Two great Irish poems, a debt to Wordsworth, and Patrick J. Keane‘s synthetic/syncretic mind teach us here how to draw value from humble things in time of trouble (our time, among others) and offer a plea for significance enacted in Derek Mahon’s line “Let not our naïve labours have been in vain.” This plea rings through the ages but also presently, here and now, with the economy in tatters, the 99% grinding lower and lower, the massive direction of things against us. Why write, why persevere, what point? Pat Keane, as usual, with his vast reading, snatches references and parallels out of the ether, but he never fails to draw a passionately political moral out of the poetic argument.

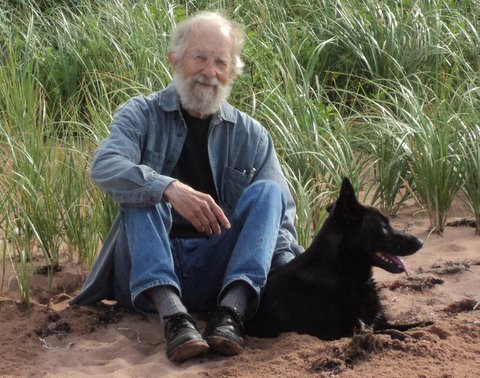

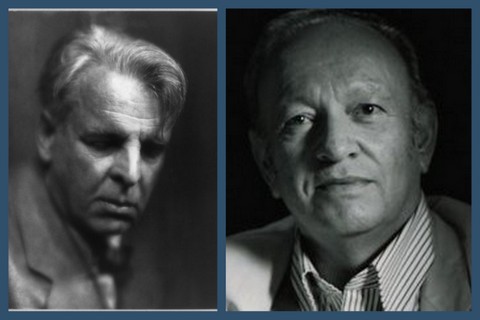

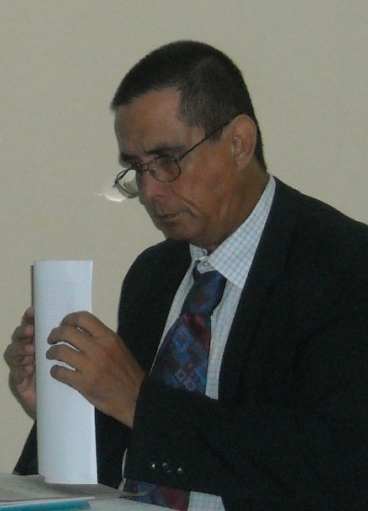

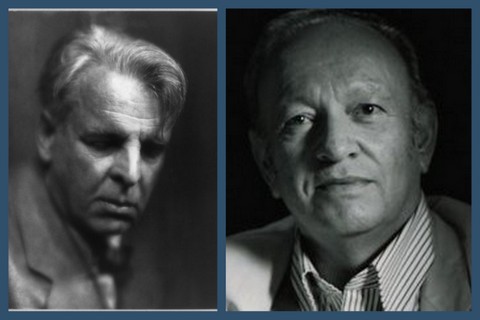

The Yeats photo above is by Pirie Macdonald and the Mahon photo is by John Minihan.

dg

§

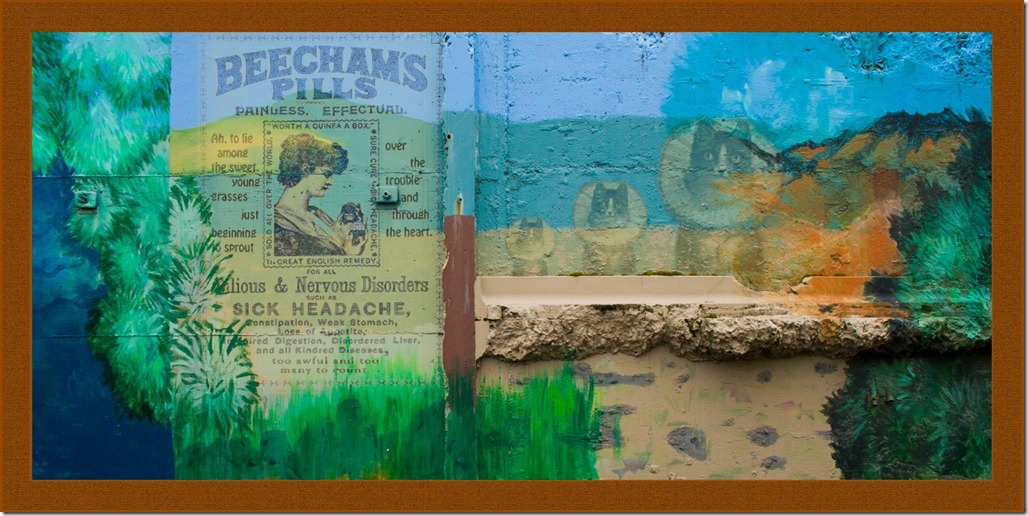

Instead of dirt and poison we have rather chosen

to fill our hives with honey and wax;

thus furnishing mankind with the two noblest of things:

sweetness and light.

—Jonathan Swift, The Battle of the Books

—–

To her fair works did nature link

The human soul that through me ran,

And much it grieved my heart to think

What man has made of man.

—William Wordsworth, “Lines Written in Early Spring”

§

The human cry for deliverance from pain and suffering, from violence and violation, whether personal or political or both, comes in many forms, some quite unexpected. Here are two poems written half a century apart. Both are by Irish poets, both have to do with the Irish Civil War (1922-23), and both radiate out from a focus on minute particulars to embrace universal meaning.

The first is by W. B. Yeats, Ireland’s greatest poet and widely considered the major poet of the twentieth century. It is the sixth lyric in Meditations in Time of Civil War, a poetic sequence Yeats wrote in the midst of that tragic conflict, a war fought between supporters of the new Irish Free State, which emerged from the Anglo-Irish Treaty following the War of Independence, and Republicans who rejected the terms of that Treaty, ratified in January 1922. The anti-Treaty forces objected particularly to the required oath to the British king and to the partition between predominantly Protestant Northern Ireland and the rest of the island. To clarify the title: a “stare” is the west-of-Ireland name for a starling; the “window” is in Yeats’s tower, an ancient Norman tower he purchased in 1917 and restored for his wife. The poet, now 57, and his young wife and two children were living there during much of the Irish Civil War.

The Stare’s Nest by My Window

The bees build in the crevices

Of loosening masonry, and there

The mother birds bring grubs and flies.

My wall is loosening; honey-bees

Come build in the empty house of the stare.

We are closed in, and the key is turned

On our uncertainty; somewhere

A man is killed, or a house burned,

Yet no clear fact to be discerned;

Come build in the empty house of the stare.

A barricade of stone or of wood;

Some fourteen days of civil war;

Last night they trundled down the road

That dead young soldier in his blood;

Come build in the empty house of the stare.

We had fed the heart on fantasies,

The heart’s grown brutal from the fare;

More substance in our enmities

Than in our love; O, honey-bees,

Come build in the empty house of the stare.

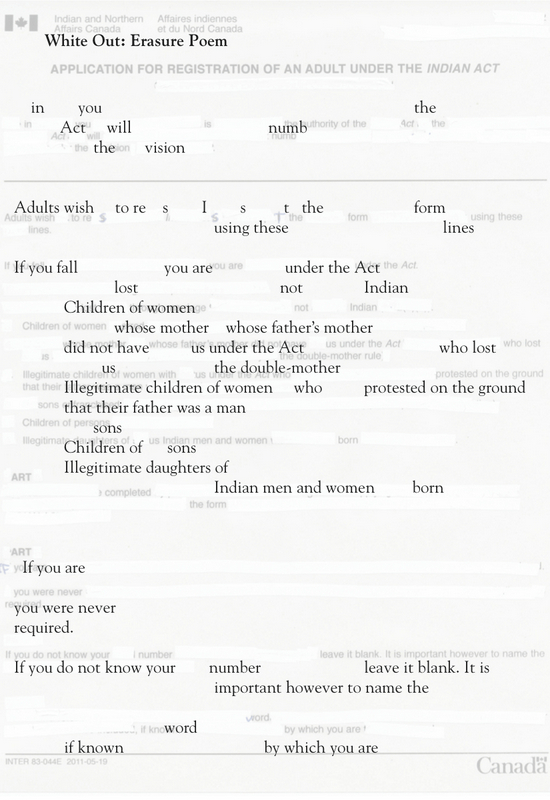

The second poem, “A Disused Shed in Co. Wexford,” is by the Northern Irish poet Derek Mahon. It was written soon after Bloody Sunday, the day in 1972 when British paratroopers fired into a crowd of Catholic protesters, initiating the violent stage of the Troubles in Northern Ireland. Mahon wants his readers to associate that event with the Partition of Ireland back in 1922 and the subsequent Civil War. The poem is dedicated to J. G. Farrell, whose 1972 novel, The Troubles, has a scene including an old shed on the grounds of one of the many buildings burned down during the Irish Civil War. Mahon’s “disused shed” is on the grounds of “a burnt-out hotel,” burned down—like Farrell’s and like the “house burned” in Yeats’s poem—during “civil war days.” In the midst of destructive violence and embittered hearts, Yeats’s own heart reaches out to birds that nurture rather than kill, and bees that build rather than destroy. In an even wider historical context of exploitation, loss, and destruction, Mahon’s empathetic heart goes out, remarkably, to neglected mushrooms in a long-abandoned shed, “waiting for us” for precisely “a half-century, without visitors, in the dark.”

Mahon’s deeply humane, obliquely political poem is considered by many readers the single greatest lyric to have come out of Ireland since the death of Yeats—especially high praise considering the quality of the poetry produced over the past three decades by Ireland’s preeminent contemporary poet, Seamus Heaney, widely regarded as a worthy heir to Yeats. Appropriately, in accepting the Nobel Prize for Literature in 1995, Heaney celebrated Yeats, his predecessor as Nobel Laureate, singling out for special praise “A Stare’s Nest by My Window,” a poem often quoted (as he notes in his acceptance speech) by men and women during the later Troubles in Northern Ireland. Along with having particular resonance for those who lived through one or the other of the two phases of the Irish Troubles, these poems by Yeats and Mahon are of universal significance. Both have roots going back to Wordsworth, writing during the era of the French Revolution, and they seem relevant to our current troubles: to a world in economic, political, and ecological crisis, and to our own polarized nation, marked by increasingly bitter partisanship and a widening gap between the rich and the rest, the comfortable and a majority struggling to survive.

A Disused Shed in Co. Wexford

Let them not forget us, the weak souls among the asphodels.

…………………………………..Seferis, Mythistorema

Even now there are places where a thought might grow—

Peruvian mines, worked out and abandoned

To a slow clock of condensation,

An echo trapped for ever, and a flutter

Of wildflowers in the lift-shaft,

Indian compounds where the wind dances

And a door bangs with diminished confidence,

Lime crevices behind rippling rainbarrels,

Dog corners for bone burials;

And, in a disused shed in Co. Wexford,

Deep in the grounds of a burnt-out hotel,

Among the bathtubs and washbasins

A thousand mushrooms crowd to a keyhole.

This is the one star in their firmament

Or frames a star within a star.

What should they do there but desire?

So many days beyond the rhododendrons

With the world waltzing in its bowl of cloud,

They have learnt patience and silence

Listening to the rooks querulous in the high wood.

They have been waiting for us in a foeter of

Vegetable sweat since civil war days,

Since the gravel-crunching, interminable departure

Of the expropriated mycologist.

He never came back, and light since then

Is a keyhole rusting gently after rain.

Spiders have spun, flies dusted to mildew,

And once a day, perhaps, they have heard something—

A trickle of masonry, a shout from the blue

Or a lorry changing gear at the end of the lane.

There have been deaths, the pale flesh flaking

Into the earth that nourished it;

And nightmares, born of these and the grim

Dominion of stale air and rank moisture.

Those nearest the door grow strong—

“Elbow room! Elbow room!”

The rest, dim in a twilight of crumbling

Utensils and broken flower-pots, groaning

For their deliverance, have been so long

Expectant that there is left only the posture.

A half-century, without visitors, in the dark—

Poor preparation for the cracking lock

And creak of hinges. Magi, moonmen,

Powdery prisoners of the old regime,

Web-throated, stalked like triffids, racked by drought

And insomnia, only the ghost of a scream

At the flash-bulb firing squad we wake them with

Shows there is life yet in their feverish forms.

Grown beyond nature now, soft food for worms,

They lift frail heads in gravity and good faith.

They are begging us, you see, in their wordless way,

To do something, to speak on their behalf

Or at least not to close the door again.

Lost people of Treblinka and Pompeii!

“Save us, save us,” they seem to say,

“Let the god not abandon us

Who have come so far in darkness and in pain.

We too had our lives to live.

You with your light meter and relaxed itinerary,

Let not our naïve labours have been in vain!”

These poems speak for themselves; but, having briefly introduced both, I’d like to now venture commentaries on each, beginning with “The Stare’s Nest by My Window.”

*

Aside from the opening poem, “Ancestral Houses” (written in 1921), the seven lyrics that make up Meditations in Time of Civil War were written, Yeats tells us in his own note to the sequence, “at Thoor Ballylee in 1922, during the civil war.” As published in 1923, the sequence reflects upon, and dramatically records, the internecine violence swirling around the poet’s own tower in the west of Ireland, nowhere more poignantly than in the sixth poem, “The Stare’s Nest by My Window.” Like Wordsworth before him, also writing in a time of war and personal crisis, Yeats, experiencing a sense of what he called “the common tragedy of life,” focuses on small, common things of nature—here, bees and mother birds that “bring grubs and flies” to their chicks. Living in a restored twelfth-century Norman fortress, the poet was fully aware that men in this region had “lived through many tumultuous centuries.” Now, having watched stacked coffins carted past his door and heard night explosions, Yeats, as he tells us in his Nobel Prize memoir, “felt an overmastering desire not to grow unhappy or embittered, not to lose all sense of the beauty of nature” (“The Bounty of Sweden” [1925], in Autobiographies, 579-80).

Surrounded by human destructiveness (young soldiers slaughtered, great houses burned), Yeats attends to the constructive continuities of the natural world: the bees that “build” in the “crevices” of his tower’s loosening masonry, and the life-affirming feminine principle in the form of “mother birds” who bring sustenance to their nested young. In the refrain, the poet, by nature a creative spirit, even if his own “wall is loosening” (here he merges the ancient tower with his own aging body) invokes related creative spirits: the “honey-bees,” comb-makers and confectioners of a substance associated with sweetness and light. The bees are to “Come build in the empty house of the stare.” It’s not quite clear if the stares or starlings, rather quarrelsome and rapacious birds, have abandoned their nest, to be replaced by other birds, or if the “mother-birds” are themselves starlings. What is clear is that (to cite John Keats’s depiction of nature’s continuity) “the poetry of earth is ceasing never,” and that Yeats associates the bird feeding her young with the honey-bee, an archetypal image of harmony and regeneration.

As a young reader of Walden, Yeats famously longed, emulating Thoreau, to “build” a small cabin on the Lake Isle of Innisfree, with “a hive for the honey-bee,/And live alone in the bee-loud glade.” That was Then; Now he is writing “in time of civil war.” Unlike instinctual creatures who build and nurture, “we,” even non-participants in the violence, are caught up in, and cut off by it. In the isolation of his lonely tower, the poet and his family are—rather like Mahon’s mushrooms—“closed in, and the key is turned/On our uncertainty.” In the fog of war, with communications down, facts are the first casualty, an “uncertainty” compounded by the nature of this worst form of conflict. As is made clear by the full sequence of which this lyric is part, Yeats (though he accepted the Treaty) was ambivalent about a tragic civil war that had pitted brother against brother, creating “a whirlpool of hate” for which he felt “both sides were responsible” (1923 letter to Lady Gregory). One can argue either side of the political division that led to the conflict; Yeats himself refused (as he said in the letter to Lady Gregory) to “take any position in life where I have to speak but half my mind.” There are, however, a few lethal certainties: While “no clear fact” is to be discerned, “somewhere/ A man is killed, or a house burned.”

One day Yeats saw “the smoke made by the burning of a great neighboring house,” and, along with stacked coffins, actually witnessed the incident presented in the third stanza, also described in a letter to the critic F. J. C. Grierson. His graphic specificity and use of the demonstrative pronoun create the stark immediacy epitomizing and particularizing the horror of war: “Last night they trundled down the road/ That dead young soldier in his blood.” That close focus on the dead, in sharp contrast to the equally close focus on the details of the life-affirming birds and bees, is followed by a third invocation for those bees to build. In “Lines Written in Early Spring,” Wordsworth had asked, rhetorically, “Have I not reason to lament/ What man has made of man?” Yeats renews that Wordsworthian contrast between the creative harmony of nature and the destructive tendencies of man: man caught up in the political world that is too much with us, and so cut off from and out of tune with the vital, fecund universe.

In the great final stanza, Yeats out-Wordsworths Wordsworth, making himself complicit in the very violence he deplores. “We” are not merely the closed-in, passive endurers of heart-hardening brutality, but its inadvertent engenderers. The maternal birds bring their young substantial fare in the form of life-sustaining grubs and flies. But “We had fed the heart on fantasies,/The heart’s grown brutal from the fare.” Prominent among those “fantasies” were the potent myths, masculine and feminine, of Cuchulain and Cathleen ni Houlihan. In resurrecting both mythic figures, abstractions blooded, Yeats had fed Irish nationalism, a passion alternately ennobling and fanatical—all that delirium of the brave.

Having written a cycle of five plays based on Cuchulain, the Achilles of ancient Irish epic, Yeats seems, in his late poem “The Statues,” at once proud and disturbed that Padraic Pearse and some of the other leaders of the Easter Rising had made a cult of the ancient Irish hero Yeats had revived, in the process unleashing an uncanny power: “When Pearse summoned Cuchulain to his side,/What stalked through the Post Office?” To this day, Oliver Shepherd’s bronze statue of Cuchulain may be seen in the General Post Office, the building on Dublin’s O’Connell Street in which Pearse, James Connolly, and a youthful Michael Collins, among others, made their stand in the Easter Rising. In “The Man and the Echo,” another late poem, one written not long before his own death, Yeats posed another political question, perhaps the most famous in Irish literature: “Did that play of mine send out/ Certain men the English shot?” He was referring to Cathleen ni Houlihan (1902), written for and starring his beloved, that beautiful patriotic firebrand, Maud Gonne; and the answer to the question is Yes. Young men inspired by that patriotic, even propagandistic, glorifying of blood sacrifice for Mother Ireland would later lose their lives in the Easter Rising (1916), or in the Anglo-Irish War (1919-21).

“Too long a sacrifice/Can make a stone of the heart,” Yeats reminded us in ambivalently commemorating (in his group-elegy, “Easter 1916”) the leaders of the Rising executed by the British. But then, their hearts still deeply moved, yet often brutalized, by mythic fantasies, Irish patriots would turn against each other in the Civil War, displaying “More substance in our enmities/ Than in our love.” In the form of sectarian conflict between Catholic and Protestant, vestiges of love-eclipsing hatred survive in the not yet fully resolved Troubles in Northern Ireland. James Joyce had addressed the issue in Ulysses, set in 1904 but published in 1922, during the Irish Civil War. In “Cyclops,” the political episode of his novel, Joyce’s unlikely hero, Leopold Bloom, responds to the one-eyed Irish chauvinism he encounters in Barney Kiernan’s pub:

–But it’s no use, says he. Force, hatred, history, all that. That’s not life for men and women, insult and hatred. And everybody knows that it’s the very opposite of that that is life.

–What? says Alf.

–Love, says Bloom. I mean the opposite of hatred. (Ulysses, 273)

Having helped create a mythology that had turned into bloody reality, a lethal hatred “the very opposite of that that is life,” Yeats also envisions, nowhere more movingly than in “The Stare’s Nest by My Window,” the opposite possibility. As he put it in a letter written in the midst of the Civil War, “The one enlivening truth that starts out of it all is that we may learn charity after mutual contempt.” Enlivening: Life might yet issue from death, sweetness flowing into the breast once political bitterness had been cast out. In this sequence’s opening poem Yeats referred to “violent, bitter men,” and to “the sweetness that all longed for night and day.” This sixth poem in the sequence invokes creatures emblematic of that sweetness. Appropriately, the prayer for regeneration intensifies, and is most poignant, in the final supplicant refrain, with its direct and tender apostrophe: “O, honey-bees,/Come build in the empty house of the stare.”

This longing is a prayer for love among the ruins, plenitude amidst desolation; a cry from the heart for sweetness and light to replace embittered darkness. Filling emptiness, the honey-bees represent creative, natural, benevolent cyclicity in contrast to the destructive, unnatural brutality of civil war. What better image for a poem seeking reconciliation of civil enmity? “So work the honey-bees,” says Shakespeare’s Archbishop of Canterbury, “Creatures that by a rule in nature teach/ The act of order to a peopled kingdom” (Henry V, I.ii.187-89). It is no accident that Seamus Heaney, in choosing jacket art for Crediting Poetry, the published version of his 1995 Nobel Prize Acceptance speech, selected The Bees (from the Ashmole Bestiary, circa 1210), an illustration intended to refer back to this poem by Yeats, a poem especially “credited” in the speech. Thinking of Yeats’s and Shakespeare’s honey-bees, perhaps of Mandeville’s Fable of the Bees, and surely of Swift’s praise of honey and wax emblematic of “sweetness and light,” Heaney notes the special significance of the honey-bee—“an image deeply lodged in poetic tradition and always suggestive of the ideal of an industrious, harmonious, nurturing commonwealth” (Crediting Poetry, 44-45).

*

We encounter another image from the world of nature, though one far less conventional, in Derek Mahon’s poem, which replaces Yeats’s honey-bees with a commonwealth of mushrooms. The poetic means by which Yeats moves us go, of course, beyond the resonant image of the honey-bee. His poem is intricately and regularly rhymed, its strict abaab stanza form subtly nuanced by enjambment and oblique rhymes in the a lines of each stanza, anchored and stabilized by the single b rhyme on “stare” throughout the poem. Mahon’s “A Disused Shed in Co. Wexford,” though far more loosely rhymed and even more colloquially enjambed, is also highly formal—and, as we will see, or hear, remarkably allusive. It consists of six 10-line stanzas, with lines varying between approximations of iambic tetrameter and pentameter. Yeats found his theme in a precise place (an “empty” yet life-filled crevice near the bedroom window in his tower); Mahon begins by enumerating various “places” where a “thought might,” almost organically, “grow.” Those he mentions, before homing in on the precisely-placed disused shed, adumbrate his themes of exploitation, loss, abandonment, and the slow passage of time.

“Even now,” there are, in his opening example, Peruvian silver mines, once teeming with natives forced to labor in the darkness by exploitative Spanish conquistadores, mines now “worked out and abandoned/To a slow clock of condensation,/An echo trapped for ever…” The ticking off of the hard cs (worked, clock, condensation, echo) is balanced by fluid ls, fricative fs, and short is: a haunting delicacy—“a flutter/ Of wildflowers in the lift-shaft”–reminiscent of Keats’s goddess of Autumn, her “hair soft lifted by the winnowing wind.” From these “Indian compounds” the Indians themselves have long since vanished; now only the “wind dances,” and a door bangs “with diminished confidence.” The challenge, for Mahon as for late summer’s oven-bird in Robert Frost’s poem of that title, “is what to make of a diminished thing,” especially given the even more unpromising sites in this opening stanza: lime crevices hidden behind rain-barrels, or remote corners where dogs have buried bones or feces (Mahon originally referred to “dog corners for shit burials”).

The first stanza, which concludes by casually introducing the titular “disused shed in Co. Wexford,” pivots syntactically into the second stanza, which locates that shed “Deep in the grounds of a burnt-out hotel…” Mahon seems again to be echoing Keats, this time his Hyperion, which opens with fallen, gray-haired Saturn, found “Deep in the shady sadness of a vale/ Far sunken from the healthy breath of morn,/ Far from the fiery noon and eve’s one star…(1-4). The echo is sustained in Mahon’s description of the shed’s inhabitants, a “thousand mushrooms” crowded to a keyhole, the “one star in their firmament,” the “star” of that keyhole framing within it an actual evening star. Again, the question is what to make of a diminished thing. “What should they do there but desire?” Having survived “so many days” beyond even the evergreen rhododendrons, while the great world waltzes gaily and unconcerned in its amphitheater of cloud, the mushrooms “have learned patience and silence/ Listening to the rooks querulous in the high wood.” With the concealed effortlessness of an art great enough to induce the Coleridgean suspension of disbelief that constitutes poetic faith, Mahon has brought us, amazingly enough, into the otherwise inexpressible, unconscious world of abandoned mushrooms, vegetative forms made as hauntingly real as the housed ghosts in Walter de la Mare’s “The Listeners.”

In fact, listening patiently and silently, they have been “waiting for us”—waiting for those who break into their shed in the penultimate stanza and those of “us” who read Mahon’s poem when it first appeared in 1972—for “a half century,” ever since “civil war days.” Back then, in 1922, the botanist who tended to them (the “expropriated mycologist”) was removed from those chores among the fungi, called to duty in the Irish Civil War. The mushrooms, always listening, mark his “gravel-crunching departure,” a departure that proved to be “interminable.” Presumably killed in action, he “never came back, and light since then/ Is a keyhole rusting gently after rain.” Equally gently, and elegiacally, the years are telescoped. Through decades, while “spiders have spun, flies dusted to mildew,” the abandoned mushrooms survive in their constricted shed, isolated and forgotten. Still, clinging tenaciously to their pitiably minimal existence, they listen in the darkness, and

Once a day, perhaps, they have heard something—

A trickle of masonry, a shout from the blue

Or a lorry changing gear at the end of the lane.

Not all these attentive auditors have survived the half century they have been patiently waiting for us. “There have been deaths, the pale flesh flaking/ Into the earth that nourished it”; and “nightmares,” engendered by that decay and the nourishing and receiving earth. In this “grim/ Dominion of stale air and rank moisture,” the mushrooms nearest the door “grow strong,” struggling for their own mini-dominion: “Elbow room! Elbow room!” (This welcome note of jocularity is unlikely to derive from a recollection of King John, Shakespeare’s poisoned and dying wretch of a monarch, who cries out in the final scene of the play, “Now my soul hath elbow-room” [King John, V.vii.28]. Instead, Mahon is probably echoing the exuberant exclamation (popularized in a poem by Arthur Cuiterman) attributed to America’s expansive Kentucky frontiersman: “’Elbow room!’ cried Daniel Boone.”) Even in the claustrophobic shed-world there are winners and losers, the aggressive and the near-defeated. Those in the mushroom colony nearest the door grow strong;

The rest, dim in a twilight of crumbling

Utensils and broken flower-pots, groaning

For their deliverance, have been so long

Expectant that there is left only the posture.

In this evocation of the pathos of mutability, diminished but still stubborn hope, and sheer survival among the crumbling and broken detritus, Mahon combines a question and answer from Paul’s Epistle to the Romans. “Who shall deliver me from the body of this death?” the Apostle asks, adding “For we know that the whole creation groaneth and travaileth in pain until now” (7:24, 8:22). The mushrooms have been “so long/ Expectant” that they retain only the tendency to believe in their deliverance, only a “posture” or anticipatory attitude. Yet they remain poignantly open to that equilibrium of faith and tragic realization expressed in the final line of Wordsworth’s “Elegiac Stanzas”: “Not without hope we suffer and we mourn.”

Yet, however expectant the mushrooms may be, deliverance, when it comes, comes unexpectedly, as a shock—a sudden, violent, cacophonous violation of the silent loneliness of these long-neglected shut-ins:

A half-century, without visitors, in the dark—

Poor preparation for the cracking lock

And creak of hinges.

In a remarkable fusion, the wise old “magi”-like mushrooms are compared to “moonmen” and sci-fi “triffids.” Sufferers racked “by drought and insomnia,” they are also depicted as “Powdery prisoners of the old regime,” victims resembling the few frail, long-forgotten prisoners released from the Bastille at the symbolic onset of the French Revolution. Reinforcing the allusion to that era, their survival is confirmed by a detail—“only the ghost of a scream/ At the flash-bulb firing squad we wake them with…”—that momentarily aligns the tourists armed with cameras with the French firing-squad of regimented automatons executing the Spanish rebels in Goya’s masterpiece, The Third of May, 1808, in Madrid: The Shooting on Principe Pio Mountain. The victims in Goya’s painting are dead, dying, or waiting their turn; the focal point a white-shirted peasant kneeling on the bloodstained earth, his face and posture a remarkable mixture of human horror, pride, and fatalistic resignation in the face of death. Though the mushrooms, awakened by the camera flash, are being photographed rather than actually “shot,” it is not hard to imagine a memory of Goya’s great painting entering into Mahon’s description of the “posture” of his long suffering but dignified mushrooms, and the frightening effect on them of this “flash-bulb firing squad.”

And it is necessary that we again experience the mushrooms’ plight as victims since they have just been described, semi-realistically, as “Web-throated, stalked like triffids”—resembling, that is, the fictional plants in John Windham’s post-apocalyptic novel, The Day of the Triffids (1951). Windham’s bestial plants are, like Mahon’s mushrooms, capable of rudimentary human behavior; indeed, able to uproot themselves and walk, even to communicate with each other. But they are malign, voracious creatures. Any vestigial negative connotation attached to the mushrooms is dissolved in this re-emphasis on their victimage, and in the profoundly moving picture that follows the quasi-military firing of the flash-bulbs. The sudden light wakens them, revealing them at their noblest, most human, and most poignant. Their “ghost of a scream”

Shows there is life yet in their feverish forms.

Grown beyond nature now, soft food for worms,

They lift frail heads in gravity and good faith.

That magnificent last line is at once richly alliterative, paradoxically witty (frail heads lifted in gravity), heartbreakingly vulnerable, and a tribute to inextinguishable hope. What more is there to say? Yet Mahon risks everything in the final stanza, taking the chance that his poem might over-reach by incorporating the marginal life of these forgotten mushrooms, neglected “since civil war days,” within a larger moral and historical background of catastrophe: the human tragedy of Treblinka, the natural disaster of Pompeii. Silent auditors till now, they are given speech in the final lines—“wordless” speech in the obvious sense that the words are supplied (as in the earlier and amusing cry for “Elbow room!”) by the author. Risking all, specifically the danger that his poem’s pathos might sink into bathos, Mahon pulls it off, a rhetorical triumph whose glory is humbled by its Wordsworthian attention to the lowly and dispossessed, and by an empathy and in-feeling reminiscent, again, of Keats, whose Grecian urn, a foster-child of “silence and slow time,” suddenly bursts into utterance at the end of the ode. Mahon’s final stanza opens with his mushrooms on the verge of utterance:

They are begging us, you see, in their wordless way,

To do something, to speak on their behalf

Or at least not to close the door again.

They are begging us, all of us who read and permit ourselves to be possessed by this uncanny poem, to “do” something, anything; or, if we fail to act, to say something, to “speak on their behalf.” At the very least, they plead with us not to repeat their abandonment, “not to close the door again.” For a moment the mushrooms metamorphose into the victims of the modern Holocaust or of ancient Vesuvius, appealing directly to us–we mobile tourists and casual recorders of suffering—to bring them salvation, if only in the form of tragic remembrance. Mahon’s epigraph is from the Greek poet George Seferis, a Nobel Laureate who died the year before this poem was written: “Let them not forget us, the weak souls among the asphodels.” Embodying the return of the repressed, those souls, in Mahon’s conscience-stricken expansion, include all those who, throughout human history, have struggled and suffered—isolated, abandoned, forgotten, deprived, dispossessed, destroyed, even incinerated—in a world groaning for deliverance:

Lost people of Treblinka and Pompeii!

“Save us, save us,” they seem to say,

“Let the god not abandon us

Who have come so far in darkness and in pain.

We too had our lives to live.

You with your light meter and relaxed itinerary,

Let not our naïve labours have been in vain!”

This cry out of darkness and pain evokes our noblest human instincts, empathy and compassion. That it does so is a tribute to the poem’s final “tone of supplication.” I borrow the phrase from Seamus Heaney’s Nobel Prize Acceptance speech. Concluding that speech, Heaney, having repeatedly connected the Troubles in Northern Ireland with Yeats’s “Stare’s Nest” poem, turns to lyric poetry’s “musically satisfying order of sound,” which he also illustrates by reference to this particular poem. He finds the satisfaction he seeks in the repetition of Yeats’s refrain, “with its tone of supplication, its pivots of strength in the words ‘build’ and ‘house’ and its acknowledgement of dissolution in the word ‘empty’,” as well as in “the triangle of forces held in equilibrium by the triple rhyme of ‘fantasies’ and ‘enmities’ and ‘honey-bees’…” What Heaney says in the peroration of his Address, celebrating the “means” by which “Yeats’s work does what the necessary poetry always does,” applies as well to the second of our necessary poems, one no less musically satisfying, and no less deeply humane. For Mahon’s poem, too, pivots between strength and supplication, with his cherished mushrooms’ endurance capped by their petition, “Let not our naïve labours have been in vain.” This, as Heaney concludes Crediting Poetry, is to

touch the base of our sympathetic nature while taking in at the same time the unsympathetic reality of the world to which that nature is constantly exposed. The form of the poem…is crucial to poetry’s power to do the thing which always is and always will be to poetry’s credit: the power to persuade that vulnerable part of our consciousness of its rightness in spite of the evidence of wrongness all around it, the power to remind us that we are hunters and gatherers of values, that our very solitudes and distresses are creditable, in so far as they too are an earnest of our veritable human being. (53-54)

Wordsworth, an abiding influence in the work of Heaney, informs both these poems focusing on seemingly insignificant processes of nature: plangent labors, and values, persisting even amid profound distress. William Hazlitt rightly said of Wordsworth, “No one has shown the same imagination in raising trifles to importance”; it was his “peculiar genius,” Walter Pater added a half century later, “to open out the soul of apparently little or familiar things,” especially the small, neglected, humblest details of the natural world. In doing so, he was able to move the empathetic human heart in ways that help account for the emotional impact on us of mother birds and honey-bees, even of neglected but persevering mushrooms. “Tears” are inherent in “things,” Virgil tells us, since “mortality touches the heart” (Aeneid 1:462). With Mahon in mind, though his words apply as well to the most moving of Yeats’s Civil War poems, Denis Donoghue noted “the consolation of hearing that there is a deeper, truer life going on beneath the bombings and murders and torture.” The parent text may be Wordsworth’s Intimations Ode, a poem of loss and recompense even greater than these two great poems, and offering, in its final lines, the humanizing consolation attending our empathetic response, emotional and cognitive, to that deeper, truer life surviving beneath, and above, what man has made of man:

Thanks to the human heart by which we live,

Thanks to its tenderness, its joys and fears,

To me the meanest flower that blows can give

Thoughts that do often lie too deep for tears.

*

By way of coda, I conclude with a poem of my own, not (needless to say) to suggest that it belongs in the company of Heaney and Mahon, let alone of Wordsworth and Yeats, but merely to record my debt to that tradition elegizing the seemingly least significant lives.

In Memoriam: Mug Rinsing

In charge of the files, a Senior Citizen

Whose life seemed just a daily coffee grind,

She finally let the filing fall behind.

A neighbor phoned to say, She won’t be in….

For a week now, the Company’s been bereft

Of the services of Miss–what was her name?

Pre-dated time-sheets blazon forth her fame

Somewhat ironically. One token’s left:

That skoal to the quotidian, her coffee mug,

Ringed with sludge and sour Half ‘n Half,

Squats in her Out Box, ugly epitaph

On an existence rounded with a shrug….

The desk will soon be cleared; those palisades

Of mounting folders scaled; her little hutch

Rifled of its sugar-packs and such

Accumulated junk as sad old maids

Hive against a cold retirement.

Another woman (proximately aged,

According to Personnel) has been engaged.

The pageant blurs, but files do not relent.

Her mug remains: a dull memorial urn;

But caustic soap and rinsing will remove

Vestigial stains, these final trophies of

Another unremarkable sojourn.

In Arthur Miller’s The Death of a Salesman, the understanding wife of the anti-hero pronounces the appropriately named Willie Lowman “a man to whom attention must be paid.” Wordsworth, with the Bible and Milton as precedent, is, of course, the preeminent poet of the lowly, even the “lowliest”—the revolutionary pioneer of a poetry attending to, and commemorating, things beneath the notice of poets before him. It is a poetry of petition: a call to speak for those who cannot speak for themselves, the neglected who suffer even posthumous violation. It is also a poetry of epitaphs—inscriptions for those whose evanescent lives seem writ in water; or, as here, memorialized only by a coffee stain.

Of course, the real memorial is the poem itself. To avoid sentimentality, I employed an impersonal narrative voice, beneath which readers should detect a very different authorial voice. The elderly office worker of my poem may have left behind—at least from the perspective of an indifferent world (replicated in the narrator’s tone)—only that trivial token of her humble existence: a coffee mug whose vestigial stains will soon be washed away, part of this insubstantial pageant faded. Yet she, too, had her life to live, and I found myself, as her fellow-worker and eventual elegist, unwilling to simply let her disappear, her naïve labors in vain. If the poem’s title and stanza-form derive from Tennyson, Wordsworth and Mahon supply its human heart.

.

Afterword on Derek Mahon and W. B. Yeats

I just came across an engaging interview on “The Art of Poetry,” published in the Paris Review in 1981. In it, Derek Mahon made several remarks germane to the preceding essay. “Heaney is a Wordsworth man,” he said. “I’m a Coleridge man.” As a self-confessed traditionalist, Mahon was thinking specifically of Coleridge’s emphasis on “organic form” and the power of what he called in the Dejection Ode his “shaping spirit of imagination.” Asked about the tension between the “formal” and the “wild” aspects of poetry, what Nietzsche, borrowing from the Greeks, called “the Apollonian and the Dionysian,” Mahon described this as the combination that has the greatest potency, the hissing chemicals inside the well-wrought urn; an urnful of explosives. That’s what’s so great about Yeats, after all. The Dionysian contained within the Apollonian form, and bursting at the seams—shaking at the bars, but the bars have to be there to be shaken….That’s true of the ‘Shed’.”

The final reference is, of course, to “A Disused Shed in Co. Wexford,” a whole history of dispossession and violence contained within six carefully-crafted ten-line stanzas. That craftsmanship may, paradoxically, have contributed to an afterthought expressed in this interview. Though he realized that “A Disused Shed,” his most honored and best-loved poem, “meant a lot to a lot of people,” he said that it “now” seemed to him “a rather manufactured piece of work.” Perhaps, as with Yeats and “The Lake Isle of Innisfree,” or Van Morrison with “Brown-Eyed Girl,” he was momentarily wearied of being identified above all as the author of this one poem.

In any case, Mahon is precisely right about what was “so great about Yeats.” Consider, for example, all those great poems in which power is poured into and contained by Yeats’s favorite “traditional” stanza, ottava rima. In fact, it was the Apollonian-Dionysian antithesis in The Birth of Tragedy— the conception of chaos ordered, of Dionysian energy harnessed by Apollo—that first attracted Yeats to Nietzsche, that “strong enchanter” in whom he found what he described, with remarkable tonal accuracy, as “curious astringent joy.” In the late essay intended as a “General Introduction for My Work,” Yeats noted that “because I need a passionate syntax for passionate subject matter I compel myself to accept those traditional metres that have developed with the language. Ezra Pound [and D. H.] Lawrence wrote admirable free verse. I could not. I would lose myself, become joyless” (Essays and Introductions, 522).

This gladly- accepted bondage or disciplined joy—what Yeats, borrowing the term from Mahon’s mentor Coleridge, called “shaping joy”—is what Nietzsche meant by “dancing in chains” (The Wanderer and His Shadow) and being, “in most loving constraint, free” (The Gay Science). Writing to a close friend, Yeats explained this aesthetics of leashed power: “We have all something within ourselves to batter down and get our power from this fighting….The passion of the verse comes from…the holding down of violence or madness—‘down Hysterica passio.’ All depends on the completeness of the holding down, on the stirring of the beast underneath” (Letters to Dorothy Wellesley, 86). The beast must stir, must shake the cage; but, as Mahon notes, the “bars have to be there to be shaken.”

Mahon remarks, early in this interview, that one of his secondary school teachers, John Boyle, taught the poetry of Yeats as the work of “an historian of the time” in which he was living. In “A Disused Shed,” and many other poems, Derek Mahon is an historian of his time, though, in both cases, the response to historical events, however violent, is still cast in traditional form, metrical and stanzaic. In his own response to Irish history, the resurgence of the Irish Troubles to whose initial phase Yeats was responding, Derek Mahon, again like Yeats, refused to take sides if that meant repressing his openness to differing political and cultural perspectives.

Born into a Northern Protestant tradition he found not only limiting, but guilt-inducing, Mahon sought escape through travel and, in his poetry, through an empathetic identification with the victims of history. Confronting the “horror” of the sectarian violence in the North, Mahon told the Paris Review interviewer in 1981, “you couldn’t take sides. You couldn’t take sides. In a kind of way, I still can‘t. It’s possible [ he continued, alluding to the “Disused Shed” poem] for me to write about the dead of Treblinka and Pompeii—included in that are the dead of Dungiven and Magherafelt. But I’ve never been able to write directly about it.”

Why these two towns? In Maghera, 14 people were killed, 10 by the Provisional IRA, in the course of the Northern “Troubles.” And Mahon presumably singled out Dungiven because it was there, on 13 July 1969, that members of the Royal Ulster Constabulary brutally batonned an elderly Catholic farmer. The man, Francis McClosky, who was completely innocent, died from his injuries: a death that many see as the event that initiated the violent phase of the “Troubles” in the North.

To end on a happier note regarding the poetry of Derek Mahon: Following a fallow period of several years, there has been a late flowering. Four excellent collections have appeared in as many years: Harbour Lights (2006); Somewhere the Wave (2007), Life on Earth (2008), and An Autumn Wind (2010), published as the poet was turning 70. It would seem that, like W. B. Yeats, who also experienced a burst of creative energy as he entered his seventies, Derek Mahon has retained his shaping spirit of imagination.

—Patrick J. Keane

————————————–

Patrick J. Keane is Professor Emeritus of Le Moyne College and a Contributing Editor at Numéro Cinq. Though he has written on a wide range of topics, his areas of special interest have been 19th and 20th-century poetry in the Romantic tradition; Irish literature and history; the interactions of literature with philosophic, religious, and political thinking; the impact of Nietzsche on certain 20th century writers; and, most recently, Transatlantic studies, exploring the influence of German Idealist philosophy and British Romanticism on American writers. His books include William Butler Yeats: Contemporary Studies in Literature (1973), A Wild Civility: Interactions in the Poetry and Thought of Robert Graves (1980), Yeats’s Interactions with Tradition (1987), Terrible Beauty: Yeats, Joyce, Ireland and the Myth of the Devouring Female (1988), Coleridge’s Submerged Politics (1994), Emerson, Romanticism, and Intuitive Reason: The Transatlantic “Light of All Our Day” (2003), and Emily Dickinson’s Approving God: Divine Design and the Problem of Suffering (2007).