1

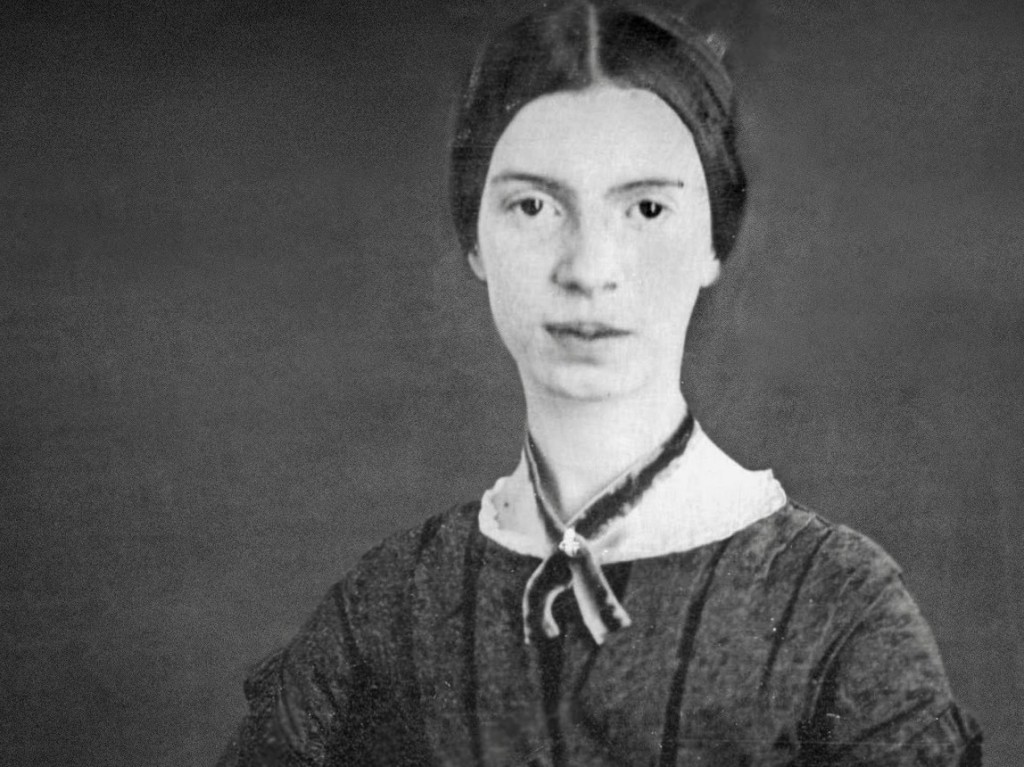

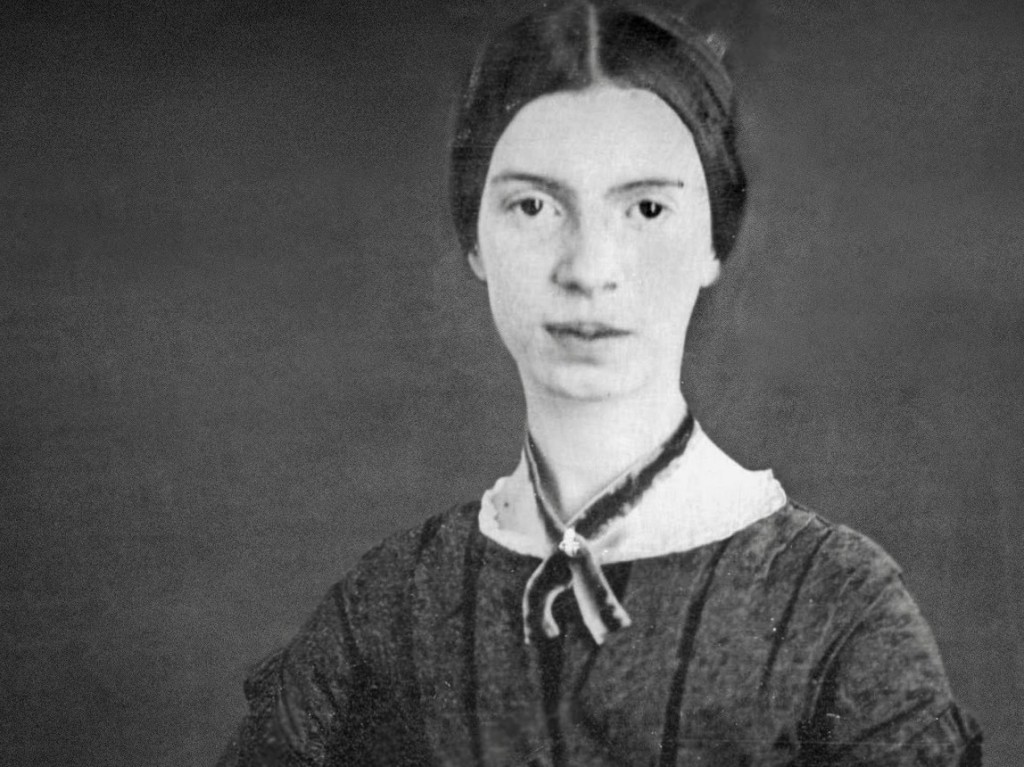

Given the magnitude of her achievement, it is hard to believe that Emily Dickinson’s poetry was not presented in an accurate text until 1955, almost seventy years after her death. And since those poems (almost 1,800 in number) continue to surprise and dazzle us with their linguistic ingenuity and psychological penetration, it is even harder to believe that Emily Dickinson was born 184 years ago!—on December 10, 1830. Famously, she spent much of her later, secluded life in her garden or writing in her room in the family house in Amherst. Yet, on Keatsian “wings of poesy,” she traveled the universe, from the microscopic to the cosmic. Her penchant for privacy far exceeded that of Thoreau, who had augmented Nature, the seminal work of his mentor Emerson, with Walden, the record of a temporary retreat to the woods, to live and write in solitude. Emily Dickinson’s only rivals for creative eminence in later nineteenth-century America were notably expansive: world-famous, globe-trotting Mark Twain, sea-voyaging Herman Melville, and that “kosmos,” Walt Whitman, who spread himself amply, in line-length and in the panorama of his Democratic vistas. In contrast, reclusive Emily Dickinson’s genius was in scrimshaw-like concision, economy, distillation. Yet her reach matched theirs in capaciousness. She took “For Occupation—This—/ The spreading wide my narrow Hands/ To gather Paradise—” (657).

But what did Emily Dickinson think of when she imagined “Heaven” or “Paradise”? More often than not, she clung to Emersonian and Thoreauvian “nature.” Her poems and letters on death and paradise, in which the human and the floral are often conflated by this gardener-poet, provide examples of what Thomas Carlyle, in Sartor Resartus, termed “natural supernaturalism,” a phrase made part of Romantic criticism’s permanent vocabulary with the publication of M. H. Abrams’s landmark study of the secularization of the sacred—Natural Supernaturalism: Tradition and Revolution in Romantic Literature (1971). In an August 1856 letter to her friend Elizabeth Holland, Dickinson’s natural supernaturalism and her pervasive human/floral analogy are explicit, with a fortunate exception: “I’m so glad you are not a blossom, for those in my garden fade, and then ‘a reaper whose name is Death’ has come to get a few to help him make a bouquet for himself.” This follows a passage that assumes the analogy, claiming that this earth would be Paradise enough were it not for frost and that Grim Reaper. This paragraph begins (Dickinson’s letters often combine prose with poetry) in modified ballad meter: “If roses had not faded, and frosts had never come and one had not fallen here and there whom I could not awaken, there were no need of other Heaven than the one below, and if God had been here this summer, and seen the things that I have seen—I guess he would think His Paradise superfluous” (Letters, 329).

The relatively open-minded Christianity of Elizabeth Holland and her husband may have freed Dickinson to confide such thoughts. A few years later, she would put this fusion of Nature and Heaven, of the physical and spiritual senses, into poetry. What we see, hear, and know is Nature: a harmonious Heaven whose simplicity is superior to our supposed wisdom:

“Nature” is what we see—

The Hill—the Afternoon—

Squirrel—Eclipse—the Bumble bee—

Nay—Nature is Heaven—

Nature is what we hear—

The Bobolink—the Sea—

Thunder—the Cricket—

Nay—Nature is Harmony—

Nature is what we know—

Yet have no art to say—

So impotent Our Wisdom is

To her Simplicity. (668)

Dickinson’s Romantic vision of an Earthly Paradise, its minute particulars as cherished as its sublime manifestations and all the more beautiful because it is under the shadow of death, is reminiscent of Wordsworth, before he froze over, and of Dickinson’s beloved Keats, who never froze over. Keats told a religiously conservative friend, Benjamin Bailey, that his own “favorite Speculation” was that “we shall enjoy ourselves here after by having what we called happiness on Earth repeated in a finer tone, and so repeated” (Letters of John Keats, 1:184-86). In one of the most beautiful passages ever written by Emily Brontë, Catherine Earnshaw’s daughter (the second “Cathy” in Wuthering Heights) describes her “most perfect idea of heaven’s happiness.” She would be “rocking” at the heart of the natural world, “in a rustling green tree, with a west wind blowing, and bright, white clouds flitting rapidly above; and not only larks, but throstles, and blackbirds, and linnets, and cuckoos pouring out music on every side,…grass undulating in waves to the breeze; and woods and sounding water, and the whole world awake and wild with joy….I wanted all to sparkle and dance, in a golden jubilee” (Wuthering Heights, Norton Critical Edition, 198-99).

William Wordsworth

William Wordsworth

Such passages explain Dickinson’s reverence of “gigantic Emily Brontë” (Letters, 721), one of whose poems (“Last Lines,” also known as “No Coward Soul Was Mine”), a favorite of Emily Dickinson, was appropriately read at her funeral service. Wonderful as it is, Brontë’s description of a naturalized “heaven” or “paradise”—a world in motion, in which the speaker actively and joyfully engages in her surroundings—is both Keatsian and Wordsworthian. The final gathering (waves, breeze, woods, water, the whole world awake and joyous), especially Cathy’s wanting “all to sparkle and dance, in a golden jubilee,” unmistakably recalls Wordsworth’s (and Dorothy’s) “host of golden daffodils,/ Beside the lake, beneath the trees,/ Fluttering and dancing in the breeze.” Those flowers, which outdo “the sparkling waves in glee,” comprise “a jocund company” in whose presence a “poet could not but be gay,” a joy recalled whenever “They flash upon that inward eye/ Which is the bliss of solitude;/ And then my heart with pleasure fills,/ And dances with the daffodils.” (“I Wandered Lonely as a Cloud”)

Wordsworth’s head-“tossing” flowers are personified in a delicately pagan manner, their “sprightly dance” allying them with sprights or sprites: elfin supernatural beings. That disciple of Wordsworth and mentor to Emily Dickinson, Ralph Waldo Emerson, was also attuned to the sort of earthly paradise that appealed to both Emilys. He began his famous or infamous 1838 Address to the Harvard Divinity School by fusing the “gladsome pagans” in what was his as well as Keats’s favorite Book of Wordsworth’s epic poem, The Excursion (those pagans who “looked” and “were humbly thankful for the good/ Which the warm sun solicited, and earth/ Bestowed” [4:932-38]), with the “pagan” of “The World is Too Much With Us.” Quoting Wordsworth’s sonnet, Emerson shocked his pious audience from the outset by declaring that he, too, would rather be “A pagan suckled in a creed outworn” than a Christian impoverished by being cut off from a vital, fecund nature sacrificed to both an austere religion and a crass materialism of “getting and spending.” Accordingly, he began the Divinity School Address with his own deeply responsive evocation of nature’s vital, sparkling, floral beauty. In “this refulgent summer,” it has been “a luxury to draw the breath of life. The grass grows, the buds burst, the meadow is spotted with fire and gold” (Essays and Lectures, 75). Those meadows were alive with flowers aglow with the light of Wordsworth’s “golden daffodils,” and sharing the pagan vitality of their “sprightly dance.” Emerson, like early Wordsworth, would have concurred with Emily Dickinson’s speculation in the letter to Elizabeth Holland: Had God “seen the things that I have seen” this summer, he would—Dickinson boldly or blasphemously surmised—“think His Paradise superfluous.”

It seems a shame that Emily Dickinson, who knew and admired Emerson’s essays, stayed in her room when, in 1872, the great man, after a lecture at Amherst College, visited her brother and sister-in-law, living just next-door. With his acute eye, Emerson would surely have recognized genius, just as he did when he first laid eyes on Whitman’s then-unpublished poetry. There are many passages in which Emerson, a peculiarly grounded Transcendentalist, evokes an earthly paradise. In his essay on Swedenborg in Representative Men, Emerson claimed that the only thing “certain” about a possible heaven was that it must “tally with what was best in nature.” It “must not be inferior in tone…agreeing with flowers, with tides, and the rising and setting of autumnal stars.” “Melodious poets” will be inspired “when once the penetrating key-note of nature and spirit is sounded,—the earth-beat, sea-beat, heart-beat, which makes the tune to which the sun rolls, and the globule of blood, and the sap of trees.” (Essays and Lectures, 686-87)

Ralph Waldo Emerson

Ralph Waldo Emerson

Like Keats’s “a finer tone”—descriptive both of the unheard music in the “Ode on a Grecian Urn” and of the repetition of earthly happiness “here after”—Emerson’s “not…inferior in tone,” and stress on key-note, melodiousness, and tune, echoes a text familiar to both Keats and Emerson: Wordsworth’s Excursion, and the Solitary’s reference in Book 2 to “Music in a finer tone” (2:710). Even later Wordsworth, tamed-down and religiously orthodox, never ceased to be a lover “of all that we behold/ From this green earth” (“Tintern Abbey,” lines 104-5), a poet who found his “Paradise, and groves/ Elysian”—provided the human intellect was “wedded to this goodly universe/ In love and holy passion”—to be a “simple produce of the common day” (“Prospectus” to The Recluse,” lines 43-55). Even in revising from a more conservative perspective his account of his early enthusiasm for the French Revolution, Wordsworth never recanted the desire initially expressed, to exercise his skill, “Not in Utopia” or some other ideal place, “Heaven knows where!/ But in the very world, which is the world/ Of all of us,—the place where, in the end,/ We find our happiness, or not at all!” (The Prelude [1850 version]), 11:140-44).

“Oh Matchless Earth,” Emily Dickinson exclaimed in a one-sentence letter, “We underrate the chance to dwell in Thee” (Letters, 478). She was borrowing from the “Prologue” to Wordsworth’s Peter Bell. Having sailed into the heavens in his little boat in the shape of a crescent moon, and having described the constellations and planets, the speaker asks rhetorically, “What are they to that tiny grain,/ That little Earth of ours?” And so he descends: “Then back to Earth, the dear green Earth…See! There she is, the matchless Earth!” (Peter Bell, lines 49-56). Dickinson herself might be “glad” that others believed they were, in the opening exclamation of her early poem, “Going to Heaven!” But, for herself,

I’m glad I don’t believe it

For it would stop my breath—

And I’d like to look a little more

At such a curious Earth! (79)

There is yet another parallel to Emily Dickinson’s thought that “Nature is Heaven,” or that Heaven would be superfluous, if only our earthly Paradise were free of frost and death. In a passage familiar to Wordsworth, Keats, Emerson, and Dickinson, Milton’s archangel Raphael offers a speculative analogy. Explaining to Adam the mysteries of celestial warfare by likening spiritual to corporeal forms, he adds: “Though what if Earth/ Be but the shadow of Heaven, and things therein/ Each to the other like, more than on earth is thought?” (Paradise Lost 5:573-76). Emily Dickinson echoed and altered this passage in an 1852 letter to “Dear Susie” (her soon-to-be sister-in-law, Susan Gilbert). Reversing Raphael’s “therein,” Dickinson locates love “Herein,” and concludes by taking literally the angel’s rhetorical but intriguing question: “But that was Heaven—this is but Earth, Earth so like to heaven that I would hesitate should the true one call away.” (Letters, 195; italics in original). Milton himself may have been open to the idea of Heaven as a projection of earthly happiness complete with a terrestrial landscape. In his fusion of the Classical and Christian in “Lycidas,” the pastoral elegist leaves us free to imagine the risen man as either “saint” in Heaven or as the “genius of the shore,” drowned, but now, through the power “of him that walked the waves,” mounted to a place “Where other groves and other streams along,/ With nectar pure his oozy locks he laves” (lines 172-75).

In a jocoserious, life-affirming poem looking back to Romantic and Emersonian “nature worship” and ahead to the earth-centered female persona of Wallace Steven’s “Sunday Morning,” Dickinson rejects religious ritual, a formal “church,” and an other-worldly Heaven in favor of an earthly paradise, a God immanent rather than transcendent, and salvation as a daily process rather than a static end-state:

Some keep the Sabbath going to Church—

I keep it, staying at Home—

With a Bobolink for a Chorister—

And an Orchard for a Dome—

Some keep the Sabbath in Surplice—

I just wear my Wings—

And instead of rolling the Bell, for Church,

Our little Sexton—sings.

God preaches, a noted Clergyman—

And the sermon is never long,

So instead of getting to Heaven, at last—

I’m going, all along. (324)

In an 1863 letter to Thomas Wentworth Higginson, in which she describes herself as “not reared to prayer,” Dickinson pronounces “the ‘Supernatural’…only the Natural, disclosed” (Letters, 423-24). In a poem written that year or the year before (Johnson dates it 1862, Franklin 1863), dawn and noon seem symbols of what she calls “Heaven.” The skepticism implicit in the setting of “Heaven” in quotation marks is confirmed in the final two stanzas:

The Rapture of a finished Day—

Returning to the West—

All these—remind us of the place

That Men call “Paradise”—

Itself be fairer—we suppose—

But how Ourself, shall be

Adorned, for a Superior Grace—

Not yet, our eyes can see— (575)

In two letters of 1873, Dickinson subverts Paul’s text (“For this corruptible must put on incorruption, and this mortal must put on immortality”) about the dead being raised and changed as a consequence of Christ’s Resurrection (1 Cor. 15:52-53). In the first letter (April 1873), she pronounces the novelist George Eliot (whom she knew to be a woman, Marian Evans) a “mortal” who “has already put on immortality,” adding that “the mysteries of human nature surpass the ‘mysteries of redemption,’ for the infinite we only suppose, while we see the finite” (Letters, 506). Later that year, in a letter to Elizabeth Holland, Emily notes that her sister Lavinia, just back from a visit to the Hollands, had said her hosts “dwell in paradise.” Emily declares: “I have never believed the latter to be a supernatural site”; instead, “Eden, always eligible,” is present in the intimacy of “Meadows” and the noonday “Sun.” If, as Blake said, “Everything that lives is holy,” it is a this-worldly truth of which believers like her sister and father are cheated: “While the Clergyman tells Father and Vinnie that ‘this Corruptible shall put on Incorruption’—it has already done so and they go defrauded” (Letters, 508). In a notably legalistic affirmation of earth, included in an 1877 letter to a lawyer, her increasingly skeptical brother Austin, she goes even further:

The Fact that Earth is Heaven—

Whether Heaven is Heaven or not

If not an Affidavit

Of that specific Spot

Not only must confirm us

That it is not for us

But that it would affront us

To dwell in such a place— (1408)

Wallace Stevens, who, in “Sunday Morning,” imagines his female persona asking if she shall not “find in comforts of the sun,” in any “balm or beauty of the earth/ Things to be cherished like the thought of heaven?” insists elsewhere that “poetry/ Exceeding music must take the place/ Of empty heaven and its hymns” (“The Man with the Blue Guitar,” section 5); that we must live in “a physical world,” the very air “swarming” with the “metaphysical changes that occur,/ Merely in living as and where we live” (“Esthetique du Mal,” section 15). Stevens seems to be recalling Wordsworth’s “Prospectus” and Emerson’s seminal book Nature, along with that ardent disciple of Emerson, Friedrich Nietzsche. He might as well have been thinking of Emily Dickinson, and her audacious, even blasphemous preference for the tangible things of this earth, to be cherished above thoughts of an otherworldly Heaven, an abstract place offensive to our nature. Nietzsche’s Zarathustra’s beseeches us in his Prologue to “remain faithful to the earth, and do not believe those who speak…of otherworldly hopes!” She never accepted the Nietzschean premise, the Death of God, but, when she was only fifteen, Emily confided in her friend Abiah Root that the main reason she was “continually putting off becoming a Christian,” despite the “aching void in my heart,” was her inability to conceive of an existence beyond this earth as anything but horrible: “Does not Eternity appear dreadful to you?….it seems so dark to me that I almost wish there was no Eternity.” Two years later she tells a friend that, while she regrets that she did not seize a past opportunity to “give up and become a Christian,” she won’t: “it is hard for me to give up the world” (Letters, 27-28, 67). She is not referring to that material “world” of getting and spending that is “too much with us,” but to this “matchless Earth” indistinguishable from, and perhaps preferable to, Heaven.

2

The problem, of course, is that this Earth, however “matchless,” is not free of frost and death, so often almost indistinguishable in Dickinson. The invasive force in her Earthly Paradise was less the worm than the frost. The link between the fading and freezing-by-frost of her flowers on the one hand, and the death of those she cannot waken on the other, becomes a dominant motif. Her cherishing of a Heaven-like Earth is sometimes connected with the pain inflicted from above. In one poem, while noting the “firmest proof” of “Heaven above,” she significantly adds that, “Except for its marauding Hand/ It had been heaven below” (1205; my italics). In another letter to Elizabeth Holland and her husband, Heaven’s “marauding Hand” seems both a grim Reaper and a cruel Leveler. Writing during a period (autumn, 1858) when an epidemic of typhoid fever had struck Amherst, she cries out, not in concluding but in opening the letter: “Good-night! I can’t stay any longer in a world of death. Austin [her brother] is ill of fever. I buried my garden last week—our man, Dick, lost a little girl through scarlet fever….Ah! Democratic Death! Grasping the proudest zinnia from my purple garden,—then deep to his bosom calling the serf’s child” (Letters, 341).

Virginia Woolf

Virginia Woolf

This letter has become controversial. The admittedly jarring reference to the “serf’s child,” both “politically” and historically incorrect, has been described as insensitive, shocking, an indication of casual snobbishness at best and class-conscious callousness at worst, compounded by (in the phrase of Albert Habegger) her “equating ‘the serf’s child’ with her frost-killed flowers” (My Wars Are Laid Away in Books: The Life of Emily Dickinson [2001], 363). We may be reminded of Virginia Woolf’s Clarissa Dalloway, who imagines people saying of her, “she cared much more for her roses than for” such human but distant “victims of cruelty and injustice” as those who perished in the Armenian genocide (Mrs. Dalloway [Norton Critical Edition], 88). But the best response to the attack on Dickinson’s “callousness” in this letter seems to me that of Judith Farr. After acknowledging the “insensitivity it projects,” she reminds us that “Austin’s [serious] illness and the coming of winter are also equated” in the letter. She then makes her central point, one I would emphasize as well:

To begin with, it is simply the case that Emily Dickinson loved flowers quite as much and as if they were human; her implicit comparison was…not intended to diminish the “little girl,” as she is rather tenderly called….With the cadences of Ecclesiastes and the Elizabethans always vivid in her ear, it was only natural that Dickinson should express the communion and equality of all living forms in death. Indeed, her letter’s zinnia and child commingling in Death’s grasp calls up such lines as Cymbeline’s “Golden Lads, and Girles all must,/ As Chimney-sweepers come to dust.”….Not snobbery, but the power of the aesthetic impulse to which she was subject is chiefly manifested in Dickinson’s much-discussed letter. (The Gardens of Emily Dickinson [2004], 56)

I would add only that Dickinson’s equation, not limited to the influence of Ecclesiastes and Shakespeare, also had Romantic auspices. Between Death’s “grasp” on a proud flower in her royally purple garden and the death of the little child of a servant there is no more gap than we find in “Threnody,” Emerson’s elegy for his little boy, Waldo. Also a victim of scarlet fever, dead at the age of five, that “hyacinthine boy” and “budding man” was never to blossom, though his father prepares for him, in the conclusion of the elegy, an appropriate Heaven: not “adamant… stark and cold,” but a rather Wordsworthian or Keatsian “nest of bending reeds,/ Flowering grass and scented weeds” (“Threnody,” lines 15, 26, 272-75). In a less-discussed but similar letter to Elizabeth Holland, whose child had suffered a crippling injury, Dickinson notes that “to assault so minute a creature seems to me malign, unworthy of Nature—but the frost is no respecter of persons.” In other letters, starting in the 1850s, Dickinson assumes this floral/frost/human analogue, making explicit what is implicit in poems like “Apparently with no surprise,” where “the Frost beheads” the “happy Flower” (1624): namely, her pervasive connection of flowers and frost with human life and death. At times at least, she includes a vision of transcendence for believers, the hope of spiritual resurrection.

Even when “the frost has been severe,” killing off flowers and plants that try in vain “to shield them from the chilly north-east wind,” there can be an imperishable garden. I am quoting from a touching letter of October 1851, anticipating the arrival of Austin. She had “tried to delay the frosts,” detaining the “fading flowers” until he came. But the flowers, like the poor “bewildered” flies trying to warm themselves in the kitchen, “do not understand that there are no summer mornings remaining to them and to me.” But no matter the effect on her flowers and plants of the severe frost brought by the “chilly north-east wind,” she can offer her brother “another” garden impervious to frost. The theme kindles her prose into poetry, minus the line-breaks (in fact, Johnson prints it as a poem, #2). She offers a bright, ever-green garden, “where not a frost has been, in its unfading flowers I hear the bright bee hum; prithee, my Brother, into my garden come!” (Letters, 149). As Judith Farr remarks, such a garden—which “could never exist, except in metaphor”—is “the garden of herself: her imagination, her love, each of which, she says, will outlast time.” As much as any poem in her canon, this early letter-poem, probably written when Dickinson was twenty-one, “discloses the rapt identification she made between herself, her creativity, and her flowers….‘Here is a brighter garden’ instinctively focuses on the garden of her mind, with its loving thoughts that transcend the ‘frost’ of death.” (The Gardens of Emily Dickinson, 56)

A third of a century later, we have a remarkably similar letter in which, at least for her beloved brother, there is an autumnal harbinger of a spiritual as well as a natural spring to come. In this late letter of autumn 1884, the same year she wrote “Apparently with no surprise,” she tells a family friend, Maria Whitney:

…………...Changelessness is Nature’s change. The plants went into camp last night, their tender

armor insufficient for the crafty nights.

……………That is one of the parting acts of the year, and has an emerald pathos—and Austin

hangs bouquets of corn in the piazza’s ceiling, also an omen, for Austin believes.

……………The golden bowl breaks soundlessly, but it will not be whole again till another year.

………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………(Letters, 848)

Anthropomorphizing (as in the 1851 letter, where the flowers try to “shield them[selves]” from the autumn wind), she presents the “tender armor” of her flowers as inadequate to protect them against the autumnal frost. So, alert to their needs, she brings them indoors, into the “camp” of her conservatory. She ends by quoting the admonition from Ecclesiastes, that we are to remember God before the body disintegrates, before “the silver cord be loosed or the golden bowl be broken” (12:6). But Emily differentiates herself from her brother Austin, a closet skeptic who, for the purposes of this letter, “believes”—has faith, that is, not only in the seasonal rebirth of corn from seeds, but in the spiritual resurrection of the body. His sister, adhering to a seasonal form of natural supernaturalism, confines her hope to a natural spring; her “golden bowl” will “not be whole again till another year.”

Two of Emily Dickinson’s most beautiful, and most Keatsian, poems, mark her major seasonal transition, from summer to autumn. In “As imperceptibly as Grief,” summer has “lapsed away,” a beloved season that can’t quite be accused of “Perfidy” since she was always a “Guest, that would be gone.” The poem ends with summer, like Keats’s nightingale, having “made her light escape/ Into the Beautiful,” a Platonic realm beyond us, leaving behind only the memory, which is to be cherished here on earth (1540). In “Further in Summer than the Birds,” which has been described, by Charles R. Anderson, as “her finest poem on the theme of the year going down to death and the relation of this to a belief in immortality” (Emily Dickinson’s Poetry: Stairway to Surprise [1966],169), Dickinson employs liturgical language to commemorate, as in Keats’s “To Autumn,” the insects’ dirge for the dying year. “Pathetic from the Grass,” that “minor Nation celebrates/ Its unobtrusive Mass,” their barely noticeable requiem nevertheless “Enlarging Loneliness.” The music of the crickets, coming later in the summer than the song of birds, is a “spectral Canticle.” Their hymn typifies—in the transition from summer to autumn, with “August burning low”—the winter sleep to come, a “Repose” perhaps implying eternal rest on another level.

In the final stanza, Christian and Hebraic vocabulary yields to pagan. At this moment of seasonal transition, there is, “as yet,” no “Furrow on the Glow” of sunlit, burning August, “Yet a Druidic difference/ Enhances Nature now” (1068). That final religious image, whether we take the Druidic reference as stressing primarily the sacrificial or the animistic element in Celtic nature-worship, powerfully reinforces Dickinson’s own reverence for Nature, its beauty enriched and intensified less, perhaps, by what Anderson calls a “belief in immortality” than—again, as in the ode “To Autumn”—by time’s evanescence and the pathos of mutability, the deeply moving contrast between seasonal return and human transience. That transience extends to all animal life. This poem, written in late 1865 or early 1866, was enclosed in a laconic January 1866 note to her epistolary semi-mentor, Thomas Wentworth Higginson, with whom she had not corresponded for eighteen months. Referring to her beloved dog and constant companion, Emily Dickinson restricted herself to a single statement, and a wry question, less pleading than ironic, perhaps bitter: “Carlo died….Would you instruct me now?” (Letters, 449).

Samuel Bowles

Samuel Bowles

Though of course haunted by the thought of immortality, Dickinson was also dubious. In an 1858 letter to Samuel Bowles, she adopts an ironic, pretension-mocking tone. Distinguishing between nature and “us,” she at once anticipates and deflates modern “species chauvinism,” wondering, tongue-in-cheek, how it is that we mere humans, described by her pastor as a “worm,” should also be the very species singled out for a majestic and special end: a resurrection allegedly obviating any need for mourning, including mourning the death of what would seem to be paradise enough for us: summer with its cherished fields, its bumblebees and birds:

Summer stopped since you were here. Nobody noticed her—that is, no men and women. Doubtless, the fields are rent by petite anguish, and “mourners go about” [Ecclesiastes 12:5] the Woods. But this is not for us. Business enough indeed, our stately Resurrection! A special Courtesy, I judge, from what the Clergy say! To the “natural man,” Bumblebees would seem an improvement, and a spicing of Birds, but far be it from me, to impugn such majestic tastes! Our pastor says we are a “Worm.” How is that reconciled? “Vain, sinful Worm” is possibly of another species. (Letters, 338-39)

By this time, the 1730s’ thunderings of Jonathan Edwards against the moral ills of New England’s sinners in the hands of an angry God had lost some of their resonance, even in Calvinist Amherst. But in his debasement of man as a “worm,” Dickinson’s pastor may (the trope is hardly restricted to Edwards) have been echoing the great Puritan’s description of man as “a vile insect,” a “little, wretched, despicable creature; a worm, a mere nothing, and less than nothing” (The Justice of God in the Damnation of Sinners [1634]). Edwards himself—whose “Martial Hand” of “Conscience” Dickinson presents threatening “wincing” sinners with hellfire, the “Phosphorus of God” (1598)—was echoing Bildad, the second of Job’s false comforters. From the outset, he had advised the innocent sufferer to abase himself. In his final discourse (Job 25:2-6), Bildad wonders if it is even possible for man to “be righteous before God.” To this fear-instilling God of “dominion,” even the moon and stars are unclean; “how much less man, that is a worm? and the son of man, which is a worm!” How indeed, as Emily sardonically inquires, is that abject status reconcilable with our potential for “stately resurrection”?

Man’s biblical genesis and Fall seemed to put that glorious end in doubt. Prior to ejecting guilty Adam and Eve from Eden, the “Lord God” tells them, “dust thou art, and unto dust shalt thou return” (Gen 3:19). For Hamlet, man is “the paragon of animals.., how like a god,” and yet, to him, “what is this quintessence of dust?” (2.2.305-7); Wordsworth, in the opening book of The Prelude, tries to “reconcile” the contradiction: “Dust as we are, the immortal Spirit grows/ Like harmony in music” (1:340-41). Dickinson can engage this tension in the grand tradition, observing that “Death is a Dialogue between/ The Spirit and the Dust,” with Spirit triumphant, “Just laying off for evidence/ An Overcoat of Clay” (976). But she takes a different tack in a couplet-poem she opens by ironically addressing God as “Heavenly Father”:

“Heavenly Father”—take to thee

The supreme iniquity

Fashioned by thy candid Hand

In a moment contraband—

Though to trust us—seem to us

More respectful—“We are Dust”—

We apologize to thee

For thine own Duplicity—(1461)

So much for Bildad-like groveling! Like the image of the worm, that of dust reflects the Calvinist estimate of human worthlessness. But here the “worm” turns, with the “sinful” creature finding fault with the Creator. Despite his seeming straightforwardness, God committed a dubious act (an inconsistency emphasized by the alliterated candid and contraband). In fashioning us as he did, he set up, between dust and immortal spirit, not so much a creative tension as a radical contradiction. He thus stands accused of double-dealing, and any “apology” we make to so duplicitous a God will be less an acknowledgement of our own guilt, or a seeking of pardon, than a self-justifying defense—an apologia in the form of j’accuse directed against a divine adversary. That vindictive God himself supplied the right word. “For I the Lord thy God am a jealous God, visiting the iniquity of the fathers upon the children” (Exodus 20:5). Dickinson, who, like Mark Twain, cherishes the role of lawyer for the plaintiff when it comes to amassing evidence against God’s supposedly benign providence, has the children of Dust visit the charge of injustice upon an anything-but-paternal Heavenly Father, accusing him—blasphemously, though appropriately, given his supreme power—of “the supreme iniquity.”

If this reading is accurate, our apology to God for his “own Duplicity” allies the poem with the most blasphemous of Omar Khayyám’s quatrains addressed to God, at least as adapted by Edward Fitzgerald in a translation the Victorian world accepted with a shock of recognition:

Oh Thou, who Man of baser Earth didst make,

And ev’n with Paradise devise the Snake:

……….For all the sin wherewith the face of Man

Is blackened—Man’s forgiveness give—and take!

The work of such writers as Carlyle, Tennyson and Arnold, and, later, Hardy and Housman, all responding in their different ways to Darwinian and other scientific and rationalist challenges to religious belief (including Biblical Higher Criticism) places an imprimatur on the judgment that Fitzgerald’s version of the Rubáiyát “reads like the latest and freshest expression of the perplexity and of the doubt of the generation to which we ourselves belong.” That acute observation was made, however, not by a British Victorian but by an American—the scholar and man of letters Charles Eliot Norton, writing in 1869, a decade before Dickinson wrote “‘Heavenly Father’—take to thee.” Not only the “doubt,” but the “perplexity” as well, is reflected in Dickinson’s poem, for the syntax of her opening lines suggests petition even more than protest. James McIntosh (Nimble Believing: Dickinson and the Unknown [2004]), identifying “humankind” as “the supreme iniquity,” takes these lines to mean: “Father, take humans, who are the supreme iniquity, to thee” (47). Perhaps; but what, then, of the poem’s final lines? My own reading is closer to that of Magdalena Zapedowska, in her 2006 American Transcendentalist Quarterly essay, “Wrestling with Silence.” She argues that, in this poem, Dickinson focuses, not on the Fall as original sin,

but on the subsequent expulsion from Paradise, which she blasphemously construes as the original wrong done to humankind by a God who first offered people happiness, then distrustfully put them to the test, and finally doomed them to suffering. Undermining the dogma of God’s benevolence, Dickinson contemplates the terrifying possibility that the metaphysical order is different from Calvinist teaching and that the human individual is left wholly to him/herself, unable to rely on the hostile Deity against the chaos of the universe. (“Wrestling with Silence,” 385)

At such moments, Emily Dickinson sounds like her considerably more public contemporary, Mark Twain, who made no secret of his religious skepticism, but who nevertheless refrained from publishing his most vitriolic attacks on the Judeo-Christian God, a divinity he described, even before his dark final decade, as both duplicitous and cruel. As the examples of Emily Dickinson and Mark Twain illustrate, for all our immortal longings, we are haunted, and angered, by the death implicit in our originating dust—in the case of both Dickinson and Twain, what Byron called “fiery dust.” And if the “Heavenly Father” who presides over this beautiful but doomed world really is an indifferent and “Approving God” (1624), Emily Dickinson seems to care less for him and for a posthumous, perhaps empty Heaven, than for this Earthly Paradise—the perishable beauty that must die, everything she wishes could “transcend the ‘frost’ of death,” but which she strongly suspects will not.

“Man is in love and loves what vanishes,/ What more is there to say?” That haunting question was posed by W. B. Yeats in one of his greatest poems, “Nineteen Hundred and Nineteen.” He was not suggesting anything so trite as that we love things and then they disappear. He was reminding us that we love beautiful transient things because they are mutable, doomed to vanish. That is precisely why we cherish them so, recognizing, as Wordsworth poignantly acknowledged even in the great Ode in which he claimed intimations of immortality, that “nothing can bring back the hour/ Of splendor in the grass, of glory in the flower.” These splendors and glories are part of a “supernaturalism” that is “natural.” That great enemy of otherworldly hopes and cherisher of the earth, Nietzsche, referred in a December 1885 letter to irretrievable beauty. In a floral image that would have appealed to Emily Dickinson, who would die shortly after this letter was written, he spoke of Rosengeruch des Unwiederbringlichen: the faint rose-breath of what can never be brought back.

Of course, with Wordsworth, Keats, and Emerson as her precursors, we do not really need Emerson’s disciple Nietzsche and Nietzsche’s disciple Yeats to explain why Emily Dickinson’s Earthly Paradise is not only beautiful but death-haunted. I quote Yeats and Nietzsche (and Emily would, I think, approve) for the poignant beauty of their language in commemorating the pathos of mutability, what Wordsworth—deeply moved by the humblest “flower” that blossoms and blows in the breeze—called, in the final line of the Intimations Ode, “Thoughts that do often lie too deep for tears.”

— Patrick J. Keane

Author’s Note: Though most Dickinson scholars prefer the three-volume edition of R. W. Franklin (Harvard U.P., 1998), Emily Dickinson’s poems are here cited by number from the one-volume Complete Poems of Emily Dickinson, ed. Thomas H. Johnson (Little, Brown, 1957, and often reprinted). Her letters are cited from the three-volume but continuously-paginated The Letters of Emily Dickinson, ed. Thomas H. Johnson and Theodora Ward (Harvard University Press, 1958). Wordsworth, Keats, and Emerson, are cited from: Wordsworth: The Poems, ed. John O. Hayden, 2 vols. (Yale UP, 1981); The Letters of John Keats, ed. Hyder E. Rollins, 2 vols. (Harvard UP, 1958); Emerson: Essays and Lectures, ed. Joel Porte (Library of America, 1983).

.

Patrick J. Keane is Professor Emeritus of Le Moyne College and a Contributing Editor at Numéro Cinq. Though he has written on a wide range of topics, his areas of special interest have been 19th and 20th-century poetry in the Romantic tradition; Irish literature and history; the interactions of literature with philosophic, religious, and political thinking; the impact of Nietzsche on certain 20th century writers; and, most recently, Transatlantic studies, exploring the influence of German Idealist philosophy and British Romanticism on American writers. His books include William Butler Yeats: Contemporary Studies in Literature (1973), A Wild Civility: Interactions in the Poetry and Thought of Robert Graves(1980), Yeats’s Interactions with Tradition (1987), Terrible Beauty: Yeats, Joyce, Ireland and the Myth of the Devouring Female (1988), Coleridge’s Submerged Politics (1994), Emerson, Romanticism, and Intuitive Reason: The Transatlantic “Light of All Our Day” (2003), and Emily Dickinson’s Approving God: Divine Design and the Problem of Suffering (2007).

s

18 (2012)

18 (2012) blow up, the yellow house (2014)

blow up, the yellow house (2014) Levitation (2014)

Levitation (2014) Wolves Evolve (2014)

Wolves Evolve (2014) Apocalypse Now (2012)

Apocalypse Now (2012) Ghost Brides (2012)

Ghost Brides (2012) Merry Christmas (2013)

Merry Christmas (2013) On Sale! (2012)

On Sale! (2012) Willingly (2014)

Willingly (2014) Red Carpet (2012)

Red Carpet (2012)

Lise Gaston. Photo by Josh Davidson.

Lise Gaston. Photo by Josh Davidson.

William Wordsworth

William Wordsworth

Ralph Waldo Emerson

Ralph Waldo Emerson

Samuel Bowles

Samuel Bowles

Shambhavi Roy

Shambhavi Roy

Translator David Need

Translator David Need

Photo by Fred Filkorn

Photo by Fred Filkorn

Chaulky White is the pen name given to the combined effort of

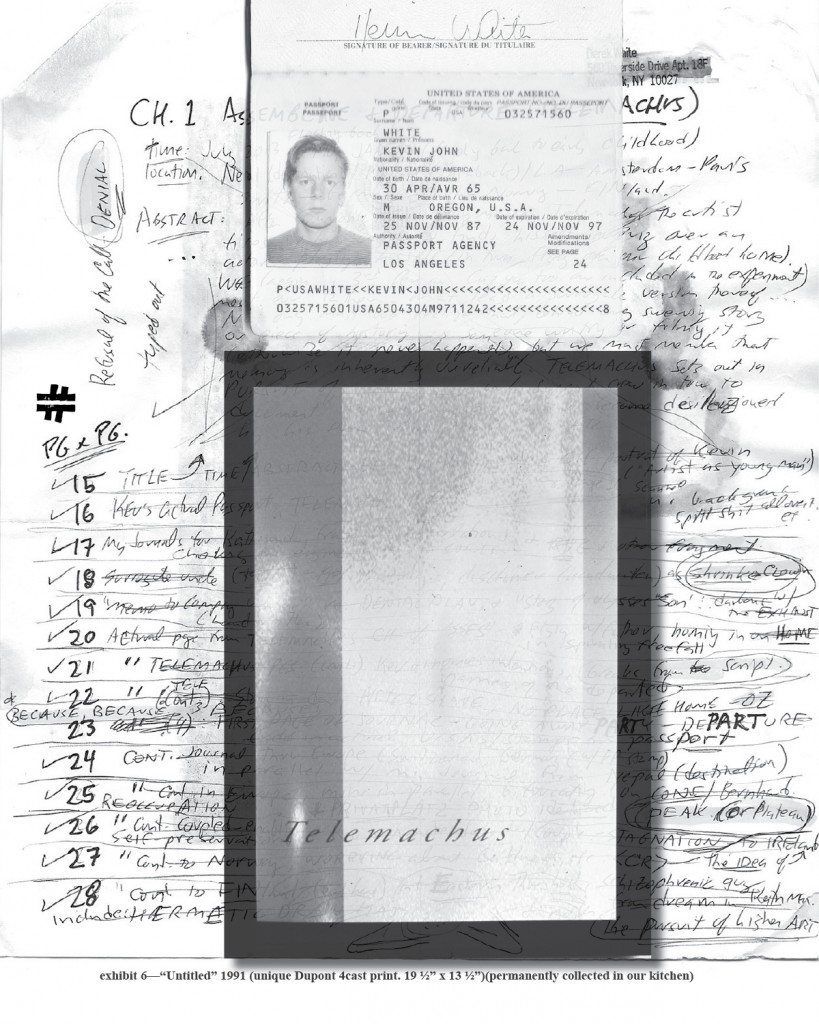

Chaulky White is the pen name given to the combined effort of