Style, Freud, Nietzsche, the uncanny, Poe, Trotsky and Lacan (not to mention a quiver of ressentiment in the direction of existentialism and the modern university system) — Noah Gataveckas is our Dante in a journey through an inferno of intellectual repression, suppression and return (like the corpse of Usher’s sister in the premonitory short story). Nietzsche will not stay dead, it seems, despite our best efforts.

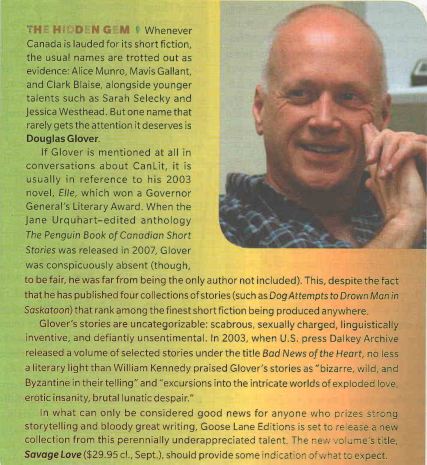

dg

.

I continue to hope that a philosopher-doctor…will some day dare to fully develop the idea that I can only suspect or risk.

— Nietzsche{{1}}[[1]]See Silvia Ons, “Nietzsche, Freud, Lacan,” Lacan: The Silent Partners, ed. Slavoj Žižek (London: Verso, 2006), p. 80.[[1]]

Head

STYLE ISN’T EVERYTHING, but it’s not nothing either. It intrudes upon the message that one tries to communicate – from voice to ear, from one ‘soul’ to another – that comes from within the message itself. In this way, it is like that horror movie staple, the phone call that comes from somewhere inside the house. But since style operates as an automaton of figuration, it is more like an ethereal voice that only exists on the line, beaming into the receiver from the network taken as a whole, that is, the circuit-self. Style is an alien element burrowed in the voice of the other, whose words and mannerisms preflect your own by a quiver-second; you feel yourself return to them for the first time, since they originate from a place “in you more than you,”{{2}}[[2]]See chapter 20 of Jacques Lacan, Seminar XI: The Four Fundamental Concepts of Psycho-analysis, trans. Alan Sheridan (New York: Norton, 1998), p. 263.[[2]] a closet garden in bloom whiff perennial déjà vus. Style is the way that the Signifier stuffs,{{3}}[[3]]See Lacan, Seminar XX: On Feminine Sexuality, trans. Bruce Fink (New York: Norton, 1999), p. 37.[[3]] clutters, before intentionality arrives on the scene to appropriate and set up an ordering of things and a connection between use-values and exchange rates.

A current understanding, which disperses the ‘soul’ into a huff of gaseous matter and takes the ‘otherness’ of the self for granted,{{4}}[[4]]Then again, Lacan’s essay on the mirror stage (1936) noted how the ancient Sanskrit saying “Tat Tvam Asi” (Thou Art That) could be brought to accord with his psychoanalytic teaching.[[4]] sees in style a material trace of the unconscious (individual) and evidence of subjective spirit (particular): not as a “life-style” to be purchased by mastering a pattern of consumer behaviour, but an insistent tendency which finds itself at home in its repetitive unoriginality; whose belatedness and unfashionability, lagging at the back of the pack, allows it to ease into first place in a rat-race without limits or lapcount. Style comes to the fore in an era of fascionistas and apoliticos, when the Name-of-the-Father has been effaced from the writ on the wall, marking the start of the reign of impotence-in-power. The only authority in such prevailing conditions of “ontological anarchism”{{5}}[[5]]The worst representative of this kind of ideological indulgence is found in a lifestyle-anarchist tract by Hakim Bey from 1991, called T.A.Z.: The Temporary Autonomous Zone, Ontological-Anarchy, Poetic Terrorism, available online at: http://hermetic.com/bey/taz_cont.html.[[5]] is what grows from the ground, like how a diamond is formed by centuries of pressure accumulating, through the labours of pain and torture, and leads up to the sublated materials as a result.

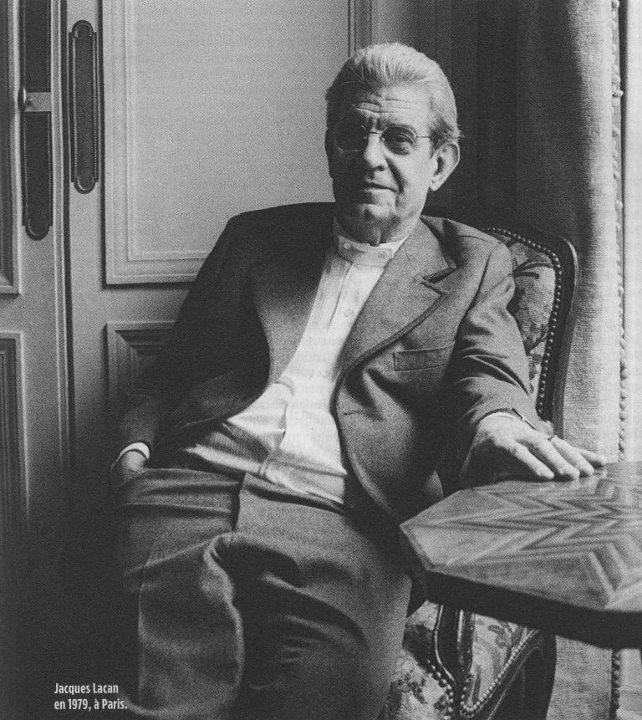

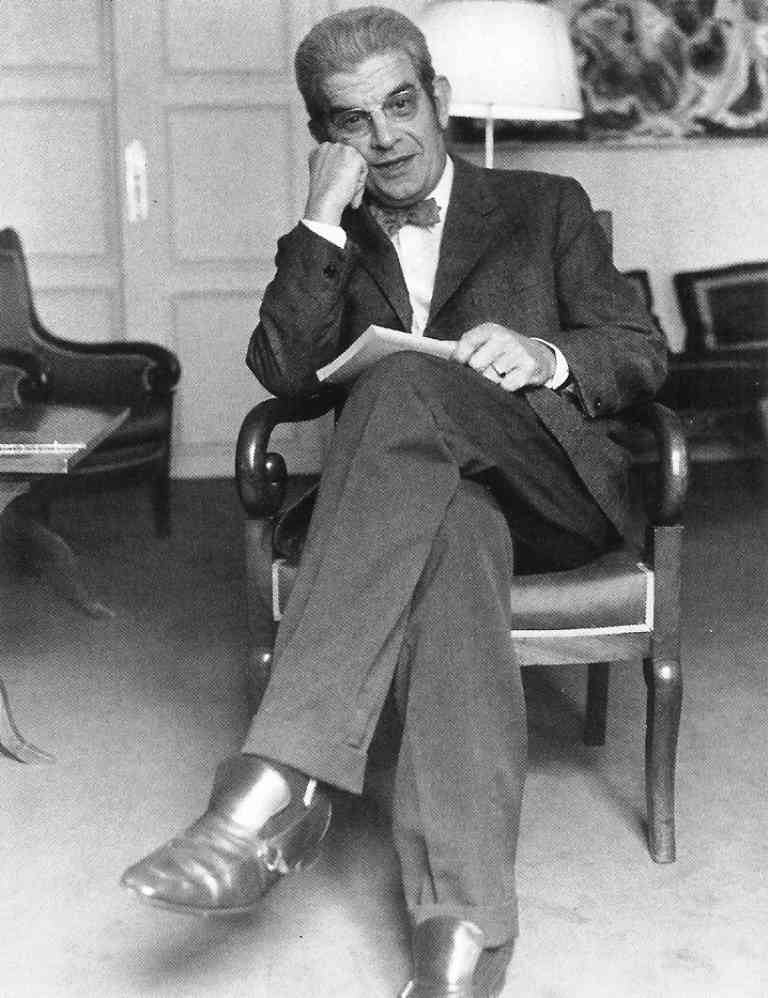

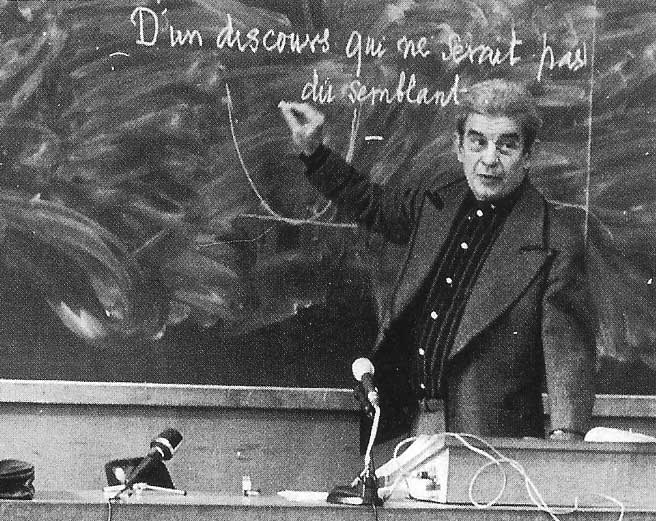

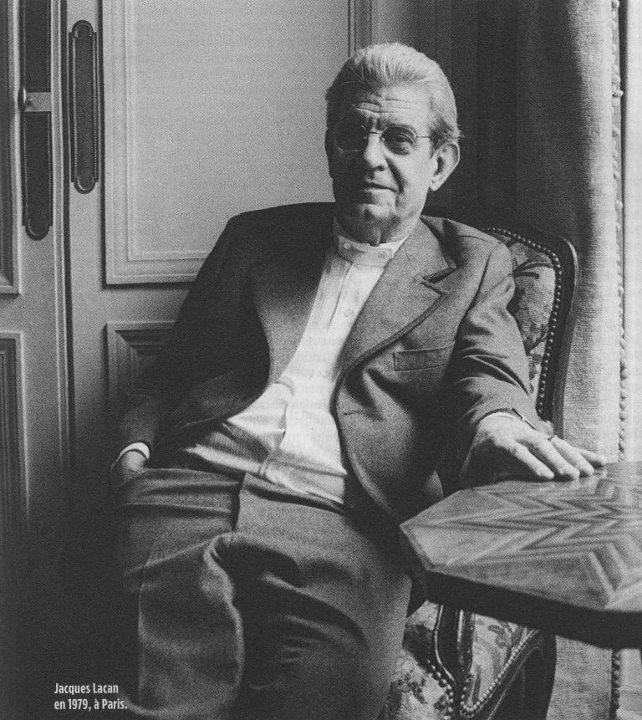

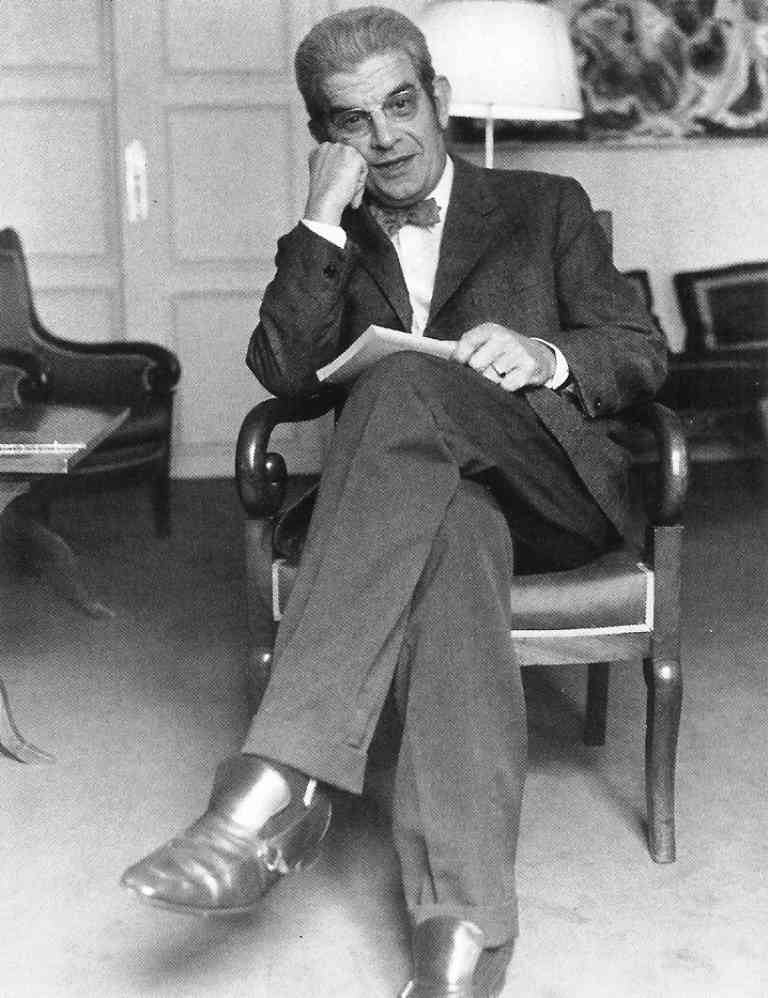

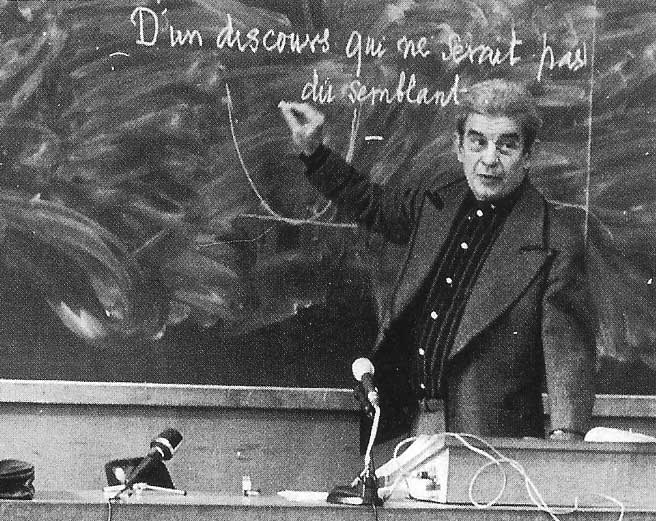

Hyper-condensation and double-displacement distinguish the style of Lacan, only once removed from Nietzsche; he does not need to “return to Freud”{{6}}[[6]]Lacan, “The Freudian Thing, or the Meaning of the Return to Freud in Psychoanalysis,” Écrits: A Selection (New York: Norton, 2002), p. 107.[[6]] in order to appropriate the influence of the former for his own purposes. Lacan’s distance, as we shall see, lets him get far closer to Nietzsche than Freud could ever bear. Vulgar dialectics pose the following formulation: Lacan ‘synthesizes’ (in the sense of ‘reconciles’) Freud’s logos with Nietzsche’s mythos. And yet by keeping alive the polemic tendency embodied in Nietzsche – who aims at a total critique, starting with a critique of totality – Lacan can shed new light on the scope of the Freudian discovery – “a revolution in knowledge worthy of the name of Copernicus”{{7}}[[7]]Lacan, “The Freudian Thing, ” Écrits: A Selection (London: Routledge, 2001), p. 87.[[7]] – in order to push it to the endpoint of its radical trajectory; to overcome the undertaker who, since he could not deflect heaven, initiated the patient and tedious work of raising hell. We owe him our thanks for this. It is Lacan’s point.

Lacan rode around in a Jaguar and partied with surrealists, not afraid to flirt a bit with the threesome of Dionysius, Aphrodite, and Hermes. But like Freud, he also hailed from the weird streets men and women walk in their dreams, the strange and twisted alleyways that spiral Escher-like into the abyss of restless desire and primordial repression. A style developed on a basis of Freudian truth deploys dialectics to devolve how, with the murder of the Anti-Christ by the scientists,{{8}}[[8]]For reference, see the myth of the primordial father from Freud’s Totem and Taboo (1918), in which the ape-man is murdered by the ‘band of brothers’ and society is subsequently founded.[[8]] extremes meet in a post-modern moment: Lacan opens the season of life’s grand festival, to seat Freud at the head of the table, then proceeds to host the Old Man’s roasting; meanwhile Nietzsche remains close, with a good view of the show and, more importantly, the pit. The rest of the guest list is meticulously picked, placed, and orchestrated to compliment each other in syncopation, in tune, in rhythm. But as a result of the grossness of this reconciliation, proceedings cannot help but teeter a little towards calamity, spilling-over-the-side, upheaving, and into the shit.

Lacan’s style explodes the previous standards of evaluating and enjoying prose, of reading and writing in general, with wit and spirit that is upbuilding, uplifting to the heavens of synoptic literacy and absolute knowing, which is to say, a knowledge of the Absolute.{{9}}[[9]]For a full defense of Lacan’s Hegelianism, see chapter 8 of Slavoj Žižek, Less Than Nothing (London: Verso, 2012), p. 508ff.[[9]] So when, in an overture to his own extra-critical tome, Lacan claims that “the style is the man…one addresses,”{{10}}[[10]]Lacan, “Overture to this Collection,” Écrits: The First Complete Edition in English, trans. Bruce Fink (New York: Norton, 2002), p. 3.[[10]] we can be confident that Nietzsche is not to be forgotten. Rather he is to be counted in a short list of cherished others, the priority recipients of Lacan’s career-long in love-letters (to himself, to others…), and one of the still semi-secret ingredients of a rhetorical witches’ brew which, amidst a feast of stale crackers, tastes as remarkably fresh today as when it was first bottled – and really only now, for the first time, after l’âge ingrat, can be said to have begun to mature as a vintage.

Body

Nietzsche is a scandal. Contemporary thought finds it difficult to determine where he fits in the scheme of things. Yet his popularity endures. People keep reading his works. We do not want to forget him, to allow his name to fade into the obscurity of the past, at least not yet. This is what makes a problem for those who do not know what to do with his continued relevance.

It manifests most markedly in the environs of academia. Specifically, the academic industrial-complex has been utilized to promote a vague category called “existentialism”{{11}}[[11]]This term, popularized by Sartre in the 1950s and disowned soon afterwards, has shamefully been seized upon by the academic and media ideological state apparatuses to perpetuate a mystified account of unique authors such as Kierkegaard, Dostoyevsky, Nietzsche, Heidegger, and others; as if the differences between these disparate sources could simply be cast as ‘variants’ or ‘flavours’ of a ‘common’ project which they all worked on together, called “existentialism.”[[11]] a defensive manoeuver to contain the spread and influence of his still-untimely meditations. This countermeasure aims at preventing the unification of the various hyper-professionalized, atomized disciplines — a state of affairs which investors and rectors have had to work hard over the years to engineer — within Nietzsche’s gaping abyss of negativity and radical commitment to critique.{{12}}[[12]]And yet Paul Feyerabend exists, whose “anarchic theory of knowledge” approximates what the sciences are missing, in terms of an avowed Nietzschean influence. Thus despite the efforts made to stem a creeping negativity, by isolating Nietzsche and pegging him in the philosophy department as an “existentialist,” the night-terror of critical criticism that he represents, like the shadow-monster from the cheesy remake of House on Haunted Hill (1999), rises from the basements of the Academy, to invade every department and eventually consume the entire schoolhouse. Nietzsche’s negativity, taken in this way, is bigger than himself, has the capacity to outgrow its historical confines.[[12]]

After all, what if Nietzsche’s right? Isn’t the message that he delivers – one is tempted to say preaches – the active negation of what passes for an “education” today, humanities or otherwise? How can one trust his enemies to explain and teach him?

Nietzsche’s discourse resists spinful interpretating toward liberalism. His work upends the ridiculous idea that philosophy and critical thought are “subjects” one must go to school to get a degree in before being able to speak a word to them. Professional philosophy is an analytic contradiction, like a married bachelor. Thanks to Nietzsche (but also Marx, whose critique of capitalism dealt a theoretical deathblow to the university ideology first,{{13}}[[13]]In a sentence, the ‘sanctity’ of the university discourse was forever tarnished when Marx showed “the ideas of the ruling class are in every epoch the ruling ideas, i.e. the class which is the ruling material force of society, is at the same time its ruling intellectual force.” See The German Ideology (1845), available online at: http://www.marxists.org/archive/marx/works/1845/german-ideology/ch01b.htm.[[13]] decades before Nietzsche ever got the opportunity to pick the fight), we now know that university institutions are a reaction to the real potential of social critique that unfolds as an immanent process within society itself. Nietzsche’s de(con)struction of “knowledge” and “truth” reflects the self-inflicted implosion of his professional career (that is, as a professor of Classics at the university of Basel in Switzerland), a development which at the same time precipitated his maturation as a thinker and writer into the Super-Nietzsche we have come to recollect today: a singular figure in the history of thought and philosophy who provokes awe and anxiety alike as a stand-in for Zarathustra himself — in spite of his all-too-humanities, foibles, flaws, and quixoddities.{{14}}[[14]]The historical biography of the man, Friedrich Wilhelm Nietzsche (1844 – 1900), does not begin to resemble the (imaginary) heroic figures of action whom, over the course of his texts, he lauds with love and admiration, like an immensely exalted father in the flesh; like Marx, Nietzsche did preach a philosophy of praxis (at least in the abstract), but unlike Marx, Nietzsche’s body remained tied to the routine of passive contemplation, of sickly recovering – in this way (i.e. the form of ‘doing philosophy,’ of sheltered thought), he never broke from his roots in Schopenhauer (even if he broke with Schopenhauer in terms of content).[[14]]

The school-machine generates legions of ‘experts’ in order to convince regular people not to think on the supposed ground that ‘professional,’ much more impressive people (with diplomas!) are already doing this vital ‘job’ for them, for us. We should trust them and try not to get in their way, goes the moral of our times. The control of knowledge becomes the knowledge of control. This is something Nietzsche opposed, as one who was driven out of the academy for challenging its pretensions. Its religious and market prejudices had become too outlandish, already in the second half of the nineteenth century, for him — as a self-respecting philosopher, understood in the Socratic sense, employing the methods of ironic negativity{{15}}[[15]]On this point, compare Kierkegaard’s Masters thesis: The Concept of Irony with Constant Reference to Socrates (1841).[[15]] —– to be able to stay in school and at the same time remain a free thinker. Those who come into contact with Nietzsche’s writings over the course of an arts degree are driven to wonder what the point of it is — why higher education? — when the content they are being asked to make reports on (and get graded on!) negates the very notions of “reports,” “grades,” and “higher education” altogether, revealing these as hairshirts worn only to appease the masochism of those conformists-in-training; or as fetish-gifts, used to promote and instill the cult of “success”{{16}}[[16]]It is interesting to note, from the perspective of the critique of ideology, that Lacan would regularly refer to certain words during his seminars in English, to ridicule certain ideological positions of English-speaking societies. For example, he did this with words such as “success,” “self-made man,” “the American way of life,” etc.[[16]] amongst the next generation of Eichmanns.

Under a bourgeois education system, it is to be expected that Nietzsche’s message would come to be sterilized, anesthetized, fractured, and segmented into pellets, for casual consumption, like popcorn in a snack mix.{{17}}[[17]]One can imagine the advert on the packaging: “Existential’sms! All your faves in one bag! Krazy Kierkegaards! Neat Nietzsches! Dope Dostoyevskys! Hot Heidegger! Sweet Sartres! Cool Camus!”[[17]] The unity of his thought gets dissolved into tidbits and catchphrases to be sprinkled throughout the humanities as a whole, dissipated into a mystic fog of pseudo-Zoroastrianism and neo-Thrasymichusism.{{18}}[[18]]Cf. book I of the Republic of Plato, where Thrasymichus shows that the Nietzschean understanding of “justice” that in the present he is theoretically famous for, in fact, predates him by millenia.[[18]] But the initiative of youth, hungry for answers and eager to learn the ways in which they have been betrayed by their progenitors,{{19}}[[19]]A generation of parents and guardians, due to their short-sightedness and complicity with the capitalist system, have effectively sold their children and grand-children, an entire series of cohorts, into slavery and to be used as human sacrifices to the pagan god Baal, so that they might receive an upgrade on the size of their television screens. This is how the baby-boomers of North America and Europe will come to be remembered, that is, by the survivors of the upcoming catastrophe: as the generation who saw no irony in Swift’s modest proposal, and was willing to make a deal for an all-time low, something the equivalent of a hot tub.[[19]] follow one signifier after another in pursuit of elucidation. When they are not bogged down by the drills and tests designed to distract them from actually learning anything of any merit or interest to their immediate lives (as living bodies forced to engage with (political) economies in order to reproduce themselves over time), students read Nietzsche in spare hours in preparation for dropping out. Once turned on, tuning into Nietzsche’s frequency is a fast track to hitting the pavement.

Nietzsche’s open attack on the institutionalized knowledge of the churches and universities — reminiscent of Socrates’ blistering campaign waged against the knowledge-for-profit services sold by the Sophists to aspiring tyrants — proceeds on the basis of a ruthless critique of everything (re)currently existing.{{20}}[[20]]Perhaps the most important theoretical difference between Marx and Nietzsche can be articulated along these lines, insofar as Marx’s critique was more radical than Nietzsche’s, at least when it came to the notion of history. Whereas Nietzsche lauds the nobility of the past as a mythical standpoint from which to critique the ‘degenerated’ present situation (the cause of which he tellingly displaces in Christianity as opposed to capitalism), Marx’s critique has no illusions about the ‘great men’ of ancient times. As a materialist method of combining thought and practice, Marxism’s “ruthless criticism of all that exists” (“Letter to Ruge”) does not need to rely on any kind of ‘original’ historical position, from which our current ‘misbegotten’ age has fallen into decline. On this basis, one can claim that Nietzsche’s critique is not self-reflexive to the most radical degree: while all-encompassing in terms of its scope, it does not include its own presuppositions (of “strength,” “will to power,” “Europe,” “eternal recurrence,” etc.) into its critical purview; an over-accumulation of negativity is offered in the place of the teaching about the “negation of the negation”; an infinite quantity of deconstructive analysis stands in for an infinity of infinities (Cantor) – the former of which opens the door to textual idealism a la Derrida, while the latter of which constitutes a “great materialist breakthrough” (Žižek, Less Than Nothing, p. 227).[[20]] This means that his critique — or, as he dresses it up, his “revaluation of all values”{{21}}[[21]]See Nietzsche, “The Anti-Christ,” The Anti-Christ, Ecce Homo, Twilight of the Idols and Other Writings, ed. Aaron Ridley and Judith Norman (Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press, 2005), p. 66.[[21]] — goes far beyond the sins and failings of the churchaversities. Even Marxists are made to feel a bit put off, if not outright uncomfortable{{22}}[[22]]For example, see how uneasy Lukács is made in “The Destruction of Reason” (1952), where he describes Nietzsche as being one who possessed “a special sixth sense, an anticipatory sensitivity to what the parasitical intelligentsia would need in the imperialist age, what would inwardly move and disturb it, and what kind of answer would most appease it. Thus he was able to encompass very wide areas of culture, to illuminate the pressing questions with clever aphorisms, and to satisfy the frustrated, indeed sometimes rebellious instincts of this parasitical class of intellectuals with gestures that appeared fascinating and hyper-revolutionary.” Available online at: http://www.marxists.org/archive/lukacs/works/destruction-reason/ch03.htm[[22]] when exposed to Nietzsche’s thought: at best, adopting an aggravated ambivalence, a pat dismissal of his petit-bourgeois background and individualism; at worst, repeating some tenuous claims in an attempt to dismiss him without so much as a consideration, by insinuating the link with Hitlerism that bourgeois commentators are just as quick to point out when faced with the prospect of radicalized Nietzschean will-to-nihil.{{23}}[[23]]Usually by way of the composer Richard Wagner, who was an anti-Semite, and whose music was used posthumously by the Third Reich. Nietzsche kept company for a time with Wagner, that is, until Nietzsche’s admiration turned to enmity. For example, see Nietzsche’s account in Nietzsche Contra Wagner, written in 1888 and first published in 1895.[[23]] After all, Nietzsche was no Marxist — but then the problem reappears once again, where to fit him? Why would Marxists appeal to the philosophy of someone whose ideas were formed, essentially, as a middle-class reaction to Marxism? Whose literary style is, although admittedly stunning, nonetheless derivative of some of the best works of Marx and Engels?{{24}}[[24]]Nietzsche’s writing, at its most polished, is never as dazzling as Marx’s The Eighteenth Brumaire of Louis Napoleon; at its most raw and concrete, The Will to Power is not so ambitious and absorbing as the Grundrisse; and for a weird mixture of the two, see the late writings of Engels, such as his retroactive introductions to The Civil War in France and The Class Struggles in France, from 1891 and 1895 respectively. There are turns of phrase and rhetorical flourishes that Engels makes in these documents which are reminiscent of Nietzsche; and since some of Nietzsche’s works had been released by 1890, it is entirely possible that Engels could have read them and – who knows? – borrowed a trick or two. Then again, Engels seemed to have beat Nietzsche to the punch about the monumental foolishness of Dühring, with Anti-Dühring having been published first in 1877, while Nietzsche only first began to polemicize against the anti-Semitic ideologist of “heroic materialism” in the 1878 text Human, All Too Human, an engagement that extended all the way past Beyond Good and Evil (1886) and On the Genealogy of Morals (1887), to The Will to Power, which was assembled posthumously from Nietzsche’s late notes and manuscripts, and continued to batter Dühring, i.e. calling him a “barbarian” (§130).[[24]]

Of the orthodox Marxists,{{25}}[[25]]A list typically taken to include Marx, Engels, Luxemburg, Lenin, and Trotsky as the key five.[[25]] Leon Trotsky is probably the most confident in this arena. In a document from 1900 titled “On the Philosophy of the Superman,” he calls Nietzsche the prophet of a “proud individualism” which, Trotsky assures us, it is even possible to practice unconsciously: “being Nietzschean [does not] mean being an adventurer of finance or a vulture of the stock market. In fact, the bourgeoisie has spread its individualism beyond the borders of its own class… [Many people] probably are even unaware of Nietzsche’s existence insofar as they concentrate their intellectual activity on an entirely different sphere; on the other hand, each of them is a Nietzschean despite himself.”{{26}}[[26]]Trotsky, Leon, “On the Philosophy of the Superman,” trans. Mitchell Abidor, available online at Marxists.org.[[26]] Presumably, this means that Nietzsche’s “will to power” has spread and melded with the bourgeois ideology of present-day society. The conclusion of the article, though, rejects the philosophy of the Übermensch: “we find sterile such a literary and textual attitude towards the writing rich in paradoxes…whose aphorisms are often contradictory and in general allow for dozens of interpretations.”

Then why does Trotsky, years afterwards, continue to read and write about Nietzsche, even after the tumultuous, transformative events of 1905?{{27}}[[27]]See Trotsky, 1905, available online at: http://www.marxists.org/archive/trotsky/1907/1905/[[27]] Credit is due to the archiphile Ross Wolfe for unearthing and translating an article from 1908 called “Starved for ‘Culture'” in which Trotsky continues to expound upon the influence of Nietzsche. It is worth quoting here at length: “In the West, he appeared as the final, most extreme word in philosophical individualism because he was also the negation and overcoming of petit-bourgeois individualism. But for us Nietzsche was forced to perform a quite different task: we smashed his lyrical philosophy into fragments of paradoxes and threw them into circulation as the hard cash of a petty, pretentious egoism… Nietzscheanism [was] the muddled, romantic, chaotic outburst of a new intellectual health… Nietzsche was the genuine negation and overcoming of Kant and the Kantians… Whereas our Kantian appeared for the sake of overcoming Nietzscheianism, he in turn was mastered — legitimized, and was legitimated… A narrow line traces out a new fissure in our social life, calling for a new ideology, such as the one Europe now casts down upon us, corresponding to the riches of its philosophy, its literature, its art: Nietzsche…Kant…the Marquis de Sade…Schopenhauer…Oscar Wilde…Renan… That which exists in the West was born in spasms and convulsions, or else was composed by imperceptible degrees, as the product of a complex cultural epoch…”{{28}}[[28]]See “Some hitherto untranslated sections of Trotsky on Nietzsche (1908),” The Charnel-House, available online at: http://rosswolfe.wordpress.com/2013/01/06/some-hitherto-untranslated-sections-of-trotsky-on-nietzsche-1908/.[[28]]

Trotsky, despite his previous reservations, kept reading Nietzsche, did not throw him out along with the rest of the dreck.{{29}}[[29]]As late as 1924, in Trotsky’s writings on “Literature and Revolution,” he invokes Nietzschean themes and language to describe a “new man” for a new society: “the new man of the future will want to laugh… the new man will love in a better and stronger way than did the old people, and he will think about the problems of birth and death. The new art will revive all the old forms, which arose in the course of the development of the creative spirit” (available online at: http://www.marxists.org/archive/trotsky/1924/lit_revo/ch08.htm).[[29]] Indeed, Trotsky counted Nietzsche alongside the “riches” of Europe’s “philosophy, its literature, its art” (along with de Sade!!). Which returns us to the problem at hand: Whether the schools are bourgeois or proletarian, it seems, the figure of Nietzsche threatens to upset the ‘official’ curriculum, as an oddity, a leftover, outside what otherwise fits together like a completed puzzle. In a way Nietzsche is like Trotsky himself, insofar as the latter’s reputation was never resuscitated in the Soviet Union after Stalin had him smeared and assassinated (this is unlike Zinoviev and Bukharin and others, whose images were rehabilitated posthumously under the Khrushchev regime). Trotsky’s ghost still haunts the political Left{{30}}[[30]]See Derick Varn, “Interview with Noah Gataveckas on the Ted Grant and the Specter of Trotskyism,” The (Dis)Loyal Opposition to Modernity blog (27 Mar 2013), available online at: http://skepoet.wordpress.com/2013/03/27/interview-with-noah-gataveckas-on-the-ted-grant-and-the-spectre-of-trotsky/[[30]] due to an improper burial service; in a similar way, Nietzsche’s presence is still with us, threatening to burst forth from the tomb, like a vampire, or the corpse of the sister in “The Fall of the House of Usher.”

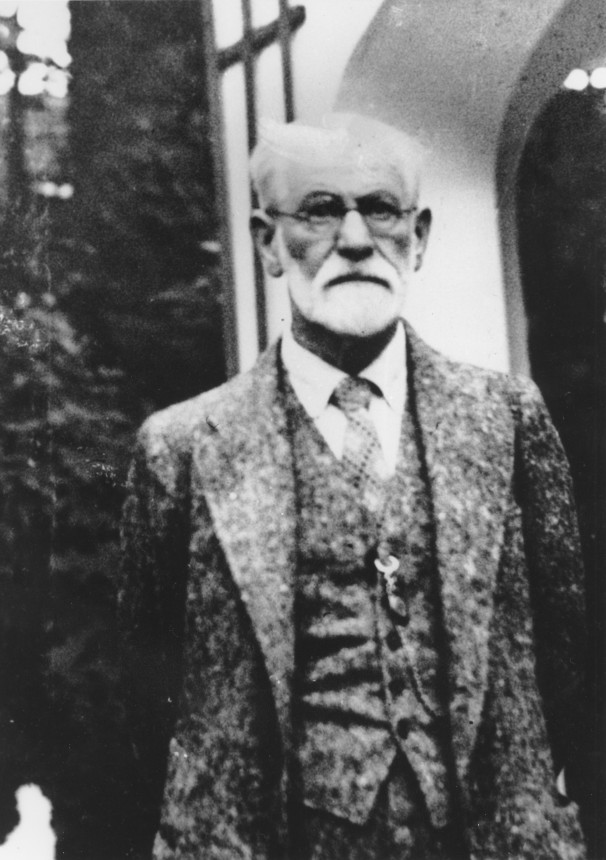

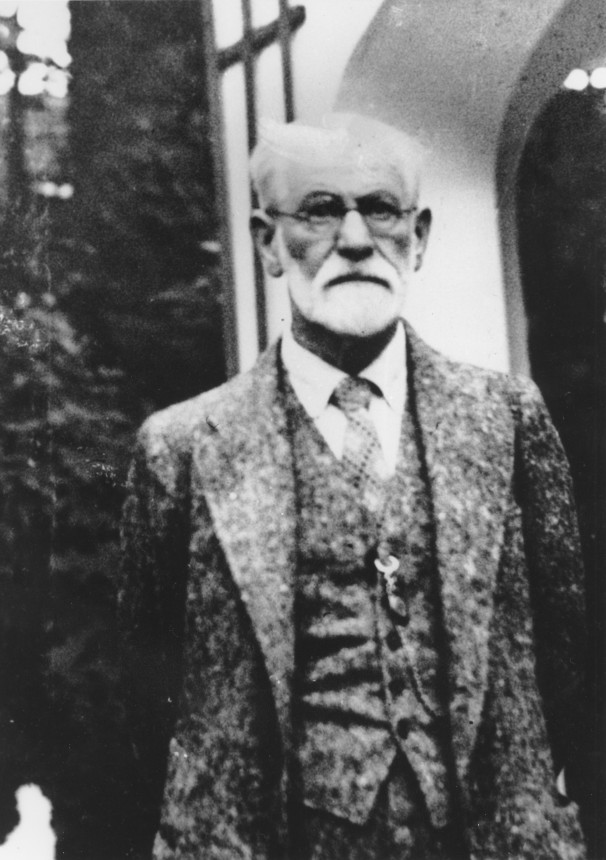

What is more: in the way that Poe’s macabre short stories are lauded by psychoanalysts for being “powerful in the mathematical sense of the term”{{31}}[[31]]Lacan, “Overture to this Collection,” Écrits: The First Complete Edition in English, p. 4.[[31]]due to their eerie precognition of psychoanalytic theory, the science of psychoanalysis is also unable to escape from the gravitational pull of Nietzsche’s dark star. Here it behooves us to consider an exceptional confession that was made by Freud in 1914,{{32}}[[32]] A pivotal year in Freud’s development. Freud’s career, in terms of its theoretical progression, can be roughly divided into four sections: pre-1895; 1895 – 1913; 1914 – 1926; 1927 – 1940. The theory that he has at the end of the journey is different than the one he starts with; he has picked up some ‘friends’ along the way – like the “death drive” – which were not present at the expedition’s outset.[[32]] a confession that establishes the kind of relationship that the father of psychoanalysis had with the murderer of God: “I have denied myself the very great pleasure of reading the works of Nietzsche…with the deliberate object of not being hampered in working out the impressions received in psychoanalysis by any sort of anticipatory ideas. I had therefore to be prepared — and I am so, gladly — to forego all claims to priority in the many instances in which laborious psychoanalytic investigation can merely confirm the truths which the philosopher recognized by intuition.”{{33}}[[33]]See Silvia Ons, “Nietzsche, Freud, Lacan,” Lacan: The Silent Partners, p. 79.[[33]]

In his “Autobiographical Study” from 1925, Freud is even more explicit in tracing his theoretical genealogy to Nietzsche and beyond: “I read Schopenhauer very late in my life. Nietzsche, another philosopher whose guesses and intuitions often agree in the most astonishing way with the laborious findings of psycho-analysis, was for a long time avoided by me on that very account; I was less concerned with the question of priority than with keeping my mind unembarrassed.”{{34}}[[34]]See Mikkel Borch-Jacobsen and Sonu Shamdasani, The Freud Files: An Inquiry into the History of Psychoanalysis (New York: Cambridge University Press, 2012), p. 106.[[34]]

There is much of interest in these statements. First, Freud’s self-avowal of his “anxiety of influence”{{35}}[[35]]See Bloom, Harold, The Anxiety of Influence (New York: Oxford University Press, 1997), p. 5.[[35]] in relation to Nietzsche, who he accuses of inventing “anticipatory ideas.” Second, the way that this connects to Lacan’s argument on behalf of a structuralist Freud — insofar as Freud is credited with “anticipating” Saussure.{{36}}[[36]]See Lacan, “The Direction of the Treatment and the Principles of Its Power,” Écrits: A Selection, p. 249.[[36]] Third, the flagrant openness of Freud’s avowal: what does it mean to say that Freud repressed Nietzsche’s influence on the development of his psychoanalytic thought, when Freud is the first one to admit this, as it were, “gladly”? Fourth, the attribution of the genius of Nietzsche to his “intuition,” a claim which is basically repeated by Žižek when he says: “Nietzsche possessed an unerring instinct that enabled him to discern, behind the sage who preaches the denial of the Will to Life, the ressentiment of the thwarted will…”{{37}}[[37]]See Žižek, The Ticklish Subject: The Absent Center of Political Ontology (London: Verso, 2000), p. 11.[[37]] But what is this “unerring instinct,” this perfect “intuition”? Fifth and finally, it poses the question of science and its practice: what was Freud’s method, his style of empirical analysis, such that, through independent verification of the “impressions received in psychoanalysis,” he could produce a different kind of symbolic authority than that which stems from historical transmission and, ultimately, hermeneutics?

Freud appears to be aware that psychoanalysis corresponds (in the sense of coincides) with the most uncanny and insightful formations (one might call them deductions) of Nietzsche, shrouded as they are in mythical prose and slippery “paradoxes.” However, he also suggests that he must protect himself from Nietzsche’s influence, in the same way that a lab technician will prevent an experiment from being tampered with, or a judge will sequester a jury, to block them from being spoiled by outside opinions. All of this involves a construction of a deliberate ignorance, a purposeful silence, which can allow itself to be corrected, not by peers but by a qualitative in-gathering of experience that gets carried out in accordance with the best phenomenological traditions that emerged in the wake of the Germanic philosophical revolution of the 19th century, which was inaugurated by the dialectish thought of Kant and his compatriots.{{38}}[[38]]Only “ish,” insofar as antinomic thought (cf. Kant’s Critique of Pure Reason) is less than dialectical thinking. Credit for the perfection of the expression of the dialectic in a literary (stylistic) form, of course, goes to Hegel and Marx. The superiority of the combination of these two is demonstrated on a daily basis in the work of Žižek, who adopts the positive position of “dialectical materialism” by way of a radical reading of Hegel that draws out the already-materialist aspects in Hegel’s writing, thereby dissolving the traditional distinction stressed by Marx (but especially Engels), that Hegel’s “idealism” had been supplanted by Marx’s “materialism” (a claim which of course is true, if you take into account the Marxist understanding of materialism (cf. Theses on Feuerbach III), but which does not prevent it from getting used by materialists-in-name-only (faux-Marxists) to justify the outright rejection and denigration of Hegel’s contribution – that is, as the founder, cornerstone, backbone, etc. – to the science of dialectics, once it is taken as a science (which may or may not be done under the banner of “philosophy,” it doesn’t really matter)).[[38]]

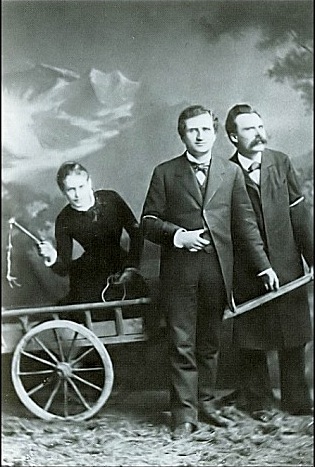

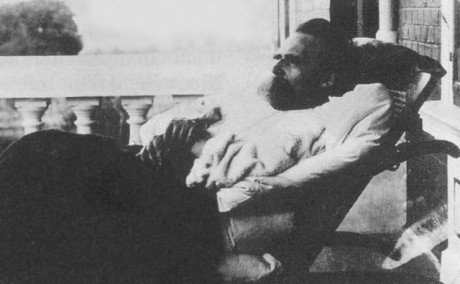

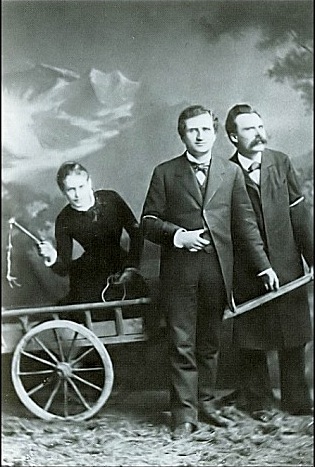

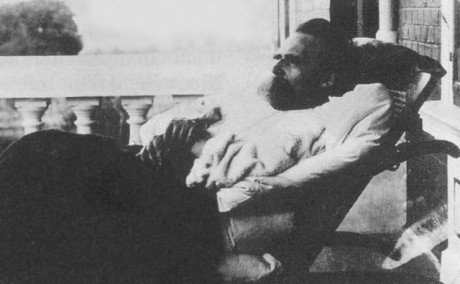

So Nietzsche appears, from this perspective, as a proto-Freudian, or rather as the Ur-Freud. On the totem, Nietzsche’s raw soil undergirds Freud’s establishment of the symbolic order of psychoanalytic knowledge, which is in the rational and scientific language of his day, free from the Goya-scenes that haunt the more feverish pages of Nietzsche. Playing the role of the primordial father in relation to Freud, he is the taboo dad whose death becomes the condition of freedom, which Freud is able to attain through employing the scientific terms of his time to develop a new mode of discourse. Nietzsche’s dream of the gay science, the joyful science (so close, the German Freund means boyfriend, lover), comes true for the first time with the founding of psychoanalysis. Before this point, it was merely a ‘scene,’ as goth and emo as the 1882 photo of Nietzsche with Lou Salomé and Paul Reé suggests.

And the science of desire and jouissance, despite its frills, should be admitted to possess a much higher degree of clarity and operational value, in a medical sense, than Nietzsche’s mere appeals and parables, insofar as only one stakes itself on a concrete method which, other than Marxism, has the power to act simultaneously on the subjects and objects of historical development. We should be able to see the necessary difference between Nietzsche and Freud, and how the latter should be seen to ‘sublate’ and ‘overcome’ the former; that is, even if we wonder to the degree that the latter rests implicitly on the astral visions of prior trips; imaginings which, oracular in their reflectivity, outshine the sun, like an eclipse which magnifies the light, reflecting it and focusing it into a beam which, if met by any gaze, blinds.

This leads us to consider Lacan’s appraisals of Nietzsche, as one more mellow about this subject than Freud. Unlike the Old Man, who refers to Nietzsche in the same way that Aquinas casually came to refer to Aristotle, as “the philosopher,” Lacan can tell a joke or two about the subject, perhaps spread some rumours, and be self-certain enough to see how the uniqueness of psychoanalysis will allow it to survive, regardless of whatever the verdict on Nietzsche shall be in the coming years. Lacan shows that Nietzsche’s “eternal recurrence” is not the same as the psychoanalytic notion of “repetition,”{{39}}[[39]]Which is modeled on Kierkegaard’s notion of “repetition,” but at the same time should be argued to stand as an authentic contribution made by Freud to the conceptual canon of theoretical thought, insofar as Freudian repetition comes along with his theory of the “drive,” the “death drive,” i.e. urge-to-repeat. See Lacan, “On a Purpose,” Écrits: The First Complete Edition in English, p. 307.[[39]] a point which was actually first made by Freud, but needed to be repeated.{{40}}[[40]]See Freud, Beyond the Pleasure Principle, ed. Todd Dufrense, trans. Gregory Richter (Peterborough, ON: Broadview Editions, 2011), p. 64.[[40]] Still, Lacan goes farther in explaining where Nietzsche fits in, at least vis-a-vis the rest of the Eurocanon. According to Lacan, Nietzsche “is a nova as dazzling as it is short-lived.” He adds, however, that this is still not so much as Balthazar Gracian or La Rochefoucauld, who shine as “the brightest stars” of “a milky way in the heavenly vault of European culture.”{{41}}[[41]]Lacan, “The Freudian Thing,” Écrits: The First Complete Edition in English, p. 339.[[41]] At another point, in his Seminar I, Lacan slights both Nietzsche and Rochefoucauld, considering them to be “insignificant” when compared to Gracian, in particular his books The Oracle and Criticón.{{42}}[[42]]Lacan, Seminar I: Freud’s Papers on Technique, trans. John Forrester (New York: Norton, 1991), p. 169.[[42]]

This is a paradoxical gesture: merely mentioning Nietzsche here is, to put it one way, a ‘shout-out,’ since it is also to hold him in the same company as these other “stars,” if only in a supporting role. But it is still an attack (does one dare to suggest, “displacement”?) on the commanding influence of Nietzsche, as evidenced by Lacan’s election of Gracian and, later, Joyce,{{43}}[[43]]For example, see Lacan, Seminar XX: On Feminine Sexuality, p. 37.[[43]] into the position of kingmakers in the department of what gets counted for stylistic substance today, at least, according to Lacan. He appreciates the effort, but this doesn’t save Nietzsche from not making the cut: hence his emo-ness, hence his picked-last-in-gym-class mentality. This trauma is devastating for Nietzsche, since for him there would be nothing more humiliating than finishing in fourth place at the philosophy Olympics.

It takes psychoanalytic thinking to understand the extent of Nietzsche’s folly (however praiseworthy though it may be), insofar as his loud posturing only sells the appearance of an atheism which, unconsciously, remains betrothed to God-in-the-sky. Imagine that Nietzsche the madman runs into the street and yells, at the top of his lungs, “God is dead!” He repeats this gesture at the same time each morning, and twice on Sundays. Are we to believe that he really believes what he says? Here is where Lacan’s alternative formulation of atheism comes to the fore: “the true formula of atheism is not God is dead – even by basing the origin of the function of the father upon his murder, Freud protects the father – the true formula of atheism is God is unconscious.”{{44}}[[44]]Lacan, Seminar XI: The Four Fundamental Concepts of Psycho-analysis, p. 59.[[44]]

While Lacan tended to deflect questions concerning the belief in God — said it didn’t matter to him, one way or another, personally — he also adopted the philosophical position of “dialectical materialism,”{{45}}[[45]]See Žižek, Less Than Nothing, p. 780.[[45]] that is, the same position of Marx and Lenin,{{46}}[[46]]For an exposition of this position, see V. I. Lenin, “On the Significance of Militant Materialism,” 1922, available online at: http://www.marxists.org/archive/lenin/works/1922/mar/12.htm.[[46]] that entails a rejection of theological beliefs and religious superstitions. All of this adds up to Lacatheism, Lacanian atheism, and when taken together with Žižek’s explicitly avowed atheism,{{47}}[[47]]He has described himself as a “militant atheist” at multiple public speaking engagements, many of which are available on the internet.[[47]] it is clear that Lacanian thought, i.e. psychoanalysis, is really the sine qua non of atheism in the modern age. Lacan thus manages to accomplish something that Nietzsche set out to do but could not bring himself to fully fathom, once he got lost down the highway of his private metaphysics, a Neverland-like Pleasuredomain that he so-called, contingently, “will to power.” An immensely exalted father continued to ape in the shadows of Nietzsche’s fantasy-world, disavowed, but therefore all the more awful. Lacan in contrast was able to relieve himself from the grasp of God, able to catch a glimpse of what lies beyond secular thinking, beyond the immensely frightful shadow of the Big Buddha, and convey a bit of his vision to the rest of us still stuck in Plato’s cave. He is Nietzsche un-Nietzsched, castrator of castration, negating negation itself.

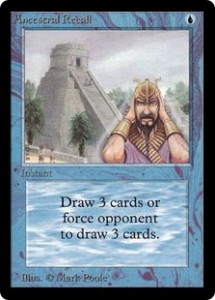

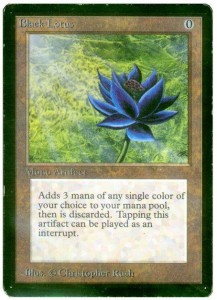

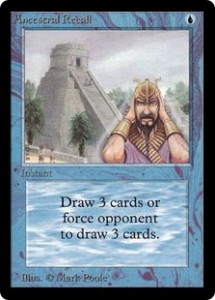

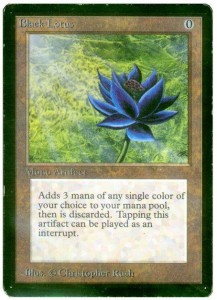

Nietzsche and Lacan emerge from the same Eurotradition of thought. It includes the “early modern” thinkers of Renaissance and Enlightenment but also the mystics and radicals of the Catholic Church, Plato and Aristotle, Sophocles and Homer, etc. etc., who all attempt to account not only for their own times but the entire “nightmare of history,” as both Marx and Joyce described it.{{48}}[[48]]See Joyce, Ulysses (London: Flamingo, 1994), p. 42.[[48]] It is impossible to hold the world in your right hand, but attempting to do so produces a specific discourse, nonetheless, a discourse that reflects the conditions of its production, and is not without noteworthy features of its own. But here is where Lacan disjoints from Nietzsche. Insofar as Lacan compasses Nietzsche in his repertoire, combined with many others and taken to higher stage (since Lacan takes the tradition of Nietzsche and Schopenhauer alongside the Freudian system which — why not? — should be counted as an ontology in its own right, a materialist phenomenology of the symptom qua signifier), the equation is obvious: Lacan > Nietzsche, or, Lacan = Nietzsche + MORE (at the very least, Freud’s development upon and critique of Nietzsche’s merely mythological articulation, halfway-deduction, of what makes for modern psychology; also a more coherent politics; also Heidegger; also Saussure; also Lévi-Strauss; also Joyce; etc. etc.). Lacan holds Nietzsche as a card in a big deck, another name to be played alongside the rest, just as those writing in the present are permitted to use the Lacan card — a trump if there ever was one, or a joker.{{49}}[[49]]If, to use relations from Magic: The Gathering, Nietzsche is Ancestral Recall, then Lacan is Black Lotus; likewise, to use relations from Pokemon, if Nietzsche is Arceus Lv. X, then Lacan is Arceus Ex.[[49]]

Nietzsche and Lacan emerge from the same Eurotradition of thought. It includes the “early modern” thinkers of Renaissance and Enlightenment but also the mystics and radicals of the Catholic Church, Plato and Aristotle, Sophocles and Homer, etc. etc., who all attempt to account not only for their own times but the entire “nightmare of history,” as both Marx and Joyce described it.{{48}}[[48]]See Joyce, Ulysses (London: Flamingo, 1994), p. 42.[[48]] It is impossible to hold the world in your right hand, but attempting to do so produces a specific discourse, nonetheless, a discourse that reflects the conditions of its production, and is not without noteworthy features of its own. But here is where Lacan disjoints from Nietzsche. Insofar as Lacan compasses Nietzsche in his repertoire, combined with many others and taken to higher stage (since Lacan takes the tradition of Nietzsche and Schopenhauer alongside the Freudian system which — why not? — should be counted as an ontology in its own right, a materialist phenomenology of the symptom qua signifier), the equation is obvious: Lacan > Nietzsche, or, Lacan = Nietzsche + MORE (at the very least, Freud’s development upon and critique of Nietzsche’s merely mythological articulation, halfway-deduction, of what makes for modern psychology; also a more coherent politics; also Heidegger; also Saussure; also Lévi-Strauss; also Joyce; etc. etc.). Lacan holds Nietzsche as a card in a big deck, another name to be played alongside the rest, just as those writing in the present are permitted to use the Lacan card — a trump if there ever was one, or a joker.{{49}}[[49]]If, to use relations from Magic: The Gathering, Nietzsche is Ancestral Recall, then Lacan is Black Lotus; likewise, to use relations from Pokemon, if Nietzsche is Arceus Lv. X, then Lacan is Arceus Ex.[[49]]

Yet there is no card that will stop history from continuing to accumulate under the emotionless supervision of Benjamin’s angel of wreckage.{{50}}[[50]]See Benjamin, “Theses on the Philosophy of History,” trans. Dennis Redmond, available online at: http://www.marxists.org/reference/archive/benjamin/1940/history.htm[[50]] The relevance of the teacher corresponds to the needs of his students. Lacan is only relevant here and now, much more so than Nietzsche. Romantic appraisals of the 19th century are a reflective medium that allows you to go back to the Dionysian days of ancient hedonism, the romantic imagination flitting from one scene to the other faster than you can say desire desires desire: a Lacanian maxim, without which Nietzsche — too late, but still too early — came to psychological ruin. Although, to be fair, there goes romanticism again: the temptation to see Nietzsche’s mental collapse and ‘final’ madness as anything but a case of syphilis.

Stuck between Marx and Freud, Nietzsche is most untimely. Despite this fact, part of the Cause Lacanienne is his redemption and resurrection by a fulfillment of his prophecy about the development of The Grand Style. Nietzsche described his vision with the following words: “Power which needs no further demonstration, which scorns to please, which answers unwillingly, which has no sense of any witness near it, which is without consciousness that there is opposition to it, which reposes in itself, fatalistic, a law among laws: that is what speaks of itself as the grand style.”{{51}}[[51]]Nietzsche, The Twilight of the Idols, trans. Thomas Common (Mineola, NY: Dover Publications Inc., 2004), p. 45.[[51]]

This is not a description of Nietzsche’s own writing style; rather it is a prophecy that has come of age in the works and seminars of Lacan. Here the reader is privy to a style that ‘speaks to itself’ (remember how Hegel described the dialectic as “objective reason talking with itself,”{{52}}[[52]]Hegel, “A. Plato,” Lectures on the History of Philosophy, available online at: http://www.marxists.org/reference/archive/hegel/works/hp/hpplato.htm[[52]] in other words a dialogue without characters or setting, but no shortage of voices?), not in the sense of constructing for oneself a play-park of private meaning (like Derrida does), but in allowing the power of language itself to generate the thought-forms that naturally give rise to a train of association that, for the subject, can take on an antagonistic character in its very spontaneity (insofar as talking to yourself is, at the same time, talking to someone else, an other). Instead of letting this hamper him, Lacan harnesses the objective play of the signifier as the careful contributions made by the Big Other, and adapts these gifts to the flow of his output. The way the ball (mis)bounces is a vital part of style, like an early Louis Armstrong trumpet solo, or the way Neil Young would record his mistakes into the mix.

Mis-style, thus, in our age, is the precondition of the grand style: which is not to say that mistakes are all it takes, but that what goes without them is suspect. Art must now be all and nothing at once; a competition of tongues fused into a monster of speech; a permanent cultural revolution; force that is beyond control and unencumbered, even turning cancerous, explosive, like the horrific transubstantiation of Tetsuo from the classic anime Akira (1988). This capacity for mad growth into something that exceeds proportions, like the breathing furniture from the films of David Cronenberg,{{53}}[[53]]For example, see Videodrome (1983) and Naked Lunch (1991).[[53]] is at home with us in the present. And our depictions of it, in the imagistic content of artistic productions, must also be met accordingly in the realm of letters, to keep honest Hegel’s assertion that language, textuality, is “the most spiritual existence of the spiritual,”{{54}}[[54]]See G.W.F. Hegel, Elements of the Philosophy of Right, ed. Allen W. Wood, trans. H. B. Nisbet (New York: Cambridge University Press, 1991), p. 204.[[54]] i.e. the Super-Spiritual substance, or God-in-the-world It-self. Hence we argue on behalf of “the supremacy of the Signifier,”{{55}}[[55]]See Lacan, “The Direction of the Treatment and the Principles of Its Power,” Écrits: A Selection, p. 359.[[55]] a phrase first offered by Lacan and located at the top of the analytical index for his Écrits, as an appeal to establish it in the minds of readers as the first rule of his guided tour for the perplexed of the present.

Still, Nietzsche and Lacan are united in the ferocity of their polemic. The former hates the entire world, while the latter hates the world so much more that, instead of (ineffectively) blaming everything all at the same time, he focuses his intense scorn on a specific group of bad psychoanalysts who sell short the teaching of Freud. Nietzsche’s macrocosmic rejection and denial of the world, which becomes the inverse basis for his joyous affirmation of life, is replaced by the prestige micro-politics of the International Psychoanalytic Association and its internecine squabbling. However, since so much does indeed depend on the reading and understanding and interpreting of Freud’s teaching, Lacan is to be thanked for adopting such a militant, “asshole”-ish identity over this disputed question: Whither Freud, in today’s era of pharmacopious drug-use, cybernetic reprogramming of ‘thought-forms,’ and hyper-sexed impotence? Who is teaching Freud today, when everything stands for it, nothing against, and yet still, no one does it?

The moral law should be rendered “Read Freud,” if only to get people to understand the multitude of problems that follow from a naive (Kantian) belief in morality, which tends to be found today in low-grade facsimiles of the categorical imperative.{{56}}[[56]]According to Kant, the moral law is: “act only in accordance with that maxim through which you can at the same time will that it become a universal law.” See “Groundwork of the Metaphysics of Morals,” Practical Philosophy, ed. Mary J. Gregor (New York: Cambridge University Press, 1996), p. 73.[[56]] For the first time in history, the question of Desire is posed – not in-itself but for-itself, as a self-recognizing, self-relating entity. For what is desire but the reward attached to the drive that turns the wheel of the world? And surplus-desire but the fantasy to cut class, to ‘get away from it all,’ to leave the cockpit from Rivera’s Man at the Crossroads without a pilot? The demand for research into desire is, in turn, the call for a burning desire to research, to seize the night with upturned telescopes and bottomburned candles.

A curriculum which aims to compliment Freud with Nietzsche – perhaps alongside others favourites such as Sophocles, Kant, Schopenhauer, Poe, etc. – might stand a chance at reviving what Lacan dubbed the Cause Freudienne, in the winter of our society’s anti-Freudian discontent. But we should take this open call for submissions, not to mean a return to the specific organization which went by this name, but rather the psychoanalytic movement itself, the spirit of 1895, the “project for a scientific psychology,”{{57}}[[57]]Over the course of his seminars, Lacan repeatedly alludes to the importance of this document of Freud’s from 1895, which gives a prototype sketch of the way that Freud’s thought would develop along materialist, neurological and physiological, lines.[[57]] that takes science in the dialectic sense of the word. This may add up to no more than what Alain Badiou already suggested, when he claimed that “Lacan is the Lenin of Psychoanalysis,” a relation which casts Freud as Marx,{{58}}[[58]]See Peter Hallward, Badiou: A Subject to Truth (Minneapolis, MN: University of Minnesota Press, 2003), p. 353.[[58]] and also: “Lacan is a condition of the renaissance of philosophy. A philosophy is possible today only if it is compatible with Lacan.”{{59}}[[59]]See Žižek, Less Than Nothing, p. 18.[[59]] In other words, Freud, or at the very least “Freud’s teaching,” as the teaching of Lacan, is our starting point today, even if this means that we are burdened to go back to what is inscribed in the texts and lectures of father Sigmund, rest his soul, before we can begin to make heads or tails of the Lacanian voodoo.

But Lacan, as the first one to relay a radical interpretation of Freud that went fearlessly to the root of his teaching, can nonetheless be said to add something totally original to the progression of the psychoanalytic Idea. This very erection of the name of Freud to the rank of King-Master, for Lacan, becomes a way of getting the obvious out of the way and dealing with the elephant in the room, in order to get down to business, to the work of philosophy, to a teaching of dialectics that accepts Freud’s contributions to the materialist conception of the human body and the nature of psychosexual development.{{60}}[[60]]See Freud, Three Essays on Sexuality (1905).[[60]] In the same way that Žižek belts us over the head, repeatedly, with the imperatives to “read Hegel” and “read Lacan,” shamelessly promoting the status of these figures like a fan-boy, Lacan’s constant boosting of Freud qua Freud (as opposed to Freud qua Anna, Brill, Strachey, Jones, Klein, Horney, Adler, Reich, Jung, etc. etc.) is a way of being able to develop the plot, while at the same time bringing up to speed those who tuned in late to the broadcast, and as a consequence have yet to locate the villains in the story.

Which brings us back to the present, not so much for resolution as to recap: without acknowledging our foundations in the dialectic (of Hegel, Marx) and Lacan’s interpretation of Freudian psychoanalysis (with Lacan himself as the self-relating, ‘doubled’ negativity that lets him stand for Freud qua Freud as well, as the radicalization of Freud), it is impossible to begin to reckon the full extent to which Nietzsche fits into our (post)modern moment. What Lacan et al., when taken as such, can show us about a one like Nietzsche, is that his very disjointed, out-of-place aspect is, at the same time, his most proper and fitting place, insofar as this replicates his position as the primordial father of the modern mind, which had to wait to be recognized officially as a Freudian creation, in order to come into conscious knowing.

As a result, Nietzsche, his own prophet, is left to bury himself. A tragic climax to a murder-suicide, which claimed the life of One God and the last man. And while Nietzsche is dead, gone for good, at least with Lacan we can learn how non-all is not lost. A new society is on the horizon and with it the creation of a new man and women. The grand style and its multiplex variations leads the way, like a Piper at the Gates of Dawn whose song is free jazz, whose style is form unleashed, revolutionized. For until structures walk the streets once more as they did in ’68,{{61}}[[61]]See Žižek, Living in the End Times (London: Verso, 2010), p. 353.[[61]] there is no hope and no potential for social renewal or cultural rebirth. Just as without the reconstitution of the subject, there is no possibility of recovery. And without an organized operation to reap the grapes and ferment the wine, what’s ripe will turn rotten, left to wither on the vine.

—Noah R. Gataveckas

.

Noah R. Gataveckas is a writer and educator who lives and works in Toronto. He is currently working on a book called Symposium: A Philosophical Mash-up, a portion of which can be found here on Numéro Cinq (see “Professor O’Blivion Rides Again“). He has also written numerous articles, one play for performance (“Five Star”), and a manifesto (“Why do we burn book?; or, The Burning Question of Our Movement“) also published on NC. See the June issue of the Platypus Review for his essay: “La contra Adorno: The Sex-Economic Problem of Platypus.”

.

.