This is a hoot. My old pal Russell Working has written a novel called The Hit, a portion of which was printed in Narrative. Now Russell has produced a brilliantly self-ironic book trailer in which he, his wife and his son act as characters from the book insisting that the book NOT be published. Russell, who worked as a journalist in Vladivostok and has first hand knowledge of the Russian underworld of which he writes, does a turn as a heavy with a thick Hollywood/Russian accent.

Russell Working is a terrific writer, a winner of the Iowa Short Fiction Prize, an intrepid journalist, also a former colleague at Vermont College of Fine Arts.

For your delectation I include also below a short excerpt from the novel, which is not comical at all, but a richly detailed and suspenseful story of memory and revenge reminiscent of Martin Cruz Smith’s great Russia-based thrillers.

dg

[youtube]http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=Cywr00EjsVY&feature=plcp[/youtube]

———–

1

MAMA ALWAYS said it was a sin to throw away bread, a sacrilege to destroy a book. But one day when the tornado sirens were howling on Devon Avenue, Alexei Kuznetsov found three boxes of orphaned books under the awning in front of the Cherry Orchard Deli & Productery, where he worked, and he was unable to save any of them.

He did not know why anyone would leave literature outside a business that dealt in Baltika beer and loops of sausage and jars of slick, pickled mushrooms. Perhaps they had mistaken the deli for the Russian Oasis bookstore down the street and thought the books could be resold. One had to admit the name Cherry Orchard lent itself to confusion.

The sky was boiling, dirty, Jovian, with flashes of lightning in the clouds and distant gray deluges slanting to the south. A pervert wind was molesting two Indian girls, flinging grit and chip packages and attempting to strip them of their saris. The radio said tornadoes had skipped around someplace called Minooka, wrapping a trampoline around a telephone pole and peeling the roof off a strip mall, but the danger had passed here in Chicago. Still, the sirens bayed, their legs snapped in wolf traps.

The abandoned books all concerned Russia and the Soviet Union, but they were mostly nonfiction by Western journalists and translations of classics. Lermontov, Pushkin, Dostoyevsky. The spines were broken, the pages mold-speckled, as spotty as sparrow eggs; besides, everything was in English. When Alexei consulted his boss, Yakov Isayevich told him to trash the books.

“Maybe an American would like them,” Alexei said. “They might learn something about Russia.”

“Such as yourself, you mean? You’re all Yankees, you kids. Pants, hair. You want to compound your ignorance, take them home.” Yakov Isayevich had lived his adult life in Leningrad and Chicago, but the Odessa accent of his youth lent his harangues a comic air. He was bald and mustachioed, and dewlaps hung beneath his veiny chin. “Russia is a thousand-year-long train wreck, that’s all anybody needs to know. Go dump them in back and clear out some space in the freezer, we’ve got a delivery coming.”

Alexei had walked to work. Any books he saved he would have to carry home, along with the groceries Mama had asked him to pick up, and then she would probably make him take the literature to the Goodwill. He stacked the boxes and hauled them all in one trip to the alley in back.

Overnight, somebody had dumped a dead pit bull in the trash, its ears trimmed to ridges of scar so they would not be ripped from its head in a fight. Clearly, it had lost anyway. Its muzzle was gashed and throat torn, but the creature had died clenching a piece of hide in its teeth. The dog lay in a heap of onion peels from a pickled herring dish the girls had made yesterday. On a muggy July day the stench was overpowering: garbage, onions, dog. Alexei began tossing the books in. When one tome on Ivan the Terrible hit the pit bull’s freckled abdomen, the monster gasped, “Huh?” and gave up the ghost, exhaling a whiff of vomit and meat.

As he crouched there, flipping literature up into the trash, a black Hummer H2 with temporary plates pulled up and parked in a tow-away zone, blocking the alley by the refrigerated container that hunkered beside the door. He stood to wave the vehicle on, but the driver set the flashers and got out–whereupon a colony of fire ants spilled down Alexei’s spine and nested, stinging, in his armpits and groin.

A beefy man, mid-forties. Hair grayer than before, mouth drooping, cheeks roughened to chicken flesh by hard drinking. Wearing not a tracksuit anymore, but business attire, with gold cufflinks and a watchband that dangled like a bracelet on his wrist. His buzz cut was receding, leaving an islet of mown stubble where the widow’s peak had once been. His head was narrow, and there was a bump on his brow, the defining characteristic in an otherwise plain and ruddy face.

Alexei had noticed the lump when had last seen the man, eleven years ago in Vladivostok, on a night he and his parents had been heading out to a party. The light was out in the lift, and the doors opened up on a blinding lobby where two men waited. In their hands were bulky black things that began firing bullets into the Kuznetsovs. After killing Papa and wounding Mama, the taller one, this one, leveled his machine pistol at Alexei. His partner grabbed his arm, apparently some kind of wimp who was squeamish about murdering children. “Come on, Garik,” he said, “who gives a fuck about the kid?” That was how Alexei learned the man’s name.

The bump on his brow made you think he must have been knocked on the head. But now, after all these years, it was still there–a cyst or abnormality of the forehead boss. A vestigial horn, almost.

From the Hummer emerged a blonde in low pants that revealed a tattoo of the sun on her sacrum when she knelt to straighten her sandal. Gold bangles, gold earrings with flecks of emerald, a diamond on her wedding ring, worn, in the Russian style, on the right hand. A jewel in her navel like an odalisque.

Alexei half expected Garik to say, “Jesus Christ, kid, what the devil are you doing here?” But he didn’t–why should he, who would associate a teenager in Chicago with the seven-year-old screaming on the floor in Vladivostok eleven years ago?

“Can we get in through this door?” the blonde said.

Garik grabbed a book from Alexei’s hand. “What are you doing?”

“My boss told me to.”

“No, no, no!” Garik cried with an anguished look on his face. “A Russian trashing books? Ignorance!”

“They’re in English,” Alexei managed to say.

“Young man, books are precious,” Garik said. “Leave them, for God’s sake. I’ll find a home for them. So, can we get in this door, or do we have to go around front?”

Alexei said, “If–I don’t–”

“It’s an either-or question,” said Garik.

“You can get in, but customers are supposed to go around. My boss–”

The face silenced him. Garik’s forehead was furrowed except for the skin over the bump, like a hummock left unplowed in a field. Green eyes, the sclera yellowed. A cirrhotic symptom.

“So, you like my face, or what?” Garik said.

“No. I mean, not ‘no,’ I just–”

“I’m flattered, but I’m afraid I’m taken.”

“Oh, Garik, he doesn’t mean anything,” said the blonde. And then to Alexei: “He’s just teasing.” She was in her mid-thirties, perhaps, and had a beautiful face that was flawed by odd, oval nostrils. Her gold necklace had a name on it: MAYA.

Garik shrugged, as if concluding that this simpleton boy was merely tongue-tied in the presence of a businessman of such self-evident success. Deeming this reaction acceptable, he pushed past Alexei and entered the stockroom and kitchen, stinking of vodka and bile. Maya followed, her perfume cloying and chemical, like a Syrian peach cordial.

By the time Yakov Isayevich came out to check on Alexei, his panic attack was spinning to pieces like a lump of watery clay on a pottery wheel.

“Alyosha, how come you’re letting customers in through the back?” Yakov Isayevich said. “Hey, what are you, cataloging a library? Just dump the books and be done with it.” He grabbed two books Alexei had set aside, the Bulgakov and Dostoyevsky, and trashed them before Alexei managed to say that the customer wanted them. Yakov Isayevich shrugged. “What in hell’s hounds is that?” he added, looking in the Dumpster.

“I don’t know, a pit bull,” Alexei said. “Somebody–.”

“Were they fighting it? What’s wrong with people these days?”

Alexei felt a wave of dizziness and grabbed the Dumpster for support.

“Whoa, there,” Yakov Isayevich said. “Are you dizzy?”

“I was in too much of a rush this morning for–”

Amid the aftershocks of the panic attack he could not access the word, starts with a B, the thing with eggs and sausage and toast; and in its place was a blank, like a swearword bleeped out on TV.

“Your mama lets you head out to work without breakfast?” Yakov Isayevich said.

Breakfast. “She’d already left for work.”

“Oi, the poor woman. So you don’t know how to fry yourself an egg? Listen, son, when you get a minute, grab yourself a pastry. So, is this their Hummer? Well, I suppose they’ll be gone soon. Get inside and make yourself useful mopping the floor. Some lady dropped a jar of beets, and everybody’s tracking it all over like a murder scene.”

2

The Cherry Orchard was an old Chicago storefront, long and high-ceilinged, and the odor of salted fish and chicken fat hung so thick in the air it permeated the paint on the walls. The only cherries came in jars, sweet and tart, with pits, the kind Russians spooned into tea. As one entered the main room from the back kitchen and office, a refrigerated counter on the right extended almost out to the front window. To the left was a wall of shelves, interrupted by a doorway into a second room, also facing Devon Avenue. Along the ceiling were posters advertising beer and pelmeni, alternating with American flags. (Unlike Polish or Ukrainian grocers, Yakov Isayevich never posted the colors of his homeland.) The women at the deli counter wore aprons and white hats, and behind the glass were hams, dried salmon, fatback, whitefish, redfish, salads, cakes. Loops of sausage and the carcasses of smoked chickens hung along a mirror on the wall, amid signs that read, “mimosa salad” and “Telephone cards: Russia, Ukraine, Belarus, Poland.” Opposite, the shelves were laden with canned pâté and fish in tomato sauce; bottles of nectar, kvas, vodka, and Moldavian wines; boxes of tea; black rye bread; jars of pickled mushrooms and cucumbers; packages of dried macaroni, barley, and baby food; shrink-wrapped slabs of glazed gingerbread from Tula; and boxes of meringue cookies. Yakov Isayevich had labeled them, in English, “marshmallows.”

The first time Alexei had entered the Cherry Orchard, he must have been eleven, their first winter in Chicago. Mama bought him a slab of Tula bread, and the smell of jam and gingerbread had sucked him in through a puncture in spacetime into a singularity containing a store outside the redbrick kremlin in Tula, where he and his parents had bought picnic supplies for a trip to Tolstoy’s estate at Yasnaya Polyana. Nowadays, he knew nostalgia was commonplace at the Cherry Orchard, you saw it in the faces of everyone who wandered in. That’s what Yakov Isayevich dealt in: longing for a land everyone had spent their lives trying to escape. You could survive for a month in Russia on what it cost you to load up on groceries at the deli, and even by American standards it was pricy (three dollars for a liter of kvas, four for a package of cookies), but for homesick immigrants, the taste of the motherland was worth it. In any event, when one spent eight hours a day in a workplace, the nostalgia disappeared, and the store had long since lost the associations with Alexei’s own vanquished Russia.

He wheeled in a yellow plastic bucket and wringer, steering it with a mop drowned headfirst in the muddy water. Garik was nowhere to be seen, he must have drifted to the other room. A shambles of sugar beets, reeking of vinegar, had been trampled all over, and gory tributaries flowed into the deli counter. Yakov Isayevich had set up a yellow plastic marker with an icon of a man slipping and flying into the air, and there was a warning whose multilingual fluency seemed irrelevant to the Urdu and Malayalam and Russian of Devon Avenue: “CAUTION CUIDADO ACHTUNG ATTENTION.” Alexei knelt to shovel up the beets in a dust pan. As he worked, he maintained a peripheral awareness of the shoppers, mostly women in jeans or skirts he could see through against the light from the window, and when Maya nearly stepped on him, he duckwalked out of her way. “Oi, sorry,” she said, and touched his head. A pair of men’s shoes shuffled in. The left foot detached itself from the floor and scratched the right ankle. Alexei glanced up to see Garik surveying the liquor.

He stood and sloshed the mop on the floor and then in the bucket. A feeding frenzy in a blood-muddied sea.

Garik beckoned Darya Vanderkloot, a cook who sometimes lent a hand at the counter, and sought her counsel on some point concerning the vodka, ignoring her pleas that really, she knew nothing about the subject, she only drank beer and that rarely, Yakov Isayevich was the one to ask. She was in her mid-twenties and dressed to show off her plump, sexy figure, wearing jeans that she apparently applied with a paint brush, yet she was aloof toward the mere males who took notice of her. They were all horny pigs, apparently, for lowering their gaze the cleft that swallowed her zipper in front. Garik nodded as she spoke, his brows compressed, as if seeking, within the fine print of the vodka label, the wisdom of the kabbalah.

Irrationally, Alexei was annoyed at Darya. She shouldn’t flounce about like that for some mafik. She was no supermodel, with her Russo-Mongolian features, but her eyes, grant her that: long-lashed, brown, slightly bugged, their shape emphasized with a mascara brush. Even in summer she was pale as kefir. She said she never tanned because she was afraid of skin cancer. Alexei supposed she was vain about her hair, lush and black.

Garik removed a bottle from the shelf. “Genghis Khan Vodka. The guys would get a kick out of that. Where did you get this stuff?”

“Yakov Isayevich, our boss, sometimes he finds these deals on the Internet,” she said.

“But Genghis Khan!” Garik said. “Why not Attila the Hun cognac or Hitler schnapps?”

“It’s a Mongolian brand,” she said. “They revere Genghis as the Greeks do Alexander. Conqueror of empires. Some people say he was born in Russia, in Chitinskaya oblast. A village called Balei.”

“So, do you have any of those little sampler bottles I could try, to make sure it’s drinkable? Ah, well, it couldn’t be too awful, could it? We taught them how to drink, Mongolians. Surely they’ve learned how to distill vodka properly.”

He decided to buy a bottle, no, three. And a case of the Finlandia, too, in case the Genghis proved execrable.

Hearing the size of the order, Yakov Isayevich, who had been arranging cans on a shelf, moved closer with an expression that said he did not wish to intrude but was at hand, if need be, to assist. But Garik’s stare remained fixed on Darya. He grabbed her upper arm, slipping his fingers between her bicep and breast, as he murmured something to her. Alexei caught the word, “ty”–the informal you–as if she were his girlfriend or daughter. He was old enough, the freaking satyr.

Darya glanced at Alexei pleadingly, but he thought, That’s what you get. If you don’t like it, tell him to take his paws off of you.

Releasing Darya, Garik hummed to himself and shuffled toward the window. He glanced over the shelves, the stand containing magazines and postcards, the refrigerator packed with frozen pelmeni, then returned toward the cash register. Something occurred to him. For the first time he looked Yakov Isayevich in the eye. “Do you cater?”

“Certainly,” Yakov Isayevich said. “We’ve done parties of up to fifty people. With enough notice we could do more.”

Garik called over his shoulder, “Mayechka, did you hear that?” and then realized the blonde was right behind him. On the counter beside his booze she set a basket containing pelmeni, a bag of ginger cookies, and several boxes of tea.

“Oh, it wouldn’t be that big,” Maya said. “Just a few friends.”

“We prefer at least a week’s notice,” Yakov Isayevich said. “More, if it’s a complicated menu.”

Garik turned to the deli case. “‘Israeli salad.’ Why Israeli?”

“It’s just a variety of salad,” said Yakov Isayevich. “If you would like a sample–?”

“No samples for the products of our old allies in Mongolia, but for the ‘Zionist entity’–”

“We make it here in the store. It’s just a name.”

“So how did your authentic Russians of Chicago become so enamored of Jewish cuisine?” Garik said.

Yakov Isayevich hesitated, surprised, perhaps, yet still open to an inoffensive interpretation of the remark, because if something anti-Semitic was implied, it had been so gratuitous. “Perhaps,” he said at last, “because many of them are Jews.”

A dollar coin appeared in Garik’s hand, and he began flipping and catching it. “That’s very interesting, my friend,” he said. “It would explain all the synagogues. I’m not complaining. I used to work for a Jew, and he was the best boss I ever had–a great guy.”

Yakov Isayevich’s ears flushed and a look of alarm flashed in his eyes, as if he was considering how to redirect the topic of conversation without confronting a customer. Removing a towel from his shoulder, he absently bound his right hand in it. Then noticing what he was doing, he blushed and pulled it off.

But Garik himself changed the subject. “So tell me: do you offer any discounts for volume?”

“I can offer ten percent if the order’s over two hundred dollars,” Yakov Isayevich said. “I’m just a small businessman, there’s no profit for me if I go any lower. America isn’t the gold mine people expect when they arrive here, I think you’ll discover that. I’m assuming you’re new here?”

Garik ignored this. He raised the Genghis and examined it against the window, perhaps looking for the sediment found in bad vodka. “What if I just take it?” he said. “A luxury tax.”

Garik smiled at his own little joke but Yakov Isayevich did not join in the merriment. He indicated Alexei with a glance. “I wouldn’t advise that.”

Garik looked at the young man who stood gripping the mop handle. It surprised Alexei to discover that he was taller that the hit man.

“Yes, I’ve met your ferocious young bouncer,” Garik said. “An intimidating youngster, clearly.” There was a touch of benevolent amusement in his tone. “So you’ll, what, mop me to death if I try anything?” Garik aimed his forefinger at Alexei. He cocked his thumb. He said, “Bang.”

“Oh, Garik, pay the man and stop fooling around,” Maya said. Then to Alexei: “Sometimes people don’t get his humor.”

“I don’t know when to shut my trap, she means. No, no, no, no, don’t deny it, Mayechka, it’s true, I’m the first to admit it.”

Garik fished a zippered men’s purse from his suit coat, fumbled about in it, and handed Darya a credit card. He glanced around, as if to make sure everyone had noticed. Perhaps he did not know that every small-time gangbanger on the West Side possesses a credit card. Darya handed it to Yakov Isayevich, who had gone around behind the counter. Leaving his mop leaning in the bucket, Alexei moved a step closer, trying to glimpse the last name on the card, but Yakov Isayevich’s hand closed around it.

“All right, then, make that three bottles of the Genghis,” Garik said. “A case of the Finlandia. A case, no, two of Hennessy. And a couple bottles of this Armenian wine, semisweet. Some Moldavian, too–why not? Some of this Zolotoi Rog: oh, let’s say four bottles. And of course, we can’t ignore the beer drinkers. The Baltika Number 6: how many bottles are in a case? Only twelve? Four cases, then.”

Garik turned to Alexei. “Hey, tough guy, are those Kara-Kums I see on the shelf behind you?”

“We’re out today, but we have other candies, Russian candies,” Yakov Isayevich answered. “Alyosha, can’t you find somewhere else to stand? See, we have–”

Garik silenced Yakov Isayevich by tossing him his keys. “Listen, Gramps,” he said, “maybe you and the boy could start organizing the cases while the girl here rings us up.”

Yakov Isayevich set the keys by the cash register. “Let’s make sure your card goes through. Then Alyosha will help you.”

Genghis, Finlandia, Hennessy: he named off the items as he rang them up. He swiped the credit card, and everyone, Garik included, stared at the cash register, as if in suspense, until it began spitting out a receipt.

Now Yakov Isayevich handed Alexei the keys. “Go carry everything out for the comrade while we finish up.”

#

Out in back, Maya supervised the loading of the vehicle, standing close enough to brush Alexei’s arm with her breasts as she told him how to set boxes just so. When he finished the groceries, he glanced at the books, then at Maya. She rolled her eyes but nodded, so he loaded them in the Hummer as well. When Garik emerged, biting his cuticles, she rushed over and kissed him, lest there be any doubt that he was the bull elephant here. An old Honda with a plastic sheet in place of the rear window puttered up the alley, and the driver, an unshaven man in a striped Russian navy T-shirt, raised his fist to punch the horn. But as he looked over the scene–Garik, the bejeweled blonde, the burly kid loading boxes, the Hummer itself–some assembly line in his head seemed to start up and send down the conveyer belt a conclusion: Mafia. His hand opened into gesture that said, No problem, friends, you carry on, and he backed up the length of the block and around the corner onto North Washtenaw. Alexei went inside for the last box, and when he returned Maya was sitting in the Hummer.

“You’re a strong guy,” Garik said. “You wrestle?”

“Box a little. I’m training for a tournament in a few weeks. In high school I played American football, but I graduated in June.”

“A Russian footballer! Well done, of course. I’ll bet you taught those pansy-assed Yankees a lesson or two. What kind of–how do you say it? What position? I don’t know anything about football except they all dress like cosmonauts. Did you wear one of those helmets?”

“Everyone wears a helmet. I was what they call a linebacker, also tight end on offense, but they hardly ever played me.” Alexei said the words in English–leinbekker, teit end— although they could mean nothing to a Russian; the act of summoning an explanation was beyond him as he stood face-to-face with the killer. “All I did was work my ass off in practice.”

“Well, excellent, nonetheless,” Garik said. “What’s your name?”

“Kuznetsov, Alexei.”

The family name did not register with Garik. It was as commonplace in Russia as Smith.

Garik shook Alexei’s hand, one was unable to avoid it. “Pleased to meet you, Alyosha. Igor Andreyevich. Call me Garik. Been in the States long?”

“A while,” Alexei said.

“Are you a citizen, then?” Garik asked.

“I have a green card.”

“How convenient. Listen, if we do have you guys cater a party, make sure you work that night.” Garik closed the hatch of the Hummer and lowered his voice. “Darya, too, she’s hot. An Internet bride, am I right? Fuck the husband, we’ll show her a good time. As for you, you might meet some people who can help you out in life, if you ever want to do anything other than mop floors for a Jew.”

Garik pulled a dollar bill from his purse and tucked it into Alexei’s shirt pocket, then slapped him on the back. Alexei removed the cash and tried to hand it back.

“I can’t accept tips,” he said.

“Sure, you can, boss doesn’t have to know,” Garik said. “Well, I like this little deli of yours. Like it very much. I’ll be seeing you.”

As Garik drove off, Alexei noted the license number: a temporary Illinois plate, 909F911. Easy to remember. Nine-eleven. He committed it to memory.

He recalled the dollar in his hand. Except it wasn’t a one, it was a one hundred. The bill stank of gasoline. Somebody had stamped Benjamin Franklin’s face with a Web address: wheresgeorge.com.

Alexei tossed the bill in the trash, along with the dead dog, and went inside to wash his hands.

#

So, Garik, again. Short for Igor, patronymic of Andreyevich. But what Alexei needed was a last name. The Beast: as a boy he had seized onto this name during a scripture reading in the church he and Mama attended in Cyprus after they had fled Vladivostok, during that period when she had abandoned her atheism and converted to Orthodoxy. Who is like unto the beast, who is able to make war with him? It had made an impression on him as a, what, seven- or eight-year-old? Seven heads and ten horns. Diadems, and on his head were blasphemous names. They worshiped the dragon because he gave his authority to the beast. And so it had now come to pass that God or fate, having tested the faithfulness of their servant Alexei Kuznetsov, had vouchsafed him a chance encounter with the man whose face had haunted him for eleven years. Were there public records of temporary license plates that would help him locate Garik’s last name? It hit him that he could still find a way to look at the credit card receipt.

Easier said than done. When the deli was busy, there was no way he could crowd in as the cash register rang open and banged shut, and when it quieted down, he did not have access to the drawer. And if he asked somebody to open it, he would have to explain why. But that night, as the end of his shift approached, he sought Darya’s help. There was a lull in customers, and she stood at the front window, her back to the room as she faced the street. One by one, she extended each arm parallel to the floor, and rotated it in a motion that concluded with a graceful twist of the wrist as she brought her splayed fingertips and thumb together, like a lotus folding inward at night. She was wearing a wedding ring on her left hand, American-style, he noticed. He really knew nothing about her.

Noticing Alexei’s stare, she stopped and returned to the counter. “An old dance move,” she said.

“You’re a dancer?” he said.

“Oh, no. There was a student company when I was in university.”

“Listen, Darya, I have a question: did you catch that customer’s surname?”

“Which customer’s?” she said.

“The guy who bought all the booze. Expensive suit, bump on his forehead. Igor Andreyevich, he called himself.”

“Garik the mafik?” Darya said. “No, he didn’t say.”

Somehow it surprised Alexei that she had recognized Garik as Mafia, he had imagined she had been taken in by his airs as a businessman. “Could you sneak a look at the credit card receipt?”

“How come?” she said.

“Just curious.”

“I doubt Yakov Isayevich would want me divulging a customer’s personal information.”

Alexei stared at her for a moment, then walked off.

A few minutes later Darya found him wheeling a hand truck stacked with boxes of ground beef into the refrigerated container; the delivery that had been promised all day had finally arrived just as he was preparing to leave.

“Voskresensky,” she said.

He looked at her blankly.

“That’s the name on the credit card. Igor A. Voskresensky.”

Voskresensky. How simple it had been to obtain the name after all these years. He almost felt the receipt had been there in the drawer from the day he started work here, if only he had thought to look.

“What’s the matter, Alyosha?” she said. “You look so dark.”

“Nothing,” he said. “Just remembering something.”

Yakov Isayevich came humming in through the door. “Well, if it isn’t the two coconspirators, whispering sweet nothings in each other’s ears. I knew I’d find you lovebirds huddled up back here, all kissy-faced and–”

Darya walked out on him mid-sentence and slammed the steel door behind her.

3

That evening as Alexei walked home just after eight, the air everywhere, from the store to the street to the apartment, was dense with dark matter that seemed to warp the buildings and trees, boiling up gusts of gaseous brick and bark were drawn back into the source like solar prominences. The afternoon storm had blown off and the sky was clearing. The moon had risen at an altitude of forty-eight degrees, a distorted sliver of it orbited four hundred thousand kilometers out. It had reached first quarter just over an hour and a half ago, he recalled with some surprise, as if the appearance of Garik would have interfered with the waxing and waning of the moon.

The third-floor hallway of his apartment held a confluence of odors: of somebody’s curry dinner, of the shoes (sixteen of them) outside a Jordanian cabdriver’s door, of the dinner Mama had baked–beef and potatoes and sour cream and cheese. She liked cooking this dish because she alone could prepare it to Alexei’s satisfaction, and it pleased her to watch him devour a full casserole pan in two sittings. When he entered the apartment, Mama laid aside her copy of Inostrannaya Literatura and rushed over to relieve him of his grocery bags as he stepped out of his shoes.

“Rabbit, I was calling you, why didn’t you answer?” she said. “Well, how was I supposed to know you’re on your way home if you don’t set down the bags and take my call? Come on, dinner’s ready.”

Objectively speaking, forty-one wasn’t that old, but Vera Anatolyevna lived like an elderly widow for whom the world was a trial best avoided. She hennaed her hair, and only snorted when he told her that in America such clown-red hues are affected primarily by artists, anarchists, and spiky-haired lesbians. In Chicago, where the heating always works, she dressed in a babushka’s summer housecoat year-round. Once slender and beautiful, she had thickened and aged beyond her years. She worked as a cleaning lady and cook in a women’s shelter, but otherwise she seldom left the apartment except for forays to the bookstore or church, where, after kissing the icons, she always hid herself behind a pillar back in the saint-crowded gloom. She insisted her disfigurement was so horrific that it caused passersby to gape and skateboarders to stumble into lampposts and strangers in banks to blurt out, “What happened to your face?” but in truth her scars were hardly noticeable. There was a dent in the right temple where the bullet had entered, and it had left through her left eye without touching her brain, thank God, so there was no exit wound, only a glass eye that could pass for the real thing except when her socket began weeping. On such days she left the incredulous orb in a tumbler on her nightstand, and she wore a flesh-colored eye patch to cover the collapsed lid. He had given up trying to convince her that she could lead a normal life if she would just forget about other people’s reactions. Yes, easy for him to say. But if one wished to talk about appearance, the real problem was the increasing hardness of her face, and that was self-inflicted: the bags under her eyes, the violet tinge to her nose, the spider veins creeping across her cheeks. A drinker’s face. No doubt she was unaware of the worsening of her looks. The only mirrors in the apartment had been on the medicine cabinet in the bathroom, but Mama had made Alexei remove the reflective triptych, exposing shelves cluttered with toothbrushes and razors and a tube of triple antibiotic cream. He kept a mirror in his backpack so he could comb his hair or check for bleeding zits after shaving blind in the shower.

Mama touched the skin between his eyebrows. “I wish you wouldn’t scowl all the time, you’re getting permanent frown lines at eighteen years old.”

He flashed an insipid smile, and she laughed. They lugged the grocery bags back to the kitchen and sorted everything into the refrigerator and cupboards.

“I know I annoy you with my calls,” Mama said, “but it’s just that there are gangs out there and I worry. I saw a program on TV. Black Gangster Disciple Nation, Mafia Insane Vicelords: who comes up with these names? Conservative Vicelords, it sounds like an Italian political party. Listen, a babushka was raped in a home invasion last week, six blocks from here.”

“I’m sure that had nothing to do with gangs, Mama, it was just some maniac,” he said.

“That’s supposed to comfort me? The point is, I can never relax when you’re out.”

He dumped a bag of flour into a plastic container where the mice couldn’t get to it. “Mamul, listen,” he said, “I need to tell you something. Today–”

“Here, open this, would you? My wrists are hurting again.”

Mama handed him a brandy bottle, and he twisted off the cap. She splashed two hundred milliliters into a crystal carafe and added a shot into a dainty liqueur glass with a stem. Despite Alexei’s age, Yakov Isayevich let him take home whatever spirits Mama requested. A tab was kept, but whenever Alexei brought a payment from his mother, however paltry, Yakov Isayevich would mutter in embarrassment and write off the rest of the bill. Mama was the only person to whom he showed such generosity, for reasons unknown to Alexei. Yakov Isayevich seemed to think he was staying within the limits of the law if no cash exchanged hands at the time a teenager walked out of the store with a bottle of Georgian cognac or a case of strong beer. But at the Cherry Orchard they were contemporary Russians, not Soviet citizens of a former generation, and nobody would dream of informing the Liquor Control Commission.

“It’s good you don’t drink,” she said.

Since Alexei had graduated in June, Mama had taken to commenting on his abstinence, often neutrally and sometimes even praising it, but her demeanor contradicted her words. You’re a man, already, join me in a nightcap if you wish.

“I just don’t see the point of alcohol, that’s all,” he said.

“You should join the Mormons. Soon you’ll be wearing a white shirt and tie and that special underwear. I’m teasing, sonny, you’re right. Once you do see the point of alcohol, it’s too late.”

With her glass she clinked Alexei’s mug of water and threw down her cognac à la russe.

“It’s never too late, Mama,” he said.

“Oi, Alyosha, don’t start. So, are you hungry? Good, sit down.”

Mama had eaten earlier, but after bringing him a plate, she served herself a “symbolic portion, for company” and joined him at the kitchen table.

“You were starting to say something,” she said.

At once he knew he could not tell her about Garik. He could not say why, but he needed to sort this through on his own. “Did you hear the sirens this afternoon?” he said.

“What sirens?”

“Are you kidding, it sounded like an air raid at Stalingrad. Were you at the shelter?”

“No, I told you I’d only be working a half-day,” she said. “They need me Saturday. I was home all afternoon.”

“Yakov Isayevich tried to get us to take refuge in the basement, but then we heard the tornado warning was limited to Will and Kendall counties.”

“Maybe I slept through it,” she said.

You always do. Mama refilled her glass from her carafe and fixed her cockeyed, teary gaze on Alexei. She had been in this state for weeks after they had fled Russia for their second home in Limassol, Cyprus. She spent her days in the twilight of the master bedroom, the exterior shutters rolled down to cover the sliding glass doors. Alexei would lie next to her on the bed as a fan on a tall stand sent a ticklish breeze back and forth over them, and they would remain there in silence for hours, holding hands, as her warm cognac breath came and went. It was a fortnight before she even thought to ask a Russian friend to enroll him in an English school. One day he came home with a pocket full of candy and a Japanese comic Ruslan had lent him, but when he arrived, Mama was missing. He took the elevator down and searched the neighborhood for hours, checking back frequently in case she’d come home. Finally long after dark, he curled up on the Persian carpet under the baby grand piano and cried. An orphan now. Oh, Mama! A persistent knocking roused him. He did not think he had slept but there was drool on the carpet, hair on his tongue. At the door, a Cypriot woman with hirsute hands said in English, “Russian lady, Russian lady!” and a great deal more in Greek. She took him by the hand and led him down the stairway. Mama lay passed out on the landing three flights down, her housecoat hitched up to reveal a tuft of pubic hair coiling from her flowered panties. Together, he and the woman got Mama to the lift, dragged her back home, toppled her into bed.

“Sirens, I don’t see what the big deal is,” she said. “You can’t get tornadoes in a city because of the skyscrapers.”

“Mama, that’s ridiculous,” he said. “Besides, there are no skyscrapers on Devon.”

“Perhaps, but I’m still here, along with the rest of Chicago. So what else happened today?”

“Oh, nothing,” Alexei said. “Really, it’s boring to talk about. Stocking shelves. Breaking down boxes. Some idiot shoplifted a bottle of whiskey, but I ran him down while Yakov Isayevich called the cops. No, he was not a gang member, just a stupid kid. For awhile this morning the scanner was acting up so we could only accept cash. Customers become so rude when this happens, they announce they’re going to go to Jewel-Osco from now on. I guess you can’t blame them, but why is it our fault? We’re just employees. Also there was some idiot mafik who came in, kept pawing Darya. Apparently she’s incapable of telling him to keep his hands off her. I’m not going to chaperone her if she can’t even speak up for herself. I wanted to stave his head in.”

“Alyosha, must you speak so violently?” she said. “I won’t have that in my house.”

He gulped a forkful of beef and potatoes. “How was your day?”

“Oh, you know me, focus on the positive,” she said. “There’s hope the clients will escape the abuse the longer they’re with us. Although, sometimes–. That Bengali went back to her husband. Also, there was a Russian, I had to interpret for her, she barely speaks English. Don’t laugh, I’ve done it before! Enough, I don’t like dwelling on bad things. Did you meet anyone interesting?”

Alexei sawed the heel from the loaf of bread she had baked. “Mama, there are always girls in the store, and all of them are married. I don’t think there is a single Russian girl my age in Chicago. Pretty ones, anyway, I’m not talking about Masha.”

“Nonsense, she’s a lovely girl,” Mama said. “Anyway, a mother has to ask.”

Alexei twirled his mug of water on the table.

“Don’t, you’ll spill it. Was Yakov Isayevich yelling at you again? You’re so gloomy.”

“Yakov Isayevich doesn’t bother me,” Alexei said. “If he wants to stress out about everything and drop dead of a heart attack at sixty-five, that’s his problem. I’m just tired, is all. I slept badly again. Five and a half hours. It doesn’t matter, I can get by on that if I snooze on my lunch break.”

“Maybe you should go back on Zoloft,” she said.

“I haven’t had a panic attack in years.”

Then the dizziness and fire ants returned, and Alexei excused himself–“Urgent need”–and hurried to the bathroom, where he sat on the toilet with the lids down, fisting his eyes as he rode out a hurricane of black locusts and burnt straw.

— Russell Working

An excerpt of an earlier version of this novel first appeared in Narrative magazine.

——————

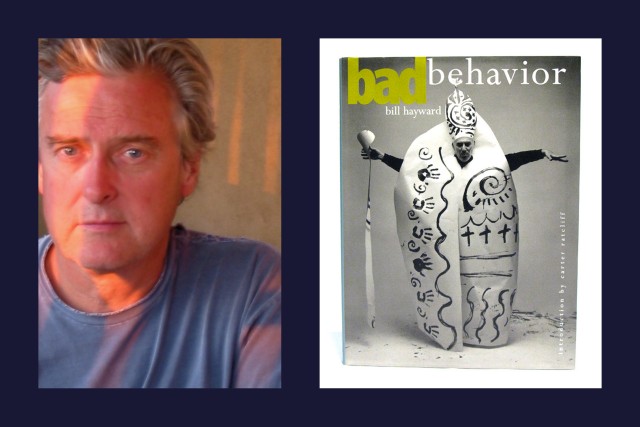

Russell Working is a journalist and short story writer whose work has appeared in publications such as the New York Times, The Atlantic Monthly, The Paris Review, The TriQuarterly Review, and Zoetrope: All-Story.

His collection, The Irish Martyr, won the University of Notre Dame’s Sullivan Award. He was the youngest winner of the Iowa Short Fiction Award, for his book Resurrectionists. He is a staff writer for Ragan Communications in Chicago and has taught in Vermont College of Fine Arts’ MFA program in creative writing.

Russell’s journalism has often informed his fiction. His Pushcart Prize-winning The Irish Martyr,written after an assignment in Sinai, tells of an Egyptian girl’s obsession with an Irish sniper who has enlisted in the Palestinian cause. After reporting on the trafficking in North Korean women as wives and prostitutes in China, he wrote the short story Dear Leader, about a refugee from the North who is sold to a Chinese peasant.

Russell formerly worked as a staff reporter at the Chicago Tribune. There he exposed cops and a Navy surgeon general who padded their résumés with diploma mill degrees, and covered the international trade in cadavers for museum exhibitions.

He lived for nearly eight years abroad in Australia, the Russian Far East, and Cyprus, reporting from the former Soviet Union, China, Japan, South Korea, Mongolia, the Philippines, Turkey, Greece, and aboard the USS Theodore Roosevelt. His byline has appeared dozens of newspapers and magazines around the world, including BusinessWeek, the Boston Globe, the Los Angeles Times, the Dallas Morning News, the South China Morning Post, and the Japan Times. He began his career at dailies in Oregon and Washington.

Laura Von Rosk lives with her dog Molly on a lagoon just outside Schroon Lake, New York. She curates the Courthouse Gallery at the Lake George Arts Project, a gallery dedicated to the experimental and the avant garde.

Laura Von Rosk lives with her dog Molly on a lagoon just outside Schroon Lake, New York. She curates the Courthouse Gallery at the Lake George Arts Project, a gallery dedicated to the experimental and the avant garde.