http://wp.me/p1WuqK-kRQ

x

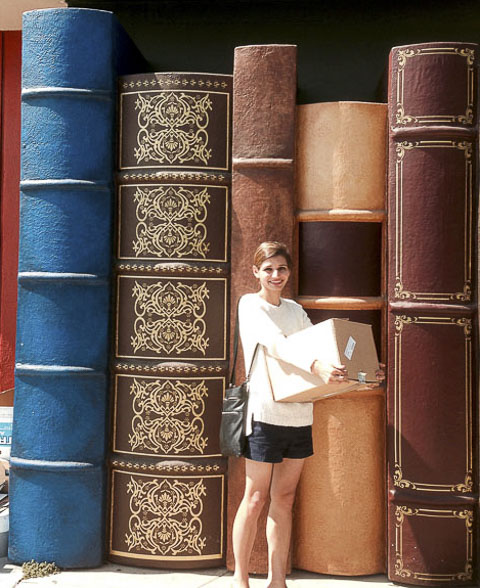

He stepped out of an imposing limestone hall in the streets between the New York Public Library and Rockefeller Center. He was in a corridor of private clubs, one of the last remnants of a handsome 20th-century midtown Manhattan aping the 19th, where a book party was ending for a woman he had not seen in ten years.

Surprised by the invitation, fingering the creamy paper of the envelope containing it as he entered the hall, still he reasoned, book parties are not exclusive social gatherings, though it was addressed in broad loops under the postal stamp in the blue ink of a fountain pen. Publishers want at all costs to fill a space where reviewers or agents for the movies may be lurking.

The invitation was in his breast pocket. Under the gold embossed print was a brief note in the author’s hand, “Dear Harry . . .” expressing the hope that he would attend. Gale’s book had not been published under her married name.

She was tall, imposing. Watching her strong back, broad hips, the thrust in her breasts, he had imagined what it might be like to encounter her in bed, to lie under a woman from the professional world of Manhattan. In her presence he felt short, diminutive, an amateur. At the party, circulating through the crowed, he recognized editors who determine the rise and fall of reputations. Something had urged him to come, but he saw that he was invisible to men and women who, when he was reviewing for newspapers with a national reach, gave him a respectful greeting. Gale, though, greeted him with a warm hello and he followed her around the room for ten or fifteen minutes, close to her elbow. After that the writer knew his presence would become obnoxious.

Gale’s husband was dedicated to social causes, also a legal scholar, writing essays difficult not to respect. Her husband had become engaged to Gale shortly after the writer had first met her. This had inhibited Harry’s thoughts about Gale under her clothes.

He had paused in the doorway leaving, feeling the chill air, before going out. He could turn back to where the book party was winding down. If he did tease her, would she slap him or be flattered? Seeing his age in a head of hair that had turned from pepper to white, the circles under his eyes, he recalled his first stare at her sharp, handsome features, the hectic flush in her cheeks. Was it twelve years before?

He set his shoe down on the cold sidewalk, swept of snow but treacherous in icy, early March; pausing to face a red brick façade across the street—the Harvard Club. The college was his alma mater.

At the party, a woman well tanned but breezy, firmly attached by a regime of exercise to the visual line between thirty-nine and forty, (but possibly seven years older), had noted his threadbare college tie emblazoned with Latin in its shields—Veritas. She asked, as if he were flaunting the association, “Do you belong to the Harvard Club?”

“I can’t afford it,” he answered, the edge of his mouth curling into his cheek, “Just the tie.”

Observing that she shifted her attention at this, turning away, he was free to listen as she began to talk with Gail, whom he had been standing beside for ten minutes or so. He knew no one well enough in the imposing space to go up and start chatting but he followed the movements of this confident, and he guessed successful professional, her trim, well-muscled backside. Was she an agent, an editor, a publicist? From the fragments of the conversation in the noisy room, an identity was hard to construct. “I’m Jewish but I drink,” he heard her say. As she wheeled on her high heels in svelte black slacks, he caught her goodbye.

“Your husband is so thin,” she barked.

“Yes,” Gail agreed.

With a pang, he saw the woman disappear in the crowd. His quip had cost him his existence in her eyes.

x

Facing the brick propriety of the Harvard Club he saw a familiar face, coming out, mocking, ironic, then looking through him, and walking away before he could identify her. Was it the editor of a review that had consistently rejected his stories? The Harvard Club—that was another world. What had happened to his early prospects? He felt as if back in the hall where the party was ending, as he had faded out of the woman’s eyes, a death sentence had been pronounced upon him.

Gale, how much he had been attracted to Gale, despite the sour shake of her head. The brusque, self-assured carriage that she brought from the snobbish world of her college campus; her slightly disheveled appearance at times, her disapproval of his manners, which reminded him of his mother; made him think there might be a link between them. She was statuesque but distant even as a woman in her early twenties. His former wife had once remarked on Galen as “belonging to the past century.”

“Exactly,” he had assented over their breakfast. Galen looked like one of the imposing carved figureheads that coasted the pages of Henry James and Edith Wharton; not their confused naive heroines, but the stiff, starched cousins, whose proper behavior and choices set the rules that heroines are born to break.

He had met Galen, or Gale (as her name had been fixed in his head), at a Jewish Studies Conference in Boston. It was a gathering he usually avoided; a place for specialists, and self-promoters, with panels and lectures on fine points of history, rabbinic learning, Hebrew or Yiddish linguistics. He was interested in many of the subjects but clichés of criticism were rife and with a tenured position at a college, he wasn’t hunting employment. Galen Edwards now Mussorgsky had attended a panel discussion, which he was induced by an old friend to join. Its subject was the possibility of establishing an American Jewish canon. The members of the panel were assembled almost at the last moment, and not listed correctly in the Association’s booklet of events.

He recognized among the participants as they gathered for a hasty session beforehand, a man whose articles celebrated the new lights of the Holocaust industry. He had awarded paeans to several “emerging” writers, whose work was hopelessly thin. With a sinking feeling, Harry sat down at the “planning” lunch to map out an outline for their discussion. The food at the famous Seafood restaurant proved insipid. A skinny sliver of cod loin, contrary to the waitress’s reassurance—“fresh”—had either been taken from a freezer in the frenzy of lunchtime lines or over baked. “Kafka’s cod,” he joked to the company about the mealy fish steak. They looked at him, puzzled, “Eaten by the worms of anxiety.”

The editor seated with them, paying for the lunch, was complacent. No one complained over the plates and as a guest Harry didn’t want to send it back. Earlier he had flirted with the waitress. Distracted by her and the fish, he had not followed the conversation about the seminar’s planning. Joining it now, he found he was not to present a paper he had prepared. His friend, a scholar whose work was respected in the academic bureaucracy, had scanned the paper, said it was fine but between forkfuls, the chair of the panel ruled “Not on topic. Speak spontaneously.”

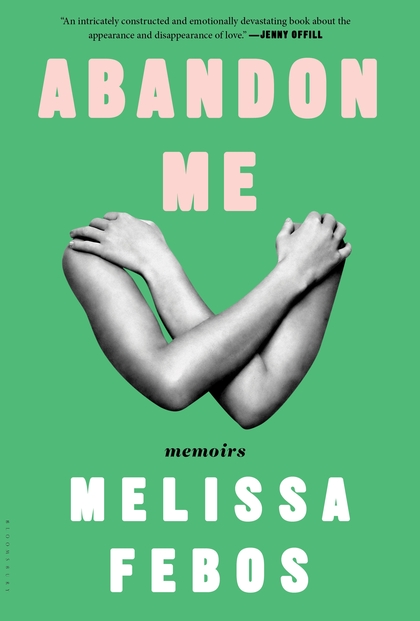

Earlier, he had been told to speak on the theme of a novel, which had won him his college appointment. It had challenged the clichés of the social critics who were predominant in the academic field. A Crazy Jew, Not Like You had a brief life getting mixed reviews in the national newspapers and literary journals but then faded from view.

He had written other novels, and books on the irrational, but none of them had won him much attention. Now working on a study of female devils in contemporary literature, he had hoped to simply read a few of this manuscript’s pages.

He suspected that it would never find a university press or trade publisher. He had conceived of a book into which he could disappear. Not just a commentary on older books but one in which its author lost himself like the Zohar’s author, seeking mystical union with the Unknown. He invented a world where narrators were taken up by a dangerous female presence fluttering over the universe. He linked Franz Kafka’s obsessions with women to Biblical heroines, spoke of the Jewish writers whose mothers were prostitutes, insane matriarchs, feminist “bitches” and succubae.

His friend had a sense of humor, and loved a good joke. But the panel’s chair, with a flat Mid-Western voice, interrupted his friend’s plea for the prepared pages. It was far a-field from a canon. “No paper,” Harry was warned, but the chair encouraged the writer to go over some of the ideas ad hoc. “Be spontaneous!” Spontaneity meant hours before the seminar making notes, unpalatable bits of fish grinding away in his stomach.

He did finally sway majority opinion at lunch on the fish, “Yes, yes,” they agreed, “awful”—cleaning their plates. Otherwise excluded, he went to a corridor of the hotel to find a chair and try to make an outline for an irrational “Jewish” canon.

At the seminar table he found himself assigned the last slot. The panelists droned on. Halfway through, two critics in the audience whose recent work he admired, filed out. “Come back!” but he tried to cry but stifled it. Depression fixed him to his folding chair. Only five or six people were in the seats by the end. As he spoke, his words sounded random and senseless in his own ears.

His eyes lighted on a young woman in the second row of seats. He clung to whatever her attention he could perceive. In the question period no one asked him anything but gathered up coats and scurried away. Dashing out of the room, to avoid apologizing to his friend, who lingered, he saw an impressive back and waist, a female form. It swayed in the lobby’s crowd as if detached from John Singer Sargent’s portraits of Boston debutantes. Strands of auburn hair fell over her shoulder. He caught up and touched an elbow.

“You were at my seminar,” he blurted.

Without waiting for an acknowledgment, he began a monologue mocking his own remarks at the seminar.

She did not disagree but interrupted him to single out one pronouncement of his with which she agreed. When asked for her reaction to the other speakers, instead of answering, she turned and left him standing under the ceiling of the hotel lobby.

Was she twenty-three, twenty-four? He had forgotten even to ask her name. Too far now for him to follow he watched her swim away into the crowd.

x

He was sitting at her elbow the next evening. “Do you know Gale?” his host, a professor at Harvard, asked, motioning Harry to a place beside her at a crowded supper table set for a dozen guests in a Cambridge, Massachusetts, restaurant.

“Are you Gale?” he asked.

“Gale, Galen, whatever you like best.”

She wasn’t, it seemed, Jewish, and that made her presence at the conference even more interesting.

“What do you do?” he asked.

She was a reporter for a major American newspaper, even though she was barely out of college.

x

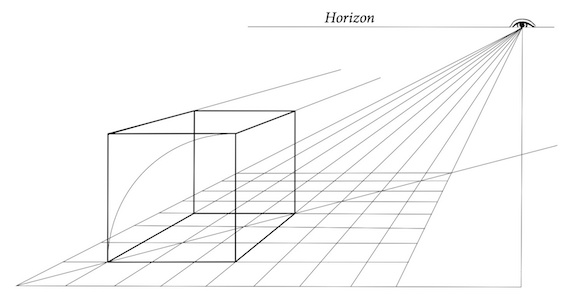

As he turned from the red brick front on the opposite side of the street, leaving the book party behind, the opaque mirror of limestone and glazed crimson brick in the Harvard Club’s front seemed to reflect his tie, frayed at the edges. Veritas? Gale, now, forever Galen, a friendly but distant professional, had been more than attentive to him at her party than he deserved. Given the high-powered circle around her, however she seemed to be sailing into their horizons.

Why was that painful? What did he want from her? He grasped at the thought of a much younger woman whom he had met a few months ago.

Over forty years separated them. The girl, only nineteen or twenty, had recently met with him in his position as editor of a small journal he continued to edit despite the waning of his career as a writer. She wished to discuss a piece she wanted to submit. It would be about myth and the sex life of Jewish women in religious worlds. In her eyes a streak of green ribbon darted out points of orange. She had laughed, puckering her lips as if teasing him, then told a story about an older man, her teacher—a rabbi in a religious high school, who molested her.

Reliving the moment it seemed, she spoke about the paralysis that gripped her as the rabbi’s hands began to wander. He reached under her blouse, into her pants. When the young woman finished, the silence in the air was charged. Harry had been unprepared for this when he asked her to meet him in a coffee shop, curious about what she might submit.

“No,” he admitted, taking one step after another over the icy sidewalk, afraid to slip and lose his balance. He had been more curious as to the person who would write the essay. Catching sight of her at the coffee shop in the blue denim jacket and dungarees, she told him she would be wearing, his heart stopped. She looked like a teenager. He was momentarily shaken into a state of vertigo, dizzy, afraid to meet her eyes, trying to take in the rest of her in the booth where she crouched as he slid in against the bolster on the opposite side.

How was it that she so quickly shared that story with him? A question kept running through his head when he got up to leave an hour later. Did she feel that he was attracted, even before she told him the anecdote whose purpose he started puzzling over later? Was it a warning shot across his advancing bow, or a provocation to come on faster? She touched him but it was not her body that was spinning him around but an idea.

x

Anger distorted her face as the girl had told about leaving the rabbi’s study, seeing the rebbitzin, his wife, washing dishes in the kitchen, pretending, the young woman said, bitterly, not to notice her agitation.

Who was she describing? Was there a rabbi?

He felt the magnetism this girl was exerting as she left, seeing himself against her in the flesh. Was that “bad” trying to imagine what she looked like without her clothes?

He wondered if she could imagine him looking at her.

How did she see him?

Was she setting up a trap? Did his caution mean he was he losing the force of a curiosity that had guided him to the worlds of platonic forms? Was he now just one of them”?

“I thought of him as my grandfather.” Her wriggle against the bolster of her booth’s seat back had stopped. She stiffened, displaced her smile. She stared as if daring him to stare back. Had the thought of physical penetration become worse than the taboo against commission? Was the act irrelevant if the thought had been committed? Was this the cursed life of angels when they rebelled in the story of the Flood?

x

He quickened his step outside the Harvard Club as the image of the girl who had come to see him slipped away.

What did he want? The stoplight at Forty Second Street, which separated the professor from the stream of traffic, brought him to a halt. The glaze of ice on the asphalt reflected nothing but he was conscious in this dark, slick surface of his body. He had lost some weight since his fifties. What did he look like? Teasing an undergraduate about his weight loss several years ago, he had asked, only half joking, “Aren’t I more attractive.”

“No,” she snapped. “You’re old. Aren’t you still married?”

Could the life he had constructed out of books answer what he wanted? And what was that intimacy which he brushed against in pages and sometimes in the faces of others?

“You are too naked,” his former wife had told him when he complained, a decade before, of his inability to speak with colleagues at the college. That nakedness, of course, had led him to behavior, which exhausted her patience. He saw himself in her clear blue eyes as a willful child, “You pay no attention to other people.”

Was that so? “You can be,” she admitted, “generous, attentive, but only because you feel that way, not because you see that whomever you are speaking to wishes for your attention.” Then his wife added, “Or that they want to articulate thoughts of their own.”

He stopped at the curb. He had paid attention to his teachers, and the older scholars he had befriended, their whispers out of the classroom, in the corners of comfortable, living rooms, He had collected stories of nakedness, forbidden unions—the annals of wife swapping sects of Turkish Jews, experiments with multiple unions through Polish towns, the far reaches of Hungary, Romania, villages beyond Prague—not merely for pleasure but in breaking a taboo, to go naked, to touch?

The rabbis were men of flesh. Yes, cautionary tales follow on the heels of breaking the law. Chaos sweeps up those who search for the Messianic when the universe will be remolded—that moment in Creation when matter separates, worlds divide, the rules of order still unset. Genesis’s first moment is cataclysm. Still, between the lines lurk a quixotic encouragement to overturn, to disorder—the Talmud’s adage, “Without evil there is no perfect service.”

What is the slight divide between a young woman now and my own adolescence; time is relative according to Einstein? And if I could go back in time, how far back? Would I travel to the abyss before the Beginning?

x

Do I in fact exist?

If I do, though disintegrating, the myth is to draw an angel into one’s arms, wrestle with it until ribs and tendons are exchanged; not boxed, wrapped in tinsel. Celan’s cry, “Über dich, Offene, trag ich dich mir zu.” Through you, Open ones, I bear you to me.”

One of the purveyors of the hip, the editor of a magazine New Judaism had crossed Harry’s path several years before when he was still being solicited to write about books. “Jazz it up,” she suggested after he sent his first draft in. He was reviewing an academic tome on the origins of mystical fantasies the mysteries of Lilith among medieval Jews.

“Jazz up a female Devil?” he asked. No one had previously required him to revise, not prominent newspapers or academic journals.

“You know—make her ‘hot’!”

He put down the phone, stunned but on the tip of his tongue, “Give me a lesson?” Like Gale the editor was tall, with an imposing body and a way of moving that attracted the eyes of every man in the room, though her voice had the grating accent of the Long Island Jewish mafia. He had snapped the remark back between his teeth. Would it amuse her—to be brazen? And why did he so frantically want to please while stung by her attitude?

x

“Why aren’t you funny, anymore?” a student had asked in his last class at the university. She was from New Jersey and had written a paper on the implications of hairstyle among suburban high school princesses. She had read his first book where good-natured laughter had made an impression that once had won him attention.

“What I found funny at your age, I can’t return to,” he answered. “What strikes me as comic now, after the death of my parents; after a career watching idiots advance, mediocrity triumph . . .” paused, but then said it, waiting to hear if she would react “a divorce.” After a moment of silence in which he could detect nothing from the expression on her face, he finished his sentence, “is different.”

She came to class in a skirt with a slit up its side, midway between her knee and her waist, a window of opportunity for someone as she tossed the ringlets of her long hair like a curtain, to the side. Does one have a right to desire her? And what did he desire?

x

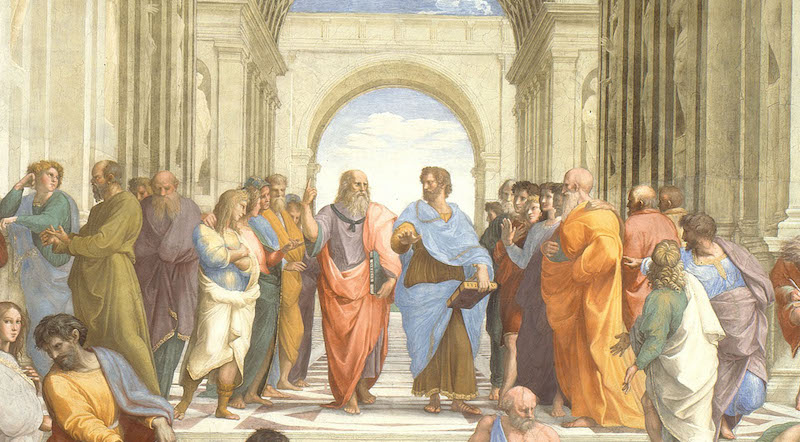

He turned to the story of Dante, who was not afraid to characterize himself as lecherous. The poet speaks of Beatrice’s eyes, whose light seems to touch him.

Still teetering at the curb, he wondered again about that woman, the editor, coming out of the Harvard Club, who seemed for a moment a double of the one who asked about his tie. Again the girl he had met a few weeks ago appeared to stare with an invitation into his eyes.

x

A former student of Harry’s, responding to his whining when she called to inquire about him, had offered an interview. She occasionally placed articles on a Web site about Jewish topics. “What are you seeking for in your books?” she read from a sheet when they met at his favorite coffee shop,.

He grasped for a formula that would be more than a vacuous generality. He named writers who had influenced his work. She broke into his catalogue, asking, “What did you find in those books?”

“I found voices that spoke to me.”

“What does that mean?”

“Take Dante trying to answer Beatrice’s accusation that he has been unfaithful.”

“You keep quoting books written from a male perspective. Your putative author of the Zohar, Moses de Leon, used women as the portal to sexual congress with Divinity as a mere vehicle of male passion.”

“You think that all things are sexual,” she added, smiling but with a faint pout of disapproval in her full mouth, cherry red, bright with newly applied lipstick.”

“Up to this point, sexual desire has been my most powerful experience of the ecstatic. To be swept up beyond your own self when voices speak through you is even more electric, overwhelming when you write.”

“It is the unhappy truth,” he continued, staying on topic—since she had come to demand an accounting for his “male perspective”— “that these are the books of men but they are also the imaginings of men and women. Dante had a wife, children, but he imagined a woman, Beatrice, who imagined him. A man becomes what a woman imagines him to be and so the woman becomes what the man imagines. Mystical union is impossible without that union in imagination through which they pass into each other.”

What does she make of that? he wondered as she smiled, picking up her notebook. They exchanged a polite, goodbye. She had been the brightest student in his class through several semesters. Who did she imagine he was?

x

He had tried to speak about these matters to the young woman wrestling with her rabbi against the booth, adolescence clinging to her. “What we imagine is real. Did Dante sleep with Beatrice? Almost all the scholars deny it and yet Beatrice tells Dante, ‘Never did nature or art present you / with a pleasure equal to the beautiful limbs in which I / was enclosed…’ How explicit can a courteous poet be? Dante is told he cannot have the body of Beatrice until The Last Judgment. He goes blind in Paradise when he is told this.” He wanted to ask, “Would you have been angry if the rabbi had only imagined making love to you? Was it the idea or the real touch of his fingers that appalled you?”

The professor had stared into her green eyes instead, and said, quietly, “Dante’s only hope for another consummation of adultery will be the day after the final sentencing.”

The young woman exchanged a smile as he whispered across the table. “Yet he is told he can ‘touch’ her through light, the light in her eyes.”

Only it was not only Beatrice Dante had desired, just as it was not Gale, or this girl, who he wanted to find on the sidewalk.

Only one woman had ever reconstituted herself through light in his imagination. Dante was afraid to mention her and like the poet, he shied away from that thought and once again summoned another image. It was Freud who understood Dante, poet and lover of the mother.

x

Why had he teased the girl about “touch”? Was he asking for trouble? After their meeting she sent in an essay was called, “Legend of the Patriarch, study in Lechery.” She had addressed it at the magazine to him. She was only a few years from the incidents she described. In the essay she had called into question the behavior of the Biblical Abraham through his final years. As an editor he didn’t see how he could publish it and yet he was loath to break off contact.

x

“Why did you write me?” he had asked the young woman, after they had introduced each other at the coffee shop.

“I read your article.”

Yes he remembered it. Frustrated by his inability to place “Age, Eros and the Dream of Time” anywhere else, he had broken a rule and published it in his own magazine.”

Now, on the cold corner, he wondered. Did you come to meet Abraham or your grandfather? And if it was the old patriarch, you imagined, what did you want?

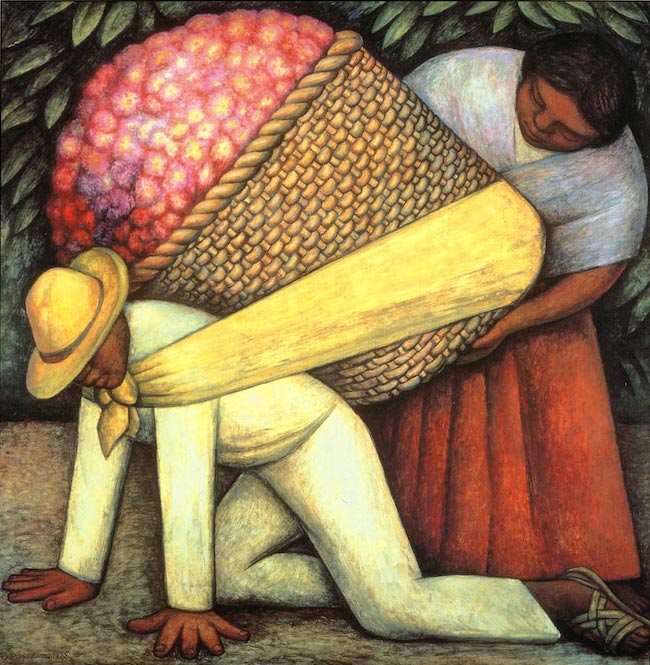

A part of love is loyalty, he thought. One turns to hide against the breasts or breast of the beloved, as a refuge from both the world, and the fear of death; to twist desire into a dream of flight to another world. To escape in metamorphosis into another body . . . ?

What did the rabbi want from the girl, and what did she want from him? Her story of seeking another life was complex. Was she fleeing a family, a dangerous patriarch, or looking for the disinterested love of another one?

x

“Tell me that I exist!” It was craven, but he wanted to cry, “Desire me!”

Was it possible to be desired through a whole life? Would children have changed him? Was that the true conduit for desire?

He recalled the lines of Yeats, who had evoked the other woman from whose shadows Beatrice had taken shape.

Being mocked by Guido, for his lecherous life

Derided and deriding, driven out

To climb the stair and eat that bitter bread

He found the unpersuadable justice, he found

The most exalted lady loved by man

And a moment later, about to cross the street, he wondered why, apart from the evening’s reception, the verse summoned Galen.

She had lost that fragile edge he and his wife had noted— adolescence blossoming into womanhood with hardly an awkward moment. Despite the whirl of recognition, publicity, in the hall behind him, he suspected it wasn’t a career, but babies to whom she would give her breasts, thighs, and the last glimmer of power as he had imagined her, “that fierce virgin,” fading.

It was . . . He stopped again, noting the danger—traffic was heavy.

x

Gale was still handsome, but at the reception she had whispered, happily that she was expecting. She was passing, content, into child bearing and where she might forget a career. It was only in that friend’s cruel eye on his tie that he had felt a searching intensity, a desire that touched him with light from a world of fantasies.

x

The father in Kafka’s story “The Judgment” sees his son’s sexual interest in anyone else as a betrayal of the mother. “Because she lifted up her skirts,” the old man mocks, referring to his son’s girlfriend; disgusted by the sight of a woman’s vulva. Kafka and his friends thought this very funny but the writer set the accusation down and was never able to marry. Harry paused about to take the last steps into the street, as if his mother could hear him, “Who am I?

“Is life an idea, a leap forward to find that flash of light, sun burst that it escaped from but now wishes to fix in the disintegrating matter of the universe? Can I escape into a book and lie there waiting for the embrace of another to take flesh again?”

Does what we do write in the universe? Do we write only in our bodies and those of others? Spinoza thought that in the ocean of being our experience inscribes itself on matter? Does it matter? The pun asks—are matter’s components indestructible, do they face extinction in a black hole? Before the Big Bang and after the last whimper, does anything matter?

An old man or woman’s fantasies—leagues away from the girl, Gale caught up in the publicity of a first book, or children. Who is real at this moment, Galen, the girl, my wife?

I am stepping into Kafka’s suicidal point, he thought, recalling the end of The Judgment. The son grasps the railing of a bridge, its traffic “just starting up,” cheerfully accepting a father’s verdict: “I sentence you to death!” Kafka read this to friends who burst into roars of amusement, rolled on the floor. “‘Dear parents, I have always loved you all the same,’ and let himself drop.” At that moment, Harry heard Manhattan’s unending stream of traffic blare. The light changed and he and his thoughts dropped into it.

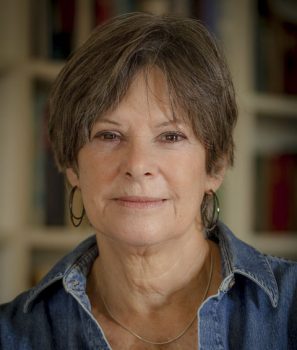

—Mark Jay Mirsky

x

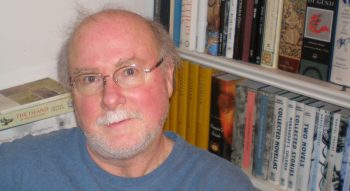

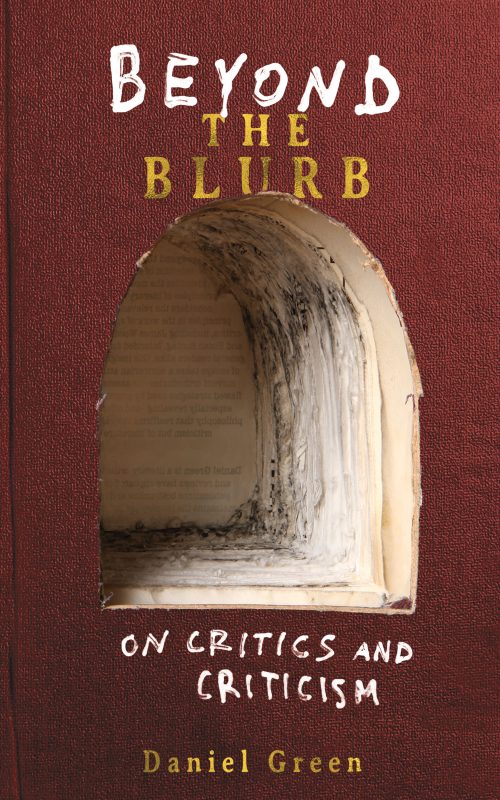

Mark Jay Mirsky was born in Boston in 1939. He attended the Boston Public Latin School and Harvard College and earned an M.A. in Creative Writing at Stanford University. He has published fourteen books, six of them novels. The first, Thou Worm Jacob, was a bestseller in Boston; his third, Blue Hill Avenue, was listed by The Boston Globe thirty-seven years after its publication in 2009 as one of the 100 essential books about New England. Among his academic books are My Search for the Messiah, The Absent Shakespeare, Dante, Eros and Kabbalah, and The Drama in Shakespeare’s Sonnets: “A Satire to Decay.” He edited the English language edition of the diaries of Robert Musil, and co-edited Rabbinic Fantasies and The Jews of Pinsk Volumes 1 & 2, as well as various shorter pamphlets, among them one of the poet Robert Creeley. His play Mother Hubbard’s Cupboard was performed at the NYC Fringe Festival in 2007. His latest novel, Puddingstone, can be found on Amazon Books, both in digital and print-on-demand editions.

He founded the journal Fiction in 1972 with Donald Barthelme, Max and Marianne Frisch, and Jane Delynn, and has served since then as its editor-in-chief. Fiction was the first American journal to publish excerpts in English from the diaries of Robert Musil. Subsequently it has published translations of plays and other materials of Musil.

Mark Jay Mirsky is a Professor of English at The City College of New York.

x

xx

x