century writers; and, most recently, Transatlantic studies, exploring the influence of German Idealist philosophy and British Romanticism on American writers. His books include William Butler Yeats: Contemporary Studies in Literature (1973), A Wild Civility: Interactions in the Poetry and Thought of Robert Graves (1980), Yeats’s Interactions with Tradition (1987), Terrible Beauty: Yeats, Joyce, Ireland and the Myth of the Devouring Female (1988), Coleridge’s Submerged Politics (1994), Emerson, Romanticism, and Intuitive Reason: The Transatlantic “Light of All Our Day” (2003), and Emily Dickinson’s Approving God: Divine Design and the Problem of Suffering (2007).