The election of President Obama and the economic policies of his administration play like “trickle-down justice.” But, whether he has a choice or not, he is just a puppet to the corporate state, just as any other president would be in today’s polarized, cynical, economically fixed electoral system. —Tom Faure

Wages of Rebellion: The Moral Imperative of Revolt

Chris Hedges

Nation Books, May 2o15

304 pages, $26.99

.

Drones, the Patriot Act, stagnant real wages, failed public schools, a compliant press, the state’s shutdown of the Occupy movement, Citizens United, Stand Your Ground laws, stop and frisk, Ferguson, fracking, wiretapping, and the continuous mistreatment, often violent, of minorities, women, and particularly trans people. That’s just the tip of the U.S. iceberg. Then you’ve got the rest of the Earth: poverty, hunger, slavery, and injustice—compounded by the effects of global warming.

We’ve heard it all before, and the liberal mainstream has given up due to cynicism and lack of imagination. The lack of a simple solution dispirits idealists. The politics may be boring, but the situation is dire.

Chris Hedges’ Wages of Rebellion, published in May by Nation Books, reminds us of just how dire, chronicling a litany of anti-constitutional practices undertaken by the U.S. government, often in service of what Sheldon Wolin called “inverted totalitarianism,” a state run by corporate interest. Hedges does not offer any policy-based panacea, the absence of which will disappoint those looking for quick fixes. Indeed, this important book is more a mix of genres. Over his years of international reporting, Hedges has spoken to rebels like Axel von dem Bussche, Julian Assange, Mumia Abu-Jamal, guerrilla fighters, hackers, defense lawyers, Occupy members, and others who toil in the name of social justice. By way of the theories of Gramsci, Havel, Mandela, Baldwin, Paine, and Kant, the book is a series of portraits of these dissidents and rebels, exploring whether a true revolution is in the offing and who the main agents of change would be.

Hedges’ central thesis is that revolution cannot be purely intellectual. He examines the character trait Reinhold Niebuhr called “sublime madness.” Hedges quotes Niebuhr’s declaration that “nothing but madness will do battle with malignant power and ‘spiritual wickedness in high places.’” Liberalism is too rational, fearing the emotional component necessary, Hedges and others argue, to revolution. The possessor of sublime madness has foregone the mores of the state in favor of universal moral laws—embracing Kantian dignity and duty despite public ridicule and, frequently, violent retribution.

If there’s one thing you can count on in mainstream political discourse today, it’s that it will be dismissive of unquantifiable notions such as truth, love, passion, and fairness. Probably, this is because political discourse is so widely corrupted by neo-liberal ideology, which looks down on these notions with impatience or, sometimes, an embarrassment born out of, I think, fear and insecurity. Liberalism too often allies itself with one of humanity’s more exploitable capacities: rationality.

These abstract notions and their emotional cousins that receive this lazy derision are precisely what those yearning for revolution must not overlook, according to Hedges. An emotional force is the true catalyst—a force born out of misery but also frustrated expectations. Herein lies a major obstacle to any potential New American Revolutions. The masses are placated because their expectations are not frustrated to a large enough extent. They are sipping caloric Starbucks Frappucinos, commoditizing their digital avatars via the strict norms and algorithms of Facebook, freely handing over to corporate interests their valuable political and commercial data. The poor are angry, yes. But the middle class is sedate.

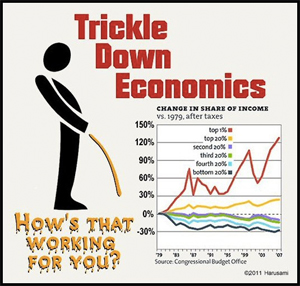

At Columbia University—a bastion of fascist anarchism, if you believe Bill O’Reilly—a standard introductory macroeconomics course includes on its syllabus, as would be expected, the vastly influential thinker John Maynard Keynes. Bravo, Columbia, you lefties! But Keynes makes up perhaps 2 percent of the syllabus, and he is the only economist featured who offers any critique of the supply-side economics pipedream known as the trickle-down effect. As an 18-year-old student, I was shocked and confused by the lack of rigorous critique of neoliberalism initially offered to undergraduates.

As Hedges notes, faith in the trickle-down effect plays an important role in the global takeover of corporate interests in politics, policy, and culture. The idea that the rise of the elite will benefit the weak is very compelling, for multiple reasons. There’s only one problem. The people “benefiting” from the elite’s exploitation of labor and resources are not the weak who can’t help themselves. They are the middle class—those hanging on by a thread as real wages decline and citizen rights become hollowed out. The weak? They’ve already been eliminated.

A similar dynamic is in play with regard to race. The election of President Obama and the economic policies of his administration play like “trickle-down justice.” But, whether he has a choice or not, he is just a puppet to the corporate state, just as any other president would be in today’s polarized, cynical, economically fixed electoral system.

The result is the totalitarianism of the invisible hand. Real wages have not increased in decades, millions of people, especially minorities and especially African Americans, are incarcerated thanks to Bill Clinton’s easy-plea-one-two-three, and even if Black Lives Matter takes off, the Keystone XL Pipeline will probably contaminate millions of people’s water on its way to contributing catastrophic greenhouse gases to the environment.

Hedges posits that revolutions happen, not when the people are subdued by total abjection, but rather when they have had a glimmer of hope. Raised expectations follow technical innovations and a rise in the standard of living—this is when the failings of the state, and its all-too-frequent efforts to smother dissent, fuel the fire of rebellion. Much of the battle is invisible, residing in the language and metaphors of the people. Organizing and community-building facilitate the evolution and sharpening of a language necessary to articulate the emotion awakening in the people.

Another key factor, Hedges writes, is the use of nonviolent civil disobedience. Descending into violence or property damage legitimizes the state’s violent response in the eyes of the masses, whose emotional reaction is so key to the success of the revolution.

The growth of social media might offer a beacon of hope. However, Hedges writes, even in this relatively promising domain, dissident leaders fear the state’s ability to infiltrate and control virtual space:

It is only through encryption that we can protect ourselves, Assange and his coauthors argue, and it is only by breaking through the digital walls of secrecy erected by the power elite that we can expose power. What they fear, however, is the possibility that the corporate state will eventually effectively harness the power of the internet to shut down dissent.

Hedges’ book is a multidimensional, somewhat scattered, consistently incisive exploration of the psychological and linguistic margins upon which any revolutionary fervor might explode in the coming decades. Its critics have rolled out the hackneyed rebuttal: “well, if not global capitalism, then what?” Their claim is that Hedges does not offer any new ideas, dismissing as recycled his calls for civil disobedience and labor organizing. But, just because he doesn’t offer a structural alternative to neo-liberal ideology, that does not make the status quo acceptable.

Besides, the main weakness of Wages for this reader is that it’s simply not terrifically written. Too many instances of awkward syntax break rhetorical flow. Hedges is very thorough—the bibliography offers a comprehensive education on the anarchist critique of both capitalism and communism, as well as on the litany of injustices perpetrated by the U.S. government against its people and those abroad—but he also has a tendency to repeat himself, which can be challenging to a reader seeking the next step of the argument. At other times, Hedges does the opposite, veering into hyperbolic leaps of logic without sourcing data—odd, given his assiduous sourcing otherwise—or leading the reader step by step through the argument.

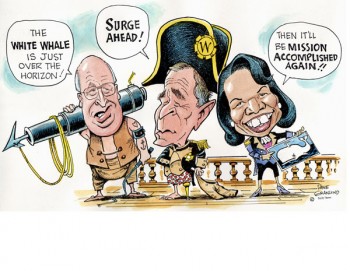

But these are quibbles, because the book is a political manifesto of sorts, not, say, a piece of literary fiction—yet they do matter, because the book could have been more ambitious. It flirts with cultural criticism at times, elevating the discourse on fanatical capitalism to the metaphorical and literary levels—notably, drawing analogies to Moby Dick. But then Hedges either pulls back intentionally or loses interest in the metaphorical thread, I can’t tell which.

Herman Melville’s odd masterpiece is an ode to the ocean and, though his narrator Ishmael warns against viewing the tale as an allegory, a frightening portrait of capitalism as seen through the whaling industry. Captain Ahab, a fanatical sea wolf, is hell-bent on killing the eponymous great “white whale” that took his leg. Ahab is prepared to forego the massive profits of the whaling expedition as he focuses his energy and his men on finding and destroying this one whale. His language contains sublime madness, which is unfortunate for the crew, all of whom will drown because of Ahab’s charismatic quest. Starbuck, the first mate, is one of the few who expresses doubts about Ahab’s plans for the Pequod.

The crucial moment comes in Chapter 36 when Ahab enthralls his poor, exploited crew with glorious visions of killing Moby Dick. Ahab notices Starbuck’s uncomfortable look. He invites Starbuck to respond, in full view of the crew. The first mate initially expresses his worry over consigning the entire enterprise to his “commander’s vengeance.” Ahab rebukes this swiftly, using revolutionary language (my emphasis added):

How can the prisoner reach outside except by thrusting through the wall? To me, the white whale is that wall, shoved near to me. Sometimes I think there’s naught beyond. But ’tis enough. He tasks me; he heaps me; I see in him outrageous strength, with an inscrutable malice sinewing it. That inscrutable thing is chiefly what I hate; and be the white whale agent, or be the white whale principal, I will wreak that hate upon him. Talk not to me of blasphemy, man; I’d strike the sun if it insulted me. For could the sun do that, then could I do the other; since there is ever a sort of fair play herein, jealousy presiding over all creations. But not my master, man, is even that fair play. Who’s over me? Truth hath no confines.

Starbuck folds. He lacks the sublime madness (which, interestingly, Ahab does possess, as Hedges acknowledges) or language of rebellion to mutiny against his commander. He bemoans that Ahab has “blasted all my reason out of me!” Hedges writes: “Starbuck especially elucidates this peculiar division between physical and moral courage. […] Moral cowardice like Starbuck’s turns us into hostages. Mutiny is the only salvation for the Pequod’s crew. And mutiny is our only salvation.” Hedges makes a compelling argument that today we have too many Starbucks.

Much of Wages focuses on cataloguing the injustices meted out by the state, only reserving a portion of its energy for portraits of rebels and an exploration of this sublime madness. Hedges does not explore with sufficient force how the quality might develop and how those possessing it will harness their passions and wake the masses out of their slumbers. What does emerge, though, is a compelling spotlight on those who are in the trenches today.

“You can’t fight power if you don’t understand it,” says Abu-Jamal from prison. Better understanding can only aid the cause—but until the corporate state trips up in its successful smothering of the will to understand, there’s little chance sublime madness will penetrate the middle class; without this, any real wages of rebellion will continue to stagnate against the inflation buoyed by mainstream narratives of capitalist ideology.

—Tom Faure

.

Tom Faure received his MFA in Fiction from Vermont College of Fine Arts. His work has appeared in Waxwing Literary Journal, Zocalo Public Square, and Splash of Red. He lives in New York, teaching English and Philosophy at the French-American School of New York.

Contact: tomfaure@old.numerocinqmagazine.com

.

.

A terrific review, better written than the provocative book being analyzed. As for the concluding paragraph citing Abu-Jamal: I don’t have sufficient “sublime madness” to join Tom and others who refuse to believe that Abu-Jamal killed that police officer. But that aside, both Hedges’ book and this review should be read,

Yes, this review is a stellar consideration of the work at hand. But its true strength is in Faure’s dexterous handling of the larger political and cultural underpinnings. He is, on a whetstone of logic and emotion, “sharpening…a language necessary to articulate the emotion awakening in the people.”

Hedges isn’t really taught in academia, as his audience is the educated public en masse. I interviewed him earlier this summer about poverty and crime; he confessed he was no scholar of Marx, but appreciated the conflict inherent to his worldview, and his insistence that high capital has a way of commanding people to do what it wants.

Hedges is a force for good, I think. Even the graphic novel he authored with another journalist wasn’t bad. Empire of Illusion was better than other of his work I’ve read, but unfortunately, he does focus too much on the worries of the well-off. Most people couldn’t give two shits about what goes on in the university classrooms. They’ve got bigger fish to fry.

Biggest thing he’s done, I’d reason, is to liberalize religion for an audience that was already predominantly secular. As a left theologian, he’s catalyzed, or helped to catalyze, a movement forward from the conservative nightmare that is the American divinity, and he’s done so in a fabulously public way. Also consistently writes about race in a way that doesn’t seem rent-seeking, as with Tim Wise, who is no more than a purveyor of racial sensitivity. No scholar is he.

And honestly I don’t think “middle class” means anything at all anymore in America. We have universal education, and it’s pretty dismal across the board. Most people don’t own very much, most people certainly don’t own much as to the means of production or even stock shares, our healthcare system is happy to give sub-standard treatment to insured and uninsured alike. Culture is largely homogenous compared to that of other high-population states.

If there is truly a revolution–an event or series of them about which I am pessimistic, since it seems as realistic as the right-wing variant of Red Dawn–it will come from the poor, or from the posturing middle that recognizes how poor it is. I see very little difference between people who are one paycheck away from homelessness, and the homeless themselves. That imaginary buffer was created through habits of consumption which ended up making the middle worth less in real terms than the toiling poor, who at least try to avoid debt at all costs.

All else is the rage of people who are getting beat by their own game, how the poor and non-white always have been. This is why you hear talk of capitalist acceleration–the sooner you accelerate mass exploitation, the sooner fire breaks out.

Though I am happy radicalism is experiencing a come-back in our era. Very healthy for a democratic milieu. Still count meeting Chomsky and Davis as one of the best events in my life, and the general zeitgeist of educated revolution-dreaming might do very good things for our country even if they don’t produce a practical revolution, which, of course, the state will not and never will allow.

A good review. I write for Numero Cinq sometimes and Hedges caught my eye. I’ll have to get his latest book. And just so you know the man is amenable to personal email, as all good public intellectuals are.

Thanks Pat, Geeda, Jeremy. I was off the grid for a bit. Appreciate the comments. As Marx realized (and Henry Ford really subverted this) the only time to really expect revolution is when the middle (class) erodes and we stretch the class polarization as far and taut as can be.