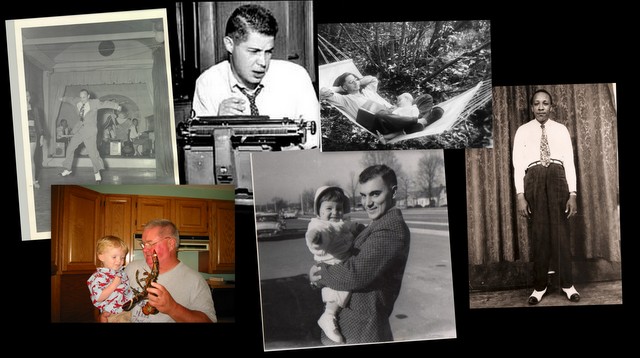

Fathers

Numéro Cinq’s growing collection of father pieces — essays, memoirs, poems, short stories, and, yes, music. Contributions from Keith Maillard, Byrna Barclay, Sophfronia Scott, Richard Farrell, Naton Leslie, Diane Moser, Natalia Sarkissian, Bunkong Tuon, Steven Axelrod and David Carpenter.

—

Talking to Brink was as close I was going to get to talking to Gene, and it badly shook me. For days afterward, I woke up feeling not right—a particularly nasty variety of not-right that was like waking up sickened by the stench of bad breath and realizing that it’s your own. I felt as though I had received a message directly from my father—one that predated the “fuck you” he’d sent me in his will when he’d disinherited me. If I was going to continue the conversation, what was I going to say back to him? I’m sorry about the surly letter I wrote to you when I was twenty? Gene would have been sixty-one when he got it—if he got it. He was still working at Hanford then. He might have talked to Brink about it. I hated the thought, but maybe that had been my only chance to connect with my father.

.White Shirts — Sophfronia Scott

Lena was born in 1917. My father, by then deceased, had come into the world in 1919 so I had grown up with her language, with her references. Talking to her was not that different from talking to my own father in our living room as he used to sit in his recliner. In fact Lena asked me about “my people” and I told her about my father coming from Mississippi and my mother’s family from Tennessee, and how they merged in Ohio but raised me and my siblings as though no one had ever left either of those southern spaces, right down to my father’s whippings and demeaning words that stung even more than the physical strikes. My sisters and I were taught to cook and clean and iron as if they were the only endeavors that could ensure our survival as women. By the time I was 18 and leaving for college I was so angry I vowed never to return. I didn’t tell Lena that part.

/On Fathers, Losses, and Other Influences — Bunkong Tuon

My father is mythic in my writing. He is clearly someone I’m not: a “gangster” with a sense of adventure, a man’s man who can hold his liquor and charm his way out of troubles with “good looks and easy talk.” The truth is: I never knew my father. He passed away in Cambodia in the 1980s, while I was a high school student in Malden, MA. When my grandmother, uncles, and aunts left for the UN camps along the Thailand-Cambodia border in 1979, my father decided to stay in Cambodia with his new family. Like many other Cambodians who had fallen victim to Pol Pot, his wife, my mother, had passed away from sickness and starvation under the Khmer Rouge regime in 1976 or so. My father took another wife several years later, when Vietnamese forces liberated Cambodia. Fearful that, as a stepson, I might be mistreated by my new family, my grandmother took me away from my father, carrying me on her back as she and her children trekked across the border, avoiding landmines and jungle pirates, to where the UN had set up a camp, rumored to have an abundance of food and medicine.

Getting Carried Away — David Carpenter

I was thinking about my father, the man who taught me to fish, but who never made time for himself to learn flyfishing. He had taken me and my friend Hyndman fishing on many occasions when he might more happily have lazed around the back yard, resting from his labours. Now he was an old man living with his wife far from the prairie of his youth, and unaware of this hairbrained scheme cooked up by my girlfriend and me. My father, who didn’t die after all. I was thinking that this moment by the creek, with the sound of Honor’s camera reminding me of another camera from many years ago, was an appropriate ending to our story.

Missing Dad — Natalia Sarkissian

I can say I lost my father when I was six. That was the year my parents separated. Although they weren’t divorced until a year or so later, I never spent long chunks of time with him after. I traveled from New York to Morgantown and later to Texas to visit him at Christmas and for two weeks every summer, but I was a kid. Instead of asking questions about his childhood (he grew up in Tehran, the son of well-to-do Russian émigrés) or his work (he was a professor of genetics), I roller skated in the driveway, swam in the pool at the complex or played Barbies in the bedroom with Rhonda, the girl next door. I didn’t know then that illness would cut his promising career and life short. And he never worried me with the fleeting nature of time.

Bigger Than Life — Naton Leslie

This is about the movies. My father swept the movie theater floor for the change he’d find, and for a free ticket to the next show. Then he’d see Flash Gordon, the news from The War, Roosevelt relaxed in his seat, shaking hands with other men my father called great, or, if he was lucky, white-hatted men who finally gunned down their black-hatted foes—simple justice, simple myth-making when there was a real enemy, when there was a right and a wrong, a drunk and sober, a dirty and clean, a hungry and full, a happy and sad. On this he was adamant. His days were times of extremes, delineated like black and white film, not muddy and imperfect and phony, with our life-like living color. It was damned shame, he’d say, the way things turned out.

For My Father | The Journey Home: Music In Remembrance — Diane Moser

When my father died, I decided to try again the musical cryptogram and add two of his favorite songs, “Deep River,” a traditional spiritual that he used to sing with his sister, and “My Buddy,” which was a special piece of music for him and his friends from WWII. The piece begins with the same idea of assigning notes to his name but with a pedal point (repeated note) and lots of open space for improvisation. I continue that pedal point with a free flowing rendition of “Deep River” and then let go of it as I play “My Buddy.” This piece was originally recorded with only piano and drums. I had wanted Mary Redhouse to be on the recording session, but it didn’t work out for that day. Two years later, she was on the east coast, and we recorded her, over dubbing twice while listening to the previous recording. Mary is a virtuoso vocalist and sings with Native American flute player R. Carlos Nakai, a favorite of my father’s. I especially love the hawk sounds by Mary at the end of this track; I can imagine my father ‘s soul flying over the Grand Canyon, one of his favorite places.

Into the Realm of the Dark — Richard Farrell

Our ritual of repeating lines can be maddening at times, but it also acts as a salve. Decades ago, when we watched the movies we now quote, they were happier times, before my parents split up, while my dad was still young and athletic and the future still hopeful. What has passed in the intervening years is simply life: pain, sorrow, estrangement, divorce, death—happy things, too, but far less comedic than what we must have expected that day. What we share now, what we hold like some sort of tentative cease-fire, is a mise-en-scène dialectic. Our conversations are heavily scripted. There is hardly an ad-libbed line anymore. We have developed an unwavering system of keeping the peace, of never dredging too deep. I work as hard at it as he does, never leading the scene astray. When it gets too heavy, too emotional, when it teeters on the edge, like it is now, we go back to the cue cards.

Red is the Colour of Mourning: Father Poems — Byrna Barclay

I made up the story. The King of the Dead Sea

looked like my father & rode a seahorse out of clouds,

twirling a seaweed rope that turned into a ladder

to save trapped in the turret of the castle school

a pigtailed child who looked too much like me.

My father always had faith in his own talent. He never had much beyond it to trust. His grandfather was a tyrant, his father was a tyrant’s prey who gave up his own career in show business under the threat of disinheritance. His grandfather, Jacob Axelrod, was the son of a Silesian rabbi, a Tzadic of the Hasidim, and Jacob was next in line. He fled that responsibility and arrived at Ellis island with fifty cents in his pocket. But of course he also had the steel to stand up to the absolute ruler of his fiercely insular religious sect, the arrogance to defy his father and the courage to sail away into the unknown, owning nothing and knowing no one. Fifty years later he was a different kind of king – a real estate maven who had bought and sold dizzying amounts of property in lower Manhattan. No one knows quite how he did it; or why, ten years later, he threw himself off the roof of one of his own buildings.

My father said his life started at nineteen, the moment he decided to join the Navy. On a muggy August afternoon, he was sharing a bottle of Jack Daniels on a porch with a guy everyone called Bud. About halfway down the bottle my father blurted out, “Let’s go join the Navy.” They roared down the country roads in my father’s 60’s Datsun truck with holes in the floorboard, over the low hills of houses and trees where there are no dogs – only hounds, between the square plots of soybean and cotton, and into town to the recruiting office.

Like this collection. Would like to contribute a piece. What’s the process? Thanks, Susan

I think my own father must have lived in the world described by Naton Leslie–though playfully. See below:

The car swept into the next valley with headlights glimmering off the ghostly trees and fence posts. I could hear cicadas droning out the windows, giving off their evening incantation. I could see lightning bugs pooled in a pasture, creating a big eddy of incandescence. I wanted to join all this magic, to rise right up with the hills and float away. “Faster, faster,” I called as the car climbed another hillside. And my father seemed to understand, gunning the engine. Mom protested in a way that suggested she was getting worried. “How much are speeding tickets?” she asked. But Dad was in the right mood now and shot us skyward at more than seventy miles an hour, risking maybe even $50. When we crowned the hilltop, the car took flight as if leaving a ramp, as if he could pilot us right out into the Milky Way. Only six or seven, I floated up there, looking out the windshield at the clustering stars—the sparkling dipper and the bright belt and all the other stars singing their come-on-up song—and I could feel myself getting closer. This time, I hoped, we would never come down.