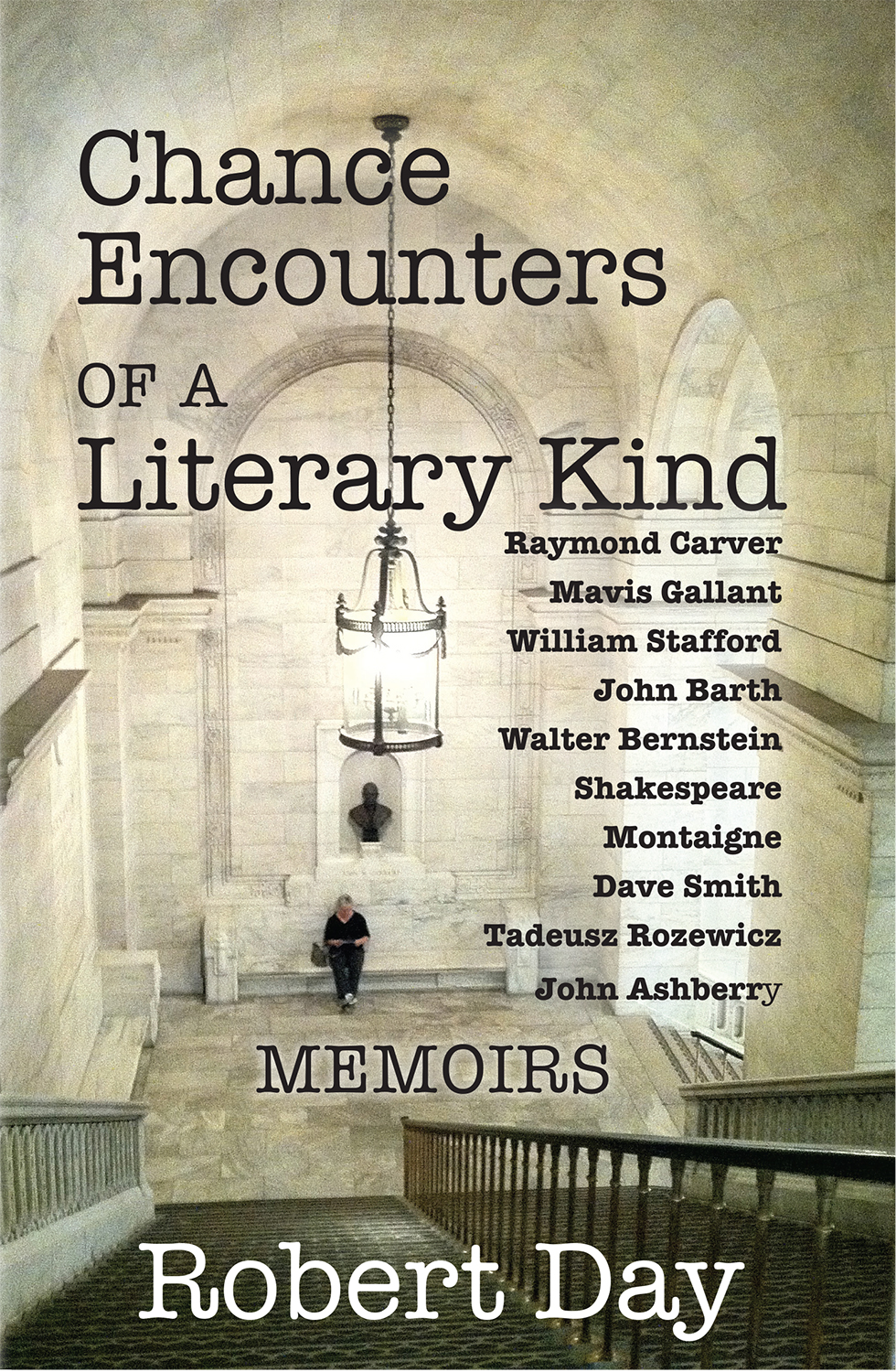

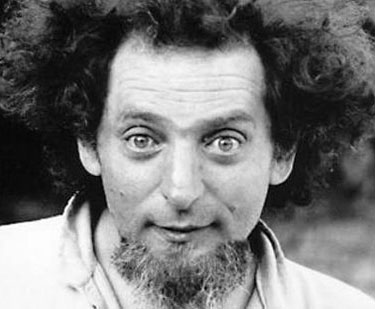

Diane Lefer by Robin Gibson

Diane Lefer by Robin Gibson

.

One morning in October I waited at the gate of the Air Ground Combat Center Marine training base in the Mojave Desert, Twentynine Palms, CA. I’d been invited with a community group about to take a public tour of what is essentially a grad school for combat. Marines from around the country–units 1,000 members strong–who’ve already completed basic training and are almost ready to deploy come here for 35 days of intensive work, including live-fire training and urban warfare practice in “Little Iraqi villages.”

Mockup of an Iraqi village for training.

Mockup of an Iraqi village for training.

“I don’t care if you learn anything today,” said the retired Marine who would lead our tour. “I’m here to keep you entertained. At the end of the day, if you don’t have fun, it’s my fault.”

But first, our drivers licenses were collected. Quick identity checks “just to make sure you’re not a terrorist.”

We waited. A woman near the front of the parking lot stared, scrutinizing me.

For a few years, my emails carried an automatic tag at the end: I am a terrorist. By paying US taxes, I provide financial support to State-sponsored terrorism and torture. I don’t remember when I deleted the statement, but it occurred to me my past might have caught up with me.

The woman beckoned to me. “Are you a writer?”

Well, yeah, but I wasn’t there on assignment. A nonprofit I’m associated with was interested in doing outreach to vets and active service members in the area.

“You’re media.” Her definition turned out to be rather encompassing: Anyone with a blog. “You’re not allowed on this tour.”

I hadn’t planned to write about the day but I let her know I would damn sure write about being left outside the gate.

During the 4-hour drive home, I realized what I really needed to write about was the loaded word fun.

Warning sign at 29 Palms.

Warning sign at 29 Palms.

****

Does any culture have as much of it as we do? When I try to find “fun” in other languages, I can’t seem to come up with a true equivalent. I find terms I would translate as amusement, diversion, joke, prank, leisure. None of which to me quite conveys the same meaning as fun.

****

A few days later I’m at one of the monthly workshops on nonviolent action led by civil rights hero Rev. James M. Lawson, Jr. We’re considering violence in Iraq, Afghanistan, Syria, Palestine, and why governments see no alternative to war. Why is military force the default position? Why isn’t the peace movement effective?

I brought up the Marine base. What did the nonviolent movement for peace and social justice have to equal the promise of fun? To get people’s attention these days, so we have to compete with pulse racing, adrenaline-pumping excitement? The Civil Rights Movement was one of the most successful examples of nonviolence, and I dared to say it drew people to it through the promise of risk and adventure.

I knew the words were wrong, but I was trying to figure something out. What elements made it possible for the Movement to mobilize a whole nation, cutting across lines of race and class and gender?

Two of the Black participants in the group caught me at the break. Maybe it was an adventure for white kids who went to Mississippi for a month or two, they said, but for the Black people who actually lived there, there was no adventure. There was the same violence and oppression they had always lived under.

Of course they were right. And forgive me, insensitive, offensive, I kept talking. Instead of thinking aloud I should have just kept my mouth shut. Instead, I knew they were right so I stopped listening and kept trying to figure out what I meant, trying to account for the difference between suffering the constant threat of violence versus choosing to put your life on the line. There was something galvanizing in the Civil Rights Movement. Something made people embrace the cause and the risk. Wasn’t there excitement at the idea that through people claiming their own agency things might actually change?

****

Rev. Lawson doesn’t often focus on what’s happening overseas. He’s said we must confront the culture of violence here, not over there. The road to peace is justice. Dismantling racism and poverty, stabilizing families by good employment, by health care in the United States–that’s what is critical for the security and wellbeing of the nation. “Only by engaging in domestic issues and molding a domestic coalition for justice can we confront militarization of our land.”

****

“Our job is to engage and go through the enemy. Our job is not to take and hold territory,” said Mike, the ex-Marine tour guide.

I was back at the gate. See, after I gave up and drove home, Barbara Harris, who leads tours in the Joshua Tree area, wrote a complaint about how I’d been treated. The response came from public affairs officer Captain Justin Smith. I had his personal guarantee that I could tour. And he made no objection when I said I would, after all, write about it.

Mike said, “We kill everything that we see and let them (the Army) hold it.”

Mike wears a cap from Disneyland.

****

1200 square miles of desert. Even for someone like me who loves the desert, this barren landscape is hard to love. Marines here are housed (when not out in the field) in small K-Spans, structures that used to be called Quonset huts. Concrete floors, no cell phone reception, no A/C, no heat for the freezing desert nights.

60# of gear.

But foodie-inspired MRE’s? I spot a pouch labeled “Chicken and Pasta in Pesto Sauce”–a far cry from what my father said the mess hall served during WWII: DVOT (Dog Vomit on Toast) and SOS (which I later learned–because he always refused to tell us–stood for Shit on a Shingle). Then I try to picture that grainy green sauce and imagine today’s Marines, too, have come up with a suitable acronym.

****

Mike divides us into three groups to try out the Combat Convoy Simulator. Each group is in a separate room with a fullsize Humvee to drive, with gunners armed with M16s to provide security front, rear, right and left. We are to start off from Camp Dunbar and travel Highway 1 to the village of Asmar. Our mission is to get there and return without getting killed. “Don’t shoot people that are not shooting at you,” Mike warns. “If you shoot the noncombatants they get cranky and everyone will be your enemy.” The whole room becomes a 360-degree video game projected on the walls. We can see the other vehicles. We can see “Iraq” all around us.

Video view of Iraq highway created for training.

Video view of Iraq highway created for training.

Captain Smith hands me an M16 and I hold onto it awkwardly as I try to put my camera and notebook away. “Here.” He takes it from me and replaces it with an M4– “the girl version.”

The rifles in the simulator fire compressed gas, making a sound like live gunfire. The recoil is just like real.

We’re the first vehicle in a convoy of three. I’m guarding the left side of the Humvee, watching for bad guys as video images move across the wall, and while I know I’m not as strong and fit as a young Marine, I’m still shocked at how much the weapon weighs, how my heartbeat speeds up and adrenaline surges from the mere stress of holding it in ready position.

We drive past market stalls where locals eye us, past fields where men move with their flocks, past kids on bicycles. Mike tells us to watch out for anything that might be a roadside bomb. Watch for people running towards us. They’re the insurgents. You don’t shoot at people running away.

Inside the Combat Convoy Simulator.

Inside the Combat Convoy Simulator.

My group wiped out some insurgents and didn’t kill any civilians. One of the other groups was too trigger-happy. In the end, we’re blown up by a roadside bomb.

Even after the exercise ends and I relinquish the M4, my hands are still shaking.

****

Humvees are obsolete. Too vulnerable to IED’s. Defense contractors came up with the Mine Resistant Ambush Protected Vehicle–the MRAP. The thing is, to make the vehicle adequately protected, it’s so top heavy that it will roll over even on an incline as gentle as 15-17 degrees. If it does, 8-10 Marines and sailors, with all their bulky gear, have to be able to open the 18″ x 18″ escape hatch and get themselves out, evaluate anyone who is wounded, and establish a 360-degree security perimeter. In 90 seconds.

Eight of us climbed in, fastened (with difficulty) our 5-point harnesses, held tight to our possessions as the MRAP tilted over on its side, and then the other side, back and forth and almost upside down as we screamed with shock and dizziness and delight.

We weren’t asked to escape. We climbed out, disoriented and shaken, asking How on earth do they do it?

Equipment waiting for us at the MRAP.

Equipment waiting for us at the MRAP.

Captain Smith smiled and told of other impossible feats the Marines are trained to accomplish. As we walked on, I thought, but of course! It’s not a race. It’s not every man for himself. It’s about preplanning and teamwork. At least I think it must be. That’s what the training was for, so the men already know who opens the hatch, who climbs out (or gets boosted out) first, and how or if they help others, and where they stand in the perimeter and how the plan adjusts if someone is wounded and can’t perform his role. It would have been interesting to hear how men learn to cooperate. Instead, we had a Disneyland ride.

****

90 seconds to egress an MRAP. 60# of gear.

A young man my niece dated for a while joins the Marines. He wants to serve and I insist he should have joined the Air Force where you get treated better. I don’t understand that being treated better isn’t what some young people look for.

How on earth do they do it?

First the sheer physical and mental endurance, the brutality of basic training. Then Twentynine Palms. I come to appreciate the thrill and the pride that must accompany the challenge of accomplishing acts that seem impossible until you actually accomplish them. Even before they’ve faced threats to life and limb, they’ve had to prove themselves in ways I can hardly fathom.

What do I do–what have I ever done?–that demanded so much of me, that was so worthy of stunned respect?

For an effective nonviolent movement, don’t we need to be every bit as committed? To accept that waging peace is every bit as difficult as waging war and demands just as much sacrifice? In the Civil Rights Movement, people knew they might be injured or killed. Those who were Black were in constant danger of being injured or killed with or without a Movement.

But there’s something Sisyphean about the young Marines.

What is the point of pushing men and women to the breaking point, training them to perform superhuman feats if all we’re going to do is send them off to kill and risk life and limb in unjust, ill-conceived wars? Wars we cannot win.

****

World War I broke out in Europe in 1914 and a century later historians still can’t make sense of it. Millions of lives lost, carnage, destruction, suffering and no one can give a good reason why. The Great War was so horrific, humankind was supposed to have learned its lesson. Instead it turned out to be merely the prelude to more death, more suffering, more war.

To mark the centennial, the Goethe Institut-Los Angeles offered Make Films, Not War, a series of screenings, lectures, and workshops. When Ajay Singh Chaudhary, the founding Director of the Brooklyn Institute for Social Research, and his colleague Michael Robert Stevenson presented their work on video games, I was there.

Please credit Chaudhary, Stevenson, and the Institut when I refer to gaming as prior to their workshop, I had never played a video game. I had never watched anyone play, none of which had ever stopped me from talking about how terrible the games are.

My only experience was this: Before Antioch University-LA moved to its campus in Culver City, when I taught there, classes were held in a modest building in Marina del Rey. The floor above us was occupied by a defense contractor developing video war games. A student might be reading her work aloud or we might be translating Chinese poetry or doing a rhetorical analysis of the Declaration of Independence, our words punctuated with explosions coming through the ceiling and walls.

More than 2,000 video war games are on the market. Some of the most violent games young people play for entertainment–for fun–were developed with funding from the Department of Defense.

****

Do violent video games lead to violence? Chaudhary says the studies are contradictory and inconclusive. Wouldn’t they have to be? Every individual reacts in his or her own way.

Years ago I’m sitting in the auditorium at the New York Public Library for a free screening of Buñuel’s film, Un chien andalou. Insects emerge crawling from the hole in a hand and a man in the audience rises to his feet. “That’s what happens!” he cries. “I told them! It’s true!”

This year, while writing this essay, I rush to see American Sniper, sure that it will bolster my argument about fun and entertainment. I don’t even mention it in the early drafts. No point in talking about the politics of the film, I thought, when in spite of the violence, it’s really pretty dull. Such an mediocre movie won’t get much attention, I thought. Shows you how much I know.

While in the meantime, ISIS posts online graphic video of beheadings. Most people are appalled. Some are thrilled. Some conclude ISIS should be destroyed. Others, drawn by the display of raw power, want to join.

Do we have to think about how every conceivable person will react to every conceivable content?

Specially designed video games are being used experimentally, I’ve read, to treat combat veterans suffering from PTSD. Virtual reality puts them back into the extreme situations that caused the trauma. The hope is to desensitize, to let the veteran relive the experience but in safety and with the ability to stay in control. Virtual violence that heals.

We watch a little boy as he plays Call to Duty, his hands flying, his body moving rhythmically with the first-person shooter action. The scenery changes at high speed and the kid is shooting and killing. A dog appears on the screen and for a moment, the little boy stops and just looks. “Dad,” he says, “can I have a dog?”

The game, the fantasy of the game, doesn’t change who you are.

Or does it? You get to choose your weapons. There’s a whole array with all their technical specs. The game can develop some serious expertise about military arms and it seems to me that expertise is something a person wants to use, and using it to play a game may not be enough. When you become confident and expert, won’t you identify with the endeavor? Are these video games excellent recruitment tools for militarization and war?

****

There’s a powerful resistance to killing deep in our moral structure, maybe even in our genes. Up until the time of the US war in Vietnam, most soldiers refrained from firing their weapons or intentionally fired above the heads of the enemies. So, as Lt. Col. Dave Grossman explains in On Killing: The Psychological Cost of Learning to Kill in War and Society, by the time we charged into Vietnam, the military had developed psychological methods to improve the kill ratio by breaking down this natural resistance. But what happens afterwards? For some soldiers returning to civilian life, violence may no longer be taboo. For others, this sense of moral injury, of having become something he or she cannot even recognize as the self, remains an open wound. We can break down a person’s character. How do we build it back up?

****

Can peace be fun? Well, the Sixties. Sex. Drugs. Rock n Roll. Make Love Not War. But did that bring peace?

How do we compete with kicking down doors and blowing things up?

Video war games have extraordinary production values. They put you right into the action. They are expensively produced, sometimes with funding coming right from the Department of Defense. Many of the pro-peace games I saw use comparatively low-budget graphics. Little more than cartoons. And instead of adrenaline-pumping excitement, they offer earnestness.

We Come in Peace, more sophisticated, uses 3D satellite imagery but apparently only a trailer is now available. It’s designed so that when you play you see our earth. The goal is to move in on location after location and eliminate the stockpile of weapons. I see how a player can get involved in the task, but you can’t compare it to the excitement of a first or third-person shooter game. Instead it resembles more closely the experience of a drone pilot. Except the pilot is eliminating human beings.

The drone pilot may learn days later that he or she hit a wedding party or a funeral and will have to live with that knowledge. But it’s not quite the same as the player of Spec Ops: The Line who has a mission to accomplish in the Middle East. As the game progresses, you find yourself on a killing spree, women, children. By the end of the game, you realize you are not a military hero but a psycho killer.

Will some players smile with satisfaction? Embrace the identity of a psychopath?

****

I strike up a conversation at the workshop. The guy is Israeli and he tells me about Peacemaker, a game which challenges you to bring about a just peace between Israelis and Palestinians and win the Nobel Prize. You can play as the Palestinian president or the Israeli prime minister. You are called upon to make decisions in response to events and you then see the consequences of your decisions.

When he played the Israeli side, he told me, it was relatively easy to choose actions that led to peace. But he was entirely unable to imagine his way into the role of the Palestinian president. “Why?” I asked, bristling. I thought he was suggesting that “they” don’t have the same mentality “we” do. No, he explained. From the Palestinian side, he found himself frozen. There was pressure and influence and problems coming from all directions. He’d never before appreciated how difficult and precarious is the situation of a Palestinian leader.

****

If you’re going for true realism, much of military life is boring. Mike tells us that the Convoy Simulator, such fast-paced fun for us, is very boring for the Marines and sailors who use it for training. For 6-8 hours at a stretch, the Marines drive and drive and drive as they practice keeping their Humvees a set distance apart. It’s bad enough if a bomb takes out one vehicle. If you’re driving too close together, it could be two. Drive through the village and back to the base. No insurgents appear on the screen. Hold your weapons ready though most of the time you won’t have any reason to fire. Spot a possible roadside bomb? Stop and call for a security perimeter. Wait.

Staying awake–let alone staying alert–that’s a big part of going to war.

****

The wind howls. The scene is bleak, black and white, and a soldier trudges head down through the snow in the aftermath of a terrible battle.

You are that soldier. Men lie dead and wounded across the field. Some whisper pleas for help. There are bombed out buildings. There’s shelter in the distance and a fire–the warm orange flames the only color in the scene–and your mission is to comfort the suffering, to get survivors to that warmth before they freeze to death. Before you freeze to death with them.

The game, The Snowfield allows you to walk and to pick up objects. That’s all. You can pick up a bottle of whiskey. A rifle (but it seems you can’t fire it). Your movements grow slower and slower and more labored, your footsteps drag the further you get from the fire.

The Snowfield.

The Snowfield.

The action is slow. Very little happens. I couldn’t stop watching.

The scenes are sad, horrific, but the game is created with such an eye to aesthetics, it all has a strange and compelling beauty.

Would a young male used to Call to Duty appreciate The Snowfield?

Could an action game include segments where to advance to the next level you have to slow down, you have to experience boredom, you have to face the ugly aftermath of killing? Of course such a game could be designed but who would bother? Who would market it?

The Call of Duty franchise has sold 139,600,000 games through the year 2013. Admittedly, sales have dropped. In 2013, only 14,500,000 copies of that year’s most recent game were sold.

That’s ten times as many people as actually serve in the US military today.

I look at the empirical study about civil resistance by Erica Chenoweth who was named by Foreign Policy magazine as among the Top 100 Global Thinkers in 2013. Looking at nonviolent social movements worldwide, Chenoweth she found that none failed “after they’d achieved the active and sustained participation of just 3.5 percent of the population.” Doesn’t sound like much. OK, take the US population of approximately 316 million. They means you only have to mobilize a bit over 11 million people. A lot, but fewer than bought the new Call of Duty game in 2013.

3.5% can bring down a dictatorship. What can it do in a country where many people don’t recognize their own oppression?

****

We’ve always known we can’t bomb our way to peace. We have to win hearts and minds. We just can’t figure out how to do it, even here at home.

When I bring up the violently misogynistic content of some games. Ajay Chaudhary suggests the greatest danger is when video games “reproduce social inequalities” by reinforcing stereotypes about identity, race, gender that are part of our daily lives.

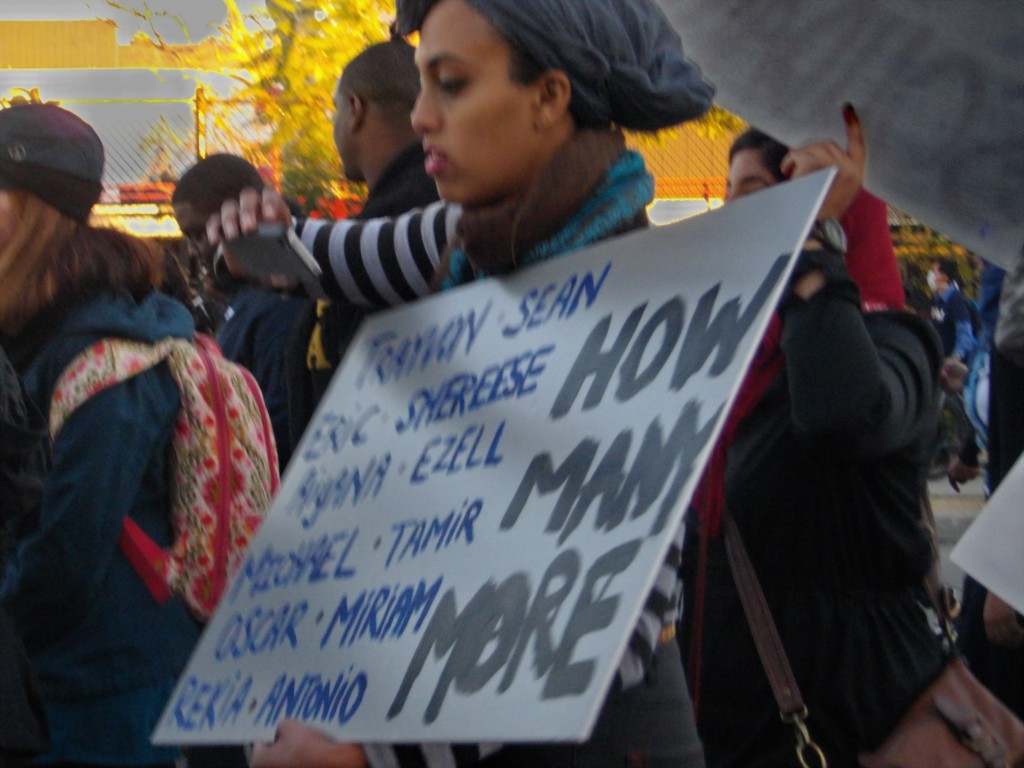

The Stolen Lives Project documents cases of people killed by law enforcement agents. From 1990 to 1999, they collected over 2000 reports from public records. Most of the dead, people of color.

How much patience can we (of the up until now majority community) ask of people who’ve been waiting centuries for equal protection and equal rights and justice?

I want to get rid of the word “waiting,” as though African Americans have stood by passively. They have not been waiting, but rather working for justice, dying for their rights, struggling for centuries.

****

In the year 2000, I had just begun working on a theater project with a Black actor and director named Anthony Lee. A week later, a police officer shot and killed him. A tragic mistake. I was horrified, heartbroken, angry. But I also believe the officer was devastated.

I attended the trial of Johannes Mehserle who shot and killed Oscar Grant. I saw no remorse. There was not a trace in the statements of Darren Wilson. Is it possible they really felt none? Self-appointed security guard George Zimmerman showed us only self-pity. Do our legal system and our polarized society encourage self-justification and the angry refusal to accept responsibility?

When you take a life–justified or not–if you’re not a sociopath, you suffer a moral injury. How can it heal if you are not allowed to feel the guilt and to grieve?

****

At Twentynine Palms, Marines drive through the desert terrain, slowly, 15-35 mph on the alert for roadside bombs. Roads signs are in Arabic as they approach and enter one of three mock Iraqi villages.

At the height of training for combat in Iraq, the Marines hired 1,000 roleplayers– men and women of Middle Eastern nationality or descent–whose identities were closely guarded to protect them and their families from reprisal. They were just intended to be warm bodies providing local color. They were given scripts to follow, but according to Mike, it soon became clear they were needed for much more: to teach cultural competence.

Furnished Iraq interior for practising raids.

Furnished Iraq interior for practising raids.

A Marine goes into a meeting with the town mayor and local notables and within minutes offends all of them.

A Marine passes an Iraqi woman in the street and greets her with a courteous “Good afternoon, Ma’am.” He’s immediately surrounded by a group of hostile Iraqi men, disturbed that an unrelated man has dared speak to a woman.

Surely it’s better to know something than nothing, but how much good did this training do when we were clearly in way over our heads? Marines learn a few words in Arabic, but Mike explains that in Afghanistan there are so many different languages, the military doesn’t even try.

I think of Anand Gopal’s book, No Good Men Among the Living. US misreading of situations and people in Afghanistan had us paying huge sums to dishonest informants, sending innocent men to Guantánamo, jailing Afghan allies because of false reports. However bad you thought it was, read the book and learn it was much much worse.

****

So where do we (the nonviolent movement for peace and justice) find 11 million people?

****

We love action. Video games with cars racing, weapons discharging fire and explosions all happening faster than you can blink. We love kicking down doors and blowing things up.

(But the little boy didn’t ask his father for a weapon!)

This essay is not concise. It meanders. On and on. Will anyone keep reading as I try to think my way forward?

We are addicted to the quick fix. Violence is instant gratification. When you want results NOW, with violence you can cut through the crap, the bureaucratic red tape, the naysayers, the law. But maybe not.

Shock and awe–the bombing of Baghdad by US forces–began on March 19, 2003, the strategy known as “rapid dominance.” We are still there.

Torture. Get a quick answer when faced with an imminent threat. Only the ticking time bomb scenario never actually occurred and torture yielded horrific injustice when we interrogated innocent people with no information to offer and yielded lies and misinformation when we tortured terrorists.

****

CIA apologist Jose A. Rodriguez, Jr. has justified torture again and again by repeating the imminent threat and ticking time bomb scenario. But in his self-serving memoir (Hard Measures: How Aggressive CIA Actions After 9/11 Saved American Lives) here’s what else he says. Of course they knew that people being tortured will say anything. That’s why, he says, they never asked a single question of the prisoners while they were being waterboarded. The “enhanced interrogation techniques” were intended just to break their spirits. Then, during the months that followed, interrogators hung out with the prisoners. Rented DVDs and watched movies and shared popcorn with them, building rapport and garnering bits and pieces of information over the course of months. His own words then acknowledge there was no ticking time bomb. No imminent threat. No justification.

****

Peaceful methods take patience and time and skill. Violence is the quick fix when a person feels bullied, disrespected, ignored. When a person feels sad.

Only violence can resolve matters in an instant. Only it doesn’t.

After 13 years, the US leaves Afghanistan. Mission unaccomplished.

****

You’ve heard of brainwashing. What if brains aren’t washed, but poisoned? By war, exile, oppression. By toxic stress when family members are killed, incarcerated, deployed, deported; by surviving violence, including the violence of poverty and of racism, the mother’s stress hormones flooding over the fetus during pregnancy. The pain of sexual violence, of torture, of being trafficked and sold. The list goes on and on in endless cycles of pain and abuse, pain and retribution. Can we at least stop contributing to the cycle?

Children growing up in some Los Angeles neighborhoods show levels of PTSD comparable to children in Baghdad during the worst violence of the war. But understand: Not every person who’s been traumatized will grow up violent, without impulse control, likely to self-medicate through substance abuse. Can we maximize resilience instead of vulnerability?

We’re talking about millions of people.

Can we re-humanize our society? I talk about nonviolence and compassion but lose my temper on the phone after 40 minutes on hold trying to resolve a simple problem with the bank. What happens when frustration has left many of us numb and deadened till the rage breaks through?

Know Justice, Know Peace.

****

According to Commander John Perez, police officers in Pasadena feel really bad when they have to kill a dog–an attack dog which is also a family pet–in the process of making an arrest. So they tried alternatives. Foam didn’t work. Pepper spray didn’t work. One officer made a suggestion and was laughed at. He tried it anyway. Turns out at least some of the time, a Milkbone will tame an angry pitbull.

Our culture allows–even expects–police to express remorse over dogs. Out of remorse comes the search for solutions. If officers could be as open with their regret over taking human life, would they learn ways to de-escalate situations instead of relying solely on the gun?

****

If we can get rid of “waiting,” I’d also like to get rid of “police brutality.” Certainly we have too many examples of just that, but going after brutal and sadistic cops won’t stop the tragic mistakes, the deaths of Black men like Anthony Lee and like Akai Gurley, gunned down in a Brooklyn stairwell. Or Kendrec McDade, killed by Pasadena police responding to a 911 call that turned out to be false.

The word “brutality” won’t help us correct a culture in which Michael Brown’s family was treated with offhand disrespect, and which teaches central nervous systems to respond instantly, signaling “Danger!” when a Black man comes into view.

Instead of turning their backs on Mayor de Blasio, officers of the NYPD should thank him. By teaching his son how to conduct himself when faced with the police, the mayor protected his son but also made it less likely that a cop will have to carry the lifelong burden of a “tragic mistake.”

****

“Tragic mistake” = the least damning phrase I can offer for the US bombing, invasion, and occupation of Iraq.

****

From the immigrants rights movement I learned a principle, expressed in a slogan: Nothing About Us Without Us. The people most affected must be heard. If we’re going to reform policing, communities of color must be at the table. So must the people who best know what the job requires of them: the police.

****

Gandhi wrote, “We win justice quickest by rendering justice to the other party.”

****

Every small victory proves the oppressive power isn’t omnipotent after all. Every step is one crack in the edifice of unjust power. In the Civil Rights Movement of the Fifties and Sixties, mass marches raised awareness and spirits, created solidarity, forged alliances and suggested the power that might lie behind such numbers. If many white consciences remained untroubled by racism, they were still shocked by the brutal repression of peaceful and dignified resistance. (In those days, unlike now, mainstream media coverage advanced the struggle.) Local campaigns targeted local issues–buses, lunch counters, voter registration. Each local demand was focused but part of something bigger. Each victory, no matter how partial, advanced the larger goal of equal rights and justice without regard to race.

****

Wait a minute. Isn’t that what’s been happening?

****

May Day 2006, millions of immigrants and some of their allies took to the streets in nonviolent protest. No legislation passed. It seemed nothing changed, but as people came out of the shadows, the marches helped organize and mobilize local grassroots organizations and find new supporters for groups that had struggled for decades all over the country. Local groups championed the cause of specific immigrants and convinced judges to use discretion and cancel deportation orders. The young people who became known as DREAMers won executive action that protected them from deportation and allowed them to work. Undocumented immigrants are gaining valid drivers licenses. Some are about to win temporary protection.

Slowing down doesn’t mean waiting. It’s not that sort of patience. It’s about moving forward, step by step.

****

At the annual conference of the National Council of La Raza, panelists spoke about considering everyone a “client”–including the government agencies and entities often seen as adversaries. Instead of fighting them, educate them.

The system won’t come to you. You must go to the system. Department by department, person by person.

I’ve seen examples here in Los Angeles. Here’s just one: Community-based organizations that offer an alternative to incarceration won over people from the D.A.’s office after they gave tours of their facilities and programs to show their effectiveness and share information about what they do. Of course it helps that we elected a new, very receptive D.A. Now Jackie Lacey’s office plays a role in educating hundreds of prosecutors, judges, and even defense attorneys who’ve had no idea what might be possible.

Vote in local elections. D.A., Sheriff, School Board may matter to you more than Congress or even the President.

****

On Monday evenings, leaders from the National Day Laborer Organizing Network bring Latino musicians to the street in front of the Metropolitan Detention Center. They serenade the immigrants locked up inside the building awaiting deportation proceedings, offering solidarity and a little joy while commuters, watching the scene from the elevated Gold Line, learn just what is going on in that strange edifice downtown.

[youtube]https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=IeEOcFsw6_A[/youtube]

So, music. I remember the Freedom Songs of the Civil Rights Movement. Rhythm is the heartbeat. Voices raised together in song create a force.

****

At the grassroots, people agitate. Allies in law, the faith community, professionalized nonprofits don’t take the lead, but stand in solidarity, lobby, negotiate.

****

I’m sick and tired of marching. There are other ways I can offer my support. No more shifting from foot to foot for an hour or more waiting for the damn thing to get underway. Of the self-anointed leaders shouting through bullhorns and giving each other adulatory introductions. Of every fringe group in existence showing up to push every conceivable agenda.

But then I’m on the phone with Laurie Cannady, educator, Army vet, and author whose memoir of girlhood in the ‘hood–Crave: Sojourn of a Hungry Soul–will be published this year. We’re talking about Ferguson and about Eric Garner and she is convinced this is the tipping point. There’s a new Movement now and we’re going to see change. I’m skeptical. Where was the change after Trayvon? Oscar Grant? Anthony Lee? And now, months later, will we have reached that elusive tipping point with Walter Scott?

I Can’t Breathe shirt to protest the death of Eric Garner.

I Can’t Breathe shirt to protest the death of Eric Garner.

****

Laurie came to mind when I heard through social media about a nonviolent march scheduled for December 27th in the streets of LA to protest the killing of unarmed Black Americans. I’d never heard of the organizers. Turns out they keep a low profile not because they have anything to hide but because they are committed to an organization based on We, not Me.

At the Millions March LA.

At the Millions March LA.

The march starts with thousands of people, on time, at the scheduled hour of 2:00. The 500 of us who want to join in conversation arrive at noon, seated in an amphitheater, not shifting foot to foot. It turns out to be a youth-led movement, almost everyone under 35. We meet each other, listen to poetry and spoken word and song, not speeches, though we are given rules: No aggressive language, no F the police. No leafletting, no soliciting, no outside organizations. We’re here, said a speaker to “promote healing, peace, and love in order to process pain and anger and turn it into effective action.”

I wish Laurie could see this. I can see 3.5% now within reach.

We set off, chanting, and I think I’ve gone about this all wrong, looking for excitement, adrenaline. Having fun is just one way to feel alive. There’s something about fun and games–purposeless frivolity–that breaks through the constraints and tedium that weigh us down and trap us in so much of daily life. But purpose–being engaged and interested, committed and active–is every bit as enlivening.

Hands up! Don’t Shoot!

Millions March LA.

Millions March LA.

I used to imagine people marching in silence. Yes, we want to raise our voices and be heard. But I always thought if you could get a mob of people to stay silent, that would be an extraordinary show of discipline and power. That would send a message of serious, unwavering intent. I never thought I’d see it till we stopped and observed 4-1/2 minutes of silence to mark the 4-1/2 hours that Michael Brown’s body was left in the street. At the end of the almost 3-hour march, we stood together, no chants, no shouts, no drums, no bullhorns, no words. We stood together sharing a powerful silence.

****

When you play a game, I think, anything can happen. Same with being part of a Movement. You can’t predict the outcome but you play to win.

—Diane Lefer

.

.

Diane Lefer‘s latest book is the novel, Confessions of a Carnivore, an antic romp through the minefield of recent US history. With her colleague Hector Aristizábal, she wrote and produced Second Chances, a play in which torture survivors and their family members, now rebuilding their lives in Los Angeles, performed their own stories. She is currently posting survivors’ oral histories–as they give permission and remove details that could put them or their families in danger–and she invites readers to visit http://secondchancesla.weebly.com/

Douglas Crosbie, Lynn’s father, reading to her and her baby brother James.

Douglas Crosbie, Lynn’s father, reading to her and her baby brother James.