Read this as a lament, a keen. It was written, to start with, for Numéro Cinq’s series of “Childhood” essays. But this is no island idyll. It’s not even poignant; that’s too mild a word. It is sad beyond sad. It is a trip to the heart of darkness. It is also beautiful and rich and generous to that which deserves generosity. In places it makes for nearly unbearable reading. And yet it demands to be read. Years ago, I took a chance on an unknown writer and included one of Kim’s stories in the annual anthology Best Canadian Stories which I edited at the time. In the intervening years she has proved out my intuition, growing deeper, more complex, more heartbreakingly open.

Kim lives in Saskatoon, Saskatchewan (she chronicled her move there from Toronto for NC with two lovely “What it’s like living here” pieces). She is a writer and artist who grew up in Bermuda and earned an MFA in Writing from Vermont College of Fine Arts. Her watercolours have been exhibited in galleries, and her writing has appeared in Best Canadian Stories, The New Quarterly, Room, Event, upstreet and other journals. She recently completed a memoir, The Girl in the Blue Leotard. She is a Founding Member and Editor of Red Claw Press and leads an annual retreat to Bermuda for writers and artists.

dg

.

I was born and grew up in Bermuda where my father was born and grew up, and a few generations of Aubreys before him. Photos show me as a baby, sitting in a laundry basket full of oranges, fruit as bright, round and juicy as the world must have seemed back then.

Next to the plump oranges, I looked pale and thin. My parents worried I wasn’t gaining enough weight. My father bought me goat’s milk and fussed over me, helping me to sleep by bouncing me in his arms every evening when he returned home from selling jewellery in his shop on Queen Street.

Kim in the orange grove

As a toddler, I was so slight that my mother had to cross the straps of my overalls twice—first on my back, then across my chest. When a big wind rushed in from the Atlantic, she held onto me so I wouldn’t blow away. I loved how the wind pushed against my face, pressing my mouth open, promising to take me someplace new. But I loved the island too—the oranges dangling from their leafy ceiling, the crabgrass tickling my feet, the warm Bermuda earth, red-orange with iron.

When I was six or seven, my parents rented “Rocky Ridge,” a blue bungalow on a cliff overlooking Harrington Sound, where my mother taught me and my brothers, E.R. and Mark, how to swim. We’d run across our backyard to the grey limestone steps, which led down to the sea through a hollowed-out cave, its sandy walls the colour of cream. We’d rub our fingers against the crumbling limestone, stare at the small holes that seemed drilled into it, looking for the creatures that had burrowed there. Sunlight filtered through the cave, cast arcing shadows over its bright surface, enticing us to follow it out into a world of light and water.

Aubrey house with the orange trees

The cave opened onto a long narrow dock stretching out over the blue-green sound. If you stared down from the end of the dock, you might see bright fish or dark sea rays. If you looked out across the sound, you’d notice that it was encircled by land, sheltered, enclosed. But we seldom looked out; we ran for the steps leading down into the clear water where purple sea urchins raised their spikes from the sandy bottom, and shiny sea cucumbers lay waiting for us to squeeze the water out of them.

My mother taught my father to swim too, even though he’d spent his whole life on an island surrounded by water and she’d grown up in a small town in Maine at least an hour from the coast. She’d learned to swim in the cool waters of Great Pond where her aunt and uncle had built a log cabin, while my father had avoided the beach, afraid of the bullying surf that could send you sprawling under, push water up your nose and salt into your eyes.

South Shore Bermuda

The sound could be calm and glassy, or gentle waves could hold you floating. Only in a storm did the water leap up and fly against the limestone cliff, swamping the dock and filling the cave, washing away more sand from its soft walls. Sometimes, the waves would blast up over our house, and once we found a trumpet fish stranded on the driveway out front. My mother flung it over the cliff, back into the water before it could begin to stink.

Trumpet fish are long and thin. They camouflage themselves by standing on their noses amongst strands of like-coloured coral, or swimming with schools of like-coloured smaller fish on which they prey.

Sometimes, my brothers and I fished off the dock. Once I caught a squirrelfish—orange-red with a big dark eye. Squirrelfish usually hide in the reef, emerging at night, protecting themselves by raising the spines on their backs and croaking when threatened. I don’t remember if my squirrelfish made any noise. I kept it in a pail of water for a while, then dumped it back into the sea.

On Good Friday, we flew kites. My father taught us to make them out of tissue paper and oleander or fennel sticks, starting with the traditional diamond shape formed from a cross of two sticks, its flight meant to reflect Christ’s rise to heaven. We nicked slots in the ends of the sticks with a penknife, and threaded twine through the nicks, pulling it tight and knotting it, then covered this skeleton of stick and twine with different shades of tissue paper. One year, my mother could find only white paper, so to brighten my kite, I pasted on oleander petals and cherry leaves. They fell off when the wind stole the kite into the sky.

The whole island flew kites. Good Friday afternoon, the sky filled with their bright shapes and colours. Every March, a radio and TV ad campaign reminded kite flyers about the dangers of power lines, and every Easter on our way to church, my brothers and I would lean out the car windows and laugh to see all the kites stuck in the lines, or on the branches of trees.

In our backyard with its fence marking the edge of the cliff, my father would hold up the kite while I clutched its ball of twine, waiting for the wind from the sound to rustle the taut tissue paper bound within its frame of sticks and string. “Now,” he’d call, and I’d rush forward across the lawn, my kite rising into the air behind me as I hurried to let out more string, the ball of twine flipping in my hand, the kite straining against its narrow lead. Its tail, made from torn-off bits of rag my mother had knotted together, gave it ballast, weighting the kite so the wind wouldn’t toss it around and crush it. I stopped running as the wind lifted the kite higher. Its tail streamed out behind, anchoring it to the clouds.

On Guy Fawkes’ night in November, my father and his younger brothers, Dennis and Peter, set off fireworks on our back lawn near the cliff’s edge. Rockets and fountains burst and shrieked into the night sky. My brothers and I ran around in circles laughing and shouting. When our uncles lit the Catherine’s Wheel, we stopped and clung to our mother, watching the great circle of fire spin and hiss, flinging sparks into the cool damp air.

In the distance, other people’s fireworks cast brief bright shapes against the dark as we waited for Dennis to bring out the Guy. It was made from an old jacket and pants stuffed with newspaper, its head a brown paper bag, also stuffed, topped with a straw hat. I stared at its face, drawn with black marker. Its slit eyes and wide grin leered back at me like a malicious Frankenstein’s monster. I half hoped half feared the fire might spark it into life.

My father, Dennis and Peter built a small bonfire from dry sticks and crumpled paper, lit with several matches. Once the fire caught, spreading through the kindling, they mounted the Guy on top, and we watched the flames burst out from inside his dark pants and shiny jacket, consume his mean face and feed on his crackling hat. Soon the guy was one enormous flame eating away at the dark, launching flakes of ash into the sky.

One night in September, I’d learned that my mind could float free of my body, flying up like a kite or a piece of ash. My parents had gone out to dinner to celebrate my mother’s birthday, leaving my brothers and me with our teen-aged uncle, Peter. Outside, the wind tapped tree branches against the living-room window. Inside, I practiced the pliés I’d learned in ballet class that afternoon, holding my back straight, bending my knees, then rising onto my toes. The reflection of my head bobbed up and down in the darkening window. I was not yet eight and had only begun learning ballet a couple of weeks ago. E.R. was six, and Mark, who had just started nursery school, was four.

For the past year, Peter had been molesting us in the basement of his house where our parents sent us to play on Sunday afternoons, while they sat and drank tea with our grandparents. In that shadowy basement, Peter terrified and shamed us into secrecy, keeping our parents ignorant of what was happening.

If they’d told us he would be baby-sitting, I’d probably have spent the day chewing my fingernails and getting a stomachache, even though I hadn’t believed that he would hurt us in our own house. The familiar ordinariness of the wood-encased TV set, the living-room carpet we sat on to watch cartoons, the purple couch where my parents usually relaxed in the evening seemed to offer a protective spell. Besides, a summer spent visiting our New England grandparents, swimming in cool dark lakes, and picking blueberries in the woods of Maine had already begun to wash out my memories of that basement, making them less vivid, as if those things had happened to three other children.

When Peter yelled, “Stop that jumping!” and lunged after me, I froze at first, then dashed towards the hallway where the bathroom door had a lock. The TV shouted ads from its corner, the wind rattled the windows, and the walls seemed to blur as if suddenly plunged under water. Peter grabbed my arm, clamped my legs between his, pushed my face against his belly. The fibers of his shirt scratched my eyelids. I tried to scream, tried to bite him through his shirt. He gripped my mouth with one hand, forcing me to breathe through my nose, while his other hand crept up my bare leg and into the bottom of my leotard. At first, his fingers tickled, making me feel warm and shivery, then they jabbed into my flesh, sending a sharp pain up through my whole body and into my head. I tried to scream again, tried to bite his hand, but it was pressed too tightly against my mouth. My head felt light and spinny, throat dry and empty.

I learned how to run while standing still, to run until I lifted from the ground and the wind carried me up, a ballast of fear anchoring me to the ceiling. I learned how to pretend something shameful wasn’t happening, and how to clean up the evidence afterwards. Sitting in the bathtub behind a locked door, I washed streaks of blood from my thighs, learned to let the water run until all the pink had swirled away.

The next day, my brothers told my mother that Peter had shown us his penis. I told her I didn’t want him to babysit ever again. I had no words for what had happened. When we visited our grandparents, my mother and father no longer sent us to the basement to play with Peter. My brothers and I forgot what he had done to us. Memory swirled away like a pink stain in water.

Every Good Friday, we flew kites, making them as bright and beautiful as we could, multi-hued hexagons or octagons, borrowing their colours from the hibiscus, the oranges, the cherry leaves, and the clear waters of the sound. We flew kites, cheered when we managed to launch them and they didn’t get caught on a shrub, or drag our spirits to the ground. We flew kites, watching them rise unblemished into the blue, their spokes like outstretched arms, watching them shrink into distant sparks of light, longing to follow, to lift off from the red earth and climb the sky.

—Kim Aubrey

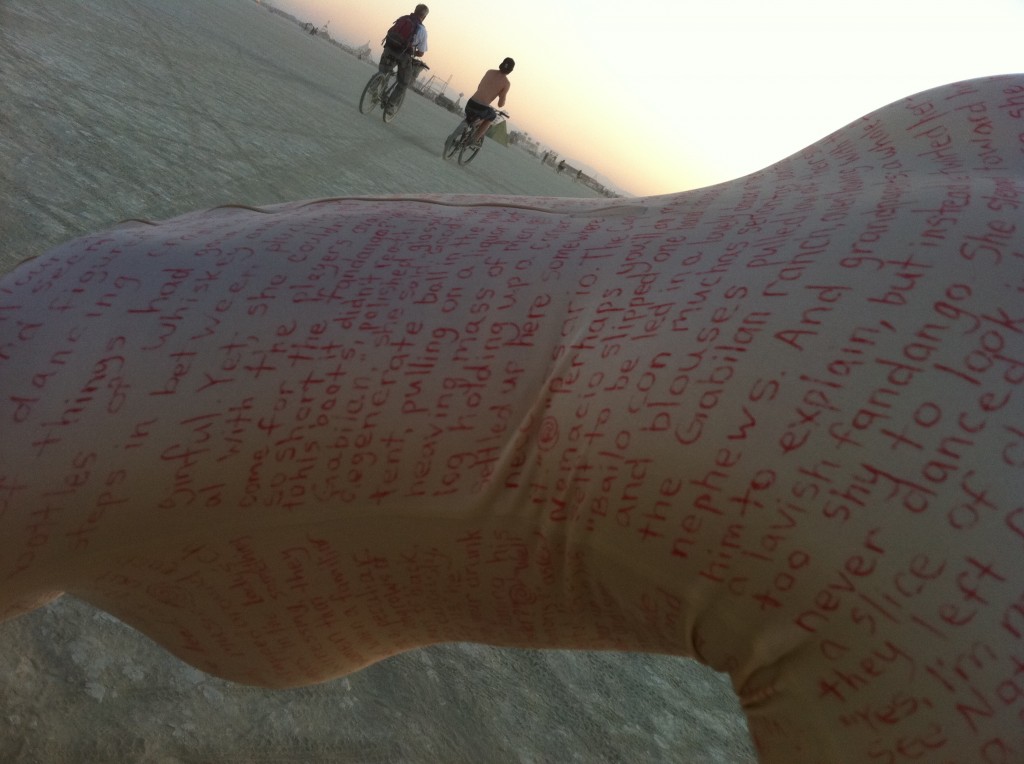

Author Wendy Voorsanger performing literary art on the playa. Photo credit: C. Voorsanger.

Author Wendy Voorsanger performing literary art on the playa. Photo credit: C. Voorsanger. Playa from a Plane. Photo Credit: C. Voorsanger

Playa from a Plane. Photo Credit: C. Voorsanger Random Trojan Horse (Exploded and burned on Friday night.)

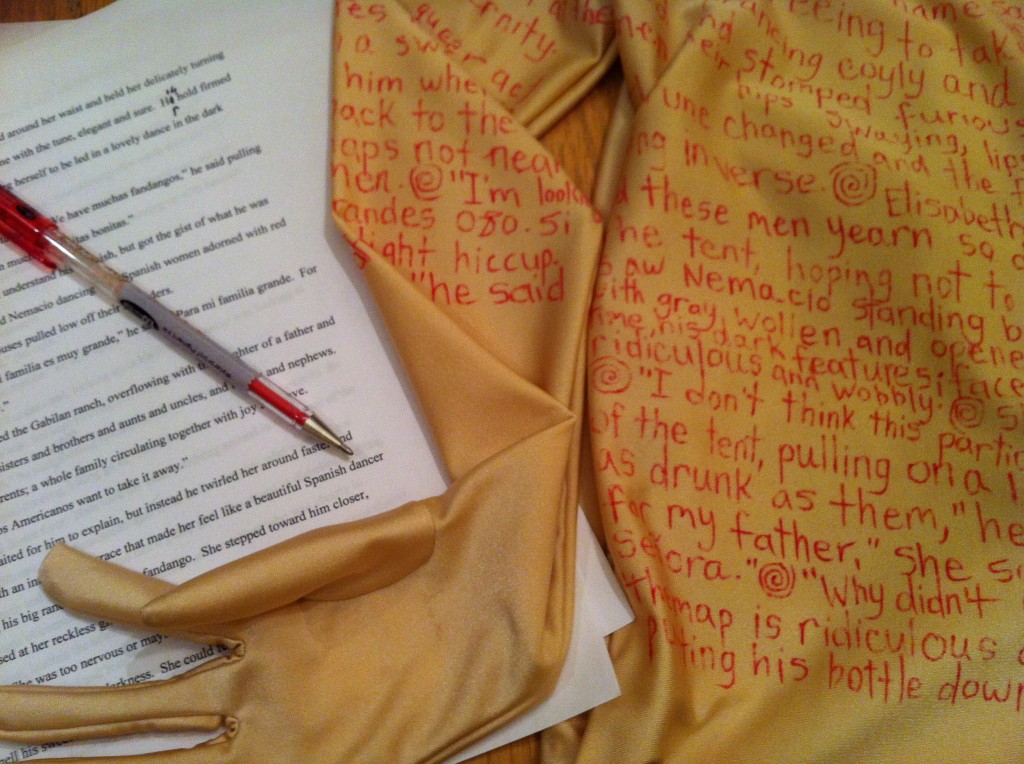

Random Trojan Horse (Exploded and burned on Friday night.) Writing novel-in-progress on Zentai Suit

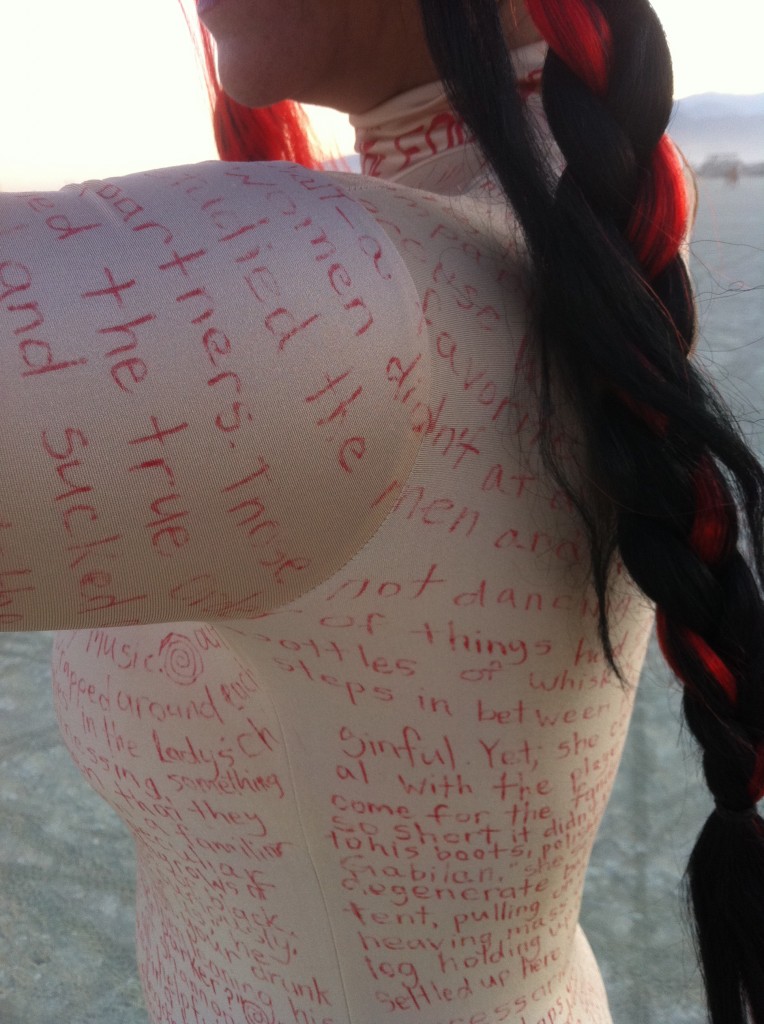

Writing novel-in-progress on Zentai Suit Wearing my words. Photo credit: C. Voorsanger.

Wearing my words. Photo credit: C. Voorsanger. Literature on the Playa. Photo credit: C. Voorsanger.

Literature on the Playa. Photo credit: C. Voorsanger.