Diane Lefer’s essay about Northern Ireland now, in the after-glow of the Troubles that began nearly half-a-century ago, is a cunning amalgam of observation, intervention and charming self-deprecation. It reads conventionally enough till you get to the seventh paragraph where she writes: “Before I say more, let me acknowledge that everything you hear from me may be a load of shite.” At which point you suddenly realize that you’re in the hands of a world-traveler, an activist and a person who knows herself and her perspective. By telling the reader not to trust her, she manages to make the reader trust her (and like her) even more. Oh, such a tricky thing the language is.

Diane Lefer is an old friend, a Numéro Cinq stalwart (a member of what I call the unofficial masthead). She has written a series of essays for NC on subjects varying from abandoned nuclear sites in Los Angeles, to half-way houses for convicts to folk festivals in Colombia. And now she’s been to Northern Ireland. See also Diane’s essay about the Ballymurphy massacre families, “Hunger for Justice,” in the current issue of New Madrid, their special issue on The Great Hunger.

dg

If you fly to Dublin on Aer Lingus, you’ll see that Belfast, Northern Ireland—my destination—is listed as a city in Ireland, not in the UK. Taking the bus north, I must have blinked and missed the border altogether. There’s no checkpoint, no control. Quite a change from The Troubles that erupted in the North in the late 1960’s: 30 years of bombings and shootings. Loyalist paramilitaries killed Catholics, IRA splinter group volunteers killed Protestants and killed police of the Royal Ulster Constabulary and killed British soldiers who did their own share of torture and killing. Ordinary people were caught in the crossfire.

These days, the first time you realize you’re in another country is when you need pounds sterling instead of euros (though if you change your dollars at a branch of the Bank of Ireland, you’ll get perfectly legal pound sterling notes that don’t bear the image of the Queen.)

I went to Northern Ireland in October 2013 to join my frequent collaborator, Hector Aristizábal, and his nonprofit organization, ImaginAction, dedicated to the idea that accessing our imaginations and envisioning alternatives can lead to transformative social change.

Hector grew up in Medellín, Colombia, when it was the most dangerous city in the world. “Theater saved my life,” he says. While his friends in the barrio were recruited by the guerrilla movement, right-wing death squads, or the drug cartels, Hector found his gifts and a wider world through art. After arrest and torture by the military—but also after extensive training and practice both as a theater artist and a psychologist–he ended up in exile in Los Angeles where we met.

Just as psychotherapy aims to heal individual trauma, Hector believes that theater—a form of ritual—can offer communal healing. “Without healing not much social justice is possible.”

The past few years, Hector has offered theater workshops in Belfast and Derry to support peace building by bringing Catholics and Protestants together in joint creative projects. This time I wanted to be there.

Before I say more, let me acknowledge that everything you hear from me may be a load of shite. How does someone enter someone else’s world and in three weeks have the nerve to think she knows it all? Especially when that someone only recently offered a benign picture of life in South LA, including the ice cream truck that made the rounds through the neighborhood. Two weeks after that piece appeared right here in NC, I attended a community meeting where people complained about the ice cream truck that makes the rounds to sell drugs and guns.

This same someone once tried to say Thank you in the Zapotec language to the people who’d welcomed her to their village. Everyone laughed. My bad pronunciation, they said, resulted in my saying Monkey’s bellybutton. It was only years later, visiting again, that a friend said they hadn’t known me well enough in those days to be honest. It wasn’t a bellybutton, it was a penis.

So now that you know I can’t be trusted, let me tell you about Northern Ireland.

I’m glad you’re reading this online. Too many trees have already died for the many hundreds of thousands of pages that tell how ever since the 12th century the Irish have tried to drive the English conqueror from their island. In modern times we eventually ended up where we are now: with the south as the Republic of Ireland and the six northern counties still part of the UK.

If you want a full history, please look it up. Instead, I’ll try to give a brief oversimplified account of what made the North different.

Irish chieftains in the North offered the most resistance to English rule and enlisted military assistance from Catholic Spain. To pacify the region–and we’re talking a long time ago, a century before the Pilgrims landed at Plymouth Rock (or wherever they actually made land)–England created the Plantation of Ulster. Land was confiscated from the indigenous Irish Catholics; Protestants from Scotland and England were settled there, trusted to be loyal to the Crown. The first plan was to get rid of the Irish altogether, but someone was needed to work the farms. Catholics were consigned to inferior status not only socially but by law.

Flash forward to The Troubles.

At last the paramilitaries began to demobilize. With the Good Friday Agreement of 1998, the governments of Britain and Ireland along with the main armed groups agreed on basic principles that guaranteed Catholics in the North equal access to education, housing, employment, and the vote, along with a share of political power. For people around the world, including me, the 1998 accords represented what was possible. Northern Ireland was the model: in spite of hundreds of years of hatred, distrust, and violence, two peoples could say enough, and live in peace.

In Belfast I join up with several other artist/activists who use theater arts to empower vulnerable communities. They are young and eager to learn from Hector and to experience work in a post-conflict society. Anna was born in Poland and raised in The Netherlands which is also home to Evanne who has worked in post-conflict Uganda. Tania was born in El Salvador, raised in Australia. Tamar is from New York but has lived most recently in Germany and Tunisia. Jeroen is an activist from Belgium who knows more about radical politics in the US than I do. The Europeans are all fluent in English though all of us struggle to understand the Northern Irish accent.

So this essay isn’t really about Northern Ireland. It’s about a group of people landing in someone else’s country imagining they have something to offer.

Hector thinks when you are working in your own city or country, you tend to believe you know all about the community. In fact–and I’m living proof–you may be quite ignorant. “People are the experts about their own lives,” he reminds us. In a foreign context, we are less likely to think we know best. Aware of our own ignorance, he says we’re more likely to remain humble and see the workshop participants in an authentic way. Ideally, this will carry over into our work when we return home.

We share a house, shopping, cleaning, and cooking–the latter turning out to be less of a challenge than expected considering our group includes a few omnivores, a couple of mostly-vegetarians, one dedicated vegetarian, and one raw foods vegan. The group dynamic affords Hector a chance to use the skills he developed over decades as a psychotherapist though, personally, I find nothing smooths over tension like the shared viewing of online cat videos.

For me the work starts right away when I meet with the Ballymurphy Massacre Families. Their loved ones were gunned down by British paratroopers in 1971, the killings justified with false claims that the dead were all IRA terrorist gunmen. Forty-two years later, the families are still seeking an official government apology. They want to see the names of their parents and brothers cleared.

There’s already been a documentary about the killings and a stage reenactment but additional ImaginAction artists, led by Alessia Cartoni from Spain, have been helping the families create something different: a play they will perform themselves focused on how they, as surviving family members, were affected. Their stories of trauma and grief should resonate on both sides of the sectarian divide. By evoking shared pain, maybe it’s possible to bolster the shared desire for peace.

Instantly I conclude this is the reality of Northern Ireland today, a place conversant with the language of human rights and the demand that there be no more culture of impunity. It’s not just the Ballymurphy families. Adults who were abused as children in Catholic orphanages and state institutions demonstrate in front of Stormont, the Parliament building, demanding an investigation. People are filing claims for compensation for their torture years ago by the British.

Soon after, though, I conclude that while people are more than willing to air grievances from the past, they won’t face up to problems in the present day.

Then, as the weeks go by, I meet people who don’t want to bring up past grievances at all. Pain is still there, but they want to put it all behind them. “Some people are just obsessed,” I hear. Or, “What do you expect from the lower class?”

People tell me it’s not the same for the younger generation. There’s a frenetic club scene, Protestants and Catholics seeking release, outrunning and out-dancing the past together, fueled by alcohol and ecstasy. But a municipal employee at work in a Protestant neighborhood lowers his voice when he says, “I’m from the other community.” And when I ask a mixed group of university students whether sectarian division is a thing of the past, I get a resounding No.

We have time off for sightseeing. Evanne catches me with her camera as I hike the Red Trail at Giant’s Causeway. Tourists wander over the flat stones that were laid down, according to legend, by Finn MacCool so he could cross the North Channel to Scotland without wetting his giant feet.

The next day we tour the two famous working class neighborhoods in Belfast: the Falls Road (Catholic) and the Shankill (Protestant). Belfast now has a tourist trade which seems to be based on being the birthplace of the Titanic–a ship that went down; Milltown cemetery where you can lay flowers on the grave of IRA hunger-strike martyr Bobby Sands; and the sectarian murals that serve as constant visual provocations.

Yes, there are also murals with messages about safe driving and climate change and nonviolent action but for the most part, they honor the martyrs and promise that resistance (on both sides) will continue. “Peace walls” keep Catholics and Protestants apart and allow foreign visitors to scrawl Kumbaya sentiments on whatever blank space can be found. At night, steel doors close off the road between The Shankill Road and The Falls.

So much for peace. Of course, as I–and everyone–should know by now, governments and leaders can make all the agreements they want, but real change has to start at the grassroots.

And I shouldn’t be surprised that Loyalist extremists reject any political settlement as a sellout and betrayal. They rioted in 2013 when Belfast City Hall began to fly the Union Jack only on state occasions instead of every day. The IRA still murders—“executes”—prison guards. “Just the screws that abuse us,” a prisoner tells me, but I also hear any guard can be killed if his home address becomes known. Splinter groups continue the armed struggle. Teens and adolescents still enjoy recreational rioting–throwing rocks and bricks over the walls at each other’s communities. Loyalists swear they’ll never surrender their allegiance to Britain. Nonviolent Republicans believe it’s only a matter of time till Ireland is united.

Even away from the working class neighborhoods where the conflict has long been centered, we see curbs painted red, white, and blue in the colors of the Union Jack, high rises where the Irish flag flies, portraits of the martyrs, plaques on buildings everywhere memorializing the dead.

I wonder if the backdrop has become so normalized that no one who lives here even notices the hostile defiance. But I don’t believe that. We return to our house and I feel weighed down with a heaviness I can’t shake.

All of us who’ve been involved in community work have been told at one time or another not to get emotionally involved, it’s a surefire path to burnout. But Hector says you have to bring your heart to the work The real cause of burnout, he says, is repressing emotion, being unwilling to acknowledge and face what we feel.

I feel fear. I’m not afraid to be in Belfast. The continued violence from extremists and the dispossessed terrifies me because of what it suggests about the US. Don’t these things ever end? I was never so naive as to imagine racism and bigotry were gone from America where we like to imagine that our history–genocide and slavery–no longer count. That can piss me off, but the virulence of the race hate evident since Obama’s election goes further. It shakes me to the core.

Obama disappoints me but sometimes I suspect he’s overcautious because he, too, is afraid. Not just for himself, though rightwing groups have indeed issued their fatwas, making him a legitimate target for assassination. Does he tread so carefully because of a well founded fear of armed insurrection? If you bother to look, you’ll find the threats out in the open, from the most extreme “patriot” websites to Sarah Palin’s Facebook page.

I think I’ll shake off my depression once we get to work. I can’t wait to meet Protestant extremists–the more extreme, the better. I’ll allow myself to get involved. I’ll connect. I figure I can feel for them without having to agree with them. No Surrender, they say, but as far as I can see, they’ve already lost if their cause was to preserve the status quo. The police force is now integrated with Catholic officers and can no longer be a purely sectarian arm of repression. Catholics have a share in–at times dominate–the government. Loyalists must be scared wondering how they’d fare in a united Ireland.

I can see how the loss of privilege would feel–no matter how irrational the feeling–like violent dispossession. I see that at the same time that Catholics were gaining equal rights, Belfast companies and factories were closing and moving overseas. Working class neighborhoods where good manufacturing jobs were once reserved for Protestants now face massive long term unemployment. These days, to generalize, Catholics blame globalization and capitalism for job loss; Protestants blame the Catholics. And I tell myself if I can empathize with Loyalist extremists and treat them with respect, maybe I’ll do better at recognizing the humanity of angry white men back home.

But it turns out we won’t be working on sectarian reconciliation after all.

We’ve been asked to work with other groups: The Playhouse in Derry is connecting us to low-income youth (vulnerable to recruitment by the paramilitaries), and the LGBT community. The Prison Arts Foundation has invited us to offer workshops in correctional facilities.

Hector’s workshops draw on the techniques of Theater of the Oppressed, developed by Augusto Boal, the late Brazilian theater artist and activist. In fact, Hector and I met more than a decade ago when people in Los Angeles interested in Boal’s methods got together to share techniques. For several years we brought the master himself to town to teach us about using theater arts with vulnerable communities.

Like most Boalians, Hector starts his workshops with games to provoke laughter and loosen inhibitions. Games create a sense of community and also demand focus and concentration. Where Hector is different from most facilitators is that he pushes the group to play at lightning speed. When you move fast enough, there’s no time to feel self-conscious. Everyone is bound to make mistakes and each mistake is celebrated. He wants to get participants past the fear of being wrong.

In Los Angeles, we’ve worked and played with torture survivors who needed the chance to experience their voices as something other than what got them in trouble, their bodies as something other than a site of pain. We’ve played with gang members who needed a chance to be children again (or for the first time). We’ve worked–not as much as we would have liked–with prisoners. In California, it’s very difficult to get permission to bring an arts program into correctional facilities. In Northern Ireland, this turns out to be relatively simple.

It’s not the only difference. I meet a man in maximum security whose baby was born while he was behind bars. He was given a 6-hour leave to go home and hold his son before being returned to custody. I can’t even imagine that happening in California. (At the same time I can’t forget that during the Troubles, torture of prisoners was standard procedure in Northern Ireland.) Inmates in California who want to take college courses have to come up with their own tuition money. In the UK, a free university education is available to at least some prisoners.

We, however, have been asked to work in Hydebank Wood Youth Prison with young men, ages 17-24, who’ve refused to participate in any educational or therapeutic programs. They are, however, intrigued by Hector who comes from the land of cocaine. So they show up, sort of. They squirm in their seats, get up and walk around, don’t make eye contact, talk among themselves, ask for smoking breaks and tea breaks (or take these breaks without asking), turn their heads aside and laugh heh heh heh from the sides of their mouths, and even when they do speak, most of us can’t understand their accents.

Back at the house, we’re discouraged by the lack of participation.

“Then you have a narrow idea of what participation looks like,” Hector tells us. “They are always participating, even when rolling cigarettes, leaving the room. They are being who they are.” We should be learning about them, taking the temperature of the room, and understanding they have no reason to open themselves up to a bunch of strangers who suddenly show up in their lives.

I think I’ve experienced this before faced with a student who seems entirely unresponsive, with whom I am completely unable to connect. Until I realize she or he is paying very close attention–to me. Studying me, figuring out if I’m someone who can be trusted. I have to go on the assumption that this is exactly what’s happening. Stay calm, stay present, remain engaged as if there is a connection.

“We are our own worst enemies because we create our own stories of what we should accomplish,” Hector says. “Get out of your own fucking way.”

Eventually some of the young men talk to us about how they can’t see a future. With or without an education, there are no jobs. The only hope is emigration but with their criminal records they believe the necessary visas will be denied them.

I’m seeing an aspect of Hector’s work I never witnessed before: teacher, mentor. Teaching “is not a process of vomiting information or how well I can talk about topics.” He challenges each one of us. What are the voices inside our heads that block us? Where and when does our energy flag? He probes us, looking at what’s going on inside each of us that may affect our work. “Don’t expect to be handed a curriculum with different techniques spelled out step by step,” he warns us. We will live the technique but what we must do is enter the space fully present, aware, our hearts open. “Learning is an act of love, there’s no other way to learn.”

Am I thinking through an ideological lens rather than with my heart?

I feel…what? Naive. Responsible. I dwell on the American propensity to export war, whether it’s ordinary people in New York and Boston funding the IRA, weapons manufacturers and dealers arming drug cartels in Mexico (and anyone else willing to pay), our support for repressive armies in Latin America, our military interventions around the globe, our drones dropping death from the sky. Yes, we mourn our servicemen and women who die and those who are maimed in body and spirit. But what do most of us, safe at home, know about the killing we pay for?

We’re supposed to be here giving people tools to claim agency over their own lives, while I feel…guilty, and helpless.

Hector finds it strange that the IRA martyrology bothers me more than the aggressively violent imagery of the UVF Loyalists. It troubles me that political tours and Republican museum exhibits are available in the Basque language. I’d like to believe it’s just that people whose own Irish language was in danger of dying out believe in preserving another rare tongue. But I can’t help but suspect collaboration between the IRA and the ETA. You can choose the label yourself: freedom fighter or terrorist.

I’m not Irish American by descent and can claim kin only through extended family, but I grew up in New York hearing–and not always understanding–the songs of the Irish struggle for freedom. They’re hanging men and women/For the wearin’ of the green. I took those lyrics to heart. When I started kindergarten–my first venture outside the safety of home–I checked my plaid skirt carefully for any trace of the dangerous color.

The Irish Republican Army freedom fighters were heroes of my childhood. Later, it was second nature to support anti-colonial struggles.

When I packed to go to Northern Ireland, I knew I had to be (or at least appear to be) neutral. I was cautious again, choosing clothing with no hint of green.

Which side are you on? was the unspoken–and sometimes spoken–question I faced over and over again. And I was ready with my carefully prepared answer: “It all turns out to be more complicated than it looks from the other side of the pond.”

The Irish Civil War…The Troubles. When is enough enough?

In Belfast, a woman sighs and says no cause in the world was worth all the suffering.

One of the Ballymurphy family members tells me, “The Protestants from up on the hill were shooting through our windows. The British killed my father. The IRA killed my brother.”

Hector, it’s not just ideology. My heart is indeed in this place, and my heart is troubled.

We get ID cards and escorts when we enter Maghaberry, the maximum security prison. Then it’s pat-downs and multiple checkpoints with biometrics and down hallways and across yards where guards patrol with dogs.

Most prisoners here spend 23 of 24 hours in their cells. Some have revived the old IRA “dirty protest”–refusing to wash or shave and smearing their cells with their own feces. But we are working with prisoners in “Family Matters”–men who are fathers, and drug-free. They have privileges and are able to move about freely in their own part of the prison as long as they maintain good behavior. They participate in programs meant to reduce recidivism by strengthening parental skills and family ties. Our theater workshops are now part of the program.

We invite people to explore difficulties in their lives by creating scenes for each other. Then we invite participants to reflect on what they’ve seen and improvise alternative scenarios. Theater becomes a rehearsal for life. Improvisation shows you can change the script. People who can’t envision any other path than the one they took can begin to explore other choices.

So: We walk into the room where more than twenty men await us. We have to set the tone right from the start and so we circulate, greeting each individual, introducing ourselves by name, smiling, shaking hands. After fast-paced games and a lot of laughter, Hector continues the workshop with another of Boal’s techniques, Image Theater. Me, I always want to fall back on words, but Image Theater is wordless. We are invited to express emotions through our bodies or, in pairs or in groups, we create random images that are open to multiple interpretations. What you see tells a lot about who you are.

With all this talk about expression through the body, and considering we’re in a prison, it’s no surprise that sexual imagery shows up. One man positions himself in front of Hector who is kneeling. No ambiguity here: everyone sees blowjob. Hector laughs it off and goes on to the next exercise. As he tells us later, he’s glad the subject of sex came up right at the start so we could get it out of the way and move on. I’m impressed with the prisoner, astute enough to test the boundaries with Hector and not with one of the young women.

We break up into small groups to create scenes about problems. But everything’s all right, the men say. They have no concerns.

Of course they have reasons for not speaking openly. One man comes right out and says, “The enemy is here.” They may fear retaliation from the guards. Or, as Hector reminds us, “Why should they open up to you? They don’t know you.”

I try to explain to my group, “For the scene to be dramatic, we need a difficulty or a conflict.”

“No complaints.”

“It’s all right.”

“The Israeli-Palestinian conflict,” one man suggests.

Why do you look outside, at somewhere else? I wonder.

Then I have to wonder who I mean by “you.” Back home in Los Angeles County over the course of 30 years, 25,000 lives were lost to street gang violence–more than in Northern Ireland and Israel/Palestine combined. And why was I saying we needed conflict?–an idea that, as a writer, I always resist. Even Hector has needed to seek alternatives. When he was in China, people insisted conflict could not exist in their society. They structured scenes instead around a dilemma. Maybe a question would work.

“Do you worry about your kids?” I ask.

“Naw. Their mother takes good care of them.”

“Is it difficult for them to come for visits?”

“Naw. No problem.”

“Be ready in five minutes,” Hector says.

Under pressure, we start to role-play a family visit. The father is besieged by his children and his wife all wanting his attention at once. He is stressed and miserable and doesn’t know who to turn to first.

“Time’s up.” Hector wants to see each group’s piece. He adds, “Whatever you do is perfect.”

In the scene we present, the father is reluctant to leave his cell. He wants to see his family, but he hangs back. As he walks at last to the visiting room, Tamar shadows him, speaking aloud the words in his head. During the visit, his two kids and his wife all clamor for attention. By the time the guard tells them to leave, he’s exhausted and depressed, feeling inadequate. Now he opens up about his feelings: As long as he’s in prison, he can’t give them what he wants to give and that they need.

None of the scenes that day looks like professional theater but so what? Hector is right: each one is perfect because it provides fertile ground to ask What do you see? Does this really happen? How might it be different?

Another man tells me later that watching these scenes teaches him empathy.

Every time we drive back to the house, the good feeling of human connection dissipates. I feel assailed by the sectarian slogans and the flags. People tell me no one talks about conflict resolution anymore, but rather conflict transformation. It’s not peace, they say. It’s just a lull. This one context–Northern Ireland–tells me a larger story about wounds that don’t heal. Hatred like a virus lies dormant between deadly outbreaks. The violent troubles throughout the world never seem to end.

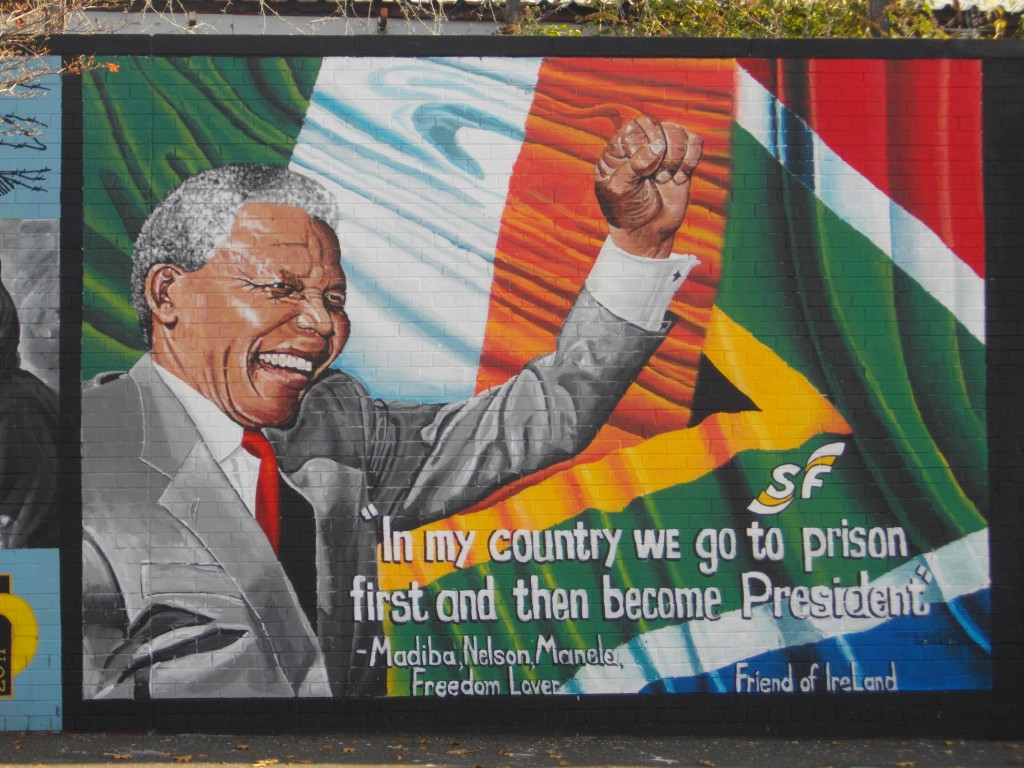

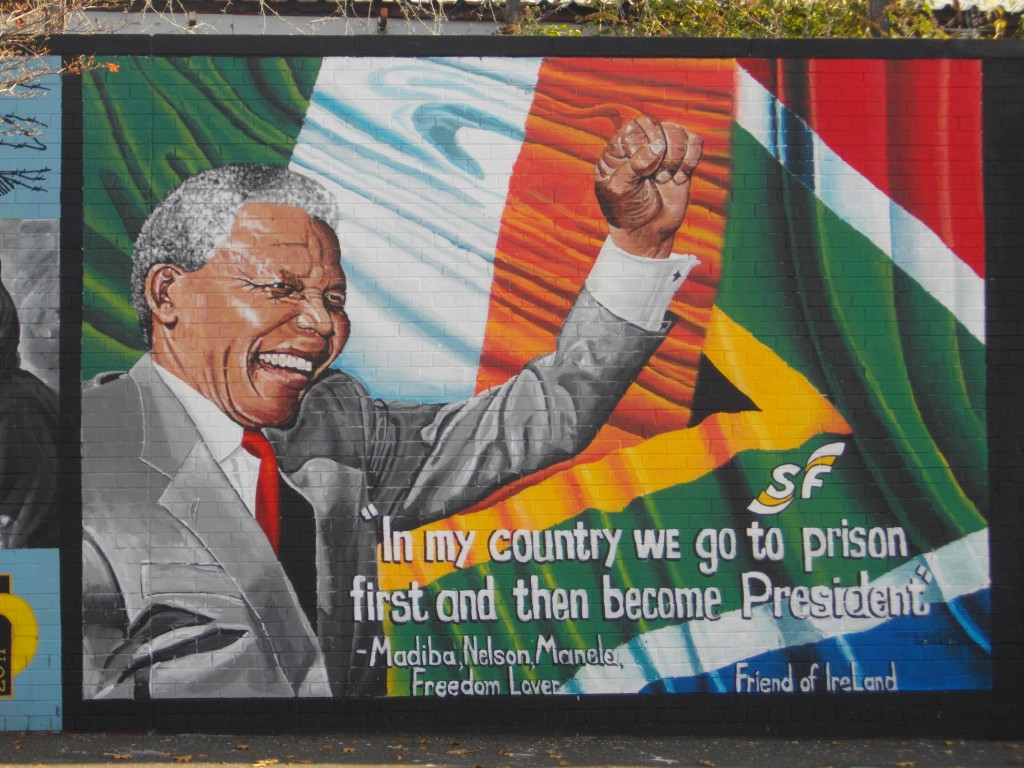

I walk in the park behind our house to clear my head. I remind myself that among the Falls Road murals, there’s a portrait of a Nelson Mandela. He smiles down at everyone who passes, symbol of reconciliation and hope. Inspiring, but the South African story isn’t done. And to use one of Hector’s favorite words, images are “polysemic”–having multiple interpretations. The mural artist included a quote: In my country we go to prison first and then become President.

The writing on the wall: was the artist thinking of forgiveness, or of power?

Before you can forgive, do you have to win?

What a person sees in an image can reveal who she is.

We go to the beautiful city of Derry (also known as Londonderry if you’re a Loyalist or Derry/Londonderry–“Stroke City”–if you’re hedging your bets). The 17th-century city walls stand complete and intact. Catholics, once forbidden to live inside the walls, created the Bogside neighborhood which became the center of the nonviolent civil rights struggle and its own kind of walled city. “Free Derry” lasted from 1969-1972 when residents of the Bogside and Creggan neighborhoods put up barricades to keep the Royal Ulster Constabulary and the British army out.

The armed wing of the IRA was active in Derry too. The famous Bogside murals memorialize the innocent civilians gunned down on Bloody Sunday but also honor the Irish heritage of Che Guevara and the iconic Petrol Bomber of Free Derry, throwing Molotov cocktails at the Brits.

These days, the Derry police station has a security perimeter worthy of a U.S. Embassy and the police do an excellent job of defusing live bombs before they explode.

A Protestant university student tells me, “I’m a Hun.”

“A what?”

“That’s what they call me. A Han. Like in China.”

The Han Chinese were sent to colonize Tibet, to break the back of Tibetan culture and make the region loyal to Beijing.

How long can Protestants in Northern Ireland be considered colonizers and interlopers? I think of Southern California where I live, land that was taken from the Chumash and Tongva and then from Mexico. The descendants of those early inhabitants are still struggling for an equal place.

“I’ll say it about myself,” says the Han. “But don’t call me that.”

[SPACE]

Derry was designated the UK City of Culture for 2013. Dozens of cultural events and celebrations would, in the words of the organizers, provide “a new story for the city to tell to the world.”

In the Neo-baroque Guildhall, Anna and I find an exhibit about the Ulster Plantation and learn some new facts: Scottish settlers were sent over in part to break the power of the Highland chieftains who also resisted English rule. Many were Presbyterians who–Protestant but not Anglican–sought to escape religious persecution. The laws that limited the rights of Catholics in Ulster were applied against Presbyterians too. Anna and I watch a series of panel discussions and debates on video, with actors in period garb offering different perspectives on the Ulster experience. The monologues are carefully scripted so that after each debate when the visitor is asked to push a button to say, for example, whether the sectarian divide is surmountable or insurmountable, almost anyone relying on the video presentation would be likely to choose “surmountable.”

The Bogside artists whose partisan Republican murals draw visitors from around the world were excluded from the City of Culture program.

Mandela also said, “Let bygones be bygones.”

But what if what’s going on hasn’t yet gone by?

Sometimes I think those who remember history are doomed.

I think about that silly book, The End of History, that people unaccountably took so seriously a few decades ago. Fukuyama argued that history had ended with the triumph of Western liberal democracy. I never noticed any such triumph or that humankind had reached a utopian end of the road. But now I begin to wonder if what we’re really seeing is the triumph of the Market. Not the free market, of course, but the rigged market, signaling the End of Society–something Margaret Thatcher famously declared did not exist. With the End of Society, we face the End of Civilization.

Hector takes me to task over my pessimism. If I bring that energy into a group, people will feel it. “Especially when working with young people, it is a huge responsibility to bring medicine. Otherwise you just contribute to hopelessness and apathy.”

And we do work with kids in an afterschool program in an impoverished community–though Hector and I see no homeless people, no burned-out lots filled with trash, no derelict buildings, no graffiti (except on one wall, a phrase people either agree with or fear to paint over: JOIN THE IRA). In spite of decades of Thatcherite austerity, maybe there’s still more of a safety net in the UK. Tania, on the other hand, recognizes signs of deprivation invisible to us. “This is what it looks like in Australia.”

With these kids–a couple of quiet girls, a lot of very jumpy adolescent boys–we start off by playing soccer so they can burn off energy, have some release after hours of sitting in school, and get ready to focus. We also bring them snacks and sandwiches. We have a chance to get to know each other before starting the theater games. And we learn the area is indeed deprived. The kids can’t remember a time when their parents were employed. Families live on government assistance and the adolescents expect they’ll grow up to stay home receiving government checks and playing video games or else they’ll go to jail. There are no jobs.

Their scenes portray teachers blaming kids for offenses they didn’t commit; parents unconcerned when their kids are suspended from school; kids getting into fights and then facing their fathers’ wrath.

The kids are so lively, the love between the older boys and their little brothers so evident, it’s easy to dismiss their realities, the “hopelessness and apathy” that shadow them. I like them so much I want to believe they can step out from under that shadow. I want to believe my pessimism doesn’t show.

Anyway, there’s a difference between rejecting optimism and being a pessimist. Years ago, at the start of the AIDS epidemic when it seemed like everyone who contracted the virus would die and die soon, an activist explained the difference between optimism–blind faith that everything is for the best and will work out just fine– and hope, which keeps you going regardless. He said he’d learned this from Vaclav Havel. Years later, I heard that Havel learned it from B.B. King. Whoever should get credit, I embraced the idea years ago of commitment without any guarantee as to outcome.

The UK no longer recognizes people arrested for sectarian violence as political prisoners. Some political groups have indeed devolved into ordinary thuggish street gangs. (Is that what’s meant by conflict transformation?)

At Maghaberry, some men do consider themselves politicals with the Republicans more outspoken than the Loyalists. One day the men improvise another Visiting Day scene. The young son tells his jailed father he is ready to join the IRA. The father expresses pride.

“What else could the father say?” Hector asks. “Does he really want his son to end up in prison?”

This is how Forum Theater works: people in the audience have the chance to replace a character onstage and try out different words, different behavior. But it seems no one wants to contradict the committed Republican.

I can’t stand it so I volunteer to take the father’s role. “I’m proud of you, my boy,” I say, “for your commitment to our cause. But you don’t want to end up here like me.”

“If it’s where I end up, it’s where I end up.”

“I don’t want that for you.”

But the son is determined to follow in his father’s footsteps.

“All the bloodshed and the time in prison,” I say. “What good has it done? It hasn’t brought us closer to our goal.”

“We have to keep fighting.”

“The fighting hasn’t been effective. It hasn’t gotten us anywhere. There has to be another way.” Idiot American, I think. Keep preaching.

“I’m joining the IRA,” says the son.

“There has to be a better way,” I say. “At least, tell me you’ll think about it.”

I do believe in their cause. But what I’m thinking about is the well intentioned exhibit in the Guildhall. Am I equally guilty of using culture to manipulate?

The father who is playing his son lowers his head and studies the floor. He accommodates me: “I’ll think about it,” he says.

Our last day with the recalcitrant young men at Hydebank Wood, we’re scheduled to present a performance for other prisoners and the staff. We’ve developed and rehearsed a script but our lead actor disappears. The other men don’t want to perform.

Hector actually seems pleased. He’s been trying to teach us that when you work with vulnerable communities, people have very complicated lives. You don’t complain about who’s missing; you work with whoever shows up. You can plan an elaborate production, but you always have to be ready to shift gears. Offer something that engages the audience even if it’s very different from what you planned.

So we foreigners get up and improvise scenes starting with a girl telling her teenage boyfriend she’s pregnant. His response is to walk away.

Hector extends an invitation to the audience. “What else could he say? What else could he do? No, don’t tell me. Come up here and show us.”

All of a sudden we have volunteers. Maybe the guys just want the chance to play at being Evanne’s boyfriend. But one by one, they step up. Telling her to get an abortion. Telling her abortion is wrong. Asking her to marry. Denying it’s his baby. Saying his parents will help. Promising to get a job.

The audience is rapt.

“Now they have the baby. What do you think happens next?”

The baby is crying, the wife is desperate, the unemployed husband comes home drunk and angry. He looks for work. He goes back to selling drugs.

The young men who never sit still, never listen, never “participate” have their attention riveted. They all want to have their say. The prison staff has never seen them like this. One after another they improvise alternatives to the situations they’ve seen in their families, experienced in their own lives, or feared.

“If someone sees you,” says Hector, “it saves your life. You may recognize a gift in a young person who has spent his life misunderstood and stigmatized.” Modest expectations, I think, reaching one person out of many, one at a time. But believing as we do that every human being is of inestimable worth, it should be enough. “By truly seeing him, you give him the experience of seeing himself in a new light, and the strength that comes from this mutual recognition can last a lifetime.”

I’m frustrated by how much people don’t want to see. They are supposed to be the experts in their own lives.

A 12-year-old girl in Derry tells me she can’t wait to get out. Her dream is emigration to Australia. (Australia seems the destination of choice these days. People say they’d love to visit relatives in Boston and New York, but to live in the States? Too violent, too much inequality, not enough opportunity.) She talks about the constant bomb threats, the grenades, and the shootings but assures me, “No, I’m not scared. I’m not nervous. I’m not troubled.” She says everything’s all right, but she can’t wait to leave.

Members of the LGBT group blurt out their concerns: how a lesbian mother has no parental rights and can lose her child if she’s not the biological mother. But when it comes to dramatizing the situation, “No, it’s negative.”

We try a different approach and ask for coming out stories. Of any sort. Tania tells how for years she didn’t want to identify herself publicly as a “refugee.” One man insists he never had to come out because he was always out. Later in the conversation he tells me he was married for years. When his wife learned he was having sex with men, she exposed his secret and he was promptly fired from his job.

I don’t get it. Why all the denial?

One evening a gay man offers a scene in which he goes to donate blood and is turned away. He sits, wordless, head down.

“What is he feeling?” Hector asks.

Sad. Depressed. Humiliated, people suggest.

“What else could he do?” Hector asks.

No one in the LGBT group reacts so members of our group take turns replacing the actor. I ask whether the blood is screened. It is. So there is no medical reason to refuse anyone. I threaten a lawsuit. Jeroen replaces me and, instead of threatening, asks the doctor to sign a letter and petition agreeing there is no medical reason to discriminate. Another member of our team talks about wanting to give blood because a family member was saved by a transfusion. In this scenario, the doctor still can’t change the policy but responds with human empathy instead of putting up a cold bureaucratic wall.

The gay and lesbian members of the group seem to me speechless with surprise. As though it hasn’t occurred to them before that you don’t have to accept things as they are. You don’t have to take it and absorb the hurt. You may not be able to change law or policy right away, but you can assert your humanity. You don’t have to accept discrimination as inevitable and normal.

One day at Maghaberry the prisoners show their scars and merrily reenact the form of street justice called “the six-pack”–as though it’s normal to shoot someone in both knees plus a bullet in each elbow and each ankle. As normal as the murals and the flags. And I think again of the 12-year-old girl. Violence will drive her from her birthplace but at the same time, she won’t admit it bothers her. It’s such an accustomed part of daily life.

It’s her life, their lives. I shouldn’t judge people who are just trying to get by the best they can in a world not my own.

I return home and land at LAX the day before the terminal is invaded by a young man who shoots to kill. A couple of days later, another young man takes his rage to the shopping mall in New Jersey near where my sister lives. The Sandy Hook school site is being demolished. There’s a mass killing in a Detroit barbershop. And another mass shooting and another. I sign a petition or two and go on with my daily life. The 12-year-old girl wants out. I’m not going anywhere. What do I feel? Sad. Depressed. Ashamed.

And I remember the day in Maghaberry Prison when I was paired with a man I could barely understand. He didn’t seem to get what I was saying either. But what with the Irish and Yankee accents, incomprehension had become entirely normal to me. It took two hours till I realized the prisoner was an immigrant from Lithuania with limited English.

Don’t trust me.

— Diane Lefer

Diane Lefer is a playwright, author, and activist whose recent books include a new novel, The Fiery Alphabet, and The Blessing Next to the Wound: A Story of Art, Activism, and Transformation, co-authored with Colombian exile Hector Aristizábal and recommended by Amnesty International as a book to read during Banned Books Week; and the short-story collection, California Transit,awarded the Mary McCarthy Prize. Her NYC-noir, Nobody Wakes Up Pretty, is forthcoming in May from Rainstorm Books and was described by Edgar Award winner Domenic Stansberry as “sifting the ashes of America’s endless class warfare.” Her works for the stage have been produced in LA, NYC, Chicago and points in-between and include Nightwind, also in collaboration with Aristizábal, which has been performed all over the US and the world, including human rights organizations based in Afghanistan and Colombia. Diane has led arts- and games-based writing workshops to boost reading and writing skills and promote social justice in the US and in South America. She is a frequent contributor toCounterPunch, LA Progressive, New Clear Vision, ¡Presente!, and Truthout. Diane’s previous contributions to NC include “What it’s like living here [Los Angeles],” “Writing Instruction as a Social Practice: or What I Did (and Learned) in Barrancabermeja,” a short story “The Tangerine Quandary,” a play God’s Flea and an earlier “Letter from Bolivia: Days and Nights in Cochabamba.”

Out the front window at midnight

Out the front window at midnight Bald eagle in front of the house overlooking the river

Bald eagle in front of the house overlooking the river What the eagles are looking at (usually they would be fishing in the river)

What the eagles are looking at (usually they would be fishing in the river) Lucy, Dog of the North (we’re working on her colour coordination; I told her she couldn’t wear the plaid with the blue boots, but would she listen?)

Lucy, Dog of the North (we’re working on her colour coordination; I told her she couldn’t wear the plaid with the blue boots, but would she listen?)