“slipped almost totally under the radar…” (David Rivard)

“slipped almost totally under the radar…” (David Rivard)

.

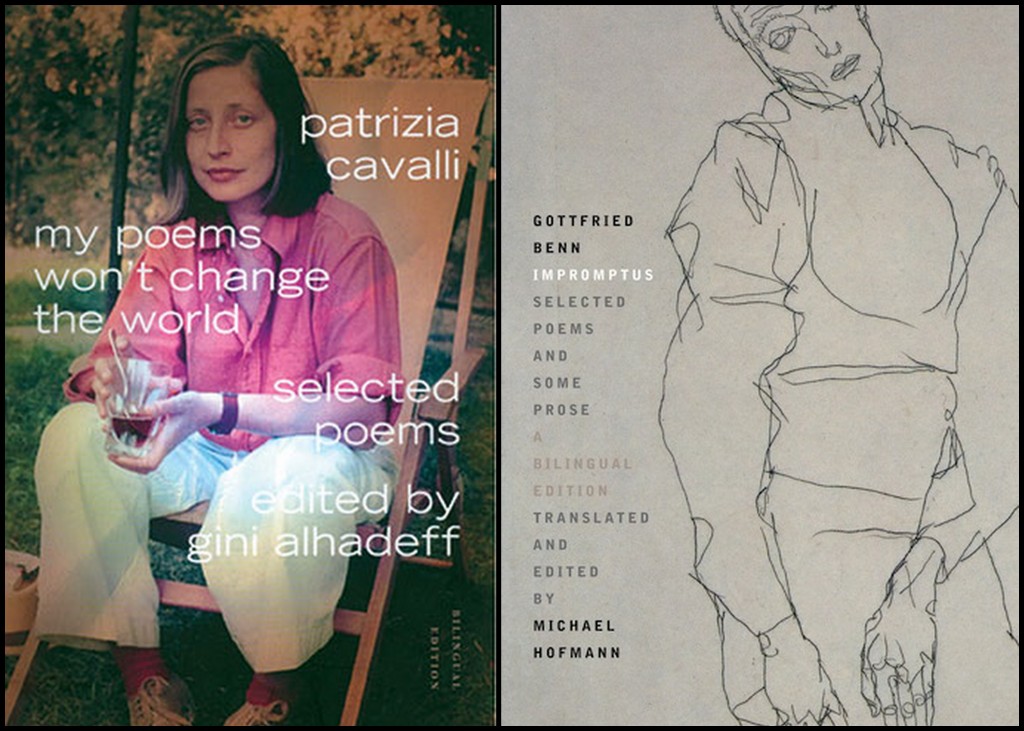

The recent passing of Mark Strand brought many things to mind—not least his important role, along with Charles Simic, in expanding the impact of European and South American poets on American poetry through their groundbreaking 1976 anthology Another Republic.

American poetry, it’s true, had already been seriously altered by an influx of work from “abroad” in the 60’s. The so-called “Generation of ‘27”—in particular, Bly, Levine, Merwin, Kinnell, and Wright—all of whom had come of age under the strictures of New Criticism, suddenly found a new set of formal means and opened-up subject matter when they started reading the poetry of the French and Spanish surrealists, classical Chinese writers like Tu Fu and Li Po, the German Expressionist Georg Trakl, and a young Swedish psychologist named Tomas Transtromer. Their work as translators, and the subsequent startling changes in their own poetry, created—for better and worse—all sorts of new vectors and undercurrents, some of which coalesced around the allied schools that came to be known as “Neo-surrealism” and “Deep Image.” Bly, in particular, was a tireless enthusiast for this new poetry, a theorizer and propagandist in his essays, and a publisher through his press and magazine, The 60’s. Through wonderful books like Leaping Poetry, a book whose insights about neurology and anthropology are debatable, if not unhinged, at moments, he helped lead an inspired loosening up of language and perception in American poetry.

Others made less dramatic, more indirect contributions: the fingerprints of the Surrealists and other European modernists were all over the New York School, if one knew where to look, absorbed into an American idiom by John Ashbery, Kenneth Koch and Frank O’Hara long before the work became more generally available in this country. How many young American poets must have gone to the cubist poetry of Pierre Reverdy simply because O’Hara had ended “A Step Away from Them” by writing “My heart is in my pocket,/it is Poems by Pierre Reverdy.”

In Another Republic, Strand and Simic brought together a much wider range of poets in translation than had been previously available, with generous selections by seventeen poets. More ethnically and aesthetically diverse (though, inexplicably, all men), the poets in Another Republic were largely the inheritors and adapters of High Modernism—sometimes combining modernist techniques with the more fabular and allegorical impulses found in folklore traditions; sometimes focusing literary cubism on the apparently banal and everyday, endowing ordinary people and places with strangeness and mystery; almost always deploying a self in the poem that was both mordantly comic and humanly vulnerable.

Paul Celan, Yehuda Amichai, Julio Cortazar, Carlos Drummond De Andrade, Zbigniew Herbert, Fernando Pessoa, Czeslaw Milosz, Yannis Ritsos, Jean Follain, and the others were largely unknown to American readers at the time. Many, if not all, had experienced exile and/or the violence of mid-century history. They often wrote with far more nuanced consciousness of the political than Americans were used to in their poetry. They were also highly tuned to the absurdities that historical fate has increasingly had in store for all of us. The variety of their approaches to writing a poem was stunning. For those in two generations of American poets who have read Another Republic, the influence has been profound I suspect.

That the book is no longer as well known as it should be, and that the poets included in it have mostly passed into the oblivion of the canonical, speaks volumes about contemporary American poetry. Solipsistic, driven by social media and the marketing campaigns of publishing companies and academic trade groups like AWP, ensconced in print and digital affiliations that function like gated-communities, monetized by the promotional efforts of well-meaning institutions such as the Academy of American Poets and bien-pensant congregations like The Dodge Festival, American poetry no longer seems as open to the influence of work in translation, despite the fact that more of it is being published than ever.

Is it possible that at this point there’s so much translated poetry available that it’s actually taken for granted? Perhaps no one is exercising the sort of editorial selectivity that Mark Strand and Charles Simic did in 1976, so the impact of great and idiosyncratic writers can no longer be felt. Ilya Kaminsky and Susan Harris’s recently published Ecco Anthology of International Poetry is huge (592 pages), an admirably comprehensive survey of 20th century world poetry—but perhaps it does a disservice by implying that all the poets in its pages are of the same value? I feel a little churlish in the face of their good work just in asking the question; but a kind of leveling out occurs with a huge book like this. Perhaps a little more curatorial pressure would have helped direct readers to the best of translated poets? Maybe not. It isn’t the fault of Kaminsky and Harris that a faith in “American Exceptionalism” rules writers here just as strongly as it does our political leaders. Translated poetry seems like just another marketing niche, easy enough to avoid if one is intent on maintaining ignorance and preserving one’s assumptions.

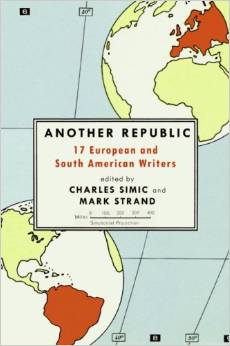

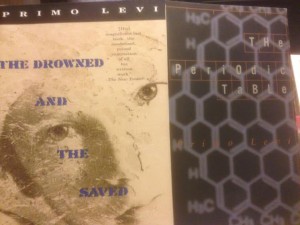

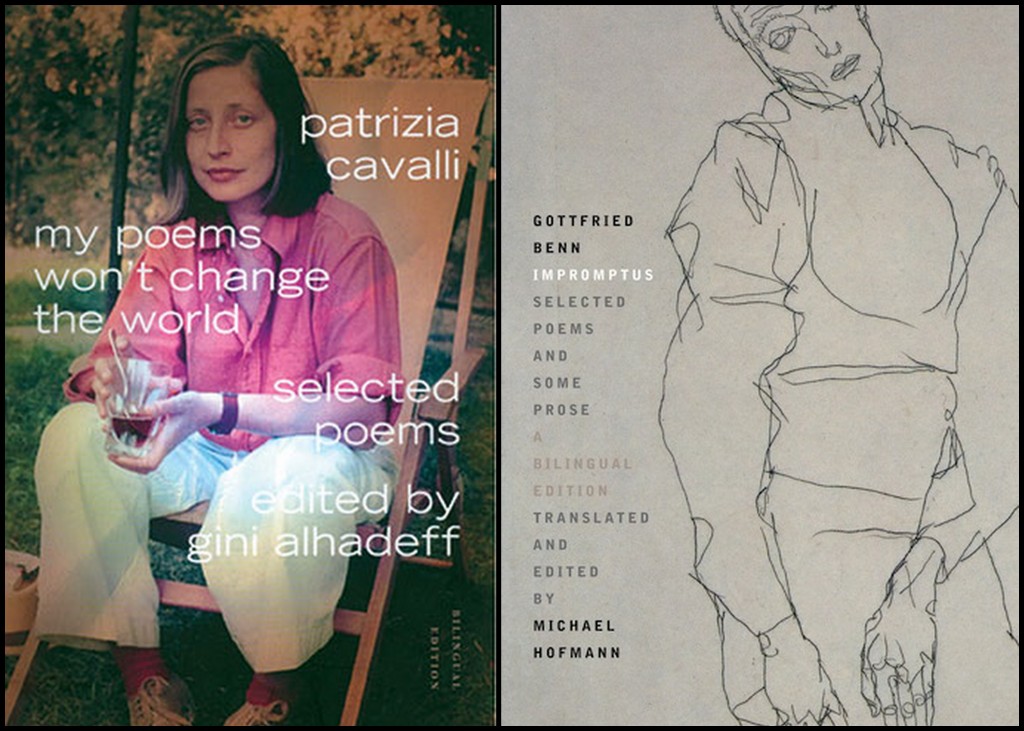

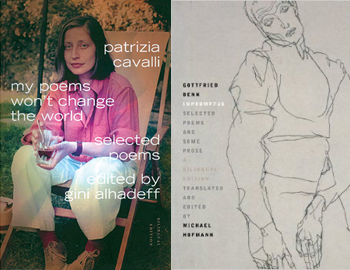

Inattention or indifference or distraction, whatever the case, some recently published books by major figures, books bringing world-class writers into English in a comprehensive way for the first time, have been largely ignored. Two in particular, both issued in 2013—by the long-dead German Expressionist, Gottfried Benn, and the very-much alive Italian poet Patrizia Cavalli—slipped almost totally under the radar. Oddly enough, both were published in handsome editions by Farrar Strauss Giroux—a house whose reputation and promotional reach would, in another time, have guaranteed a thoughtful, widespread reception. Neither seems to have found the notice and readership it deserves.

Both Benn and Cavalli offer approaches that might shake up some of the smug assumptions of the current period style. One senses in reading them that, for Benn and Cavalli, the act of making poems, of sounding their idiosyncratic music, is exhilarating—no matter the mood of the work, or the troubled waters sailed by its makers at any particular moment. Best of all, the distinctiveness of each poet’s music has largely carried over, so that a reader can feel as if he or she is encountering a poet of complex formal mastery in English.

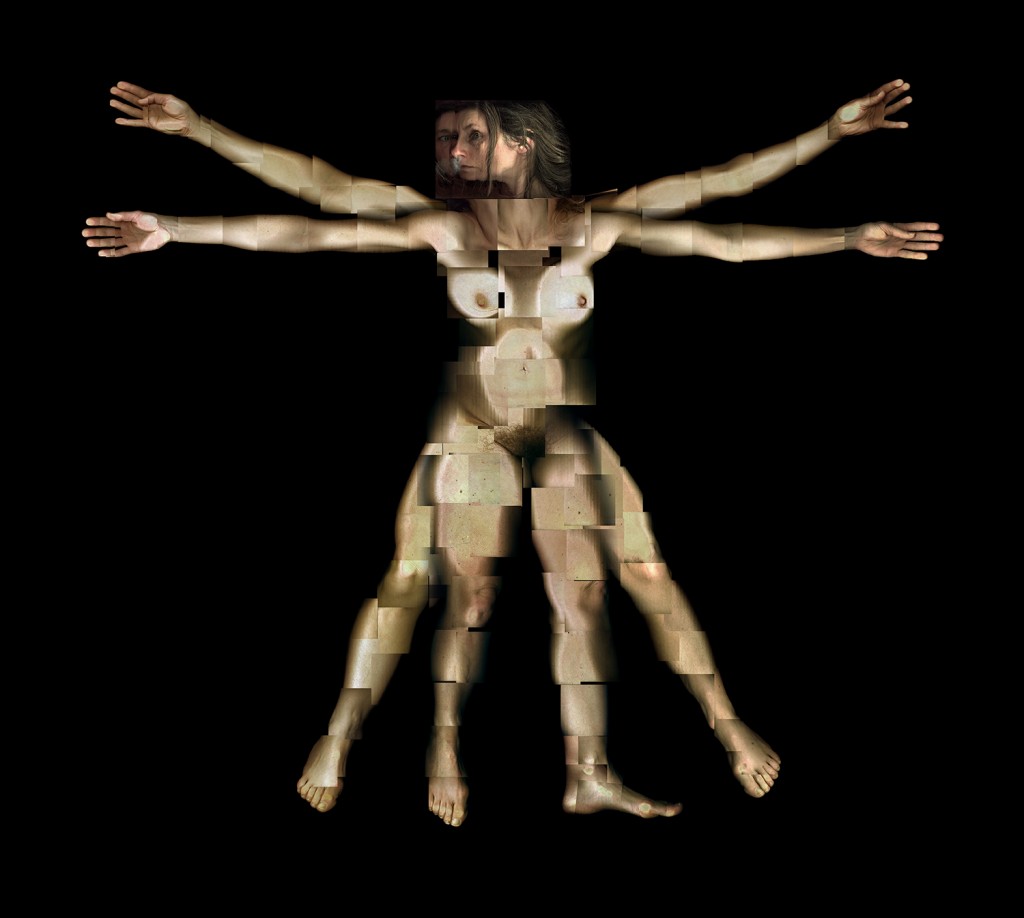

In very different ways, both Cavalli and Benn are poets whose intelligence is often registered in the body, immersed as they are in the physicality and oddness of sensation. Their complex formal processing is often abstract, non-linear, deployed in elliptical narrative and scene building; but it is carried out with an improvised, full-contact immediacy of the sort implied by the painter Philip Guston when he spoke of certain artists who have a desire to achieve “this release where their thinking doesn’t precede their doing.” As Guston might have put it, neither Benn nor Cavalli is interested in using language merely to “illustrate” their thinking—each seems to enter the poem without preconceptions about what it’s going to become.

*

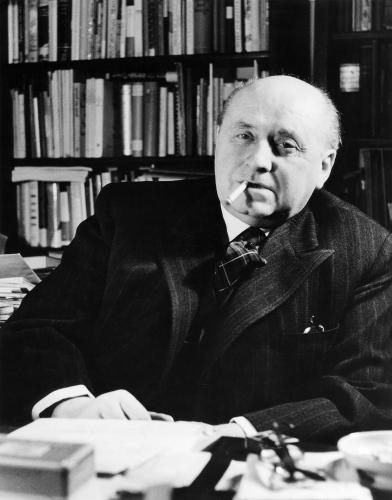

It might be over-stating the case to say that Gottfried Benn’s reputation in this country has largely had the status of a rumor. As Michael Hoffman, the translator and editor of Impromptus: Selected Poems and Some Prose, puts it in his astute introduction, it would probably be hard to fill a room here with people capable of having a serious conversation about Benn, despite the wide acknowledgment in Germany of his being “the greatest German poet since Rilke.” One slender book of translations has previously appeared of Benn’s work, in print from New Directions since the late 1950’s despite suffering from its translator’s stodgy approach. In the United States at least, Benn’s posthumous existence has been subjected to a neglect even more encompassing than what he experienced while alive. One couldn’t even say that he’s a poet’s poet exactly.

If Benn is known here at all, it is for one poem in particular, that archetypal, foundational piece of early 20th century Expressionism, “Little Aster.”

Little Aster

A drowned drayman was hoisted on to the slab.

Someone had jammed a lavender aster

between his teeth.

As I made the incision up from the chest

with a long knife

under the skin

to cut out tongue and gums,

I must have nudged it because it slipped

into the brain lying adjacent.

I packed it into the thoracic cavity

with the excelsior

when he was sewn up.

Drink your fill in your vase!

Rest easy,

little aster!

Appearing in Benn’s first collection, a 1912 chapbook called Morgue and Other Poems, the poem can hardly surprise in the way it did a hundred years ago—for one thing, the radical approach and fresh subject matter of Expressionism has been so unconsciously diffused into the postmodernist landscape that a piece like this can almost seem a cultural cliché: the granddaddy of undergraduate punk/goth shock tableaux. And like certain other products of the early Modernist effort to sweep away the crapola of late Victorian furniture and sentiment—say Pound’s “In A Paris Metro”—the poem feels as if it’s a bit of a one-trick pony.

The poem’s true power, one that would only amplify as Benn continued to write, is its straight-forward precision in making and arranging observed detail, as well as its economy of action, all of which seem part and parcel of a tonal restraint that saves the scene from melodrama. The poem’s real shock lies in the calmness of the narrator—a calm that has ironic distance in it, but is not without undercurrents of empathy. Like all of Benn’s work this early poem has a sort of double-vision. In Hoffman’s masterful translation, Benn makes us aware in the very first line of his utterly physical sense of the human body—“hoisted onto the slab,” this corpse is as thingy as the cargo the living drayman must have hauled. The verbs and nouns all have a matter-of-fact tangibility that avoids exaggeration, but the spare exactness of description somehow turns the physical gestures of the speaker and the plotted scene itself into a sort of ritualized activity. The speaker’s very alertness to what he is doing implies respect of an almost primal sort for the body.

“Little Aster” has the clinical detachment of the doctor that Benn was—a clear-eyed, discomfiting, anti-Romantic sense of what a body is made of, and what happens to it once its purpose is finished—but no matter how sardonic the poem’s final exclamation is, I’ve never felt more certain than I do in Hoffman’s translation that a kind of spell of departure has been cast, a primitive, raw performance with a hint of the shamanistic about it. Benn is both utterly cold and utterly caring, a world-class pessimist and cynic with tenderness and longing still partially intact. No wonder Hoffman calls him “both the hardest and the softest poet who ever lived.”

In his intro, Hoffman reduces Benn’s biographical character to this somewhat tongue-in-cheek summary: “the military man, the doctor, the poet, and the ladies’ man.” True enough to the facts. Benn was born into a minister’s family in a small village between Berlin and Hamburg in 1886, had completed his medical training by the time his first book came out in 1912, and served in the German army during WW I (he once wrote that he’d served his duty in Brussels, as “a doctor in a whorehouse”). On mustering out, he went into practice in dermatology and venereology. His first wife, from whom he was separated, died in 1922, and a Danish couple subsequently adopted their daughter. By 1935 Benn had reenlisted, driven apparently by a combination of financial need and a sense that a garrison might be the place he was most comfortable in life (“Nothing so dreamy as barracks!”). By 1938 he had remarried, a marriage that would last until 1945, when his wife killed herself, fearful of what might happen to her once the advancing Russians arrived. Another marriage followed WW II, at which point Benn was living in West Berlin, where he remained until his death in 1956. The occupying Allies forbid publication of his work immediately following the war, because of his perceived Nazi sympathies; but a Swiss publisher, Arche, issued Static Poems in 1948, with a Collected Poems arriving in 1956, the year of his death at 70. In between, in 1951, his work had won him the Georg Buchner Prize, one of the two most important literary prizes for writers in German. Neither publication nor prizes seem to have afforded Benn anything resembling a comfortable life.

Of Benn’s brief, troubling travels on the edges of the Nazi orbit in 1933-34, Hoffman has a number of interesting things to say, none of them in defense of Benn exactly, more in scrupulous accounting for how this “fleeting appearance of compatibility” might have come to pass. In any case, as Hoffman points out, “mutual detestation” set in quickly. Benn was first deleted from the medical register as a suspected Jew; then in 1938 he was banned from writing and publishing altogether, his work labeled “degenerate” for its expressionist elements. That work—as Hoffman is at pains to point out—is so pessimistic about human life in general as to make political ideologies like National Socialism seem fraudulent by implication: to Benn “human existence was futile, progress a delusion, history a bloody mess, and the only stay against fatuity was art, was poetry.”

If you are unfamiliar with Benn’s work, and think that last sentence sounds hyperbolic, be assured that it is not. Not at all. Benn makes such notable cynics as Catullus or the Japanese Zen master Ikkyu or the misanthropic Philip Larkin sound like village good folk with relatively sunny outlooks. In American poetry of the last fifty years, perhaps only Alan Dugan or Frederick Seidel (in their very different ways) come close to such a dark estimate of human behavior. That Benn was inclined by psychological character toward such a view is outweighed by the fact that life gave him plenty of grim evidence to confirm his pessimism. That he wanted to make this evidence into poetry suggests something not so much heroic as desperate and compellingly mysterious. There’s little solace in Benn’s work, but there is plenty of an endangered (and endangering) sublime.

If the early work sometimes feels as if it’s straining for an effect, it is no less bracing for its honesty. Immersed in body knowledge, it possesses certain formal gestures that intensify Benn’s raw physicality, gestures that he would develop and use later in his career to build complex collages of image and statement—in particular, a telegraphic style of sentence-making that emphasizes his clipped and fragmented sense of personal observation. As a result, the voice has a terse manner that is both nervy and incisive. The opening of “Night Café”—a poem that owes a debt to Rimbaud’s “To Music”—brings the medical man’s eye to a common social scene:

824: Lives and Loves of Women.

The cello takes a quick drink. The flute

Belches expansively for three beats: good old dinner.

The timpani has one eye on his thriller.

Mossed teeth in pimpled face

Waves to incipient stye.

Greasy hair

Talks to open mouth with adenoids

Faith Hope Love around her neck

Young goiter has a crush on saddlenose.

He treats her to onetwothree beers.

Benn’s writing is living proof that description always reflects attitude—behind these words and images is an acerbic, knowing speaker who may be one of the most laconically fierce creatures in all of world literature. But not just. The ending of the poem shows that other current that ripples through Benn: a susceptibility to lyric intoxication, especially in the presence of women and flowers:

The door melts away: a woman.

Dry desert. Canaanite tan.

Chaste. Concavities. A scent accompanies her, less a scent

Than a sweet pressure of the air

Against my brain.

It really is remarkable the way the metaphorical transformations and rhythmic shifts communicate the young Benn’s physical intoxication here. (And like a lot of early Modernism, one feels what might be the syntactical influence of cinema at work, the editing and framing lessons already available in silent films.) Then Benn does something that also turns out to be prototypical for his work: he undercuts the longing, compromising it with this final observation: “An obesity waddles after.”

The snapped speech; the quick-cutting method of sketching a scene; the physicality (both raw and lyrically intoxicated); the richness of diction, precise and energizing but never decorative or fussy—all of these amplified as Benn developed, especially in the 1930’s when the work evolved a more digressive, complicating movement, ranging more widely over time and space. He never, ever loses his physicality and quickening energy, or his inventive phrasings. His patented mix of erotic longing, calm pastoral alertness, and hardboiled cosmopolitan outlook only intensify:

…the park,

and the flower beds

all damp and tangled—

autumnal sweetness,

tuffets of Erica

along the Autobahn,

everything is Luneburg

heather, purple and unbearing,

whins going nowhere,

introverted stuff

soon browned off—

give it a month

it’ll be as if it’d never flowered.

(“Late”)

And this, from another poem of the 1950’s, called “No Tears”:

Roses, Christ knows how they got to be so lovely,

Green skies over the city

In the evening

In the ephemerality of the years!

The yearning I have for that time

when one mark thirty was all I had,

yes, I counted them this way and that,

I trimmed my days to fit them,

days what am I saying days: weeks on bread and plum mush

out of earthenware pots

brought from my village,

still under the rushlight of native poverty,

how raw everything felt, how tremblingly beautiful!

During the Second World War, and after, Benn increasingly found ways to let his thinking/feeling consciousness expand out of the originating scene, in poems both long and short—without conclusion or solution. Unlike so many poets, he doesn’t seem to feel that he’s here to solve a problem, either for himself or the reader. The later work becomes more epigrammatic in intelligence (“aversion to progress/is profundity in the wise man”) and stoically self-knowing (“my compulsion to shadows”) and, at the end, more generous and tender (“it’s only the ephemeral that is beautiful”). Nonetheless, Benn seems only to have wanted to intensify the contradictory character that lay behind the words, not “cure” his suffering as if were a disease:

Gladioli

A bunch of glads,

certainly highly emblematic of creation,

remote from frills of working blossom with hope of fruit—

slow, durable, placid,

generous, sure of kingly dreams.

All else is natural world and intellect!

Over there the mutton herds:

strenuous ends of clover and daggy sheep—

here friendly talents,

pushing Anna to the center of attention,

explaining her, finding a solution!

The glads offer no solution:

being—falling—

you mustn’t count the days—

fulfillment

livid, tattered, or beautiful.

Most wisdom in poetry feels stagy, self-conscious, but “you mustn’t count the days” is the real thing: a simple, clarifying knowledge that feels earned among the living: the maximum advice, with the minimal exaggeration, given in the face of a terrible sense of meaninglessness, the most literal death threat anyone can imagine. Benn doesn’t have any answer, other than doing his work. He has only his contradictions, and they just lead to questions:

Even now in the big city night

café terrace

summer stars

from the next door table

assessments

of hotels in Frankfurt

the ladies frustrated

if their desires had mass

they would each of them weigh twenty stone

But the electricity in the air! Balmy night

a la travel brochure and

the girls step out of their pictures

improbable lovelies

legs up to here, a waterfall,

their surrender is something one doesn’t even begin

to contemplate.

Married couples by comparison disappoint,

don’t cut it, fail to clear the net,

he smokes, she twists her rings,

worth considering

the whole relationship between marriage and creativity,

stifling or galvanizing.

Questions, questions! Scribbled incitation’s

on a summer night,

there were no Gainsboroughs in my parents’ house

now everything has gone under

the whole thing, par ci, par la,

Selah, end of psalm.

(from “Par Ci, Par La”)

Towards the end, Benn seems to have found some measure of—what? Acceptance? Equanimity? Open-heartedness? There doesn’t seem to be word in English for what comes across in his late poems, the contradictions undiminished, but it has an un-deluded tenderness and compassion in it. A passage from a very late visit to a scene inhabited by characters quite similar to those in the earlier “Night Café” illustrates the change:

Truly, the grief of hearts is ubiquitous

and unending,

but whether they were ever in love

(outwith the awful wedded bed)

burning, athirst, desert-parched

for the nectar of a far-away

mouth,

sinking, drowning

in the impossibility of human souls—

you won’t know, nor can you

ask the waiter,

who’s just ringing up

another Beck’s,

always avid for coupons

to quench a thirst of another nature,

though also deep.

(“They Are Human After All”)

Michael Hoffman’s translations in Impromptus seem by and large flawless to me. He appears to have lived in Benn’s poems for a very long time, and to have a natural affinity for rendering the music of Benn’s German into English. The poems have integrity, in every sense. Hoffman also provides a selection of Benn’s prose—it is every bit a match for the poetry in alacrity, intellect, wryness, passion, honesty, and textured observation. We should be extremely grateful for the whole package.

*

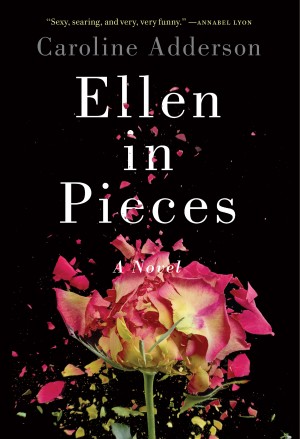

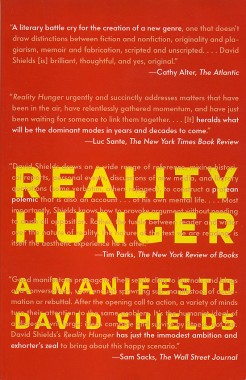

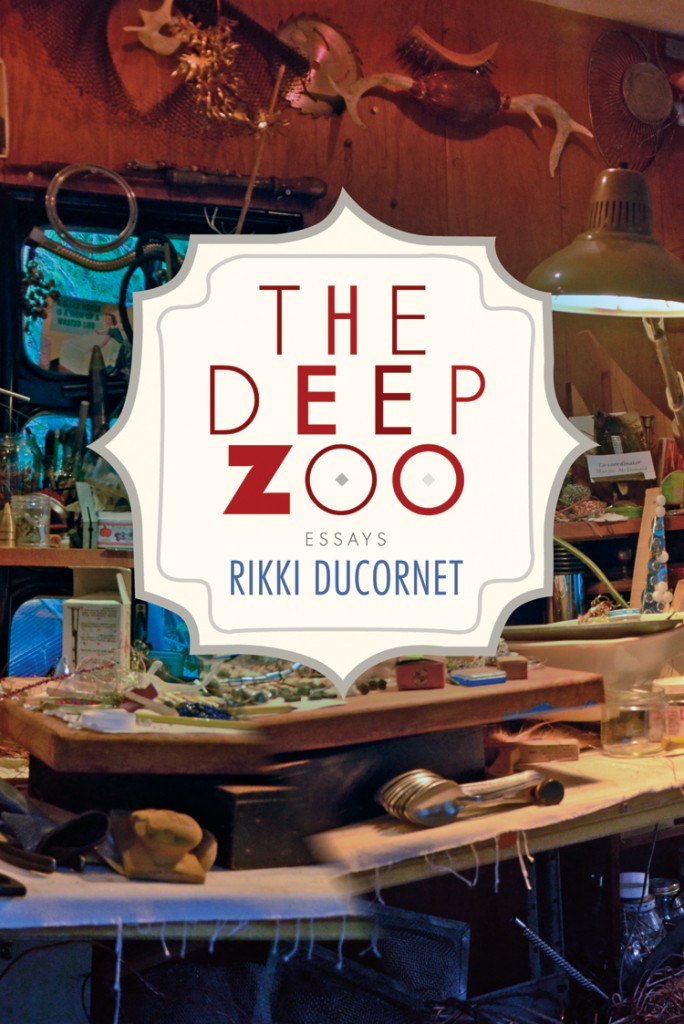

If Gottfried Benn exists for American poets as a village rumor (if he exists at all), Patrizia Cavalli might be said to be a whisper on a windy side street. Prior to FSG issuing My Poems Won’t Change the World in 2013, a small Canadian publisher had brought out Cavalli’s single previous collection in English, a selected poems with the same title that appeared in the late 90’s.

You’d have to have known exactly what you were looking for in order to find that book. Perhaps the only way you might have wondered about her then was if you had read the late Kenneth Koch’s marvelous “Talking with Patrizia,” from One Train. That longish, obsessive, dialogue-driven poem purports to capture a late-night conversation between the two poets, a moment when Koch seeks advice from Cavalli about how to get back together with a woman who has sent him packing.

…I thought

You might be the best

Person to talk to Patrizia since you

Love women and are a woman

Yourself. You may be right Patrizia

Said.

It’s a performance full of Koch’s madcap, bittersweet romanticism, as well as the lively affection of two friends, true believers who are experienced travellers in the land of disappointed longing. In the acknowledgments to the FSG edition, Cavalli reports that she had provided Koch with “technical advice on how to seduce” the woman. She thanks him for his friendship and his longtime support of her work—“if the dead can be thanked.” It’s an aside that typifies the mordant, skeptical wit that runs throughout her work.

Cavalli’s biography is far easier to summarize than Benn’s. Born in 1949 in the small Umbrian city of Todi, she came to Rome in the late 60’s to study philosophy, started writing poems, and fell in with some American ex-pats who introduced her to the Italian novelist Elsa Morante, an early encourager of her work. Her first book of poems appeared in 1974, also titled My Poems Won’t Change the World. Subsequent books have appeared at regular but extended intervals, all from the Italian publisher Einaudi: The Sky (1981), The All Mine Singular I (1992), The Forever Open Theater (1999), and Lazy Gods, Lazy Fate (2006). Cavalli appears to have made a living in Rome as a translator of plays by Shakespeare, Moliere, and Wilde, as well as from her poetry and readings, both of which are highly popular in Italy. The editor (and co-translator) of the FSG book, Gini Alhadeff, reports of Cavalli that “once upon a time she used to play poker and sell paintings on the side (or the other way around).” You can take Alhadeff’s comment as her way of signaling Cavalli’s charismatic personal energy, evidence of which abounds on You Tube, where there are various clips of her reciting her poems, not to mention singing in performance with Italian “folk-rock” groups.

Beyond their urbanity and minds saturated by physical sensation, Cavalli and Benn share a manner of detached self-observation more typical of certain European poets than American (Louise Gluck might be its primary avatar here, and, in a more baroque, performative way, Frederick Seidel). There’s shrewdness in this stance toward the self: its calculations allow for moments of romantic, lyric feeling without melodrama or maudlin effect. This shrewdness is linked in both poets’ work to a contradictory quality: beneath the impulsive, improvisational lyricism that fuels the making of the poems are self-conscious intensities of will and character.

In Cavalli, in particular, there is often an attractive note of irritability beneath her impulsiveness—she can be charmingly resistant at moments, in a way that might remind a reader slightly of the early William Carlos Williams. I mean the Williams of “Danse Russe” and “To a Friend Concerning Several Ladies,” among other poems. This irritability—sometimes bemused, sometimes annoyed or exasperated—gives Cavalli’s voice a freshness of attitude: a witty, breezy confidence and curiosity compounded with something darker, more introverted and warily expectant, even anxious. Almost none of Cavalli’s poems is titled, one implication of which might be to signal an impatient immediacy. This goes hand-in-hand with her conjectural assertiveness—I’m not sure I’ve ever read a more decisively speculative or conclusively ambivalent poet.

The short poem that begins the collection and gives it its title provides a perfect example of this utterly considered but quick-witted responsiveness:

Someone told me

of course my poems

won’t change the world.

I say yes of course

my poems

won’t change the world.

As in so many of Cavalli’s poems, one comes away refreshed by how the speaker—with a simple, almost Zen-like flip—has turned the situation inside out. The shift in tense from past to present, and the slight relining of the phrases, generate a surprising power and adamancy, a vocal inflection at odds with the overt statement: a big, complex “so what?” The implication being that Cavalli has a lot more on her mind than changing the world.

Early and late, Cavalli’s great subject is how we live inside our expectations and desires, endless as they are, entertaining and tormenting, so determinant of our psychological character, but necessary as well for breaking out of our bounded selves.

But first we must free ourselves

from the strict stinginess that produces us,

that produces me on this chair

in the corner of a café

awaiting with the ardor of clerk

the very moment in which

the small blue flames of the eyes

across from me, eyes familiar

with risk, will, having taken aim,

lay claim to a blush

from my face. Which blush they will obtain.

(translated by Geoffrey Brock)

The combination of romance and self-irony on display here is a Cavalli trademark, one that finds expression in all of her work through perceptual inversions and reversals of perspective. Alhadeff writes in her introduction that “innocence” is Cavalli’s main preoccupation—it may be that what she is referring to are moments when Cavalli feels free of those boundaries (the “strict stinginess”) that make the self. It’s an ongoing struggle in her work, an irresolution signaled by how frequently—as here—the poems seem to begin in medias res. There’s a drama in the swerving of her syntax as it flows through the elongated first sentence, a drama that’s underlined when she cuts back against the fluidity of the first sentence with the much shorter, punchier second one. It’s one of Cavalli’s prototypical moments of speculative imagination, built out of guesses and notions, but strangely adamant despite being suppositional. Even the “we” form of address adds to the vibe here, adding a projective ambivalence—it seems both a more general reference to the reader and a way for the speaker to talk to and about herself.

For a poet as physically and psychologically intimate as Cavalli often is, she rarely seems autobiographical or confessional. She is, for example, quite matter-of-fact in the poems about being a lesbian, but at the same it could hardly be said to be the foregrounded subject. There is something compellingly oblique in the elliptical way this poem develops from the scene it renders, with so much information and context left out:

Eating a Macintosh apple

she showed me her crumpled lips.

And afterwards she didn’t know what to do

she couldn’t even discard

the small mangled thing that more and more

turned yellow in her hand.

And daylight’s the time to get drunk

when the body still waits for surprises

from light and from rhythm,

when it still has the energy

to invent a disaster.

(translated by David Shapiro with Gini Alhadeff)

The first stanza is quietly astonishing. With its vibrant, precise handling of physical detail, it’s almost Chekhovian in the way it renders both the character’s physical presence and the speaker’s psychology. The second stanza works just as indirectly, its implications created via a commentary that seems to be located in the present moment of the speaker’s mind, not in the narrative moment of the past. It combines a playful wit with the darker, more implicating knowledge that arrives from experience. The same, thrilling sense of nuance exists in all of Cavalli’s work.

Cavalli is most interested, as she writes in one poem, in “a dallying in the possible,/suspended between too/little and too much, but/always out of place.” The fluidity of her poems is almost the opposite of Gottfried Benn’s more angular, abrupt, and hacked out movements through juxtaposition, but both are masters of changeability, driven by impulsiveness and irritability. Admittedly, Cavalli often comes off as more spirited than Benn. Hard to imagine very many poets who would begin a poem, a complaint about the singularity of identity, like this: “Chair, stop being such a chair!/And books, don’t you be books like that!” But there is also in Cavalli’s work a bracing self-honesty and a fearlessness about putting on display some of the less attractive parts of speaker’s ego—it’s rather wonderful how matter-of-fact she is about this too, without an ounce of phony piety or regret, managing to be charming at the same time she is brutally direct about her own carelessness and contempt at such moments, before giving way to a vulnerability all the more convincing because not overcooked or dramatized.

I walked full of myself and very strong

crossing the bridge disdainfully

tough diamond

sculpting the looks

taught tight black cruel

why should I care, I told myself, and you,

don’t you dare even touch me!

Behind two crazy old women I slowed down

and overtaking one discovered myself

between a woman weighed down by talking

and another silently walking.

Then with untouched fury I went forward

past those lost lurching impediments.

Suddenly a girl appeared

at the streetlight across from me—a beggar.

One in front of me, the others behind,

the light wasn’t green so I looked at them.

I complicated my sight. I was in the distance,

but weakness made my legs go white.

(translated by David Shapiro with Gini Alhadeff)

Something like a phenomenological reduction, a “bracketing,” takes place in moments like these—a witnessing of consciousness, with a suspension of judgment. Fortunately, Cavalli’s wit, often a byproduct of her obsession with romantic love, makes her work something other than a phenomenologist’s dry digest. As she writes of desire at the end of one poem, “it’s the remedy that makes the illness.” For Cavalli, this paradox is rooted in the body at some cellular level:

… But in me physiology

still reigns intact, and forces me to dream:

the cure: an offer of endorphins

from you who are my pusher.

… Why should one want you

for a remedy? Why if your lips

part when, lying down, you opt

for the good and in double vowels say

I love you, no longer proudly chaste but

all absorbed in drinking up my fervor,

why does my blood decide to flow then

harmonious and smooth along the veins

carrying honey to my orphan head.

(from “The sky is blue again today,” translated by Gini Alhadeff)

As with so many Cavalli poems it’s hard to say if this scene is happening in reality or is being imagined by the speaker. The “real world” and the imagination tend to work on each other as reagents in her poems. The subsequent chemical reaction produces a lot of torque in either direction, an energy that is sometimes densely figurative, though oddly fluid, mercurial in temperament—her syntax surging in the direction of whatever surprised space of insight or feeling opens up.

Cavalli’s marvelous syntactical energy, with its steep changes in perceptual scale and altered perspectives and its sudden bursts of metaphoric radiation, are largely rendered successfully into an American idiom by the extended group of her translators, an estimable bunch that includes Mark Strand, Rosanna Warren, Kenneth Koch, Jorie Graham, Judith Baumel, J.D. McClatchy, and Jonathan Galassi, besides Alhadeff, Brock and Shapiro. Occasionally, there are missteps and infelicities in this effort, and one wonders if these might have been avoided under the consistent work of one hand. These missteps seem to occur when the translators try to stick slavishly to the original Italian. “I those isotopes don’t want to drink/my thyroid I do not want to lose” is just awkward sounding in American English, regardless of how close it comes to the syntax of the Italian idiom. Luckily, this kind of thing is rare in My Poems Won’t Change the World, and shouldn’t stand in the way of anyone reading Cavalli’s fresh, nuanced, energizing work—like Benn’s, her voice implicitly challenges the complacencies of American poets. It has been almost thirty years since the last poet in translation to have a widespread effect on American poets: the Slovene Tomaz Salamun. Given a chance, the work of Gottfried Benn and Patrizia Cavalli might have just as strong an influence, at a moment when we could surely use it.

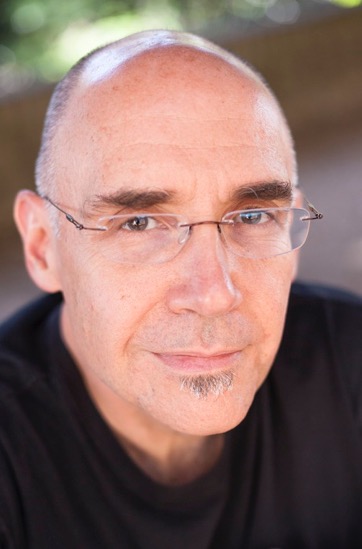

—David Rivard

.

David Rivard’s new book, Standoff, will appear from Graywolf in early 2016. He is the author of five other books of poetry: Otherwise Elsewhere, Sugartown, Bewitched Playground, Wise Poison, winner of the James Laughlin Prize from the Academy of American Poets and a finalist for the Los Angeles Times Book Award, and Torque, winner of the Agnes Lynch Starrett Poetry Prize. Rivard’s poems and essays appear regularly in APR, Ploughshares, Poetry, TriQuarterly, Poetry London, Pushcart Prize, Best American Poetry, and other magazines and anthologies. Among his awards are fellowships from the Guggenheim Foundation, the Civitella Ranieri Foundation, the National Endowment for the Arts, and the Fine Arts Work Center in Provincetown, as well as the Shestack Prize from the American Poetry Review and the O. B. Hardison Jr. Poetry Prize from the Folger Shakespeare Library, in recognition of both his writing and teaching. Rivard is currently the director of the MFA Program in Writing at the University of New Hampshire.

Michael and Kate

Michael and Kate

David Harvey via Wikipedia

David Harvey via Wikipedia

Roger Weingarten

Roger Weingarten