Childhood

.

A childhood is not a period of life and does not pass on.

It haunts discourse.

—Jean-François Lyotard

.

(Click the names for complete essays.)

He gripped my mouth with one hand, forcing me to breathe through my nose, while his other hand crept up my bare leg and into the bottom of my leotard. At first, his fingers tickled, making me feel warm and shivery, then they jabbed into my flesh, sending a sharp pain up through my whole body and into my head. I tried to scream again, tried to bite his hand, but it was pressed too tightly against my mouth.

I remember the day Joanie caught me alone in the big sunny kitchen in the Carolwood Drive house, all that blond hair, the long face, the spike nose and those intense brown eyes, looming over me. She could intimidate an attack dog. “You’re ten years old. It’s time you understood. Your father is an alcoholic.” She flensed me with the details of that caustic revelation: she covered for him with the studios, dried him out before meetings and indeed, her favorite interjection, had been making all the money in the family for years. The manic gusto, the sadistic glee on her face, terrified me.

At night I would sometimes sneak out and eat brown sugar from the bowl on the kitchen table and watch the woman across the way taking a bath. I got in trouble for things like that, getting out of bed, getting into mischief. They tied me in my crib when I was little. I don’t remember that, unless unconsciously, in my limbs, the occasional anxiety passing through. They told me about that later.

There was the house in Palo Alto that was all glass. A screenwriter’s house. Friends were staying there and invited us to visit for a couple of days. I had artichokes for the first time there. Dipped the leaves in melted butter, pulled them through my front teeth. They had two refrigerators, I remember, a richness that seemed incomparable at the time. They had a pool that was lit up blue at night, and the hot tub was red. We ran from floor to floor of this glass house watching our parents out in the hot tub, drinking champagne.

Even though I had long since learned that adults lie, even to children, it was like discovering it again. That memory had been buried under layers of years’ worth of other memories and experiences and lessons. So, when I saw her dingy frayed ponytail wagging and thin legs scrambling over the parking lot I was transported back in time, back when I was a little girl, back when I stayed inside the fence. The innocence returned to me as quickly as it was gone again and I felt the rawness of those first you-lied-to-me-now-I-can’t-trust-you situations and their attending hurt.

Escape artist, you look to Hollywood for familiar narratives, real and imaginary: Sixteen Candles, Pretty in Pink, The Breakfast Club. It’s the 80s – you listen to The Smiths, The Cure – and so for a time you are saved by the treacherous optimism of the cynic from certain side-tracks, seductions of the dreaming screen. You seek out copses of wood in the ravine, beside the fake lake, swamp of stolen bicycles, grocery buggies, plaid chesterfields, pizza boxes, condoms, cigarette butts and underpants, beer bottles, pop cans and PVC. You aren’t picky at that time and will accept pre-fabricated nature if that’s the best they can offer. Writing place: hiding place.

I hungered for books but books were scarce in our house. Though my mother appreciated the value of books, money was often too short to afford them and the nearest library an inconvenient eight miles away, in Loughrea. I made do for a long time with a huge tome called Flaming Flamingos that my uncle Mattie had brought. All of nature seemed contained in that book. The Camargue, Lake Nakuru, the Orinoco, that book whetted my hunger. It widened my thought even if I often got stuck in the mud of its ornithological intent. Over time it grew shabby and dog-eared and its spine broke. Finally someone must have fecked it into the fire while I wasn’t looking.

It is August 11, 1978. A humid morning succumbs to another blistering New England afternoon. Potbellied cumuli gather low on the horizon in an otherwise pristine cobalt sky. Colleen is twelve, three years my senior, an insurmountable chasm of days standing between us. I am already madly in love with her. She lives next door on Walter Street in Worcester, Massachusetts. For fifteen years, our bedroom windows will stare unblinkingly at one another across ten yards of space. Blue eyes (of course), a demure grin, tan legs, and a habit of staring straight through me when she speaks. From time to time, a tiny cluster of heat blisters forms on he lower lip like a welcoming galaxy

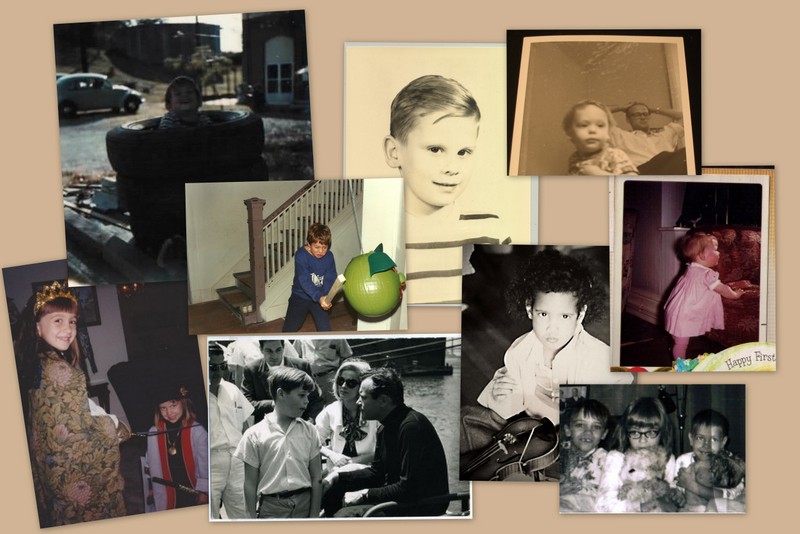

These pictures of my sister Kristen almost didn’t make it into the canon. They were taken after she had gone into the bathroom, aged three, and given herself a haircut. For years, Andrew and I used these images to tease her. She hated them, wanted them destroyed, at one point even stole them from the family album. I’m surprised they still exist. I’m glad they still exist, because in 1999, at the age of fourteen, Kristen died of meningitis, and our family’s narrative was irrevocably changed. After such an event, every trace of the past gains in significance.

Boil treatment started with my mother’s dreaded knee. I’d see that knee approach, the moonlight bulb of its bending, then her thigh, then her wide hips arcing like parentheses as she kneeled down, lowering her frantic face to mine. “Time to doctor your butt,” she’d say. “We don’t want infection.” I’d close my eyes, turn my face away, and breathe in the honeysuckle through the window. My mother was always concerned with infection, with bringing in something unknown from the outside that would damage us. Both of my parents—and the entire congregation to which we belonged—were fearful of the world and sought to insulate us all from the horror and wonder of a worldly life.

Horseshoes clank and thud in the dusty pits behind the beer-garden where old men play poker and drink an amber liquid from tiny glasses. Their cigars make a canopy of oaken smoke over a low hanging black walnut branch which shades the lichened table where they sit. Bright glints of afternoon light chink through the foliage here and again. Inside the crowded beer garden, nutshells crunch under your sandals, bigger kids push past you. Teenage girls, hips swathed in plaid peddle-pushers, sway rhythmically to the beat that rolls from the grill of the Seeburg juke box

When I’d first been learning to talk, Keith had been hard to say, so I had become Keats. That’s how I thought of myself, and for years that’s how I signed the cards I gave my mother and grandmother at Christmas and on their birthdays. While I was still inside that eternity of “not-in-school-yet,” I consumed comic books like peanuts, and the classic, iconic pop-culture images from the late Forties flowed into my own stories. Like Batman, I drove a sleek, murderously fast car jammed with amazing modern gadgets; mine was called “the Keatsmobile.”

This summer you are friends with the guy counselors. You kiss two of them, and on a motorcycle, put your arms around a third. The next year you will paste some of these very same baby pictures in a scrapbook for that boy. Your mother will be angry. You won’t even be going out with him in a year, she’ll say. You’ll show her. He will follow you to college. You will marry him. Then, cutting your losses, you will divorce him. But, as 1972 draws to a close, you don’t know any of that. You are stardust and golden.

With her fundamentalist mixture of Dave Martin Mennonite and Plymouth Brethren beliefs, fed by radio preachers like Theodore H. Epp, my mother thought that TV, movies, card-playing, and dancing were all worldly, if not sinful. We grew up believing that everyone around us was a heathen, headed for hell, intent on tempting us into lives of sin. We could play with neighbourhood kids, but we understood they were different than us, and we shouldn’t get too close to them (in the summer, my mother held Daily Vacation Bible Schools in our yard, in an effort to convert our friends).

The shack consisted of three tiny rooms, no indoor plumbing, no electricity. Slats showed through jagged cracks in the walls. Chunks of plaster were scattered pebbly on the warped floorboards. My father picked a chunk up, thumbed powder from the edges. “Luxury,” he said. “Thomas Aquinas wrote the Summa Theologica in a stone monk’s cell with a quill pen and a candle. Men like that have about gone the way of the gooney bird.”

…my grandmother’s talk was more than chatter in overdrive: it was conversation, for she was a woman who had things she wanted you to know. And yet, for all her intense need to convey this or that or the next hundred things, there was also a way I began to understand she was not exactly communicating, at least not in the hopeful sense of the word. For that was the other thing: when it came to my grandmother and her talk, I often had this sense of her standing back behind the flood of words as if behind a tree at a river, calculating what she intended, peering out from her shelter to gauge your response.

When my mother and her colleagues arrived at this stretch of road — the first members of the press on the scene after the bodies had lain untended for two hours — they dubbed it “The Street of Horror.” My parents were lovers at the time, and theirs was what you would call an unsanctioned relationship. I was born on April 1, 1973. If you count back exactly nine months from that date, you arrive at July 1, 1972, the same day the Song Than press members arrived and my mother and father stood together for a moment on that patch of Highway 1.

Years later, my sister and I and the girl from across the street put the pasture to another use. Hanging from a nail on our kitchen wall was a tin matchbox holder, and in it was a box of Eddy’s Redbirds. The tips of the matches were banded blue and red and white, the colours of the Union Jack. We’d grab them by the handful, couldn’t stop ourselves from licking them to taste the naughty taste. We’d make off with them to light our little fires. In the pasture we pulled together small, dense stooks of dry grass, lit them, and watched as they went poof, and flared and died. One day the flare didn’t die. We high-tailed it away and waited for a grown-up to notice the grass fire. Eventually, a grown-up did. The volunteer fire department came out in force to quell the flames, and we were either not found out or were silently excused without a fuss.

We lived on the hill. From our gate we could see far across the valley to the mountain. Everyone called it Terrible Billy though its real name was Mount Terrible. At the foot of the mountain was our town, Werris Creek, just three miles from home. At night we watched the lights sparkling, mainly street lights and those at the loco yards where steam locomotives shunted the freight cars. In summer I slept on the veranda. The night sky shimmered and I heard trains puffing slowly up the valley. (See also: An Australian Childhood: One Fine Day — Elizabeth Thomas and An Australian Childhood: What Ever Happened to Grace Darling? — Elizabeth Thomas.)

During the Universal Prayer, I sit in the hard wooden front pew, my mother’s unfailingly devout seating choice, squeezed between my older sister and brother. Each time Father Wilkening begins the series, I close my eyes and press my palms together beneath my chin, and pray. But in my selfish little eight-year-old heart, I don’t care about the Pope. I don’t care about peace with Russia. I don’t care about the sick. I care about the rain.

Is he your real father? People ask this rudely before I am old enough to understand. Yes, he is real from the time I am born, mopping his paint-splattered floor 17 times before my mother arrives home with me. He puts his name on me and my birth certificate so he will never be reduced to a step-father. At night he sings to me in a flat voice that is all gravel and we dance across the living room until I rub my eyes into his neck, fighting sleep. He has a sharp smell that hangs around him, a mix of turpentine for his work and peppermint candies for his indigestion.