In poetry, the local is the universal. As William Blake wrote: “To see a World in a Grain of Sand / And a Heaven in a Wild Flower, / Hold Infinity in the palm of your hand / And Eternity in an hour.” John B. Lee is an old friend, published many times in Numéro Cinq, who lives in Port Dover, Ontario, just down the road from the farm where I grew up. We both have a special affection for Norfolk County, to me, always both local and an epic ground, filtered with blood of ancestors (see my anthology of Norfolk County history “A Geography of the Soul“). And in these poems, he remembers a relative of his, Ida Wright, born in Waterford, the farming town, where I went to high school. Ida went to China as a missionary — the rest I will let John tell. But notice, yes, how these poems rise by degrees to compass all life (and beyond), from a southwestern Ontario schoolroom to eternity.

we all share our nature with the dead

one name carved deep in the cave

of every empty desk is yours

and one name there is mine

We have also translations of the poems into Spanish (we’ve done this before as well), courtesy of John B. Lee’s Cuban friend and colleague Manuel de Jesus Velázquez Léon.

dg

The poems in this document are taken from a manuscript in progress called Into a Land of Strangers. The central figure in the poems is my great-aunt Ida Wight née Emerick, born in Waterford, Ontario, and raised by her father and mother in Bothwell, Ontario. After a brief stint as an elementary school teacher in Highgate, she joined the Mission to China and she became a missionary in China in the late 1800’s where she married a fellow missionary. Widowed during the Boxer Rebellion, she and her baby daughter fled on foot along with other westerners, surviving by eating boiled cotton and shoe leather. She spent two years in Canada before returning to China where she became superintendent of missionary schools. During the Second World War, she fled to Hong Kong where she was eventually placed in an internment camp by the Japanese. Liberated by the Americans in late 1944, she traveled to Durban, South Africa, where she remained until her death on January 1, 1952. Her grandchildren were also interned in a camp for the duration of the war. The book Into a Land of Strangers tells the story of three generations of the Emerick family beginning with the German-American late-come Loyalist Francis Emerick who served on the Canadian side in the Lincoln militia during the War of 1812 after which he farmed a farm in what is now Middlesex County in southern Ontario.

—John B. Lee

.

A Person on Business from Porlock

There is an imam

mosqued in the empire of the west

who preaches

that the greatest sin

in the land of the golden mountain

is the American lawn

even the burning earth

of south Texas, even there

on the torpid border of old Spain

that stolen-water-green thing thrives

with a great thickening

of wide-bladed

low-growth St. Augustine grass

even there

in the blue boil

of the unusable summer pools

of suburbia

in that necessary evaporate cool

all along the arroyos

the dry brown rivers

of parched clay

thirsty mud cracking open

like oil on old canvas

in the brilliant mirror of an unreflecting sky

the monolithic malady of modern paradise

insists itself

between the dream houses

of every middleclass mind

if one thinks of Cathay

and the Khan’s palace

in the city of Chandu

where mare’s milk spills

like moonlight on marble

and light falls in chords through cracks

like strands of silk that brace the bamboo palace

where leopards slip the saddle

in let-loose leaps

and the jessed hawks fly

over the claw shade of a shadow-measured wall

as I think now

of my own neighbour

mowing his yard for

the fourth time today

or as it was

with the woman next door

who plucked cut blades

one by one

from the sweet fragrance

of her wet-sock work with a similar care

one might use to pull stray thread

from a new garment

and I also recall

the mad lady nursing lost leaves

at midnight

in the candle-glow under star-dark heaven

when the world is otherwise laudanum black

and behind the forehead

like stones in a deep stream

something sleeps

turning green

.

Una persona de Porlock en negocios

Hay un imam

en una mezquita del imperio del oeste

que predica

que el pecado más grande

en la tierra de la montaña áurea

es el césped estadounidense

incluso la tierra ardiente

del sur de Texas, incluso allí

en la frontera letárgica de la vieja España

esa cosa verde del agua robada prospera

con un gran espesamiento

yerba de San Agustín

de anchas hojas

incluso allí

en el corral azul

de inservibles piscinas de verano

de los suburbios

en ese fresco necesario que se evapora

a lo largo de los arroyos

los secos ríos pardos

de árido barro

fango sediento que se resquebraja

como el óleo en el lienzo viejo

en el espejo brillante de un cielo sin reflejos

el mal monolítico del paraíso moderno

insiste

entre las casas de sueños

de cada mente de clase media

si uno piensa en Catay

y el palacio del Kan

en la ciudad de Chandu

donde la leche de yegua chorrea

como luz de luna sobre el mármol

y la luz cae en acordes a través de las grietas

como hebras de seda que apuntalan el palacio de bambú

donde los leopardos se deslizan de la montura

en saltos sueltos

y los halcones encorreados vuelan

sobre la penumbra desgarrada de una pared medida por su sombra

mientras pienso ahora

en mi propio vecino

cortando el césped de su patio por

cuarta vez hoy

o como fue

con la mujer de la casa de al lado

que recogió las briznas cortadas

una a una

desde la fragancia dulce

de su trabajo de medias mojadas con cuidado similar

al que pondríamos para sacar hilos extraviados

de una nueva prenda de vestir

y también recuerdo

la señora loca cuidando hojas perdidas

a medianoche

al fulgor de una vela bajo un cielo oscuro de estrellas

cuando el mundo está por otra parte negro como el láudano

y detrás de la frente

como piedras en una corriente profunda

algo duerme

tornándose verde

.

The Superintendent

looking at the comfortable room

in the luxurious home

she had built for herself

in the orient

my cousin said

of our late aunt

posing like widowed gentry

lolling amongst her precious things

“I thought missionaries

were supposed to be poor …”

her silk pillows

embroideries

gilt upholsteries, silver

tea service, fine cloth

painted vase, and

exotic

high-buttoned

tight-bodice

dress, the tats

and flounces—doyen

of the wealthy classes

mistress of a private school

privy to

the Sino-Victoriana

of a distant land that changed the mind

like the slow conversion of green

in slanting shade

where everything greys

in the lonesome lamentation of a solitary light

growing older

in a homeland no longer home

in the piano parlour silence

with that deep-toned quiet

of untouched ivory, each key

yellow as a smoker’s tooth

who does not fear

or loathe to hear

the superintendent of schools

with her disapproving

and ultra-grammatical

crepitation, clearing her throat

with a phlegmy “ahem”

from the back of the room

her spine as stiff as a pointer

she strides

her heels cracking the floor

as she seizes the chalk of the day

and with white streak

screeching

is it a sin or is it a dream of sin

to see through the third eye

how the children tremble

shading their work

for a smudge of errors

the grand failures

we feel

in the pedagogical squint

of the once-a-term stranger

in a classroom smelling of spilled ink

and the bass notes of old plasticine

fragrant in bent fingers

and multi-coloured snakes of clay

rolled flat on the modeling board

one name carved deep

in the cave of every desk

for we are the bullied, the shy

the wild, the plump

the brilliant, the lost

the bratty, the eager-to-please

the quiet, the pimpled

the unclean, the poor

the criminal, the crippled, the maimed

the doomed-to-die young

the bad seed, the sniffling, sniveling

easy-to-hate tattle tale

the pampered

the beaten, the bewildered

the too-stupid-for words

learning one lesson in a tall cone-shaped hat

under tousled hair

and one in the tasseled

mortarboard

we all share our nature with the dead

one name carved deep in the cave

of every empty desk is yours

and one name there is mine

.

La superintendente

mirando el aposento confortable

en la casa lujosa

que ella construyó para sí

en el oriente

mi primo dijo

de nuestra tía difunta

posando como viuda aristocrática

reclinada entre sus objetos preciosos

“creía que los misioneros

se suponía que fueran pobres…”

sus almohadas de seda

bordados

dorada tapicerías acolchadas, servicio de

té de plata, finas ropas

jarrones pintados, y

exótico

vestido abotonado hasta arriba

con corpiño

ajustado, los encajes

y cenefas—decana

de clases acaudaladas

maestra de una escuela privada

consejera en

la Sino-Victoriana

de una tierra distante que cambió la mente

como una lenta conversión del verde

en matices sesgados

en los que todo se torna gris

en la triste lamentación de la luz solitaria

envejeciendo

en una patria que ya no es hogar

en el silencio del salón del piano

con ese silencioso tono profundo

de marfil intacto, cada tecla

amarilla como los dientes de un fumador

que no teme

o detesta escuchar

la superintendente de escuelas

con su traqueteo reprobador

y ultra-gramatical,

aclarándose la garganta

con flema “ejem”

desde el fondo del cuarto

su espalda tan tiesa como un puntero

camina a grandes pasos

sus talones golpeteando el suelo

mientras toma la tiza del día

y con un trazo blanco

chirreando

es este un pecado o el sueño de un pecado

ver a través del tercer ojo

como los niños tiemblan

sombreando sus trabajos

por un borrón de errores

los grandes fallos

que sentimos

en la bizquera pedagógica

del extraño de una vez un trimestre

en un aula que huele a tinta derramada

y las notas bajas de la plastilina vieja

fragante en los dedos doblados

y las serpientes de barro multicolores

enrolladas y aplastadas en la tabla de modelar

un nombre gravado profundamente

en la caverna de cada pupitre

porque somos los intimidados, los tímidos

los salvajes, los regordetes

los brillantes, los extraviados

los niños malos, difíciles de complacer

los callados, los espinillosos

los sucios, los pobres

los criminales, los lisiados, los mutilados

los condenados a morir jóvenes

la mala semilla, los que se sorben los mocos, los llorones

fáciles de odiar parloteadores

los consentidos

los golpeados, los atolondrados

los demasiado estúpidos para las palabras

aprendiendo una lección en un sombrero de alta copa

bajo el pelo desgreñado

y uno en el birrete

adornado con borlitas

todos compartimos nuestra naturaleza con los muertos

un nombre gravado hondo en la caverna

de los pupitres vacíos es tuyo

y un nombre allí es mío

.

The Impossible Black Tulip

“The men of old see not the moon

of today; yet the moon of today

is the moon that shone on them.”

……………………—Chinese proverb

I wonder, Ida

when you joined the mission bound for China

did you know the name

Matteo Ricci, the Jesuit priest

from Italy

the man the Chinese still call

“the scholar from the west”

a sixteenth century Catholic polymath

wearing the robes of a Buddhist monk

impressing the mandarins

of the Ming

mastering the culture and

language of the middle kingdom

and then, mapping the world beyond the world

tracing coastlines on the impossible black tulip

of cartography wherever Magellan sailed

and Columbus lost his way

where the Portuguese, the Spanish, the French

the English, the Dutch

went warring for land

and the madness of gold

and the minds

of the savage

and the bodies of slaves

the rivalries of red-haired kings

and red-robed churches

barbarians and buccaneers uncouth humans

in the era of inquisition

after Copernicus spun the globe

and Galileo gave heaven away for fear of burning alive

and there the new lands were named

even the home of your birth Jiānádá

first named and thereby known

by the learned classes

who opened their eyes to the west

and the faith of the west

inscribed with the allegory of the Holy Land

and he, the first westerner

to enter into

the Forbidden City

died a failure to evangelize

though he built a cathedral

in the capital

and still, long after

the gunboats have fallen silent

and the opium wars

have burned away

and the Boxers razed

your home and murdered your kind, and the Japanese

imprisoned you and your children

for the sins of empire—his name

lives on

in reverence—

like Li Po’s drowning moon

held loose

and glowing in the drunkard’s palm

of a midnight pond

the one we might see

if we dare to dream

of a darkness yet to come

.

El tulipán negro imposible

“Los hombres de la antigüedad no ven la luna

de hoy; sin embargo la luna de hoy

es la luna que brilló sobre ellos.”

…………………………………….—Proverbio chino

Me pregunto, Ida

cuando te uniste a la misión destinada a China

si sabías el nombre

Matteo Ricci, el sacerdote jesuita

de Italia

el hombre que los chinos aún llaman

“el sabio del oeste”

un erudito católico del siglo dieciséis

que usaba la túnica de un monje budista

impresionando a los mandarines

de los Ming

que dominaba la cultura y

la lengua del reino medio

y luego, trazaba mapas del mundo más allá del mundo

dibujando la línea de las costas sobre el tulipán negro imposible

de la cartografía dondequiera que navegara Magallanes

y Colón perdiera su ruta

donde los portugueses, los españoles y los franceses

los ingleses, los holandeses

se fueron peleando por tierra

y la locura del oro

por las mentes

de los salvajes

y los cuerpos de los esclavos

las rivalidades de los reyes pelirrojos

y de las iglesias de mantos rojos

bárbaros y bucaneros humanos groseros

en la era de la inquisición

luego de que Copérnico hiciera girar el globo

y Galileo entregara al cielo por temor a que lo quemaran vivo

y entonces se nombraron las nuevas tierras

incluso el hogar de tu nacimiento Jiānádá

primero nombrado y por tanto conocido

por las clases ilustradas

que abrieron sus ojos al oeste

y la fe del oeste

inscrito con la alegoría de la Tierra Santa

y él, el primer occidental

que entrara en

la Ciudad Prohibida

murió en el fracaso de evangelizar

aunque construyó una catedral

en la capital

y aun, mucho más tarde de que

las cañoneras se han callado

y las guerras del opio

han consumido en llamas

y los Bóxer arrasaran

tu hogar y asesinaron a tu gente, y los japoneses

te hicieron prisionera con tus hijos

por los pecados del imperio—su nombre

perdura

en reverencia—

como la luna inundada de Li Po

suelta

y luciendo en la palma del borracho

de una laguna a medianoche

la que veríamos

si nos atrevemos a soñar

en una oscuridad aún por venir

.

Considering Ancient Chinese Erotica

in the spring palace

behind high walls

of the Forbidden City

the perfumed concubine

lolled with her bound-as-a-child body

lamed by beauty

the crimson water lily of the royal house

playing bring on the clouds and the rain

with the wealthy lords

of the Ming

in the court of songs

otherwise dishabille women

their misshapen bones

broken in slippers

crippled by pain her feet made small as a deer

for the visual delight of men

well-born girls

wearing bow shoes embroidered in silk

walking with the lotus gait

the short-step sway of pampered ladies

even in time the eldest daughter of the poor

wanting to marry highborn

achieved the crescent moon

of the cramped arch

with its erotic allure

an intimate and chaste concealment

lasting a thousand years

until the corseted Christians

came at the time of the heavenly foot

their own vital organs cramped

in whalebone

their tight breasts swaddled

in winding-cloth white wear

sending home souvenirs

amazing the congregation

amusing the minister

tantalizing all future museums

where horrified visitors troupe past

in clicking stilettos and blushing tattoos

.

Considerando la antigua erótica china

en el palacio de invierno

detrás de las altas murallas

de la Ciudad Prohibida

la concubina perfumada

se arrellanaba con el cuerpo envuelto como el de un bebé

lisiada por la belleza

el agua de lilas carmesí de la casa real

jugando a llevar al emperador al éxtasis del placer

con los señores acaudalados

de los Ming

en la corte de las canciones

por otra parte mujeres en traje de casa

sus huesos mal formados

rotos en las sandalias

lisiadas por el dolor en sus pies hechos pequeños como los de un venado

para el deleite visual de los hombres

muchachas bien nacidas

usando zapatos de arco bordados en seda

caminando con el modo del loto

el bamboleo de paso corto de las señoras consentidas

incluso con el tiempo las hijas mayores de los pobres

que querían casarse con los de alta cuna

alcanzaban la luna nueva

del arco agarrotado

con su encanto erótico

un casto disimulo íntimo

que dura mil años

hasta las cristianas encorsetadas

llegaron en la época de los pies celestiales

sus órganos vitales agarrotados

entre barbas de ballena

sus apretados pechos envueltos

en blanca ropa enrollada

enviando a casa suvenires

que sorprendían la congregación

divertían al pastor

tentando a todos los museos futuros

donde los visitantes horrorizados pasaban en grupo

en chasqueantes estiletes y tatuajes ruborizados

.

Into a Land of Strangers

the muddy root

of the lotus, also

desires the sky

………………..*

tropical lotus

blooms in the night

white flesh a white moon dreams

………………..*

black water, blue sky

two minds

consider one light

………………..*

undulating cutwater

darkens beneath

the white of a single cloud

………………..*

the lotus open

in the moon-wane of morning

how young a fading white

………………..*

how might the lotus thirst

in the ever-evaporate black

of a deep pool

………………..*

into a land of strangers

she comes

a stranger to herself

………………..*

in the seed pearl

of her beloved moon

the sand grain of her soul

………………..*

celestial stranger

your secret revealed

to a secret concealed

………………..*

an unpainted lotus

imagines the mind

wet brush dampens dry water

………………..*

here in the seam of true silk

the chrysalis clings

to the force of an unborn wing

.

A tierra extranjera

en la raíz lodosa

del loto, también

desea el cielo

………………..*

loto tropical

florece en la noche

blanca carne que una luna blanca sueña

………………..*

agua negra, cielo azul

dos mentes

consideran una luz

………………..*

ondulante rompeolas

se oscurece bajo

el blancor de una nube solitaria

………………..*

se abren los lotos

en el cuarto menguante de la mañana

qué lozano el blanco mortecino

………………..*

como puede el loto languidecer de sed

en el negro en evaporación

de una laguna profunda

………………..*

a tierra extranjera

ella llega

una extranjera para ella misma

………………..*

en la perla seminal

de su amada luna

el grano de arena de su alma

………………..*

extranjera celestial

tu secreto revelado

a un secreto guardado

………………..*

un loto no pintado

imagina la mente

el pincel mojado humedece el agua seca

………………..*

aquí en la sutura de la verdadera seda

cuelga la crisálida

ante la fuerza de un ala por nacer

—John B. Lee & Manuel de Jesus Velázquez Léon

.

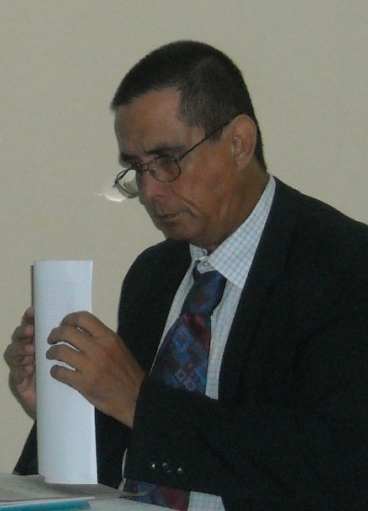

Manuel Leon, translator, and John B. Lee

Manuel Leon, translator, and John B. Lee

John B. Lee is the author of over sixty published books and the recipient of over seventy awards for his writing. Inducted as Poet Laureate of the city of Brantford in perpetuity, he now lives in Port Dover, a fishing town located on the north coast of Lake Erie. He and Manuel have collaborated on translations on several occasions, the most substantial project being Sweet Cuba: The Building of a Poetic Tradition: 1608-1958 (Hidden Brook Press, 2010), a bilingual anthology of Cuban poetry in original Spanish with English translations.

Manuel de Jesus Velázquez Léon is a professor at University of Hoguin. A co-founder of the Canada Cuba Literary Alliance, he is editor-in-chief of the bilingual literary journal, The Ambassador. He and John B. Lee collaborated on the 360-page bilingual anthology Sweet Cuba: The Building of a Poetic Tradition: 1608-1958, (Hidden Brook Press, 2010). Sweet Cuba has been called “the most significant book of translated Cuban poetry ever published.” He lives in Holguin, Cuba, with his wife and their young son and is the publisher of Sand Crab books which recently printed a bilingual editon of Saskatchewan Poet Laureate Glen Sorestad’s book, A Thief of Impeccable Taste.

.

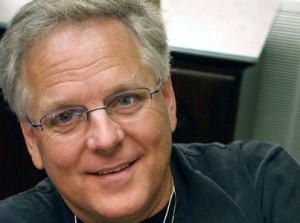

Douglas Glover, photo by Danielle Schaub

Douglas Glover, photo by Danielle Schaub Sydney Lea

Sydney Lea John B. Lee

John B. Lee Marty Gervais

Marty Gervais Michael Schatte

Michael Schatte