Charlie Tallulah is on the run, has always been on the run. He left Ireland to escape his family, now he is on the run across the Canadian prairies from a man named Krotz after, um, losing $40,000 (Charlie is possibly not the most dependable of men). The locale of this particular novel segment is woodland near a Cree reserve, the borderlands as it were, where there is precious little law and people live as in a slum except that you can walk out of your hovel and shoot dinner. Charlie has a girl named Cindy and a Gila monster (nameless) when they drop in on his old friend John Lee who lives in a hut and deals guns and homemade whisky.

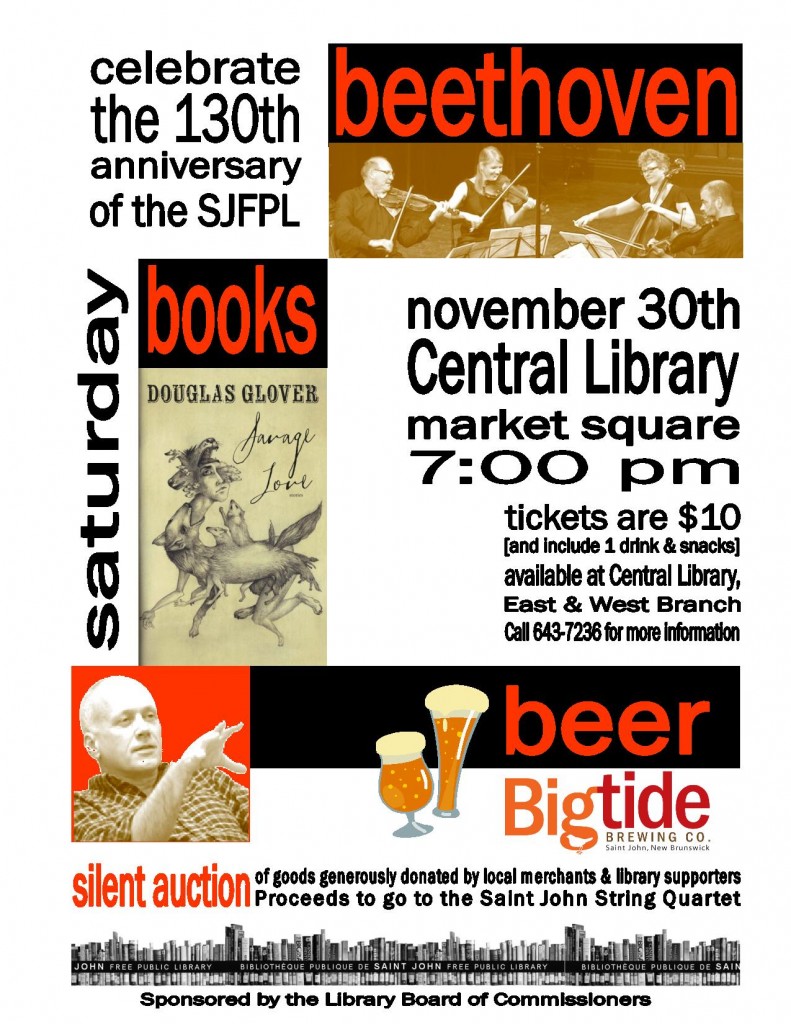

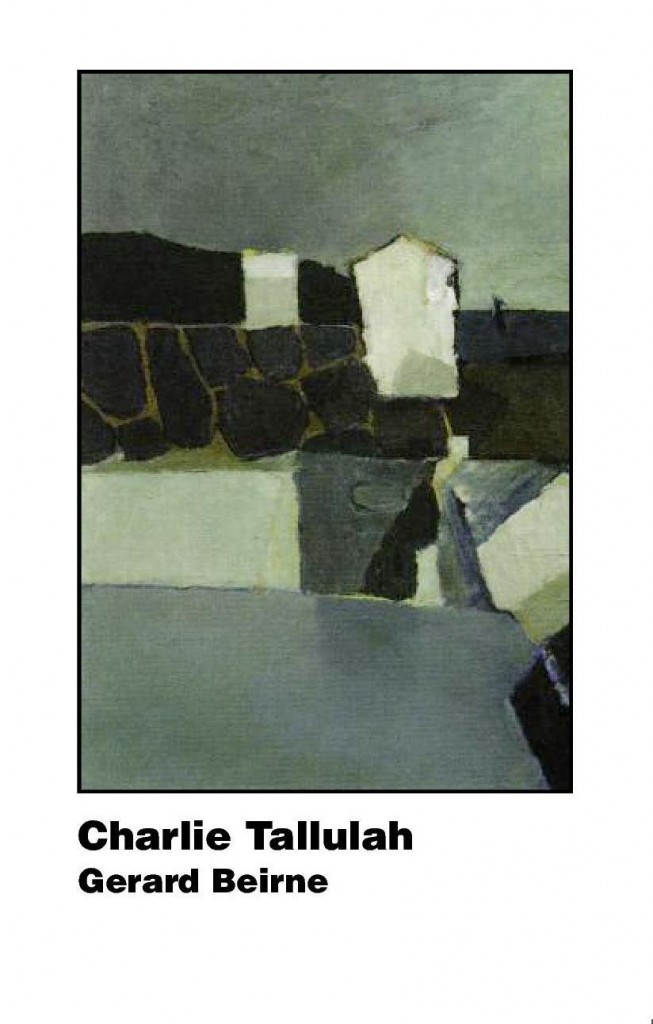

This is from Gerard Beirne‘s new novel Charlie Tallulah, out imminently with Oberon Press in Ottawa. The language is sharp and precise, the dialogue is punctuated à la Joyce using em-dashes instead of quotation marks (see also Robert Day’s serial novel on NC). Two things to note especially: 1) Having lived in the Canadian north by a native reserve for several years, the Irish-born author knows whereof he speaks; and 2) the author’s way of patterning his text with luminous phrases that reach out of their context toward some larger and more mysterious meaning.

He saw her eyes drift towards the open door. John Lee stood there watching them.

-Sorry. I was just passing. But he did not go anywhere.

– What is it you can’t see? Cindy asked.

– A way out, John Lee replied.

And there is a great scene with a girl and a bear skin (as you all know, this is right up my alley).

dg

—

Somehow the stories of Charlie Tallulah’s life never seem to add up, are always less than the sum of their parts, amount to nothing in the end. In this particular story, Charlie is on the run, not only from his past – a previous life and identity in Ireland – but from Krotz who believes Charlie has stolen money from him. Charlie believes otherwise and is surprised when Krotz gives chase – across the Canadian prairies. Charlie meets Lucinda working in a liquor store in Brandon, Manitoba. She too is unhappy with her life and when Krotz shows up, Charlie and Lucinda both take to the road together – in the back of the truck, beneath a tarp, a large glass tank with a Gila Monster Charlie bought, from a store dealing in illegal exotic animals, as a gift for both of them – in the glove compartment, a gun. With nowhere better to go, Charlie follows the back roads to where an old acquaintance of his hides out in a cabin in the woods – John Lee Harper, a gun-runner who had finally stopped running. John Lee now brews illegal alcohol which he sells up North on a ‘dry’ Cree Indian reserve.

—Gerard Beirne

§

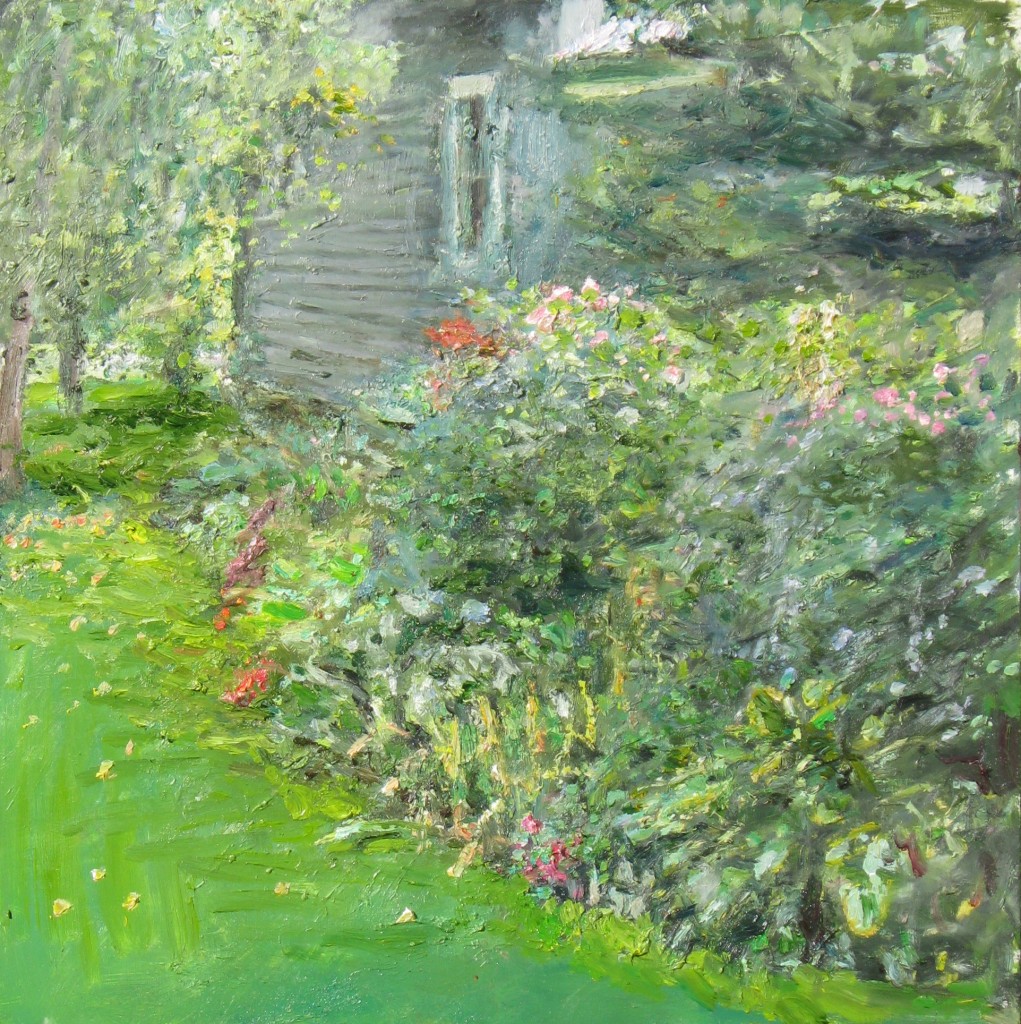

The cabin was set back in the trees, impossible to see from the road. It took five kilometers of dirt to drive there and then a five minute hike in. The structure was small. Three rooms and an outhouse. Water pulled from a well a hundred yards behind. Even at this hour of the morning Charlie and Cindy were sweating from the walk and the sun.

– How do I look? Cindy stopped at the edge of the clearing. Her hair needed washing. Her clothing was stained from dirt and sweat.

– You’re good.

– Well, Charlie, you look like shit.

She carried her soiled jacket in her folded arms. Charlie carried his over his shoulder. He climbed up the steps, opened the screen door and knocked hard on the inner one.

– This place doesn’t look lived in, Cindy said. Are we chasing wild geese?

Charlie knocked again. The thin shredded bark of paper birch lay scattered on the ground. Pine trees and Quaking Aspen. Charlie saw a patch of garden to the side, tall stalks of fresh corn, green potato leaves.

– Somebody’s living here.

He knocked again, called out John Lee’s name. He waited, then heard the sound of something striking wood, the squeak of door hinges. Cindy pulled at her grimy blouse, tucked it into her skirt.

A tall thin man, with a long down-turned moustache and stubble opened the door, looked out at them through the screen.

– Well fuck me!

He wore a red tee-shirt and blue and white striped boxer shorts. He opened the screen door which creaked.

– Charlie-fucking-Tallulah!

He took a double take on seeing Cindy, ran his hand through his swept back greasy hair.

– Can we come in?

John Lee shook his head in mock self-disgust.

– Forgetting my manners, Charlie.

He stood back to let them in. The room was bare except for an armchair, an old pioneers’ pine table and dresser, four mismatched chairs and two propane lanterns on the window sill. Magazines and newspapers were spread at the base of the armchair.

– You’re lucky. I usually greet my guests with Old Bess. He nodded to the shotgun leaning against the wall inside the door. Take a seat. I’m going to make some coffee.

Charlie and Cindy sat at the table. They heard him fill the kettle. He came and stood in the doorway of the kitchen and scratched at the back of his boxer shorts.

– I ought to dress.

– It’s your home, Charlie said.

– I’m not used to ladies here is the thing. Like to say I don’t have much need for them, but that would not be the truth. He pulled at the side of his moustache. As a race we’re a fucking mess. Slaves to our desires, you’ve heard it before. He turned back into the kitchen. My bedroom’s through this way, he said. I will dress for the occasion.

– He’s okay, Charlie reassured her when he was gone.

John Lee came back a few minutes later wearing the same tee shirt, a pair of blue jeans and green socks. His hair was wet where he had thrown water on it. He carried a pot of coffee and three chipped mugs.

– So to what do I owe the pleasure? It is pleasure, isn’t it? He pulled at his moustache again. I don’t do guns anymore.

– I know, Charlie said. I know that.

– Just so’s you know.

– This is Lucinda.

John Lee nodded.

– You must be hungry, he said. I’ll cook you up my special.

Cindy and Charlie watched him cut up sausages, bacon, tomatoes, and potatoes. Then he fried it all up in beaten egg with shredded cheddar and mozzarella cheese, a little salt and pepper.

– Man! Charlie said when they had finished. It was worth travelling all the way for that.

John Lee opened the curtains a little. A shaft of light fell across the table. Their stomachs were full now, it was time to talk.

– All what way?

– Vancouver, Saskatoon, Brandon, I don’t know.

Cindy heard what sounded like children fighting outside. Neither John Lee nor Charlie seemed to notice.

– Sounds like you’re running, John Lee said.

The noise got louder, clearer. Geese. Cindy could see them through the gap in the curtains.

John Lee went over, picked up his shotgun and walked outside. The geese sounded excited all talking at once loud and unstoppable. Then the gunshot and the shocking momentary silence which followed as though even these basic animals were capable of recognizing their mortality and were stunned by it in turn. The silence that ended as suddenly. The scattering and screeching.

Cindy looked at Charlie. He held his mug, gave nothing away. They waited there until John Lee returned carrying a goose by its neck. He placed his shotgun back against the wall, then threw the goose on the table.

– Dinner. He washed his hands in the kitchen, came back in and sat down.

Cindy saw the red stained feathers. Its large limp body. Its dark grey head and neck, its soft white cheek and undertail, its gnarled webbed foot. She couldn’t look it in the eye.

– Who are you running from?

Charlie leaned back on his chair, watched the random motion of the specks of dust trapped in the shaft of light.

– A guy named Krotz, you know him?

John Lee nodded.

– Yeah, I dealt with him in the past.

– Maybe Lyle.

– Lyle? John Lee sounded surprised. Toque Lyle?

– He’s with Krotz now. They both came bursting in on me in Brandon. I was out at the time. Lucinda took the call.

John Lee looked at her with what could be mistaken for concern.

– Did they harm you?

She shook her head.

– I don’t know about Krotz, John Lee said. I don’t really know how far he would take it. I sold him two .375 magnums. What he does with them is anybody’s guess. I don’t want to be the one to find out.

Charlie took in John Lee in his home, this cabin of plywood and metal siding which contained him, his sparse room, bare floor boards, white and green cotton print curtains, stubble, drooping moustache, Old Bess. He didn’t seem happy or unhappy. He had a small garden, a dead goose on his kitchen table. There was a still, moonshine hidden away someplace.

Cindy looked at the two of them. She wondered how far back they really went. She was wedged in between them, stuck somewhere in the middle of Charlie’s life, caught up in her own.

– Do you have soap? The words just came out, almost unintended.

– Do I look unwashed?

– Not you, me, Cindy said. I haven’t had a proper wash in days.

– I have a tub out back. No hot water I’m afraid. But yes I do have soap.

John Lee brought her through the kitchen and out the back door. An old aluminum tub stood on a rectangle of dirt reclaimed from the wild grasses. A black plastic pipe ran from the faucet to a water tank perched on a plinth above it. The plug hole led directly to the ground where a channel covered in gravel drained the dirty water away.

– It’s the best I got to offer. He looked around at the grass and tall trees. Can’t ask for much more privacy than this. I got towels inside.

He brought her some towels and went back inside with Charlie. He knocked on the kitchen window. Cindy looked in at him.

– We’ll be up front. Take all the time you need, John Lee said bending down to open the cupboard beneath the sink. He took out a four litre milk container filled with a clear liquid. What time of day is it? he asked

– Time enough, Charlie said emptying the remains of the coffee from their mugs and washing them under the tap.

John Lee brought the container into the front room and sat down. Charlie put the washed mugs still dripping with water on the table beside him. John Lee filled them half-ways up.

He banged his mug against Charlie’s. Charlie took a sip.

– Jesus H!

John Lee laughed.

– Who buys this stuff? Charlie asked.

John Lee swallowed, savored the taste still fused to his throat.

– There’s a line. This is good, trust me.

– I do.

– 65 proof. That, he said pointing to the four liters, sells for sixty bucks.

– You’re joking.

– I kid you not.

Charlie took another drink and lit a fuse all the way to his stomach.

– It’s the fourth of July!

– I sell most of it to the reserves.

– So that’s your business.

– They’re good customers.

– What about the law, are they onto you?

– They don’t care. It’s like the good old days. Fire water. Keeps the natives distracted while the government shits on them more. Colored beads, that sort of thing.

– Doesn’t it bother you? Isn’t that why you gave up the guns, the unpleasant outcomes?

John Lee fiddled with the cap on the milk container.

– Maybe you’ve got me there, maybe you haven’t. The way I see it this stuff is in their own hands, under their control. Criminals always abuse guns, that I should have known, but people don’t have to abuse this. John Lee stood up, did not seem convinced by his own argument. Now, I could say I need to do something in the kitchen, he admitted, but if you don’t mind I would like to look at my tub. I have never seen it with a woman bathing in it before.

– What if she minds?

John Lee raised his eyebrows.

– Maybe I should go and ask her.

He stood to the side of the kitchen window and looked out. Cindy was stretched in the tub, her eyes closed, her shimmering breasts floating on the top. Beneath the water the sheen of her stomach perhaps, maybe the shadow of her thighs. He would like to have seen her turn over, or for her to stand up and dry herself off. He came back in and sat down, pushed his lips together, twisted the ends of his moustache.

– I ought to feel ashamed, he said, be saddened by my behaviour. He took a drink, wiped his lips. I am unworthy of her, that much I know.

Cindy lay back in John Lee’s tub unaware of his eyes upon her. The grass grew wild around her. The trees quaked in her presence. The cold water lapped at her body. She watched a blue jay fly overhead, perch on the nearby branch of a pine tree. Perhaps this was all it took, a chance encounter. Relationships were fraught with risk. When the fear subsided Cindy was happy to be with Charlie, happy to be on his arm. She closed her eyes, breathed in the fresh air. Her job in Brandon was tedious, her life uninteresting. Charlie was not the answer, but it felt to Cindy as though he was part of the solution. The problem was not so clear. It certainly had something to do with her father’s death and her absence. It was accentuated by this, amplified. But it had not begun there, had been at hand as far back as Cindy could recall. She had always felt absent as though her place in her family eluded her.

Cindy’s sister, Jackie, had phoned her shortly after she had moved out to complain.

– I thought you were supposed to be taking care of Father.

– Where are you? Cindy asked.

– You know I can’t come back. I am already obligated. But you had no reason to leave.

– No reason?

– He’s ill for heaven’s sake. I can’t believe you left our mother to mind him on her own.

– You left me on my own with them.

– You’re being unreasonable, Lucinda. He wasn’t ill at the time. There was no need for me to stay then. But you were needed. What were you thinking of?

My life, she should have replied.

When he died her sister called again to tell her what her own mother would not.

– Daddy died, Jackie simply said. You didn’t even know did you? Well I am here with her now. She says there is no need for you to come.

– Of course I’ll come, Cindy said. I’d have come sooner if I had known. Why didn’t you call me as soon as you heard?

– If you had been here, you would have known.

I’m not the only one at fault here, Cindy wanted to tell her. Yet I’m the one bearing the faults of all.

Throughout the time of the funeral her mother barely looked at her, speaking only when necessary.

– You can go now, she said the day after he had been buried. You have been here long enough.

Cindy returned to Brandon. She talked to her mother a few times on the phone, but her mother made it clear that she did not wish her to call anymore, made it clear she was not welcome anymore in their home.

How little it takes for a life to fall apart. Cindy lay in the tub with her eyes closed and listened to the songs of the birds, the rustle of the tall grasses. Despite all that had occurred she felt strangely at peace now. Such things were possible it seemed.

– So tell me, why is Krotz on your tail?

– He thinks I let him down.

– And did you?

– I don’t know. How do you know when you’ve let someone down?

– They tell you, I guess. In words or other ways.

Charlie put his hands flat on the table and held them there as though he could make it levitate.

– He wanted something I couldn’t give him.

– What was it? John Lee watched Charlie’s hands as though he thought levitation was entirely possible, could happen right before his eyes.

– I could say it was money, but that would not be entirely accurate. Charlie seemed to give up. He took his hands from the table, looked at them forlornly. He wanted a part of me, he said.

– Doesn’t everyone? John Lee looked disappointed as if Charlie had somehow let him down. So how much money?

– Forty thousand.

– That is by no means a small amount.

– It was not my money, Charlie told him. I was merely the delivery boy, but in the end I failed to deliver. Charlie folded his arms in front of him, trapped his hands beneath them.

– How wise was that?

– I know.

– So what did you do with it? You didn’t bring it here did you?

– The thing is, I lost it.

John Lee looked at him in disbelief.

– You lost forty thousand dollars?

– In a manner of speaking.

Cindy came back in the room wrapped in one of John Lee’s towels. They both glanced up at her, distracted now from Charlie’s tale.

– I washed my clothes out, she explained. They’ll soon dry in this heat.

John Lee grinned.

– I’m not complaining.

– I feel much better, thanks. I feel like the dirt of the world has been lifted off me.

– Another illusion, Charlie said.

Cindy made a face at him.

– Don’t be mean spirited.

– Speaking of mean spirit, John Lee said, fetch yourself a mug.

Cindy pulled the towel more tightly around her, twisted it under her arms. She turned around to enter the kitchen, the towel adhering to the line of her buttocks. John Lee glanced at Charlie forlornly.

– It’s early for me, she said, bringing the mug back in.

– It’s early for us all. John Lee unscrewed the cap and poured them a drink.

– Be warned, Charlie told her.

– I hear a voice, John Lee said.

Cindy took a cautious sip.

– Whoh!

John Lee looked at her, smiled. He had seen beneath her towel. Be warned, the voice repeated. Whoh! John Lee answered.

He was happy with them here. He hadn’t had company in quite some time.

– You can stay here as long as you need to, he told them. It’s no Super 8, but hey the liquor’s good.

– Appreciate that, Charlie said. Just until I get a plan, do some logical thinking. We’ve been running blind.

John Lee thought of Cindy’s clothes drying outside, felt oddly pleased.

– You two can take my room. I’ll make up something here on the floor.

– We’re good here, Charlie told him.

– This is the way I’d prefer it, John Lee said. It’d give you more privacy, me more peace of mind.

Charlie remembered Gila.

– There’s something else. Another guest.

John Lee looked uncertain.

– What are you springing on me now?

– Don’t you worry about it. He’s a man after your own heart. Charlie left the two of them there and walked back for Gila.

– So how long have you known Charlie? she asked.

John Lee scratched his head.

– I can’t say I’ve ever known him. We met in Vancouver about six years back. Moved in the same circles. John Lee laughed, showed teeth that were going yellow. We hung out together sometimes. He helped me, I helped him. Mostly we got drunk together. John Lee shrugged with one shoulder. Even then Charlie was not entirely committed. What about you? How long have you known him?

– A few days.

John Lee’s lips drooped like his moustache.

– That figures. So what do you think?

– About what?

– Charlie, you both? I don’t know.

Cindy laughed.

– I don’t know either.

– And Krotz, what did you think of Krotz?

– He scared me. I thought he was going to do me some harm.

– He still could. You running with Charlie and all that.

– I know that. Cindy felt her fear return.

– Just so’s you do.

– I took off with Charlie because of Krotz. He knew where I worked. I was afraid he would come after me if he couldn’t find Charlie.

– It’s not unlikely.

Charlie came back in a short while later with Gila. He put the tank down on the table. John Lee squinted into the tank, screwed his face up in disgust.

– Jesus, Charlie, what is that?

– Gila monster. Sort of like an overgrown lizard.

– Is he safe? He doesn’t look safe.

– You’ve got to be careful. Can’t get too close. He must be starving though. We haven’t fed him more than a couple of mice in days.

– He’ll do alright then. We’ve got plenty of mice around here, rats too. Don’t worry, he told Cindy, they don’t usually come in the house.

John Lee fixed up the room for them, moved his belongings. Cindy was tired, woozy from moonshine. She excused herself to rest up a while. The room was small. Apart from an old double bed there was a chest of drawers with a propane lantern on top, a trunk, and a wooden chair. Traps hung from one wall, a large fish stuffed and mounted on another, and a bear-skin lay on the wooden floor as a rug. The window had the same cotton print curtains as the front room. Cindy pulled them over and stepped out of the towel. She lifted up the bear-skin and wrapped it around her, covering her head with its head. Then she turned the skin around and wrapped in its fur climbed into bed. She was losing track of the days already. She tried to trace them in her mind but soon drifted off to sleep.

John Lee told Charlie he’d bring him out to show him his still. He took his shotgun and walked with Charlie back out onto the dirt road where Charlie had parked. He walked over to the trees and moved some heaped up branches to disclose a hidden track. About fifty yards into the forest John Lee stopped and pulled away more branches to reveal a tarp covered truck.

He winked over at Charlie.

– I’m not at home if I don’t want to be.

He got in and started the engine. We can drive some of the way, but after that we’ve got to hike. They drove through dense forest hacked back to make way for a vehicle. They bounced over tree roots and rutted ground. Low branches scraped against the roof and windows. Sunlight filtered through the treetops. Wood pigeons flew from above. After about fifteen minutes of driving, John Lee abruptly stopped the truck.

– Road’s run out, he said taking his shotgun from the rack. We got to hoof it from here.

A small foot-worn trail led through the trees. John Lee whistled as he went.

– This is bear-country, need to let ‘em know we’re coming.

A grey squirrel ran up the tree-trunk to Charlie’s side. John Lee raised his shotgun, got the squirrel in his sights.

– Boom! He laughed, lowered his gun. Haven’t eaten a squirrel since I was a kid. You ever eaten one?

Charlie shook his head.

– Where’d you grow up anyway? John Lee swung the shotgun over his shoulder.

– I never grew up, Charlie replied.

– I guess not many of us do. You sound like you come from out east.

– Further east than you think.

John Lee lifted up a low lying branch and ducked his head under it.

– Are you telling me you weren’t born here?

– That’s right, said Charlie sidestepping the branch as it swung back at him.

– So where were you born?

– That’s a long time ago.

– Not so long you can’t remember.

– This is between you and me.

– Right.

Charlie saw a yellow and black ladybug land on his shoulder. He placed his finger in its path so that it walked on it. He held it out in front of him examined the frail shell of his spotted wings.

– Ireland.

– Ireland!

Charlie flicked the ladybug off his finger, saw it fall then fly to safety onto a branch. Charlie had never told anyone this before. He was on the run from his past. If he hadn’t been laden with John Lee’s moonshine, he most probably would not have told him either. If he hadn’t been running from Krotz. He regretted it immediately.

– Listen John Lee, I don’t want to talk about this.

– Well fuck me, Charlie, there’s a lot of things we don’t want to talk about. I mean I don’t want to talk about this moonshine, and yet here we are. They stepped into a small man-made clearing. John Lee pointed with his shotgun to a small wooden shed.

– Welcome to my world.

Charlie heard the whir of a pump. John Lee opened the lock and pushed the door inwards. A large steel barrel stood in the middle of the floor with a long copper pipe extending upwards from it. Clear plastic tubing attached to the pipe connected into a cylinder and out the bottom into another barrel. Eight ten-gallon oil drums were stacked to one side and a row of plastic containers on the other.

– Bush whiskey, John Lee said.

– How does it work? Charlie asked.

– A little bit of chemistry, nothing more. He pointed to the containers. That’s where I make my mash from. Cornmeal, sugar, yeast, malt, water. You just mix it and let it ferment in the boiler. He kicked at the base of the stainless steel barrel. You heat it up until the mash vaporizes and then condense it. I just keep it pumping around. Fractional distillation if you remember anything from your school days. Separates the different substances. The water boils off at 100 degrees. The stuff you and I want is Ethyl-Alcohol. That separates out at 78.8 degrees. After that it’s Methyl-Alcohol, turns your brains to jello. That stuff I keep for fuelling my truck.

John Lee started the boiler up. Charlie watched as he fiddled with the faucet and thermostats adjusting the flow until a clear liquid trickled into the barrel. John Lee poured them off a sample in two tin cups. They brought them outside and sat down with their backs against the shed.

– A fucking Irishman! John Lee grinned over the top of his tin cup.

Charlie looked up at the sky through the gap in the trees. A large black mushroom cap cloud had blown in. Cream colored light played at its lower edges.

John Lee took a drink, tasted its rawness on his throat. So why did you leave?

– I needed a break.

– How long ago?

– Fifteen or so years.

– That’s a long break, Charlie. You ever been back?

Charlie shook his head.

– But you still got family there, right?

– I don’t know.

– You don’t know?

– I never got around to telling anyone I was leaving. Charlie stared into his cup, leaned back against the shed. I needed to start over, he said. Take another shot at it. Turn into the person I wanted to be, not the one everyone else thought I should be.

John Lee nodded in agreement.

– I had a family who drove me to distraction too. A father who drank himself to death and a mother who followed him soon after just so’s she could watch him rot in hell. A sister who disapproves of my lifestyle, and well who can blame her? I do of course, so we hardly ever see one another. It’s possible for years to go by.

Charlie looked around at John Lee’s hiding spot. Another alternative. To clear a path into the heart of the wilds, cover your tracks, stay put.

– Who else knows about this place?

– It’s not a place I bring people to. This is my own illicit part of the universe.

– You’ve got it made.

– You know, Charlie, I believe I really do. He drained the rest of his cup. I’ve got a run to do tomorrow. You want to come with me, bring Lucinda too? There’s a reserve I got to deliver to. We just head north ‘til the road disappears. It’s gravel after that. It’ll take a good four hours to get there. I know a lady there. I sometimes stay a day or two then head back down.

– So there is a lady in your life?

– I wouldn’t put it like that. I see her on occasions. That hardly constitutes my life. So what do you say, Charlie, d’you want to come?

– I would like to go, he said. I believe I really would.

Charlie looked in on Cindy when they returned. He saw her tucked beneath the blankets. He went over and climbed in beside her. As soon as he did she shucked the blankets off them and leapt upon him covered in the bear-skin, growling hungrily.

Charlie wrestled her down on the bed, rubbed her furry rump. She dug the bear claws into his chest, tore at him. He pushed hard and turned her over on the mattress. The bear-skin fell free of her naked body. Cindy’s arms were raised in the air holding Charlie’s strong wrists.

He saw her eyes drift towards the open door. John Lee stood there watching them.

-Sorry. I was just passing. But he did not go anywhere.

– What is it you can’t see? Cindy asked.

– A way out, John Lee replied.

/

Cindy said, why not, when asked about the trip north.

– You mean it? Charlie asked still recovering from their lovemaking. In the midst of her passion she had bitten him hard on the leg. Charlie screamed with the pain, almost kicked her in the face as he freed his leg from her bite.

– Have I complained this far?

– I just wanted to be sure.

– Well don’t count on that. I’m not sure about anything.

– You’re in good company, Charlie told her. He squeezed her bare shoulder, saw the flush of their passion on her neck and upper chest. He heard the geese again outside. The continual migration.

– What’s up with John Lee?

– Lonely, I guess.

– Aren’t we all, but we don’t go peeping in at other people.

Charlie looked up at the stuffed walleye. It stared back uneasily at him. A different fish entirely than the one John Lee had caught. Its innards removed, its painted skin, its false eyes which stared down at them. Trophy. The traps on the walls looked ready to spring.

Charlie and Cindy arose later that evening. The smell of goose cooking drifted in from the kitchen. John Lee had scalded the goose in boiling water, plucked it on the table. He fed Gila now the gizzard, heart and liver.

– So you guys finally got done. Come and join me.

– We were almost going to say that to you, Cindy said.

John Lee looked embarrassed, wiped his hands on his jeans.

– I’m not used to company.

The black clouds continued to blow in from the east. Thick rolled-over swathes of darkness folded towards the earth. Flat harvested fields, broken-down homesteads, lone trees, ancient machinery. The tireless steel wheels of early tractors, the rotted remains of fencing, loops of unattached wire, giant cylinders of pale nicotine fingered hay, torn strips of clear sky. The humid air was laden with heat, tension.

– It’ll break soon, John Lee said.

As he spoke the trees began to sway, and the forewarning winds swept through. A metal bucket rolled across the yard. A door slammed repeatedly on its hinges. A yellow fork of lightning flashed in the distant sky. Cindy waited for the sound of thunder which never came. The sound of rain, maybe hail, on the roof. Beating against her bedroom window. Huddled into her sister for comfort. Another flash.

– The last storm started a fire a few miles west, John Lee said. Lightning hit a tree. It was so dry the whole thing went up. They had to fly water bombers in, dropping thousands of gallons on top of it, took a couple of days before they got it under control. If the winds had changed, I’d have been out of here for good.

The door rattled and the flaps on the air vents outside smacked down. Gila looked uneasy, his eyes flicked back and forth.

– Had a dog once that would have spent the day howling, John Lee went on. When it finally came he would run and hide beneath the table. There are things those animals can intuit we cannot. A portion of our senses we have forsaken for consciousness. It’s a raw deal when you think about it. Just watch two dogs humping. Going at it as if nothing else mattered, then moments later not giving a fuck about that either.

He spoke now to Cindy as though to explain something to her that would make her feel better about his life.

-That’s why I am alone out here. I’m trying to regain my senses.

A purple sheet of lightning flashed through the window. Cindy felt the flesh of one thigh touching the other uncomfortably. She crossed and uncrossed her legs. A rumble of thunder, ongoing like simmering anger. Charlie remembered the gun in the glove compartment. Telling John Lee where he had come from had unsettled him. For the first time since he had left, he began to doubt if there was any such thing as a clean break.

Another flash and a louder roar. The world a little edgy. These were the moments of bar room brawls, unprovoked attacks, inexplicable violence. John Lee tapped his feet on the wooden floorboards. Cindy shifted in her seat. Her recently washed clothing already damp with sweat. Charlie’s face unshaven.

John Lee challenged him to an arm wrestle. Cindy watched their gritted teeth, the hard lines of their tensed jaws, the clenched whitened hands, the thick veins of their forearms, the bulge of upper-arm muscle. She recalled the innards John Lee had torn from the plucked goose, how he had dropped them into Gila’s tank, slimy and red raw. Gila devouring them as John Lee devoured Charlie’s strength and resolve, slamming his arm to the table, the bones of his hand cracking down on the wood.

John Lee grunted, let go Charlie’s hand with no expression of pleasure in his friend’s defeat.

– The goose, was all he said and stood up to go to the kitchen.

Charlie looked at his hand and arm as though they were detached from him, and then across to Cindy as if to ascertain that she was not likewise removed.

– You put up a good fight, she said.

Charlie lifted his arm from the table, clenched and unclenched his fingers.

– You cannot depend on me, remember that.

Cindy walked over to the window. The dark cracked open into light. The loud retorts. Charlie looked at Old Bess lying against the wall beside her. Loaded, ready for action. John Lee came back in with the cooked goose on a large wooden breadboard. He laid it in the center of the table. Cindy sat back down. And as lightning flashed around them and thunder roared, they tore pieces off the goose’s plump body with their sweaty fingers and greedily ate the greasy flesh.

—Gerard Beirne

—————————–

Gerard Beirne is an Irish author who moved to Canada in 1999. He is a past recipient of The Sunday Tribune/Hennessy New Irish Writer of the Year award. He was appointed Writer-in-Residence at the University of New Brunswick 2008-2009 and continues to live in Fredericton where he is a Fiction Editor with The Fiddlehead. He has published two previous novels including The Eskimo in the Net (Marion Boyars Publishers, London, 2003) which was shortlisted for the Kerry Group Irish Fiction Award 2004 for the best book of Irish fiction and was selected as Book of the Year 2004 by The Daily Express (England). His poetry collections include Digging My Own Grave (Dedalus Press) which was runner-up in The Patrick Kavanagh Award.