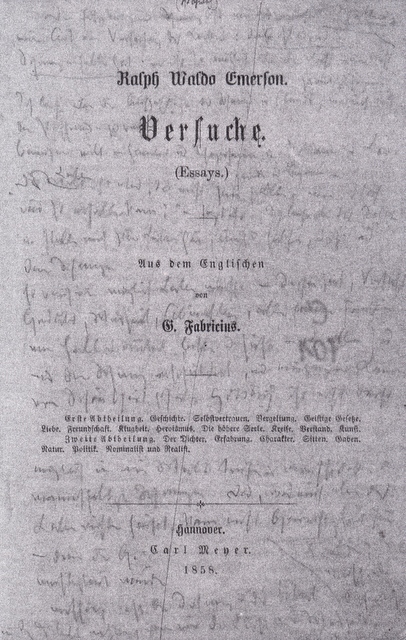

In an eloquent, erudite and brilliant essay, Patrick J. Keane takes us straight into the heart of Nietzsche’s concept of perspectivism, his somewhat or so-called relativist riposte to Enlightenment rationalism and the God-backed objectivism of Descartes, which sounds daunting except that Pat is so damn entertaining and will insist on packing his essays with spectacular quotations, asides, and digressions so that you just want to stop and dwell. I stopped and thought when I got to the Nietzsche quotes on truth as a woman (and Pat’s excursus on feminism) and then the Nietzsche quotes on interpretation and text (yes, yes, while all fiction writers may have crawled out from under Gogol’s overcoat, all modern philosophy, literary criticism and politics seem to have crawled out from under Nietzsche). I also especially liked the asides on Emerson’s influence on Nietzsche (we have an image of Nietzsche’s copy of Emerson’s essays, scribbled over with notes) and Pat’s amazing appendix on The Tempest and (yes) his melancholy reference to Nietzsche’s sad last years (and we have sketches, photos and even film/video of Nietzsche a year before he died). I could go on but will stop. Read the essay.

dg

§

This essay on Nietzsche’s legacy has nothing to do with that passé topic, “Nietzsche and the Nazis,” nor, other than peripherally, with his central concepts of the Űbermensch or Eternal Recurrence, nor the contrast between the Apollonian and the Dionysian. Even the Will to Power, his thoughts on Slave Morality and Master Morality, and Nietzsche’s assault on Christianity are here subsumed within a wider challenge: to the transcendence of God and to all scientific, philosophic, and moral claims to universality. In exploring his undermining of the Absolute, especially of the traditional philosophic and religious belief that truth is One and unchanging, I will focus on Nietzsche’s radical perspectivism, its relation to earlier “modern philosophy,” and, especially, its role in contemporary thought and “theory.” Though the poststructuralist floodtide may have receded somewhat, the diffused impact remains, and Nietzsche continues to be, in the phrase of Simon Blackburn, “the most influential of the great philosophers and the ‘patron saint of postmodernism’,” his thought—according to Jurgen Habermas, in The Philosophical Discourse of Modernity—“the entry into post-modernity.” But my main point is that the patron and precursor adopted and adapted by postmodern theorists is not the only “Nietzsche.” After discussing René Descartes and the ambiguous legacy he bequeathed to subsequent thinkers, I’ll turn to Nietzsche’s even more ambiguous legacy. Navigating a course between the extremes of Cartesian objectivism and the utter relativism all-too-often associated with Nietzsche, I’ll explore his primary, if not exclusive, emphasis on the inevitability of “interpretation,” his alternating insistence on intrinsic as well as subjective (even creative) reading. In my conclusion, I stress Nietzsche’s dual legacy as at once our most influential perspectival thinker and as a passionate seeker, paradoxically enough, of the very truths he more than anyone else put in question.

1

To begin with a paradox: Descartes, the father of modern philosophy, is both an “objectivist” and a “subjectivist,” a radical skeptic who also emerges as an ultra-rationalist. In this case, the dualism can be easily clarified. The skepticism is essentially methodological, a provisional first stage. Descartes overcame his famous “systematic doubt” by “finally” arriving at an indisputable first principal: namely, that in order to doubt, he obviously had to think, and to think he necessarily had to exist: je pense, donc je suis, or cogito, ergo sum—I think, therefore I am. This takes him, and us, only so far. At this stage of the Cartesian argument, the only thing I can know with certainty is my own mind and its contents. Everything else—other minds, the physical universe, including my own body (separate, Descartes insists, from the mind)—can only be inferred from this single absolutely known entity. The result is a radical dualism between body and soul, between my mind (res cogitans) and all external entities (res extensa), between “I” and both the physical world of nature and the social world of other human beings. By emphasizing this chasm between his private consciousness and everything else, Descartes introduced subjectivism into modern philosophy: the famous Ich and Nicht-Ich of Fichte, turned into English by Carlyle and Emerson as the distinction between “Me and the NOT ME.”

Paradoxically, the cogito also introduces what Descartes claims is an absolutely true and certain proposition. For the single indisputably true belief (“I think, therefore I am”) meets Descartes’ requirements for any first principle: it is self-evident and irrefutable; to deny it is to affirm it since to doubt I must think and to think I must exist. The cogito is “true and certain” insofar as it is “clear and distinct” to the mind. Finally, since it is based on “I,” it is not inferred from any more ultimate truth. So what am I conscious of? All I can know, given the absolute distinction between mind and matter, are ideas. Ideas, at least “clear and distinct” ideas, have what Descartes calls “objective reality” to the extent that they refer to external objects. But how can I know whether they do or not, locked as I seem to be in my own private consciousness?

Echoing Anselm’s ontological proof of the existence of God, Descartes undertakes at this point a philosophic version of what Kierkegaard would later call a leap of faith. Having established the certitude of the cogito, Descartes “proves” to his own satisfaction that the preeminent “clear and distinct” idea—that of God—must have a cause as real as the idea. The perfect idea, in short, must have a perfect referent:an actual, existing, infinite, benevolent deity. Such a perfect Being would not maliciously plant in his creatures clear and distinct ideas intended to deceive us. Descartes is here engaged in a spectacular, and rather obvious, piece of circular reasoning. Even if the idea of God is “clear and distinct,” our clear and distinct ideas themselves derive from, and depend on, divine sanction. God must exist in order to guarantee the “proof” ofhis own existence. This is the famous “Cartesian Circle”: a logical absurdity exposed by Kant and others, including Nietzsche, most cogently in The Will to Power §436.

Having established God as the guarantor, Descartes—free of his methodological skepticism and residual doubt—proceeds to erect on this divine foundation the whole material world, a fixed and knowable universe. Descartes was a Christian, a Jesuit-trained Catholic. Nevertheless, his philosophy led historically to mechanistic determinism and to a purely rational Deism, in which God as Prime Mover is out of a job once creation gets rolling. The Cartesian universe emerges as a law-governed clockwork (even non-human animals, lacking rational souls, are mere automata) with God as the original stem-winder, and the human mind or soul (in Gilbert Ryle’s famous phrase) the “ghost in the machine”: the sole flicker of freedom in a determined cosmos. This “Mechanico-corpuscular Philosophy” was condemned as sheer “invention” by that Romantic philosopher of dynamic organicism, Samuel Taylor Coleridge. The “invention” was, he acknowledges in Aids to Reflection (1825), anticipating Nietzsche, an immensely valuable “fiction of science.” The problem was that Descartes propounded it “as truth of fact,” and so sacrificed the vital created world to a “lifeless Machine whirled about by the dust of its own Grinding”—an argument amplified precisely a century later by Alfred North Whitehead, in Science and the Modern World (1925), an organicist text celebrating Coleridge and Wordsworth, who transformed Coleridgean philosophy into great poetry, re-enchanting the world of nature.

For Descartes, our understanding of that pre-Romantic mechanistic universe is purely rational, reason being the one human faculty able in principle to gain access to a world which is itself orderly and “rational.” In this scheme, the passions and bodily instincts are a hindrance rather than a help, a blood-dimmed tide clouding our clear and distinct ideas. Further, despite Descartes’ project-initiating subjectivism, our understanding of the universe is not only rational; it is objective and universal. Anticipating Kant and his Categories of the Human Understanding, Descartes argues that human faculties of reason and sensation are, at least potentially, the same for all, regardless of gender, race, historical contingencies, culture, class, and so on. Starting from the psychological privacy of his own mind, Descartes has reached out to embrace—with supposedly absolute understanding and full certitude—an external and re-divinized world as clear, distinct, and orderly as (it comes as no surprise) the nature-schematizing, mathematical mind from which it is inferred. The universe becomes, in effect, a macrocosmic projection of the cogito, Descartes’ own mind writ large. We may wonder just how far we have moved from subjectivism after all.

2

When, following Descartes’ lead, Hegel later declared the whole of reality accessible to human understanding, that “the initially hidden and precluded essence of the universe” cannot “resist the courage of knowledge,” he was accused of “Gothic heaven-storming.” The accuser was Nietzsche (Musarionausgabe, XVI, 82), whose Zarathustra mocks the vaunted “will to truth” of philosophical distorters who manhandle the utterly unformulatable world of flux and fluent becoming, attempting to comprehend and even dominate it through crude simplification. This “will to the thinkability of all being” by those who doubt “with well-founded suspicion” that it is thinkable, is not at all a “will to truth,” Zarathustra insists, but an exercise of the “will to power.” Such philosophers want the world to “yield and bend” to them, to “become smooth and serve the spirit as its mirror and reflection.” (Zarathustra II 12; The Will to Power §517, 520).

This may seem a variation on the Cartesian projection of the cogito; but in Beyond Good and Evil and in The Will to Power (see, in addition to §436, §484, 533, 577-78), Nietzsche was penetrating in his critique of Descartes. That “father of rationalism” is described as “superficial” since “reason is merely an instrument” (Beyond Good and Evil §191). In launching his assault on the Cartesian ideal of reason as a “pure” and “objective” faculty, Nietzsche characteristically struck through the mask, selecting as his primary target the very foundation –which, for Descartes, is God himself, the guarantor. Indeed, Descartes had initially separated mind and body, spirit and matter, in an attempt to reconcile his mechanistic science with his religious faith. The Judeo-Christian God was famously if prematurely given his last rites by Nietzsche. But his madman’s announcement in The Gay Science that “God is dead” was for Nietzsche himself as elegiac and terrifying as it was liberating—no Enlightenment witticism but a personally painful conclusion he compared to “tearing out the fibers of my own heart.” That madman who ran through the marketplace seeking God announces: “We have killed him—you and I.” As God’s murderers, we are left bewildered, reduced to a series of vertiginous and unanswerable questions:

What did we do when we unchained this earth from its sun? Whither is it moving now? Whither are we moving now? Away from all suns? Are we not plunging continually? Backward, sideward, forward, in all directions? Is there any up or down left? Are we not straying as through an infinite nothing? Do we not feel the breath of empty space? Has it not become colder? Is not night and more night coming on all the while? Must not lanterns be lit in the morning? Do we not hear anything yet of the noise of the gravediggers burying God?…God is dead. God remains dead. And we have killed him. (The Gay Science §125)

With God “dead,” we are left with Descartes’ initial subjectivism and skepticism without his saving and sanctioning deity. The result has been the post-Nietzschean world of modernism and postmodernism: a contingent world torn from its divine mooring—“unsponsored, free,” as Wallace Stevens would put it in his notably Nietzschean poem, “Sunday Morning.” With the earth unchained from its sun, untethered from God and from Absolute Truth, we are condemned to be free, existentially and—by a crucial and influential extension—linguistically.

In his groundbreaking 1976 book, Of Grammatology, Jacques Derrida acknowledged deconstruction’s debt to Nietzsche, who “contributed a great deal to the liberation of the signifier from its dependence or derivation with respect to the logos and the related concept of truth” (31-32). Derrida’s argument, with its radical metaphysical and linguistic skepticism, rests on the insistence that there is no logos, no ultimate referent or “transcendental signified” outside the linguistic system, and therefore nothing to anchor or “fix” the “undecidable,” infinite “freeplay” of language. The absence of a “transcendental signified” extends “the domain and the play of signification indefinitely.” Derrida’s terms derive from Saussure’s Course in General Linguistics; but once we set them in the context of his absorption of the work of Descartes and Nietzsche, we see that at bottom they constitute God-talk—“in the beginning,” says the apostle John, “was the Word [Logos].” Following Nietzsche, but apparently with none of his metaphysical anguish, Derrida cancels Descartes’ “ultimate referent,” the “transcendental” Being “signified” by our “ideas” and language about “God.” All such subjective signifiers refer to—nothing: “an infinite nothing,” as Nietzsche’s madman says, in which we are plunging and straying without direction. There is no “transcendental signified.” God is dead, remains dead, and we are his murderers.

For Michel Foucault, Nietzsche’s Death of God also meant the disappearance of man, his murderer. Others stressed a re-centering on the human. The famous slogan, “Man is the measure of all things,” goes back to the Greek philosopher Protagoras, an ancient axiom revitalized by Renaissance humanism and enshrined in Romanticism, which transfers most of the attributes formerly designating the “divine” to the creative human imagination. But as we are told by Emerson—the American Romantic considered by Nietzsche the major thinker of the age—“nothing is got for nothing.” The apotheosis (or the disappearance) of the human inherent in the concept of the Űbermensch required—though Emerson never accepted the price—the death of God: the dark starting point of much of modern literature and philosophy. W. B. Yeats, who also resisted Nietzsche’s atheism while being deeply “excited” by him, caught in a single line the centrifugal imagery of the Nietzschean madman’s announcement: “Things fall apart; the centre cannot hold.” Unsurprisingly “The Second Coming,” the most frequently-cited modern poem, is also one of Yeats’s most profoundly Nietzschean texts. The radical crisis initiated by the pronouncement of the Death of God has been addressed in a variety of ways by such modern and postmodern continental thinkers as Heidegger, Sartre, Foucault, Deleuze, and Derrida. Whatever their differences, they have one thing in common. Like the Irish poet, all have been influenced by the German philosopher Yeats called in 1902 “that strong enchanter” (Letters, 379).

3

Once the transcendent God who represented and sanctioned absolute and eternal Truth was pronounced dead, the ensuing vacuum was filled—by the mature Nietzsche who first fully emerges in the famous Preface to Beyond Good and Evil (1885)—by two wholly human-centered tasks, interpretation and evaluation, inescapable activities pursued by means of Nietzsche’s pervasive if problematic perspectivism. How does Nietzsche’s influence play out in terms of perspectivism and the need for interpretation? The latter is a particularly vexed issue since Nietzsche, a pioneer in brooding over these questions, has himself been notoriously subject to differing interpretations. Quite aside from the fact that he went through distinct phases (he was even, in his middle period, briefly a positivist), Nietzsche’s volatile and changing thought resists definitive characterization. Back in 1975, in an article in Salmagundi titled “On Truth and Lie in Nietzsche,” I struggled with the ambivalence and contradictions in this endlessly dialectical thinker. In that essay (which I stand by, though, like Nietzsche himself, it goes round in circles), I referred to John Wilcox’s then recently-published Truth and Value in Nietzsche, which made a case for Nietzsche as a cognitivist. A decade later, he was declared a radical relativist by, among others, Alasdair MacIntyre, in After Virtue, and Alan Megill, in Prophets of Extremity, though Megill praised Wilcox’s honesty in presenting passages from Nietzsche’s texts at odds with his conclusion. Megill’s own conclusion was that Nietzsche, whose dialectic exposed every contradiction in even his own argument, is a relativist for whom there is no such thing as a correct interpretation. This is not because any statement is as true as any other, but because there is no such thing “as a thing.” Everything is a “mask” for something else, ad infinitum: precisely what Derrida means by “dissemination” and the endless and undecidable play of signification.

There is, of course, much in Nietzsche to support the conclusion that he was, at bottom, a noncognitivist philosopher for whom values and truths are to be understood in solely in terms of the person who holds them; cannot be supported by bare “facts” or sound reasoning; and are created or constructed rather than discovered. This is in accord with the postmodernist position that “truth” and “value” are not universal, ontological concepts, but subjective, relative, variable. Nietzsche’s reputation as a great liberator—once based on his incendiary language, the audacity with which he punctured hypocrisy, supplied tonic correctives to plebian pieties, and sanctioned the return to heroic, aristocratic values—now derives primarily from his radical perspectivism and the characteristic brio of his formulations. Many of the most striking are to be found among fragments dating from 1885-87, posthumously published in The Will to Power. It is dangerous, as the example of Heidegger’s study of Nietzsche demonstrates, to rely on passages, many though not all of which the author himself chose not to publish. Nevertheless, let us have a representative half-dozen of these on the table, buttressed by a few other of Nietzsche’s most famous, or infamous, “perspectival” passages from texts he did publish.

Refuting the positivist position that “there are only facts,” Nietzsche replies: “no, facts are precisely what there is not, only interpretations [Interpretationen]”; things exist only for human “optics,” and “all the laws of perspective must by their nature be errors.” We “cannot establish any fact ‘in itself’.” Perhaps, he adds, mocking Kant, “it is folly to want to do such a thing” (The Will to Power §481). “The criterion of truth lies in the intensification of power” (§534). For truth “is not something there, that might be found or discovered—but something that must be created” (§552). Nietzsche speaks of the “imposition” of “meaning” from one or another “viewpoint,” claiming that “the essence of a thing is only an opinion about the ‘thing’” (§556). That “things possess a constitution in themselves quite apart from interpretation and subjectivity” is, he says, an “idle hypothesis” that “presupposes that interpretation and subjectivity are not essential.” Could it not be, he asks rhetorically, that “the apparent objective character of things” is “only a false concept of a genus and an antithesis within the subjective?” (§560) Perspective is decisive. “As if,” he exclaims, shocked at the very thought, “a world would still remain over after one deducted the perspective!” (§567) “There are no facts, everything is in flux, incomprehensible, elusive; what is relatively most enduring is—our opinions” (§604).

Though these have become the familiar axioms of the poststructuralist world, even now, they retain much of their original shock value. That last formulation, wittily maneuvered into a paradox enhanced by the dash, is Nietzsche at his most ironic and audacious. Even the so-called laws of nature, he says in his 1873 essay “On Truth and Lie,” are “regulative fictions,” scientific vestigia of mythological dreaming, schematic impositions upon the chaos of the actual. Far from determining an interpretation, “facts” are shaped by our interpretive constructs. This may seem to resemble Kant; but, for Nietzsche, man’s “truths” are merely “his irrefutable errors,” for all of life is based on “semblance, art, deception, points of view, and the necessity of perspectives and error” (The Gay Science §265). Our appeals to “objectivity” are actually expressions of “subjective will”—inventions of our acts of interpretation, outside of which there is “nothing.” And yet, will includes the “will to truth,” which Nietzsche, an “immoralist” who is also one of modernity’s major moral philosophers, never quite abandons. We cannot simplify the multiplicity of Nietzsche, at once a mocker of, and a participant in, the quest for truth, enlisting in different contexts under one or the other of these seemingly incompatible banners.

4

We can agree that Nietzsche attacked the Cartesian concept of objectivity, the idealized notion of a “pure” reason, freed from the allegedly contaminating influences of the body, instinct, will, emotion. From Plato on, the Western philosophical tradition has exalted reason over emotion as the knowledge-acquiring faculty. This privileging of Logos over subversive Eros has been exposed by feminists as not only phallocentric but phallogocentric thinking: resulting in the cock-sure establishment of a masculine hierarchy in which “male” intellect and ratiocination are sharply distinguished from and elevated above emotion and intuition, reductively characterized as “female” and stigmatized as inferior. French feminism succeeded in recuperating the power of intuition and the role of the body; but the ultimate reversal, or transvaluation, of phallocentrism has recently been proposed, sweepingly if rather pseudo-mystically and reductively, by American feminist Naomi Wolf in a 2012 book whose one-word title says it all: Vagina. Nietzsche opened Beyond Good and Evil with his own cunning speculation: “Suppose that truth is a woman—what then?” In the Epilogue to Nietzsche Contra Wagner, he adds that philosophic “artists” (and “we have art lest we perish of the truth” [The Will to Power §822]) consider it “a matter of decency not to wish to see everything naked…Perhaps truth is a woman who has reasons for not letting us see her reasons?” Sexist stereotype aside, Nietzsche is making a playfully subtle point: that truth, though never fully attainable, is best pursued, not by direct frontal assault, but, obliquely, perspectivally. This subtlety recalls the misread alternate title to Twilight of the Idols. How to Philosophize with a Hammer does not urge us to wield a brutal sledge hammer; we are to test for hollowness the “idols of the age,” as well as “eternal idols,” delicately tapping “with a hammer as with a tuning fork.”

While some of his prose approximates écriture féminine, Nietzsche is obviously no feminist. However, like Hume and the Romantic poets before him, and William James and others after him, feminists included, Nietzsche resisted, the valorization of Logos and of a supposedly disembodied “pure” reason disconnected from culture, history, gender, the passions—all those filters that get between us and the Kantian ding an sich, that “thing in itself” which Nietzsche dismissed in Twilight of the Idols as a “horrendum pudendum of the metaphysicians.” In the same text, he declares that “an attack on the roots of passion means an attack on the roots of life.” This insistence on the role of the passions crosses gender lines. Emphasizing sublimation rather than extirpation of the passions, condemned (again in Twilight of the Idols) as “castratism,” Nietzsche asserted, in one of the Blakean epigrams in Beyond Good and Evil, that “The degree and kind of a man’s sexuality reach up into the ultimate pinnacle of his spirit” (§175). Consequently, he celebrated, in the projected figure of the Űbermensch, the ideal of power and passion disciplined rather than denied. Emotion, will, instinct, and disciplined passion, far from clouding and contaminating “clear and distinct” ideas, were necessary ingredients in a total—integrated, holistic—human response to the world.

Here, in this case as part of his condemnation of Christianity’s assault on nature and life. Nietzsche once again proves his credentials as a central figure in the Romantic reaction to Enlightenment hyper-rationalism. Accordingly, his favorite targets, with the exception of Spinoza (whom he valued as, in some ways a “great precursor”), were the major idealist philosophers—Plato, Descartes, Kant—along with orthodox Christianity, loftily dismissed in the opening section of the Preface to Beyond Good and Evil as “Platonism for the ‘people’.” However, his earliest, most personal critique was mounted against Plato’s mentor, Socrates, with whom Nietzsche had a complex love-hate relationship. Though a questioner and a dialectician, Socrates was, Nietzsche charged, a dogmatist who presented his views and values, not merely as appropriate to himself, but, in the words of Alexander Nehamas (Nietzsche: Life as Literature [1985], 4), “as views and values that should be accepted by everyone on account of their rational, objective, and unconditional authority.”

Given his reputation as the poster-child for deconstruction and a thoroughly relativistic perspectivism, it is important to point out that Nietzsche opposes, not a quest for truth, but, rather, precisely that dogmatism (whether philosophic, religious, scientific, or ideological) that conceals, from others and from itself, the fact that its particular interpretation is decidedly not the only possible or plausible one, and therefore should not be binding on others, let alone on everyone. So much for the Kantian Categorical Imperative, or any other form of universality. And yet, for all his skepticism, Nietzsche recasts rather than rejects philosophy, and he does not dismiss either science or the will to truth; indeed, he insists that the latter persists, even for those who question its value and ultimate legitimacy (The Gay Science §344, On the Genealogy of Morals III 25). Though, for Nietzsche, truth and values can no longer be considered absolute and timeless, it does not follow that no moral center can hold, nor that truth is not to be pursued or values asserted and assessed. I will return to this central thematic point.

In the meantime, as the preceding paragraph exemplifies, there is no avoiding the problem of vocabulary: the inconvenient fact that any attempt to elucidate Nietzsche’s argument requires the use of terms he himself has displaced, even parodied. It is well to remember (to quote Harvard philosopher Josiah Royce’s “Nietzsche,” a perceptive article posthumously published in 1917) that, “Like both Emerson and Walt Whitman, Nietzsche feels perfectly free to follow the dialectic of his own mental development, to contradict himself, or as Walt Whitman said, ‘to contain multitudes’.” Cognizant of Whitman’s well-known debt to Emerson, Royce was not aware of the extraordinary extent to which Nietzsche himself was indebted to Emerson, and not only for his dismissal, in “Self-Reliance,” of “mediocre minds,” capped by his grand assertion that “a foolish consistency is the hobgoblin of little minds.” That, as Royce rightly implied, was the source of Whitman’s even more audacious question-and-answer monologue in Song of Myself §51: Out-Emersoning Emerson, cosmic Walt asks: “Do I contradict myself?/ Very well then I contradict myself./ (I am large, I contain multitudes).”

Nietzsche’s dialectical mind, anything but little or mediocre, was certainly “inconsistent” in the sense that it was capacious, volatile, and multitudinous enough to entertain apparently “contradictory” positions. That dialectic is nowhere more dramatic and deep-rooted than in his seemingly antithetical perspectives on “truth.” Nietzsche repeatedly expresses, despite his own more-than-occasional tone of vatic certitude, a deep antipathy toward those who claim any monopoly on truth. Indeed, his skepticism prevents him from presenting any of his own views, including perspectivism itself, in a dogmatic manner. If everything is a matter of “optics” and “will,” then perspectivism, too, is just one more way of seeing things, an “interpretation.” Nietzsche admits as much even in describing his own central doctrine, the Will to Power: “Supposing that it also is only interpretation—and you will be eager enough to make this objection?—well, so much the better” (Beyond Good and Evil §22).

Nietzsche is as chameleon-like as the Emerson he adored. The endless twists and turns, the playful subtleties and self-cancellations of his texts, may seem to anticipate the thoroughgoing relativism we associate with deconstruction. Nevertheless, Nietzschean perspectivism does not imply that any interpretation is as good as any other; the fact that many points of view are possible does not make them equally legitimate. Though he insists that even one’s most passionately-held convictions must remain provisional, Nietzsche also assumes that, in some sense, his own theories are valid, and he repeatedly posits a hierarchy of values. The activities of interpretation and evaluation may be limited to the humanly possible or conceivable, but, as Richard Schacht memorably put it in “Nietzsche’s Kind of Philosophy” (1996), “this does not doom all ways of making sense to perpetual parity, none of which may lay any stronger claim to the notions of ‘truth’ and ‘knowledge’ than any others, like the Hegelian ‘night in which all cows are black’.” Going further, Nehemas insists that Nietzsche’s perspectival emphases do not “imply that we can never reach correct results or that we can never be ‘objective.’”

5

Indeed, when it comes to the interpretation of texts rather than of “things,” Nietzsche can occasionally turn almost sternly objectivist, claiming that we can produce an account freed from subjective limitations and biases. Attacking theologians as bad philologists, Nietzsche describes philology (his own original “field,” his expertise in which won him a university chair at the unheard-of age of twenty-five) as “the art of reading well—of being able to read off a fact without falsifying it by interpretation” (The Antichrist §52). In his original note (The Will to Power §479), he had described this ability to “read off a text as a text without interposing an interpretation” as “the last-developed form of ‘inner experience’—perhaps one that is hardly possible.” It is “hardly possible” for his more skeptical heirs to follow the leader here. Nietzsche is, after all, the master perspectivist and linguistic skeptic to whom homage is paid by all anti-foundationalist modern thinkers: by Derrida and the deconstructionists; by Stanley Fish and other reader-response critics; by Foucault, Nietzsche’s heir as a genealogist of power; and by such neo-pragmatic philosophers as Richard Rorty. Is Nietzsche, of all people (they might ask), really claiming that texts—at least some texts—are in effect “transparent,” requiring only good reading without the intrusion of “interpretation”? If “there are no facts, only interpretations,” what can Nietzsche possibly mean in such “objectivist” passages? What he means, I think, is that, if we are “good” readers, we submit ourselves to the text, letting what is there come through without precipitously imposing on it a falsifying interpretation, distorting it to suit our particular purposes—whether to satisfy an arbitrary whim or to make it serve our vested interests. The text, one might say, has something resembling “rights” of its own, which ought not to be violated by readers abusing their interpretive freedom. On this point, Nietzsche would concur with John Milton’s famous distinction in Sonnet XII: “License they mean when they cry Liberty.”

Though postmodern philosophers and literary critics often blur that Miltonic distinction, confusing many with any, there is a difference between multiplicity and what Yeats called “mere anarchy.” In Of Grammatology, the founder of deconstruction himself calls authorial intention an “indispensable guardrail… protecting” readings from the wilder excesses associated with his term “freeplay” (158). Of course, Derrida adds that the problematics of figurative language itself, with its catachreses and aporias, subtly undermine an author’s intention. But then who among us believes, after absorbing Nietzsche, that complex texts inevitably say precisely what their authors intended? Our sophistication in these matters reflects part of the ambiguous legacy of Nietzsche, aware in his twenties of the pervasively figural nature of language. In a now-celebrated 1873 fragment, “On Truth and Lie in an Extra-Moral Sense” (Musarianausgabe, X, 189-215), the most significant portion of which has been made conveniently accessible by Kaufmann (Portable Nietzsche, 42-47), Nietzsche argues that “the first laws of truth” were furnished by the invention of an arbitrarily “fixed” designation of things, a “linguistic legislation.” “What, then, is truth?” asks the young Nietzsche (repeating that question of Pilate he thought “the only saying that has value” in the New Testament ([The Antichrist §46]). “Truth,” he answers, in an often-quoted sentence, is “a mobile army of metaphors, metonyms, and anthropomorphisms—in short a sum of human relations, which have been enhanced, transposed, and embellished poetically and rhetorically, and which after long use seem firm, canonical, and obligatory to a people: truths are illusions about which one has forgotten that this is what they are….”

While such illusions and “necessary fictions” are, as the noncognitist Nietzsche often insists, valuable, “life-promoting,” even necessary for our survival (Beyond Good and Evil §4), they leave little room for faith in the stability of language. Yet, in praising “the art of reading well,” Nietzsche does not advocate, as he so often does, creative ingenuity, but close attention to what is there, present in the text. But what—to employ the rhetorical question he raised about “things” in The Will to Power—is “there” once “interpretation” has been deducted? Even if language were more stable than it seems to be, our engagement with a text would still, necessarily, constitute an act of interpretation. What choice is there? Since Nietzsche resists any dogmatic claim to univocal truth, there will always be alternative readings, but interpretations, like perspectives themselves, are not egalitarian. Some will be better informed, more comprehensive, more insightful, more “elevated,” than others. Comprehension, never complete or absolute, can be enhanced. An “interpretation” may even turn out to be—accurate!

6

Let us return to the notion of “reading off” a text without imposing on it a falsifying interpretation. In such cases, Nietzsche is dealing, not with “natural” objects in the universe, but with human artifacts—whether a literary text or a theory about nature—that have been produced by human will and skill, and are thus accessible to human construal. This contrast between the physical world of nature and humanly-conceived and constructed artifacts recalls another poem by Wallace Stevens, his gnomic “Anecdote of the Jar”:

I placed a jar in Tennessee,

And round it was, upon a hill.

It made the slovenly wilderness

Surround that hill.

The wilderness rose up to it,

And sprawled around, no longer wild.

The jar was round upon the ground

And tall and of a port in air.

It took dominion everywhere.

The jar was gray and bare.

It did not give of bird or bush,

Like nothing else in Tennessee.

Like William Paley’s famous watch lying on the ground as a supposed demonstration of “intellectual design,” or the geometrically precise monolith in Stanley Kubrick’s 2001, Stevens’s jar stands out—ordered and unlike anything else in the surrounding “natural” world. Nietzsche might say that an art critic could offer an expert, even “accurate,” account of that round, gray, bare aesthetic artifact, but not of the alien, “slovenly wilderness” sprawling around it. Reading this poem, as in contemplating its precursor, Keats’s “Ode on a Grecian Urn,” we are implicitly being asked to consider which of the two, Art or Nature, is to be judged “superior”—here, the human-made jar, or the wilderness in which it is delicately “placed” (momentarily reducing the whole of vast “Tennessee” to a table or shelf). Certainly, the artifact exerts power. The “slovenly wilderness,” which “rose up to it,” and “sprawled around, no longer wild,” seems tamed, almost civilized, by the imperial jar, which, being “tall and of a port in air,” unsurprisingly “made” the wilderness “surround” it, and “took dominion everywhere.” Yet, “gray and bare,” the jar is static, sterile, lifeless. Bereft of the animal procreant urge and vegetative vitality “of bird or bush,” it emerges, though still unique (“Like nothing else in Tennessee”), as singular in a negative as well as a positive sense. And yet, and yet, this diminutive, slightly comical artifact (“round upon the ground”) remains the imposing and orienting center, the still point, around which that otherwise inchoate nature is arranged. Stevens’s cryptic anecdote itself remains—deliberately—ambiguous, but the traditional issue raised—the interaction and tension between Art and Nature, Apollo and Dionysius, Imagination and Reality, Platonic form and chaotic but fecund flux—is both determinate and accessible to interpretation, however much interpretations will differ.

Here, and elsewhere, Stevens himself seems ambivalent on this crucial question. Nor, in the end, though it has to be taken into provisional account, should an author’s own interpretation be determinative. We who are “good” readers in the philological Nietzschean sense can submit ourselves to such a text as this poem by Stevens—or Keats’s originating Ode, also thematically re-enacted in Yeats’s Byzantium poems—without obsequiously prostrating ourselves before an author’s “authoritarian” power. D. H. Lawrence’s imperative remains valid: trust the tale and not the teller, since, to adapt Pascal in a way that would be approved by deconstructionists, a poem will sometimes have reasons the poet knows not of. Should we not, therefore, strive for the best intrinsic, text-centered reading we can achieve? As Nietzsche knew, indeed insisted, we all have our own worldviews, beliefs, feelings, and perspectives—everything that makes us living, breathing, human beings, and that necessarily affects how we read the texts we read. But, he argues in his philological mode, we should, at least temporarily, set aside narrowly subjective interests in order to submit ourselves to the poem, allowing it to do its aesthetic work before we do it the Procrustean injustice of imposing ourselves on it. We should “interpret” without, for example, reducing a text to a mere springboard for our private speculations, or to a helpless specimen to be submitted to a litmus test of ethical or ideological correctness, or converting it to a Lockean tabula rasa (or an ever-changing etch-a-sketch pad) on which we do our own writing.

This will seem alien to the spirit of the Nietzsche with whom we are most familiar: the perspectival subjectivist who so often imposes, both on what he writes and on his readers, his own unique personality. Indeed, he claims that “every great philosophy so far,” no matter how “objective” its truth-seeking pretensions, is really only “the personal confession of its author and a kind of involuntary and unconscious memoir” (Beyond Good and Evil §6). In short, consciously or unconsciously, philosophers impose rather than discover, “reading into” nature what they want to find. (As Oscar Wilde once wittily remarked of the great poet of nature, “Wordsworth found under stones the sermons he had already placed there.”) If Nietzsche’s own philosophy is also a “personal confession and involuntary memoir,” what does that say about his occasional claims to “objective reading”?

Again, we are back to the problems of “truth” and “error,” “fact” and “interpretation,” and the pervasiveness of perspective. Whether we are reading or merely “reading into,” interpretation is inevitable. Yet the fate of Nietzsche’s own writings exemplifies the damage and distortion that can occur when a text is bent to the will of a reader, especially a strong reader with his or her own agenda. The “Nietzsche” many sophisticated postmodernists know is, to some degree, the construct of Martin Heidegger, laid out in a massive two-volume study (Nietzsche, 1961) based not on what Nietzsche himself chose to publish, nor even on the Nachlass on which Heidegger almost exclusively relies, but, finally, on Heidegger’s own “interpretation”: at once insightful, influential, and often profoundly arbitrary. The reductio ad absurdum comes with Nietzsche’s brilliant heir in analyzing “power”: Foucault, who claims both to understand Nietzsche’s thought and to honor it by knowingly distorting it: “The only valid tribute to thought such as Nietzsche’s”—he writes in “Nietzsche, Genealogy, History”—“is precisely to use it, to deform it, to make it groan and protest. And if commentators then say that I am being faithful or unfaithful to Nietzsche, that is of absolutely no interest” (in Power/Knowledge, 53-54). Of course, it is of interest to those who, while aware of the role of creative reception in a reader’s development of his own project, are disturbed by tortured readings handed down as legitimate “interpretations” of Nietzsche’s texts—texts having some determinate meaning even for Foucault, who, exercising his own will to power, admits to willfully “deforming” them.

7

Our response to things, or people, or “texts,” is neither totally objective nor totally subjective, but a mixture—in which the thing, person, or text may (or may not) have its own intrinsic value. Two Shakespearean passages come to mind. In the famous exchange as to whether or not “Denmark is a prison,” Hamlet says the answer depends on individual perception: “for there is nothing either good or bad, but thinking making it so” (II.ii): a claim echoed by Nietzsche in declaring, in a school essay he wrote at Pforta, that “nothing can be judged except from the viewpoint of the spirit involved in it.” In his most “modern,” cynically “relativistic” play, Troilus and Cressida, Shakespeare presents, in the War Council scene (also II.ii), an exchange between Troilus and his older brother Hector—the Trojan champion and the one admirable character in this nearly nihilistic drama. Discussing Helen, the cause of the war and, in this play, little more than a pretty airhead, Hector declares her “not worth what she doth cost/ The keeping.” Troilus poses a rhetorical question: “What is aught, but as ’tis valued?” That draws from Hector a response relevant to the relationship between “objectivism” and “perspectivism,” a response at odds with that of Hamlet, but no less applicable to the relationship between a literary text and its readers. Rejecting Troilus’s position (here and elsewhere in the play) that value is exclusively conferred by external estimation unrelated to intrinsic merit, Hector replies:

But value dwells not in particular will;

It holds his estimate and dignity

As well wherein ‘tis precious of itself

As in the prizer. ‘Tis mad idolatry

To make the service greater than the god.

The prize and the prizer together comprise “value,” but to disregard the preciousness inherent in the thing itself, or to make the subjective “service” greater than the admired object, would be like making religious worship greater than the deity worshipped. The result—self-admiration or self-esteem rather than admiration of something “precious of itself”—is a subjectivist perversion. It is also a reversal relevant to a variety of postmodernist critics who have shifted authority, and even minimal control, away from authors and texts to—themselves, though even their autonomy is strictly limited given that readers, as most of these critics concede or claim elsewhere, are inevitably conditioned by those contexts Descartes tried to transcend but in which we are all embedded: gender, culture, history….

Hector speaks of the “mad idolatry” involved in making the service “greater than the god,” and it was Nietzsche’s “madman” who announced “the death of God.” In 1977, emulating the master, post-Nietzschean theorists Roland Barthes (“The Death of the Author,” in Image-Music-Text) and Foucault (“What is an Author?” in Language, Counter-Memory, Practice), consciously echoing the Death of God, announced the “Death of the Author.” Freeing text and subtext of “authoritarian” control would be liberating, we were assured by these and other non-mourners at the authorial bier. An intrinsic reader, committed to the autonomy of the work of art itself, would agree. But the French theorists, stressing the subjectivist strand of Nietzschean thought, insisted that what we must come to see as truly autonomous was not the poems, plays, novels or essays we read, but, rather, ourselves, or the deconstructive play of language itself. With the artist removed as art’s enabling and shaping force, power was shifted to individual readers sophisticatedly engaging protean “texts.” The danger of anarchic individualism—anticipated by Descartes and resolved by the Kantian Categories, the shared mental apparatus by means of which all minds perceive external phenomena—was also anticipated by Nietzsche, who, as we shall see in a moment, expanded his optical perspective by calling for “more eyes, different eyes” (On the Genealogy of Morals III 12), just as Stanley Fish, in order to prevent the total anarchy potentially inherent in his reader-response theory, grouped readers in informed “interpretive communities”—linguistically-sophisticated schools of Fish.

There has been an even more inclusive and expansive move away from the individual reader as well as from the autonomous individual text. In the case of the New Historicists (often Marxists or critics adopting Marxian methodology), in whose work the center is often abandoned and the margins valorized, the governing authority has been shifted to history itself—though it is worth noting that this emphasis on history as the enabling factor was tempered by pioneering New Historicist Stephen Greenblatt, in the concluding essay of his 1990 collection Learning to Curse. In “Resonance and Wonder,” he himself wonders if attention to the former, the “resonance” of the temporal network in which a text is enmeshed, hasn’t detracted from attention to the linguistic “wonder” of the work of art itself, its own “internal resonances.” As suggested by the title of Greenblatt’s book, a phrase borrowed from Caliban, there is no better example than The Tempest, interpretations of which have been distorted by over-emphasizing either the romanticized relation of Prospero to Shakespeare himself or the imperial-colonial theme epitomized by the subjection of the “native,” Caliban. As the play’s finest editor, Frank Kermode, concluded in the nuanced final sentence of his chapter on The Tempest (Shakespeare’s Language, 2000): “Of course, it cannot be said that neither of these relationships exists, only that they are secondary to the beautiful object itself” (300). See Appendix for a discussion of modern re-envisionings of The Tempest, and a “Nietzschean” response to them by Harold Bloom.

What is primary or secondary depends on interpretation; a work of art “is like a bow,” said Stendhal, “and the violin that produces the sounds is the reader’s soul.” But what of authorial intention? With the author having joined God among the deceased, some egregious examples of interpretive license have been advanced under a Nietzschean banner. Once we realize that readers, not writers, “make meaning,” and that a text “really means whatever any reader seriously believes it to mean,” the “war of all against all” will be replaced by “tolerance” and the “easy equality of friends.” (Robert Crosman, “Do Readers Make Meaning?” in The Reader in the Text, 162). For all his own emphasis on subjectivist and “creative” reading, Nietzsche would be hard put to muster sufficient contempt for this I’m-OK, you’re OK version of what he called in Beyond Good and Evil §44 “the universal green pasture happiness of the herd.” Pending the dawn of this easy egalitarianism, little “tolerance” is extended to those who try to interpret texts, not as utterly dependent on language or history, or on the inventiveness of readers, but as signifying to some extent what a writer meant to communicate. Derrida did not cavalierly discount authorial intention (a guardrail protecting a reading from going completely over the cliff); but for many poststructuralists, the author, at the mercy of his or her own metaphors, has been completely displaced as an originating consciousness by the deconstructive play of language, with its own uncontrollable, autonomous logic. This can result in readings that are illogical, even silly. Everyone has favorite examples of critical excess—the titles of some MLA presentations often seemed self-parodies—committed by those who too uncritically embrace Nietzsche, Saussure, Derrida, and Foucault. As for uninformed readers who puzzle inordinately over what some poor writer might have “meant”: they were often portrayed as adherents of an intentionalist fallacy exposed almost three-quarters of a century ago by the then-New Critics, or as naive victims of an outdated objectivist delusion—and boring drudges to boot.

8

But, as we have seen, the “patron saint of postmodernism” himself is on both sides of this question—and, paradoxically, in service to some form of “truth.” The philologist in Nietzsche made him an astute close reader, committed to explicating the meaning of a text; in doing so, he was seeking, in some sense, the “truth” of that text. As a moral genealogist, he emphasized the personality of the authors he read, often disclosing, with uncanny psychological insight, the hidden forces motivating them. But, once again, he was seeking the truth, however camouflaged it may have been. Nietzsche would hardly have signed on to the postmodern idea of the Death of the Author, being himself the author of books he described as “written in my own blood”: a rather visceral validation of truth. Yet, this search for truth seems incompatible with Nietzsche’s skepticism about, and play with, language, along with that perspectivism and indeterminism that have been so immensely influential, for good and ill, in shaping postmodern debates over literary theory and the problem of interpretation. The Nietzsche invoked by poststructuralist literary critics and philosophers is the noncognitist thinker who took Socrates and Plato, Descartes, Kant, and Hegel, to task for their objectifying and universalizing of the troubled concept of “truth.” Yet, as my italicization of the word truth in this paragraph is meant to emphasize, dialectical Nietzsche was simultaneously committed to that concept, and to its pursuit.

The very first item in Kaufmann’s Portable Nietzsche, a letter from the twenty-year old student to his sister, celebrates the difficult loneliness of the explorer striking out on new paths in search of truth. Though Kaufmann doesn’t notice, young Nietzsche was in fact following a path paved by his mentor, Emerson, who posed, in his essay “Intellect,” a “choice,” given “to every mind,” between either “truth” or “repose.” Between the two, “as a pendulum, man oscillates.” He in whom the “love of repose dominates,” will accept the creed or philosophy nearest at hand; as a consequence, he gets rest and ease; “but he shuts the door to truth.” In contrast,

he in whom the love of truth predominates will keep himself aloof from all moorings, and afloat. He will abstain from dogmatism, and recognize all the opposite negations, between which, as walls, his being is swung. He submits to the inconvenience of suspense and imperfect opinion, but he is a candidate for truth, as the other is not, and respects the highest law of his being.

We do not have to imagine the momentous impact of such a contrast on the formative mind of the young Nietzsche; that impact is seismically registered in the letter to his sister, which opens with a rhetorical question, and, despite his choice of a lonely quest, echoes Emerson:

Is it decisive after all that we arrive at that view of God, world, and reconciliation which makes us feel most comfortable? Rather, is not the result of his inquiries something wholly indifferent to the true inquirer? Do we after all seek rest, peace, and pleasure in our inquiries? No, only truth—even if it be the most abhorrent and ugly….Faith does not offer the least support for a proof of objective truth. Here the ways of men part: if you wish to strive for peace of soul and pleasure, then believe; if you wish to be a devotee of truth, then inquire.

With this ardent proclamation of a philosophic knight errant, we are in the rarefied company of the most radically authentic, most severe and dedicated spirits: philalethes, friends of truth. For all his noncognitivist perspectivism and denial of “objective truth,” there is no dearth of passages, early and late, in which Nietzsche burns his candle at the altar of truth and expresses unmitigated contempt for the “lie,” a word which, in various forms, appears dozens of times in his work, especially in the late text, The Antichrist (see §8, 13, 26, 38, 42-44, 55, 62).

Theory, though it has become diffuse and often narrowly coterie, is still very much with us. So it is still the case that to so much as mention the “pursuit of truth” in post-Nietzschean, anti-foundationalist quarters is often to be dismissed as chimerical, or condemned as an insufficiently “problematized” hubristic objectivist or a hegemonic reactionary—or, worst of all, to be pitied as clinging to a tattered vestige from the past. Letting the word drop without a bemused smile may risk ridicule by progressive ideologues for whom “truth” is not merely disputed rather than a donnée, but just another lobby, a mask for bourgeois oppression. Like the neo-pragmatist Richard Rorty and other anti-essentialists, I do not believe that one can attain pure objectivity, absolute truth, or any transcendental signified: quixotic ideals that evade the real issue. But neither do I believe that the impossibility of attaining the ideal releases the individual, especially the scholar, from what the distinguished classical historian Peter Green called in 1990, in the Preface to his monumental Alexander to Actium: The Historical Evolution of the Hellenistic Age, “the harsh obligation of striving for it to the best of his or her ability. To do otherwise is as though (to draw a theological parallel) the concept of inherent human sinfulness and fallibility were taken as a self-evident reason neither to pursue virtue, nor to avoid error; or, worse, as indicating that the terms ‘virtue’ and ‘error’ had no significant meaning” ( xvi). It might seem obvious that Nietzsche, as atheist, would resist the “theological parallel,” and, as perspectivist, would respond that the pursuit of “virtue” and avoidance of “error” had (precisely) “no significant meaning,” since he himself had unmasked and transvalued those traditional terms. And yet, as we have already seen and will again, it is not at all that simple.

Green was alluding to the poststructuralist ethos then dominating some American universities, a climate in which scholarly research was (and sometimes still is) seldom or never a “disinterested” project; in which “facts” (a dubious concept to begin with) were sometimes concocted or altered to serve a political purpose; in which ethnicity, gender, and other collectively subjective factors were routinely “privileged” over scholarly “objectivity.” This skeptical perspectivism—much of it derived from some, though not all, of Nietzsche’s texts—has in many ways been beneficial. It has exposed the role of “power,” including the power of conscious and unconscious bias; punctured much essentialist afflatus; and provided a tonic corrective to disembodied Cartesian rationalism. Intellectual forces unleashed by Nietzsche have also given the lie to Kantian things in themselves, or “knowledge in itself,” including the futile attempt, in Leopold von Ranke’s phrase, to describe history “as it really was.” Still, as we have seen, this is not the whole of Nietzsche. In the very passage of On the Genealogy of Morals (a passage to which I have already alluded) in which he advised his fellow philosophers to “guard against” such “snares,” he insisted on not one, but two “optical” points:

There is only a perspective seeing, only a perspective “knowing”; and the more affects we allow to speak about one thing, the more eyes, different eyes, we can use to observe one thing, the more complete will our “concept” of this thing, our “objectivity,” be. (III.12)

The scare-quotes are still required; but in our aspiration toward elusive truth and knowledge, surely it is more fruitful to deploy a wide range of perspectives rather than restrict ourselves to a single viewpoint likely to reflect our most egocentric interests. This multi-perspectival approach (“more eyes, different eyes”) to greater plausibility by means of a convergence of viewpoints resembles what the physicist Niels Bohr called “complementarity.” To dismiss this cumulative, ever-more-complete attempt to approximate “objectivity” is to license and even validate any “subjective” position, no matter how narrowly limited. Even demonstrable error—at worst, dangerous nonsense (dinosaurs walking the earth with humans, preposterous conspiracy theories, Obama as non-citizen)—becomes someone’s unassailable “truth” when one’s perception is not only influenced or inflected but totally determined by a single perspective: one’s political ideology or religious belief, gender, class, culture, or ethnicity. For example, dead white males who long conflated “the way things are” with their own myopic but hegemonic perspective have spawned, as merely apparent opposites, more conscious though equally biased successors among extremists implementing a self-segregating doctrine according to which culture and scholarship are determined by gender, race, or ideology.

9

Speaking personally: shaped in part by Nietzsche, I am a perspectivist. I’ve also been influenced by a multiculturalism which, taking into account suppressed ethnic perspectives as well as the human experience we have in common, is sensitive to the racist sins of the past—and the present. At the same time, I have not enlisted among those who often seem eager to trash (in the name of broadening) the entire Western tradition via some current “ism”—whether it’s bourgeois-baiting Marxism, or certain strands of radical feminism, or a dogmatic intolerance and exclusionary tribalism that may masquerade as multiculturalism. Such militant and atomizing extremism threatens but cannot undo the positive aspects of any of these perspective-altering ways of envisioning the world. The collapse of the brutal and dehumanizing Soviet version of Communism did not invalidate crucial elements of the Marxian diagnosis of capitalism any more than genuine multiculturalism is discredited by Islamic extremism or by what Henry Louis Gates, Jr. called a generation ago the “ethnic fundamentalism” of certain Afrocentrists who attempted to resurrect and reverse the racist pseudoscience of the past to prove black superiority. Above all, perhaps, the richest insights of feminism, transcending the necessary but transitional stage of monolithic sisterhood, have permanently changed the way we all see ourselves and our world, including much of the literature we thought we knew best.

Still speaking personally, as a literary critic influenced by Nietzsche, I recognize not only the inevitability of “interpretation” but the force of his radical linguistic skepticism, and do in part believe it. Whether accepting or resisting, I have, like every thoughtful reader, been affected by the impact of the perspectivism and skepticism Nietzsche expressed so strikingly more than a century ago. His very omnipresence indicates that few current theories, critical and political, are as novel as their more a-historical practitioners sometimes pretend; one quickly wearied, for example, of the repeated but false claim that what preceded them was a monolithic and dogmatic commitment to univocal, “correct” reading. The influence of Nietzsche has sometimes been baleful, and often deplored. Nevertheless, his most penetrating insights have introduced an exhilarating breath of fresh air. They have sharpened any number of analytical tools and made us all rethink certain facile and complacent assumptions—about power, race, and gender; about concepts and values less permanently fixed than historically and culturally contingent; about language, silence, and the problematic relation of rhetoric to reality; about the impossibility of Cartesian “objectivity” given the tendency to universalize personal or cultural biases. As a teacher of literature, I came to cast a colder eye on the belief, or pretense, that only feminist and minority-culture courses have “political” content. Though I still ardently believe in a canon of great works, a canon evolving rather than static, I have, after reading Nietzsche and those he influenced, become more skeptical of the criteria behind canon-formation—including, at times at least, even the intrinsic aesthetic value I once thought not only the principal but the exclusive determinant of admission into the pantheon of literary works that have “pleased many and pleased long.”

Yet Nietzsche’s legacy remains ambiguous. Which of the two is the more quintessential Nietzsche: the precursor of postmodernism who brought to bear the full force of his skepticism and perspectival optics? Or, however contradictorily, the dedicated seeker of “truths” that he knew could never be fully attained? The whole point of my essay is that the question cannot be definitively answered. Like Shakespeare’s Claudius, Nietzsche is a man “to double-business bound,” a noncognitist and a cognitivist, at once a destroyer and a creator, a transvaluer of values and a great liberator who was, in his own life and thought, not altogether liberated from tradition, and from the quest for “truth.” Nietzsche, who critiqued pity, is hardly one to seek it. Yet, impressed as we are by the insight, acumen and seductive “style” of Nietzsche as a genealogist of error, we cannot help but be moved by the nobility of the haunted and haunting truth-seeker.

After the “festive” opening of “The Free Spirit” section of Beyond Good and Evil, celebrating the “willing-unwilling” love of “error” as indistinguishable from the “love of life,” Nietzsche addressed a “serious word” to the “most serious”: “Beware, you philosophers and friends of knowledge, and guard against martyrdom! Against suffering ‘for the sake of truth’!” There “might be more laudable truthfulness in every little question mark you place after your favorite words and beloved doctrines.” Thus, to “sacrifice for the sake of truth” would be to “degenerate into ‘martyrs,’ crying out from their stages” in “an epilogue farce,” proving that philosophy’s “actual long tragedy has come to an end” (§24, 25). It is an irony worthy of Nietzsche that in contemplating the personal tragedy of his life, one is tempted, whatever the medical evidence, to envision him as a destroyer who, precisely, sacrificed himself on the altar of truth. In “Nietzsche’s Philosophy in the Light of Recent History” (1947), Thomas Mann, himself a supreme ironist, described, as both a “heartbreaking spectacle” and a tragic “destiny,” Nietzsche’s suffering of a “martyr’s death on the cross of thought,” with his “immoralism” best understood as the “self-destruction of morality out of concern for truth.”

Agreeing, I would add that Nietzsche remained one of those who—as he movingly put it in The Gay Science—“still take our fire…from the flame lit by a faith that is thousands of years old, that Christian faith which was also the faith of Plato, that God is the truth, that truth is divine” (§344). Even as a “godless anti-metaphysician,” fearful that the only “divine” thing left was “error,” and that “God himself” would “prove to be our most enduring lie” (§344), Nietzsche, in some profound sense, remained committed, not to the “lies” and life-promoting “fictions” that might have preserved his sanity, but to the inconvenient truths he uncovered in the course of his longing for that lost divine Truth he had himself unmasked. In this same passage of The Gay Science, he notes that the “will to truth” means—and there “is no alternative”—that “I want not to deceive, not even myself; and with that we stand on moral ground.”

But not on dogmatic ground. Discussing “the intellectual conscience,” Nietzsche insisted that “Not to question, not to tremble with the craving and the joy of questioning: that is what I feel to be contemptible” (The Gay Science §2). Ambivalent to the core, Nietzsche objects to that “beautiful sentiment,” the “faith in truth,” retained by the last “idealists of knowledge,” those “in whom alone the intellectual conscience dwells and is incarnate today,” and who “constitute the honor of our age” (On the Genealogy of Morals III 24). But in a still later work, though he again objects to “beautiful sentiments,” Nietzsche insists that

At every step one has to wrestle for truth; one has had to surrender for it almost everything to which the heart, to which our love, our trust in life, cling otherwise. What does it mean, after all, to have integrity in matters of the spirit? That one is severe against one’s heart, that one despises ‘beautiful sentiments,’ that one makes of every Yes and No a matter of conscience. Faith makes blessed: consequently it lies. (The Antichrist §50)

As he had put it in that early “Emersonian” letter: “if you wish to strive for peace of soul and pleasure, then believe; if you wish to be a devotee of truth” (no matter how “abhorrent and ugly” that truth), “then inquire.” Ironically, Nietzsche’s relentlessly inquiring spirit, an honesty exacerbating his illness, may have contributed to his final destruction, since it led to the discovery of dark truths he himself believed were “terrible” and of whose “impossibility” (as he plaintively remarked in a letter of July 2, 1885, to his friend Franz Overbeck) he wished in vain “someone would convince me.”

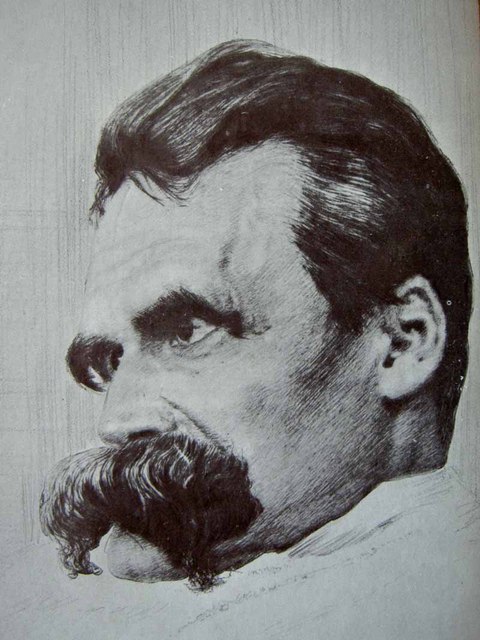

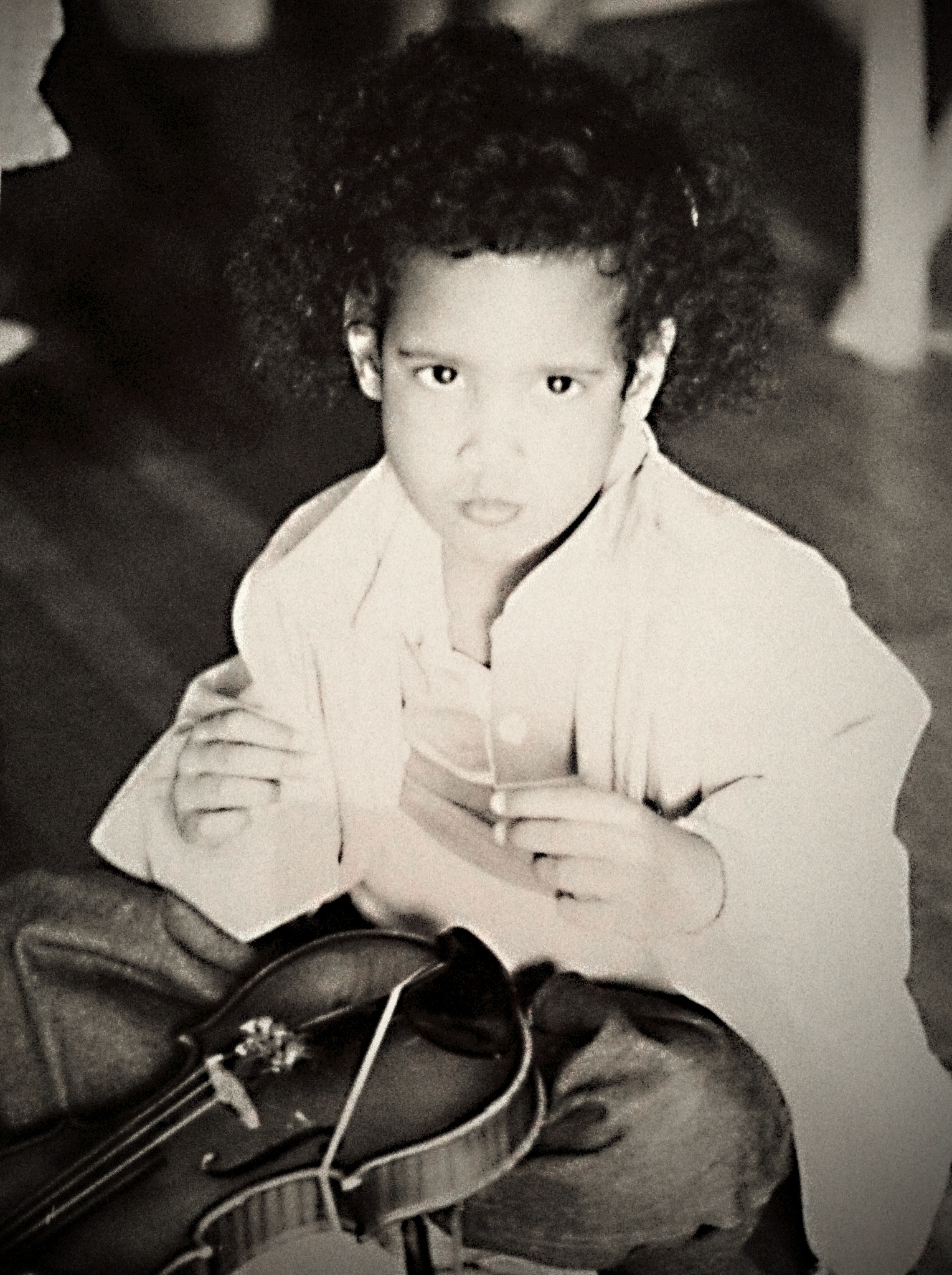

Charcoal sketch of the bedridden Nietzsche, made in 1899, one year before his death after a decade of mental illness. The photograph taken at the time by the artist, Hans Olde, reveals only a vacuous lassitude, the subject’s eyes half-closed and in shadow, a mind adrift. But in his drawing, which otherwise adheres very closely to his photo, Olde opens the patient’s eyes, creating a mesmerizing stare directed mostly inward. The duality of the penetrating gaze — at once half-mad and yet intensely meditative, even “prophetic” — seems evocative of what I have been calling Nietzsche’s ambiguous legacy.

[youtube]http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=alHu-nGqDHY[/youtube]

Hans Olde film of Nietzsche

Appendix

Liberty and License: Re-Reading and Re-Writing The Tempest

As noted in the body of my essay, The Tempest has become something of a critical and cultural battleground, a site for combat between aesthetic and historicist readers. Exercising the hermeneutics of suspicion, many New Historicists depict intrinsic readers who insist on giving priority to what is actually there in a text—say, the text of this Shakespeare play—as both knowing and sinister: “hegemonic” reactionaries conspiring to keep the text’s “real,” if unintended, political meaning from being uttered. That “real” meaning, usually conveyed inadvertently by a politics-effacing author, typically has to do with the dominant (Western) culture’s sexist, classist, and racist suppression of its victims. Along with Defoe’s Robinson Crusoe, The Tempest has been a prime text: criticized, revised, and politically re-envisioned by creative writers, typically from former colonial states. Since such revisionary and creative reading seems notably Nietzschean or Emersonian, I want to register, with reservations, an assault mounted by an eminent contemporary critic powerfully influenced by, precisely, Emerson and Nietzsche.

In the case of The Tempest —its island set in the Mediterranean but reflecting Shakespeare’s reading of Montaigne’s “On Cannibals” and of contemporary accounts of shipwreck and salvation in the Bermudas—Latin-American writers have been particularly active, beginning with Nicaraguan Rubén Dario’s 1898 essay “The Triumph of Caliban,” followed two years later by Ariel, by Uruguayan statesman José Enrique Rodó. French colonial civil servant Octave Mannoni’s influential Psychologie de la colonization (1950) was translated more pointedly into English as Prospero and Caliban. Perhaps most notably, Aimé Césaire of Martinique in 1969 rewrote The Tempest in his own play, Une Tempête, in which Caliban, declaring that “now it’s over,” rebels against the hated “image” imposed on him by Prospero, and finally threatens that “one day,” he will raise his “bare fist” against his Shakespearean master. In Césaire’s revision, master and slave end up staying on the island when the others have left. After many years together, Prospero comes to think of himself and Caliban as indistinguishable: “You-me. Me you.” This might seem to flesh out, even fulfill, those lines at the end of Shakespeare’s play (V.i.275-76) when Prospero reluctantly concedes, “this thing of darkness I/ Acknowledge mine.” But by the time Césaire’s Prospero finally claims identification, Caliban has disappeared, and the last word the audience hears—echoing and altering Caliban’s delusory and ignominious cry of “Freedom!” at the end of Act II of Shakespeare’s play—is the genuinely triumphant offstage cry, “LIBERTY!”

The factors informing such rewritings—ethnicity, economics, social class, colonial history—are among the historical and perspectival elements that condition our responses to the world, and to texts. In the debate with Cartesian and other a-historical conceptions of reason and response as pure, absolute, essentialist, universal, these contingent and conditioning factors will be weighed on Nietzsche’s side of the ledger. Indeed, they will be over-weighed by readers of Nietzsche interested only in the perspectival, noncognitivist aspect of his ambiguous legacy, and in his often brilliant exposure of an author’s hidden and subconscious motivations. My own ambivalence is reflected in Coleridge’s Submerged Politics (1994), a book influenced by, and in part written in reaction to, the New Historicist emphasis on a “repressed” or “invisibilized” content under the surface or “manifest content” of a text: what the author, bound by his or her own limiting perspectives, did not, or could not, say. As the terminology indicates, these theorists have absorbed Freud on The Interpretation of Dreams. The no less overt influence is the Marxian doctrine that works of art are determined by the dominant ideology, and resistance to it. Thus we must read between and probe beneath the lines of a literary work to tease out its meaning. It is, as they say, “no accident” that contemporary Marxian critics repeatedly refer to a text’s “not saids,” its “absences,” and “significant silences.” Nor is it surprising that some readers—politically engaged readers of The Tempest, for example—will want to creatively fill in such absences and silences in ways that remold the text nearer to their own heart’s desires.

In the Age of Theory, a poststructuralist era largely shaped by Nietzsche, most of us will agree that literary texts are not verbal icons hermetically sealed off from the world. They reflect and are influenced by the social and historical contexts in which they are complexly anchored, and they require readers, similarly influenced, to “actualize” them in what Hans George Gadamer calls a hermeneutic or dialogic “fusion of horizons” (Truth and Method, 320). The danger is that in properly asking questions from our present socio-economic horizon, we will also impose answers on the past; or that, in “recontextualizing” works of art, we may temporally limit them to their own historical moment, inflicting aesthetic injury in the process. Often, New Historicist readings, whatever their many illuminations, are closed monoreadings that risk losing the palpable poem in the attempt to recover sociopolitical realities the original author supposedly tried to evade. Marxian theorists—for example, Pierre Macherey in A Theory of Literary Production—insist that these silences and absences are inevitable, ideologically predetermined. Deconstructionists invariably find text-unravelling aporias; what many New Historicists must look for, and invariably find, in “privatized” poems is the effaced “public” dimension, the vestigial politics still lurking in the unspoken but no longer quite inaudible subtext. The claim that often follows, whether explicit or implicit, is that, having ferreted out these buried meanings, we have succeeding in “decoding” the poem, revealing its “absent” and therefore primary level of meaning—the interpretation having the highest priority. Again, Frank Kermode’s admonition is pertinent. Even when, as in The Tempest, the political dimension is actually there, in Shakespeare’s text—however blind earlier readers seem to have been to the layer of meaning often emphasized in our own age—these relations, though they exist in the play, should be “secondary to the beautiful object itself.”

In concurring with Kermode that our actual “highest priority” should be aesthetic, I am not suggesting a simplistic return to the art-for-art’s-sake school of rarified, Paterian “Appreciation.” Certainly, in the specific case of The Tempest, I would not go as far as one of my own cherished mentors, Harold Bloom. Inveighing against the contemporary critical trends he dismisses (deliberately echoing Nietzsche’s famous condemnation of ressentiment) as “the School of Resentment,” Bloom declares: “Of all Shakespeare’s plays, the two visionary comedies—A Midsummer Night’s Dream and The Tempest—these days share the sad distinction of being the worst interpreted and performed. Erotomania possesses the critics and directors of the Dream, while ideology drives the despoilers of The Tempest.” These characteristically emphatic, judgmental sentences open the chapter on The Tempest in Bloom’s 1998 study, Shakespeare: The Invention of the Human. He goes on to make it clear that he is open to such creative re-visitings of the play as Robert Browning’s remarkable dramatic monologue, “Caliban upon Setebos,” and W. H. Auden’s prose address, from The Sea and the Mirror, titled “Caliban to the Audience,” which, though “more Auden than Shakespeare,” catches, as Bloom acknowledges, much of Caliban’s “dilemma” and his “pathos.” What stirs Bloom’s Nietzschean wrath are the political reconfigurings I’ve already mentioned, specifically the transformation of Caliban, “a poignant but cowardly (and murderous) half-human creature,” into “an African-Caribbean heroic Freedom Fighter,” a move Bloom dismisses as “not even a weak misreading.”

This condemnation is less political (Bloom is on the permanent Left) than an allusion to his own long-held literary theory, which celebrates strong, but decidedly not weak, “misreading.” From The Anxiety of Influence on, Bloom has famously apotheosized the “strong reader,” one who brings to bear his own personality, and reads the work of others above all to stimulate his own creativity. Bloom has repeatedly acknowledged that his theory and practice derive primarily from two exemplars: Emerson and his disciple Nietzsche. Emerson insists, in “The American Scholar,” that there is “creative reading as well as creative writing,” and announces, in “Uses of Great Men” (in Representative Men), that “Other men are lenses through which we read our own minds.” At the very outset of Ecce Homo (in the chapter “Why I Write Such Good Books”), Nietzsche claims that, “Ultimately, nobody can get more out of things, including books, than he already knows.” He then goes on, “inconsistently” if prophetically, to complain that anyone who claimed to understand his work “had made up something out of me after his own image.”

This Emersonian-Nietzschean line of revisionary reading Bloom labels “antithetical,” this time borrowing his term from Yeats, who called Nietzsche his “strong enchanter,” and declared in his 1930 diary, “We do not seek truth in argument or in books, but clarification of what we already believe” (Explorations, 310). Bloom champions “strong” misprision (misreading), repeatedly asserting, from The Anxiety of Influence on, that “really strong poets can read only themselves,” indeed, that for such readers “to be judicious is to be weak.” His dismissal is therefore all the more damning when Bloom insists that the post-colonial reinterpretation of Caliban “is not even a weak misreading; that anyone who arrives at that view is simply not interested in reading the play at all. Marxists, multiculturalists, feminists, nouveau historicists—the usual suspects—know their causes but not Shakespeare’s plays” (Shakespeare, 622).

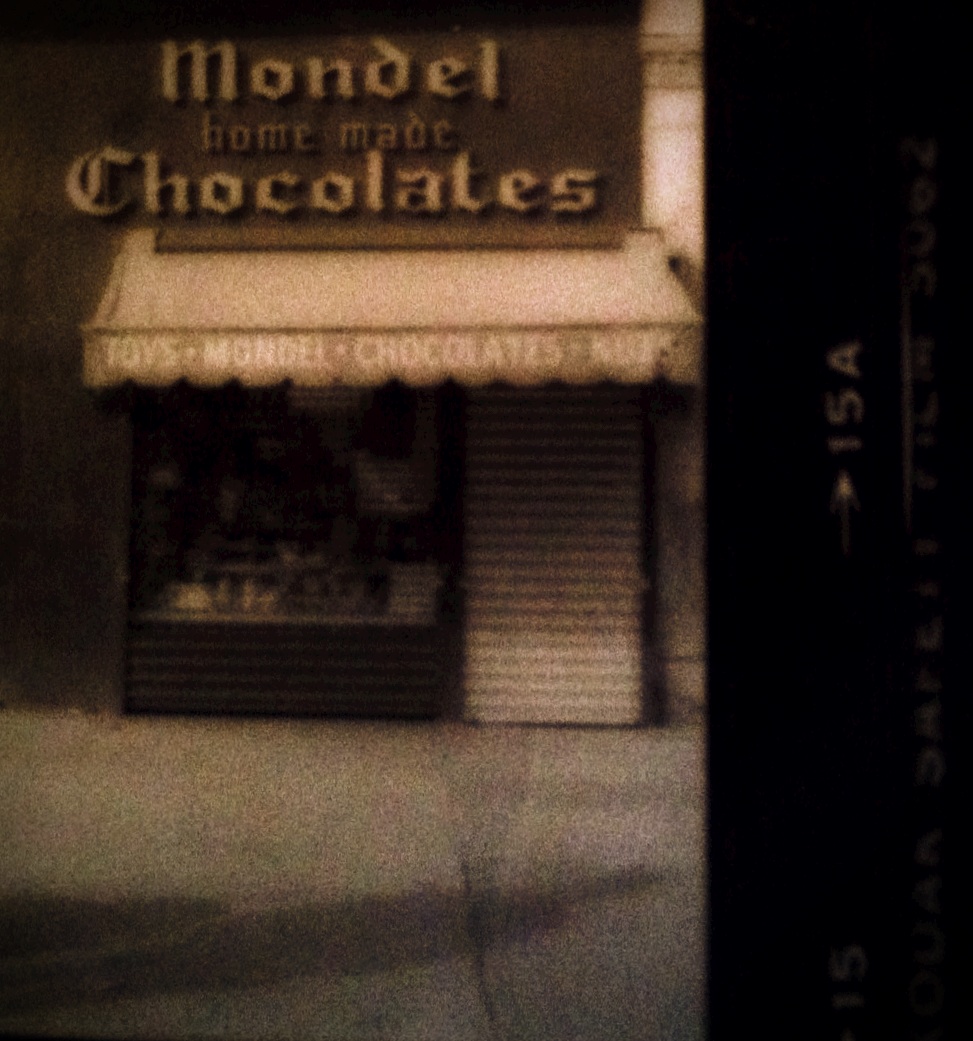

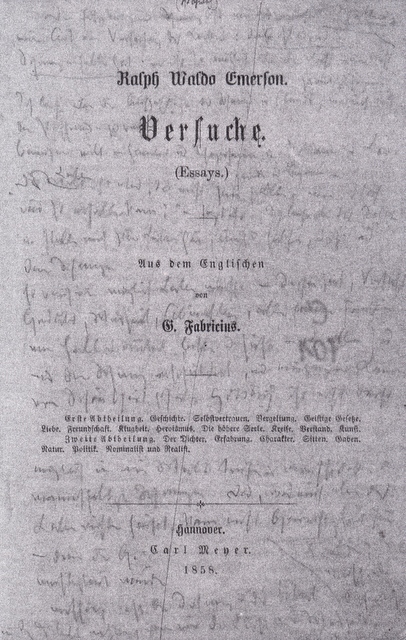

Nietzsche’s copy of an 1858 translation of Emerson’s Essays. His four Emerson volumes are the most heavily-annotated of all the books in Nietzsche’s personal library; in fact, his marginalia became so copious that eventually he recorded some forty passages separately in a black notebook. Though he often transcribed verbatim, at times he shifted to the first-person, almost becoming Emerson, his “Brother-Soul.” Since both Emerson and Nietzsche were adamant champions of utter self-reliance, this creative interaction with his American percursor not only illustrates the general paradox of originality, but incarnates a truth Emerson announced in Representative Men: providing they are kindred spirits, “Other men are lenses through which we read our own thoughts.”