Sydney Lea with Cora, his granddaughter

Sydney Lea with Cora, his granddaughter

Let’s not mince words. Sydney Lea is a masterful, passionate, eloquent writer, just getting better with age. He can do about anything he wants with a sentence, corral any emotion, evoke mystery, rail, weep, mourn, confess, ponder, berate, and rejoice. He works in image and memory with an audacity that is breathtaking, all the more so because it seems both effortless and utterly in control. His essays read like long complex sentences, surging forward, splitting and converging and splitting and converging, incomplete until the last period after the last word, when, as Yeats is supposed to have said, they snap shut with the click of a well-made box. I won’t say more. The middle essay will break you heart.

dg

.

The Serpent on Barnet Knoll

The young retriever noses a frozen snake across the rain-glazed snow. The creature should long since have wriggled deep into mulch in some granite fissure, so that when it died, it would do so down there, in secret. That it didn’t seems odd.

But my mind’s still odder, having followed its own inward paths from that coiled corpse to a moment this morning before I set out: at the mirror, greasing lips against the cold, I inspected myself. The age-lines, the puckering mouth, the thin gray hair—all still surprised me. I also studied a wen, the permanent swelling that puffs my left eyebrow into a small horn. It’s the frozen snake that has reminded me of that passing moment, though how it did so I can’t explain.

Out here, I encounter the morning’s savage gusts. The spruce-tops thrash and complain. When there’s a lull, I hear the ceaseless and meaningless scolding of red squirrels, the grating of ravens.

One day, in my third grade year to be precise, I knocked off Joe Morey’s hat on the playground, taunting him for a sissy, even though he and I were friends for the most part. Nearly weeping with frustration, he reached down for the hat at the same time I did. Our heads clapped together, my brow swelling slightly but, as it turned out, forever. I’d meant to be cruel that day, I was, and I got my long-lasting due.

In life, the snake was a mere, harmless garter. Today it’s something else, and makes me quit my hike for a while. I stand and wait, but nothing comes to change me. Why would I dream it would, no matter my unvoiced, uncertainly directed, all but unconscious pleading?

It’s almost Christmas, a holy time for many. Through decades of northern winters, I’ve never seen a snake at large in December. But however I strive to discover something significant in the event, nothing reveals itself except what I’ve long known about snakes—mere facts, devoid of meaning, versions of reality that seem only somehow to discredit me.

Was this the creature’s first cold season? Who knows? A snake doesn’t count or reason. But I do; I know there are just so many moments in anybody’s life. Why do I stand here statue-still and fritter a single one away? And yet what else should I be thinking about?

I have wife, children, grandchildren, along with a host of lesser earthly attachments. I clench them tight to my heart, but there come times when a sort of unattached self prevails. Left at large too, I know, that other self might contemplate violence or crime. Also, of course, it doesn’t. I daily, dutifully, and gladly return to a bourgeois life. Am I not therefore absolved? But what in me requires absolution anyhow? I simply feel this unsettledness, ungovernable, random, opaque.

One day my head struck a temporary enemy’s head, but even before that, surely, something had slithered into my soul. It would linger lifelong, making subsequent, unwelcome forays up to the cool surface, whenever, however it might.

.

–

Catch

Whoever you may be, stop reading now if too much sentiment, no matter how genuine, makes you uneasy or angry or whatever else. If you do hear me out, however, I hope you’re not the sort who’d say that my good wife throws like a girl, as my Little League baseball coach once claimed I did, the moron. I threw just fine until my arm got robbed by age. That happened some time back, to be sure.

You don’t have to remind me I might have known worse losses.

Whoever you are, go stand beside my wife, at exactly sixty feet, six inches from some target, and then by God we’ll see how many times she can take a ball or even a stone and hurl it, and how often she’ll hit the can, the post, the tree– and then we’ll see how often you do. Good luck, sucker.

No, wait a minute. There’s little reason to start all this in anger at you, whom I probably don’t even know. I won’t pretend I’m not angry, but why lash out at a stranger? It’s doubtless only despondency that makes me talk this way.

I’ve now and then pictured my wife playing catch with the one boy in her five-sibling family, the one who fought cancer for twelve years and died this past December. I loved him, which is no doubt a crucial factor in my behavior here, my rhetoric.

I’ve seen photographs of those two kids, gloves on left hands, half-smiling, squinting under a summer sun, decades and decades ago. They were a good-looking pair in those days, and both were handsome into late adulthood, no matter most of his hair had been robbed by the vile, stinking chemo, and some of his teeth.

My wife recalls how, in the warm months, when they got home from school, the two would head right out to their yard to toss the baseball around and chat away the afternoon. For me, that’s the very picture of innocence and affection, and if you, anonymous you, consider it the stuff of Norman Rockwell or Hallmark, just haul your sorry self off.

There I go. Forgive me. I’m just uncertain which emotion is which here. For all I can really say, you were innocent too, and still may be, or at least known as a decent, caring person, and it’s not after all as if I have some corner on innocence myself. Sometimes I reckon I’ve never been any better than I have to be.

For one thing, I probably should have been paying closer attention to my wife’s brother—and to my wife as well, come to think about it. Not that it does anyone a bit of good when I beat myself over the head for my omissions. That doesn’t change a thing. If it could, I’d keep at it forever, as in some respects I suppose I have.

On those long-gone afternoons, my wife learned to throw like a man. Instead of moping and cursing, I wish I were man enough to report all this and not break down. But do I really? Do I want to be manly by that definition—furious, fearless, unwilling to take any quarter or give any? There are better things to wish for. I know that these days.

My brother-in-law and I used to go down and watch our Red Sox play at Fenway Park. After a while we had daughters and sons, and we’d take them along. Home runs, triples, double plays: we roared approval at these and more; but we all, child and grownup alike, especially loved those bullet throws that Dwight Evans delivered to cut runs off at the plate.

Too soon, it seems, our lives just seemed to get too busy for Fenway. Then the god-awful cancer showed up. Starting in my brother-in-law’s colon, it got to traveling elsewhere afterwards, and the whole time I only sat here and typed words, as I’m doing even now, weeping. Meanwhile my poor wife is sick with sadness, and I wouldn’t blame her if, thinking back to those old summers, she picked up something and threw it dead-center between God’s eyes.

.

–

The Couple at the Free Pile

Autumn’s church bazaar is over, all the stalwart, weathered tents of the vendors struck except the one over the White Elephant table. Early this Sunday morning, such tatty wares as went unsold still sprawl on the plastic tablecloth or on the ground, but the sign up front reads FREE.

No car approaching or following, I brake to a crawl so I can observe a man and woman making their deliberate ways through the jumble. I naturally notice that their goods are gathered in the rusted bed of the wheelbarrow my wife and I donated to the event, which nods on its fat, limp tire like a weary draft animal.

For me to stop completely might be to embarrass this couple, who covet what we congregants had considered encumbrances. And yet, however it shames me, my curiosity—like desperate thirst, or lust—also impels me. I’ll drive on, circle the village common, and pass back this way again from the other direction. After all, the two scavengers seem devoted to their scrutinies; I doubt they’ll notice my second inspection.

I turn by a picket fence enclosing a big house’s tidy lawn at the south end of the common. The owners held a well-attended garden tour there last June. Then I swing right again, north, going by the famous corner elm, which residents agreed at town meeting to save, approving a line item that funded the tree surgeons’ services.

During the festival, I visited the White Elephant booth myself. As the saying goes, one man’s trash is another man’s treasure, and you never know. As I predicted, however, nothing appealed. Among other bits of uselessness, say, I found a basketball so worn it had lost all traces of its original, pebbled orange; three recumbent, saucer-eyed ceramic deer; a few chipped plates, inscribed Disneyland, 1974 and showing portraits of Mickey, Goofy, Donald; raveled rugs; tarnished lampshades and sconces. So on.

Passing the elementary school, I make a right again, and, before the turn that will take me to another view, I stop at the intersection, just opposite the village store. My wife and I will be having lunch there in an hour or so. Its deli is the best-stocked one for miles, the staff all cheerful.

As I drive, even more slowly than before, past the White Elephant display, I see a car seat in a Bondo’d pickup’s cab. It holds a child, and he or she—it’s hard to tell through the windows’ grime—must have been sleeping a few minutes ago, but now I can just make out a mouth, gaped in a yowl I can’t hear, even if I can imagine it. Surely one of the parents, or both, will step out of the tent to tend the toddler. For now, though, they stand motionless, one on either side of the wheelbarrow, eyes on me. Their stares are furious.

—Sydney Lea

.

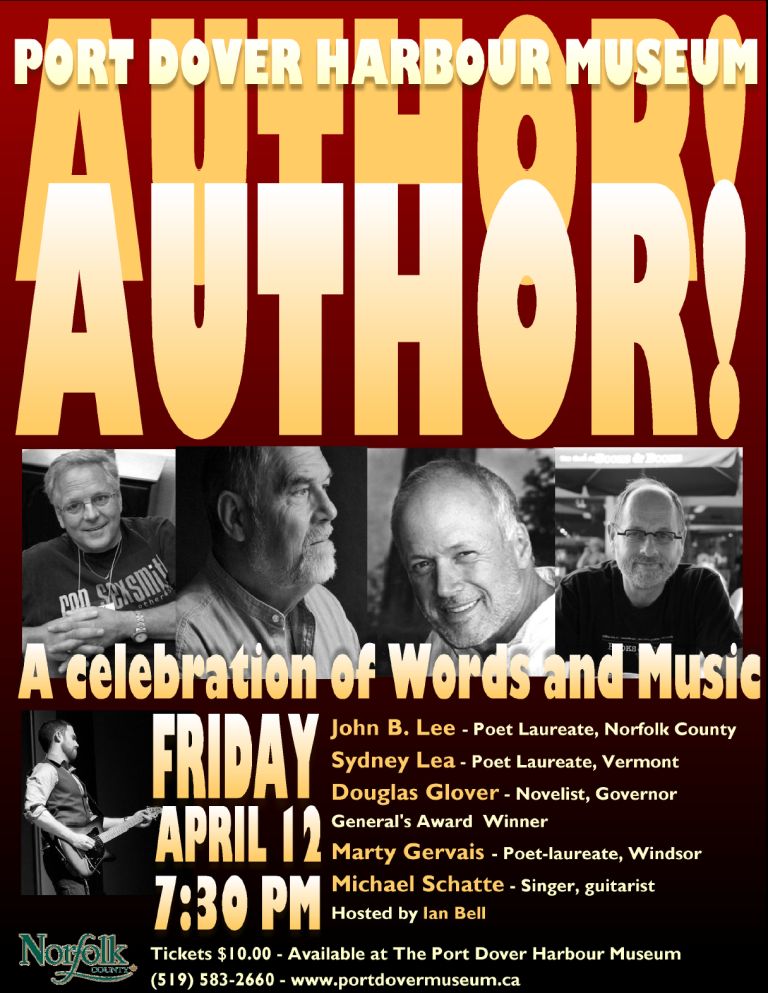

Sydney Lea is Poet Laureate of Vermont. He founded New England Review in 1977 and edited it till 1989. His poetry collection Pursuit of a Wound (University of Illinois Press, 2000) was one of three finalists for the Pulitzer Prize for poetry. Another collection, To the Bone: New and Selected Poems, was co-winner of the 1998 Poets’ Prize. In 1989, Lea also published the novel A Place in Mind with Scribner. His 1994 collection of naturalist essays, Hunting the Whole Way Home, was re-issued in paper by the Lyons Press in 2003. Lea has received fellowships from the Rockefeller, Fulbright and Guggenheim Foundations, and has taught at Dartmouth, Yale, Wesleyan, Vermont College of Fine Arts and Middlebury College, as well as at Franklin College in Switzerland and the National Hungarian University in Budapest. His stories, poems, essays and criticism have appeared in The New Yorker, The Atlantic, The New Republic, The New York Times, Sports Illustrated and many other periodicals, as well as in more than forty anthologies. His selection of literary essays, A Hundred Himalayas, was published by the University of Michigan Press in September, and Skyhorse Publications just released A North Country Life: Tales of Woodsmen, Waters and Wildlife. His eleventh poetry collection, I Was Thinking of Beauty, was published in 2013 by Four Way Books.

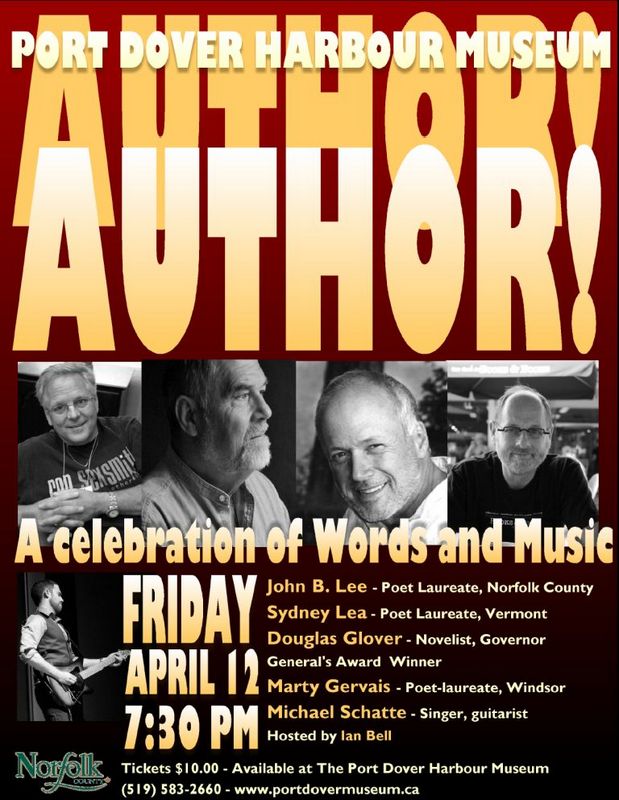

Douglas Glover, photo by Danielle Schaub

Douglas Glover, photo by Danielle Schaub Sydney Lea

Sydney Lea John B. Lee

John B. Lee Marty Gervais

Marty Gervais Michael Schatte

Michael Schatte