Jacqueline Kharouf writes speculative fiction (mermaid lovers, robotic daughters, demonic violins) which in many ways is a lot like other fiction (as in, it’s all a lie anyway) except that in speculative fiction the author has to pay special attention to those aspects of craft having to do with convincing the reader to enter and live inside a fictional world quite unlike the one we inhabit normally. It’s one thing to tell a reader that “Arthur staggered out of the bar and leaped into his red convertible Mustang and drove across town to see his lover, Gertrude” and something else to write that “Arthur staggered out of the bar and leaped into his anti-gravitron photon streamliner and instantaneously reappeared across town in Gertrude’s apartment.”

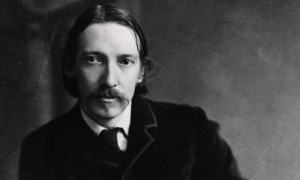

Jacqueline was my student last semester at Vermont College of Fine Arts. She took on the problem of convincing the reader for her critical thesis. She read Yevgeny Zamyatin’s novel We, Robert Louis Stevenson’s Dr. Jekyll and Mr. Hyde, and Angela Carter’s short story “The Company of Wolves” and plundered them for techniques she could use. The result is a useful compendium of devices for establishing the world of a story or a novel of any sort, not just speculative works. You will note, for example, the technique of the pre-story touched on in an earlier essay on Numéro Cinq in, Gwen Mullin’s “Plot Structure in Stories.”

Jacqueline earlier contributed a fine interview with Nick Arvin to the pages of NC. She also drew the illustrations for this essay.

dg

§

Every story takes place in its own fictive reality, which is an exaggeration of the reality of the real world. All writers write to create a literary reality that appears to be plausible, true or real within its own parameters. Verisimilitude is the word we use for the literary quality of appearing to be real. Writers strive for verisimilitude, that is, they try to make the fictive worlds of their stories seem plausible enough that the reader can suspend his or her doubts and trust the story. This trust is a bit like the trust we have in the world we live in, the so-called “real world,” which we experience in the details we observe, in the rules and societal expectations we follow, in the documentation we read, and in the experts who share their knowledge with us.

Writers use several techniques to create verisimilitude. These techniques mimic the ways we experience the real world.

The first technique I want to talk about is the use of false documents. A false document is a fictional document presented in a text as if it were real in the context of the fictional world. False documents, like documents in the real world, seem to authenticate the fictive world. In the real world, we learn about current events and information by reading authoritative sources. In a fictional text, false documents function much the way authoritative sources function in the real world, as more or less objective evidence of facts about that world. Also false documents seem to be free of narrative bias; they are outside the point of view of the narrating voice.

A second technique is the use of detailed concrete descriptions to make the fictive world of any story seem realistic and familiar. The more detailed the description of a world (up to the point of tedium) the more substantial and real that world seems. Realistic writers use such techniques to establish a relationship between their works and the real world; speculative writers use the same technique, or mimic it, to give the sense of a reality that may in fact not be so real.

A third technique is the framing of the fictive world of a story through the perspective of an authoritative narrator. An authoritative narrator is a reliable witness to the events of the story. In the real world, we seek the advice of authorities who provide their perspectives and knowledge. In an imaginary fictive world, an authoritative narrator acts as a filter for the reader’s perspective and influences the reader’s acceptance of the verisimilitude of that world.

A fourth technique is to use a literary reference as a parallel for a retold story, or conversely, to retell the literary reference in a new way. The reader accepts the fictive world of the new story because he or she is already familiar with the fictive world of the original story. Familiarity is, of course, one of the things we expect from the real world.

A fifth technique is the pre-story. A pre-story is a small story which precedes the main story or plot. Writers use pre-stories to introduce the reader to the world of the story and to illustrate the source of the conflict or incongruity which spurs the story forward. In the way that we use examples of similar incidents or events to preface a larger story we want to tell, pre-stories in literature help to underscore the larger conflict of the main plot. Or they function as ways of delivering thematic material that underpins the consistency of the fictive world.

Finally, a sixth technique is the repetition of key words, images, and phrases. Writers use repetition to create a consistent fictive world. Just as repeated events, images, and colloquialisms make the real world familiar, repetition creates consistency which the reader recognizes and identifies as familiar aspects of the fictive world.

.

.

Buried Under Glass: The Science Fictional World of Yevgeny Zamyatin’s We

Yevgeny Zamyatin’s We is a two-hundred page novel organized into 40 numbered records written by D-503, a man who lives in this fictive world. In these records, D-503 describes his life in the One State, the events of the story as they happen, as well as his thoughts, dreams, and feelings. The One State is a society composed of people who live according to the idea that happiness is a matter of following a regular and systematic schedule, conforming to rules which are applied equally to everyone, and ignoring individuality for the safety and stability of living as part of a group. While citizens of a nation like the United States believe that freedom is the ability to live as we choose, citizens of the One State believe that freedom is the ability to live according to rules which all members of society follow.

D-503 begins his first record (and the novel) by copying an article from the State Gazette. The article briefly explains the purpose of the Integral, the One State’s newest machine, and calls all so-called ciphers (or citizens of the One State) to compose written accounts of life in the One State. The One State will include these written accounts in the cargo of the Integral, a spaceship which will spread the clockwork-precise methodology of the One State to millions of alien societies across the cosmos. One day, D-503, the Builder of the Integral, meets I-330, a woman who seduces him and garners his devotion. She tells him she is planning to disrupt the control of the One State by stealing the Integral during its inaugural flight. D-503 agrees to this plan, but the mission fails.

D-503 begins his first record (and the novel) by copying an article from the State Gazette. The article briefly explains the purpose of the Integral, the One State’s newest machine, and calls all so-called ciphers (or citizens of the One State) to compose written accounts of life in the One State. The One State will include these written accounts in the cargo of the Integral, a spaceship which will spread the clockwork-precise methodology of the One State to millions of alien societies across the cosmos. One day, D-503, the Builder of the Integral, meets I-330, a woman who seduces him and garners his devotion. She tells him she is planning to disrupt the control of the One State by stealing the Integral during its inaugural flight. D-503 agrees to this plan, but the mission fails.

In the wake of several threats to the supreme power of the One State, the One State issues a new mandate that all ciphers must participate in an operation to have their imaginations removed. D-503 attempts to avoid this operation, but the authorities of the One State catch him and take him for the operation. With his imagination erased, and his soul removed, D-503 feels restored to his former state of bliss. At the conclusion of his records, D-503 watches while the Benefactor, the leader of the One State, tortures I-330 and sentences her to death.

False Documents and Double False Documents

Zamyatin uses false documents, which are documents “created” in the One State, to verify the events of the story and to provide information about the fictive world. The entire novel is a false document because it is a collection of false records written by D-503 (he titles his records “We”).

For example, before I-330 and D-503 attempt to steal the Integral, I-330 plans to disrupt the power of the One State on the Day of the One Vote. On this day, ciphers are supposed to vote unanimously to renew the leadership of the Benefactor, but I-330 and several other ciphers vote against the supreme leader. In Record 25, D-503 describes the vote and the aftermath:

In the hundredth part of a second, the hairspring of a clock, I saw: thousands of hands wave up—“No”—and fall again. I saw I-330’s pale face, marked with a cross and her raised hand. My vision darkened.

Another hairspring; a pause; a pulse. Then—as though signaled by some sort of crazy conductor—the whole tribune gave out a crackle, screams. A whirlwind of soaring unifs on the run, the figures of the Guardians rushing about in panic, someone’s heels in the air in front of my very eyes, and, next to the heels, someone’s wide-open mouth, bellowing an inaudible scream. For some reason, this cut into me more sharply than anything else; thousands of soundlessly howling mouths, as though on a monstrous movie screen.

The next day, the One State prints an article in the State Gazette denying the effectiveness of I-330’s planned protest. D-503 copies this article in Record 26:

Yesterday, the long and impatiently awaited Day of the One Vote took place. For the 48th time the Benefactor, who has proven His unshakable wisdom many times over, was unanimously chosen. The celebration was clouded by a slight disturbance wrought by the enemies of happiness, which, naturally, deprives them of the right to become bricks in the foundations of the One State, renewed yesterday.

This newspaper article is what we might call a double false document because it is a false document quoted within a false document (D-503’s record). Throughout the novel, D-503 copies double false documents, such as newspaper articles printed by the State Gazette, letters from other characters, or snippets of State poetry. These double false documents provide evidence of the growing split between D-503’s own experience of the world and the official version of the world. In a sense this is the story arc of the novel. D-503 begins writing his records and gradually finds his written version is different from the official version. But at the end of the novel he has again lost his ability to separate his personal experience from the official version.

D-503’s records enhance the verisimilitude of the novel; such diaries, newspaper articles, etc. are “firsthand” accounts. In this case, through the use of double false documents, Zamyatin even mimics the real-world split between personal and official versions.

Details

Zamyatin uses specific or concrete details to enhance the verisimilitude of the One State by creating the sense of a total consistent environment.

Ciphers depend on machines. In one of the 1,500 auditoriums where ciphers regularly attend lectures, a machine called a “phonolector” gives the presentation. When D-503 was younger and went to school, he was taught by a mathematics machine teacher that the students called Pliapa (because of the sound the machine made when it was turned on). To make music, ciphers in the One State use a musicometer (using it, a cipher can make three sonatas an hour). Later, at the Celebration of Justice, the ciphers sacrifice one of their own in tribute to the supreme rule of the Benefactor. To sacrifice the cipher, the Benefactor uses “the Machine,” an execution device:

An immeasurable second. The hand, applying the current, descends. The unbearably sharp blade of a beam flashes, then a barely audible crack—like a tremor—in the pipes of the Machine. A prostrate body—suffused in a faint luminescent smoke—melting, melting, dissolving with horrifying quickness before our eyes.

By inserting details about each of these machines—the pliapa sound, the cracks and flashes, the pipes, the color of the smoke—Zamyatin gives a sense of the concrete experience of the fictive world of the One State.

Zamyatin also includes details about the ciphers; the same details are repeated throughout the story to make the lives of these ciphers consistent. Consistency is, of course, a characteristic of the so-called real world we live in, but in this novel consistency has an edge; the One State requires a super-consistency from its inhabitants. Ciphers wear the same clothes, gold badges and time pieces: “Hundreds and thousands of ciphers, in pale bluish unifs, with gold badges on their chests, indicating the state-given digits of each male and female.” All ciphers shave their heads: “Circular rows of noble, spherical, smoothly sheared heads.” Every cipher wakes at the same exact time:

The small, bright, crystal bell in the bed’s headboard rings: 07:00. It’s time to get up. On the right, on the left, through the glass walls, it’s as if I am seeing myself, my room, my nightshirt, my motions, repeating themselves a thousand time. This cheers me up: one sees oneself as part of an enormous, powerful unit. And such precise beauty: not one extraneous gesture, twist, or turn.

Everyday, they sing the Hymn of the One State after breakfast: “Breakfast was over. The Hymn of the One State had been sung harmoniously.” (31). In groups of four, everyone marches to work: “In fours, we went to the elevators, harmoniously. The rustling of the motors was almost audible—and rapidly down, down, down—with a slight sinking of the heart…” The sensory details of the rustling elevator motors and the “sinking of the heart,” as well as the everyday familiarity of their harmonious movements, are concrete experiential details which make the One State seem like a real place.

.

.

Uncanny Duplicity and Scientific Perversion: The Metaphysical Worldview in The Strange Case of Dr. Jekyll and Mr. Hyde by Robert Louis Stevenson

Stevenson separates his short novel into three sections. For the first (and largest) portion of the novel, Stevenson divides the narrative into eight chapters and describes the main plot from the third-person perspective of Mr. Utterson, a lawyer. In the second portion of the novel, “Dr. Lanyon’s Narrative,” Stevenson provides the first-person perspective of Dr. Lanyon, a friend of Utterson and Dr. Jekyll. In the third portion of the novel, “Henry Jekyll’s Full Statement of the Case,” Stevenson writes a narrative from the first-person perspective of Dr. Jekyll, who provides his side of the story. The novel takes place in nineteenth century London. Stevenson’s London is like the real London of that century (the descriptions of the city seem to resemble what London may have looked like in that time in history), but it is different because the London of the novel is plagued by the heinous criminal activity of a man who slips in and out of society. The mystery of this man’s identity, his origins, and his connection to Dr. Jekyll affects the world of the novel and drives the action of the plot.

Stevenson separates his short novel into three sections. For the first (and largest) portion of the novel, Stevenson divides the narrative into eight chapters and describes the main plot from the third-person perspective of Mr. Utterson, a lawyer. In the second portion of the novel, “Dr. Lanyon’s Narrative,” Stevenson provides the first-person perspective of Dr. Lanyon, a friend of Utterson and Dr. Jekyll. In the third portion of the novel, “Henry Jekyll’s Full Statement of the Case,” Stevenson writes a narrative from the first-person perspective of Dr. Jekyll, who provides his side of the story. The novel takes place in nineteenth century London. Stevenson’s London is like the real London of that century (the descriptions of the city seem to resemble what London may have looked like in that time in history), but it is different because the London of the novel is plagued by the heinous criminal activity of a man who slips in and out of society. The mystery of this man’s identity, his origins, and his connection to Dr. Jekyll affects the world of the novel and drives the action of the plot.

The novel text begins with Utterson’s narrative. Utterson is worried about Dr. Jekyll’s will. Utterson has learned that Jekyll has recently changed his will to name Mr. Hyde as his heir despite Mr. Hyde’s poor reputation. After Mr. Hyde commits several crimes and Jekyll avoids meeting his friends, Utterson confronts Jekyll. Utterson and Poole, Jekyll’s butler, break into Dr. Jekyll’s study, but they only find Mr. Hyde’s body and a sealed letter from Dr. Jekyll addressed to Utterson.

Then, in “Dr. Lanyon’s Narrative,” Lanyon gives an account of Jekyll’s strange behavior on the night he received a letter from Jekyll and witnessed Mr. Hyde transform into Dr. Jekyll.

Finally, the novel concludes with “Henry Jekyll’s Full Statement of the Case,” which is the sealed letter Utterson found with Hyde’s body. In his statement, Jekyll provides personal testimony of his scientific experiment on his own dual-sided nature. Jekyll explains that by drinking a concoction of several distilled chemicals and salts he could transform into Mr. Hyde, the embodiment of Jekyll’s worst qualities. The more often Jekyll drank his chemical potion, the less easily he could resume his Jekyll-form. In his final sentences, Jekyll explains that because he cannot correct his mistake and resume his normal form, he will kill himself.

Authoritative Narrator

An authoritative narrator is a narrator who provides a reliable perspective on the story. In the case of Stevenson’s novel, Mr. Utterson, a lawyer, is an intelligent, common-sensical, and reliable witness attempting to understand and relay what is happening.

Utterson first learns about Hyde from Mr. Enfield, who describes the night he saw Hyde trample a child in the street. Utterson questions his friend’s information:

Mr. Utterson again walked some way in silence, and obviously under a weight of consideration. “You are sure he used a key?” he inquired at last.

“My dear sir….” began Enfield, surprised out of himself.

“Yes, I know,” said Utterson; “I know it must seem strange. The fact is, if I do not ask you the name of the other party, it is because I know it already. You see, Richard, your tale has gone home. If you have been inexact in any point, you had better correct it.

Enfield’s information about Hyde alarms Utterson and he returns home to study Dr. Jekyll’s will:

The will was holograph; for Mr. Utterson, though he took charge of it now that it was made, had refused to lend the least assistance in the making of it; it provided not only that, in case of the decease of Henry Jekyll, M.D., D.C.L., L.L.D., F.R.S., &c., all his possessions were to pass into the hands of his “friend and benefactor Edward Hyde”; but that in case of Dr. Jekyll’s “disappearance or unexplained absence for any period exceeding three calendar months,” the said Edward Hyde should step into the said Henry Jekyll’s shoes without further delay, and free from any burthen or obligation, beyond the payment of a few small sums to the members of the doctor’s household. This document had long been the lawyer’s eyesore. It offended him both as a lawyer and as a lover of the sane and customary sides of life, to whom the fanciful was the immodest. And hitherto it was his ignorance of Mr. Hyde that had swelled his indignation; now, by a sudden turn, it was his knowledge. It was already bad enough when the name was but a name of which he could learn no more. It was worse when it began to be clothed upon with detestable attributes; and out of the shifting, insubstantial mists that had so long baffled his eye, there leaped up the sudden, definite presentment of a fiend.

From this moment on, Utterson, our authoritative narrator, collects more information in order to build his “case” on the true nature and intentions of Mr. Hyde. For example, after the murder of Sir Danvers Carew (one of Mr. Utterson’s clients), the police contact Utterson because they found a letter addressed to Utterson in Carew’s purse. Utterson identifies the body and a police officer tells him that a maid witnessed Mr. Hyde beat the old man to death with a walking stick: “Mr. Utterson had already quailed at the name of Hyde; but when the stick was laid before him, he could doubt no longer: broken and battered as it was, he recognized it for one that he had himself presented many years before to Henry Jekyll.”

As Utterson becomes more engrossed in understanding the strangeness of the connection between Jekyll and Hyde, his belief in the witnesses and information of the fictive world persuades the reader to accept that strangeness, too.

False Documents

Stevenson uses the same false document technique as Zamyatin, and in Stevenson’s novel, just as in We, false documents seem to authenticate the world of the story. In Utterson’s narrative, Stevenson quotes correspondence and documents supplied by other characters. At the end of Utterson’s narrative, Stevenson also includes personal testimony and sealed letters from both Dr. Lanyon and Dr. Jekyll; these comprise the second and third parts of the novel which corroborate Utterson’s investigation.

For example, toward the conclusion of Utterson’s narrative, he quotes a note Jekyll had written to obtain more of his chemical supplies. Jekyll’s butler Poole shows Utterson the note because it is evidence of Jekyll’s increasingly strange behavior. This note is a double false document:

Dr. Jekyll presents his compliments to Messrs. Maw. He assures them that their last sample is impure and quite useless for his present purpose. In the year 18—, Dr. J. purchased a somewhat large quantity from Messrs. M. He now begs them to search with the most sedulous care, and should any of the same quality be left, to forward it to him at once. Expense is no consideration. The importance of this to Dr. J. can hardly be exaggerated.

Utterson doesn’t learn the full circumstances of Jekyll’s seclusion, however, until Stevenson supplies further explanations from the false documents of Dr. Lanyon and Dr. Jekyll.

In the second part of the novel, Dr. Lanyon witnesses Hyde transform into Dr. Jekyll and pens his reaction: “What he told me in the next hour I cannot bring my mind to set on paper. I saw what I saw, I heard what I heard, and my soul sickened at it; and yet, now when that sight has faded from my eyes, I ask myself if I believe it, and I cannot answer.” Lanyon does not explain how this transformation happened, but his claim that he “saw what he saw” and “heard what he heard” establishes an experiential authenticity for the strange event.

The reader doesn’t fully understand what has happened to Jekyll until Jekyll explains in his false document which is the third part of the novel. In this part, Jekyll describes why he did his experiments, briefly summarizes his theory behind his invention, and shares the sense of freedom his experiment gave him, as well as its drawbacks. Jekyll’s letter has a special air of authenticity because it appears to answer questions asked and left unanswered in the previous accounts. The letter has a dramatic impact that enhances its contribution to the verisimilitude of the novel.

I was born in the year 18— to a large fortune endowed besides with excellent parts, inclined by nature to industry, found of the respect of the wise and good among my fellow men, and thus, as might have been supposed, with every guarantee of an honorable and distinguished future. And indeed, the worst of my faults was a certain impatient gaiety of disposition, such as has made the happiness of many, but such as I found it hard to reconcile with my imperious desire to carry my head high, and wear a more than commonly grave countenance before the public. Hence it came about that I concealed my pleasures; and that when I reached years of reflection, and began to look round me and take stock of my progress and position in the world, I stood already committed to a profound duplicity in life.

Jekyll’s apparently sound emotional judgement, his ability to see his faults, make his account seem real and possible in this fictive world.

Lanyon’s visceral reaction to Jekyll’s metamorphosis authenticates the strangeness of the event. Jekyll’s honesty regarding his own mistakes rings true and this, along with Stevenson’s other false documentation, encourages the reader to accept his explanation of events.

Details

Stevenson also uses the concrete sensory details technique to make Jekyll’s transformation seem plausible. For example, in his letter to Utterson, Dr. Lanyon provides physical details of Jekyll’s transformation:

He put the glass to his lips, and drank at one gulp. A cry followed; he reeled, staggered, clutched at the table and held on, staring with injected eyes, gasping with open mouth; and as I looked, there came, I thought a change—he seemed to swell—his face became suddenly black, and the features seemed to melt and alter—and the next moment I had sprung to my feet and leaped back against the wall, my arm raised to shield me from that prodigy, my mind submerged in terror.

Lanyon’s detailed experience of what happened persuades the reader to accept the plausibility of a fictive world where such a transformation is possible.

Stevenson also provides details of the chemical potion which Jekyll concocts. Stevenson is not specific on Jekyll’s exact recipe, but the potion’s power seems believable because Stevenson provides the same details from two authoritative medical sources. Lanyon, who explicitly declares he’s not interested in metaphysical experiments, first describes these details in his letter—again in concrete experiential terms:

The powders were neatly enough made up, but not with the nicety of the dispensing chemist; so that it was plain they were of Jekyll’s private manufacture; and when I opened one of the wrappers, I found what seemed to me a simple crystalline salt of a white color. The phial, to which I next turned by attention, might have been about half-full of a blood-red liquor, which was highly pungent to the sense of smell, and seemed to me to contain phosphorus and some volatile ether.

Jekyll describes his ingredients in his letter:

I had long since prepared my tincture; I purchased at once, from a firm of wholesale chemists, a large quantity of a particular salt, which I knew, from my experiments, to be the last ingredient required; and, late, one accursed night, I compounded the elements, watched them boil and smoke together in the glass, and when the ebullition had subsided, with a strong glow of courage, drank off the potion.

Lanyon’s staunch opposition to metaphysics supports the credibility of his observations just as Jekyll’s level-headed description, including the purchase of elements, also creates a sense of plausibility. The details—little half-hints that boiling a few well-mixed ingredients will coalesce into a substance which can melt away one self and replace it with another—lends credibility to Jekyll’s metaphysical experiment.

.

.

Red, Green, Gray, Howl: The Magical World of Angela Carter’s Short Story “The Company of Wolves”

Angela Carter’s short story “The Company of Wolves” is a contemporary reworking of the folk tale “Little Red Riding Hood.” Carter structures the story in two parts. In the first part, she introduces the world of her story with a series of pre-stories and lore about wolves and werewolves. In the second part, she tells the story of a young woman who goes to visit her grandmother and encounters a werewolf along the way.

A fter the section of lore and pre-stories, the main story of “The Company of Wolves” begins with a teenage girl in a red shawl walking through the woods to visit her grandmother. She carries a knife and stays to the path so that she won’t get lost or fall into the clutches of the wolves. Along the way, she flirts with a hunter, who runs ahead to her grandmother’s house where he transforms into a wolf and eats the grandmother. The girl arrives, knocks, and hearing the werewolf mimicking her grandma’s voice, thinks it is safe to enter. The werewolf jumps up and slams the door behind her. The girl undresses and throws her clothes in the fire because the werewolf tells her she won’t need them anymore. But she defeats the werewolf by throwing his clothes in the fire, too. According to the lore of the story, without his human clothes, the werewolf is magically condemned to stay in his wolf-shape. The story ends with the girl and the wolf together in a very strange sort of marriage.

fter the section of lore and pre-stories, the main story of “The Company of Wolves” begins with a teenage girl in a red shawl walking through the woods to visit her grandmother. She carries a knife and stays to the path so that she won’t get lost or fall into the clutches of the wolves. Along the way, she flirts with a hunter, who runs ahead to her grandmother’s house where he transforms into a wolf and eats the grandmother. The girl arrives, knocks, and hearing the werewolf mimicking her grandma’s voice, thinks it is safe to enter. The werewolf jumps up and slams the door behind her. The girl undresses and throws her clothes in the fire because the werewolf tells her she won’t need them anymore. But she defeats the werewolf by throwing his clothes in the fire, too. According to the lore of the story, without his human clothes, the werewolf is magically condemned to stay in his wolf-shape. The story ends with the girl and the wolf together in a very strange sort of marriage.

Literary Reference as Parallel

Carter uses a literary reference as the basis for the plot of “The Company of Wolves.” The familiarity of the original plot helps to create the fictive world of Carter’s story, which is similar but deviates from the original folktale (which is not about sex or werewolves and in which the wolf eats the girl). In place of the big, bad, cunning wolf who gorges on human flesh, Carter invents a green-clad hunter who, though charming at first, transforms into a wolf and devours the grandmother. Just like Little Red Riding Hood, the girl of Carter’s story is determined to visit her grandmother, but when she discovers the wolf-man in her grandmother’s place, the girl of Carter’s story is not so naive or unobservant. Rather than falling prey to the wolf’s cunning, Carter’s heroine defeats the werewolf by condemning him to be a wolf for the rest of his life.

By referring to the plot, characters, and even dialogue of the original fable, Carter draws parallels between the two texts. As we read, we contrast Carter’s story with the original. We anticipate what will happen next based on our reading of the original story. Carter subtly subverts these expectations by adding surprising new elements and twists of plot.

Pre-Stories

Before beginning the main plot of the story, Carter tells three pre-stories, anecdotes that precede the main plot in the text. These stories tell about the interactions between humans and werewolves. Here is an example.

There was a hunter once, near here, that trapped a wolf in a pit. This wolf had massacred the sheep and goats; eaten up a mad old man who used to live by himself in a hut halfway up the mountain and sing to Jesus all day; pounced on a girl looking after the sheep, but she made such a commotion that men came with rifles and scared him away and tried to track him to the forest but he was cunning and easily gave them the slip. So this hunter dug a pit and put a duck in it, for bait, all alive-oh; and he covered the pit with straw smeared with wolf dung. Quack, quack! Went the duck and a wolf came slinking out of the forest, a big one, a heavy one, he weighed as much as a grown man and the straw gave way beneath him—into the pit he tumbled. The hunter jumped down after him, slit his throat, cut off all his paws for a trophy.

And then no wolf at all lay in front of the hunter but the bloody trunk of a man, headless, footless, dying, dead.

This story introduces the theme of the magical transformation of man to wolf and wolf to man plus the idea that humans are constantly fighting werewolf incursions. By creating the sense of a place where such transformations and conflicts are natural, Carter sets the stage for the story that follows. In the second pre-story, a witch turns people into wolves out of spite. She punishes the man who rejected her by making him the loneliest and most rejected creature in this fictive world. In the third pre-story, a woman marries a man who is taken by wolves and later transforms into a wolf after he learns that she married another man. The woman’s first husband turns into a wolf and attacks, but as he dies, he transforms back into the man he was before.

Carter intersperses other werewolf lore between the pre-stories. Later in the text, in the second half of the story, she refers back to this information. For instance, after the third pre-story, Carter supplies material about the birth, appearance and heart of the werewolf: “Or, that he was born feet first and had a wolf for his father and his torso is a man’s but his legs and genitals are a wolf’s. And he has a wolf’s heart.” Later, Carter reiterates this information in her description of the werewolf before he eats the grandmother: “He strips off his shirt. His skin is the color and texture of vellum. A crisp stripe of hair runs down his belly, his nipples are ripe and dark as poison fruit […] He strips off his trousers and she can see how hairy his legs are. His genitals, huge. Ah! huge.” Carter provides this lore to describe and validate the world of the story. And by repeating this information later, Carter builds consistency which helps to create the verisimilitude of that world.

Repetition

Carter uses repetition of images, words, and phrases to build a consistent fictive world. First, she creates a pattern of images of blood, the color red, and menses. For example, Carter initiates the pattern in a bit of backfill and description; the girl “had been indulged by her mother and the grandmother who’d knitted her the red shawl that, today, has the ominous if brilliant look of blood on snow,” and that, “her cheeks are an emblematic scarlet and white and she has just started her woman’s bleeding.” Carter repeats these images. For instance, when Red finds the werewolf at her grandmother’s house: “she shivered, in spite of the scarlet shawl she pulled more closely round herself as if it could protect her although it was as red as the blood she must spill.” The blood the girl “must spill” is both an indication of her menses (which she “must spill” each month henceforth) and a hint at the act she will perform to condemn the werewolf to his wolf-shape (she gives him her immaculate flesh). Finally, at the climax of the story, the werewolf bids her to take “off her scarlet shawl, the color of poppies, the color of sacrifices, the color of her menses.”

Carter also repeats references to the lore of wolves and werewolves. Carter supplies this information first, as I have mentioned, in her pre-stories. For instance, in the lore section, Carter describes the eyes of wolves: “…the pupils of their eyes fatten on darkness and catch the light from your lantern to flash it back to you—red for danger.” After the grandmother invites the hunter into her house, he is described as having “…eyes as red as a wound…” Later, his eyes are like “cinders” and then “saucers full of Greek fire, diabolic phosphorescence.” The moment the girl approaches the wolf-man, Carter describes him as “the man with red eyes.” (The red pattern here connects with the red pattern in the of blood, shawl and menses.)

Carter mentions the ribs of the wolves in winter: “There is so little flesh on them that you could count the starveling ribs through their pelts, if they gave you time before they pounced.” Later Granny notices the werewolf’s ribs, too: “…he’s so thin you could count the ribs under his skin if only he gave you the time.”

Carter describes the wolves’ howling three times in her opening paragraphs: “One beast and only one howls in the woods by night”; “…hark! his long, wavering howl…an aria of fear made audible”; “The wolfsong is the sound of the rending you will suffering, in itself a murdering.” The howling of the wolves serenades the witch in the second pre-story: “…they would sit and howl around her cottage for her, serenading her with their misery.” In the third pre-story, the woman hears the wolves howling after her first husband disappears: “Until she jumps up in bed and shrieks to hear a howling, coming on the wind from the forest.” According to the lore of Carter’s fictive world, the howling of the wolves is a mark of their melancholy:

That long-drawn, wavering howl has, for all its fearful resonance, some inherent sadness in it, as if the beasts would love to be less beastly if only they knew how and never cease to mourn their own condition. There is a vast melancholy in the canticles of the wolves, melancholy infinite as the forest, endless as these long nights of winter and yet that ghastly sadness, that mourning for their own, irremediable appetites, can never move the heart for not one phrase in it hints at the possibility of redemption; grace could not come to the wolf from its own despair, only through some external mediator, so that, sometimes, the beast will look as if he half welcomes the knife that dispatches him.

At the start of her journey through the woods, the girl hears a howl: “When she heard the freezing howl of a distant wolf, her practiced hand sprang to the handle of her knife…” When the girl enters her grandmother’s house only to find the hunter, she hears the wolves howling outside: “Now a great howling rose up all around them, near, very near as close as the kitchen garden, the howling of a multitude of wolves; she knew the worst wolves are hairy on the inside […] Who has come to sing us carols, she said.” The girl looks out the window:

It was a white night of moon and snow; the blizzard whirled round the gaunt, grey beasts who squatted on their haunches among the rows of winter cabbage, pointing their sharp snouts to the moon and howling as it their hearts would break. Ten wolves; twenty wolves—so many wolves she could not count them, howling in concert as if demented or deranged […] She closed the window on the wolves’ threnody.

And at the end of the story, the wolves serenade the “savage marriage ceremony” of the girl and the werewolf: “Every wolf in the world now howled a prothalamion outside the window as she freely gave him the kiss she owed him.”

Carter also repeats specific phrases to create an associative pattern. Like image and lore patterning, phrasal patterning makes the fictive world coherent and consistent because such repetition builds associations for the reader. For example, she repeats the phrase “carnivore incarnate” three times in the story. She describes the wolf in the second line of the story: “The wolf is carnivore incarnate and he’s as cunning as he is ferocious, once he’s had a taste of flesh then nothing else will do.” Carter uses the phrase again after the wolf-man eats the grandmother: “The wolf is carnivore incarnate.” Lastly, Carter uses “carnivore incarnate” when the girl defeats the werewolf: “Carnivore incarnate, only immaculate flesh appeases him.” Carter also repeats the title phrase “company of wolves” when the girl notices the wolves howling outside her grandmother’s house. The wolf-man explains: “Those are the voices of my brothers, darling; I love the company of wolves.”

Repetition of these phrases makes the world of the story meaningful because such phrases influence how the reader interprets and understands the world of the story. The wolf is such a danger to this world that it is essentially a “devouring deity” only pleased by immaculate flesh. By repeating images with the color red, lore about the features of wolves and werewolves, including red eyes, slavering jaws, ribs, and howling, and specific phrases, such as “carnivore incarnate” and the title, Carter builds a consistent and familiar fictive world. Repetition creates consistency which reinforces the verisimilitude of the world of the story.

— Text & illustrations by Jacqueline Kharouf

Works Cited

Carter, Angela. “The Company of Wolves.” Burning Your Boats, The Collected Short Stories. New York: Penguin, 1995. 212-220.

Stevenson, Robert Louis. The Strange Case of Dr. Jekyll and Mr. Hyde. New York: Pocket Books, 2005.

Zamyatin, Yevgeny. We. New York: Modern Library, 2006.

———————————-

Jacqueline Kharouf is currently studying for her MFA in creative writing, fiction, at the Vermont College of Fine Arts. A native of Rapid City, SD, Jacqueline lives, writes, and maintains daytime employment in Denver, CO. In 2009, she earned an honorable mention for the Denver Woman’s Press Club Unknown Writer’s Contest, and in 2010 she earned third place for that contest. Her first published story, “The Undiscoverable Higgs Boson,” was published in issue 4 of Otis Nebula, an online literary journal. Last year, Jacqueline won third place in H.O.W. Journal’s 2011 Fiction contest (judged by Mary Gaitskill) for her story “Seeing Makes Them Happy.” This story is currently available online and will be published in H.O.W. Journal’s Issue 9 sometime in the fall/winter of 2012. Jacqueline blogs at: jacquelinekharouf.wordpress.com; tweets holiday appropriate well-wishes and crazy awesome sentences here: @writejacqueline; and will perform a small jig if you like her Facebook professional page at: Jacqueline Kharouf, writer. She earlier contributed an interview with Nick Arvin to these pages.

This is great, Jacqueline. I have more to read, but what a terrific topic and detailed analysis. Thanks for sharing it here!