x

On a Thursday afternoon in September, some three decades ago, I sat in Mr. Belanger’s fifth-grade science class at Tatnuck School when the Blue Angels roared into town. Six insignia-blue jets buzzed the hillsides of gold-orange trees and circled over the city before they threw down their landing gear. It was opening day of the Worcester Air Show, and our sleepy hamlet had suddenly become center stage for a spectacle of aeronautic derring-do and unimaginable pageantry. We stood—two dozen mesmerized kids temporarily released from the rigors of life science—in the windows of that classroom, staring out as the blue planes, one by one, lined up and touched down. Then Mr. Belanger barked at us, and we returned to whatever irrelevant topics awaited in our textbooks.

The ensuing three days of air-show mania were unlike anything I’d ever experienced. The roar of an approaching Skyhawk would send me sprinting outside as if the house were on fire. Blue jets thundered overhead, practicing right above the yellowing sugar maple in my backyard. The ground rumbled as planes climbed, looped, crossed, barrel-rolled and boomed on high, turning the sky above Walter Street into a veritable six-ring circus. My friends and I dashed and chased, waving at the pilots who flew so low we could see their golden helmets and almost read their names painted on canopy sides. Our prosaic lawn furniture became front row seats for an otherworldly show. Delta-winged jets, tucked inches apart, twirled heavenward before screaming back toward Earth. Even now, decades later, the memories of those days seem fantastic and utterly surreal.

When the air show ended, I knew, and declared quite publicly, that one day, I would become a Navy pilot.

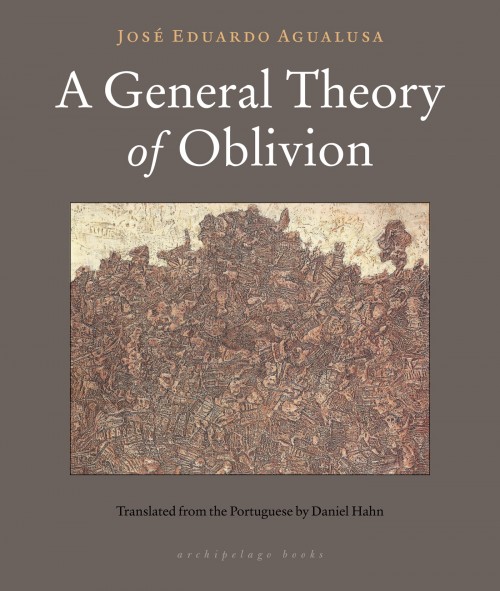

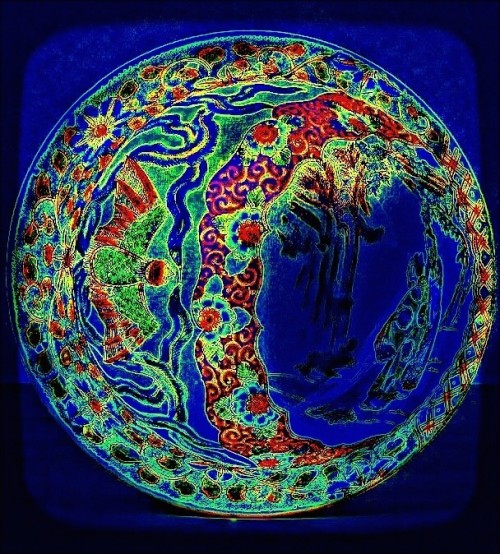

Blue Angels in the A-4 Skyhawk, as the author first saw them

Blue Angels in the A-4 Skyhawk, as the author first saw them

§

Emerson writes that self-trust is the essence of heroism. The human spirit, in conflict with itself, must struggle against the trappings of society, ego, and expectation. The enemy is a prevalent falsehood—the mask that we wear out in the world. To hear the Transcendentalist tell it, the hero removes the mask, revealing some inner light, illuminating a truer wisdom.

I knew all about masks. As a snaggle-toothed boy growing up just forty miles from Emerson’s front door, self-trust came reluctantly, if at all. Instead, I admired men like Chuck Yeager, or at least Tom Wolfe’s re-imagined version of Yeager, fabricated from the author’s imagination and an ancient gallery of heroic archetypes. The enduring myth of American meritocracy offered up a path for a good ole boy from West Virginia to convert passion and courage into an express ride to the very top of the pyramid—a test pilot, a general, a bona fide hero with world records to prove it. If Yeager could do it, I reasoned, then why not me? I only had to find the appropriate mask, wear it with a rigid certainty, and suppress any and all emotion that might reveal hesitancy, doubt, or weakness.

§

Ten years after the Worcester Air Show, still pursuing my dream of becoming a Navy pilot, I returned from physics lab to my room at the United States Naval Academy, only to find that a plebe from 10th Company had climbed out of his fifth-floor window and plunged to the brick walkway below.

His shattered, uniformed body was visible from my window as paramedics rushed in vain to save his life. Ambulances, fire trucks, and police cars had cordoned off the road, but the air was eerily still. I expected sirens, but heard only the chirping of birds, the rustle of a breeze off the Chesapeake. Again, it was September. A warm, clear day sparkled. Spinnakers billowed on the Severn River as sailboats tacked their way out to the hazy bay.

The mask had suddenly fallen away.

A moment later, my roommates came back from class. D.J. unpacked his books while Darren tore a long piece of masking tape off a roll and wrapped it around his fingers—sticky side out— and began to daub the tape against his chest, removing dust and lint, preparing for inspection. Darren would quit the Naval Academy later that year and send letters from Wisconsin regaling us with tales of coeds and frat parties.

“What happened?” he asked.

“Doesn’t look good,” I said. “Kid must’ve jumped.”

Paramedics wrapped a vacuum splint around the man’s leg and positioned a backboard nearby. Several firemen closed around the scene. Their arched backs formed a reverent, almost prayerful circle of yellow coats around the dying midshipman. Extending from the center of that circle were navy-blue uniform trousers, the same scratchy wool-polyester pants I wore that day, except the pants on that brick walkway below me were covered in dark blood.

Blood pooled on the bricks. Blood soaked the paramedics’ gloves. At one point, the rescue workers all lurched back in unison. Blood, from a blown artery, geysered out from the center. I felt my knees buckle.

Then D.J. came up and sat beside me on my desk. Just a few weeks into our sophomore year, we had been roommates only a short while. D.J. was an engineer, serious and taciturn by nature. His silence could be unnerving, because I never knew what he was thinking, but in that strange moment, D.J.’s quiet demeanor felt steadying, like a sea captain in a gale. What good were words?

Then an echolalia of chow calls began from open windows all around Bancroft Hall. Sir, you now have ten minutes until noon-meal formation. The uniform for noon-meal formation is working-uniform-blue-delta.

Chow calls were one of the many tedious rituals plebes were forced to repeat, six times a day, at ten and five minutes before each meal. One thousand plebes, minus one, repeated the rote words in a haunted chorus, a maddening mayday from a symphony of oblivious cuckoo clocks chiming the hour. Only this was no mayday. The unfolding misery below our window would not interrupt the routines.

§

I don’t believe that whatever wisdom a middle-aged man has acquired is any truer than the dreams of a ten-year-old boy or a twenty-year-old midshipman. Passions abound, both in the spring of life and in its autumn. We are filled with hope, doubt, fear, longing, joy, and grief. The boy dreams of taking flight, while the grown man reassembles the broken fragments of the past.

These days, I’m a stay-at-home father, a trailing spouse married to a woman who works long, irregular hours as a Navy obstetrician. While my wife manages laboring patients, I spend my time worrying about car pools, sleepovers, birthday party gifts and baseball practice. My children’s schedules dictate the rhythm of my day, leaving precious little time to worry about their dreams: What paths have they already begun to walk? What shapes their destinies? What masks have they already begun to wear into the world? My son wants to play professional basketball; my daughter wants to ride horses and live on a ranch in Montana.

The heroic cannot be the common, nor the common the heroic, Emerson writes. At times, though, I want only simple happiness and security for my children. I don’t want my son’s body battered by contact sports. I don’t want my daughter’s heart broken. But life and wisdom always come with scars.

§

Rituals at Annapolis were enshrined within a tradition and rigidity that even the most ardent cynic might admire. Each moment of our day creaked with customs, from reveille to taps. We marched, saluted, studied, and trained. We followed honor codes and conduct codes. For four years we scoured our rooms, polished brass belt buckles, folded tee shirts and socks with mathematical precision. We tucked sheets into taut hospital corners as though it were a holy sacrament. We believed in big ideas—in America and freedom and power—and we worshipped those ideas through a steadfast devotion to the most minuscule details. Our faith, like our duty, was absolute and unflinching.

For the entire four years we lived together in Bancroft Hall, the largest dormitory in the world. Bancroft Hall was a home and a prison, a hearth and a hell. The massive building, erected at the turn of the last century in the Beaux Arts style, mixed classical symmetries with rococo flourishes. Cold stone surfaces rose to slate gray mansard roofs, trimmed with oxidized copper flashing. Nautical-themed statuary and maritime bas-relief decorated the corners. The scale of the building imposed on us, a structural symbol of an institutional ethos: the individual submitted to the will of the whole, an idea and ideal manifested in rusticated concrete and polished floor tiles. Neoclassical lines spoke of order. We marched beneath its imposing domes and stood midnight watch in Bancroft’s vast, cavernous hallways, always reminded of history, of fallen alumni and of future sacrifice, our individual existences reduced to fodder. For emphasis, brass cannons guarded the grand front staircase.

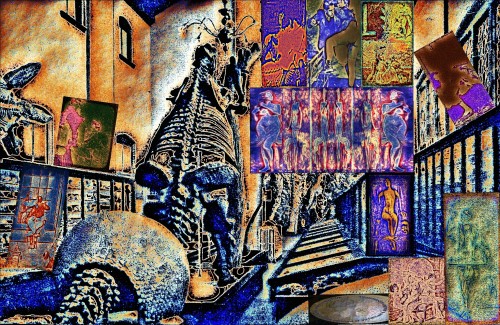

Bancroft Hall, U.S. Naval Academy

Bancroft Hall, U.S. Naval Academy

In Memorial Hall, at the center of Bancroft, were inscribed the names of more than a thousand alumni who died in battle. A flag from Oliver Hazard Perry’s victory at the Battle of Lake Erie in 1812 was enshrined behind glass. That flag reminded each of us daily with its tattered motto: Don’t Give Up the Ship.

Annapolis pushed a hero-heavy curriculum. The ghosts on the yard were all once great warriors, and we were taught to borrow their masks. Tecumseh stood watch over manicured lawns. Every academic building gestured toward mythical grandeur—Nimitz Library, Halsey Field House, Preble Hall. We revered warrior virtues and worshiped at the altar of self-sacrifice and bravery, all the while puffing out our chests with bravado and notions of coming glory. Self-trust received little attention. To interpret the iconography: there was no higher virtue than to lay down your life for your country.

Death, however, came with obligations of community and valor. While it was heroic to die in battle, it was something entirely different to take one’s own life. As the paramedics attempted to hold on to the young man’s fleeting existence on the bricks below my window, our routines continued apace. There would be no time-out for this suicide, no memorial to his sacrifice.

My roommates stepped back from the window and continued getting ready. Darren turned and D.J. taped-off his back. “Cooperate and graduate,” we learned, recited and believed as an article of faith. All for one and one for all. I rolled the tape around my own fingers, uncertain what it all meant, and kept watching out the window.

Memorial Hall, U.S. Naval Academy

Memorial Hall, U.S. Naval Academy

§

In his poem “Musée des Beaux Arts,” W.H. Auden reminds us that there is something rather mundane about the shape of human tragedy. The subjective nature of suffering always leaves room for the rest of the world to carry out the logic of the day. Icarus goes kerflooey while someone else is eating or opening a window or just walking dully along. Auden’s poem addresses the very notions of torment and flight. The poem examines Brueghel’s sixteenth-century oil painting Landscape with the Fall of Icarus, which itself returns to the ancient legend of Daedalus and his eager son. Early versions of this legend can be found carved on Etruscan jugs from the seventh century before Christ. Man has long dreamed of taking flight, even before the discovery of the physics and engineering that made such dreams possible. And for even longer, humanity has managed to ignore tragedy with a blithe nonchalance. Perhaps our indifference is some vestigial hangover of evolution. In the primordial ooze, there would’ve been hardly time to stop and mourn for a fallen comrade while the tiger closed on our heels. Progress lacks easy definitions.

In Brueghel’s painting, an indifferent sea swallows up the ghostly legs of the falling Icarus, while shepherds and sailors go about their day. As Auden says, everything turns away.

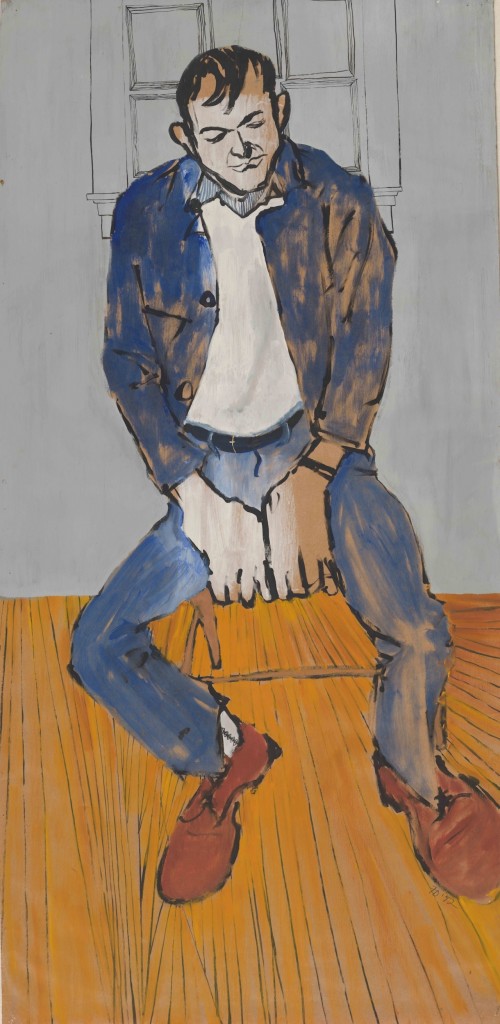

Landscape with the Fall of Icarus by Brueghel, Pieter the Elder

Landscape with the Fall of Icarus by Brueghel, Pieter the Elder

§

Plebe year at Annapolis was the hell of it, ten grueling months stuffed with relentless military indoctrination, hazing, and physical exertion. I saw varsity linebackers reduced to tears, future fighter pilots so frazzled they’d forget their own names. But in that caldron of discipline and cruelty, an incredible thing happened. The self receded. Second-guessing disappeared. The yoking of regulation, discipline, and custom to our daily habits somehow managed to supplant the individual will. Life became a form of ascetic retreat, with a scripted rigidity, uniforms, slogans, and beliefs. As cruel and brutal as it could be, the routines were also incredibly liberating. The mask simply fit.

Ego vanished plebe year, perhaps not into some higher plane of spiritual awakening, but it was gone nonetheless. You submitted to the will of the larger institution. You became invisible, indistinguishable, if only to avoid getting reamed out by any one of the three thousand upperclassmen who outranked you. The regulations, routines, and discipline squeezed every last drop of individuality out of the blood, a dialysis designed to filter out lazy and timid habits from civilian life and replace them with the bellicose faith of military mythology and American altruism. To be certain, it was a herd mentality, but when in the crush and rhythm of the herd, oh what freedom!

The flipside to joining the herd was an obliteration of self-trust. Emerson wouldn’t have lasted a week at Annapolis. To question, to exert, to challenge—these things were unimaginable. Membership exacted the steepest price. Self-trust wasn’t heroic, it was dangerous and defiant, a tumor in the organs of an otherwise baleful gallantry. The very last thing a military force can withstand is the warrior who thinks too much.

The plebe who jumped that bright September day was named Kevin. Though I didn’t know him personally, the odds were good that we’d passed each other in the halls. I might have braced him up, chided him for an untucked shirt, or demanded he address me as “sir.” Until he jumped, he was just one of a nameless legion of young men and women like me, who turned over our identities and fates to the hallowed traditions of Annapolis.

Only later did I learn that Kevin came from Ohio. He’d managed to gut it out through the misery of Plebe Summer, but the end was still a long way off. Kevin wanted to quit the Academy, perhaps to return to a more normal life along the shores of Lake Erie, but his well-meaning family, friends, and company officer all told him to stick it out. So did the institutional codes. The reminders were everywhere: Don’t give up the ship.

I can only imagine how words and ideas raged like cannon fire in Kevin’s mind as he struggled. I’d certainly suffered my share of setbacks and doubts during my own plebe year. Sometimes the pressure just got to be too much.

Did leaving for Kevin feel so much like failure that dying seemed a more reasonable option? Did words like sacrifice, duty, and hero slash at him as he pitted them against other words, like freedom, family, and home? Abstract ideas can inspire men to great sacrifices, or they can bring about catastrophic consequences.

As Kevin’s life spilled out on the brick sidewalk below my window, the only thing I processed was the waste of it all.

§

There’s very little that’s heroic about being a stay-at-home dad. No archetype exists, no books about domesticated heroes have been written. My day-to-day challenges involve time management and festering peccadilloes of unsorted laundry and unfinished homework. “A man is his work,” my father intones, and these days my labor involves making beds, ignoring dust piles beneath the furniture, driving the kids to school. My failures and fuckups register in the emotional damage I can do with a raised voice or forgotten promise. My successes are far more muted. There are no air shows, no bright blue jets and golden helmets. There are no uniforms to hide behind, no masks to wear. A bizarre emphasis falls on the most mundane—the al dente texture of mac ’n’ cheese, the book reports I forget to check until the last minute. I can’t say how high or low the stakes are. Some days this work seems important. Other days, I feel like I’m wasting every second of the precious few I have left.

I never became a Navy pilot, though I came close. I graduated from the Naval Academy, became an officer, and eventually reported to flight school at the very same base where the Blue Angels were stationed. For six months, I donned a helmet, a flight suit, and a parachute and learned how to fly. On yet another September day, I climbed into a T-34 and soloed. After landing and shutting off the engine, I strutted across the flight line like I’d finally arrived at the threshold of where heroes dwelled. But the feeling didn’t linger. In fact, the closer I came to the finish line, the emptier I felt.

I thought that becoming a Navy pilot would change something fundamental about who I was. I thought gold wings would somehow smooth out the rough edges, erase doubts, fill in the empty places. In short, I assumed that I’d grow into the mask. But the opposite was happening. A month or so after that first solo, I suffered a seizure in an airplane. I was lucky to have survived, but I would never again pilot an airplane.

I suppose words like surrender and failure often seem loaded, freighted with the tincture of forever: heroic narratives that offer few examples of second-place finishers. As a young man, words and ideas seemed ironclad, irrevocable, and failure felt freighted with only disgrace. But the moral value of a win-at-all-cost mentality is a very shallow one, not to mention entirely false. When I was forced to stop flying, I assumed my life would never recover. But I grew up. I learned, listened, and saw beyond rigid notions of right and wrong. We all win. We all lose. In somewhat equal proportions.

At ten and at twenty, it was easier to believe in mythical, right-stuff heroism. My ego willingly surrendered to the bon mot and the battle flag. Only later, with failure, with surrender, was I able to begin to understand self-trust. Emerson doesn’t address this, but sometimes self-trust looks a lot like self-doubt.

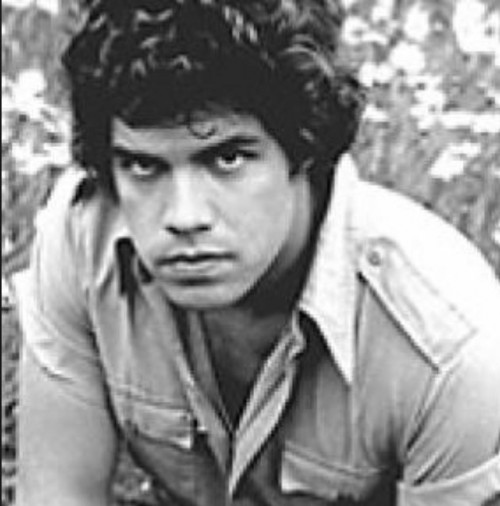

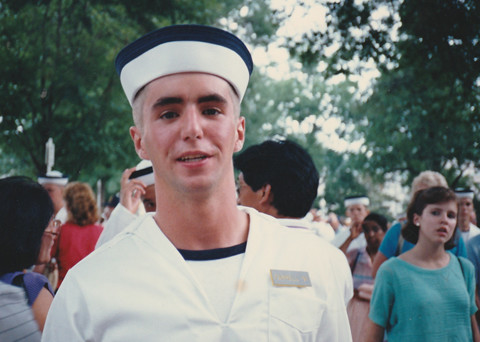

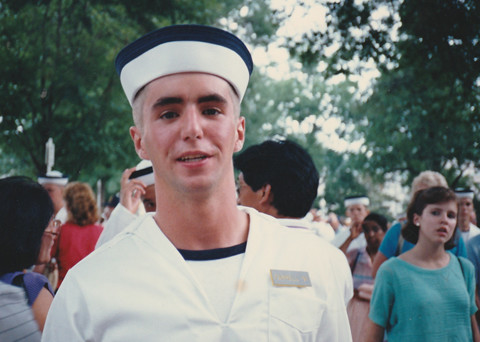

The author in his plebe year

The author in his plebe year

As I boy I read and reread Yeager’s autobiography. I watched The Right Stuff so much that my VCR tape began to stretch. I felt called to the shores of the Severn, but I certainly didn’t understand the implications or repercussions of that calling. My dreams were twisted and warped by the very myths in which I so vehemently believed. Watching the grisly aftermath of a shipmate leaping into the abyss was like watching some inverted, mangled, nightmarish version of my dream.

I wish I could go back and tell Kevin that things would have improved. Plebe year eventually would end. Whatever burdens he carried with him to the ledge that day were temporary ones. Didn’t he know that? I wish I could have convinced him that there was no lasting shame in quitting the Academy. He would have recovered. Like my roommate, Darren, he could have written letters from a civilian college—boasting of frat parties and girlfriends—while his roommates back at Annapolis envied his freedom. Instead, he opened a window on a glorious September day and jumped.

And though my kinship with him was institutional—born of the anonymous Brigade of Midshipmen and the identical uniforms we wore—his short life became an enduring lesson. From my window, I watched him take his final breaths. Something died in my own heart too. Was it innocence? Was it faith?

I would continue to believe in heroes. I would wear my class ring and feel an incredible pride as the Blue Angels roared over graduation. But I would also eventually leave behind the simplistic codes and the consuming urgency of an organization that esteems martyrdom. I would eventually see through the cracks in the ivory tower, smell the rot in the walls.

As Kevin’s life ran out, right there on the brick sidewalk below me, could he have fathomed how the routines around us continued undisturbed? Was he trying to make a statement? Was I the only one who heard? The institution had long before turned deaf. His suicide hardly altered the plan of the day. But I felt the mask slip.

And yet we turned away from Kevin, we who claimed to be his shipmates, trusted guardians of each other’s fate. We didn’t even skip a formation for his death. And for twenty-five years I’ve carried a measure of shame about that. Below my window, his navy-blue uniform pants and black shoes were drenched in blood, while I and four thousand other midshipmen simply prepared for lunch, as if nothing had really happened.

Like the ploughman in Brueghel’s painting and Auden’s poem, I bent to my task. I turned away. There simply wasn’t time to listen. Or maybe there wasn’t enough silence. The voices of shouting plebes droned off into a din as the paramedics lifted Kevin’s lifeless body onto the gurney. Sirens began, drowning out the wind, the birds, my own thoughts and feelings. I did what I had to do. I turned back from the window, straightened my belt buckle, and went out to formation.

Self-trust was a tall order, especially for an idealistic young man who wanted the world to make sense. Heroes carried on, even if carrying on was the least heroic thing any of us did that day.

After the fall, Daedalus surely saw the sky as a burden for the rest of his life. Every cloud, every soaring bird, and every star became another reminder of his lost son. Or maybe that’s just foolishness. Maybe I’m still looking towards myths and heroes to explain the world, rather than trusting my own heart. If self-trust perpetuates heroism, what does that say about self-doubt?

I see not any road of perfect peace which a man can walk, Emerson writes, but to take counsel of his own bosom.

It is morning here, and birds are singing and the light is golden. Soon my kids will come bursting from their dreams, hungry, eager for whatever private desires spur them through the day and fill their beings. I want them to soar, of course, though I’m fearful of what they may encounter in flight. But for now, I will make breakfast and oversee showers. I’ll try not to worry about what kind of people they will become, where life will take them, or how it will twist and turn, with its infinite number of ways to break hearts but also to stir passions. We forge ahead on these fragile, corruptible paths, always capable of discovering great joys but never far from sadness either. But I don’t have time to ponder these things much, because my kids are almost awake, and there is so much to be done.

—Richard Farrell

x

x

Richard Farrell is a graduate of the U.S. Naval Academy and Vermont College of Fine Arts. He is an Associate Editor at Numéro Cinq and the Nonfiction Editor at upstreet. His work, both fiction and non-fiction, has appeared or is forthcoming in Descant, Hunger Mountain, Newfound, Blue Monday, Dig Boston, Contrary, and others. He is currently writing a collection of short stories and a novel. In 2016, he will be a resident writer at the Ragdale Artist Community in Lake Forest, Illinois. He lives with his family in San Diego.

x

x

Cynthia Flood

Cynthia Flood Portrait of Cy Twombly, Fielding Dawson

Portrait of Cy Twombly, Fielding Dawson Richard Jackson & Robert Vivian

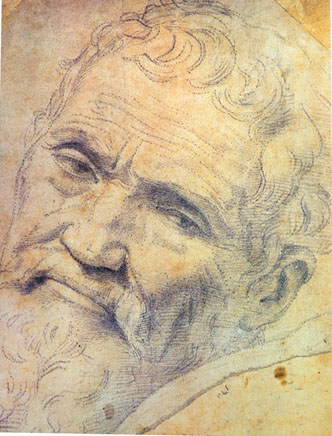

Richard Jackson & Robert Vivian Michelangelo by Daniele da Volterra, 1533

Michelangelo by Daniele da Volterra, 1533