.

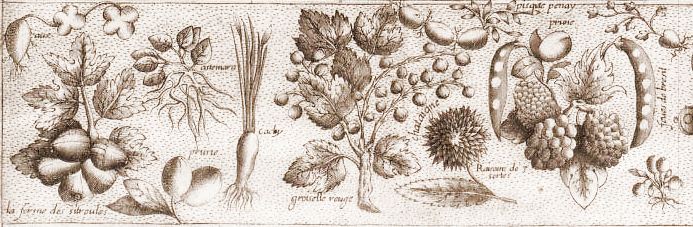

This poem in Alexandrine verses was written by a Parisian lawyer, Marc Lescarbot, who had joined the early French settlement at Port-Royal, near present-day Annapolis Royal on the Annapolis Basin of the Bay of Fundy in Nova Scotia. After a year of active engagement in its development he was obliged to leave again in July 1607, at which time he composed this extraordinary description of the country’s resources as an inducement for continued investment in the venture he so ardently supported. The reason for his departure and the abandonment of Port-Royal was the financial difficulty of Pierre du Gua, Sieur De Monts, and his associates, whose monopoly on the fur trade had been abruptly canceled by the King of France, Henry IV. The poem appears in a collection of similar occasional verse entitled Les Muses de la Nouvelle-France that was added to Lescarbot’s Histoire de la Nouvelle-France, written after his return to France. The writing of the poem was started just before departing the Port-Royal and continued at sea. It is, in effect, the first extensive poetic description of Canada. Whilst there are translations of the Histoire, I have yet to discover an English translation of this poem. The text of this translation is based on the third edition of the Histoire de la Nouvelle-France of 1617, published electronically in 2007 by the Gutenberg Project at www.gutenberg and produced by Rénald Lévesque.

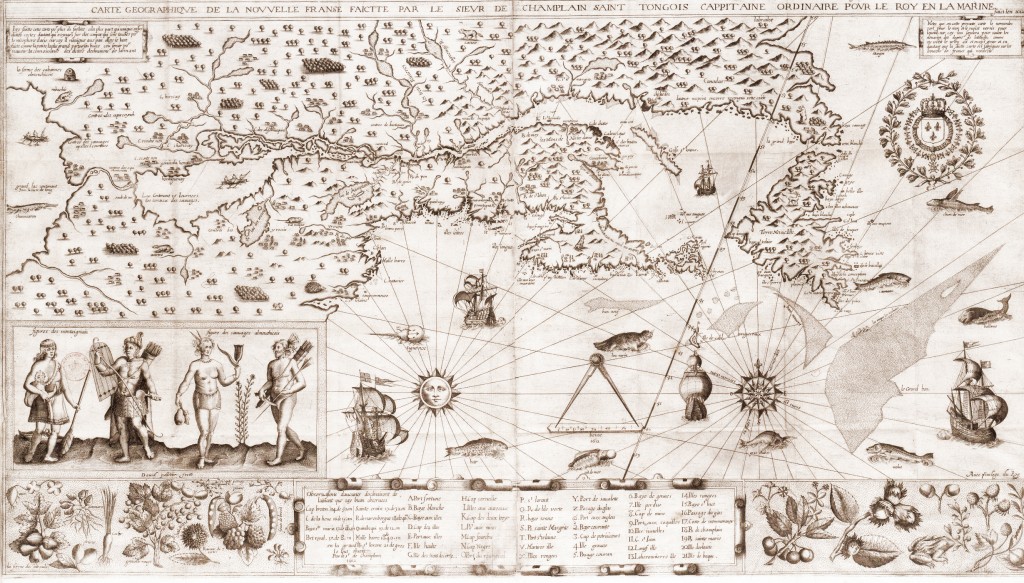

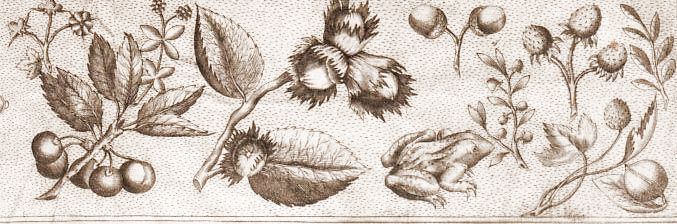

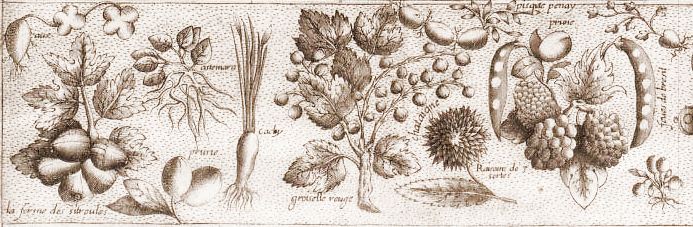

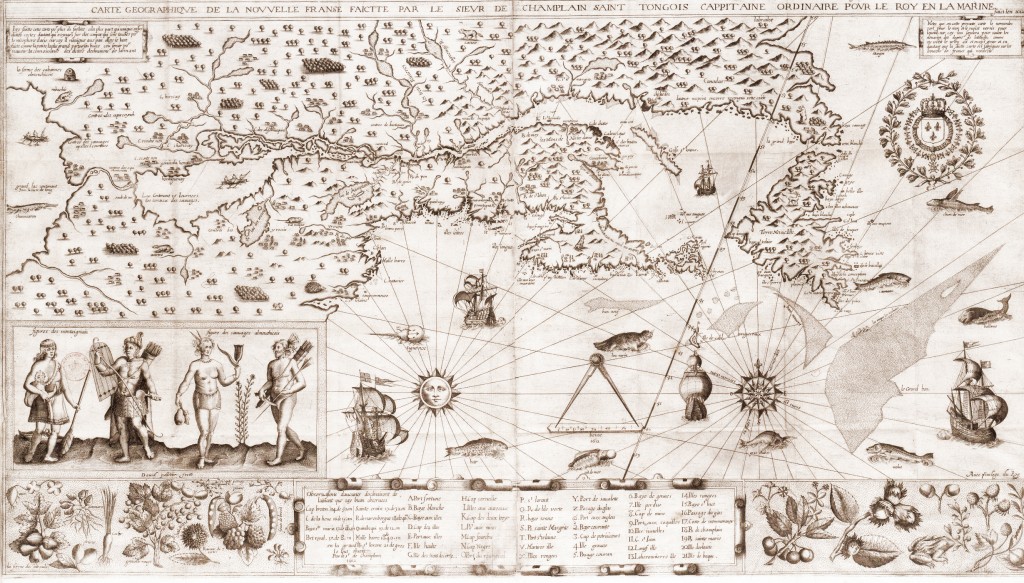

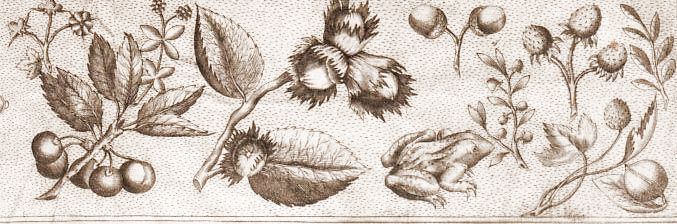

Detail from Champlain map, Nova Scotia, Bay of Fundy, etc.

Detail from Champlain map, Nova Scotia, Bay of Fundy, etc.

Why did Lescarbot decide to go overseas in the first place? The reason he gives for wanting to go to New-France is a set-back he suffered as a lawyer in court due to a corrupt judge. He was, therefore, personally predisposed to find a better, uncorrupted world.

The start of the poem (1-12) is highly rhetorical and polemical, with an expression of Lescarbot’s personal regret at having to leave this beautiful place (1, cf. 25, 33, 47, 59) and three indignant rhetorical questions intended to shame his compatriots for their lack of constancy in abandoning the new settlement and the investment and efforts already expended, as well as chiding them for their dishonorable failure in establishing a new province of France (2-12), combining personal, aesthetic, moral, economic, patriotic and imperial motives. The polemical element is raised to the highest level later on, when Lescarbot reminds the King of his duty as a Christian monarch to spread the faith (167-176); he even questions the Lord God directly as to why he left the Native peoples out of his divine plan (293-304). These are themes of the highest order in literature, the duty of Kings and the ways of God to man, typically treated in epic and drama, but here combined with the profit motive. Significantly, the religious mission of the King is linked directly to the bounty of the land specifically created by God, he maintains, to motivate the King and to attract the French to the exploitation of its resources (177-180), thus connecting commerce with the spread of the Christian faith. Moreover, Lescarbot expresses regret that his intended audience, i.e. the French generally but specifically present and potential investors, do not know the attractions of the country (13-16). The actual phrase used in line 14, the “attractive lures”, serves to whet the appetite by introducing the lure of profit to be gained from the exploitation of its resources. Admittedly, these investors had just suffered a great loss due to a Fleming (Flamen = Flamand, 15), who had acquired furs along the St. Lawrence ahead of the French and robbed theirs as well, along with their canon. Lescarbot suggests that the investors will make good on their losses with compound interest (usure, 16). These are the addressees referred as vous in lines 9, 10 and 13, whereas nous in lines 3, 5, and 7 refer to the French collectively, with all of them being accused of a lack of steadfastness (3).

After this highly charged opening aimed at the main addressees of the poem, and following a prayer for safe passage back to France that emphasises the danger of the journey and the physical as well as spiritual distance of the “new peoples”(19-24), Lescarbot launches into a description detailing all the attractive and productive features of Port-Royal and its topography: a secure harbour, protected on both sides by hills and mountains (25-26), alluvial flats along the shoreline providing grazing for the plentiful game (27-30), and springs and streams making for well-watered valleys (31-32), with plenty of rain mentioned later(351-354). The emphasis on the presence of water is significant, suggesting a frame of reference based on the Mediterranean, with a climate perennially short of sufficient moisture in summer. Significant also is the mention of an unnamed island hyperbolically said to be worthy of the greatest king on earth (54-55) and whose commanding role is foreseen through an epic simile (37-41) in that its elevated headland dominates the surrounding plain, again a Mediterranean and, more generally, European ideal for the location of a fortified city or citadel. This city is ready to be built from the rocks supplied by the sea shore (43-44). Lescarbot introduces here (53-56) and throughout a prospective element of development and a potential for growth seen in terms of urbanization and permanent occupation by married settlers (57-58), the physical, economic and social cornerstones of European society.

Next, he invokes the fertility of the place, based on his own experience in developing gardens and working the fields at Port-Royal (61-62). Working the soil seems to have endeared the country to him as well as giving him a sense of –collective- ownership. It is also rather unique for an early visitor-explorer to have actually mixed his sweat with the soil in this way to test its fertility. At the same time, there is an idyllic element in the description (47-52) of a lovely little stream amidst the young greenery of a little valley in the hollow of the island’s bosom to which he “has lent his side” many times because of its beauty. This is a gratuitous detail that escapes the preoccupation with turning nature into culture: it introduces, not just the literary commonplace of the locus amoenus, or plaisance, ultimately based on the description of the Vale of Tempe in ancient Greece, but also a personal and, in fact, sensuous experience. Lescarbot’s originality in this has been noted by the critics. Paolo Carile has pointed out that, whereas in Champlain, beauty of nature is identified with utility, in Lescarbot the natural environment is estheticised from personal experience. He notes other literary innovations as well. The Farewell poem was a known genre restricted to a sentimental good-bye to a woman loved: in Lescarbot’s version, the object of desire changes to a colony in North America, here personified by the lovely island. Similarly, regret at leaving a place is a known literary theme, usually combined with praise of its various features; Lescarbot extends this to the resources of the country and the profit to be gained from them. The new context, colonialism and mercantile capitalism, occasioned a novel and hybrid genre along with a new purpose. In terms of point of view, we may add here the novelty of a poetic eyewitness account based on first-hand experience, rather than an imaginary description of the New World with many fantastic features as we have them in earlier literature. The systematic observation of flora, fauna, and the four seasons, adds a scientific element.

After mentioning the products of nature that grow spontaneously (65-66) he starts his elaborate praise (los= laus in Latin, 63) of the natural resources with a catalogue of the countless types of fish providing nourishment in Spring (73-106), including well-known varieties such as herring (77-79), so plentiful, it alone could make a people rich (78) and, of course, cod, so abundant that it is said to provide sustenance for almost the entire universe (101-108). In all, 27 types are mentioned but there are a thousand more unknown varieties (99). Lescarbot’s catalogues have been linked by past commentators with the Natural History of Pliny the Elder and, more generally, with the encyclopedic tradition of Antiquity, Middle Ages and the Renaissance, with the enumeration of curiosities found in travel narratives, and with the scientific poets of the 16th Century. The catalogues can also be linked to Adam’s naming of God’s creatures (Gen. 2.19) as a form of appropriation, of taking possession of the earth and having dominion “over the fish of the sea and the birds of the air”(Gen. 1. 26, 28). I would like to suggest yet another connection. We are now solidly in the territory of hyperbole and idealisation, recurring stylistic features that elevate this potentially pedestrian description of resources into the realm of the epic paragon or nul-pareil, ultimately serving the promotional purpose of the poem. The association with the epic is suggested as well by Lescarbot’s use of Alexandrine verse which is typically associated with elevated diction and grand and dramatic themes. The poet chose the same verse form for his heroicising account of the raid of the Micmac chief Membertou against the Armouchiquois across the Bay of Fundy also found in Les Muses de la Nouvelle-France.

All the desirable natural wealth enumerated here will make the future settler of this other (promised) land more blessed with a miraculous food supply than the manna of the Hebrews in the desert or the nectar of the blessed spirits of Greek myth (106-12). Throughout, Lescarbot easily mixes mythologies, pagan with Christian, as in lines 167-172 where he invokes the eagles of Jupiter to bring the decree of the King of Kings to the French Monarch, commanding him to spread the Christian faith. God’s omnipotence is demonstrated by the presence of the biggest sea creature of all, the whale (113-119) that comes into the bay daily. Winter provides shellfish, giving nourishment even to the poor and the improvident (125-128), as well as an opportunity for hunting large game and fur-bearing animals, especially the beaver, whose dens Lescarbot finds a thousand times more admirable in their construction than European palaces (135-140). It is remarkable, though, that Lescarbot does not make more of the fur trade at this point. It was the most profitable enterprise, but also the most contentious and problematic because of the competition from the English and the Dutch as well as the opposition from other French merchants to the monopoly of De Monts and his associates. In the final analysis, Lescarbot personally preferred agriculture over trade. This is followed by a catalogue of 37 birds (184-232), including a description of the previously unknown humming bird, seen as another example of God’s omnipotence in creating the smallest bird of all (205-232).

It is not only in his creatures that Lescarbot sees the hand of God. The very bounty of nature and its pleasures have been created by God to attract the French to this land where their labours will be rewarded in proportion to their desires (177-180), in order to propagate the faith which, moreover, is the God-given duty of the French King (173-176). Colonisation is ultimately justified by the religious imperative. Lescarbot himself gave religious instruction on Sundays to le petit peuple, the French workers and artisans of the colony; the leader of the colony, Poutrincourt, likewise instructed the Micmac (305-310). Autumn brings the harvest of the fields and gardens, in particular corn (blé d’Inde) that grows to prodigious heights (251-256), a harvest Lescarbot regrets not seeing because of his premature departure (257-266). Surprisingly, the climate is said to be not as cold as that of NW Europe (269-274), mainly because Lescarbot happened to experience only one mild winter (no snow until December 31, 1606 which promptly melted, and continuous snow cover only in February) and because of the varied impact of the Little Ice Age which saw the river Thames frozen over during the winter of 1607. Incidentally, there is a detailed and delightful recent description of the seasons on Annapolis Basin by Harold Horwood, a Newfoundlander who took up residence there and who mentions surprisingly mild winters, entitled Dancing on the Shore.

After this elaborate praise of the natural resources and the proven potential for agriculture, Lescarbot turns to the native inhabitants, the Micmac, whom he presents as in many respects superior to the French morally (329-340), while asserting their common humanity (297-298). He also makes an argument based on cultural relativism comparing the culture of the native population with that of nations of antiquity elaborated in Bk. 6 of his Histoire de la Nouvelle-France, entitled “Description des Moeurs Souriquoises Comparées A Celles d’Autres Peuples” (M.-C Pioffet, Marc Lescarbot: Voyages 2007, pp. 241-471) and comparing Micmac hospitality with that of the ancestors of the French themselves, the Gaulois. (321-322, 339-340). This comparative approach and the implicit transfer of the prestige of antiquity culminate in the work of the Jesuit Lafitau comparing the Iroquois with the early Greeks, Romans and Hebrews. Lescarbot’s cultural relativism even extends to language when he chooses to retain a Micmac word rather than imposing a “foreign” French name on a creature unknown to him (223-224). And he actually makes the now familiar ethnological distinction between hunter-gatherers and (semi-)sedentary cultivators of the earth, while privileging the latter way of life, as all Europeans did (285-290). The only respect in which their condition is deplorable is the fact that they lack the faith which –he maintains- they are eager to receive (291-314, cf. 166; by contrast, the first Jesuit missionary, Pierre Biard, relates a few years later that the Micmac listened to him politely but did not change their views one iota. The native people he has come into contact with (321-328), in particular the Micmac, are “subtle,” skillful or intelligent, possess good judgement, and are not lacking in understanding (321-324). They only require a “father” to teach them to cultivate the earth and the vine, and to live civilly in permanent habitations(321-328; cf. 287-290), thus combining paternalism with agriculture, viticulture and urbanism, the basis of Mediterranean culture. The main vice that he attributes to them is the desire for vengeance (341-342), a vice actually shared by the poet himself (390-393), and he criticises them for being improvident when it comes to securing an adequate food supply (125-131; 327). Clearly, the hunter-gathers’ apparent pattern of feast or famine appears to him as a moral failing: Lafontaine’s fable of the ant and the cricket comes to mind here. Overall Lescarbot’s presentation reflects, on the one hand, Montaigne’s notion of the bon sauvage unspoilt by civilisation, and, on the other, the largely positive first encounter between the French and the Micmac. It also serves the promotional discourse by stressing the duty of the French king and higher clergy to introduce the faith to these model catechumens. In fact, Lescarbot sees conversion not as a side benefit of colonisation; rather, the prospective harvest of souls is the ultimate goal (162-166), supported by the mercantile venture and the country’s resources. His religious and utopian motives, focused on an agricultural community of French settlers flanked by Native agriculturalists (287-290), become increasingly evident through sheer repetition as the poem progresses ( 59-64; 181-183; 251-264; 287-290; 321-329; 396-411), culminating at its conclusion in lines 423-426.

Significantly, mineral resources are only introduced briefly toward the end of the poem (385-388). Clearly none of these had been developed (Lescarbot speaks of nurseries or breeding grounds of mines, 385) and the poet only gives a sketchy account of them, mentioning bronze (actually an alloy as he probably meant copper), iron, steel (a man-made product) and silver as well as coal. In an earlier farewell poem, he still expresses the hope that silver and gold will be discovered (Adieu aux François, August 25, 1606), the two most desirable get-rich- quick minerals universally sought after by European rulers and their explorers in the Americas. In the original charter issued by Henry IV in 1603, De Monts was specifically charged to bring home any gold and silver. Clearly, Lescarbot has given up on this prospect, hence the emphasis on agricultural produce and the potential for settlement of French colonists. As if to compensate, he does add, at the very end (412-422), almost as an afterthought, a luxury product, the high quality “silk” worthy of kings and produced by local hemp which could lead to a textile industry manned by Native(?) workers who have chosen to become sedentary.

On balance we can assume that French investors would not have been impressed by this prospectus that mainly emphasises agriculture and settlement. The cod fishery was already established in Newfoundland waters, a location much closer to Europe, and De Monts’ monopoly on the fur trade had been cancelled by the King, although a final one-year extension was granted after the colonists’ return. Lescarbot must have sensed the weakness of his case as he finished his poem by extolling, in compensation, the moral superiority of agriculture as a pure, untroubled way of life far from poverty, the madding crowd of his French homeland, and its deceit (423-426), possibly reflecting his own motives for leaving France in the first place and recalling the idealisation of the simple farmer by the Roman poet Virgil. And the “victory” attributed by Lescarbot to De Monts (363-384) is therefore only a moral victory to compensate for the failure of the enterprise as well as its disastrous first winter on the Ile de Sainte-Croix off the coast of New Brunswick, saluted by Lescarbot in passing on his return journey (363-384).

The Church did not rush in either to fund missionaries. The first Jesuit missionary, Pierre Biard, had to wait for years before he could sail for Port-Royal in 1611, not until a private sponsor was found in the Marquise de Guercheville, who raised funds through a subscription and had to buy into the commercial enterprise in order to secure passage for Biard and his companion, Énemond Massé. She actually had to buy out the two Huguenot merchants from Dieppe who were unwilling to take the two Jesuits on board; similarly Maria de Medici, the widow of the late King Henry, assisted financially in bringing about this first Jesuit mission to Canada. However, financial support was to remain problematic. The actual practice of supporting the missionary activity through profits from the fur trade made the Jesuit missionaries into competitors and led to conflict, in France and in Port-Royal. The whole concept of directly supporting religion through commerce was misguided.

In essence, Lescarbot’s account idealizes Port-Royal, but occasionally, less attractive aspects of the colony do make an appearance: its distance from France (21-22, 381), loneliness (162), the absence of female company (57), the need to improve the agricultural land (249-250), and the dangers of the North Atlantic (6, 21, 358, 380), in particular fog (349-350). Yet, despite these drawbacks, the poem testifies frequently to his profound personal disappointment at its abandonment (1-2, 160-161, 164, 170, 257-264, 344) arising from his own involvement and labour (61-62). The poet is a convert to his own cause. As such, the poem represents a final, almost desperate attempt to “sell” Port-Royal to his fellow Frenchmen by appealing at one and the same time to their financial, patriotic, imperial, as well their esthetic, moral and religious instincts, enhanced by the affective quality of his poetry and carried by the poetic licence of hyperbole in a variety of voices: from lament to praise, and from prayer to adhortation. The purpose is rhetorical, to persuade others of the lawyer’s cause. In terms of genre, we can add polemic, commercial prospectus, natural history and ethnography to the epic and idyllic elements already mentioned. Pioffet and Lachance speak of a “hymn to diversity and abundance” (cf. 106-108, 110-113, 158-159). The modification of the poetic genre of the Adieu from animate to inanimate addressee entails the figure of personification in the direct address of the island (55-57, 61, 109, 111, 158) and of the Earth itself (403-411), suggesting the pronounced symbolic value of the “New World”.

Lescarbot never returned to Canada but his little-known poem marks a unique text in comparison with other French explorers to Canada who all wrote in prose and hence, by definition, are far more prosaic in their ideas and expression, all the more so since they regarded the land purely in terms of its utility, as Carile has pointed out. At the same time, Lescarbot’s text throws into high relief a period of early European colonisation when the motives of imperialism, early mercantile capitalism, religion, and utopian idealism were joined uneasily. What is not unique is the fact that ownership of the land and its resources is not brought up in the poem. Lescarbot does address contemporary criticism of the appropriation of Native land at the end of the chapter “À la France” in the Introduction to the third edition of his Histoire de la Nouvelle-France where he provides the following theological justification: God has created the earth for man to possess; the Natives have not fulfilled this mission; Christians are the privileged children of God and hence, presumably, entitled to take possession. In other words, Native land use is seen as an underutilisation of its resources, creating a God-given opportunity for European colonists. Land and sea are presented as virtually crying out to be exploited. The underlying pattern is one of undervaluing Native culture and overvaluing one’s own claim, along with the local resources, which, even where modest, are presented as fabulous and there for the taking. One is reminded how persistent these attitudes are and how recent the realisation of their consequences.

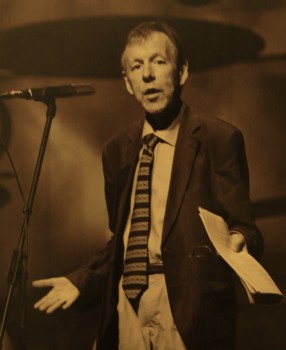

—Haijo Westra

§

NOTES ON THE TRANSLATION

Only a verse translation would do justice to the rapturous tone and persuasive impact of the French original. The prose translation presented here inevitably falls short in these respects but makes available a unique text that offers some surprises in terms of its own conceptions of language, translation, and authenticity. Specifically, Lescarbot makes a point of maintaining the Micmac words of creatures he is unfamiliar with: Poulamou (= tomcod, line 89); Nibachés (raccoon, 155); and Niridau (=hummingbird, l. 223). In the last case he even considers the imposition of a French name to be inauthentic and he is able to conceive of his own language as foreign in this context (223-4). It should be kept in mind that the French names Lescarbot gives to native plants, birds and fishes derive from the other side of the Atlantic and are not necessarily accurate. For example, the laurier (laurel) of line 67 is not native to North America. The Joubar of line 95 is not a fish but the fin(back) whale, according to Ganong. See also Saunders, Speck, and Wallis in Deal’s bibliography for nomenclature. The Rivière de l’Équille (Sand Eel River, 91-92) already had its name changed to Rivière du Dauphin by Champlain; today, it is called Annapolis River. For a running commentary on all matters of translation, see the footnotes to the edition by Pioffet and Lachance.

§

SELECT BIBLIOGRAPHY

Carile, Paolo. Le Regard entravé. Littérature et anthropologie dans les premiers textes sur la Nouvelle-France. Septentrion, Sillery (Québec) 2000, pp. 68-82.

Deal, Michael. “ Paleoethnobotanical Research in the Maritime Provinces.” North Atlantic Archaeology 1 (2008) 1-23.

Ganong, W.F. “The Identity of the Animals and Plants mentioned by the early Voyagers to Eastern Canada and Newfoundland.” Proceedings and Transactions of the Royal Society of Canada, Series 3, vol. 4, section 2 (1909) 197-242.

Lachance, Isabelle. La Rhétorique des origines dans l’Histoire de la Nouvelle-France de Marc Lescarbot. Thèse de Ph.D. Université de McGill 2004.

Pioffet, Marie-Christine and Isabelle Lachance. Marc Lescarbot. Poésies et opuscules sur la Nouvelle-France. Editions Nota Bene 2014, pp. 27-37, 99-120.

Pioffet, Marie-Christine. Marc Lescarbot. Voyages en Acadie (1604-1607) suivis de La Description des moeurs souriquoises compares à celles d’autres peuples. Presses de l’Université Laval, 2007.

§

Detail from Champlain map

Detail from Champlain map

MARC LESCARBOT, A-DIEU A LA NOUVELLE-FRANCE du 30 Juillet 1607/ Farewell to New France, July 30, 1607: English translation

- Must we abandon <all> the beauties of this place

- And bid Port-Royal an eternal farewell?

- Shall we then forever be accused of inconstancy

- In the founding of [a] New France?

- What use is it to us to have borne so many labours

- To have battled the assault of the vexed waves

- If our hope is in vain, and if this province

- Does not bend under the laws of Henry, our Prince?

- What use is it to you to have

- Incurred useless costs, if you take no care

- To harvest the fruit of a long-term expenditure

- And the immortal honour of your patience?

- Ah! How I regret that you do not know

- The attractive lures of this land

- And even though the Fleming has caused you damage,

- Loss is often made good with compound interest.

- So that is why we must leave and get ready <to sail>

- And go to drop anchor in the harbour of Saint-Malo.

.

- FATHER OF THE UNIVERSE, who commands the waves,

- And who can cause the deepest sea to dry up

- Grant us to cross the watery abyss

- By which you have separated all these new<found> peoples

- From those who are baptized, and without shipwreck

- To soon see the shore of France’s Kingdom.

.

- Farewell, thus, beautiful coasts and mountains as well

- Which, with a double rampart, gird this harbor here.

- Farewell grassy glens which Neptune’s flood

- Bathes generously, twice with every moon,

- And to the <wild> game as well, which in order to find pasture

- Comes hither from all sides, there is so much vegetation.

- Farewell my sweet pleasure, springs and brooks

- Which water the valleys and the mountains with your moisture.

- How can I forget you, beautiful forested isle

- Rich ornament of this place and its basin?

- I prize all the sweet beauties of your sister

- Yet I prize even more your outstanding features.

- For, just as it is fitting for him who holds command

- To display a majesty more august and grand

- Than his subordinate; just so, to command

- You have an elevated headland which allows you oversight.

- Around you is an undulating plain,

- And the land in the vicinity <is> subject to your dominion.

- Your shores consist of rocks <suitable> for your buildings

- Or for laying the foundations of a city.

- In other places there is a little beach,

- Where a thousand times a day my spirit abides.

- But amidst <all> your beauties I admire a little stream

- Which presses gently the fresh herbage

- Of a little valley that descends in the hollow of your breast

- Plunging its course into the waves of the sea:

- Little stream that has tempted me a hundred times with its waters,

- Its charm forcing me to lie down beside it.

- Having all that, Island high and deep,

- Island worthy dwelling place of the greatest King on earth,

- Having all that, I say, what more can be lacking

- To create over there the city we need

- Except for every man to have his sweetheart by his side

- In the manner which God and the Church command?

- For your soil is good and fertile and pleasing

- And never its cultivator will be displeased with it.

- We <ourselves> are in a position to speak of it who, of many seeds

- Sown there have had first-hand experience.

- What else can I say worthy of the praise of your beauty?

- What shall I add here than that inside your domain

- One finds in great measure products of Nature:

- Raspberries, strawberries, peas, without any cultivation?

- Or shall I mention as well your verdant laurel bushes

- Your unknown medicinal herbs, your red currant bushes?

- No, but without leaving your bounds,

- I will touch upon the numerous armies

- Of the scaly creatures that come every day

- Following the tidal flow to bid you good day.

.

- As soon as the season of Spring returns

- The Smelt comes in abundance, bringing news

- That Phoebus, risen above your horizon

- Has chased far from you the wintry season.

- The Herring follows after with such multitude

- That it alone can make a people rich.

- My <own> eyes have witnessed this, and yours as well

- Who have had the care of our nourishment

- When, occupied elsewhere, your diligent hands

- Were unable to cope with the pleasing catch

- That the sluice of a mill sent into your nets.

- The Bass follows in the wake of the Herring

- And at the same time the little Sardine,

- The Crab, <and> the Lobster follow the sea shore

- With a similar result; the Dolphin, <and> the Sturgeon

- Arrive among the multitude together with the Salmon

- As do the Turbot, the Tomcod, <and> the Eel,

- The Shad, the Halibut, the Loach, and the Sand Eel:

- You, Sand Eel, although little, have impressed your name

- On that river whose renown I sing.

- But that is not all, for you have more

- Multitudes that pay you homage every day,

- The Pollock, the Finback Whale and the Squid and the Angler Fish,

- The Porpoise, The Blower Dolphin, the Sea Urchin, the Mackerel,

- You have the Grey Seal which, in a large pod

- Wallow in the light of day on your muddy bottom,

- You have the Dogfish, the Plaice , and a thousand other fish

- Which I do not know, nurselings of your waters.

.

- Shall I not mention the happily fecund Cod

- Which abound throughout that sea everywhere.

- Cod, <even> if you are not one of those delicate dishes

- With which gourmets spice their plates,

- I will say nevertheless that by you is sustained

- Almost the entire universe. O, how content will be

- That person one day who will have at his doorstep

- That which a distant world will come to seek from it!

- Beautiful Isle, You therefore have that manna aplenty

- Which I love more than Taprobane’s

- Beauties that they deem worthy of the blessed ones

- Who go about drinking the fragrant nectar of the Gods.

- And to demonstrate one more time your supreme power

- Whales honour you daily, and come of their own accord

- To salute you every day, until the ebb leads them

- Into the wide Ocean where they have their pleasure.

- Of this I will render faithful testimony,

- Having seen them many times visit this shore

- And consort at their leisure inside this harbor.

.

- But all these animals, all these creatures <from> here

- Depart when Phebus is about to approach the boundary

- Of the celestial mansion, where dwells Capricorn,

- And go in search of the shelter of Thetys’s depth

- Or often seek out a milder region for their pasture.

- In this harsh season there only remain close to you

- Clams, Cockles, and Mussels

- To sustain the one who will not, in a timely fashion,

- (Either poor, or lazy) have done any harvesting,

- Such as the people here who take no care to hunt

- Until hunger constrains and pursues them,

- And the weather is not always favorable for the hunter

- Who actually does not wish for the mildness of good weather

- But strong ice, or deep snow

- When the Sauvage wants to catch from the watery depths

- The industrious Beaver (that builds its home

- On the lakeshore, where it fashions its lair

- Vaulted in a way incredible to man,

- And a thousand times more admirable than our palaces

- Leaving it only one exit towards the lake

- To cheer itself down in the watery element)

- Or when he wants to spy in the woods the lair

- Either of the Royal Moose or the fleet-footed Deer,

- Of the Rabbit, Fox, Caribou, Bear,

- Of the Squirrel, the Otter with its silken fur,

- Of the Porcupine, <and> the so-called wild Cat

- (Which rather has the body of a leopard)

- Of the Mink with its soft fur in which Kings clothe themselves

- Or the musk Rat, all dwellers of these woods,

- Or of that animal which, loaded with fat,

- Has the cunning skill to climb on high

- Building its lodge on an elevated branch

- To discourage the one who goes in pursuit of it

- And lives, by that ruse, in the greatest security

- Not fearing (as it seems) any violence:

- Nibachés <raccoon> is its name. Not that in spring

- He does not have occasion for that hunt

- But the catch from fishing is more reliable then.

.

- Farewell, therefore, I say unto you, Isle of abundant beauty,

- And you birds, too, of water and forest

- That will be the witnesses of my sad regrets.

- For it is with great regret, and I cannot pass over it in silence,

- That I leave this place, although rather solitary.

- For it is with great regret that now I see

- Shaken the subject of introducing our Faith here

- And the Name of our Great God hidden in silence,

- Who had touched the conscience of this people.

- Eagles that inhabit the tops of high pines

- Since Jupiter has entrusted his secrets to you,

- Go up to the heavens to announce this matter

- And how much suffering I have of this inside my soul,

- Then return swiftly to the French Monarch of France

- To relate to him the decree of the mighty King of Kings.

- For to him is given this inheritance from heaven

- In order that in his name hereafter <and> forever

- The Everlasting One be worshipped in a holy manner

- And that his great name be revered by a hundred nations.

- And to motivate him more to do this thing

- <God> has wanted to attract him by a hundred kinds of profit

- Having made our labours commensurate with our desires

- And having completed them with ten thousand pleasures.

- For the earth here is not as a fool would guess,

- <As> she produces copiously for him who has experience

- Of the pleasures of gardening and the labour of the fields.

.

- And if you want the sweet song of birds as well,

- <This land> has the Nightingale, the Blackbird, the Linnet,

- And many another not known that sings pleasantly

- In Spring. If you want fowl

- That go and feed on the water’s edge

- <This land> has the Cormorant, the Mallow, the Seagull,

- The Canada Goose, the Heron, the Crane, the Lark,

- And the Goose , and the Duck. Six types of Duck,

- Whose many colours make as many lures

- That rivet my eyes. Do you want also

- Those birds of prey with which the Nobleman distinguishes himself?

- <This land> has the Eagle, the Owl, the Falcon, the Vulture,

- The Saker Falcon, the Sparrow Hawk, the Merlin, the Goshawk,

- And, in short, all the birds of noble hawking

- And beyond these yet another infinite multitude

- Which we do not have in common. But <this land> has the Curlew

- The Egret, the Cuckoo, the Woodcock, and the Redwing,

- The Dove, the Jay, the Owl, the Swallow,

- The Woodpigeon, the Green Finch, with the Turtledove,

- The Hoopoe, the lascivious Sparrow,

- The multi-coloured Ptarmigan, and also the Crow.

- What more shall I say? Will someone <at least> be able to believe

- That God himself has wanted to manifest his glory

- By creating a little bird similar to a butterfly

- (That does not exceed the size of a cricket)

- Displaying on its back a green-golden plumage

- And a red and white colour on the rest of its chest.

- Amazing little bird, why then, <as if> envious,

- Have you made yourself invisible to my eyes a hundred times,

- While passing lightly by my ear

- You only left the marvel of a soft sound?

- I would not have been cruel to your rare beauty

- <Un>like others who have treated you fatally

- If you had deemed me worthy to come and portray you.

- But although you did not want to hear my wish

- I will not give up celebrating your name nevertheless

- And make that you be of great renown among us.

- For I admire you as much in your smallness

- As I do the elephant in its vast size.

- Niridau is your name which I do not wish to change

- In order to impose one that would be foreign:

- Niridau, delicate little bird by nature,

- That takes the sweet nourishment of bees

- Syphoning the fragrant flowers of our gardens,

- And the rarest sweets from the forest edge.

.

- To these dwellers of the sky may I add, without offending,

- The excellence of a tiny winged folk?

- These are fireflies, which at nightfall

- Shine with brilliant clarity among the trees

- Darting here and there in such great throngs

- That the luminous band of starry sky

- Itself seems to hold no greater wonder.

- Therefore, commemorating here

- <All> the beauties of this place, it is indeed reasonable

- That you be included and hold a fitting place among them.

.

- But since our sails are already set

- And <we> are going to see again those who believe us perished

- I say Farewell once more to your beautiful gardens

- That have nourished us with your medicinal herbs,

- Nay also relieved our need

- <And> more than the art of Paean have kept us healthy.

- You have certainly given back to us in abundance

- The fruit of our labours in accordance with our sowing.

- So what does it matter if it ever happens

- (And which it necessarily will do in the future)

- That the soil here needs to be made more appealing

- And improved sometimes by human labour?

- Who will believe that the rye, and the hemp, and the peas

- Have surpassed twice the height of a young man?

- Who will believe that the so-called Indian corn

- Rises up so high in this season

- That it seems to be carried by insufferable pride

- To make itself, haughty, resemble a woodland?

- Ah! What great sadness it is for me not to be able to wait for

- The fruit that in little time you promise to render!

- How disturbing it is for me not to see the season

- When the squash and the melon will ripen

- And the cucumber as well: And <I> also grieve

- At not seeing at all come to fruition my wheat, my oats,

- And my barley and my millet, since the Sovereign

- Has blessed me in this modest effort with his hand.

- And yet, here it is the thirtieth day of the

- Month that once used to be the fifth in rank.

.

- Nations of all parts far away from here

- Do not marvel at this

- And do not at all consider us as being in a cold region,

- <As> this is not at all <like> Flanders, Scotland, nor Sweden,

- The sea here does not freeze over, and the cold seasons

- Have never forced me to save the half-burnt firewood.

- And if in your country summer arrives earlier than here

- You experience winter’s inclemency earlier.

- But you are staying yet, Poutrincourt, waiting

- Until your harvest is ready: And we, nevertheless,

- We set sail for Canso where the ship awaits you

- Which from there is due to convey all of us to France.

- For now, beautiful ears of grain, ripen quickly,

- May God the Almighty give you growth

- In order that one day his glory may resound

- When we shall commemorate his blessings

- Among which we will count as well

- The care which he will have taken to gather into his mercy

- These vagabond peoples one calls Sauvages,

- Dwellers of these forests and marine shores,

- And a hundred peoples more who are located on all sides

- To the south, West and North settled in one place

- Who love to work and who cultivate the soil

- And who, in freedom, live more contentedly from their produce than we

- But their condition is deplorable in this respect

- That they have not been instructed about the world to come.

.

- Why, o Almighty one, why then have you

- Rejected this race from your face until now

- And why do you leave to hell to devour,

- So many human beings who ought to triumph over it,

- Seeing that they are, like us, <of> your work and making

- And have from you received our fragile nature?

- Open therefore the treasuries of your compassion[s]

- And pour out onto them your blessings

- In order that soon they may be your blessed heritage

- And intone aloud your goodness throughout all the ages.

- As soon as your sun will shine on them

- Just as soon we will see this people worship you.

- Witness be the true conversations

- Poutrincourt held with these pitiful people

- When he taught them our Religion

- And often showed them the ardent desire

- He had to see them inside the fold

- Which Christ has redeemed by the price of his life.

- Clearly moved, they on their part gave witness

- With their mouths and hearts of the desire they had

- To be more amply instructed in the teaching

- Within which it is proper for the faithful make their way.

.

- Where are you, Prelates, that you do not pity

- This people that makes up half the world?

- <Why> don’t you at least give aid to those whose zeal

- Transports them so far as if under His wing

- To establish here God’s holy law

- With so much hardship, care and emotion?

- These peoples are not brutal, barbaric or savage,

- If you <choose> not to call by such names the men of yore,

- They are subtle, clever and of very sound judgment

- And <I> have not known a single one who lacked understanding

- Only they need a father to teach them

- To cultivate the earth, to cultivate the vine,

- To live in an organized fashion, to be economical

- And to dwell in fixed habitations from here on.

- For the rest, in our opinion, they are full of innocence

- If <only> they had knowledge of their creator.

- <But> because they do not know Him, neither mouth nor heart

- Ravishes God’s honour through blasphemy.

- They do not know the work of the amorous potion

- Nor have they knowledge of the use of aconite,

- Their mouths do not vomit forth our curses

- Their spirits are not given over to our inventions

- For oppressing the other, <and> the cruel avarice

- of an all-consuming preoccupation does not torment their souls.

- But they have the hospitality of the Gaulois,

- Who valued it so highly in their days of old.

- Their greatest vice is the love of vengeance

- When their enemy has offended them in some way.

.

- Farewell unto you, then, poor people, and <I> am incapable

- To express the sadness I feel

- In leaving you thus, without having seen as yet

- One of you made to truly worship God.

.

- Let us depart, then, from this harbor, the East wind permitting,

- For on these coasts the West wind is prevalent

- <And> moreover, this sea is often covered by fog

- Which causes the total loss of incautious men.

.

- Farewell for the last time, Rocks rearing high,

- Proudly raising up your caverns

- From whence pour forth without end abundant showers

- Which are supplied by the waters coursing down the mountains.

- Farewell, then, to you as well, Caves, that have pleased me

- When beneath your halls in bright daylight I have seen outlined

- The attractive colours of the Rainbow.

.

- Now that we are in sight of the awesome waves

- Of the Ocean deep, will I be able to pass by

- Without saluting from afar, or leaving <without> a Farewell

- To the land that received our <country> France

- When she first came to establish herself here?

- Island, I salute you, Isle of Saint Croix,

- Island that was the first dwelling place of our poor <fellow> French

- Who suffered major hardships while dwelling with you,

- But <it is> our bad habits that often cause us these injuries.

- I revere, however, your pure antiquity,

- The scented cedars on your side

- Your workshops, your lodgings, your superb warehouse,

- Your gardens choked by new weeds:

- But I honour above all on account of our dead

- The place that holds their bodies in its keeping

- Which I have not been able to behold without a power of tears

- So much did these terrible exploits sadden my heart.

- Be at peace, then, and may you one day

- Find yourselves in glory in the heavenly mansion.

- But nevertheless, DE MONTS, you take with you the glory

- Of having obtained victory over a thousand deaths,

- A true witness to your great courage,

- Be it when you battled the fury of the waves

- While coming to visit this faraway province

- In order to follow the will of HENRY, our Prince,

- Or when in front of your eyes you watched <them> die

- Those <buried> there who followed you to that fateful location.

.

- Far behind I leave you, mines to be

- Which the massive rocks lodge deep in their veins,

- Mines of bronze, iron and steel, and of silver,

- And of pit coal, in order to salute the people

- Who cultivate their land by hand, the Armouchiquois.

- I salute you, then, quarrelsome nation

- (For you have failed us on account of treason)

- To say unto you that one day we will obtain satisfaction

- And with greater effect, of your presumptuousness,

- Just as your offspring will be accursed among us.

- But your earth I want to salute in all its goodness

- For she is sure to give us an ample return

- When she will experience French cultivation.

- For in her provident Nature has already

- Implanted the vine so copiously

- And with such beauty, that Bacchus himself,

- If invoked, would not know how to improve on it.

- But its people, unaware, do not know the use of its fruit.

- Earth, you also have, with beans and grain,

- Your subterranean silos filled in harvest time.

- But although you give your produce abundantly

- Producing other fruits without human assistance

- Such as the hemp, squash and nuts we have seen,

- Your beans, nor your grain, in any case, you do not

- Produce without work, but your populace, in great number,

- <Already> breaks you with a sharp cutting timber, and turns you over

- To plant its seed there, in the Spring.

.

- But one more thing I must mention

- Which obliges me to write about it because of its rarity,

- <And> that is the product produced by the stalk of the hemp plant

- <A> product worthy of being held precious by Kings

- <And> most delicious for the repose of the body:

- It is a white, thin and fine silk

- Which Nature produces in the hollow of a shell,

- Silk which one will be able to employ for many a use

- And which workers will turn into cotton

- When you <Earth>, inhabited by good artisans,

- Will be controlled by a willed sedentarism.

.

- May I see that thing arrive soon,

- And careful Frenchmen cultivate your fields,

- Away from the cares of a life of hardship

- Far from the noise of the common crowd, and from deceit.

.

- Seeking on Neptune’s bosom rest without rest,

- I have fashioned these verses on the swell of his waves.

- LESCARBOT

—Translated by Haijo Westra

Based on the Histoire de la Nouvelle-France, 1617 edition, produced by Rénald Lévesque and published by the Gutenberg Project (2007) at www. gutenberg

§

Detail from Champlain map

Detail from Champlain map

A-DIEU A LA NOUVELLE-FRANCE

Du 30 Juillet 1607.

FAUT-il abandonner les beautez de ce lieu,

Et dire au Port Royal un eternel Adieu?

Serons-nous donc toujours accusez d’inconstance

En l’établissement d’une Nouvelle-France?

Que nous sert-il d’avoir porté tant de travaux,

Et des flots irritez combattu les assaux,

Si notre espoir est vain, & si cette province

Ne flechit souz les loix de HENRY notre Prince?

Que vous servit-il d’avoir jusques ici

Fait des frais inutils, si vous n’avez souci

de recuillir le fruit d’une longue depense,

Et l’honneur immortel de votre patience?

Ha que j’ay de regrets que ne sçavez pas

De cette terre ici les attrayans appas.

Et bien que le Flamen vous ait fait une injure,

L’injure bien souvent se rend avec usure.

Il faut doncques partir, il faut appareiller,

Et au port Sainct-Malo aller l’ancre mouiller.

PERE DE L’UNIVERS, qui commandes aux ondes,

Et qui peux assecher les mers les plus profondes,

Donne nous de franchir les abymes des eaux

Dont tu as separé tous ces peuples nouveaux

Des peuples baptizés, & sans aucun naufrage

Du royaume François voir bien-tot le rivage.

Adieu donc beaux coteaux & montagnes aussi,

Qui d’un double rempar ceignez ce Port ici.

Adieu vallons herbus que le flot de Neptune

Va baignant largement deux fois à chaque lune,

Et au gibier aussi, qui pour trouver pâture

Y vient de tous cotez tant qu’il y a verdure.

Adieu mon doux plaisir fonteines & ruisseaux,

Qui les vaux & les monts arrousez de vos eaux.

Pourray-je t’oublier belle ile forètiere

Riche honneur de ce lieu & de cette riviere?

Je prise de ta soeur les aimables beautés,

Mais je prise encor plus tes singularités.

Car comme il est séant que celui qui commande

Porte une Majesté plus auguste & plus grande

Que son inferieur; ainsi pour commander

Tu as le front haussé qui te fait regarder.

A l’environ de toy une ondoyante plaine,

Et la terre alentour sujette à ton domaine

Tes rives sont des rocs, soit pour tes batimens,

Soit pour d’une cité jetter les fondemens.

Ce sont en autres parts une menuë arene,

Où mille fois le jour mon esprit se pourmene.

Mais parmi tes beautés j’admire un ruisselet

Qui foule doucement l’herbage nouvelet

D’un vallon que se baisse au creux de ta poitrine,

Precipitant son cours dedans l’onde marine.

Ruisselet qui cent fois de ses eaux m’a tenté,

Sa grace me forçant lui prèter le côté.

Ayant dont tout cela, Ile haute & profonde,

Ile digne sejour du plus grand Roy du monde,

Ayant di-je, cela, qu’est-ce que te defaut.

A former pardeça la cité qu’il nous faut,

Sinon d’avoir prés soy un chacun sa mignone

En la sorte que Dieu & l’Eglise l’ordonne?

Car ton terroir est bon & fertile & plaisant,

Et oncques son culteur n’en sera deplaisant.

Nous en pouvons parler, qui de mainte semence

Y jettée, en avons certaine experience.

Que puis-je dire encor digne de ton beau los?

Qu’adjouteray-je ici que dedans ton enclos

Se trouvent largement produits par la Nature

Framboises, fraises, pois, sans aucune culture?

Ou bien diray-je encor tes verdoyans lauriers,

Tes Simples inconus, tes rouges grozeliers?

Non, mais tant seulement sans sortir tes limites,

Ici je toucheray les nombreux exercices

Des peuples écaillez qui viennent chaque jour,

Suivans le train du flot te donner le bon-jour.

Si-tot que du Printemps la saison renouvelle

L’Eplan vient à foison, qui t’apporte nouvelle

Que Phoebus elevé dessus ton horizon

A chassé loin de toy l’hivernale saison.

Le Haren vient apres avecque telle presse

Que seul il peut remplir un peuple de richesse.

Mes yeux en sont témoins, & les vostres aussi

Qui de nôtre pature avés eu le souci,

Quand, ailleurs occupez, vôtre main diligente

Ne pouvoit satisfaire à la chasse plaisante

Qu’envoyoit en voz rets l’ecluse d’un moulin.

Le Bar suit par-apres du Haren le chemin.

Et en un méme temps la petite Sardine,

La Crappe, & le Houmar, suit la côte marine

Pour un semblable effect; le Dauphin, l’Eturgeon

Y vient parmi la foule avecque le Saumon,

Comme font le Turbot, le Pounamou, l’Anguille,

L’Alose, le Fletan, & la Loche, & l’Equille:

Equille qui, petite, as imposé le nom

A ce fleuve de qui je chante le renom.

Mais ce n’est ici tout, car tu as davantage

De peuples qui te font par chacun jour homage,

Le Colin, le Joubar, l’Encornet, le Crapau,

Le Marsoin, le Souffleur, l’Oursin le Macreau,

Tu as le Loup-marin, qui en troupe nombreuse

Se vautre au clair du jour sur ta vase bourbeuse,

Tu as le Chien, la Plie, & mille autres poissons

Que je ne conoy point, de tes eaux nourrisons.

Tairay-je la Moruë heureusement feconde,

Qui par tout cette mer en toutes parts abonde?

Moruë si tu n’es de ces mets delicats

Dont les hommes frians assaisonnent leurs plats,

Je diray toutefois que de toy se sustente

Prèque tout l’Univers. O que sera contente

Celle personne un jour, qui à sa porte aura

Ce qu’un monde eloigné d’elle recherchera!

Belle ile tu as donc à foison cette manne,

Laquelle j’ayme mieux que de la Taprobane

Les beautez que lon feint dignes des bien-heureux

Qui vont buvans des Dieux le Nectar savoureux.

Et pour montrer encor ta puissance supreme,

La Baleine t’honore & te vient elle-méme

Saluer chacun jour, puis l’ebe la conduit

Dans le vague Ocean où elle a son deduit.

De ceci je rendray fidele temoignage,

L’ayant veu mainte fois voisiner ce rivage,

Et à l’aise nouer parmi ce port ici.

Mais tous ces animaux, mais tous ces peuples ci

S’écartent quand Phoebus veut approcher la borne

Du celeste manoir, où git le Capricorne,

Et vont chercher l’abri du profond de Thetys,

Ou d’un terroir plus doux vont souvans le pâtis.

Seulement pres de toy en cette saison dure

La Palourde, la Coque, & la Moule demeure

Pour sustenter celui qui n’aura de saison

(Ou pauvre, ou paresseux) fait aucune moisson,

Tel que ce peuple ici qui n’a cure de chasse

Jusqu’à ce que la faim le contraigne& pourchasse,

Et le temps n’est toujours favorable au chasseur.

Qui ne souhaite point d’un beau temps la douceur,

Mais une forte glace, ou des neges profondes,

Quand le Sauvage veut tirer du fond des ondes

L’industrieux Castor (qui sa maison batit

Sur la rive d’un lac, où il dresse son lict

Vouté d’une façon aux hommes incroyable,

Et plus que noz palais mille fois admirable,

Y laissant vers le lac un conduit seulement

Pour s’aller égayer souz l’humide element)

Ou quand il veut quéter parmi les bois le gite

Soit du Royal Ellan, soit du Cerf au pié vite,

Du Lapin, du Renart, du Caribou, de l’Ours,

De l’Ecureu, du loutre à peau-de-velours

Du Porc-epic du Chat qu’on appelle sauvage,

(Mais qui du Leopart ha plustot le corpsage)

De la Martre au doux poil dont se vétent les Rois,

Ou du Rat porte-muse, tous hôtes de ces bois,

Ou de cet animal qui tout chargé de graisse

De hautement grimper ha la subtile addresse,

Sur un arbre elevé sa loge batissant

Pour decevoir celui qui le va pourchassant,

Et vit par cette ruse en meilleure asseurance

Ne craignant (ce lui semble) aucune violence,

Nibachés est son nom. Non que sur le printemps

Il n’ait à cette chasse aussi son passe-temps.

Mais alors du poisson la peche est plus certaine.

Adieu donc je te dis, ile de beauté pleine,

Et vous oiseaux aussi des eaux & des forêts

Qui serez les témoins de mes tristes regrets.

Car c’est à grand regret, & je ne le puis taire,

Que je quitte ce lieu, quoy qu’assez solitaire.

Car c’est à grand regret qu’ores ici je voy

Ebranlé le sujet d’y entrer nôtre Foy,

Et du grand Dieu le nom caché souz le silence,

Qui à ce peuple avoit touché la conscience.

Aigles qui des hauts pins habitez les sommets,

Puis qu’à vous Jupiter a commis ses secrets,

Allez dedans les cieux annoncer cette chose,

Et combien de douleur j’en ay en l’ame enclose,

Puis revenez soudain au Monarque François

Lui dire le decret du puissant Roy des Roys.

Car à lui est du ciel donné cet heritage,

Afin que souz son nom ci-aprés en tout âge

L’Eternel soit ici sainctement adoré,

Et de cent nations son grand nom reveré:

Et pour mieux l’emouvoir à cette chose faire,

Par cent sortes de biens il l’a voulu attraire,

Ayant à noz labeurs fait selon noz désirs,

Et iceux terminé de dix mille plaisirs.

Car la terre ici n’est telle qu’un fol l’estime,

Elle y est plantureuse à cil qui sçait l’escrime

Du plaisant jardinage & du labeur des champs.

Et si tu veux encor des oiseaux les doux chants,

Elle a le Rossignol, le Merle, la Linote,

Et maint autre inconu, qui plaisamment gringote

En la jeune saison. Si tu veux des oiseaux

Qui se vont repaissans sur les rives des eaux,

Elle a le Cormorant, la Mauve, Ma Mouette,

L’Outarde, le Heron, la Gruë, l’Alouette,

Et l’Oye, et le Canart. Canart de six façons,

Dont autant de couleurs sont autant d’hameçons

Qui ravissent mes yeux. Desires-tu encore

De ces oiseaux chasseurs dont le Noble s’honore?

Elle a l’Aigle, le Duc, le Faucon, le Vautour,

Le Sacre, l’Epervier, l’Emerillon, l’Autour,

Et bref tous les oiseaux de haute volerie

Et outre iceux encore une bende infinie

Qui ne nous sont communs. Mais elle a le Courlis

L’Aigrette, le Coucou, la Becasse & Mauvis,

La Palombe, le Geay, le Hibou, l’Hirondelle,

Le Ramier, la Verdier, avec la Tourterelle,

Le Beche-bois huppé, le lascif Passereau,

La perdris bigarrée, & aussi le Corbeau.

Que diray-je plus? Quelqu’un pourra-il croire

Que Dieu méme ait voulu manifester sa gloire

Creant un oiselet semblable au papillon

(Du moins n’excede point la grosseur d’un grillon)

Portant dessus son dos un vert-doré plumage,

Et un teint rouge-blanc au surplus du corps-sage?

Admirable oiselet, pourquoy donc, envieux,

T’es-tu cent fois rendu invisible à mes ieux,

Lors que legerement me passant à l’aureille

Tu laissois seulement d’un doux bruit la merveille?

Je n’eusse esté cruel à ta rare beauté,

Comme d’autres qui t’ont mortellement traité,

Si tu eusses à moy daigné te venir rendre.

Mais quoy tu n’as voulu à mon desir entendre.

Je ne lairray pourtant de celebrer ton nom,

Et faire qu’entre nous tu sois de grand renom.

Car je t’admire autant en cette petitesse

Que je fay l’Elephant en sa vaste hautesse.

Niridau c’est ton nom que je ne veux changer

Pour t’en imposer un qui seroit étranger.

Niridau oiselet delicat de nature,

Qui de l’abeille prent la tendre nourriture

Pillant de noz jardins les odorantes fleurs,

Et des rives des bois les plus rares douceurs.

A ces hotes de l’air pourray-je sans offense

D’un petit peuple ailé adjouter l’excellence?

Ce sont mouches, de qui sur le point de la nuit

La brillante clarté parmi les bois reluit

Voletans ça & là d’une presse si grande,

Que du ciel etoilé la lumineuse bende

Semble n’avoir en soy plus d’admiration.

Faisant doncques ici commemoration

Des beautez de ce lieu, il est bien raisonnable

Que vous y teniez rang & place convenable.

Mais puis que ja desja noz voiles sont tendus,

Et allons revoir ceux qui nous cuident perdus,

Je dis encore Adieu à vous beaux jardinages,

Qui nous avez cet an repeu de vos herbages,

Voire aussi soulagé nôtre necessité

Plus que l’art de Pæon n’a fait nôtre santé.

Vous nous avez rendu certes en abondance

Le fruit de noz labeurs selon notre semence.

Hé que sera-ce donc s’il arrive jamais

(Ce qu’il est de besoin qu’on face desormais)

Que la terre ici soit un petit mignardée,

Et par humain travail quelquefois amendée?

Qui croira que le segle,& la chanve, & le pois,

Le chef d’un jeune gars ait surpassé deux fois?

Qui croira que le blé que l’on appelle d’Inde

En cette saison-ci si hautement se guinde

Qu’il semble estre porté d’insupportable orgueil

Pour se rendre, hautain, aux arbrisseaux pareil?

Ha que ce m’est grand deuil de ne pouvoir attendre

Le fruit qu’en peu de temps vous promettiez nous rendre!

Que ce m’est grand émoy de ne voir la saison

Quand ici meuriront la Courge, le Melon,

Et le Cocombre aussi: & suis en méme peine

De ne voir point meuri mon Froment, mon Aveine

Et mon Orge & mon Mil, pois que le Souverain

En ce petit travail m’a beni de sa main.

Et toutefois voici de ce mois le trentieme,

Mois qui jadis estoit en ordre le cinquième

Peuples de toutes parts qui estes loin d’ici

Ne vous emerveillez de cette chose ci,

Et ne nous tenez point comme en region froide,

Ce n’est point ici Flandre, Ecosse, ni Suede,

La mer ici ne gele, & les froides saisons

Ne m’ont oncques forcé d’y garder les tisons.

Et si chez vous l’eté plustot qu’ici commence,

Plustot vous ressentez de l’hiver l’inclemence.

Mais tu restes encor, Poutrincourt attendant

Que ta moisson soit préte: & nous nous cependant

Faisons voile à Campseau où t’attent le navire

Que de là doit tous en la France conduire.

Cependant beaux epics meurissez vitement,

Dieu le Dieu tout-puissant vous doint accroissement,

Afin qu’un jour ici retentisse sa gloire

Lors que de ses bien-faits nous ferons la memoire.

Entre lesquelz bien-faits nous conterons aussi

Le soin qu’il aura eu de prendre à sa merci

Ces peuples vagabons qu’on appelle Sauvages

Hotes de ces forèts & des marins rivages,

Et cent peuples encor qui sont de tous côtez

Au Su, à l’Oest au Nort de pié-ferme arretez

Qui aiment le travail, qui la terre cultivent,

Et libres, de ses fruits plus contens que nous vivent,

Mais en ce deplorable est leur condition,

Que du siecle futur ilz n’ont l’instruction.

Pourquoy, ô Tout-puissant, pourquoy donc cette race

As-tu jusques ici rejetté de ta face,

Et pourquoy laisses tu devorer à l’enfer,

Tant d’humains qui devroient dessus lui triompher

Veu qu’ilz sont comme nous ton oeuvre & ta facture,

Et ont de toy receu nôtre fraile nature?

Ouvre donc les thresors de tes compassions,

Et verse dessus eux tes benedictions,

Afin qu’ilz soient bien-tot ton sacré heritage,

Et chantent hautement tes bontés en tout âge.

Si-tot que ton Soleil sur eux éclairera,

Aussi-tot cet gent d’adorer on verra.

Temoins soient de ceci les propos veritables

Que Poutrincourt tenoit avec ces miserables

Quand il leur enseignoit notre Religion,

Et souvent leur montroit l’ardente affection

Qu’il avoit de les voir dedans la bergerie

Que Christ a racheté par le pris de sa vie.

Eux d’autre part emeus clairement temoignoient

Et de bouche & de coeur le desir qu’ilz avoient

D’estre plus amplement instruits en la doctrine

En laquelle il convient qu’un fidele chemine.

Où estes vous Prelats, que vous n’avez pitié

De ce peuple qui fait du monde la moitié?

Du moins que n’aidez-vous à ceux de qui le zele

Les transporte si loin comme dessus son aile

Pour établir ici de Dieu la saincte loy

Avecque tant de peine, & de soin & d’émoy

Ce peuple n’est brutal, barbare ni sauvage,

Si vous n’appellez tels les hommes du vieil âge,

Il est subtile, habile, & plein de jugement,

Et n’en ay conu un manquer d’entendement,

Seulement il demande un pere qui l’enseigne

A cultiver la terre, à façonner la vigne,

A vivre par police, à estre menager,

Et souz des fermes toicts ci-apres heberger.

Au reste à nôtre égare il est plein d’innocence

Si de son createur il avoit la science.

Que s’il ne le conoit, sa bouche ni son coeur

Ne ravit point à Dieu par blaspheme l’honneur.

Il ne sçait le metier de l’amoureux bruvage,

De l’aconite aussi il ne sçait point l’usage,

Sa bouche ne vomit nos imprecations,

Son esprit ne s’adonne à nos inventions

Pour opprimer autrui, l’avarice cruelle

D’un souci devorant son ame ne bourrelle

Mais il a du Gaullois cette hospitalité

Qui tant l’a fait priser en son antiquité.

Son vice le plus grand est qu’il aime vengeance

Lors que son ennemi lui a fait quelque offense.

Je vous di donc Adieu, pauvre peuple, & ne puis

Exprimer la douleur en laquelle je suis

De vous laisser ainsi sans voir qu’on ait encore

Fait que quelqu’un de vous son Dieu vrayment adore

Sortons donc de ce Port à la faveur de l’Est,

Car en ces côtes ci est ordinaire l’Ouest,

Puis, souvent cette mer est de brumes couverte

Qui des hommes peu cauts cause l’extreme perte.

Adieu pour un dernier Rochers haut elevés,

Qui orgueilleusement voz grottes soulevés,

D’où distillent sans fin des pluies abondantes

Que leur versent les eaux des montagnes coulantes.

Adieu doncques aussi Grottes qui m’avez pleu

Quand souz votre lambris au clair du jour j’ay veu

Figurées d’Iris les couleurs agreables.

Ores que nous voyons les flots épouvantables

Du profond Ocean, pourray-je bien passer

Sans saluer de loin, ou quelque Adieu laisser

A la terre que a receuë notre France

Quand elle vint ici faire sa demeurance?

Ile, je te saluë, ile de Saincte Croix,

Ile premier sejour de noz pauvres François,

Qui souffrirent chez toy des choses vrayment dures,

Mais noz vices souvent nous causent ces injures.

Je revere pourtant ta freche antiquité

Les Cedres odorans qui sont à ton côté,

Tes Loges, tes Maisons, ton Magazin superbe,

Tes jardins étouffez parmi la nouvelle herbe:

Mais j’honore sur tout à-cause de noz morts

Le lieu qui sainctement tient en depost leurs corps,

Lequel je n’ay pu voir sans un effort de larmes,

Tant mon navré le coeur ces violentes armes.

Soyez doncques en paix, & puissiez vous un jour,

Vous trouver glorieux au celeste sejour.

Mais cependant, DE MONTS, tu emportes la gloire

D’avoir sur mille morts obtenu la victoire,

Témoignage certain de ta grande vertu,

Soit quand tu as des flots la fureur combattu

En venant visiter cette étrange province

Pour suivre le vouloir de HENRY nôtre Prince

Soit lors que tu voiois mourir devant tes yeux

Ceux-là qui t’ont suivi en ces funestes lieux.

Je vous laisse bien loin, pepinieres de Mines

Que les rochers massifs logent dedans leurs veines,

Mines d’airain, de fer, & d’acier, & d’argent,

Et de charbon pierreux, pour saluer la gent

Qui cultive à la main la terre Armouchiquoise.

Je te saluë donc nation porte-noise

(Car tu as envers nous forfait par trahison)

Pour te dire qu’un jour nous aurons la raison

Avecque plus d’effect de ton outrecuidance,

Si qu’entre nous sera maudite ta semence.

Mais ta terre je veux saluer en tout bien,

Car un ample rapport elle nous fera bien

Quand elle sentira du François la culture.

Car en elle desja la provide Nature

A le raisin semé si plantureusement,

Et en telle beauté, que Bacchus mémement

Ne sçauroit invoqué lui faire davantage.

Mais son peuple ignorant ne sçait du fruit l’usage.

Terre, tu as encor de féves & de blés

Tes greniers souz-terrains en la moisson comblés.

Mais quoy que tes biens tu donnes abondance

Produisant d’autres fruits sans l’humaine assistance

Tes qu’avons veu la Chanve & la Courge & la Noix,

Tes féves tu ne veux ni tes blez toutefois

Produire sans travail, mais ta grand’ populace

D’un bois coupant ta brise, & en mottes t’amasse

Pour (sur le renouveau) sa semence y planter,

Mais une chose encor il me faut reciter

Qui pour sa rareté à l’écrire m’oblige,

C’est le fruit que produit la Chanve la tige,

Fruit digne que les Rois le tiennent precieux

Pour le repos du corps le plus delicieux:

C’est une soye blanche & menuë & subtile

Que la Nature pousse au creux d’une coquille,

Soye qu’en maint usage employer on pourra,

Et laquelle en cotton l’ouvrier façonnera,

Quand de bons artisans tu seras habitée

Par une volonté de pié-ferme arretée.

Puisse-je voir bien-tot cette chose arriver,

Et le François soigneux à tes champs cultiver,

Arriere des soucis d’une peineuse vie,

Loin des bruits du commun, & de la piperie.

Cherchant dessus Neptune un repos sans repos

J’ay façonné ces vers au branle de ses flots.

—M. LESCARBOT.

(This eBook excerpt is from Project Gutenberg’s Les Muses de la Nouvelle France by Marc L’escarbot produced by Rénald Lévesque. This eBook is for the use of anyone anywhere at no cost and with almost no restrictions whatsoever. You may copy it, give it away or re-use it under the terms of the Project Gutenberg License included with this eBook or online at www.gutenberg.org.)

Champlain map detail

Champlain map detail

.

Haijo Westra has taught Classics at the University of Calgary and wrote about topics in Greek and Latin literature. More recently, he has turned to the early accounts of the East Coast written in Latin by the Jesuit Pierre Biard and the role of classical ethnography in the description of Native peoples, in particular the Micmac. The present article is his first venture into a French text of the period.

.

.

Detail from Champlain map, Nova Scotia, Bay of Fundy, etc.

Detail from Champlain map, Nova Scotia, Bay of Fundy, etc. Detail from Champlain map

Detail from Champlain map Detail from Champlain map

Detail from Champlain map Champlain map detail

Champlain map detail

Dennis & Marie

Dennis & Marie

Portrait of Evie aged four

Portrait of Evie aged four

Spring: watercolor/oil pastel/graphite on paper 11”x15”.

Spring: watercolor/oil pastel/graphite on paper 11”x15”.

Douglas Crosbie, Lynn’s father, reading to her and her baby brother James.

Douglas Crosbie, Lynn’s father, reading to her and her baby brother James.