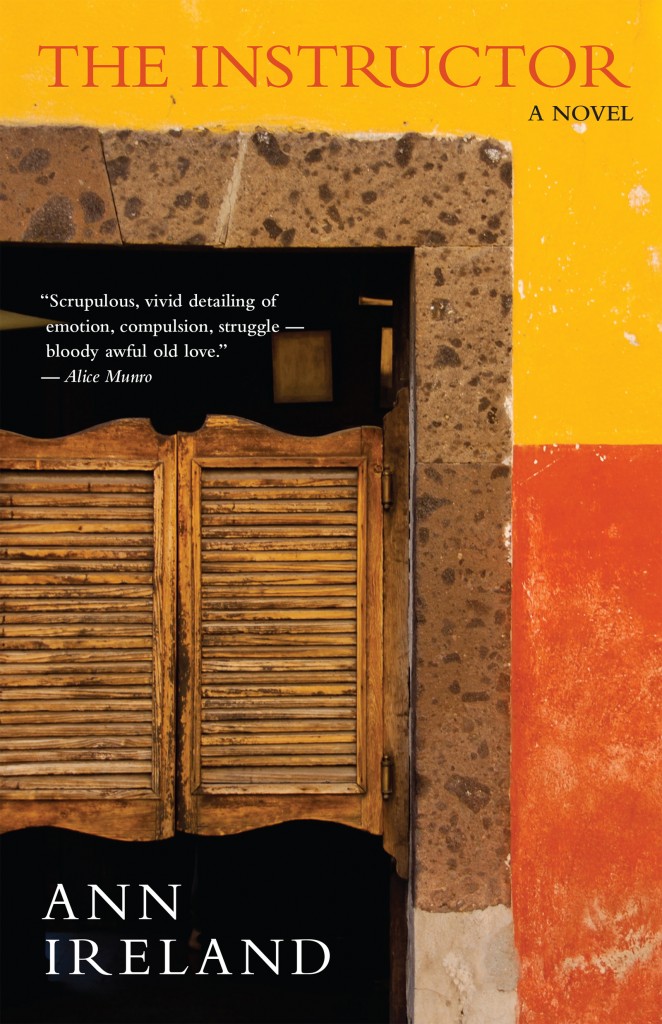

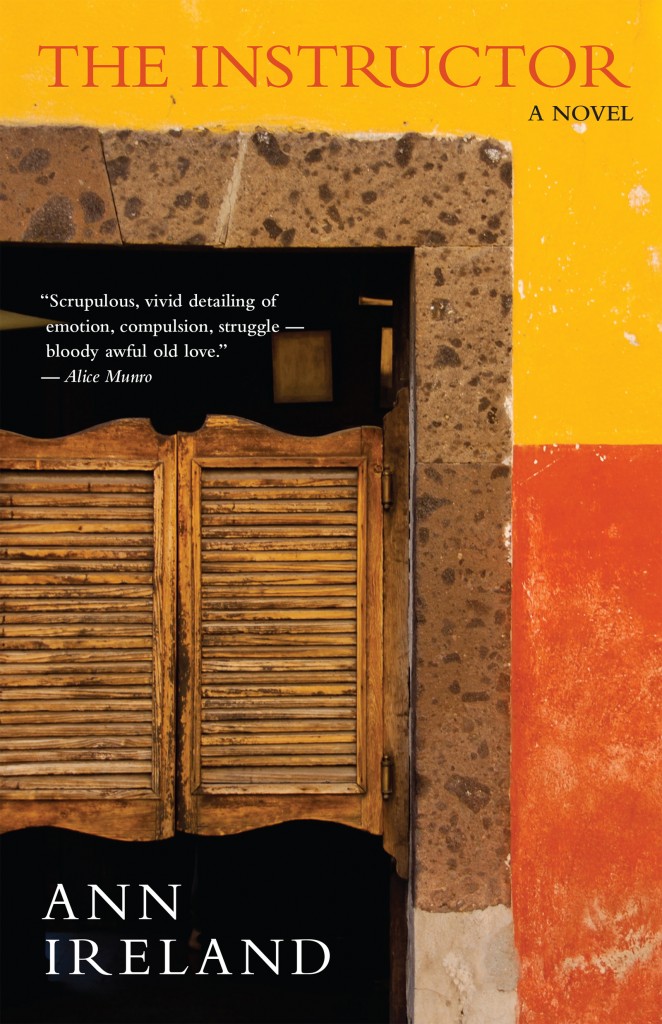

Part way through the opening chapter of Ann Ireland‘s novel The Instructor, the narrator remarks that her putative lover (and art teacher) is like “a scout for some enemy camp, logging facts for a future ambush.” To me, this is about as exact a description of love as I have ever come across. La-de-dah romantics tend to ignore the fact that two people are distant countries, speaking foreign tongues, and that the progress of love is a sort of invasion that is always followed by hasty translation, colonization attempts, power struggles, and, often, retreat. Alice Munro, who wrote the jacket blurb for the novel, gets the picture. The Instructor, Ireland’s second novel, has just been reprinted by Dundurn Press, and we have the honour of publishing the first chapter here for the occasion. The novel tells the story of how 19-year-old Simone Paris falls for her much older art teacher, Otto Guest, on the first day of classes — and what ensues. Ann Ireland is a sophisticated observer of human affairs (of all sorts), and she is deceptive: she tells a good story, sure enough, but she also eschews relationship stereotypes by drilling into the complex undercurrents and finds uneasy answers.

dg

—

Chapter One

MY DEAR OTTO:

See my hand shaking like crazy? It’s not because I’m scared, not in the least. Though two hours ago I was so damn nervous and fidgety I scurried to the outhouse every ten minutes, then worried you’d choose that instant to roll up the hill. There I’d be, popping open the door of the little pagoda, while you leaned against the door of your car, grinning.

I jammed crackers in my mouth, thinking I needed the salt.

Why was I in such a state?

After all, you were history.

The phone call had come out of the blue. “Let’s have tea, just the two of us,” you said, your voice so low and intimate I glanced over my shoulder just to make sure you weren’t standing there.

My own voice, when it found itself, was guarded.

“Late afternoon is best. I’ve got meetings.”

That sounded important.

It is important. We’re running through the slate for next year’s program and I’ve been fighting for that New Music trio to be given the residence position.

“Why do you want —” I said, too late, into the dead phone. As was your habit, you’d hung up without warning. I was shaking then too … for this was my chance to show you what I’d become, how I’d devised a life of my own.

To begin with, the vehicle was all wrong. Come on, Otto, a brick-coloured Honda? It had to be a rental.

When you slipped out of the car, legs first like some starlet, I let out a sigh. For it was you, in the flesh and life-size. You strolled up the dirt path jiggedy-jog, legs bent at the knees, hands thrust deep into your pockets, so loose-limbed I swore you were about to keel over. Your face, grinning widely, so sure of its welcome, grew bigger and bigger — and still I didn’t move a muscle. I was nailed to the position I’d decided on since yesterday’s phone call: arms crossed, back sloped against the doorjamb of the cabin, wearing a black tank top that bled into the darkened interior. Like some Walker Evans photo, I decided, most of my hair drawn back with an elastic, the rest sweeping over my face in the lake breeze.

“Very nice, Simone,” you nodded, missing nothing. A cigarette dangled from your lips. I let you come right up until our toes touched.

“Hello, Otto.”

Of course we embraced, though perhaps a little stiffly. My face got buried in the base of your neck and it seemed to me I’d spent a lot of time gazing into the hollow of your throat where the pulse tapped silently. My fingers curled around the cloth of your collar — threadbare, soft denim — and I was whisked without warning to the hill outside San Patricio: hard earth and scrubby cactus, burros grazing. The heat and dryness made our skin crack and fissure, mimicking the landscape. We’d hiked all afternoon toward the peak where the cross stood, passing only gruff men in straw hats tending goats, then, as we neared the top, no one at all. It was your idea that we couldn’t look down till we reached the summit.

“No cheating, Simone.”

You wanted the vista to hit us in one overwhelming stroke — no dribs and drabs, no gradual seeping in. I scrambled up ahead the last few feet and touched the wooden cross, then turned to look. I felt myself teeter toward the land, which rolled out in all directions, a vast tanned skin of parched mountain and plain declining toward the horizon in minute gradations of brown. The town, with its clay roof tiles, sprawled up the walls of the valley. The sounds were more precise in distance, less cluttered by our own noises: dogs yelped and howled in the endless loop of call and response, while ancient buses groaned up the hills. A woman was calling to her children, her voice spinning effortlessly through the miles of open space. For once I forgot you were there until suddenly your arms swooped around my waist and tugged me in: this same shirt, I swear, my eyes batting against this hollow of a throat.

“I would hardly have recognized you.” You reached up and pulled off your cap, regulation New York Yankees model. Your hair, always bushy, had been flattened, and when you ran your hand through it I saw extra streaks of grey.

“Come on, Otto, it hasn’t been that long.”

“Four or five years.”

“Six, actually.”

“Really?” You seem genuinely astonished. “You look fantastic.”

I had to smile.

Of course you’ve got twenty-five years on me — and look it. What’s happened to your eyes that used to be so clear and sharply focused? And I have to say this, Otto, your jawline is starting to ripple toward the neck. You seem thinner, more brittle, though I felt the little pot belly when our bodies pressed together. An unexpected squish.

“I look like hell, I know it.”

“I wasn’t going to say that.”

“But you were thinking it, dear.”

Dear. That rankled.

We continued to stare at each other, you jiggling change, me stock-still. And I thought, nothing’s happening. The butterflies that had been charging through my stomach all morning seemed to have been drugged. Do you understand what I’m saying, Otto? You stood a foot away and I felt a big fat zero.

“Going to let me in?”

“Of course. Sorry.”

You pushed past and I let you poke around the cabin, lifting objects off the mantel: the cracked coil pot, an Indian basket, the black-and-white photo of Father digging the outhouse hole. The woodstove received special attention, and you lifted the burner and peeked inside. I wouldn’t have been surprised if you’d reached in and touched the ashes, but you just looked, as if deciding whether I’d chucked something in there to burn. After, you strolled past the coffee table, picked up the book of feminist film criticism, flipped through, and I got the distinct impression you knew it had been selected for display. My cheeks heated up. Your hand swept over the tops of chairs and bookshelves, leaving streaks of shiny wood. Why did I feel you were a scout for some enemy camp, logging facts for a future ambush? I stiffened; the nervous feeling kicked in again. It was almost a relief; this was how I expected to be with you.

I decided to make tea and handed you the kettle so you could fetch water from the outside pump.

“This place is great!” you enthused on your return. “Your dad made it?”

“With my mother.”

“It’s like …” You tilted your head. “The house where the seven dwarfs lived. A cartoon cabin.” You hunched under the door frame. “Bet your old man is exactly five foot six. Everything’s scaled to that height.”

Right as always.

I found of box of lemon biscuits and tossed them on the table. You began to make short work of them, knocking two at a time into your hand, while crumbs scattered down the front of your shirt.

“Where’s your mother now?” you said, dropping onto a chair.

“She moved into a condo in Etobicoke. Nice view of the lake. She loves it.”

“And your dad?”

“He died three and a half years ago.”

“I’m so sorry.” You winced and briefly shut your eyes. “I didn’t know.”

“Of course not: how could you?” I pulled away from your reaching hand and watched you swing your legs so you could follow my movements around the room. You didn’t speak, and I knew you were hoping I’d say more about him. Your face waited, creased in sympathy. I measured tea into the Brown Betty pot and rinsed out two mugs. I collected the plastic honey jar from the shelf, then poured milk into a tiny pitcher. I would not give you this chance to pry me open. The spoons received a quick wipe on the towel.

You watched each gesture avidly.

“Then will you at least tell me what you’ve been doing with yourself?”

I let out a breath, staring at the back of my own hand as it closed over the teapot handle. You could still do it, make me achingly visible to myself.

“What do you want to know, Otto?”

“Everything. The works — every second since you left me.”

“You think I’ve been writing it all down, waiting for the day you’d turn up again?”

You smiled quickly. “Haven’t you?”

I flushed, because in a way I had. Lived my life and at the same time wondered what you’d make of it, anticipating your comments, your chuckles, and of course, the withering asides that had the effect of turning whatever I was doing — or whoever I was with — into something faintly comical.

“Well?” You leaned forward, following the motion of my fingers as they wrapped around the copper tray. “There must have been plenty of men sniffing around.”

You wanted all the details, fixing me with your eyes until I’d find myself describing the colour of the sheets, the texture of skin and hair. I set down the tea tray, the smell of Earl Grey a consoling presence, and pulled up a chair.

“Anyone serious?” you persisted.

“What’s this all about, Otto?”

“Curiosity.”

“Is that all?”

You hesitated only a second. “Of course.”

I stared into your face looking for signs: irony, amusement … but could read only the wide-eyed innocence you’d chosen for display.

I could tell you about Raymond, the dancer — but stopped just as I saw the edges of your mouth tighten. Already I was turning Raymond into a story, a series of tiny tropes to make you howl with delight and commiseration.

I shook my head, half laughing at my narrow escape, trying to shake that eager stare, at the same time bathing in its intensity.

“No, Otto, it’s my turn.”

“Your turn?”

“That’s right. My turn to ask questions.”

“Ahhh,” you exhaled noisily and pushed your chair away from the table. You lifted your chin toward the window and a glazed look came over your face that I instantly recognized: the Shift. The moment of withdrawal. Suddenly, with the practiced move of an old-time actor, you launched, full-tilt, into a monologue.

Something about light refraction that you’d read in a scientific journal. “Great diagrams, and a nice sequence of time-lapse photos …” Your legs splayed and you crooked an arm over the back of the chair.

The room shrank.

“… This guy’s theory knocks away all our notions of how we see, how our eyes gather and process light.”

I was supposed to lean into every word.

Instead, I gazed at you in amazement; you’d known, hadn’t you, exactly what I’d been about to say? The more you blabbed, underlining every third word with your finger on the tabletop, the sadder I felt.

And I was bored, Otto.

That was a first.

“… So you just change the angle of dispersal.” You hiked a cigarette from the package and positioned it just so on the table. “What appears to be pigment is really nothing more than mirrors!” You giggled with delight.

“Otto —”

“Think what could be done —”

“Ot-to —” singing it now like “Yoo-hoo.” Nervy. You weren’t accustomed to being interrupted in full flight.

Finally you tugged your gaze away from the open window and looked at me.

“I want to know why you’re here.” I was proud of that, the simple declarative statement.

Our stares hooked for an instant, then, incredibly, you drop-ped right back into the soliloquy as if I’d never uttered a word.

“… bombard them with photosensitive materials …”

I saw exactly what was going to happen, how you’d leave with nothing said and that it would drive me crazy and I’d spend the next six months berating myself, reconstructing the scene. So I pushed my chair back and brazenly set my face close to yours.

“Why are you here, Otto? Don’t natter on about goddamn light refraction — mail me the article!”

Your cheek muscles worked up and down. Your stare was flat, as if you were overhearing some foreign language. Then you chuckled, flicked an ash off your cigarette, and said, “You haven’t yet told me what you’ve been up to.”

You weren’t going to be snared by an amateur.

“It’s been six years, Otto.”

“So work backwards.”

Of course. Time is a fluid concept, its direction determined by a tilt of the glass.

“I’m director of the Summer Arts Festival.”

A quick smile. “Good for you.”

“As of two years ago.”

“Still making art?”

“No time.” I made a dismissive gesture but felt the familiar pang.

“Of course not. You have a real job. Someone has to run the country.”

“It’s a big operation,” I heard myself insist. “We cram two months full of chamber music, author readings, dance performances, workshops, and classes. Our budget’s doubled in two years and most of that is local money.” I sounded like the Chamber of Commerce.

You nodded. Smoke drifted from your nostrils and made its languid way toward the ceiling rafters. You were enjoying this. And why not? I was right where I had always been: desperate to please and impress you.

“I’m on a roll,” I declared. “They do everything I want. When Krizanc, chairman of my board, starts to rant about ‘market-driven programming,’ I tell him we have to create our audience. Not let the audience create us. Make them drowsy with something familiar — then kick open the gates. Blow them away!”

Who was this talking?

All these years of careful filtering, reclaiming my voice — and now this: the mimic reborn.

Late-afternoon sun pressed through the window and I leapt to tug the curtain. “It’s all in the presentation. Make them think they’re on the cutting edge right here in Rupert and it becomes a point of pride. They expect art to be tough; they want it to be.”

Your word, as in “tough-minded,” “tough-thinking.”

“Bravo.” You hooked a chair with the toe of your boot. “Sit down, Simone, you’re very flushed.”

I obeyed, hating the way I felt, overheated and sticky, pulse racing.

“My half-dozen years haven’t been nearly so fruitful.”

I forced myself to look straight into your face. “What have you been doing?”

One of your famous pauses.

“I stayed on,” you said at last.

“In San Patricio?”

You nodded.

“What on earth did you do there for six years?” I was shocked; it never occurred to me that you might have stayed on. All this time I’d been walking down Spadina Avenue in downtown Toronto every chance I got, glancing up at your studio window, wondering if you were in there with your ripped-up magazines and glue stick.

“Got drunk most days. Made a truckload of bad drawings. Then one morning I got sick of the sun and the smell of rancid cooking oil and started to drive north.”

“And?”

“That’s it.”

“What about your ex —”

“Wife? Carmen’s out of the picture, except where Kip is concerned.”

Your son. He’d be twenty-one by now. Older than I was when I stepped on the plane to come home. “What’s he up to?” You always loved to talk about your son.

Your fingers wrapped around your teacup, the nails chewed to bits. “I saw him this morning. Not so good, Simone. Not so good.”

I stared.

“They’re adjusting his medication. Makes him screwy, his equilibrium is shot. The kid can hardly walk.”

“Medication? What are you talking about?” My self-consciousness vanished.

“He gets seizures.” Your eyes scanned the room without focusing. “It began five or six years ago. Of course, you’d have no way of knowing.”

“What kind of seizures?”

“He goes months without any problem, then suddenly, keels over wherever he is: the gym, a crowded subway.”

“Jesus, Otto, I had no idea.”

“Of course not.”

“It doesn’t have anything to do with” — I struggled to sound casual — “that time he fell off the boat?”

“What?”

You sound genuinely mystified.

“In San Patricio, on the lake.” I prodded, already wishing I hadn’t brought it up.

You stared at me, fully engaged for a few seconds. “I don’t see how. He wasn’t under more than a minute.”

Right.

“The worst of it isn’t the seizures,” you went on. “Which happen maybe three, four times a year. It’s his attitude that stinks. Yesterday, at the hospital, he made his neck go all floppy, then titters, ‘What a shame your kid’s a crip.’ Crip my ass!”

The table shuddered as you smacked it with your hand. “Ninety-five percent of the time he’s perfectly okay. There’s guys a lot worse off than him — blind! Imagine being blind, or deaf! But you don’t see them hanging out on Queen Street, playing skinhead, cadging cigarettes and spare change. He snorts PAM out of a goddamn baggie …” You took a deep breath and snapped open the top of your shirt. “He’s quit three schools, got caught boosting a pair of Doc Martens from the Eaton Centre …”

Had you driven two hours to spout off against your son, ask my forgiveness for being such a lousy father?

“I’m sorry, Otto.”

“So am I.” Your tone was aggressive, as if you were determined I’d know the worst of it. “I thought if I stayed far away in some hill town everyone would be better off, that I was so fucked up it would overwhelm them. Pure ego.” You laughed. “Which I’ve never been short of.”

I didn’t deny this. “He lives with you, or Carmen?”

“He’s in a halfway house for kids who screw up. They huddle out on the sidewalk most of the day, smoking, or they’re taking courses in something called ‘Life Skills.’” You snorted. “He asked after you, just as I was leaving today.”

“Me?” My mind was racing.

“He wondered if you were ‘still on the scene.’”

“What did you say?”

“That I hadn’t seen you for years. That it wasn’t meant to be.” Your knee pressed against mine. “He’s convinced you saved his life, that time he pitched overboard.”

I reddened. “That’s absurd.”

“Even so, he likes the idea that you pulled him from the brink.”

“But it’s not true!”

“He thinks it is.”

First your knee, now your thigh. Uneasy, I shifted, but didn’t move away.

You reached for the cookie box and shook it. Empty.

This wasn’t the scene I’d be picturing, far from it.

Hell, I was feeling sorry for you. I’d been prepared for anger — even desire, but not this.

“Sometimes I used to feel you two were conspiring against me.” You spoke with studied casualness. “When you came in from riding those underfed nags, Kip was so flushed and healthy-looking — I used to wish I had that power.”

Power? I had to laugh. So you were jealous, Otto. This notion would have pleased me once. Now I just felt drained. The numbness crept back. Here we were again, using Kip as our topic, and I was supposed to pretend I cared. I reached for the tea things and scraped cookie crumbs onto a saucer.

A long time ago I was reaching for you to tear the world open. Now, in your presence, I felt hemmed in, claustrophobic.

“I need to live in Toronto again, to be near Kip.”

“That makes sense.” I didn’t hide a yawn.

“Last Saturday I picked up the newspaper and who did I see but you — with this most professional smile planted on your face. Very impressive, Simone.”

“You saw that?” I couldn’t help feeling pleased. The Globe had done a feature in the Arts section, underlining how the Summer Festival had “revitalized” the area and pinning much of the success of its “fresh, young director.”

“I thought, She looks so damn competent — pretty too.”

I crumpled the cookie box and tossed it toward the trash.

“I’m flat broke, Simone. Benny says the art market’s shriveled, nothing’s moving, nothing he can do for me.”

Benny — your dealer.

“There’s a recession, Otto. Even in San Patricio you must have heard about it.”

“I need a job.”

“Right.” I still didn’t get it.

“So —” You followed me to the sink with your saucer and cup. “You’re running this nice little festival. You could fit me in, as a teacher, artist-in-residence. I’m flexible as an old shoe, and more to the point, I’m desperate.” A smoke ring escaped from your mouth and hung in the air.

“As a teacher,” you continued, “I’m the best there is. You, if anyone, should know that.”

I dumped the leaves into the compost bowl. Now I understood why you’d come.

“We always got along well.”

I stared, mouth open.

You were jiggling a set of keys: Budget Rent A Car. At least I was right about that. “Think about it. Drop me a line, or call, as soon as you get a moment. I’ve got my old studio back.”

* * *

The little Honda bucked down the hill until its muffler scraped highway asphalt.

Then you cranked your window down and shouted into the hot still air: “You must feel very safe here!”

I opened my mouth to protest — “Who the hell wants safety?” — then remembered: they were your exact words, uttered years earlier.

•

It was a scruffy copy of Lassie Come Home, borrowed from the Rupert Public Library, and as I turned each page my fingers buffed scabs of peanut butter and petrified snot.

I didn’t even notice the sun was falling and I was losing my light. I simply tilted the book a little more every few minutes — until a word stopped my eye mid-sentence.

What was this word?

She.

Lassie, I’d just discovered, was a “she.”

The book dropped between my knees. Lassie, the hero of the tale, was actually a heroine. That was like those other despised words: poetess, actress, cowgirl — images of women in fringed skirts, riding sidesaddle, squealing with terror. How could I identify with the girl version of the real thing? How can fantasy be populated by underachievers?

—Excerpted from The Instructor

Copyright © 2013, Ann Ireland. All rights reserved. www.dundurn.com

———————-

Ann Ireland

Ann Ireland is the author of

four novels, most recently THE BLUE GUITAR, which has been getting excellent reviews all across Canada. She coordinates the Writing Workshops department at the Chang School of Continuing Education, Ryerson University, in Toronto. She teaches on line writing courses and edits novels for other writers from time to time. She also writes profiles of artists for

Canadian Art Magazine and

Numéro Cinq Magazine (where she is Contributing Editor). Dundurn Press will be re-publishing Ann’s second novel: THE INSTRUCTOR over the summer of 2013.