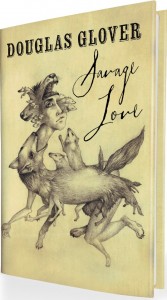

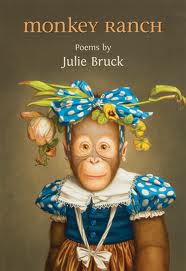

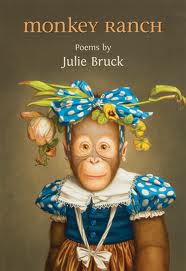

Julie Bruck won the Governor-General’s Award for Poetry last year for her third collection MONKEY RANCH. She is from Montreal but lives in San Francisco. Her other two books (all three published by Brick Books) are THE END OF TRAVEL (1999) and THE WOMAN DOWNSTAIRS (1993). Herewith NC offers a wonderful interview Julie recently gave NC’s Contributing Editor Ann Ireland plus a trove of poems. By mysterious Fate or Synchronicity or sheer Coincidence (still astonishing) it just so happens that Julie Bruck will be reading in Fredericton (where dg is the Writer-in-Residence at the University of New Brunswick, in case you’ve forgotten) Saturday and Sunday at Ross Leckie’s famous Poetry Weekend. According to the latest reading schedule (there is a cast of dozens it seems; never so many poets in once place—difficult to organize; a veritable extravaganza of poets with a huge party at Sharon McCartney‘s house where DG will partake of the Barking Squirrel), Julie Bruck will be reading at Gallery 78 Saturday at 2pm and again at 8pm on Sunday at Memorial Hall.

dg

§

Ann Ireland: Your poems slow the reader down so that we pay attention to moments that might fly by, unobserved. In your first book the poem CLOSURE feels like a statement of poetic intent. Thoughts on this?

Julie Bruck:

CLOSURE

Who hasn’t had days when the door

stayed ajar; the important business call

in which you meant to sound brisk

but goodbye came out bye-bye?

Or when you talked over someone

saying what they’ve tried for years

to say; hung up in the middle

of I love you, or got hung up on.

A plane takes off and a small child

turns from the cloud-streaked

window, asks, what happened?,

and sobs for the rest of the trip.

Poof!–gone are her grandfather’s

delicate nose-hairs, the sunlit world

with its parking-lot demarcations.

There’s just this terrible shaking

between the past and future.

You want to know when it stops.

There’s a poem I haven’t thought about in a long time! When it was written, circa 1990, I wouldn’t have pegged the poem for an ars poetica, but you’re definitely on to something. I’m a person who mourns for what has yet to be lost, for whom the concept of “closure” is laughable. I refuse to come to terms with how provisional and temporary life is. Is that a form of arrested development? I suspect so. Meanwhile, looking slowly and clearly at even the smallest things is an attempt to wrest a snippet of meaning from the passing moment, or to restore the dignity or beauty—even the embarrassment—inherent in what can be so ephemeral.

If I revised that poem today, I’d change “delicate” to “wiry,” a more concise word for how an old man’s nose hair looks to a child. I’m starting to understand why poets like Stanley Kunitz and Donald Justice kept changing and reissuing their early poems in their late years. I’d also cross-examine those semi-colons. But please, stop me before I start. What a slippery slope.

AI:You write of place, of growing up in Montreal. How did it affect your writing to move to San Francisco?

JB: I have a long, intimate connection to Montreal, the kind you don’t get twice in one lifetime. It took almost a decade before I felt like I lived in San Francisco, as seductive as this place can be. When I was new to the Bay Area, I once complained to (the poet) Heather McHugh about homesickness, and she said something to the effect of, you never leave where you come from, you simply carry it with you. At the time, this advice sounded more like one of Stuart Smalley’s Daily Affirmations on Saturday Night Live, but Heather, who also has roots in Canada, is the smartest person I know. Sure enough, as both cities took up residence in my writing, I came to feel both more grounded in California and more connected to where I’m from. That was an enormous relief, though I should have had more faith: so many writers whose work I admire retain a creative foot– if not both feet–in their place of origin. James Thurber said, “The clocks that strike in my dreams are often the clocks of Columbus.” My chimes will always be the CBC’s “long dash, followed by a period of silence,” though I’m beginning to take comfort in the emergency siren that sounds here every Tuesday at noon, with its warbling reminder that “this is just a test.”

AI: How might you describe your upbringing, the household you grew up in?

JB: Idyllic and fraught. My dad, who died just days before his 98th birthday this March, was the president of a textile company when there still was a large domestic textile industry in Canada, so our family was quite affluent. I grew up in a big Georgian greystone in Westmount, and my two older brothers and I went to a private school a few blocks away. By the time I was nine, my brothers had left for colleges in the U.S., and their absence had a big effect on me, though I didn’t know it at the time. On one hand, I gained a great deal of solitude in the big house (a state I still crave today), and on the other, I became an only child, wedged between my parents, absorbing the dissonance from two well-meaning people who never should have married. My father was, despite his liberal politics and fascination with Thomas Jefferson, very traditional in his family expectations, while my mother wasn’t one for the bell jar. While my dad would come home wrung out from dealing with budding labor unions, my mother was organizing anti-poverty or clothing drives on behalf of the children of these very same people. So, while I enjoyed all the pleasures that my father’s work brought us, I also received a clear message from my mother, which was that our largesse was built on someone else’s labor. Something was always rotten in the state of Denmark, and I began to look at things from a slight remove, a stance I still have. These particular family matters are things I’d just begun to revisit in Monkey Ranch, and I don’t think I’ve quite exhausted them, as my long answer to your question suggests.

AI: When did you start reading poetry? Were you read poetry as a child? Which poets first excited you?

JB: My mother read Edward Lear and other children’s verse out loud when I was little, and my father liked to quote Ogden Nash, but aside from a voracious appetite for British children’s mysteries with ponies in them, I never became an enthusiastic young reader. My parents loved to read, and this may have been a reaction, I don’t know. I do know that I wanted to be outside, preferably with real animals instead of imaginary ones. It wasn’t until my early 20’s that I started to read actively. Those were tough years, and I was looking for meaning and excitement wherever I could find it. I read lots of Canadian women poets, especially Atwood. I had much reading ahead of me. If I’d known how much, I might have fled for the hills.

AI: You began training as a visual artist. What caused the change in direction? Do you still make visual art or is your highly visual poetry taking care of that?

JB: After a few years of photography, using both 35mm and large format cameras, I was frustrated with needing so much equipment to make such quiet, simple things. I’d just completed my freshman year at The San Francisco Art Institute, and the little kitchen in my apartment doubled as a darkroom. Since I was using traditional archival methods, one day it dawned on me that I was probably washing my fruits and vegetables in selenium toner or gold chloride. To make a long story shorter, the simplicity of a pen and a notebook looked good. And of course, poetry is another way of framing what one sees, one that uses revision instead of dodging and burning to fill in the shadows and set the brightness, the contrast, the tensions in the work. There are plenty of kinships between the two mediums.

This week, I stumbled across a familiar bright orange box at the local thrift shop, the same rare, soft Agfa portrait paper I used to use. Someone had ripped open the light-proof black wrapping inside the box–to inspect the contents, I guess–exposing and ruining every sheet. I stood there for a few minutes, feeling very sad and very analog.

I still have my Olympus OM-1, but it needs repair, which is both hard to find and expensive. Eventually, I’ll have it fixed, even if I take the film to Walgreen’s, and have the images digitized.

AI: How is the writing scene in Montreal different from SF?

JB: Montreal’s Anglophone writing scene is very small and intimate, while the Bay Area’s writing “communities” are multiple and widely scattered. In a way, they mirror the topography here, which has scores of neighborhoods folded into these dramatic hills. If you chose to, you could attend a literary event every night in San Francisco, and never touch down, but it would be hard to get any work done.

AI: Did you know any writers when you moved to SF?

JB: My spouse, Lewis Buzbee, is a writer and a third-generation Californian, so I got to know local writers through him. I’ve also made writerly friends on my own here, but much of my writing life remains tied to Canada, and I still exchange work with friends in Montreal. I was 40 when I picked up stakes, and these old affections transcend geography. They’re akin to what Leonard Cohen lovingly refers to as his “neurotic affiliations” in Montreal. They run deep.

AI: Advantages to having a foot in Canada and the USA. Any disadvantages?

JB: Quite honestly, I never plan much according to practical advantages and disadvantages, for better and for worse. I’ve just followed my dumb heart so far. Except for parenthood, which changes everything, my daily life here isn’t so different from what it was in Montreal. Like most writers, I struggle to carve time from work and other responsibilities to get a few quiet hours to work .

I sometimes wonder whether living in San Francisco isn’t more like being in Oz than living in the U.S. It’s such a left-leaning, progressive place, it’s easy to lose sight of the rest of the country from here. Meanwhile, growing up as an Anglophone in Quebec might have been the perfect training for living a bit of a split existence. I can just add one more hyphen. When I lived in Canada, I had a foot in the States. Now I have a foot in Canada. When you come down to it, isn’t that how most writers live–with one foot in the immediate surround, and another inside the work that goes on in their heads? Ugh, I’m mangling this metaphor so badly, I should have to walk around with a foot in my head.

AI: What kind of work do you do in SF?

JB: For nearly nine years, I’ve taught year-round poetry classes for adults at The Writing Salon in the Mission district, as well as working privately with a few individual writers. During the academic year, I also tutor part-time at The University of San Francisco, and pick up various freelance gigs. This is an expensive city, and we have a teenager, so I scramble a fair bit.

AI: Thoughts on teaching poetry? What is it that you teach your students?

JB: If there’s one thing I try to convey above all else, it’s the importance of breaking the tyranny of pre-determined subject matter, just enough to allow for real discoveries to happen in the writing. This is something I’ve had to learn and relearn myself, and each time I “relearn” it is an exhilaration.

Many beginners–and not just a few seasoned writers–feel that they can’t write without that familiar pressure in the chest, the one associated with something particularly painful in their lives. They’re carrying such a heavy biscuit when they sit down to write, it’s no wonder they avoid their desks. What I try to teach, and it’s often a challenge since we’re so often bound by our versions of “what actually happened,” is that whether you’re exploring metaphor by writing from the point of view of a lychee nut, or taking on the challenges of some new and unfamiliar form, it’s the engagement with language that matters most. If divorce is on your mind, that lychee nut might be cleaved, that delicious word that means both torn apart and joined, and what would that suggest about separation and loss? Maybe a villanelle’s patterns of repetition won’t narrow your possible word choices, but actually expand them, pointing to a word you’d never have considered, but which couldn’t be more apt. These kinds of playful engagements are, I think, the best ways to discover meaning you couldn’t have predicted, and to make poems that are fresher, deeper, and more relevant to the reader. In that state of mind, your heart rate goes up just reading the dictionary. You come to realize that your angle of approach can vary wildly, but your own themes will always surface, and that no-one’s going to take away your voice.

Hmm, I notice that the teacherly “you” has infiltrated this conversation.

AI: How has your work changed in form and content over the three books?

JB: I hope the work has become more expansive. Some poems from the first two books might confuse precision with depth, though I’m likely not the best judge of that. The books span 20 years. I’ve grown older, had a kid, and the newer poems should, to steal a photographic term, have a wider angle of view. Teaching has also been helpful to me as a writer. I decided early on that I couldn’t impose anything on my students I wasn’t willing to try, and I think that kind of playfulness, coupled with the game exuberance I see in so many of my students has tempered a streak of preciousness in me. It’s made the writing more fun.

AI: You’re not prolific ( I should talk)—can you talk about your writing process?

JB: Yes, I’m awfully slow, but most of that has to do with being an ardent reviser. And often, it’s only when I see the shadow of a manuscript emerging from what had been just a stack of drafts, that I can finish certain pieces, since the revisions involve not only what’s on that particular page, but how that poem might interact with its new neighbors, in its new town.

AI: Thoughts on traditional poetic forms and metrics? How important is sound?

JB: I like the constraints of traditional forms, and the surprising ways those limitations can be freeing, but I’ve only included a few loose sonnets in my books. That may change in the next collection, since I’m having a good time with certain fixed forms at the moment.

Sound matters a great deal. Free verse is really just variations on basic iambic pentameter (I hate to see de eve’nin sun go down—ta-dum,ta-dum,ta-dum, ta-tum,ta-dum–the sound of our heart-beats), and patterns of stress are an essential part of a poem’s tension and meaning. I’ve never written strict metrical verse, but my ear is tuned to where the stresses fall in a poem, as well as to alliteration, assonance and consonance, and to how line breaks manipulate sound.

AI: How does a poem gather in your head?

JB: A poem can begin almost anywhere, but the most common scenario starts as an itch that I can’t quite scratch. There might be two or three seemingly unrelated images or bits of conversation or musical phrases, and an intuition that these things are connected. The real work lies in finding that connective tissue, and in the process, discovering why this particular poem wants to be written, what gesture it wants to make. I once heard Robert Pinsky describe some poems in terms of their “infinitives.” He looked at several pieces for the particular movement or gesture in each one; to seek, to lament, to persuade. That’s an approach I’ve found to be very helpful, as long as I don’t close in on the poem’s infinitive too soon, and exclude other possibilities the poem may hold. I always want to let the poem lead, and I think a reader knows when a writer has wrested control of the thing too early. Those poems feel predetermined, as if the writer has decided the poem’s an elegy, while the poem itself feels resistant –like it really wants to blow the deceased’s cover.

Very rarely, a finished poem just lands in my lap. But those usually come when I’ve been working hard on thorny pieces, or ones I’ve had to abandon. I no longer stand around waiting for lightning to strike. Life’s too short.

AI: Do you see yourself as having a ‘poetic project’ that continues as a through- line in your books. What is it that you seek to engage with, to investigate over the years?

JB: Probably, ibid: That life’s too short. Occasionally, I’ll concoct grand plans for what’s next, but in the end the work seems to create its own path. I have to trust that there’s more than one note to be struck concerning the fact that we’re temporary–I think the history of literature certainly bears that out–and that those notes can also be ones of dark humor, and even joy.

AI: In Monkey Ranch: “Snapshot at Uxmal, 1972,” you fix on what appears to be a photograph of you as a teenager with your photographer mother. Mother pays attention to detail in her work, lots of zoom lens; father speaks of the – ‘vast scale of what he saw while heading off to visit larger ruins.’ You remark on the teenager in the photo: ‘Her father’s impatience hasn’t flared in her yet, / though she carries that too, an unstruck match.’ Care to comment?

JB: That poem arose from coming across a photo I’d taken of my mother, resting against a temple wall with her cameras. At fifteen, I was heavily identified with her. I would never have guessed that aspects of my father I also carried–his single-mindedness among them–were the very things that would let me differentiate myself from her later on. When a child acts as a buffer, or a compensation for a shaky marriage, growing up and away can feel like a betrayal of that close parent. It can also anger the more distant parent, who needs the child to fill in for them emotionally, and that creates additional pressure on the kid.

That’s a lot of baggage for such a little poem to carry. I hope the reader doesn’t need all that information to feel the latent tension between a mother and daughter, but it is what underlies the “unstruck match.” A lot of young people feel they are responsible for maintaining their family dynamic, and that opting out of their assigned role is tantamount to setting fire to the family.

AI: I note several references to Elizabeth Bishop. How has she influenced your thinking and writing?

JB: I’ve been reading Bishop for many years–the poems and prose, all her collections of letters, and every biography out there. In truth, I have no idea whether my great affection for her work has had any direct influence me or not, but I’ve often felt changed as a person by reading her. What I love best about her poems is how the emotional pressure of what’s left unsaid seeps through. All she has to do is describe that greasy little doily or the “hirsute begonia” in her poem “Filling Station,” and I’m awash in both beauty and loneliness.

AI: Do you need any particular circumstances to be able to write?

JB: An empty flat is best but very rare, so I use the circumstances at hand. At the busiest times of the year, I have a standing, weekly writing appointment with my notebook in a parked car. As long as words get put down on a regular basis, I can live with myself, and I suspect this makes me easier to live with. I had a residency at The MacDowell Colony many years ago, and I’ve kept a little essence of that kind of stillness tucked away inside. When I need it, I pour out just a few drops. A tincture of quiet. One day, I hope to get back there and refill it for the next decade or two.

AI: Which poets should we read, dead and alive?

JB: I’m a promiscuous reader, so I’ll narrow it to (mostly) living writers in my country of residence. I have two current enthusiasms. The first is for what the Buddhists call “monkey mind,” meaning poems that dramatize the movement of mind, with all those meanderings and loop-de-loops, though never at the expense of clarity and communication. This would include work by Lucia Perillo, Bob Hicok, Paul Muldoon, Jim Harrison, Nikki Finney, and C.K. Williams, just for starters.

A second excitement comes from poems that compress and distill, and here I think of Charles Simic, Kay Ryan, Rae Armantrout and Jane Kenyon. Of course, this excludes poets who do both. It’s an impossible question, and if we throw Canada in the mix, I’m overwhelmed. Suffice to say, I can’t wait to get my paws on a copy of Sue Goyette’s new book, “Ocean.”

AI: Californians are very outdoorsy, hiking and camping etc. You?

JB: Such a waste! I’m an urban creature, happy with daily walks or runs in Golden Gate Park. Occasionally we leave the neighborhood to be astounded by the natural beauty of the state, but at heart we are city rats. You don’t really need to leave San Francisco to feel connected to nature. We have the shoreline of the Bay, the Presidio, Crissy Field, all the boats, and the fog blowing in and out. In our neighborhood, the fog tends to be in, which lends a winterish character to the summers.

AI: What music do you listen to? You refer to Richard Thompson a couple of times in your work.

JB: I’ve always been a devoted fan of Richard Thompson, both as a guitarist and songwriter, and there are other singer-songwriters on my list (Patty Larkin, high among them), but my own playlists have been eclipsed by my 15-year-old’s . She has the vinyl collection, and the biggest speakers in the house. That means I hear a lot of Vampire Weekend and The Vaccines, among others. Hardship? I think not.

— Ann Ireland & Julie Bruck

§

Poems from Monkey Ranch

/

THIS MORNING, AFTER AN EXECUTION AT SAN QUENTIN

[SPACESPACE]My husband said he felt human again

after days of stomach flu, made himself French toast,

[SPACESPACESPACESPACESPACE]then lay down again to be sure.

[SPACESPACE]I took our daughter to the zoo,

where she stood on small flowered legs, transfixed by the drone

[SPACESPACESPACESPACESPACE]of the howler monkey,

[SPACESPACESPACESPAC]a sound more retch than howl.

[SPACESPACE]Singing monkey, my girl says.

She is well-rested. We all are. As we slept, cold spring air arrived,

[SPACESPACESPACES]blown from the Bay where San Quentin

[SPACESPACESPACESPACESPACE]casts its sharp light.

[SPACESPACE]Tonight, my girl will tell her father

(a man restored, even grateful, for a day or so), about what she

[SPACESPACESPACESPACESPACE]saw in the raised cage.

[SPACESPACESPACESPACE]Monkey singing, she will tell him,

[SPACESPACE]and later, tell every corner of her cool dark room,

until the crib springs ease because she’s run out of joy,

[SPACESPACESPACESPACESPACE]and fallen asleep on her knees.

/

SPACE

SNAPSHOT AT UXMAL, 1972

Leaning into the sun-warmed stone, she must

be fifty, still beautiful, her strong frame

easy inside her loose shirt and jeans.

He’s gone to a larger ruin for the day,

someplace deeper in the jungle, more

challenging to reach by jeep or tank.

Here, where the early Mayans worshipped

the sun, appeased their gods with routine

live sacrifice, she will photograph only

small details in black and white. Later,

he’ll describe the jungle’s colours, ornate

bird plumage, the vast scale of what he saw.

She will need the afternoon to document a single

weed growing through a crack in the pediment,

a candy wrapper blown against an ancient step.

And there is the daughter, fifteen and not

quite as sullen as she’s going to be, shouldering

the pack of lenses, her mother’s fine-grain film.

Her father’s impatience hasn’t flared in her yet,

though she carries that too, an unstruck match,

trailing her mother through the tall, dry grass.

/

SPACE

LIVE NEWS FEED

I am watching my mother’s neighbourhood

explode on live TV, when Ruth, my father’s

girlfriend, calls from her renovated kitchen,

reports she is baking an apple cake.

On screen, one more disaffected youth

in a trenchcoat, and bodies–trauma units

filling up fast with the dead and injured.

My father is 92, she is ten years younger.

They live in her B.C. apple orchard

after a twenty-five-year affair, which

somehow slipped under everyone’s radar,

lasting half of my parents’ marriage.

Are you watching the news? I ask.

Yes, she says, terrible isn’t it?

If I’d been able to speak, I would

have said, Yes Ruth, I haven’t reached

my mother: perhaps she’s dead.

But my father needs to talk

about an insight he’s gleaned

from a Steinbeck novel-on-tape.

I ask whether he’s seen the news.

Awful, isn’t it? he says,

and returns to East of Eden.

It is already dark in Montreal.

Blue police lights bounce on wet

streets and buildings I knew better

than my own hand, everything

cordoned with yellow crime-tape.

Once, I’d thought we’d all driven

my father away: conversation at the family

table was fast, digression the rule.

He’d often dozed off by dessert.

Guns drawn, a SWAT team flanks

the door to my mother’s building.

My father wraps up Steinbeck, inquires after

my health, says their kitchen smells good:

Ruth took those apples from the neighbour’s orchard.

She swears stolen apples have more flavor.

/

SPACE

OCEAN RIDGE

I used to watch my supple mother

bend to collect shells on the beach.

They piled up on the porch furniture–

she rarely threw anything back.

Look at how the water’s made

a Henry Moore hole in this one

she’d say, look–but I didn’t want

to be told what to look at, how to see,

didn’t want her using my head as

a spare room for her own, a self-

storage unit, though I couldn’t have

said so then, not even to myself.

Instead, I’d get a knot in my chest

that tightened on cue, I’d darken.

Now, when I gaze at my daughter,

she raises her eyes to mine in defiance:

Stop looking at me, she’ll growl, and why

am I surprised? I was looking at her brave brow,

the profile that’s her own and no-one else’s,

because yes, she’s a physical extension

of her father and me–I’m looking at what

we made, and she knows this in her marrow, puts

on her 100-yard stare and turns her face away:

all I can see is the tip of one ear,

sunlit almost to transparency,

its delicate runnels and inlets

shaped, as if by water.

/

Poems from End of Travel

/

SEX NEXT DOOR

It’s rare, slow as a creaking of oars,

and she is so frail and short of breath

on the street, the stairs–tiny, Lilliputian,

one wonders how they do it.

So, wakened by the shiftings of their bed nudging

our shared wall as a boat rubs its pilings,

I want it to continue, before her awful

hollow coughing fit begins. And when

they have to stop (always), until it passes, let

us praise that resumed rhythm, no more than a twitch

really, of our common floorboards. And how

he’s waited for her before pushing off

in their rusted vessel, bailing when they have to,

but moving out anyway, across the black water.

/

SPACE

A BUS IN NOVA SCOTIA

“I felt as if I was being kidnapped, even if I wasn’t.”

–Elizabeth Bishop

Imagine Elizabeth six years old,

being torn from this narrow province,

a train’s headlamp dividing the dark, south-west,

all the way to Worcester, Massachussetts, 1916.

Our bus flies down the same curved road,

past the sign for Pictou County, and a yellow

diamond warning magically of Flying Stones.

The skies are wild and northern. I can still

hear the aggrieved honking of the Canada goose

I disturbed this morning in the Wildlife Management Area,

and now, by the sign ordering us to YEILD

in the late half-light, I almost expect

Miss Bishop’s lonely moose, high as a church,

homely as a house, to appear at the next bend.

Our driver waves to every passing truck.

Their headlights flash across a farmhouse window,

redden the eye of a roadside dog.

One trucker doffs his cap as he roars past,

going home to his invisible house by the water,

where five pennies buys you a great many humbugs,

where the dress was all wrong. She screamed.

The child vanishes. Where the moon

in the bureau mirror looks out a million miles.

/

SPACE

WAKING UP THE NEIGHBOURHOOD

Just back from California this early Sunday,

and now, those introspective singer-songwriters, or Bach,

even the manic genius of Glenn Gould–just won’t cut it.

Outside, in the gentle Montreal morning

of my childhood, an old man shuffles past

on the arm of his paid, young companion.

Pink impatiens do what they do in orderly beds,

as the odd cyclist zips by in black-and-white Spandex

under Sherbrooke Street’s arched maples.

A homeless man, his hand out for change, seems

tentative, even apologetic. In San Francisco,

I heard someone tell a panhandler, ‘Sorry man,

but change comes from within.’ Yes, that’s

a non-sequitur, and neighbours, I’m sorry.

But this moth on the window screen is too grey

and plain to me, after driving the fire-seared hills

of Oakland, after crossing the Bay Bridge

to the city at nightfall, as bank fog moved

like pure violet cataclysm across the navy bay.

Neighbours, this calls for Peter Gabriel,

his overblown synthesizers, overlaid drum tracks.

Neighbours, we live like orderly mice here

atop the Laurentian fault, Precambrian

and deep as the San Andreas. Surely, this

calls for a brighter noise. I’m sorry, neighbours–

you, concert pianist; you, sleepy optician;

you, McGill phys.ed coach with the girlfriend,

here only on weekends–I’m sorry. But the man

I love sleeps on his side in that other landscape,

fog stalled over the city, as Sandburg said, on cat’s feet.

Here, our papers fill with fights over the language

of signs, instead of what they signify. I’m sorry,

neighbours, to wake you from pleasant or anxious

dreams, but the very limestone under your beds

is grinding against itself right now (for God’s

sake, I could have put on Wagner’s marches!),

and this building settled on its foundations

nearly one hundred years ago and trembles

with every bus that goes by. Neighbours,

I’m sorry about all this bass and percussion

so early on a Sunday, but hey–d’you feel that?

/

SPACE

IN CALIFORNIA

At the edge of sleep, I thought it was snow

I heard brush and rattle the bay windows;

the same hour when cars glide soundlessly

down white Montreal streets and the smell

of winter creeps around window frames,

straight under doors into dreams.

But our baby is now the size of a lima bean

and growing fast in this place where winter

means red bottle brushes dangling from trees

and crazy-fragile freesias in street vendors’ buckets.

I must have curled myself around our bean

like a thick seed-coating against the cold,

and I was glad to do so, though when I woke,

way, way down in the bed, small as I could

make myself, what I heard in this clear, indigo

midnight, was the bottle-picker’s progress

among our block’s blue boxes, and it was

a minor miracle that the empties could rattle so

in a grocery cart filling with snow.

— Julie Bruck

———————

Julie Bruck is the author of three collections of poems from Brick Books: MONKEY RANCH (2012), THE END OF TRAVEL (1999), and THE WOMAN DOWNSTAIRS (1993). Her work also appears in magazines and journals like The New Yorker, Ms, Ploughshares, The Walrus, The Malahat Review, Valparaiso Poetry Review, Maisonneuve, Literary Mama, and others, and her poems have been widely anthologized. Her awards and fellowships include, Canada’s 2012 Governor General’s Literary Award for Poetry, The A.M. Klein Award for Poetry, two Pushcart Prize nominations, Gold Canadian National Magazine Awards (twice), a Sustainable Arts Foundation Promise Award, as well as grants from The Canada Council for the Arts, and a Catherine Boettcher Fellowship from The MacDowell Colony. Montreal-born and raised, Julie has taught at several colleges and universities in Canada, and has been a resident faculty member at The Frost Place in Franconia, New Hampshire. Since 2005, she has taught poetry workshops for The Writing Salon in San Francisco’s Mission district, and tutored students at The University of San Francisco. She lives in San Francisco’s foggy Inner Sunset district with her husband, the writer Lewis Buzbee, their daughter Maddy, and two enormous geriatric goldfish. She is currently writing poems for a new manuscript, with the working title of DOMINION.

Ann Ireland is the author of four novels, most recently THE BLUE GUITAR, which has been getting excellent reviews all across Canada. She coordinates the Writing Workshops department at the Chang School of Continuing Education, Ryerson University, in Toronto. She teaches on line writing courses and edits novels for other writers from time to time. She also writes profiles of artists for Canadian Art Magazine and Numéro Cinq Magazine (where she is Contributing Editor). Dundurn Press republished Ann’s second novel THE INSTRUCTOR in Spring, 2013.

Ann Ireland is the author of four novels, most recently THE BLUE GUITAR, which has been getting excellent reviews all across Canada. She coordinates the Writing Workshops department at the Chang School of Continuing Education, Ryerson University, in Toronto. She teaches on line writing courses and edits novels for other writers from time to time. She also writes profiles of artists for Canadian Art Magazine and Numéro Cinq Magazine (where she is Contributing Editor). Dundurn Press republished Ann’s second novel THE INSTRUCTOR in Spring, 2013.

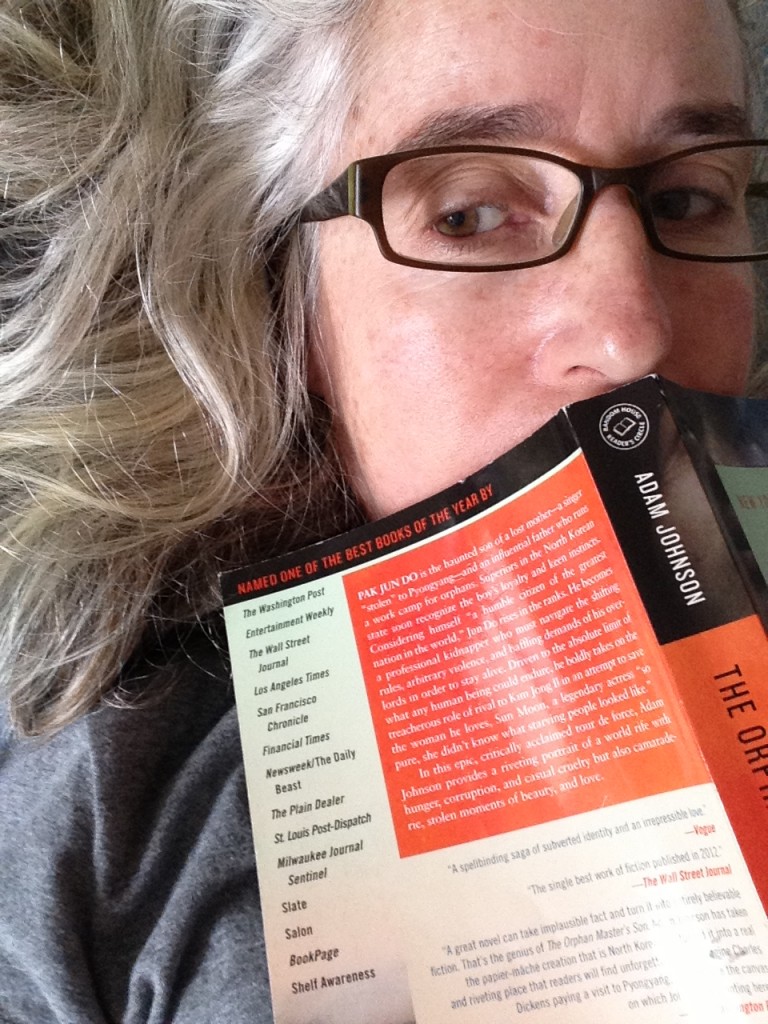

Author photo by the poet’s daughter, Hannah Tarkinson.

Author photo by the poet’s daughter, Hannah Tarkinson.