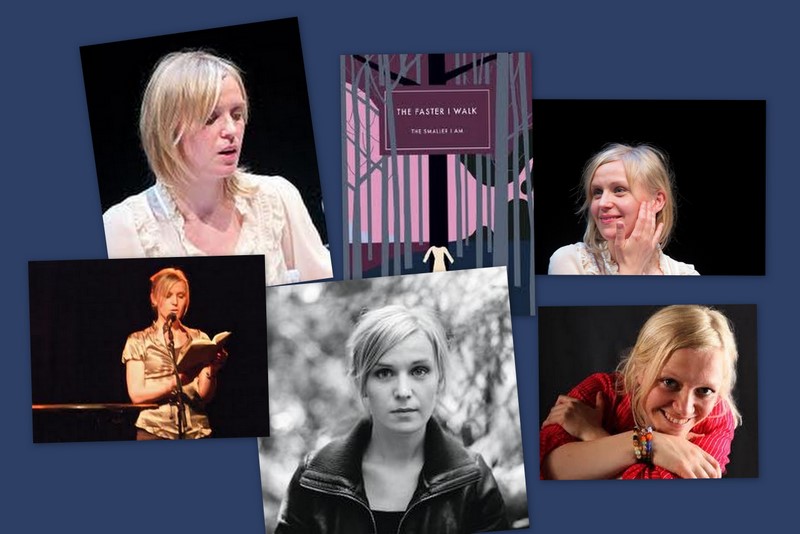

Herewith an essay on Mormonism, diverse spiritualities, marriage, and a contemporary quest to repair a damaged heart. Phyllis Barber is a dear friend and former colleague from Vermont College of Fine Arts. She’s also a Mormon, a product, as she says, of that “all-encompassing culture,” and an adventurous soul. She is the author of seven books: novels, stories and memoirs, including her delightful early reminiscences in How I Got Cultured: A Nevada Memoir and her most recent book Raw Edges: A Memoir. Lately she has been working on a new collection of essays, entitled Searching for Spirit (from which the essay below is taken), about her twenty-year hiatus from Mormonism when she traveled the world and participated in many religious and spiritual experiences with shamans in Peru and Ecuador, Tibetan Buddhist monks in North India, Baptist congregations in South Carolina and Arkansas, goddess worshipers in the Yucatan, with African American congregations, and diverse megachurches. The theme of Mormonism is interlaced with these narratives as well as the belief in the Mormon teaching of a personal God. As Phyllis says, this her “attempt to come to peace with co-existence and reiterate the idea of religious tolerance—God being found in the faces of strangers.”

dg

Part One – 1985

My three sons bolt out the side door, late for school, scraping their backpacks against the door frame which is already scarred. I avoid looking at the pile of breakfast dishes. Cold egg yolk. Blackened crumbs. Drowned mini-wheats. I can’t help notice, however, the specks of yesterday’s cake mix, flipped from the wire arms of the electric beater, dotting the kitchen window above the sink. Later for that. Inside the refrigerator where I turn to find inspiration for tonight’s dinner, an amoeba-shaped puddle of grape juice jells on the glass shelf. I close the door covered with magnets and photos of boys with the-orthodontist-needs-to-be-visited teeth. I leave this messy kitchen, this reminder of my ineptitude which will depress me even more if I think about it much longer.

I need to talk to someone. But who wants to listen? Who would I tell anyway? Maybe I should get on my knees and talk to God but I need to move more than I need to stay still. I need to feel my body alive—arms stretching up and out, blood speeding through my veins. Mid-step in the front hall where family and visitors come and go, I’m struck with an idea.

I turn the corner to the family room. It’s filled with furniture, but because I feel compelled to dance, I’m suddenly an Amazon woman. I push the wing chair to the wall. The sofa as well. Now there’s space, enough space, and it feels as though it might be possible, instead of praying to God, that maybe I could dance with Him somehow, that He could take me in His arms. Today. Right now.

I thumb through my stack of albums until I find Prokofiev’s “Concerto No. l for Piano & Orchestra, Op. 10,” lift the record out of the sleeve, and set it on the turntable. Aiming the needle, I find the first groove and wait for the ebb and flow of the orchestra, the in and out. The three beginning chords cause my arms to pimple with goose flesh. I take two steps to the middle of the room and raise my arms above my head in a circle, fingertips touching.

I move, slowly at first, one foot pointed to the right as if I were the most elegant ballerina in the most satin of toe shoes. At first, my right leg lifts poetically, delicately for such a long leg. The other knee bends in a demi-plié. But as the music swarms inside and splits into the tributaries of my veins and vessels and becomes blood, things become more primitive. I stamp the pressing beat into the floor. I bend to one side and then the other, my arms swimming through air. I’m a willow, a genie escaping the bottle, the wind. I’m the scars in the face of the earth opening to receive water that runs heedlessly in spring. I’m light. I’m air. The magic carpet of music carries me places where I can escape—to the Masai Mara I’ve visited on TV, where bare legs of tribal dancers reflect the light of a campfire and beaded hoops circle their necks, or maybe to the Greek islands I’ve seen on travel posters with their red-roofed white houses stark against the cobalt blue sky and water. The music lifts me out of this minute, this hour, this day. I’m dancing to the opening and closing of the heart valves, to the beat of humanity, dancing, giving my all to the air, giving it up to the room. Whirling. Bending. Leaping. Twisting. Twirling and twirling to the beat. Yes. Dancing. Getting close to what God is, I suspect.

After a dizzying finale where the chords build to a climax until there is no more building possible, the release comes. The final chord. The finale. The sound dies away, as if it had never been there. The room still swirls, passing me by even as I stand still, panting, trying to return my breathing to normal once again. I’m dizzy. I steady myself in the middle of the Persian rug and wonder why Prokofiev had to write an end to this concerto. I can hear the tick of the needle on the record in the black space left on the vinyl. I stand quietly until the room stops with me, until the sense of having traveled elsewhere fades away.

I look at this sky blue family room in our home in Salt Lake City where my husband David and I are raising our children—the family pictures on the wall, including one of Geoffrey, our first son who was born with hemophilia and who died at the age of three from a cerebral hemorrhage. I look at his quizzical expression looking back from behind the picture glass. It’s as if he’s asking, “Why, Mama?” I pause, wanting to speak, wanting to answer him, but words have no meaning. Maybe they never did. My eyes shift to the framed copy of David’s and my college graduation diplomas; the Persian carpet with its blue stain where our son, Chris, spilled a bucket of blue paint when he was two; the sandstone hearth where our son, Brad, fell not once, but twice, and split open his head which had to be stitched together in the emergency room. Everything slipstreams in my peripheral vision: the bookcase with its many volumes of books, psychological tomes, religious scriptures, all of which are supposed to have answers; the leather wing chair peppered with the points of darts thrown when I, Mother, wasn’t looking and before I, Mother, hid the darts in a secret place; the wooden floor which I’m supposed to polish once a week with a flat mop and its terry-cloth cover. I, the Mother, stand here looking at the things which verify my place in the world and also at the evidence telling me that I haven’t always been watchful at the helm—I, the Mother who is supposed to make the world all right for her husband and children; I, the Mother, the heart of the home, the protector, the nurturer. I think I should dance again, turn the music loudly before my mind chases me into that place where I feel badly about myself again.

I learned dancing from my father who loved to polka when Lawrence Welk’s Orchestra played on television and at dance festivals sponsored by my church when I was a teenager. We danced the cha cha, tango, and Viennese waltz. At age twenty-one, I danced myself into a Mormon temple marriage and made promises to help build the Kingdom of God here on earth. I gave birth to four sons whom I dressed each Sunday for church meetings. I tried to be a good wife. I canned pears and ground wheat for bread, I taught Relief Society lessons and accompanied singers and violinists on the piano, I bore testimony to the truthfulness of the gospel countless numbers of times. Yet dancing seems to be my real home—the place where I can feel the ecstasy of the Divine, this dancing.

Last night as I twisted and turned in bed with my newfound knowledge that there’s another woman in my husband’s life and with the realization that things are changing in my marriage, which I thought would always be in place and always be there for me, I felt tempted to jump out of bed, open the blinds, and search the night sky for the letter of the law burnished among the stars—a big, pulsing neon sign that said, “Thou Shalt Not Endure to the End.” Except that’s all I know how to do: persist, endure, keep dancing. Things have to work out, don’t they?

Mormons are taught not only to endure to the end, but to persist in the process of perfecting themselves: “As man is now, God once was; As God is now, man may be.” Lorenzo Snow, fifth president of the LDS Church, penned the often-repeated couplet after he heard Joseph Smith’s lecture on this doctrine. I’ve tried for perfection, but maybe I haven’t thought that word through to its logical conclusion. Maybe I haven’t wondered enough about who is the arbiter of perfection.

Perfection. Freedom from fault or defect. Is that possible? Perfection is a nice idea, but that definition makes the idea of becoming like God stifling. It’s tied to shoulds, oughts, and knots that bind, rather than releasing one to live a full life and to dance the dance. Even Brigham Young said, “Let us not narrow ourselves up.”1 Trying to be perfect when the world and David have no intention of complying with my notions of perfection is killing me.

I hear the telephone ringing. I don’t want to leave this room just yet. I want to bring back the music, to keep God here with me, even if he has places to go, things to do, and I, too, have my responsibilities. But, I think, if God is my Father, then I am his daughter. I need to trust that he’ll always be with me somehow, that there will be a next dance.

Ignoring the phone, I think of something William James said in The Varieties of Religious Experience about how a prophet can seem a lonely madman until his doctrine spreads and becomes heresy. But if the doctrine triumphs over persecution, it becomes itself an orthodoxy. The original spring of inspiration dries up and its followers live at second hand in spite of whatever goodness this new religion may foster, stifling the fountain from which it drew its supply of inspiration.

Why am I thinking about William James right now? Do I suspect I’m caught in the web of orthodoxy? Am I inflexible and is my spring dry? Am I living at second hand—unwilling to consider any other options to my parents’ teachings and my Mormon upbringing? But I don’t feel inflexible when I dance. I’m the fountain that bubbles, even the source of this fountain—the water. I raise both arms to the ceiling as if to lift off, hoping I can stretch into the heavens. “Don’t leave me,” I want to call out, though I don’t say that out loud. “I am with you,” I hear him say, though he doesn’t say that out loud either.

Daylight pours through the windows, exchanging the light in this room for that of the day. My hands press flat against each other in front of my heart, “Thanks for the dance,” I whisper. “Thank you,” I think I hear him whisper back. The telephone has stopped ringing. A floorboard creaks beneath my foot. I can hear the refrigerator humming down the hall. Commerce and industry, motherhood, and wifehood, with all of their demands calling again.

Part Two – 1991

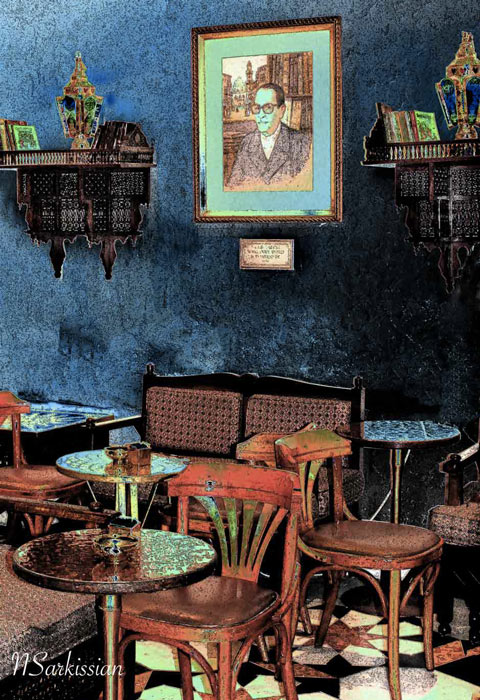

One particular Bedouin catches my attention. He’s carrying plates away from our feast, preparing for after-dinner entertainment. Omar Sharif, I can’t help but thinking. What else does a first-time-in-Jordan, U.S. citizen know—those molten eyes and their hint of “the Casbah?” Of course, this is my movie-acquired understanding. He could be a thousand things, maybe a Muslim appearing for tourists to make ends meet, to feed his children, maybe the leader of a motorcycle gang, or he could be, plain and simply, a wanderer or a gypsy. But it’s useless to care about definitions this evening as we gather in this tent in the desert, two small groups of tourists wanting a glimpse into the mysterious life of a Bedouin.

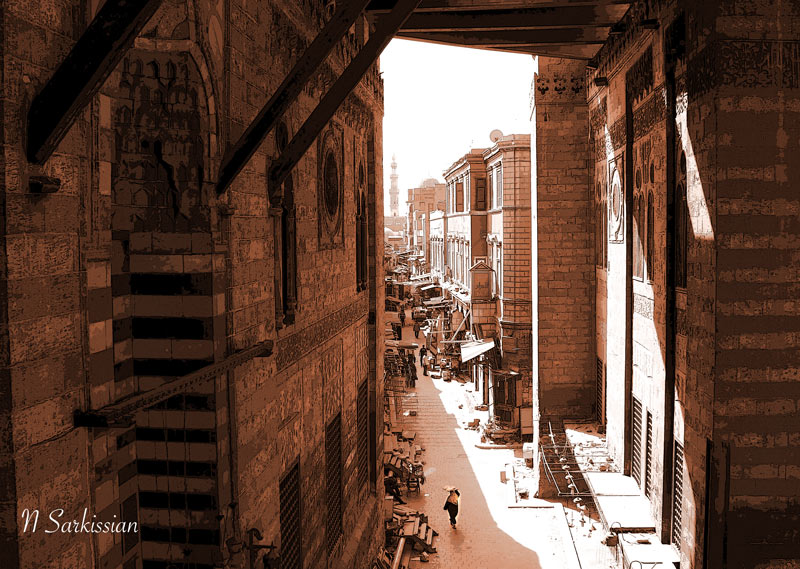

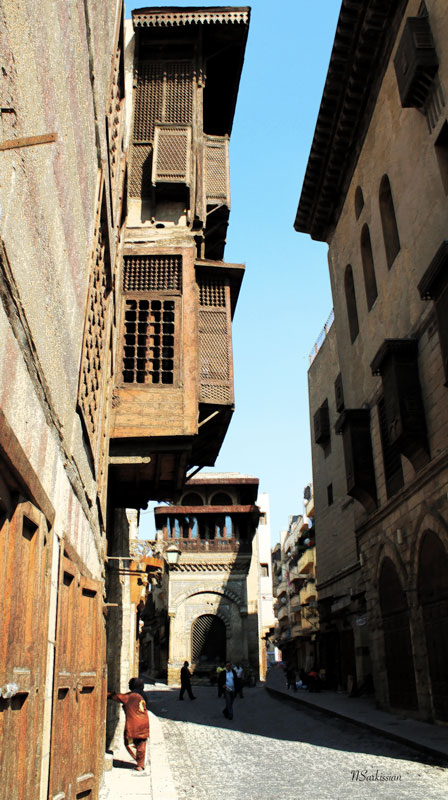

One week before this night, my husband David and I had sailed down the Nile hoping to understand a portion of the ancient wisdom of Egypt. But the Sphinx and the gargantuan pharoahs carved into stone were hugely silent. We could only guess with our clichéd bits of Egyptology—King Tutankhamun, Cleopatra, Rameses, Isis, Ra the Sun King—and our memories from our Sunday School Bible studies: Joseph with his coat of many colors, Pharoah’s dreams, Potiphar’s wife, and Moses, of course Moses.

At nights between visits to Luxor, Edfu, Aswan, on board our sailing vessel, our lively crew, their lithe bodies swaying like river reeds, pulled all of us by our hands to the middle of waxed floorboards. Ouds thrummed; doumbeks pounded. And we danced: a lightening of bones and a suspension of time. We turned and swayed on the boat’s deck until I felt lost in my body—released from my neck, no brain to run the show, swept away by the flow of the unconscious in my flesh and in the other dancers. Nepenthe. A release of cares, such as the fact that David’s and my marriage was on its last legs.

At the end of our Nile run, we boarded a tour bus and headed toward the Sinai Peninsula. We were excited to see the place where Moses parted the Red Sea with his staff, found his way through the impenetrable clouds covering Mt. Sinai, and camped out at the top for forty days and nights, all the time waiting for inspiration. On a cold morning at 4:00 a.m., we laced our hiking boots and set out for Mt. Sinai’s summit, hoping to climb back into the Bible before the Bible was the Bible. Just as the sun slipped over the horizon, we reached the top. With a crowd of tourists speaking every conceivable language, we looked for signs of charred ruins of a bush or crumbled bits of stone tablet. But instead, the mystery seemed to be embodied in the purple, fog-like clouds that bubbled out of the crevices and danced in the valleys between the multiple hills below us. The clouds shifted constantly—a cauldron of mist and fog. David and I agreed this was a superb place for anyone to talk to God.

By mid-morning, we were back to our own exodus from Egypt, heading toward Jordan, our tour bus crossing the Sinai Desert. An hour into this leg of our journey, one woman in the group who had fallen victim to the dreaded tourist’s gambu, shouted at the bus driver to stop, then bolted for the door, telling us she’d be right back, don’t interfere. While we waited for her return, someone caught sight of movement on the wind-shaped, sandy horizon. It looked like the rising of three small ships from the sea. Everyone made their guesses of what this was until we could see three Bedouins riding camels, their heads wrapped in scarves, their feet covered in soft leather.

Bedouin—the word with mystical, romantic properties. My lips formed the word again: “Bedouin,” as several of us climbed off the bus, partly to distract the newcomers from our hapless tour mate who’d hidden on the other side of the bus, and partly from curiosity. I held a packet of pencils in hand, something I’d brought to give to children instead of money or sweets. In broken English, one of the Bedouins asked if we needed help. No, we’d be fine, we answered. The wind teased the fringes of the man’s black and white tribal scarf. I stood in the awkward gap after his offer and our “no,” then took a step forward and handed him the pencils. “For your children.” He swooped low from his seat on the camel’s hump, his hand touching mine.

I wanted to stop time at that touch: me in this frame of Bedouins, the desert gypsies whose heads were swathed in bold scarves, the camels with haughty faces and strong smells. But the bus driver had said, “Time to go.” Reluctantly, we said, “Shukran,” and “Ma’assalama,” and climbed back on the bus to drive off in a black belch of exhaust to the shores of the Red Sea, the Gulf of Aquba our front door.

The next morning, the gigantic sun rising red on the water, the women decided they needed to blend into this exotic setting somehow. Because I’d studied Middle Eastern dance and had mentioned the joy of moving like a W-O-M-A-N rather than a reluctant maiden, they asked if I’d teach them a dancing lesson, these six women-of-all-sizes. Of course. What else did we have to do in the hours stretching before us? After passing out a paltry collection of scarves gathered from everyone’s private stash, we all stood shoeless in the sand where I demonstrated how they could make a figure eight with their hips, snake their arms, and twirl the scarves in the stiff sea breeze.

“Let your scarf be your guide,” I shouted into the wind. “Follow it. Over your head, behind you, to the side of you. Forget who you think you are. Forget about Me, Me, Me. Surrender to the exotic, to the beautiful, to the unconscious.” And for a moment, everyone danced—children opening their arms to falling stars.

When we stopped to catch our collective breath, the consensus was definite. Yes, we needed to perform for our partners tonight. Yes and yes, those we all loved should see the sylphs of the Nile gliding through the sand by the Red Sea. In preparation, we asked our guides to take us to the bazaar where we could buy jingling coin belts, necklaces, finger cymbals, and, of course, more and more gauzy scarves.

The high anticipation of our performance that night was made complete when we noticed two of our Muslim guides peeking through the splits of palm fronds. But the appearance of the Touring Seductresses of the Sinai was short and sweet. We made a dramatic entrance to the accompaniment of a tinny tape on someone’s boom box, clanking our cheap finger cymbals that weren’t well enough made to ring clearly. We didn’t care about perfection, but we did care about something we suspected was possible. In unison, we began with the step/thrust-hip move we’d practiced that carried us across to “center stage.” Then, each woman took her turn soloing with her scarf, turning on the sand, and stretching her arms and herself toward the night sky. The scarves were magic—the way they made willows out of the women who’d been sitting on a tour bus for too long. The transformation almost happened. We almost made it to something worthy of diva status. But the fifth woman to take her solo—a woman who struggled with her considerable weight—lost confidence in both herself and the dance. She stopped. She dropped one end of her scarf into the sand. We coaxed her to continue. She wrapped her hand in one turn of the other end of the scarf, then she giggled. All six of us dissolved into laughter with her. The spell of the dance evaporated. Poof. But laughter had its magic, too.

Afterwards, everyone was in a glorious party mood. We strolled the beach where light from a crescent moon striped the water and a velvet breeze caressed our skin. Each couple slowly returned to their cabanas in the settling darkness. As David and I walked through our open door, however, the interior space felt sterile after the silky night and the laughter. Silence opened its mouth. We’d been trying too hard to solve our differences, both at home and here in Egypt. Trying to renegotiate the ground rules of marriage, neither side giving ground, we’d lost our way. It seemed that we’d worn each other out after thirty years of marriage and that there was nothing more to say. If only I could have revived the seductress in me and spun a thousand-and-one-nights story to leave him wanting more; if only he could have turned to me and said, “My beloved, you are the Only One for me. There is no other.” On that exotic night, we opted for the sound of the ocean lapping at the shore, and the sight of slanted moonlight on the cement floor.

Where was the mystery of the dance now? The mystery of the dissolving self, that sacred place where petty arguments and obsession with other options were nothing. Why couldn’t we reach across our differences and melt into our dance? Instead, beneath our courteous surfaces, we both clung to our stubbornness, recalcitrance, petulance, “It’s my way or the highway”-ness.

Now, as we sit on cushions in a circle in a Bedouin’s tent in Jordan, I watch the man who has cleared plates tuning his bulbous-backed oud and another one warming the reed on his nay. I feel my blood rising in anticipation of music, sweet music, and maybe dancing.

And then there is music. It sounds much like the recordings my teacher had used in Middle Eastern dance classes. Surprise. Out of the blue, it seems, a thin, high-heeled woman wearing a pink linen pantsuit, a gauzy scarf wrapped around her hips, a dangling necklace of metal beads, and an exotic jingling bracelet to match, a woman not traveling with our group, steps into the center of the temporary dance floor and begins to move in the style of the belly dance. To my eye, she knows almost nothing about the dance, maybe one brief lesson in a bar one night, if that, but she’s definitely making the most of her daring. Though she’s flirtatious enough and the object of much attention, there’s no roundness to the undulation of her hips and stomach, no soul to her dance. She doesn’t understand about giving herself to the music. Seduction without the seduction.

It could be a competitive urge, but I think it’s more about my need to say, “Wait, this isn’t what dancing is all about.” I stand up to join her. David watches me rise to my feet. “Go for it,” he says. He claps his hands in time to the music. “Oompah,” our tour director Shirley says, clapping her hands. “Yes. Oompah!” She’s the one who arranged this evening in the Bedouin tent where we’ve broken bread with these men in scarves and robes, our tour group sitting cross-legged, eating hummus, pita, and skewered lamb with another small tour group from England.

I borrow the scarf hanging around David’s neck—the black and white tribal scarf I bought for him at the market near the Red Sea, the one usually worn with a black cord for keeping. Goddess in pink, move over. Twirling the scarf over my head and behind my hips, I commandeer a major portion of the space provided for dancing. Maybe I’m pushy, rude, and self-obsessed, but I’ve heard the call of the dance. I lose awareness of the woman in the pink pantsuit and everything else, then suddenly, I see that “Omar” is swaying with me, his fingers clapping the palm of his left hand, his sinuous torso reminiscent of carved sand dunes changing shape. I toss the scarf back to David who watches with curiosity.

Omar and I circle each other: boy meets girl, boy circles girl, girl weaves the web as her arms snake through the air. Surprisingly, I feel shy as a country girl fresh from milking a cow—something rural in my ancestral memory carrying me back to the condition of bashfulness. But his eyes don’t leave my face. They instruct me to stay. To be here. Now. This dance is beginning to feel intimate, as though it shouldn’t be watched. But gradually, I raise my eyes to his and meet his gaze which isn’t frightening or boorish but rather direct and unflinching. I can almost feel the back of a fingernail brushing slowly across my cheek.

Maybe, because of his unexpected tenderness, I stay with his gaze. As we dance, our feet became unnecessary. I hear the beat of the hand drum and the exotic melody on the oud—someone making love to the strings. This is not child’s play. This is not the awkward teenager with slumped shoulders hiding her new height, being pushed to the center of the living room floor at a family gathering to demonstrate the latest move from her ballet lesson. This is not the one who laughs nervously, then rushes to sit back down on the sofa between the safe shoulders of her brother and sisters.

This is a call to The Dance. It’s a call to be still inside, to be calm, and to listen to every sound outside of the self. There’s no room for the self here. My body is fluid, all parts working together, and our eyes become something besides eyes, something unsolid, more like slow lava rolling over the lip of a volcano. The pounding of the drum inserts itself with a 7/8 beat that mesmerizes in the way only a 7/8 beat can mesmerize, something so foreign to our multiples-of-two or 3/4 rhythms in the West. The dancing. The drum. The plucked strings expand the sides of the tent until the night comes in to dance with us, its stars slipping beneath the flaps.

Maybe that’s how it was in The Beginning when atoms whirled to spark life into being: the creative magnet exerting its force, the female responding. And for a moment, God isn’t up in the sky. He isn’t sitting on a throne in a faraway heaven. He’s here, looking into my eyes, assuring me of the glory of being a female, the one who brings form to God’s ideas. So many times I’ve hidden in that place where I can’t show myself—a snail so bare and squishable outside its shell. But this night, this Bedouin, this man who’s one sliver of God as I’m one sliver of God, speaks silently that there is nothing beyond, outside, or above this moment. No you. No me. Only the now. Maybe we are making powerful love with each other, even though our fingers don’t intertwine, our hands touch only air, the space between us remains open and yet filled at the same time.

Early in my study of Tai Chi, an ancient Chinese discipline of meditative movement, I watch and imitate the form as demonstrated by the teacher a thousand times at least. Having learned a lifetime of dance routines, after all, I imitate what I think is being shown: another dance. But one afternoon, after seeing these moves again and again, I suddenly understand I’ve never seen them at all. I’ve been watching the external movement of the teacher’s arms—the positions, the choreography, the curl of the palm of her hand and fingers. What I haven’t seen is how she works from the center of her body, her chi, her life force, her particular vitality.

* * * * *

After the break-up of both my first marriage and a five-year rebound/dead-end romance, I make yeoman efforts to get back on track again. But, like glue on paper, vestiges of sadness still cling to me. When my friend, Joy, invites me to travel with some Park City, Utah, women to Peru for a visit with a shaman, she also invites me to join her and her husband Miles afterward in Ecuador with another group called Eco-Trek. Thus begins my six week journey to Peru, Bolivia, and Ecuador, undertaken not only for the purpose of meeting with shamans from the indigenous tribes of the Andes and of being taught by their 5,000 year old ancient wisdom, but with the subliminal hope of receiving a healing. Maybe shamans can heal me.

After spending a week with a remarkable shaman in Cusco, everything is anti-climactic when I join up with the Eco-Trek group in Quito. As our eight-person group drives up and down dusty roads between the capital city and Otavalo to meet with various shamans, I feel lukewarm about the perfumeros, paleros, and the tabaqueros we visit. I don’t feel connected in the dark rooms where they preside over tables (looking suspiciously like borrowed school desks covered with sacred implements and lighted candles) and wear headdresses of upright parrot feathers. Feeling more like a curious tourist adding notches to her exotic-travel belt, I half-heartedly participate in a group healing one night where all eight of us stand naked in a darkened room on the bottom level of the shaman’s house (situated next to a room where cattle are kept for the night). Using their mouths, the perfumeros spray each of us with flower water. This healing feels more like a dimly-lit, murky, dankest-dungeon dream where nothing emerges into clarity. What am I doing here, sniffing cattle dung and being sprayed with scented water from someone’s mouth? Why are we submitting ourselves to strange healers who don’t know any of us from Adam and whose bankroll will be substantially fatter when we leave? Do I have a center of myself which is mine alone and which recognizes a boundary?

Things change, however, when we drive to Quilajalo the next morning. In broad daylight, I shake hands with Alberto Taxo, a shaman living with his wife Elba at a retreat nestled in a valley surrounded by the Imbabura, Mojanda, and Cotacachi mountains. First I see a man dressed in an open-collared, pale blue, long-sleeved shirt, and a turquoise blue pair of cloth pants, no shoes. His long, graying hair is fastened in a pony tail with a hand-woven tie. He has a six-inch mostly white beard and clear blue eyes. I’m reminded of Sunday School paintings of Jesus. Even though sunlight flits through the overhead leaves and casts moving pictures on our faces, light radiates directly from his.

“If you wish to have a healing,” he announces, “please wait in the communal room.” He points to a tall building—a thatched-roof lodge built of thin branches and spindly trunks of trees bound together with hemp rope. The others wait outside—having had their fill of healings for the time being. Five of us file in, remove our shoes, and find a seat on the concrete rim circumscribing the hard-earth-floor-in-the-round, fire pit in the middle. Waiting for Alberto, I pray to whatever God will listen that my sadness will lift. Visualizing, as someone has suggested, I gather my sadness into an imaginary burlap bag with a Spanish label and toss it into the fire with the hope it will be purified. I’ve spent enough time with painful teachers. Bastante.

When Alberto appears near the fire burning in the pit, three large feathers in hand, I shift on my sitz bones, unconsciously looking for a soft spot in this concrete. Through the haze of drifting smoke, I witness the individual healings of four members of our group. I watch the long feathers in Alberto’s right hand tracing patterns in the air and the trance-like state of his face.

When it’s my turn to stand by the fire, Alberto looks at the whole of and the extension of me. We don’t speak. Using his large condor feathers and carefully chosen herbs and incense, he begins a ritualized healing, the same as he’s done with the others, circling and humming at random. Then, he stops. He looks at me more carefully. He squints his eyes.

Setting aside the large feathers on a table made from the sawed-off stump of a tree, he moves directly in front of me. Out of nowhere, it seems, he gathers a handful of barely-there downy feathers similar to fluff from cottonwood trees in early summer. He closes his eyes. He raises his head, chin up. While I stand there in hiking pants, yellow T-shirt, and feet free of hiking socks and boots, he circles one hand in front of my heart. I feel exposed in a way I hadn’t been when I’d stood naked in the dimly-lit room the night before. My toes dig into the hardpack to preserve my posture, my dignity, my mask hiding my frailty.

A cloud uncovers the sun’s face above the spacious room, floats past it, away from it. My eyes lift to catch pieces of light piercing the high ceiling of woven grasses, then squeeze shut as, suddenly, I feel an intense pressure against my chest. The bottled-up sadness trapped inside pushes against my skin and toward the open air where it can run free in every direction. I feel scared. This pressure might swamp my heart. But, then, suddenly, it evaporates, poof—a bubble on the surface of a mud pond. I feel boneless. A rag doll.

chi in place of the stagnant water that has been standing too long. Alberto tosses the baby feathers into the fire, nods to me, and walks toward the open door of the lodge into the day. Except I can’t remember him passing through—this man of breath and Spirit. It’s as if he evaporates into thin air.

* * * * *

The noisy, single-engine plane noses through a barricade of clouds. Bold slashes of blue attempt a takeover of the thick, gauzy skies, but the grayness is winning.

“Mira,”

Un volcán.”Christine, our group leader who sits in the co-pilot’s seat, translates. All eight members of the Eco-Trek tour group strain forward to catch sight of something in our wildest imaginations we never thought we’d see: massive, roily, dust-filled clouds of darkest gray belching out of the earth’s interior; molten magma embellished with lines of fire oozing over the volcano’s lip. But then, too quickly, it fades in the distance behind us, and the pilot points the plane’s nose downward toward the Miazal Jungle in Ecuador’s Oriente. We sink into a sea of even darker gray clouds, drop into a clearing, skid onto an underwater field-of-grass, and plow through mud. Christine pulls a battered rubber sack toward her, then opens it to a disheveled assortment of black, knee-high, rubber boots.

“Always wear these,” she instructs, sorting them into pairs, handing them out.

Most of our feet slip around in the boots, one size too big, but who’s going to complain when we’re about to cross a terrain with who knows what creatures we might surprise?

“Members of the tribe are here to take you to the village,” she says. “The Shuar were a head-hunting tribe until about thirty years ago, but there’s nothing to worry about. I’ve been coming here for a few years now, and I still have mine.” She smiles a mock-satisfied smile. “But remember. They’re a proud people. It’s an honor for you to be here. Show your utmost respect. I can bring you here because they trust me.”

Recalling scalps from Old West movies, my memory sifts through horrific images of shrunken heads—scalps hanging on a branch on a tree next to a tribal village. Fires. Smoke. Frenzied drums.

“Things have changed,” she says. I laugh nervously to myself, wondering if the medical student next to me is taking silent measure of his neck, too.

“One more thing,” Christine adds. “Women, don’t look directly into the eyes of the men as they’ll mistake that for an invitation to go with them into the jungle for big passion.”

“Big passion!” The five women in the group arch their eyebrows at each other. The men cover their smiles. Big passion on the floor of the jungle in the company of ants and tarantulas?

When we climb down the airplane stairs to greet the tribesmen who are approximately 2/3, if not half, our size, and who crowd around us, these thin, small-boned men, wave their hands and shouting in a language I can’t understand as the tropical foliage creeps toward the airstrip. Tarzan. Swinging vines. Question-mark snakes wrapped around tree branches. Nevertheless, we follow them at a quick clip on grass-covered paths, across a line of cutter ants, into dugout canoes, across two swollen rivers, through thick sawgrasses, until we reach a clearing with a compound—a lodge built of thin branches with a precisely-woven palm leaf roof. The natives show us to our rooms with cement floors, well-brushed corners, and the smell of fumigants keeping insects at bay.

The healing I received from Alberto Taxo is alive in me still. Some unyielding place in myself—some useless fortress wall—has crumbled. And so, after we settle into our rooms, four of us hiking on a well-worn path through the jungle that feels like a sauna and arriving at a clear, shallow, broad river, I can’t help myself.

“Are there any piranha in here?” I ask Christine on a sudden whim.

“No.” She eyes me suspiciously. “Why do you want to know?”

Feeling impulsive, I flop back into the clear water to let the slow current carry me. I’ve always felt at home in this element after taking Red Cross swimming lessons in Lake Mead as a child. A tadpole. A frog. A creature of water. Maybe I want to be re-baptized, to immerse myself from head to toe, to be cleansed by water and celebrate the way I’ve been feeling since Quilajalo.

Through the drops of splashing water, however, Christine looks at me with ill-masked horror on her face. She dives in beside me. Suddenly, remembering she’s responsible for any breaking of the tribal code and that maybe I’ve done just that, I think of stopping time and reversing the action. But we are both in the flow of water, floating next to each other, the sound of running water in our ears. Soon we arrive at a widening of the river, a sandy bank, and the shores of the compound. After searching the bottom of the river with our feet to find a secure place to stand, we both shake off water and push wet hair out of our eyes. Gratefully, she’s kind enough not to berate me in front of the two Shuar staring at us curiously from the edge of the river. Anything could have happened, her effort at silence says. You need to respect where we are. I cringe at the thought of my foolish insensitivity, not only to jungle etiquette, but to the natural elements.

That night, my first gaffe behind me, the eight of us are treated to a traditional dinner at rough-hewn picnic tables set on a cement slab. After dinner, more members of the tribe join the dinner staff to demonstrate the old ways of the Shuar people. “Some of these practices are still continued today,” Christine explains, “though mainly by those wishing to preserve tradition.”

Dressed in wrap-around cloth rather than the bare-breasted jungle wear often seen in National Geographic, the members of the tribe portray how they used to greet each other with a complex choreography of spears and how they entered each others’ homes to drink a brew called chicha. “This is made by the Shuar women from manioc root and saliva, which they spit into the mixture and allow to ferment,” Christine continues. “Chicha was carried with them whenever they went for a visit. And still is.”

Before we are sufficiently prepared to think up a gracious way to decline, two of the women approach our table with half coconut shells full of chicha in hand. Saliva. Fermented saliva. Save me, somebody. Their faces suggest they’re fully expecting our pleasure at sharing a drop of their strange brew. In their honor, members of our tour group pass the shell around and partake of this sour concoction with subtly pinched nostrils.

After the chicha, gratefully, two musicians appear with a guitar and a reed flute. They play music from the Andes (the jungle being an extension of the Andes, Christine tells us). Several of the Shuar men walk up to the women in the group and ask them to dance. When a rather minuscule, older man with bones more appropriate for a bird, approaches me, I remember the caution about eye contact. In the light of four inadequate floodlights shining from each corner of the dance floor, I concentrate on his feet while moving my own, and spend much of our dance together laughing internally about how this protective measure defeats the purpose of dancing. When he asks me to dance again, I can’t deal with counting his toes anymore. Impulsively, I reach across to him with my palms up and gesture for him to clap them. It’s a game I used to play with my sons: 4/4 rhythm, clap your knees, clap your own hands, then trade claps with your partner. At first he’s confused, but after a few more demonstrations, he finally claps my hand back. Then the other. Both of us laugh and hop around in a circle. Except, maybe I’m being a disrespectful tourist by playing loose with the natives. I don’t know all the rules here, except I don’t look into his eyes.

When the party has been cleared away and the Shuar disappear, Christine stops me with an amused expression on her face. “Do you know who you were dancing with?”

“No,” I say, raising my innocent eyebrows.

“That was Whonk. He’s the most powerful shaman in the Shuar tribe.”

“Oh.” I panic. “Really?”

“Really.” She smiles and turns to go to bed, leaving me there to stew in my mental juices. The most powerful shaman? Have I done something irreparably wrong by touching the hands of the shaman? If only I’d known. Maybe I should have been more careful. But maybe, intimidated by his title, position, and power, I’d have kowtowed or bowed, or worse yet, avoided him. What does it mean to be a shaman? Is he sacred? Untouchable?

As I pull down the sheets of my bed and search for insect invaders with my flashlight, I think about the word “sacred.” What does that mean to me? Respect? Awe? Veneration inspired by authority? Is sacred always something external to me—a higher being out there somewhere, a holier place than the one where I’m standing, an intermediary between myself and God? It’s good to be with these shamans. Good to drink chicha even if it is fermented saliva. It’s good to dance with the most powerful shaman. It’s also good I didn’t know Whonk’s position. I’d have worried, always concerned with the sacred code of The Other. But, respect aside, what are the things that matter to me and my integrity? I’m only trying to make meaningful contact with strangers.

The next morning, I see Whonk speaking to our translator. In the daylight, I view him with greater clarity. He seems less old, more agile, his skin more honeyed-chestnut brown. I can see strength in this man with small bones, a different kind of strength, a vitality I hadn’t been able to discern in the dim light on the dance floor. He’s no longer a tiny man, delicate as a bird, but powerful in his serenity, with his chi, with his at-homeness in the world.

“Please tell him he’s a good dancer,” I speak up, emboldened by the beauty of the day. “I enjoyed dancing with him, but tell him I apologize if I seemed disrespectful.”

The translator laughs a belly laugh at what seems to be a mammoth joke. “He was just telling me what a good dancer you are. What a good time he had.”

I look at Whonk, even at his eyes that wrinkle into a smile on his sun-worn face, two missing teeth suddenly evident. I smile my orthodontically-corrected, American materialist smile, but at this point, I’m okay with the way my culture has mandated straight teeth. I’m okay with my place in the cosmic order. He and I clap our hands together one last time and laugh as that’s the best language we can speak. This is my most important healing: to have connected to a holy man, not as an acolyte on bended knee in the presence of a sacred totem, but as a partner in the dance.

When I attend Whonk’s ceremony that night, I decide, for the first time during my six-week trip of visiting shamans, not to participate directly in yet another ceremony for healing. I’m not a woman trying to right herself with the world anymore. In the candlelight in the dark of the Miazal Jungle watching other members of my group participate in the last ritual before we leave The Land of the Condor, I know the whole earth is a holy place, maybe know this for the first time even though I’ve heard it said a thousand times. On this night, listening to the sound of Whonk’s chanting, I feel “sacred” at the center of my being, radiating from my life force, my particular vitality. It is Spirit dancing.

—Phyllis Barber

———————————–

Phyllis Barber is the author of seven books, including Raw Edges: A Memoir (The University of Nevada Press, 2010) — a coming-of-age-in-middle-age story. An earlier memoir, How I Got Cultured, was the winner of the Associated Writing Programs Prize for Creative Nonfiction in 1991 as well as the Association for Mormon Letters Award in Autobiography in 1993, and earned her an appearance on the NBC-Today Show in 1997. She has been anthologized extensively, the most recent occasion being Dispensation: Latter-day Fiction (Zarahemla Books, Provo, Utah, 2010). She has published in many literary journals, including Agni Magazine, Kenyon Review, Missouri Review, Crazyhorse, North American Review, Dialogue, and Sunstone, among others, and is one of the founders of the Writers at Work Conference in Utah. She lives in Denver.

1.