Ludo’s central role—a forgotten and then unnoticed eye in the sky spying on others, later thought of as an invisible goddess—and her predicament as an outlier figure who is part myth, part creature, and part human (something stemming, perhaps, from Agualusa’s love of South American fiction and its magical realism tradition), affords Agualusa distance from what he want to depict. —Jeff Bursey

A General Theory of Oblivion

José Eduardo Agualusa

Trans. Daniel Hahn

Archipelago Books

Paper, 249 pp., $18.00

.

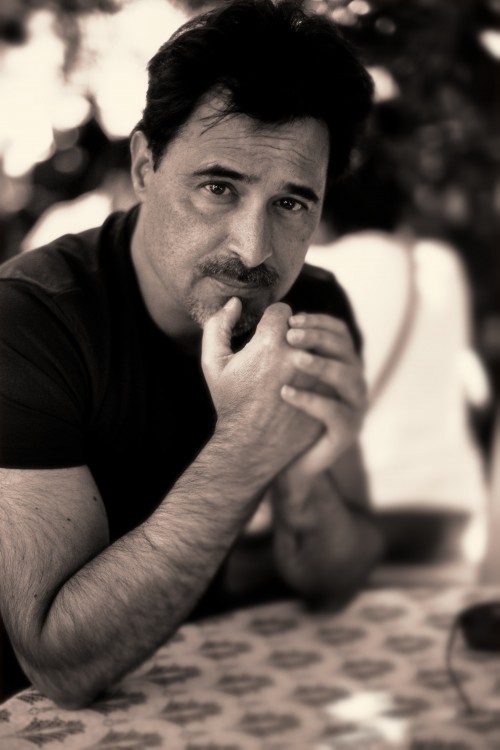

I. José Eduardo Agualusa (b. 1960) often treats the troubled past of his native Angola, a former Portuguese colony, in an ostensibly light manner, the hints of violence, treachery, conflicted identity, and desperation communicating the meanness of life during the War of Independence (1961-1974) and, especially, the civil war that followed (1975-2002).

In his International Foreign Fiction Prize-winning novel The Book of Chameleons (2004, English translation published in 2007) Agualusa mixes the tale of a gecko infused with the spirit of Jorge Luis Borges with the daily life of his owner, Félix Ventura, a man who reinvents the histories of clients eager to cover over their civil war activities. Several characters Ventura has dealings with serve to fill in the picture of a country undergoing an uneasy and fragile transition from hostilities to peace. There is menace in this tightly wrapped story to both main parties, from different sources, and without giving anything away, it can be said that the atmosphere around the amusing or profound thoughts of the Borges gecko act like a lantern held up against a darkness that could swallow everything.

My Father’s Wives (2007, English translation published in 2008) examines racial issues and mediums that people choose to share stories: music, oral history, and literature. Agualusa undercuts their truthfulness (emotional and factitious) by mingling the tales of characters who seem real with those we are told, almost assured, are not. Well before the end of this clever, poignant novel we are becalmed in a sea of lies, half-truths, and possible realities, forced, like those we’re reading about, to adapt to ever-changing conditions. Where we land depends on what we choose to believe. Here, as in The Book of Chameleons, there is a fine degree of control over a debilitating existence lived under almost constant strife and mayhem.

II.

Many of the same themes are present in A General Theory of Oblivion (2013; English translation published in 2015), which is set between the mid-1970s and the early 2000s. (It would be wrong to regard or dismiss the persistence of Agualusa’s themes as obsessive or tiresome sifting and resifting of material. Aleksandr Solzhenitsyn, John Dos Passos, and William Vollmann, along with many more, have rescued important and hidden facts from historical oblivion and worked to keep alive the memory of incidents that plunged entire peoples into despair or periods of ferocious activity, and they have contributed new angles from which to analyze obscure and well-known events. Similarly, Agualusa is mining a rich and deep national memory and has much to tell readers.) The cast recalls those from the previous books: strong women, women praised for their beauty, ignorant men, thick-headed and greedy men, victims of tragedy, and the kind-hearted. Above them all is Ludovica (Ludo) who has accompanied her sister, Odete, and her new brother-in-law, Orlando, from Portugal to Angola just before independence is brought about. She is the figure Agualusa focuses on. Through her, despite her isolation in an apartment building, we are given an overview of Angolan history and society.

Well before leaving for a new life in Africa, Ludo could not stand being outdoors (she “never liked having to face the sky”), which means she is drugged for the flight to Luanda, the Angolan capital. When unrest first breaks out in the city streets, with demonstrations preceding armed warfare, followed by the overthrow of a government, a brief cessation of complete hostilities, and then the decades of factional fighting involving Angolan, Cuban, South African, and other soldiers or insurrectionists, she stays, as she always has, in her missing relatives’ apartment—they attend a party one night and never return—fending off robbers with a pistol before erecting a wall that seals off the apartment entrance from the rest of the building. As conditions throughout the capital and the nation deteriorate and people flee the country, the other tenants vanish until Ludo is, perhaps, the only one remaining. Her company is an albino German shepherd (perhaps a sly allusion to German South-West Africa, an older, colonial name for Namibia, Angola’s southern neighbour) she christens Phantom. She has many books to read and, for a short period, a working telephone, radio, and phonograph. For food she at first relies on a stuffed pantry and crops from seeds Orlando had planted in his terrace. Covered in a cardboard box with eye and armholes to protect her from the sky, she attends to this tiny, life-sustaining garden, catching water from rainfalls when the municipal systems start to fail. But it is often dry, electricity dies, and supplies eventually run out:

The hunger came. For weeks, weeks as long as months, Ludo barely ate. She fed Phantom on a flour porridge. The nights merged into the days. She would wake to find the dog watching over her with a fierce eagerness. She would fall asleep and feel his burning breath. She went to the kitchen to fetch a knife, the one with the longest blade there was, the sharpest one, and took to carrying it around attached to her waist like a sword. She, too, would lean over the animal as he slept. Several times she brought the knife to his throat.

Over the course of the many years spent without other human company that she wishes to contact—for after a while the apartment building attracts new residents—the window is her sole connection with the outside world. It is also a protection against it, and an apparatus to help her eat, for with the appliances long dead Ludo can only cook on sunny days, thanks to Orlando’s magnifying glasses that focus the sun’s heat. When a monkey enters her garden she is ruthless. Eventually the crops she planted assist with her and Phantom’s food needs.

Ludo writes her thoughts down in a series of notebooks, and Agualusa gives us some of those entries, as well as later ones using other surfaces (always presented in italics):

The days slide by as if they were liquid. I have no more notebooks to write in. I have no more pens either. I write on the walls, with pieces of charcoal, brief lines.

I save on food, on water, on fire, and on adjectives.

Further:

I carve out verses

short

as prayers

words are legions

of demons

expelled

I cut adverbs

pronouns

I spare my wrists[1]

Burning furniture, books, and paintings keeps her warm. Her eyesight is going. Life is getting truly desperate, and then a young boy, Sabalu, begins bringing her food, though he starts as a thief entering her apartment through the window while she sleeps and stealing what looks valuable. His own life story changes once they talk. By the time he shows up, well past the halfway mark, we have met others who, while unaware of Ludo, are linked to her and to each other.

Ludo’s central role—a forgotten and then unnoticed eye in the sky spying on others, later thought of as an invisible goddess—and her predicament as an outlier figure who is part myth, part creature, and part human (something stemming, perhaps, from Agualusa’s love of South American fiction and its magical realism tradition), affords Agualusa distance from what he want to depict. Angola’s almost unremittingly traumatic modern history is an immense and complex set of subjects that here is addressed using Ludo’s panoramic view (but a view, as stated, that is decreasing in ability until she has only “peripheral vision”). While her solitary position doesn’t allow her to become involved with anyone but Sabalu, indirectly, through her family and location, she plays a part in the lives of many others as they, in time, come to do in hers. One of the people who, early in the novel, had been after Orlando’s “‘jewels’,” about which Ludo knew nothing at the time, and a Marxist officer he once was in conflict with, meet just outside the apartment on the same day that others, whose lives we have seen in partial ways, also congregate there. Sabalu had broken through the defending wall, with Ludo’s consent. As in a murder mystery—and there are aspects of the detective novel present—the loose threads are tied up, old wounds are given a chance to heal, mysterious sounds explained, a “sea goddess called the Kianda” finally accounted for, and a long-standing absence is revealed at the midway point.

Many of the other characters—Arnaldo Cruz (a sometime political activist turned businessman, more commonly referred to as Little Chief), Magno Moreira Monte (an intelligence officer), Jeremias (a Portuguese soldier), and Daniel Benchimol (a journalist), to name a few—receive time in the narrative for their stories to be fleshed out. Their lives contribute to the seediness and criminality (societal criminality as distinct from crooks) of Angola, as does advocacy journalism, to dovetail with Ludo’s singular story. It’s by design that she is in an equivalent of a Panopticon overlooking a lawless, somewhat formless state where, as Agualusa has shown in earlier novels, no one feels safe, identities and fortunes are fluid, ideologies (Marxism and capitalism) are opportunistic equally, and outside interests (Cold War powers, smaller countries near and far) and factions work to dismember the nation. Splintering the narrative among these assorted characters helps convey their society’s pandemonium and recklessness.

That centre point is also a symbol for something else. Only a boy can break into the apartment, through the window that is Ludo’s eye; that same orphaned boy, who calls Ludo Grandma, breaks down the wall she constructed as a barrier against the world so he and she can emerge. Windows, walls, and doors can be many things, including hymens, and in a metaphorical sense Sebalu and Ludo are reborn when the wall comes down, this time into a changed world, surrounded by those who are not quite family, but close. At the close of the novel what we hear of Ludo’s childhood might make us reconsider what’s gone before, ponder the multiple meanings residing in the imagery, and appreciate the connection of Ludo’s early life to her acceptance of Sabalu.

III.

In addition to what’s been discussed above, there are other significant features about this book: the first concerns the language of the writing itself, the second Angolan history.

As with other books by Agualusa, each translated by Daniel Hahn, there is attention paid to how to phrase characters’ thoughts and on how to squeeze just the right amount from certain conceits. Trapped and cut off from news, Ludo speculates about what is going on, often in language inspired, perhaps, by the many books she has read: “I’m afraid of what’s outside the window, of the air that arrives in bursts, and the noise it brings with it…. I am foreign to everything, like a bird that has fallen into the current of a river.” In order to explain one man’s disappearance another man invents the tale of his being swallowed by the ground, which matches the vanishing of planes and villages. There is a dancing hippo. People are not recognized for who they are: everyone has an opportunity (and a motive) to be new, or at least camouflaged, in this country that’s a work-in-progress. When Ludo has to convert her library into fuel she feels “…as though she was incinerating the whole planet. When she burned Jorge Amado she stopped being able to visit Ilhéus and São Salvador. Burning Ulysses, by Joyce, she had lost Dublin. Getting rid of Three Trapped Tigers, she had incinerated old Havana.” (This reflects Angola’s own hellish environment.) Descriptions of scenery and nature are used sparingly but effectively: “That afternoon they knocked down the fence and crossed to the other side. They found a bit of water. Good pastures. The wind began to blow. The wind carried heavy shadows along with it, as though it were carrying night, in shreds, yanked away from some other, even more distant desert.” Plain speech used by such people as soldiers and Little Chief is as carefully written:

There were guys locked up for diamond trafficking, and others for not having stood to attention during the raising of the flag. Some of the prisoners had been important leaders in the party. They took pride in their friendship with the President.

“Only yesterday the Old Man and I went fishing together,” one of them boasted to Little Chief. “When he finds out what’s happened, he’ll get me out of here and have the morons who did this to me arrested.”

He was shot the following week.

As in The Book of Chameleons and My Father’s Wives, one feels safely guided by Hahn through the multiple voices and tones of this diverse cast.

The second topic arises from Agualusa’s interest in making sure there aren’t any loose ends: Is history over for Angola? What I mean to suggest is not that the history of a nation can be wrapped up once and for all in narratives (there will always be more stories, and then there are the counter-narratives), but that, to my mind, the conclusion of A General Theory of Oblivion unwittingly indicates that events can come to a neat close. Agualusa’s propensity to connect the actions of his characters, and the characters themselves, as attenuated as they might appear, though it functioned well in the earlier novels, comes off here as overtly predetermined. Ludo, for example, has a background that is useful to link her to Sebalu, but since they become family quickly enough as it is, when the narrative provides us with that story it is, by then, unrequired and in any case too familiar. Certain characters glance off each other and are forever paired, and this happens many times, too many when you dwell on the length of time of the action—decades—and the gigantic sprawl of the canvas, thereby provoking a disbelief, and shutting down critical sympathy. Less reliance on clearing up every mystery could have resulted in a more satisfying novel, especially since there is so much that is bloody and messy. The communal and personal histories combine, as they often can, but more disorder and loss—what Ludo described as being swept along by her adopted country in its long state of turmoil—would have removed the feeling that we are reading something that is artistically schematic and contrived to finish in a burst of sentimentality.

Despite that reservation, one that may be chalked up to personal preference, José Eduardo Agualusa’s A General Theory of Oblivion has much to recommend it. This short novel, written with confidence and poise, contains sharply sketched characters, an evolving and engaging main narrative around Ludo, and years of conflict succinctly summarized and easily understandable.

—Jeff Bursey

NC

Jeff Bursey is a literary critic and author of the picaresque novel Mirrors on which dust has fallen (Verbivoracious Press, 2015) and the political satire Verbatim: A Novel (Enfield & Wizenty, 2010), both of which take place in the same fictional Canadian province. His forthcoming book, Centring the Margins: Essays and Reviews (Zero Books, July 2016), is a collection of literary criticism that appeared in American Book Review, Books in Canada, The Review of Contemporary Fiction, The Quarterly Conversation, and The Winnipeg Review, among other places. He’s a Contributing Editor at The Winnipeg Review, an Associate Editor at Lee Thompson’s Galleon, and a Special Correspondent for Numéro Cinq. He makes his home on Prince Edward Island in Canada’s Far East.

- In the acknowledgements Agualusa thanks “the Brazilian poet Christiana Nóvoa, who at my request wrote Ludo’s poems…”↵