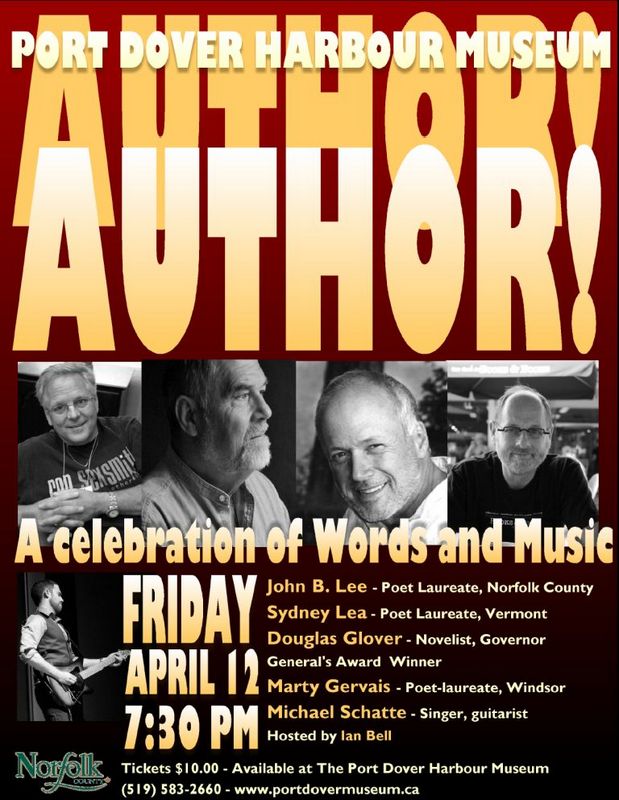

Herewith Joe Milan’s lovely, ever so slightly melancholy portrait of the Seoul he has come to know teaching at the Catholic University of Korea. This is contemporary Seoul, dominated by a priapic, neon-lit tower, the traditional architecture destroyed by war and rebuilt to resemble someone else’s urban dream. What should be his own world is strange to Joe Milan; his life in the city is punctuated by memories of home in America and rumours of war. His Seoul is a complicated place, riven with memory, tradition, absence and paradox. But sweepers shape the piles of raked leaves to look like hearts and the rice cakes his grandmother serves have the scent of pine.

This is the latest in our growing collection of What It’s Like Living Here essays, the 41st in fact. Think of that.

dg

Concrete

Seoul Tower, a tourist magnet in the heart of the city and the best quick way to see the place, reaches into the sky, perched alone on a forested hill apart from the packed clothing shops, red sauce stained food carts and sterile department stores of Myung-dong. In the shade of trees, you huff your way up the winding road. There are heart shaped piles of leaves raked onto the walkway and every few meters piles of rocks stacked beside the path. A young child, biting his lip, totters toward one of the piles with a rock. His mother cheers him on, “Put it on the top and make a wish.” Years ago you did the same. But unlike this child, you tumbled and fell short before the stack.

The tower stabs the sky, a rocket ready to leave the trees and the ancient rock walls behind. For centuries this hill was a lookout. You imagine bored men with long beards and spears in hand staring out to the ridgelines, waiting for the signal fires of incoming invaders. Today’s soldiers stand watch on hills fifty kilometers north of Seoul. They are mostly eighteen and nineteen-year-old boys doing their military service, cursing their fate, waiting for a different sort of fire that would pop and boom and flash and screech and burn.

When you reach the elevator doors it is dark until the walls burst into blue light from hidden projectors in the ceiling. An image of the tower at night appears on the elevator door, back-dropped by stars that you had never seen in the sky in Korea. Lasers write in English “love n tower.” You wonder if they are going for “lovin tower” or “love in tower.”

At the observation deck you’re greeted by an attendant dressed in white and black like a maître d’. She bows slightly–a nod really–and motions you around the half-wall to the windows that surround you. From up here the city is field of concrete buildings and glass towers rising and falling toward the river: the Han River. You are not sure, but it could mean the “One River,” or the “Korean River,” or even the “Suffering River,” but your Korean isn’t as good as it should be. The river is a bluish crack between the two halves of gray city. Crisscrossing veins of tight alleyways wrinkle the city, hold the city together with backstreets wide enough only for scooters loaded down with TVs and tin boxes of cheap Chinese food. Alleyways walled with brick and concrete branded with random acts of paint that always seem to morph into the same dull gray. This gray, like fog smothering and hiding a hillside, is the Seoul you remember from your childhood visits.

But this isn’t the same city. Speckled in the gray are wide highways and glass towers and miniature red brick boxes that litter the gray field to the base of white stone mountains wrapping the city. Your eyes trace the spine of the mountains where, long ago, tigers cloaked by the black of night, crept down and preyed upon the villages clustered just outside of the city walls. Now on those same peaks blasé hikers dressed in florescent pink and blue Gortex drink rice beer and eat savory pancakes.

You think of the mountains of your life in America, the jagged knife edges of the Cascades and the Olympics: young and bold mountains skirted in a shag of green. These mountains in front of you have spots too ragged for the trees where the naked rock shows white. The new concrete poured over cracks in the alley by your apartment, yet to turn gray from the rains, is white, too. The rains leave trails of gray streaks clinging to the cracked corners of windows and the bars that guard them. You think about the concrete your father taught you to pour. When you rushed, didn’t let it settle right, tiny fissures and wrinkles broke to the surface. He would shake his head as his finger traced the cracks and say, “Haste makes waste, boy.”

Here, in Korea, elderly faces speak of decades of haste.

Have you eaten?

You finger the stenciling on the window in front of you. It reads 9,596.52 Km to Los Angeles. Seattle is in the same direction, though not as distant. You remember the cold damp air coated in the smell of pine and cedar. Below the tower, to your surprise, are green blotches dropped in the gray field: parks. They’re newer, brighter, than the growth on the mountains. This is where old men in Member’s Only jackets, hunched over lacquered wood boards tattooed with black grids, play Go. They argue over where the next white or black game piece should go. Old women gather in the parks, too, chatting while they unpack their foiled rolls of seaweed and rice: Kim Bap.

The other green blotches are the palaces with tree lined parade grounds rebuilt for the umpteenth time after the invasions that came every century or so. Out of the rubble of the last invasion, people rebuilt Seoul anew with brick, glass and concrete. They rebuilt Seoul replicating the buildings of the world outside of Korea. The replicas of itself are the only buildings built with wood.

You try to find your apartment, Block 20. One gray lego block among thirty other blocks flanking the glistening steel bowl of World Cup Stadium. Twenty-five years old and already your apartment looks dilapidated. You’ve considered calling a location scout. You would tell them, “Hey man, I got the perfect place for you to film 1984 and you know remakes are all the rage.”

When you open the creaking cold metal door, walk down the half-wall corridor, step into the dark stairway where the lights flicker to life after a few steps, emerge out of the building into the hazy sunlight, and find your way through the maze of double parked cars jamming the parking lot, you see them. The retirees. Beside the first floor windows they crouch over trashcans and styrofoam packing boxes tending their gardens of verdant life. The old men and women are guerrilla gardeners suited up in dirty white gloves and teal visors. They start early in the morning, planting, weeding, battling the gray one clump of vegetables at a time. No one tells them, “You can’t do that” since, they are old. And here, at least for people, age gets respect.

A vine has snaked up three floors of your building, clinging to your window, offering what could be cucumbers, or some knobby vegetable more bent and rugged than anything you’ve seen at the supermarket. Can you take one for a salad, or will a battle-weary old woman come knocking on the door to ask for her harvest?

From the trashcans and styrofoam boxes along the sidewalks, the gardens grow. On rooftops and huddled in demolished housing lots, these gardens grow. But you know this is no green fad. This is memory that is spoken even now in the elderly’s greetings, “Have you eaten?”

Sirens

Yesterday you pushed and swayed and weaved through the currents of people in the subway station and jammed yourself into the subway car. You let go of your briefcase and it didn’t fall to the ground. It floated, defying gravity, hanging with the friction of bodies dressed in suits.

Youthful figures in black, their headphones jammed in their ears, all silently ignoring the chug of train tracks as if this is part of a pact where everyone pretends not to be clutched by the crowd swaying with the train. The flat-screen monitor above the exit doors loops a video about how to use a smoke hood hidden in padlocked glass boxes at the station. There are at least ten steps and you felt like you should take notes. There had been fires on the trains before.

At lunch you heard the sirens. Wailing loudspeakers erupted from their hiding spots on poles painted like trees. Fake branches and leaves shrouded the speaker horns and square boxes. Radio transmitters? Looking out your office window, you saw the cars stop and the sidewalks cleared. You waited for the flashes from a far off ridgeline, artillery fire booming and shells smashing and battering the buildings, dogs howling, fires exploding and engulfing the city then raging and rioting all the way up to the peaks. The office corridor hummed without pause, and you heard someone laughing. You alone, it seemed, wondered of the possibilities.

English

Everything in Seoul Tower is in English. Everything new is tattooed with it. On neon signs jutting off buildings, on the menus in the Korean dive bars serving “pork intestine,” in catchy commercial slogans, and on K-pop tracks that old expats describe–with derision–as nothing more than “nursery rhymes slapped over euro-techno beats.” English isn’t hidden away in the enclaves of black walled of foreign bars of Itaewon anymore. It was in those kind of places you hid after work, always looking for a blank space of wall to add your name in chalk. You hid there with the other English teachers and American soldiers. Those places are gone like most of the people who wrote their names on walls.

In Itaewon, vendors shout in English “we have clothes in your size.” But outside this little corner of Seoul, you force yourself to speak Korean, hesitantly, trying to spit out phrases while gagged by the rocks of verbs and conjugations. In the beginning you motioned and pointed and people would look at you with confusion and ask, “Mwol?” But now, they understand you and applaud you. You can order yourself a coffee. It is something, although your pronunciation is butchered to the point of another language altogether. Being half-Korean doesn’t help. Nor does that feeling of shame whenever you utter that fact and they search your face for something left behind.

You worry that your English is getting worse. With lightning speed, chopped and spliced with slang, you feel lost with your friends in America on the phone. English is continuing without you as each year passes. You are losing your ear for the only language you have while surrounded by a language you should have had.

The concrete house

As you make your way back to the elevator in Seoul tower, you see through an opposite window a fog of buildings climbing a hill in the distance. That’s where your grandmother lives. You know it; its shade of gray is darker and older than the rest.

Next week is Chuseok, an ancient holiday celebrating the harvest and the dead. Your apartment, like the subways, the streets, all the gray city should be empty and cold except for a few stragglers without a hometown or a family to go to. Almost no one is from Seoul. You’ll buy a box of fruits to give your grandmother and you’ll carry it with you on the abandoned subway on one of the few days you can get a seat.

But the night before Chuseok, you’ll gather with your friends and have a few drinks. Someone’s girlfriend will feel bad for all of you. And before she leaves for her own hometown, deep in a dark corner of a friend’s concrete walled apartment, you and your foreign friends–who each have lost a parent to one disease or another–will solemnly stand as she lays out a table with food and empty plates. She will tell you this is a Jaesa: a way to honor the departed family spirits, something many Koreans don’t do anymore.

There will an empty plate set out for your father. You’ll pour liquor into a shot glass and circle it around the incense smoke three times and pour it out into a bowl. Taking a fork, instead of chopsticks, you’ll clang it down three times against your father’s empty plate and rest it on the fried fish dish. You’ll imagine him tearing apart southern fried catfish, the crumbs littering the plate. He had always missed “real catfish from way back down home.” He would say the same here, but maybe the thought will be good enough. Three times all the way to the floor, resting your forehead against your hands, you’ll kneel and bow and breathe deep. Then you’ll walk out of the room so your father’s spirit can eat. You’ll miss your father as you stare at the web of cracks scarring the wood print linoleum floor.

On Chuseok you’ll go to your grandmother’s apartment. The two of you will eat: glassy japjae noodles, chilly red pork, and damp white and green rice cakes filled with sugar and the smell of pine. Afterward, as the sun sets behind the haze, you’ll walk with her through the grayed alleys on cracked pavement. Soon her neighborhood, built forty years ago, will be torn down and buried in memory for newer apartments that too, will crack and gray with the rains. She will say in Korean to her friends that pass by, “This is my grandson. This is my grandson. He came home for Chuseok.”

When you reach the old house that she lived in years ago, built when the concrete buildings were new and clean, she’ll say, “This is where I lived.”

“I remember,” you’ll say.

—Joe Milan

———————

Joe Milan has spent nearly a third of his life traveling and living outside the borders of the USA, and his most recent landing is in Seoul where he writes and teaches at the Catholic University of Korea. Joe is a recent graduate from the Vermont College of Fine Arts .