Diane Lefer and Duc Ta (for photo details see introduction below)

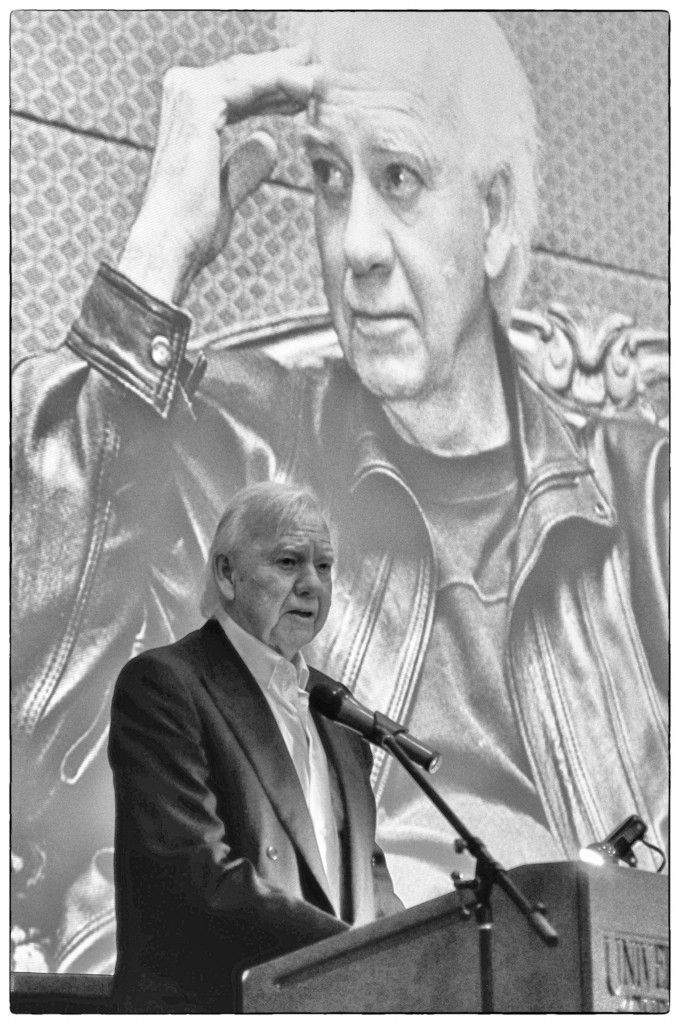

Diane Lefer is an old friend and former colleague at the Vermont College of Fine Arts. Many of you know her. She is what you want a friend and a colleague to be: forthright, hugely funny, smart and a passionate moral being. The last time we ran a workshop together in College Hall, one student called it (in her evaluation) “the Doug and Diane Show.” I do believe we had a lot of fun, and the students had fun, too (and incidentally learned something, a couple anyway). She’s a fierce and kindly person. “The Tangerine Quandary” originally appeared in the Santa Monica Review, Spring, 2010. Here is Diane’s gloss on the photo above. “In 1999, Duc Ta was arrested at age 16 when he drove the wrong kids home from school. One of them fired two shots out the window. No one was hit or injured. Duc was tried as an adult and sentenced 35-years-to-life. I’ve been advocating on his behalf ever since. We did get his sentence reduced to 11-years-to-life making him eligible for parole but he is still locked up. This picture was taken in front of the backdrop in the visiting room where you have to stand if you want a photo taken while visiting. We call it Jail Break.”

dg

The Tangerine Quandary

By Diane Lefer

Theo watched the Orthodox schoolgirls at the corner, long-sleeved shirts, skirts below the knee, high socks in the 80-degree heat, and hoped they were there for him. One reached with both hands to do something with her hair, her water bottle tucked between her thighs so it stuck out like an erection with a blue head. Then the light changed and they crossed and caught up to the girl who stood absolutely straight as she dribbled a basketball. What are they doing on a basketball court, he thought, but there they were, going to the park, and he to the bookstore, and damn but they would have made an interesting audience.

What was wrong with him that he was still too shy to approach a gaggle of teenage girls and say, “Come here. I’ve got what you’re waiting for.”

He’d come by bus and wandered a while, trying to figure out how to enter the mall itself rather than the car-park structure, then found himself on fake cobblestones, rolling his carry-on bag amid the crowds and the burbling of recycled water in the fake stone fountains, then past the multiplex theatre and the clothing stores. Pigeons huddled beside the decoy owl on the bookstore roof, unafraid, and taking advantage of its shadow.

He studied the posters in the window. So many photos, so many names, so many famous people he’d never heard of. His own claim to the Walk of Fame: a $15 bunk in the hostel on Hollywood Boulevard. Inside the store, the air conditioning hit him, less a greeting than an assault. Not as bad as the BBC interview of course, being called a bottom feeder, a canker worm and parasite. The Brits do have an abundant command of entomological and ichthyological invective. The presenter never even worked his way up to anything warmblooded. Here he finds piles of books on display, not his, more posters and book covers and faces, not his. People should have heard of—he wouldn’t presume to name himself—but they should have heard of, cared about, come out to honor her. Anne.

If people would only ask the right questions, such as: Why here, why now?

He’d answer, The Savior would have to appear among the most despised people on earth.

But she’s an American.

Precisely!

“I’m Theo Carlisle—” and the clerk looked right through him. Even Shmuley had turned himself into a celebrity now—or, depending on your point of view, an embarrassment, really, a Hasidic rebbe writing the joy of kosher sex! But if anyone should have appreciated Anne Easley, once upon a time it would have been Shmuley.

Now Barnes and Noble welcomes Theo Carlisle, Oxford University scholar and the distinguished author of Amber and Fur.

“Oh, are we starting already? Yes. Well, since there are so few—” He tells himself Salman Rushdie once read to an empty hall. Security was so tight, no one got in. Theo wonders if he actually read or spoke. To the security guards, perhaps? Here, there’s a girl, slim and dark; Mr. Gray Ponytail in a peace sign T-shirt, probably doesn’t even know it’s the symbol for phosphorus; middle-aged woman with an amber necklace, obviously has no idea what the book’s about; and the only one who looks like he’ll understand the science, probably from CalTech given the smug look on his face as he pushes his glasses back up his nose, he’ll be able to make a life in science, unlike Theo. Even the woman who introduced him has walked away. And he’s supposed to read from the book but he’s put his reading glasses somewhere and there’s something unseemly it seems to him to start patting himself, reaching into pockets. More likely it’s in one of the pouches of the carry-on. Yes, yes, he put the glasses in one pouch, the gun in the other, but he’s not sure which and mustn’t chance opening the wrong one. So:

“As the Bard—Shakespeare—tells us, There’s a special providence in the fall of a sparrow. Those words occurred to me directly I came upon a 1956 journal article by Dr. Anne Easley who was then pursuing her research at Los Alamos National Laboratory.” Without the damn glasses, he’s got to improvise. “Here was someone who was mindful of even the smallest, who found the great in the simple.” Not bad, he thinks. “She moved us closer to unlocking the secrets of the universe by rubbing glass with human hair, and rabbit fur with amber. She took us into the future by looking back to a study that was abandoned by the end of the 18th century and for her efforts, she paid a great price.”

The woman with the necklace stands and leaves. Acknowledge her departure or not? He could say We know matter is neither created nor destroyed. Therefore—if more people are being born than are dying, either people today have less matter to them, less substance, hence the shallowness of contemporary life—Then, with a chuckle he would correct himself: That’s a misapplication of science, of course. Let’s not confuse physics and metaphysics. You Americans have the notion that a Hindu or Buddhist has an intuitive understanding of particle physics. Trust me, in India, one learns the maths.

“Yesterday, I was in Las Vegas,” he says, “a city proud of its role in the testing of nuclear weapons,” where, he might add, people think redemption happens in a pawn shop. “As though weapons of mass destruction give the place legitimacy, you see, it’s not just gambling and sin, but gravitas, a serious place—and it is serious, you know. Monumental architecture. Fascist architecture. The place frightened me, and what keeps us stuck here if not gravity? Something keeps us stuck.” For a moment, he is stuck, uncertain what to say. “Those white condominium towers going up near the Strip—they look just like the white shafts over the underground nuclear test sites. This is not what Anne Easley was about.”

What she is about, the words he wants to speak aloud, the selling point of the book though obviously it is not helping sales, the most controversial claim—somehow he can’t. If only the Orthodox schoolgirls had been there.

The peace shirt ponytail speaks: “Isn’t it possible she focused on the 18th century because she wasn’t intellectually equipped for the theoretical physics of the 20th?” The man is smirking as though thinking don’t even try to put one over on us with your posh accent. They never get it, thinks Theo. I’m not posh. I’m from New Zealand. And how is it possible to be both claustrophobic and agoraphobic at the same time, but that’s exactly how he feels, trapped underground in a high-ceilinged tunnel, no air but endless space, he’s a speck in all that tight enclosure, trapped inside walls he cannot reach in a world without end. He thinks the single atom you cannot even see contains such power. As he does. Stephen Hawking can keep his Equalizer, the computer program he uses to communicate. Theo’s gone him one better. He has the great American equalizer. Amazing what you can get in Vegas, hand over the cash, no questions asked. You do need a permit for a concealed weapon in Nevada and he’s not a resident so he probably couldn’t get one which wouldn’t be valid in California anyway, but if it’s concealed in your luggage not on your person it’s not a concealed weapon. Language lies.

The slim dark girl isn’t looking at him but rather at her hands folded over her purse. The world is killing all of them slowly. Climate change. Toxins. Disappointment. But now She is come. At any rate, that’s what he has written.

Earlier, on a plane being held at the gate at Logan, her seat belt fastened, carry-on stowed beneath the first class seat in front, Liza took a calming breath, then another, telling herself it was a chance to call home while cell phones and other electronic devices were permitted. “Victoria, it’s Mommy,” while the woman in the next seat seemed to be watching, judging: This mother has learned appropriate behavior but it doesn’t come from the heart. It was none of her damn business, though Mommy in such a brisk tone of voice, even to Liza’s ear, rang false. She couldn’t help it. The tone came from work, no different really from Janine next door who simpered in adult conversation after a day of teaching second grade. Liza never could bear being spoken to as if she were a child and she would like to believe that Victoria felt the same. Her daughter insisted on being called Victoria, not Vicki, though probably only because Janine’s brat had been calling her VapoRub. And I’ll have to stop calling myself Mommy, but mindful of the passenger beside her, she said, “I miss you already, sweetie,” and tried hard to simper.

I love my daughter. I love my aunt. OK, it had been seven years since her last visit but who paid for Aunt Anne’s upkeep for God’s sake! And that was uncertain now, not because of their argument, but outsourcing. Downsizing—what they now called “right sizing”—Orwell would love it. And what do you, Ms. Investment Banker, know of Orwell? I’m an educated woman! And right now she’d taken time off and the markets were doing god only knows what—“capsizing” would be the word—and Anne refused to take her own situation seriously. “Your sister is upset about the book,” Liza had warned her on the phone. “Oh, has she read it?” “She overheard people talking about it at the Symphony.” “Oh dear! Not during the Mozart, I hope!” Anne turned anything about Patrice into a joke. How on earth had they come out of the same womb? Embarrassed, Liza corrects her own thought: same home.

It’s getting hot, even a seat in first class is uncomfortable till they turn on the power and, with it, the air. At least she can remove the jacket of her St. John suit without banging her elbow into this judgmental—or so she’s judged her—woman in the next seat. She pulls, she shrugs, she hears the lining rip. Her stomach falls. She was about to phone Mother, but not now, she can’t hear that voice now, the voice of the mother who for whom any broken toy or soiled clothing stood for Liza’s fallen nature, tantamount to sin. You could disagree with Patrice—and Liza did, you didn’t have to believe what she said—and Liza didn’t, but the words still lodged inside, solid as rockhard fact. Oh, Mother! There are other ways to live. That time in Dubrovnik in 1984—apologies, Mr. Orwell! And why apologize, why is she always saying excuse me to someone, what, really has she done wrong?, there to hear the pros and cons of emerging-market currency floats. During a break, she’d walked the cliffside and was suddenly surrounded—momentarily alarmed—by what seemed a mob of young Turks. Computer science students from Istanbul, explained their professor. He spoke good English and told her he brought a group each year for an international conference that also served as a rite of passage. He led them each time to this very lookout point above the beach where they could gaze down upon the European women sunbathing nude. The boys watched the women, Liza watched them—those sweet smooth-skinned Muslim boys. Thunderstruck at their first sight of a woman’s body, all at a sweet clean distance. They stood against the sky, nothing lascivious about their posture. Stunned, in awe. Their upbringing even stricter than her own and she’d thought, What if this were the truth about the Garden of Eden? When Adam and Eve first become conscious of their bodies, instead of being ashamed, they are stunned with their own beauty. Instead of mindless enjoyment of the Garden, for the first time, they appreciate what they have. And they are not driven out by some angry god. They hurry off of their own free will, excited by the desire to see and know the whole world and protect all of Creation from harm. Oh, fuck it. Her jacket slithers. The lining bunches. The damn book has her thinking theologically. Sit still, she tells herself as she wants to squirm, to remove the jacket, straighten it out, sit still, she might as well try to hold back a sneeze. She takes a deep breath, another, counts her breaths. Aunt Anne could have saved her from this, from being the control freak’s neurotic daughter—she knows neurotic is no longer a diagnosis but so useful as an adjective. If only, in her life, someone had looked at her the way those boys looked at the women on the beach. Before Yugoslavia was torn apart by war. Before terrorists decided the lovely Turks were too secular. Before Liza met and married the man who was not in awe of her body but was, most of the time, her best friend. Now her aunt has brought trouble on them instead of solutions. My fault, Liza thinks. If only I’d been there for her she would never have been taken in by this—this—she doesn’t know what to call him. Exploiter. Charlatan. My fault, she thinks, I was taken in too.

Anne didn’t feel like getting up. Ordinarily she wouldn’t have to. The advantage of being old—not so old—and infirm—not so infirm, it comes and goes, and yesterday she was quite ambulatory. Today? Well, you never know. And she used to think MS happened only to disagreeable people.

Je suis fatiguée, she said aloud. A person gets tired doing nothing. All her fault that the world was in such disorder, her being the Savior and all and not having the energy to bother. Poor Theo. And if she wanted a cup of tea—she did—she’d have to get up and make it herself. She couldn’t abide the communal dining room. Today at least with Theo and Liza en route, she wouldn’t be bored. There might even be fireworks. Not quite Destroyer of Worlds, but still…

Of course at the moment, it was only Iraq and not the whole world we were destroying. A little more than a year of the grand experiment, to see if we could kill as many civilians as died with the bomb she had not helped to develop. Theo wrote she’d been a pacifist and she most definitely was not though she’d probably like herself better were she a good enough person to be one. At least he got the science right. Which isn’t easy.

He made you feel important, Liza accused her on the phone. No, that’s a young person’s need. He made me feel useful. There was so little pleasure left in living but she hung on. It was years since she’d had anything to contribute. It could only be greed then, plain American greed, the habit of demanding and expecting more more more.

Right now the largest possum she’s ever seen is scrambling along the wall just beyond her window. Its naked tail curls around the sickly green wrought iron that tops off the cinderblock. The advantage of a small room: you can see out the window without leaving your bed. And thank you, Mr. Possum. Today, she thinks, I don’t mind facing the wall instead of the courtyard. Something terrible has happened to the animal. It—no, he, she sees the heavy scrotum—has a bloody gouged-out area near one eye, another through the brown-gray fur at the top of its head and then she sees another on its—his, she corrects herself—flank. And the poor creature is trembling. An ugly thing really. Pink snout checking the air, naked tail curling, claws scrabbling on the wall looking like they belong on something reptilian or prehistoric, not on a creature with fur and with blood that’s all too obviously red. He sticks his head and part of his body through the fence, then changes his mind—they do have minds, they think—and slithers back to lie along the wall. A hummingbird hovers less than a foot from that snout, getting Anne’s attention but not Mr. Possum’s. At Lake Bled, with Marius—thank God Theo didn’t include Marius in the book, at Lake Bled as they took coffee on the balcony, she’d watched the hummingbirds dance among the geraniums. Marius laughed at her—large brown moths, not hummingbirds at all. There are no hummingbirds here and she lost that much respect for Europe—old Europe, as Bush would say—how can you love a continent that has no hummingbirds? “Do you object to being called possum?” she asks the creature. Oh, the dining hall. If she ate there, Meriah, the know-it-all would correct her: opossum. We who’ve lost control of our lives need to impose our will somehow, Anne thinks, but I’ve had enough of that to last a lifetime. And Liza, little Liza, coming to visit at last. On the phone, a mosquito hum of complaint vibrated beneath her words, here’s hoping she hasn’t taken after her mother. “Mr. Possum,” she asks, “are you in pain?” Does he even know he’s injured? The shaking might be a mere physiological response. I love you, ugly creature, and the stoicism of animals. In New Mexico there were prairie dogs and coyotes, but they never came right up to her doorstep like the magpies and the skunks. Out alone one night, she lay down on the breathing earth and lay so still, a marmot crept up and lay upon her breast. A marmot, mind you, hardly a totem or a power animal. Theo has brought back her past. The three-legged cat she once had, rescued after he’d been hit by a car and the shattered limb amputated, who stayed jaunty and alert and ran as fast on three legs as some on four. He jumped and hunted and seemed oblivious to the fact that in human terms he was disabled. This possum is surely the largest she’s ever seen. “Why, you look like an alligator,” she says. Dipped in glue and covered with mousy fur.

There was a time when finding a bird’s nest could take her breath away. The thrill of finding a sky-blue egg. But the child’s wonder was destructive, wanting to possess, which usually led to taking apart, smashing, crushing, opening, killing something in order to know it. Maybe that’s why scientists make their greatest discoveries when young. Even if things had been different, my best years were probably behind me, she thinks. The young. They haven’t yet developed the ethical sense, the reverence for life. If adults could only keep the child’s eyes, she thinks, but restrain the wicked hands.

The possum’s head disappears on the other side of the wall, the fat body follows, the tail, curled for one moment more around the wrought iron is the last to be seen. All that is solid melts into air. Some know-it-all she’d turned out to be, losing her security clearance for those seven words. Former colleagues afraid to be seen with her, not even returning her calls. Somehow Theo got wind of none of it.

Over the years, from time to time, there would be one of those feature articles or books, even a panel by the American Association of University Women—they, at least, should have remembered her, celebrating overlooked women of science and so many times she’d let herself think well, maybe—and she’d scan the list thinking she might be included. Nothing. Then Theo appeared.

Time to get up. Out of bed, old girl, she tells herself and laughs. She is risen!

Theo watches a very dark black man in an orange vest hoeing some mixture of asphalt and tar into a crevice in the roadway—a very useful job but how often does anyone acknowledge him? Theo says, “Thank you,” and the man looks up, surprised.

“Wouldn’t want you to trip and fall,” he says, and on the sidewalk the homeless woman with at least a dozen plastic roses blooming from her cart mutters, “He’s happy today. Look at him smiling, pleased with himself.” The workman, Theo wonders, or me?

He crosses to the park. Boys have claimed the basketball court, the Orthodox girls are nowhere to be seen. Theo scans the ground, because he remembers being three or four and how he’d found and picked up a smooth capsule-like object, a small round white thing. It was like a tiny egg with a very soft shell. It looked like a tic-tac though in those days tic-tacs perhaps did not yet exist, or at least not yet in New Zealand. The ground was littered with them. When he crushed it, the white layer broke to reveal a lively green sprout within. He’d picked up one thing after another, squeezed them between thumb and index finger, slit them open with fingernails, anxious to see if there was green inside each one. There was. He found, picked up, opened and to his great satisfaction found that green sprout again and again and then forgot all about them until one day, all grown, he remembered. Since then whenever he’s out walking, Theo looks for his little botanical tic-tacs but he’s never seen one again.

He sits on a bench, takes out his mobile, and waits for the radio interviewer to call. The BBC still rankles. On top of it all, the presenter introduced him as a “confirmed bachelor.” Eligible bachelor, if you please. He’d even harbored hope, getting out from behind the computer, he might meet someone.

Anne. He says her name aloud. Mother of the unmothered. Shelter to the dispossessed. Anne of the supernal radiance. And yet…Lie down with a dog, he thinks, get up with fleas, and he had been to bed, not literally of course, with a failure.

In the air at last Liza falls asleep. In her dream, she has her period and cannot find a bathroom. A man—sometimes Keith—reaches for her, his lips on hers, he begins to remove her clothes. Her mother interrupts before he can enter her body. She is hungry and a table is laid before her but the food snatched away before she can eat. The flight attendant wakes her, offering lunch, and Liza’s eyes fill again with tears as she says thank you.

“Are you all right?” says the woman in the seat beside her and Liza can’t make out whether she’s expressing concern or passing judgment. She reaches to her pocket for a tissue, the silk lining bunched up behind her, and hears the Velcro-rip sound of damage just made worse.

“Yes, yes, I just—”

On top of it, Liza hates to fly. Who doesn’t these days? And how can she not think of Muslim boys every time she has to board a plane? The jitters she can barely distinguish from attraction. Even Patrice, ranting as she watched the evening news had suddenly stopped, silenced, when Muammar Qaddafi appeared on-screen. Liza was so young when he was the number one enemy in the headlines. Patrice whispered, “He’s aged well.”

The woman in the next seat has a perfect manicure. French tips. So does Liza only hers are not perfect at all. She bit her fingernails as a child to keep them short for piano lessons. As an adult, she hates herself for biting not just the nails but the cuticles, too, down to the quick. It probably counts against her at work. Poor Liza, not quite put together right, and now, a laughingstock. She has always tried to do the right thing. And no one has ever looked at her like that.

Saddam wasn’t attractive, except maybe in an Anthony Quinn or Charles Bronson kind of way. And Muslims weren’t dangerous. They were innocent. Full of passion not yet expressed. They were like her and she’d thought Keith was like her too, waiting for his chance. Patrice hadn’t approved of him, but then she approved of no one. Aunt Anne always thought he seemed a bit on the pink side, “or do they say lavender these days? Not that I hold it against him.”

If he’d just come out and be gay, maybe he’d be more fun. What a pair they made, she with her chewed-up fingers, he with his shoulders slumped. They made a good living, though. No one could deny.

She asks the flight attendant for a Bloody Mary. She’ll really want a drink later, but in the assisted living, no alcohol allowed. It does seem unduly restrictive, it’s not meant to be a sober-living facility but the administration is right to be concerned what with all the medications people take. The only part that is not sensible is that Anne chooses to live in California when it’s a medical fact her symptoms worsen with the heat. Of course there’s air conditioning. And Liza does appreciate the way Los Angeles gives her someplace to look down on. Growing up in Boston, she never had the luxury of feeling superior. One looked to Europe. That summer when the little French girl came to visit? They’d had a cookout. “Is that the sauce?” Claudy asked when Liza reached for the ketchup. “Mais, non!” she’d said. How she could sit with a real French person and refer to such a plebeian concoction as sauce? Now along comes Theo thinking just because he’s been to Oxford he can take advantage. Oh, the days are past, my boy, she thinks, when an American faces Europe with humility.

But what was she, what was Keith, so afraid of? For one thing, the cold eyes at work when she raised questions about risk. Of course there were risks, that’s why there were rewards! And never say what you want, never say what you plan. If you don’t achieve it, Patrice will be there asking Why not? The assumption, always, you did something wrong. Maybe this was why people found religion a comfort. Not because you believed God loved you. With Satan, Hell, damnation, you could give the dread a name. You had rules to help you defeat it. And Theo hadn’t played by the rules. She should have hung up the phone. Instead, she’d answered his questions and he twisted her words entirely out of context. That summer in Vermont when she ran a fever and Mother put her to bed on the screen porch. The jar of dead flowers by the bedside. And when she woke, Anne was sitting beside her and the flowers all in bloom. You see, she could tell the woman sitting beside her, My mother resented Aunt Anne who never walked into the cottage without an armful of wildflowers and I’m crying because I’ve torn my jacket and because it’s easier in the long run to give my mother what she wants, always has been, and that’s why I’ve neglected my aunt. Mother stopped inviting her. She told me I bored Aunt Anne to tears, that I bothered her, kept her from her work. I knew it wasn’t true, but—

Her aunt should have been persistent. She should have reached out for me, thinks Liza, if she missed me, and she must have. I believe she did, but her aunt had no patience for sentiment. I love you, Aunt Anne, and she got in return: So you do have a heart, like an olive has a pit! When Anne’s closest friend died after what the obituary called “a long battle with cancer,” what was it she had said? I knew she was living with cancer but I didn’t know they were fighting. Her aunt was always that way: the airy unconcern, that refusal to acknowledge pain.

They land two hours behind schedule. Liza breathes, breathes again, makes the call. “Mother, I’ve just arrived. No, it doesn’t matter. We don’t see the lawyer till tomorrow.” Oh, just listen to yourself, she thought. Negativity! I could have said We are seeing the lawyer tomorrow, but with her it’s always been about don’t, can’t, no. Until now, her Yes, go see your aunt. Yes, go see my sister. All the rancor in her voice should have burned a hole right through her throat. Upset as Liza was, too, she wanted to make light: It’s a cosmic joke really, with her being an atheist. Aunt Anne with her arm full of flowers. Liza had told the writer, “I thought she’d brought them back to life.”

She flips through the book, to the pages she’d marked with sticky notes. Where was it, what that man had written about her and Aunt Anne and the resurrection of the lilies. Wildflowers, not lilies! Even the simplest facts he distorted. Instead she found, and wondered why she’d marked it:

Stephen Hawking once believed—but believes no longer—that as the universe contracted, people would grow younger. Time would reverse and all living things including us would realize the dream, disappearing back into the womb. But even Stephen Hawking can be wrong. He admits it. And so we must move forward, in stately progression, even though we now move toward the end of Time.

The sun slants through the trees dappling light on families with their picnic baskets and Theo thinks again of Shmuley, of those Sabbath dinners in Oxford, world leaders asked to share the simple meal amongst select company. Remarkable for the simplicity. Trestle tables, folding chairs, paper plates and Shmuley’s wife and the other women carrying out platters of roast chicken from the kitchen. Shmuley had a wife, put upon though she might be. Stephen Hawking who couldn’t walk or talk without the Equalizer had a wife while Theo, Theo, Theo is still alone. Still, he was invited to attend. Thrilled and honored. Not even Jewish—or anything, really, his own religious training at that time being sketchy at best—and yet he was included. Of course Shmuley was just wheeling out the Rhodes Scholars to impress Hawking, and then the other motive: You have a publishing contract? Yes, Theo did, with a NY publisher, though all costs subsidized by the 21st-Century Last Things Study Council. In those days, Shmuley’s writing circulated in newsletters and emails. Theo could not have guessed where the rebbe was headed: friends with Michael Jackson, writing a book people actually wanted to buy. Theo walks on a path beneath the magnolias. The Orthodox celebrate four New Years, he knows. Tu B’Shevat is the New Year for trees. If the year renews itself four times, what does that due to Time’s Arrow? He steps on a fallen yellow leaf expecting a satisfying crunch. It gives way, soft, as though he’s crushed a caterpillar. Shmuley wouldn’t think him worth inviting now. Theo paid his own way to New York to lunch with his editor, or rather the editor who replaced his editor. He waited at the reception area, not allowed back to her office, and he imagined word being passed down the hall—writer on board—and doors slamming closed. Dominoes falling. She picked at a salad, distracted. He, too self-conscious to eat. Well. Well. Not the right time for women in science. Feminist angle? We’ve seen too much. Yes. Well. And the religious angle. Was not what we expected. When Donna signed the contract. Donna who quit, or was let go, and went to work for Greenpeace, taking on Japanese whalers—admirable, of course—when she should have been defending him. It was Donna who suggested “Messiah” rather than “Second Coming”—more inclusive of Jewish readers. Those people, she said, buy books. No, he’d like to tell her now, they play basketball.

A pack of boys in oversize white T-shirts passes, sunglasses worn upside-down on the backs of their heads. Should he be afraid of them? He’s out of his element in this country where people lie stretched on the grass and you can’t always tell who is sunbathing and who is homeless and now a child body slams him and doesn’t even say pardon. Children run from one striped tent to another screaming Please, Mom, please! It’s a cat adoption fair and in this he sees not coincidence, but the Hand, and so he goes from tent to tent looking at torties and tabbies and calicos. Anne won’t be allowed to keep it and he certainly doesn’t want to so, inspired, he asks, “Do you have one that’s dying?” A large white man confronts him: “What are you? Some kind of Satanist?” He tries another tent and speaks to a woman who wears what appear to be rabies tags around her neck. “Have you got one that’s dying, about to be euthanized?” He ducks as her face turns so red he expects her fist. “I want to take a sweet creature no one else wants. The stone the builder rejected.” “Why?” she demands. “It’s for my aunt,” he says. “I won’t be able to take it back to New Zealand after—” He swallows hard. “—after it brightens my aunt’s last days.”

The late afternoon sun blinds Liza momentarily. She’d taken off her dark glasses when she checked in at the desk in the main house. But now she’s in the courtyard with the bees drunk on pollen and sunlight and she fumbles for the glasses as her heart speeds up a little. Aunt Anne is bound to be stubborn. She doesn’t respect me, Liza thinks, and I do still love her. You were different as a child, she’s said. Intricate. You played the piano, beautifully, with feeling. Overnight it seemed you became hardheaded and pragmatic. I discovered Ayn Rand. We all read Ayn Rand. That’s what you do when you’re young, but even then, you have to realize the only good parts are the people having sex. The prose style and the philosophy are deplorable. Deplorable. What was it with the Easleys and formal speech? We don’t talk like Americans. You spoke French, her aunt recalled. I remember you shouting out, C’est moi! Patrice taught her to say It is I. Never It’s me and how can a child go out into the world and be accepted by other children if she says It is I? Deplorable. Lamentable. Knock knock. Who’s there? C’est moi. Liza sits for a moment on a stone bench and tries to calm herself with the sound of the water plashing in the artificial pond. Yes, I enjoyed talking to him, her aunt had said. Theo speaks my language and you don’t. I could never tell anyone in the family what I was doing. You’ve never wanted to hear about my work either. You do something financial. It’s not interesting enough to understand. But Liza remembers once upon a time Aunt Anne did share her work. Subatomic particles, invisible to the naked eye. It made so much sense to a child who felt small and secret with so much going on inside her. Outwardly obedient. So much turmoil. And she imagined herself shrinking down, entering the atom, cavorting, whirling madly with the electrons.

Now she’s biting off an annoying bit of chipped and broken nail and facing the six-story building that houses the people who are not expected to ever leave their rooms on their own. Aides bring them their meals on trays. “Cell-fed,” is how Aunt Anne put it. Clinic on the ground floor. Funny how the bougainvillea has two colors on a single bush. Not so funny when she gets up, goes closer, and sees the pink turns a gingery orange as it withers. The artificial pond gives off a scummy smell. Some kind of algae or the effluvia of the carp and turtles, dozens of them, plashing and paddling, a few lying in the sun, further ornamenting the ornamental stones. Liza turns away and there’s the maze of rose bushes and bottle brush trees and jacaranda and the rows of attached one-room cottages for the ambulatory. She did a good job finding this place when it all happened so fast, Aunt Anne carried off the ship returning from Alaska, with a flare-up, an exacerbation, whatever they call it, she’d flown out at once. “You can’t live alone anymore.” In the main building, there’s the dining hall, the game room, computer room, music room. “I’m not alone,” her aunt had said. “I live with a very companionable cat.” Minou had been with her almost 17 years. Then—sad, but unavoidable. No pets allowed.

The sun reveals the dirt on the windows, like smudged fingerprints as though someone has tried to get in or, Anne thinks, this prisoner, me, was trying to claw her way out. Of course there’s the daily van for shopping—under guard—the aide who’s always alert, lifting the box of tea from her basket: Do we really want caffeine? and Anne, only occasionally defiant enough to say yes. The facility arranges excursions, hours on the bus to Vegas listening to inane chatter, Hilda in the seat beside her announcing she’d always been sickly because her nose was too big for her body. I take in so much air through my nostrils, my lungs can’t handle it. The doctors never figured it out, the word doctors said with a sneer, clearly directed at Anne. I’m not a medical doctor. I’m a Ph.D., and then of course she had to deal with that health aide, just the reverse: You claim to be a doctor but I know you’re just a Ph.D. Anyway, she’s not a gambler. Vegas. Those frightening hotels with their landscaping, flowers, tropical foliage. What poison do they use? Not a bee or bug to be seen. And stay with the group! when she wanted to tour the test site. She’s in her armchair, Theo’s book on her lap. He got the science right. Not bad for a popularizer. She thinks she couldn’t have written it. All those years teaching science at the junior college, a come-down not so much in status as in self-esteem. She was a terrible teacher. Which didn’t stop J. Edgar Hoover from investigating her course—Science and Ethics—when what the hell else can you teach girls who’ve never learned calculus? I just wasn’t any good at it, she thinks, something she has thought so many times before. But the science bits aside, Theo certainly took liberties with the truth. That one absurd sentence. Just one, but enough to make Patrice and Liza blow their gaskets. Well, why not? Her own life had changed with seven words. It took Theo—she counts them—44. It will not have escaped the reader’s notice that certain reported incidents in the life of Anne Easley strongly suggest that this humble woman, now languishing in a modest assisted living facility on the outskirts of Los Angeles, is in fact our long‑awaited Messiah. I’m not humble, she thinks, this place is hardly modest, though this room way too small for a human being with books and papers, computer, and drawers enough to hold all the damn pills. Compazine, prednisone, what else have I got in here that I avoid taking? She doesn’t dare skip the Lioresal, not with company coming and in fact she needs to get herself to the bathroom, now. Being carried off that ship! The shame of it—bladder and bowel, and the terror, her legs not working, body beyond her control. But it was the fear, not her body, that did her in. She gave up her freedom out of fear. Now she lives in a place so damn cramped, closet too small to hold the wheelchair—even folded—and the walker which thank god she rarely has to use. Fluctuations hour to hour, like the weather. Don’t even try to measure my rate of decay. Vertigo? I can take a pill or wait for it to pass. And I’m not exactly languishing. Certain reported incidents. Tony Banerji in the lab when jagged strokes of lightning cleaved the air and he saw me emanate a supernal radiance. True enough. I got him straight to the emergency room. Detached retina. So yes, I saved the sight of the about‑to‑go‑blind. My own episode of optic neuritis, she thinks, in retrospect probably the first manifestation of disease. As for the rest, she’ll have to calm Liza down. Look: it will not have escaped the reader’s notice—that’s echoes of Watson and Crick. It escaped your notice, but the whole thing is obviously a parody, a spoof. And aside from the ridiculous claim, he got almost every personal bit of it wrong. Some of which was her own fault. She flips through the pages. That bit where he has Edward Kohl saying Why would I hire a woman who won’t have sex with me? I might as well hire a man whenwhat he really said was he wouldn’t hire a woman he wasn’t interested in sleeping with. Vanity had urged her on. To avoid repeating that humiliation, she hadn’t set Theo straight. La plus ça change. In spite of the book and the bizarre claims, no one has come to her door. No phone calls, no interviews, no curiosity. No outrage, except for Patrice and Liza.

→ 2 ←

“Amber and Fur,” says Liza. “Even the title is distasteful. Vaguely S&M.” Then, when she says “Disgusting,” she knows she sounds just like her mother. What a relief the room is so cold with the A/C she can keep her jacket on. No chance the torn lining will be seen. But that shouldn’t matter here. This is Anne, not her mother. “We’re seeing the lawyer tomorrow.” She takes a sheaf of papers from her briefcase. “Letters for you to sign.”

“I’m not seeing a lawyer.” Anne thumbs through the pages. Thomas Curwen. Gina Kolata. Scientific American. The Atlantic. “You’ve left out the journals.”

“I don’t know the journals.”

“You’ll find them all around my room.” Because she kept up, exercising her mind though she hadn’t worked in years. It was her functional capacity and she had to use it, just as birds rejoiced to sing. The very first time she saw a robin pull a worm from the earth, she’d screamed with delight. There is something fulfilling when you see a creature do exactly what you’ve been prepared to know it will, by its nature, do. That might be what brought her to physics: the desire to see the invisible—the quarks and muons and all the rest—behave just as predicted. She sees Liza has left out Margaret Wertheim at the LA Weekly, not to mention K.C. Cole at the LA Times. “Do you really want me to send letters to the editor stating, Just to set the record straight, I am not God?” She says, “Liza.” And Liza’s eyes fill with tears. “This foolishness is probably the fault of the marketing department. He’s really a sweet boy.”

“But it’s—”

“It’s just a bit of nonsense. It’s not harming anyone. Not like your president who lies to get us into war. He and the Christian Right are undermining any sort of legitimate science.”

“We’re not going to talk politics!”

“Of course not,” says Anne. If her niece is an idiot, she’d rather not know it. “Don’t forget, my relapses may be brought on by stress.”

“Anyway, he’s not my president,” says Liza.

“I’m sure you voted for him.”

“No one I know has the slightest respect for him. But he’s cutting taxes and regulations so we’ll all do well. Longterm prosperity, Aunt Anne. That’s what matters.”

To have to listen to such nonsense! Anne sighs. “This is where I could use a smoke. Of course with my luck, on my way to Golgotha, a stranger will step out of the crowd and hand me a cigarette and—damn!—menthol.” Her right leg cramps up. The damn elastic stockings. She keeps asking herself why she wears them.

“What are you talking about?”

“Golgotha.” She tries massaging the leg. “Surely you’ve heard of Golgotha.”

“Are you all right?”

If I were, would I be here? “The Stations of the Cross,” says Anne. “You really don’t know? Entirely uncontaminated by religion. My sister did one thing right.” Though they both know Patrice merely found every faith she tried way too lax. Fundamentalists, Orthodox Jews, Mormons. Never enough rules for Patrice! Besides which—no god but the mother who gave you birth!

“I have some basic knowledge,” says Liza.

“It’s actually the vinegar that interests me more,” Anne says. “Christ is carrying the cross, on his way to crucifixion on Golgotha Hill. He’s thirsty, and a man gives him to drink. But it’s not water, it’s vinegar.” This is something Anne’s always wondered about. Vinegar could be a mercy, not a cruelty. Not as pleasant to drink, but it puts an end to thirst much more effectively than water. A kindness. “Be kind and turn on the radio. It’s time for Theo.”

For a moment Liza can’t move. This is worse than she’s imagined: he’s on the air.

“Please, Liza. We’re missing the start.”

—Easley overlooked because she was a woman? I suppose I identify with her situation, being a Kiwi. From New Zealand. We, of European descent, we’re called Paheka—it means Other. While the indigenous people—Maori, you see, just means normal, ordinary. The whites may be in the majority and control the money—just as women make up the majority in this country and control the household finances—but we’re still marginalized.

Isn’t that a bit like white women saying the oppression they’ve experienced is equivalent in some way to what black folks—

We don’t call the shots anywhere in the world. Unlike the Australians, New Zealand didn’t send any soldiers to Iraq, but you see my face, my skin—It’s hard to appear to be part of the most powerful class of people in the world and actually have none—power that is.

I wonder if the Maori would agree.

To be a white male without power,

—with privilege.

Yes, I suppose, yet when one doesn’t face a struggle over basic comfort and necessities, that’s when one feels the spiritual needs.

Who cares, Anne thinks, about New Zealand? Even now, in the interview about me, I’m not even mentioned.

Compare our national anthem to yours.

And Theo sings:

May all our wrongs, we pray,

Be forgiven

So that we might say long live,

Aotearoa.

Anne is moved in spite of herself. We have not done penance, she thinks. She’s never gone with head bowed to Hiroshima, not that she had any part in that, but only because she was born too late.

You’ve said she fell out of history.

Yes, and it happens more easily than you might imagine. You see, it was Anne Easley who argued that the word “force”—particle physicists then referred to the “nuclear forces”—the “weak force” and the “strong force”—Dr. Easley argued that the word didn’t accurately convey what happens on the subatomic level. When she suggested, instead, the word “interaction—

—a less macho approach. Interaction not force. So gender played a role?

Or her convictions as a pacifist.

“I was not!” says Anne.

The idea caught on during the Sixties and proved to be one of those paradigm shifts that so fruitfully opens every era of scientific progress.

Now wait a minute! I interviewed Murray Gell‑Mann not long ago—for our listeners who missed that broadcast, I’m referring to the Nobel Prize laureate, Father of the Quark—and he talked about the strong nuclear force.

“A better prepared interviewer than I would have expected,” says Anne.

Yes! That’s just the point! Advances were made and then the word “force” came back into favor. The paradigm shift yielded knowledge and then was forgotten. This is how a person’s contribution becomes invisible.

Read us a bit, will you?

Of course! I did bring my reading glasses—

Anne Easley’s downfall began with a cat and a simple attempt to amuse a little Pueblo Indian girl.

Depending on cultural perspective, Los Alamos was, in those days, the end of the earth or else its very center. Sage grew low over light brown curves of landscape like body hair of the earth—

“Oh, please!” says Liza.

—and just like a body, in the intoxication brought on by desert air, the earth seemed to breathe and to sigh. At night and in the cooler afternoons, the scent of piñon smoke brought tingles to the soul. All around, indigenous people continued with their ancient rites as scientists pushed the boundaries of Man’s future.

“I think he’d sell more books if he didn’t read from it,” says Anne.

In the United States, the suppression of Native languages and culture were a part of the genocide against the First Americans. But in the magical desert of New Mexico, the drums still worked a beat beat beat to activate the white as well as Native heart. Anthropologists and artists had extolled the Pueblo way of life, and repression halted at the border of the Land of Enchantment.

Anne Easley had magic of her own.

“Abracadabra!”

In New Mexico she briefly feared she’d lost it. This was the woman a colleague in the lab had once described, as the reader will recall from a previous chapter, as emanating a “supernal radiance.” The woman who, as the reader has already seen, resurrected lilies for a sick—and soon to be healed—child.

“That’s enough!” says Liza.

But ever so fatefully, one night the Indian janitor’s young daughter peeked in Anne Easley’s window as the woman of science was sitting down to her solitary meal. Who is to say whether the little girl was frequently on the premises, or this was the first time, or whether merely the first time she ventured to the home of one of the great minds of science? The child of ancient lineage crossed paths with the woman—a relatively young woman then—and their eyes met. Dr. Easley’s mind instantly shuffled through the memory cards of her life and recalled her own niece Liza—

“I truly am sorry he included you, dear—”

—and how she used to amuse the girl—

“—since it’s so poorly written.”

—and so Dr. Easley spontaneously picked up her spoon, rubbed it with her napkin, and pressed the concave side against her nose. How many times had it transpired in the past that Dr. Easley and young Liza would let the spoons hang from their noses until Liza’s disapproving mother would enter the space—

Why did I ever agree to speak to him? thinks Liza.

—and the two miscreants would momentarily maintain composure only then bursting out into merriment and letting the spoons fall! But on that fateful evening in the Land of Enchantment, the spoon did not adhere to Dr. Easley’s nose. The little girl, seeing only a white woman with very bad table manners, walked on, unimpressed, never knowing her profound contribution to scientific thought, and Dr. Easley could only turn to her supper in silence.

Why why why did the damn spoon not stick? The problem preoccupied her highly evolved mind. Then, Eureka! A hypothesis! The desert air was just too dry. If she first breathed on the spoon, the condensation from her breath was all that was needed to make metal adhere to skin. But this was only a beginning.

And this was where it ended, thinks Anne.

Was she romantically involved with a member of the community?

Of course she was, thinks Anne. Lennon and McCartney didn’t invent sex, you know. We had Kinsey. We had Elvis, not to mention Margaret Meade.

Was that why she’d worn the amber necklace inherited from her grandmother?

Something worth mentioning to Liza: the Kinsey biography is full of distortion, too, sensationalized nonsense.

Anne Easley spent the night alone—except for her cat.

Yes, the affair was over. Damn you, Theo, why are you making me remember? Lying beside John in bed, just entered into the state of post‑coital intimacy, he whispered, “Anne, do you consider yourself Nobel Prize material?”Not that she’d never had the fantasy but—”If you’re not that good, go home and have babies. Science doesn’t need you.” Men! Only Marius had been different.

The feline lay in her lap. What thoughts, what dreams of fulfillment, what realities of frustration played through her mind and heart—at this time as human as yours or mine—as she stroked the pet? Static electricity tingled against her hand, and the amber pendant brushed against her fur and it was a thunderbolt. The triboelectric sequence!

Anne reaches for Liza’s hand to keep her from biting at her cuticles. How tell her how frustrated I am, stagnating here, when she means so well? An ordinary apartment, that’s all I want. I could manage with my Social Security and pension. Take my chances. A little more difficulty than here, a bit of risk, but the worst death is from boredom.

Since the Greeks we’ve known that when amber is rubbed with fur, the electrons go from the fur to the amber.

“But what does he mean ‘go’?” asks Liza.

Much more so with rabbit fur than cat. Rabbit’s fur, glass, quartz, wool, cat’s fur, silk, human hair, cotton, and so on, in sequence.

“But what—?”

“Shhh. Listen.”

The phenomenon functions much like a magnet but without any metal. But no one has figured out how to make it useful which, in contemporary terms means how to exploit it for profit. What after all is to be made of a piece of amber that gains the property of attracting lint? Benjamin Franklin flew his kite and frictional electricity was no longer worth the bother. The triboelectric sequence fell into the dustbin of history.

As I did, thinks Anne. But not the way he tells it. She’d believed them when they told her Marius was politically suspect, that she had to stop seeing him. Oh well, a European man, he’d cheat on her sooner or later, she’d thought, but science would always be there for her. Until she became suspect too. Maybe Marius would read the book? Maybe—but if he was still alive, he was probably driving around in a sports car with a 20-year-old. She gave him up and lost her security clearance anyway. Don’t feel sorry for yourself, Anne Easley. They persecuted the Father of the Atomic Bomb, why should they show mercy to you? She’d done nothing wrong, merely followed her thought where it led: Even Einstein’s universe was a bit of a machine whereas she’d become fascinated by unpredictable change. Made the mistake of publishing her musings, first about randomness, about causality and chance, those naive little notes about particles and her doubts.

As though he’s read her mind:

What is to be done with a particle physicist who loses her faith in particles?

And Anne remembers: All the measurements and all the theories, all based on the notion of building blocks, of elementary particles, of entities so small they were indivisible. Unfortunately, they never seem to act that way. There were smaller and smaller subparticles to be found inside them. And worse, they would decay and transform, one thing apparently becoming another. Popping in and out of existence. Every notion melting away. Nothing stable. She gave her article an epigraph: All that is solid melts into air. The words she thought were Shakespeare’s turned out to be from Karl Marx.

Dr. Easley’s work was impressive, groundbreaking without a doubt, a precursor to chaos theory—

In Christian theology, “precursor” means—something Anne will not mention to Liza.

—but that’s hardly the reason we are compelled—required—to take time away from our daily pursuits and turn our hearts and minds to Dr. Easley, or why I’ll be making a pilgrimage to her side later today.

“He’s coming here?” says Liza. “Did you know he was coming here?”

→ 3 ←

He stands sweating in the doorway with a canvas tote on his shoulder, rolling luggage at his feet, cardboard box in his arms. Outside, someone is playing music. Someone is grilling meat. Late afternoon sun shoots through the trees and Liza squints. Theo doesn’t look like a fanatic. He looks, she searches for a word—fuzzy.

So this is the niece, he thinks. Dr. Easley had warned him she’d be visiting. And she is not happy about the book. “I’m afraid I’ve brought discouraging news about the ozone layer,” he says, “but Dr. Easley—”

Anne is beaming—light. The two people she loves most. Well, she does love Liza. And perhaps she shouldn’t use the word “love” for Theo, but she does care about him. Over the last three years, there’s no one she’s talked to more.

“—you look radiant!” he says.

While Liza stands there with cold gray eyes and what is she so upset about anyway? The poor boy, Anne thinks, is just trying to get by. He was never at the top of the class, and how many jobs are there in the entire world for a particle physicist? Theo’s no genius, but he’s bright enough to be passionate in his interest. Teaching high school, even college—it’s an honorable career, but no one knows better than she herself what it means when you’re in love with science. Without colleagues—especially those more brilliant than yourself, without that sort of stimulation, being in the center of it all, a part of you dies. He’d attached himself to her to stay alive.

“—and I’ve come bearing gifts from—” A helicopter overhead drowns out Theo’s voice. He thinks he should have brought something for Liza. Not that she seems easy to win over. She should be glad the general belief in publishing is that in wartime the public needs uplift. Otherwise, they would have wanted a pathography. Instead of a redeemer, her aunt would have had to be deviant. A legitimate way to get attention—perception is all about deviation from the norm—but he would never have written anything negative about Dr. Easley.

He puts down the carton and from the tote produces a bouquet of irises.

“Oh, Theo! Thank you! The vase you brought last time is in the cabinet. There.”

“And more!” he says. A bottle of wine.

“Cabernet!”

“Alcohol is not permitted—” Liza says, but her aunt cuts her off, laughing.

“Liza, when he took me to dinner, he kept asking for Cab Sauv and the waiter kept bringing club soda.”

“And one gift more,” Theo says.

“Frankincense!” says Anne.

“Damn! I knew I’d forgotten something!“

“But you’ve brought the myrrh?”

“I would have done, had I any idea what it is.”

And I would save him, thinks Anne, had I any idea how.

Liza’s stomach churns. So it’s all a big joke to him, too. She doesn’t know which explanation she hates more: Theo’s book as mad delusion or as hoax. “You should know,” she says, though it might be better if he didn’t, “we’re seeing a lawyer tomorrow.”

“If I knew the person’s name, I’d cancel the appointment right now,” says Anne. And what would save Liza? Moving thousands of miles away from Patrice for starters. “Calm down, dear. Theo, meet Liza. She’s not always hostile and litigious. In fact, she’ll find the crackers in the cabinet and maybe even some cheese. The fridge is that box beneath the sink, looks like the mini-bar in a hotel room. The sight of it still fills me with hope, but, as you know—”

Theo makes do with what he finds—two juice glasses, one coffee mug—as he uncorks and pours the wine. Liza arranges cheese and crackers on a cutting board. Anne leans on her cane and as she feels the curved top fit her palm, she thinks of a shepherd’s crook and then—this will get Liza’s goat, or lamb—a bishop’s crozier. Ha! Or a vaudeville hook to pull someone—which one of them?—off the stage.

“And now my third gift!” she says.

“No! Not yet!” Suddenly Theo regrets all. He has no idea why he’s done what he’s done. Bringing her a dying animal, buying the gun. Impulse and yet— Hasn’t he done these things precisely because they make no sense? Thinking, he thinks, took him only so far. “Later,” he says, and unfolds the wheelchair waiting in the corner. He seats himself and likes the way it feels. He could be Stephen Hawking as he rolls himself over to retrieve his glass of wine: “To Dr. Easley.”

Anne lifts her glass and sips. Liza glares.

“Liza?” Why is she so difficult? Bob Dylan’s biographer years ago called him the Messiah, and then that Harvard professor wrote about alien abduction. No one was about tarring and feathering them. “Believe me,” he says, “I had no wish to cause you or your family any pain. Dr. Easley is brilliant. I’ve got the knack for explaining complex concepts simply. I thought together we—”

Liza’s eyebrows arch. “I didn’t find the science parts of your book all that easy to follow. Everything being one thing. Really? By the way, is it Dr. Carlisle?” she asks, knowing very well that it isn’t.

“If I were to take a movie of you running, and look at it frame by frame, suppose I label you Liza when your left foot is off the ground, but Hedgehog when it’s your right foot—” And on he goes when she only said it to jab at him, not to invite a lecture. “What about when you run past the frame and we can no longer measure you? Do you cease to exist? Isn’t it absurd to define you frame by frame, and just as absurd to identify the film with you? We can repeat over and over again that we’re merely tracking your movement, the traces you leave on—”

“I don’t get it,” Liza says.

“These concepts aren’t easy. That’s why I worked so hard on—”

“What I understand is that you misrepresented. You humiliated. You lied.”

Liza in her armor with torn lining. Theo of the pale lashes, his arms covered with a light coat of hair. Anne, glittery as an addict scheming for a fix.

“Not a lie, Liza. A model of reality.” Though models, he admits to himself, in being mere approximations are always lies. That’s the dilemma. “Just for example,” he tells her, “every child who grew up in the 50’s must have seen the Walt Disney image of atomic energy hundreds of times. All those ping pong balls—or maybe they were billiard balls—“Dr. Easley, do you remember?”

“Ping pong, I think.”

“So what?” says Liza.

“Lots of small white balls colliding and setting off a chain reaction and that picture of little colliding white balls is deeply embedded in each and every head of millions of people alive today, most of whom can’t even tell you what kind of ball let alone explain what it means. One must choose one’s metaphors and images very carefully. It’s what I call the tangerine quandary. In grade school, the teacher’s just finished telling the children the earth is round, and then you’re made to study a two‑dimensional map.”

“Maybe it’s a tangerine in New Zealand. I was taught an orange.” Liza, oppositional still. “If you take the peel from a round orange and flatten it, you’ve got the Mercator projection.”

Anne shakes her head over the things they tell children.

“Orange, yes. Orange is the standard, the original ideal image from which the tangerine is derived. But getting an orange peel off in a single piece suitable for flattening isn’t easy. If one believes the students will experiment, one might be advised to use the tangerine as the example.”

“I can peel a tangerine,” Liza says, “but I doubt I can flatten it out to look like a map.”

“Splendid observation!” Theo says. “So perhaps even when you admit the possibility of direct experience, you lead the children to frustration and failure. Perhaps it’s best to tell them the orange, and have them accept your way on faith.”

“They should use their imagination to picture the peel flattened.”

He stares at her because this, precisely, is the problem. How does one believe in a God one can’t see? Only through the imagination, but how is it possible to imagine a God who could turn his back on concentration camps. On Pol Pot. On AIDS. On war. On so much suffering. Invisibility, he thinks, equals impunity. For too long God has been afraid to show his face.

“The Mercator projection does not look like an orange peel,” Anne says. “Furthermore it distorts the globe and its proportions for all purposes except for navigation.”

“There’s the quandary,” Theo says. “How to teach, how to convince. One bends over backwards to make the truth accessible and what happens? People go bit by bit ever so much further astray.”

“Einstein did it all in his head, didn’t he?” says Liza. “Actually, I don’t think I can peel a tangerine in one piece either.”

“If I had one in the refrigerator,” says Anne, “we could be empirical about it.”

The world is not a tangerine, thinks Theo, but we reduce it to the peel of a fruit to understand it. Now it seems he’s failed, at least with Liza. And why? Because he didn’t want existence reduced. He wanted people to see it’s bigger, bigger by far. “I tried to explain our lives by making them bigger.”

“The evidence of things unseen,” says Anne. “We offer tangerines when what’s called for is faith.”

“And Liza’s upset because faith is what I offered,” says Theo. He’d invited people to try what he had done: surrender his rational mind in order to be receptive to—something. “Complementarity, Liza.”

“Another concept I did not understand.”

“Neither do most of the scientists who rely on it,” says Anne.

“Take incompatible premises,” says Theo. “No way to reconcile them.” You and I. “Science. Religion. You can fight over who’s right, and yet neither model accounts for all phenomena. So Bohr said, each is mutually exclusive, but the whole truth only exists when you accept both. What do you say to that, Liza? Brilliant? Or intellectually dishonest? Just a way to keep everyone happy?”

“Absolutely dishonest,” she says. “And your publisher knew it!”

“My publisher understood I was writing something rather like the Bible.”

He really is mad, she thinks.

“A book my sponsors could take literally while to the general public it would read as metaphor. Poetry.”

“But the Messiah!”

“It is a book about physics.”

“No, it’s about my aunt!”

“In particle physics, one refers to charm and color and up-quarks and down, but it doesn’t mean color or charm or direction. One assigns an old word to do a new job, to denote certain properties, or intimations of behavior. And I do admire Dr. Easley an awful lot,” he says.

“I’ll draft a document for you,” Liza says. “Just acknowledge what you’ve told us. You were paid to make this claim and you know it’s not true. Sign that. We’ll drop the lawsuit.”

“There will be no lawsuit!” says Anne.

Liza stares at him, trying to remember why she is angry. With righteous indignation. But what is righteous about it? Self-righteous, really. Why does Aunt Anne see it as a big joke while she experiences it all as shame?

The irises are in a vase, the vase still sitting in the kitchen sink, and Liza goes to the sink to get them. The flowers look like the open beaks of baby birds. There’s a fuzzy yellow stripe like a caterpillar asleep inside each petal. She forces herself to touch one and sees her aunt carrying wildflowers into the cottage. The anger she’s felt for days—is it really her own or is she merely casting a proxy vote for Patrice? What sort of person can’t tell whether she is feeling a feeling! Liza picks up the vase. “They’re beautiful,” she says. “Thank you.”

“I want my third gift now,” says Anne. “Whatever it is.”

It’s a mistake, thinks Theo, but he carries the carton to her and from it lifts the gift. Anne looks into the greenest eyes she’s ever seen before Theo lays the cat reverently on her lap.

The flowers are lovely, but Anne thinks there’s nothing more beautiful than a cat, and what’s more beautiful still, her mere presence makes him purr. He’s the perfect lap cat. No squirming, the front paws crossed neatly one over the other on her thigh, content to be with her. Thank you thank you thank you. “Does he have a name?”

“Caesar.”

“Hasn’t anyone been feeding him?” The fluffy fur hides it, but he’s scrawny. When she strokes him, he’s all skin and bones. “Sweetheart,” she says. She lifts and kisses the little black head. Oh, those green eyes. She has never seen eyes that green. Anne strokes the fur. She scratches the ears. “Liza, come pet him.” The girl grew up deprived. To Patrice, all animals are dirty.

What a shame, Liza thinks, that she won’t be allowed to keep him.

Shadows dance outside on the cinderblock wall. “We’ve got the evening wind,” says Anne. “Theo, be a dear. Turn off the A/C and open the door,” and in comes the scent of star jasmine. Birdsong. “And the windows.” An automatic garage door going up sounds like her hard drive does when she fears it’s going to crash.

Liza strokes the cat. “He isn’t moving at all,” she says. “Shouldn’t he be—?”

Anne pinches off a bit of cheese and offers it. Caesar shows no interest. “Theo, did you drug this poor creature to keep him still?”

“The cat is dying,” he says, but they don’t understand. “Caesar purrs because he thinks you can help.”

Anne’s voice comes out, hoarse. “Take this animal away from me,” which is not what the Savior would say. Not at all.

“The green eyes are too brilliant,” he says. “Cancer of the liver. Jaundice.”

“Liza, take this—”

“While I was at Oxford, my mother died,” he says. And no one moves. The cat remains on Anne’s lap. “I didn’t even know she was ill. She was buried before anyone told me.” And he’d gone to his tutor and his seminar and he walked around going through the same daily routine, wearing the same clothes, looking indistinguishable from the Theo of the day before. A person passing him on the street could not have known.

“I’m sorry,” Liza whispers.

She doesn’t understand.

“My mother,” he says. When she was gone—she was the origin, and without her, it was though his very existence was thrown into doubt. He experienced the emptiness of matter. He’d be sitting on a chair or walking down a street, and suddenly feel himself plunging through empty space, spinning in the vacuum. Lost in the absence between atoms.

“All that is solid melts into air,” he says. I’m not crazy, he thinks. I am not mad. “I discovered your notes, Dr. Easley, and I felt not just reconciled, but emboldened.” He’d gone down to London and walked and walked and realized he had no way of knowing what was carried in the hearts of the people he passed. Any one of them might carry some terrible secret grief. They all looked so fragile then, like little bits of vivified matter trying to stand their ground against the void. His mother’s death had taught him this and so he treated people more gently. For a while. It wore off, as it would have to do. “I met you. A simple glance at you does not reveal your radiance. And I thought for the first time, what if someone among us carries not pain but a secret hidden glory? What if we must treat each and every person as if he or she is the One?”

“Each and every person, Theo,” says Anne. “You as much as I.”

“No,” he says. It was her vision: interaction, not force; unity, not broken discontinuities. Her supernal radiance, the flowers. “What if you are?” he asks. “I mean, of course, you aren’t, but—”

“Theo,” she says.

“You refused to develop weapons!”

“Oh, please. I was a mindless little patriot. If you’d known me—It just happens that curiosity led me in another direction. Just as your curiosity led to the book.”

“It led you to the Truth,” he says.

“To a hypothesis. And what you’ve written about me is not true.”

He hadn’t really believed it—had he?, but given the world they lived in, was it so wrong to long for the advent of the Prince of Peace? Hope may be as difficult to sustain as grief but surely, he thinks, they sustain each other.

Theo closes the door. Locks it. With the A/C turned off, it’s already hot in the room, the sun still filtering through dusty glass as he tries to remember what the gun in his luggage has to do with compassion.

“Sometimes I can’t bear what I see,” he says. He crouches by his carry-on and unzips the pouch. He tries to look into Anne’s eyes but his own eyes blur a moment and then he takes out the gun. “If God were here, in human form,” he says, “I would hold this gun to His head.”

The steel feels so cold in his hand, as if refrigerated. For a moment he believes he’s holding the gun to give it comfort, to warm it. He thinks of all the sensationalized crimes of passion, the woman saying Yes, I had the gun, but I never meant to use it. How false her words, her bewilderment always sounded, until now.

Liza, breathe in, breathe out, keeps her eyes on him as he imagines firing into his own head, the bullet flying between the atoms, missing every bit of matter, as Anne thinks, yes, it was always clear I moved into this room to die. She says, “Is that thing loaded?”

“Only one chamber,” he says and still can’t imagine how he got here. He has made himself a vacuum in order to be filled and then the words come: “It’s a tangerine.”

“Mais non,” says Anne and then, to Liza’s horror, “Ceci n’est pas une pipe.”

No, he thinks, tangerine is an excuse, an explanation, a way to stop this from going further. And so he talks of accidents, contingencies. Things that occur that need not have occurred. “Oxford is done for me. The book’s a failure. I’ll never write another. There’s nothing left but to teach schoolchildren.” He talks of predictions, trajectories, the unique structural signature of the barrel. The six chambers. “A lesson in probability,” he says.

Liza can’t stop herself: “You’re not actually planning to take that into a classroom.”

“Just to get their attention,” he says. “If I spin it, point it— Am I more likely to fire if it’s pointed like this—” He aims the gun at Liza. “Or like this?” He holds the gun to his own skull. Lowers it. “It may only appear that I have a choice.” He shoves the barrel into his mouth. Then removes it because if everything is one, what does it matter that his mother’s dead? “The shallowness of contemporary life,” he says, because Anne, only Anne can understand him, but he doesn’t complete the thought, unable to criticize the shallow earth she’s come to save.

“I demand a sign,” he says. “Reveal yourself.” His mind has gone somewhere it ought never to have gone. “Save the cat,” he says.

She can’t speak. She cannot enter his delusion. She feels the warmth beneath her hand, the electric purr.

“What are you afraid of, Dr. Easley? It can be a bitter cup, but you mustn’t draw back. When you were a child, didn’t you know you had a mission here on earth?”

Yes, and all children do, she thinks, Liza, and Theo, too.

“You withdrew from the world. You abandoned us. But you can’t keep yourself remote from the suffering. You can’t ignore this creature before you.” He has risked everything and for nothing unless he can force her out of hiding. “Show your face. Your power.”

Anne strokes the black fur and says, “I have no power. Liza, please. Get this animal away from me.”

“Unleash it,” he says to Anne. “Like the atom. The world is going to hell and you won’t even try! You—could—make—things—change.” He holds the gun to Anne’s head and says, “I anointed you.”

Anne pushes Caesar off her lap. The cat lands with a soft mewling cry and a thud.

He says, “I believed you could stop me.”

“Theo,” cries Liza, “you wrote a really good book.”

He could kill her for that. He fires.

The room shakes as Anne pitches forward from her chair. Legs numb, she falls.

On the floor, she gathers to her lap the ruined body of the cat and Theo is frozen a moment by the sight—the Pietà—before he runs.

“We should call the police,” says Liza.

“No! Treat him gently.” Is he dangerous? Anne can’t predict. Out the window, on the cinderblock wall, she sees a large mouse-colored head come out from between the painted wrought-iron spikes. A naked tail curls among the morning glory vines. Remarkable creature and Theo is every bit as remarkable. Iliked him, she thinks. I still like him.

“Why isn’t anyone coming?” Liza says. “I thought this place took good care of you. They must have heard the shot.” They listen for sirens. A dog barks in the distance. A car alarm.

In the courtyard, Theo drops the gun into the artificial pond, startling a turtle that drags itself up upon a rock. He sees the jewel-like colors as it stretches out its neck to lay its head on another’s sun-warmed shell. He sits on the bench and waits for the police but no one comes. Where will I go now? Where will I lay my head?

Liza is trembling, exhilarated and terrified. Just don’t let Patrice find out. She’s had a gun aimed at her head and the worst of it is she’s more afraid of what her mother will say. How ridiculous. Liza starts to laugh. Her aunt is making sounds, choking, stifled. Liza helps her to her feet. There’s feline blood now on her St. John suit, and her aunt is laughing and holding up her hands: “Theo left too soon,” she says. “The stigmata!”

Anne sways her way to the bedside table where Liza left Amber and Fur. “You should have had him sign your copy.” She carefully opens the cover, presses her bloody palm print on the title page. “There. Patrice can put it up on Ebay.” She makes a joke of everything. She starts to cry.

Liza wants to go to her and hold her. Instead she gets the basin and a towel and washes the blood from her aunt’s hands. She could be cleaning Victoria’s sticky fingers, or murmuring the way she once did to calm Minou, when she held the cat to keep it from squirming as her aunt clipped its nails. She feels sick with dread, not at the blood, but the memory of how her own child’s dirty fingers had repelled her. She’s dizzy for a moment with longing—for Victoria, for Keith.

If an extraterrestrial were regarding us from outer space, Anne thinks, would we be tiny dots, or a barely detectable shift in energy?

He had asked her: “Do you believe in extraterrestrials, Dr. Easley?”

She’d answered: “Do you?”

“I want to,” he said. “I need to believe that somewhere in the universe there’s something better than us.”

Poor Theo.

“You have a car,” Anne says. “Let’s go out to dinner. Somewhere nice.”

No feelings, Liza thinks. And she’s the good sister. “I have the Zagat guide,” she says.

Anne thinks if I had the power, I would have saved him. She thinks of all the medical tests she’s been through, all the X-Rays, all the imaging, and yet no one has ever seen inside her.

“Come to Boston,” Liza says.

“Tomorrow I want to look for an apartment. Not in Boston. Here.”

“For a visit.” Liza studies her aunt’s fingernails, short and unpolished, almost unnaturally even. “I want Victoria to know you.”

Seven years of suspended animation, thinks Anne, passed now in a flash. What a sad old marvelous world it is and now she’s going to see more of it, free to stumble as she makes unsteady progress to the end.

“We’ll find you an apartment before we go to Boston,” says Liza, “A landlord who allows cats.”

Theo’s gift: this unforeseen result.

“Thank God,” says Anne. “In a manner of speaking, of course.”

–By Diane Lefer

See Diane’s nonfiction at LA Progressive. She is an associated artist with ImaginAction. See her on Cynthia Newberry Martin’s blog Catching Days, and an interview in Taco.

Completed in 1872, College Hall rises atop Seminary Hill. The venerable building originally served as a theological seminary and was constructed on the remains of a Civil War hospital for chronically ill vets. College Green once served as a racetrack and fairgrounds. I found no mention of ice rinks or July 4th softball games. The pipe organ was installed in 1884.

Completed in 1872, College Hall rises atop Seminary Hill. The venerable building originally served as a theological seminary and was constructed on the remains of a Civil War hospital for chronically ill vets. College Green once served as a racetrack and fairgrounds. I found no mention of ice rinks or July 4th softball games. The pipe organ was installed in 1884.