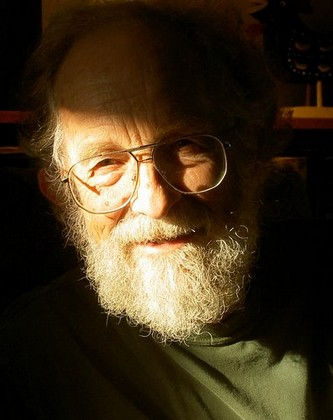

Herewith Betsy Sholl’s diffident, respectful and intensely thoughtful essay on Osip Mandelstam, his life, poetry, and translations. Betsy is a dear friend and colleague at Vermont College of Fine Arts where she teaches poetry and I teach prose and we meet and catch up every six months at the residencies in Montpelier. At once an essay about poetry and about the art of translation, “The Dark Speech of Silence Laboring” plays on the oscillation between intimacy and distance involved in reading poems in translation and ends by celebrating that distance. She writes: “Maybe the sense of lifting one veil only to find another describes all reading, describes our human condition.”

dg

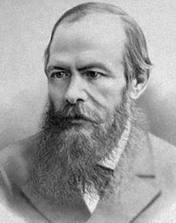

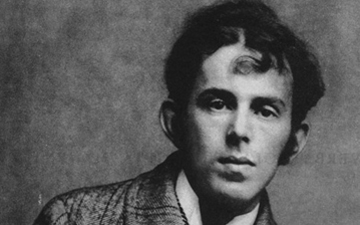

When I ask myself why, for the last several years, I have gone back to the work Osip Mandelstam more than any other poet, the answer seems to involve some combination of the man and his work, or perhaps the man in his work. There is an intimacy in his voice that carries a quality of purity, as if the poems welled up from within and were first whispered to himself as provisional stays against the chaos around him. The words are like boulders allowing him to cross a difficult river, one bank being his own interior life, the other the outside world of Soviet life. Even in translation the intensity of his language comes through, a sense of the physicality of his words, an almost palpable voice. His genius for metaphor is clear: in the rapidity of association images have that quality of transformability or convertibility, which he admires in Dante, whose “similes that are,” he says, “never descriptive, that is, purely representational. They always pursue the concrete goal of giving the inner image of the structure or the force… (Conversation about Dante).” To suggest something of the original quality of his mind, here is a prose description from Journey to Armenia:

I managed to observe the clouds performing their devotions to Ararat.

It was the descending and ascending motion of cream when it is poured into a glass of ruddy tea and roils in all directions like cumulous tubers.

The sky in the land of Ararat gives little pleasure, however, to the Lord of Sabaoth; it was dreamed by the blue titmouse in the spirit of the most ancient atheism.

There is in the passage, of course, the delicious metaphor of clouds like cream in tea. But there is so much more. Ararat is the mountain where Noah’s Ark is said to have landed, which suggests a world in dubious straits—some element of survival surrounded by vast destruction. If the Jewish God is one of justice and order, then the roiling clouds suggest a kind of airily chaotic movement in contrast to the rest commanded by the “Lord of Sabaoth.” I don’t fully understand the blue titmouse, but it seems that this resting place, this starting place for the new order of life is still in tension with something older, wilder, not to be easily subdued. Clouds like tubers, descending and ascending, atheism and the blue titmouse—God seems hardly able to control the world he has been trying to get right!

Though Mandelstam conveys a kind of interior landscape that can seem very private, nevertheless the poems are deeply engaged with culture and history, registering the rapid changes in the world around him. The poems work with interior images, like much lyric poetry of our current time, but Mandelstam does not merely depict his own sensibility; he takes all the resources of lyricism and uses them to address the world around him.

For several reasons the poems can be difficult. Some have to do with our ignorance of Russian culture and history: we miss the lines of other poets embedded in his own, and many subtle allusions a Russian reader would recognize. Other references and associative leaps come from such a deeply personal place, the best we can do is catch the resonance, the dust flying off his boot soles. His widow Nadezhda Mandelstam sometimes argues against accepted interpretations of certain poems, as though even Russian scholars have missed private allusions. In his “Conversation about Dante,” Mandelstam himself compares the rapidity of poetic association to running across a river, “jammed with mobile Chinese junks sailing at various directions.” He continues, “This is how the meaning of poetic speech is created. Its route cannot be reconstructed by interviewing the boatmen: they will not tell how and why we were leaping from junk to junk.” So we make our way, leaping, stumbling. Despite the difficulties and the problems of translation, Mandelstam’s emotional openness and vulnerability clearly come across.

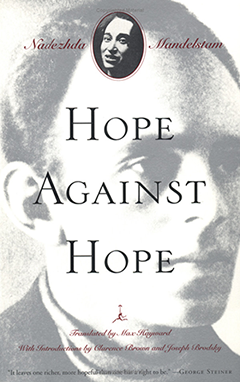

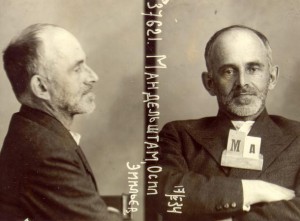

And that brings me to the life. Mandelstam was born in 1891, and came of age during the revolution with its various conflicting parties, its terrorism and deprivations. I won’t spend time here on biography or Russian history—those things are easy enough to find. Suffice it to say the aftermath of revolution was chaotic with various leaders in and out of power, endless atrocities. In the mid ‘20s Stalin rose to the top. By 1930 he had published a letter announcing that “nothing should be published that was at variance with the official point of view.” In 1933, as if silent acquiescence had become intolerable, Mandelstam composed his famous “Stalin Epigram” and read it to at least two different gatherings, clearly aware someone would probably turn him in. Nadezhda Mandelstam, in her memoir Hope Against Hope, says in doing this, he was “choosing his manner of death.” Perhaps the real crime, and for Mandelstam the real necessity, was what she calls “the usurpation of the right to words and thoughts that the ruling powers reserved exclusively for themselves….” At any rate, it was like signing his own death sentence, which Mandelstam himself suggested in a kind of recklessly sanguine moment when he said to her, “Why do you complain? Poetry is respected only in this country—people kill for it. There’s no place where more people are killed for it.” In Mandelstam’s case, he was jailed, interrogated and eventually exiled for three years, from 1934 to May of 1937, then arrested again in May of 1938, and sentenced to hard labor. He died in a transit camp in Eastern Siberia that December. Here’s the poem in Merwin’s translation:

And that brings me to the life. Mandelstam was born in 1891, and came of age during the revolution with its various conflicting parties, its terrorism and deprivations. I won’t spend time here on biography or Russian history—those things are easy enough to find. Suffice it to say the aftermath of revolution was chaotic with various leaders in and out of power, endless atrocities. In the mid ‘20s Stalin rose to the top. By 1930 he had published a letter announcing that “nothing should be published that was at variance with the official point of view.” In 1933, as if silent acquiescence had become intolerable, Mandelstam composed his famous “Stalin Epigram” and read it to at least two different gatherings, clearly aware someone would probably turn him in. Nadezhda Mandelstam, in her memoir Hope Against Hope, says in doing this, he was “choosing his manner of death.” Perhaps the real crime, and for Mandelstam the real necessity, was what she calls “the usurpation of the right to words and thoughts that the ruling powers reserved exclusively for themselves….” At any rate, it was like signing his own death sentence, which Mandelstam himself suggested in a kind of recklessly sanguine moment when he said to her, “Why do you complain? Poetry is respected only in this country—people kill for it. There’s no place where more people are killed for it.” In Mandelstam’s case, he was jailed, interrogated and eventually exiled for three years, from 1934 to May of 1937, then arrested again in May of 1938, and sentenced to hard labor. He died in a transit camp in Eastern Siberia that December. Here’s the poem in Merwin’s translation:

THE STALIN EPIGRAM

Our lives no longer feel ground under them.

At ten paces you can’t hear our words.

But whenever there’s a snatch of talk

it turns to the Kremlin mountaineer,

the ten thick worms of his fingers,

his words like measures of weight,

the huge laughing cockroaches on his top lip,

the glitter of his boot-rims.

Ringed with a scum of chicken-necked bosses

he toys with the tributes of half-men.

One whistles, another meows, a third snivels.

He pokes out his finger and he alone goes boom.

He forges decrees in a line like horseshoes,

one for the groin, one the forehead, temple, eye.

He rolls the executions on his tongue like berries.

He wishes he could hug them like big friends from home.

[November, 1933]

This poem is more accessible than most of Mandelstam’s poems, which suggests he felt his fate closing in, and wanted to make his position clear, leaving nothing to ambiguity. Certain lines of Merwin’s version are burned into my mind, and I hate to even look at other versions: “the huge laughing cockroaches on his top lip,” “Ringed with a scum of chicken-necked bosses,” “He pokes out his finger and he alone goes boom.” However, if we look at the Hayward translation, which is the one printed in Hope Against Hope, there is “the broad-chested Ossette,” and that reference is clearly in the original. Apparently there was some question about whether Stalin was actually from Georgian or Ossetia, the small republic next door. Ossetians were viewed as less refined and more violent, so Stalin officially claimed to be Georgian. It’s telling to consider that even as Mandelstam recited the poem, knowing the dangers, he was concerned with its artistic quality, and said he wanted to get rid of those last lines, they were no good. Perhaps Merwin was wise to avoid a reference the poet himself questioned, and that wouldn’t mean much to English readers anyway. The “berries” in Merwin are raspberries in the original, which apparently is gangster-speak for the criminal underworld. It is clear from just these little points how compacted a Mandelstam poem is, even one of his most accessible. Joseph Brodsky has said that this “overloaded” quality of his verse is what makes Mandelstam unique. (For the most part he worked in traditional forms—rhyme and iambic meter.)

Given our experience in America, where poems, cartoons, rants on just about everything go into the blogosphere with no repercussions, it may be good to stop a moment and realize the nature of Soviet life. The closest parallel in our times might be the fundamentalist extremism of certain theocracies. In Soviet Russia the state controlled everything—work, housing, food. Arrests, sentences of hard labor or exile, executions were ongoing. Currying favor was basically the only way to have any kind of bearable life—a place to stay, enough work to survive, ration books for food. Many intellectuals and artists caved, turned in fellow writers, wrote what would get them the few benefits available, or else they sat out the terror in silence. So, what made it possible for Mandelstam to speak out? He chose to respond to Stalin as a poet, in a poem read to other poets, so I wonder if there is something in his concept of poetry that contributed to his ability to resist what Nadezhda calls “a rationalist program of social change [that] demanded blind faith and obedience to authority.” Of course there are many factors separate from poetry involving background, education, character, a whole complex belief system. But there must have been something in his understanding of poetry and its place in the world that contributed as well.

For one thing, with his fellow Acmeists he rejected the Russian Symbolist emphasis on a form of subjectivity that considered the poet a superior being, whose poem was significant only in so far as it was the vehicle for the poet’s statements. For the more extreme Symbolists, the world was insignificant and the spirit all; they were happy to mix and match spiritual doctrines for their own ends. That kind of individualism and subjectivity can easily lead to an emphasis on self-preservation at any cost, a willingness to reinvent one’s frame of reference to suit that end. In contrast, the Acmeists valued craft, the poem in itself, and they valued the phenomenal world. Mandelstam once defined Acmeism as “nostalgia for world culture.” Nadezhda says, it was “also an affirmation of life on earth and social concern.” In “The Morning of Acmeism,” Mandelstam says, “The earth is not an encumbrance or an unfortunate accident, but a God-given palace.” That implies attention and awe, and also a belief system that looks beyond the utilitarian. As to nostalgia for world culture, that implies an awareness of history, the classical world, a larger frame of reference and sensibility than his own moment. Along with this was his personal sense of identification with his fellow humans, among whom he lived and shared a fate, and his sense of not speaking for them, but with them.

Because Mandelstam valued craft, attended to the roots and origins of words, to tradition, nothing in his understanding of himself or poetry would allow him to write propaganda. Identifying with the people, with the earth, and a larger world perhaps reinforced his own innate sense of responsibility. As a Jew in Tsarist Russia, he was used to being on the edge of admission, which may have helped him remain clear eyed and skeptical of mass indoctrination.

Finally, there was his sense of poetry as a calling, not a profession. He once pushed a fellow poet down the stairs for complaining about not getting published, and shouted at him, “What Jesus Christ published?” He lived a literary life, writing essays while traveling by boxcar and crashing at various places. But he didn’t will poems into being. Either they came or they didn’t. When they came, they often began physically as a ringing in the ears before the formation of words, a process he described as “the recollection of something that has never before been said, and the search for lost words….” He didn’t sit at a desk. He paced, or walked through the streets, muttering, concentrating so hard, sometimes he’d get lost. He never wrote down the “Stalin Epigram.” Whoever turned him in remembered it well enough to recite it for the police to write down. If Mandelstam had been less overwhelmed by his interrogator, he’d have known from the version shown him, which reading his betrayer had attended. At any rate, such a view of art and such a mode of composition suggest that poetry was too essential to his very being to be transgressed. The one time he composed at a desk it was his “Ode to Stalin,” written in the hope of gaining his freedom, but written with such contradictions embedded in the language, it couldn’t possibly have worked. He simply couldn’t conceal his attitude toward tyranny, murder, blind obedience and self-interest.

I used to think Mandelstam was harassed for being a personal poet, for maintaining belief in the individual spirit, in independence and privacy, against the tyranny of the collective. You might see that in this poem, “Leningrad,” as translated by Merwin.

I’ve come back to my city. These are my own old tears,

my own little veins, the swollen glands of childhood.

So you’re back. Open wide. Swallow

the fish-oil from the river lamps of Leningrad.

Open your eyes. Do you know this December day,

the egg-yolk with the deadly tar beaten into it?

Petersburg! I don’t want to die yet!

You know my telephone numbers.

Petersburg! I’ve still got the addresses:

I can look up dead voices.

I live on back stairs, and the bell,

torn out nerves and all, jangles in my temples.

And I wait till morning for guests that I love,

and rattle the door in its chains.

Leningrad, née St. Petersburg, is where Mandelstam grew up. And where like Dante he was never able to live again. This was composed in 1930, during Mandelstam’s final unsuccessful attempt to settle in Leningrad. I love the way he evokes childhood in the first couplet, and then moves from the swollen glands to the second couplet, which seems to superimpose onto that childhood with its fish-oil tonic the darker experience. “Open wide. Swallow,” a mother or doctor might say to a child. But now he is swallowing the new city of Leningrad, no longer Petersburg, no longer the capital or the most Western city in Russia. Now he is swallowing the oily river. “Open your eyes” the speaker says to himself, and raises the question of “this December day,” the deadly tar in the egg—as if everything now is dangerous. December evokes the Petersburg worker strikes, which could be called the start of the revolution in 1904.

“Petersburg!” he cries out, addressing the old life. “Petersburg!”—the city where his friend and Akhmatova’s husband Nicolai Gumilev was executed, the city that evokes his desire to live and his fear of dying. Tapped wires, death threats, the old addresses of those who have been arrested or killed. Apartments split up so people live in just one room, or less. Internal and external disharmony—the bell’s torn wires, the frayed nerves. And the speaker waits all night for “the guests that I love,” some remaining fragment of humanity, perhaps. He rattles his own door, as if it’s been locked from outside—an image of the individual trying to break out of the imposed restriction.

But is this what Mandelstam wrote? Bernard Meares’ translation, apparently approved by Joseph Brodsky, ends with these two couplets:

I live on the backstairs and the doorbell buzz

Strikes me in the temple and tears at my flesh.

And all night long I await those dear guests of yours,

Rattling, like manacles, the chains on the doors.

“Dear guests,” according to Meares, is a euphemism for the political police. Tony Brinkley, who also translates Mandelstam, says that “gostei dorogikh (‘dear guests’) might also be translated as ‘special visitors.’ Dorogik apparently means ‘dear’ as in expensive, i.e. you pay dearly. Gostei can also mean ‘visitors’. In any case these guests, I think, are the Cheka, the GPU, the political police.” So in Meares’ version, it’s the speaker who has chained the door, though the need for those chains makes them feel like manacles, and also suggests a fear of future imprisonment. But the guests clearly are not loved ones; those “dear guests of yours” suggests the beloved city is now in collusion with the police, the old city of his childhood, the cultural capital, is gone, and the place now is associated with danger, betrayal, arrest

“Dear guests,” according to Meares, is a euphemism for the political police. Tony Brinkley, who also translates Mandelstam, says that “gostei dorogikh (‘dear guests’) might also be translated as ‘special visitors.’ Dorogik apparently means ‘dear’ as in expensive, i.e. you pay dearly. Gostei can also mean ‘visitors’. In any case these guests, I think, are the Cheka, the GPU, the political police.” So in Meares’ version, it’s the speaker who has chained the door, though the need for those chains makes them feel like manacles, and also suggests a fear of future imprisonment. But the guests clearly are not loved ones; those “dear guests of yours” suggests the beloved city is now in collusion with the police, the old city of his childhood, the cultural capital, is gone, and the place now is associated with danger, betrayal, arrest

Meares gives us a different poem, maybe even a different poet from Merwin’s, and a significant filling in of our understanding. Still, the Merwin to my mind is a better poem. Compare the first 3 couplets:

I’ve come back to my city. These are my own old tears,

my own little veins, the swollen glands of childhood.

So you’re back. Open wide. Swallow

the fish-oil from the river lamps of Leningrad.

Open your eyes. Do you know this December day,

the egg-yolk with the deadly tar beaten into it?

to Meares:

I returned to my city, familiar as tears,

As veins, as mumps from childhood years.

You’ve returned here, so swallow as quick as you can

The cod-liver oil of Leningrad’s riverside lamps.

Recognize when you can December’s brief day:

Egg yolk folded into its ominous tar.

The Meares has little of Merwin’s fluidity, Merwin’s music, swollen glands to swallow, the use of “Open wide” and “Swallow” to evoke childhood, which then shifts to the poet’s self injunction to be to open his own eyes, a move from the old nurture to the current need for vigilance. Merwin in general is more concrete and more colloquial.

But did Merwin read a softer, less political Mandelstam, one for whom nostalgia was stronger than anxiety, one less willing to define the nature of experience in Soviet Russia?

But did Merwin read a softer, less political Mandelstam, one for whom nostalgia was stronger than anxiety, one less willing to define the nature of experience in Soviet Russia?

The Meares translation in particular suggests that for Mandelstam the political and the personal were never separate, that he responded to the world around him with all of his interior resources. Here is a poem (Merwin translation) written during the last six months of his exile in Voronezh, # 355:

Now I’m in the spider-web of light.

The people with all the shadows of their hair

need light and the pale blue air

and bread, and snow from the peak of Elbrus.

And there’s no one I can ask about it.

Alone, where would I look?

These clear stones weeping themselves

come from no mountains of ours.

The people need poetry that will be their own secret

to keep them awake forever,

and bathe them in the bright-haired wave

of its breathing.

Richard and Elizabeth McKane say, “The people need a poem that is both mysterious and familiar.” I guess we can see this poem as a model—the spider web of light, the shadow of hair, juxtaposed with Mount Elbrus, the highest mountain in the Caucasus. There’s something mysterious in those images, at least to my mind. What does it mean to be in the “spider-web of light?” Is the poet caught, a fly entangled in the web? Yes. But it’s a web of light, and the people need light. So perhaps it’s not only an image of entrapment, but also one of being at the center of an act of making. There’s an old myth that has Prometheus shackled to Mt. Elbrus, so perhaps Mandelstam is imagining a new Prometheus who would meet his people’s needs, not stealing fire, but language from the gods of the state.

Richard and Elizabeth McKane say, “The people need a poem that is both mysterious and familiar.” I guess we can see this poem as a model—the spider web of light, the shadow of hair, juxtaposed with Mount Elbrus, the highest mountain in the Caucasus. There’s something mysterious in those images, at least to my mind. What does it mean to be in the “spider-web of light?” Is the poet caught, a fly entangled in the web? Yes. But it’s a web of light, and the people need light. So perhaps it’s not only an image of entrapment, but also one of being at the center of an act of making. There’s an old myth that has Prometheus shackled to Mt. Elbrus, so perhaps Mandelstam is imagining a new Prometheus who would meet his people’s needs, not stealing fire, but language from the gods of the state.

Then there’s the poet’s isolation. As the McKanes have it, “There’s no one to give me advice, and I don’t think I can work it out on my own.” Mandelstam is literally isolated, having set out on a course of resistance. Beyond that, questions of what the people need, what the poet can give, what the light exposes, are bigger than anyone can fully answer. There’s both vulnerability and resolve in these lines. The weeping stones—perhaps in snow melt, or a stream from that mountain—also combine something hard with something vulnerable, a lament perhaps for the distance the current age has moved from its cultural heights. The poem itself is a mix of strength and weakness, assertion and secrecy. Poetry becomes a means of awakening, but secret, as opposed to corrupted by public speech. Whatever translation we look to for the end, we see that quality of transformability that Mandelstam praises in Dante, as poetry in its cleansing power becomes water, wind, voice and breath. In the McKane’s translation the connection to earth is more prominent, but in either case there’s an immersion, poetry as a form of cleansing.

Late Mandelstam poems are very compressed, and often combine a sense of pleasure or beauty with a sense of doom. Here’s a short poem from March 1937, not too divergent in its translations, Merwin’s translation of “Winejug”:

Bad debtor to an endless thirst,

wise pander of wine and water,

the young goats jump up around you

and the fruits are swelling to music.

The flutes shrill, they rail and shriek

because the black and red all around you

tell of ruin to come

and no one there to change it.

In a museum in Voronezh Mandelstam had seen a Greek urn on which satyrs are playing flutes, and apparently angry at the chipped condition of the jug. But of course we can’t help reading as well the state of the country, and situation of the Mandelstams in particular. I think of Mandelstam visiting the museum in Voronezh, and no matter what pressure he is under—broke, spied upon, unable to get work, having to change apartments constantly—still he celebrates these artifacts of world culture—celebrates and mourns. In the same month he writes “The Last Supper”:

The heaven of the supper fell in love with the wall.

It filled it with cracks. It fills them with light.

It fell into the wall. It shines out there

in the form of thirteen heads.

And that’s my night sky, before me,

and I’m the child standing under it,

my back getting cold, an ache in my eyes,

and the wall-battering heaven battering me.

At every blow of the battering ram

stars without eyes rain down,

new wounds in the last supper,

the unfinished mist on the wall.

[Merwin’s translation]

We begin with a sort of allegory. The heaven of the supper fell in love with the wall. The intensity of heaven both cracks the weak vessel of the wall and fills it with light, which suggests an incarnation, the divine breaking into the human, and also perhaps something about how inspiration works. We’re looking at Da Vinci’s painting, of course, so this light manifests itself through the thirteen heads of the disciples and Christ—as if illumination needs concrete vessels. Thoughts of the painting move him to recognize another form of illumination, the night sky, before which he becomes a child—in memory and in the experience of awe. But if he feels the awe of a child, under the whole night sky, there is also a chill—the cold is at his back, the ache in his eyes. This heaven has something of violence in it—wall-battering and battering him. A more positive reading of this image suggests the way any spiritual or aesthetic experience breaks down walls, knocks us out of our habitual slumber, out of the familiar and into the strange ache of revelation.

But then the poem turns to a different kind of battering for sure: the battering ram, stars without eyes—headless stars, the McKanes say—whatever they are, they are no longer the disciples bearing a message of forgiveness and peace. New wounds in the last supper, suggest new betrayals, new deaths. Christ on the cross said, “It is finished,” but here nothing is finished, the battering goes on. I don’t know what that “mist” is about. The McKanes translate that as “the gloom of an unfinished eternity…,” so maybe it alludes to the mist and chaos at the beginning of creation. The painting Mandelstam would have seen in was severely damaged in the 17th and 18th centuries. In the last verse, according to the McKanes, the word “ram” in Russian is “tarana,” one vowel away from “tirana,” which means tyrant.

Here’s one more poem, this one from Mandelstam’s early days in Voronezh. It’s the second poem recorded in the notebooks he kept there. From Voronezh, April, 1935:

Manured, blackened, worked to a fine tilth, combed

like a stallion’s mane, stroked under the wide air,

all the loosened ridges cast up in a single choir,

the damp crumbs of my earth and my freedom!

In the first days of plowing it’s so black it looks blue.

Here the labor without tools begins.

A thousand mounds of rumor plowed open—I see

the limits of this have no limits.

Yet the earth’s a mistake, the back of an axe;

fall at her feet, she won’t notice.

She pricks up our ears with her rotting flute,

freezes them with the wood-winds of her morning.

How good the fat earth feels on the plowshare.

How still the steppe, turned up to April.

Salutations, black earth. Courage. Keep the eye wide.

Be the dark speech of silence laboring.

Merwin gives the suggestion of a horse more emphasis than other translators, who just say “well groomed,” or “everything groomed withers.” I’d like to think Merwin here is closer to the way Mandelstam works, with the same convertibility or transformability of Dante. There is an associative logic in going from manured earth, to that “fine tilth combed like a horse’s mane,” and then to let the horse move on pulling its plough, while the speaker remains looking at the turned-up earth like rows in a choir loft. Already a connection between earth and language is suggested, as well as earth and freedom, as if there is liberty in being grounded, in earth as a physical counter-weight to abstraction and deceit, the entire Bolshevik collective machinery. Merwin’s “labor without tools” suggests the earth’s own work of germination, separate from what its workers might will. While other translators speak of “unwarlike labor” or render the phrase as “ploughing is pacifist work,” Merwin’s “the labor without tools” hints more at Mandelstam’s way of composition—the labor of language beginning to emerge first without language. I don’t know what Russian word “rumor “ is translating, but it’s interesting that the Latin root of our “rumor” means “noise.” We tend to read it as pejorative, but it could also hint at something else, the incipient word coming from a distance (literal or psychic), not yet fully heard or realized. In “The Word and Culture” Mandelstam writes “Poetry is a plough, turning up time so that its deep layers, its black earth appear on top.” Clearly, earth and language are intimately connected here. And yet earth is a mistake. Is it a mistake to the Soviets who can’t control it they way they can control human beings? Or is it a mistake for us to expect consolation from the earth? No answered prayers, no protection in nature. But there is a kind of music that is mixed with its own demise, its own vulnerability. Earth pricks our ears with her rotting flute, or her mildewed flute, she sharpens our hearing with her dying flute. What moves, what quickens us in the natural world is its very temporal nature. Our ears are ploughed (in Greene) or frozen—big difference—with morning sounds: the wood-winds of morning, a chilly morning clarinet. The music is not permanent, but it sharpens or whets our hearing. How clearly Merwin goes for the more physical: “pricks up our ears,” which hints at the horse in those opening lines.

There’s a celebration in the final quatrain. The silence is fruitful, a germination.

Salutations, black earth. Courage. Keep the eye wide.

Be the dark speech of silence laboring.

I love Merwin’s continuation of the direct address, a kind of simpatico here, a little shared and benign conspiracy. The McKanes break that sense with, “There is a fertile black silence in work.” Greene: “A black-voiced silence is at work.” In any case, the silence is fruitful, there’s a germination going on, something stirring—perhaps Mandelstam’s hope that there in Voronezh language will come back to him, an unwarlike work. But the place isn’t without danger. He is still under surveillance. Even the earth needs courage, needs to keep the eye wide, and the speech that comes may be dark. Later, in fact, he will write a darker poem, which reduces the earth to the size of his grave:

You took away all the oceans and all the room.

You gave me my shoe-size in earth with bars around it.

Where did it get you? Nowhere.

You left me my lips, and they shape words, even in silence.

Mandelstam found other things left to him, even in exile. “You’re still alive,” he tells himself, and lists those great oxymorons: “Opulent poverty, regal indigence!” If we ask how a poet can survive under deprivation and oppression, perhaps the ability to live in contradictions, to accept paradox has something to do with it. Mandelstam uses the word “blessed,” and speaks of his work as innocent, “the labor’s singing sweetness,” or in the McKane, “the sweet-voiced work…without sin.” So, his own integrity is a comfort.

Perhaps no better example of that integrity comes from the translation work of Tony Brinkley and Raina Kostova. Here is their translation of the fourth section of “Lines on the Unknown Soldier,” complete with some Russian words left in the text to illustrate their point:

An Arabian medley, muddled, tangled, crumbling,

World-light of velocities, ground to a beam—

On my retina the beam pauses

In my eye on squinted feet.

Millions of dead men cheaply killed

Have walked a path through emptiness—

Good night! Best wishes to them all!

From the façade, the face of these earth-fortresses.

Sky of the trenches, incorruptible,

The sky of mass, of wholesale deaths,

Beyond, behind—away from you—entirely—

I am moving with my lips in darkness.

Beyond the craters, the voronki, behind embankments,

Scree, osypi—where he lingered, darkened,

Overturning—gloomy, pockmarked, ospennyi

The unsettled graves’ belittled genius.

In the final stanza the translators show us how carefully Mandelstam worked, nesting words within words, drawing on roots and origins, using echo and innuendo—much as Dante does, whom Mandelstam read in the original Italian. Brinkley and Kostova include some of the Russian words here, along with notes to explain the way meanings are embedded. They point out that voronki means “craters,” but also names Voronezh, and more than that it is also the name for the “ ‘little ravens,’ the black vans that roamed city streets at night and that the police used to transport prisoners.” Mandelstam’s name, Osip, appears in osypi (scree) and ospennyi (pockmarked), but those words also suggest Stalin’s pockmarked face and his given name, which is also Joseph or Osip. Just this brief excerpt shows us how carefully Mandelstam worked, his ear always to the language, hearing echoes, roots, reverberations. Language was something almost sacred, it seems, far beyond a tool for manipulation. The language becomes co-creator with the poet, suggesting a little more concretely what Mandelstam means when he describes his process as “the recollection of something that has never before been said, and the search for lost words…”—words lost within words, or buried there.

*

I was reluctant to write about Mandelstam for fear of a kind of desecration, my words dimming, rather than illuminating his work. I am equally reluctant to conclude, perhaps for a similar reason. One realization I’ve come to is that it would be an error to mistake intimacy with a translation for intimacy with the original. But I would actually like to celebrate that distance. When I first read Mandelstam’s “Conversation about Dante,” it was in winter. I was sitting in the window with the whole vast black night behind me, and on my lap? –an English translation of that twentieth century post-revolution Russian writer discussing his reading of a medieval poet in the original Italian. It seemed miraculous to be there, holding such vast distances in my hands. Perhaps the enormous gap in time, language, history, culture makes what we have all the more precious. Still, that gap is certainly real: between the text and what we can absorb, between Mandelstam and us, us and Dante, you and me. Maybe the sense of lifting one veil only to find another describes all reading, describes our human condition.

A final reflection for me has to do with how we translate from Mandelstam’s life into our own. Perhaps in any age artists face the possibility of corruption, involving self-preservation, careerism, lesser ambitions, attitudes of superiority to fellow citizens. Perhaps it’s always hard to see our own temptations. For me, across the distance of time and culture and extremity, Mandelstam becomes a model of integrity, a reminder of a larger world culture, perhaps now many world cultures; he challenges me to sharpen my craft, to both broaden my engagement with the world and be more interior—and not to assume there’s a divide between the two. However limited our own audiences might be, those who find us still need a poetry that is “both mysterious and familiar,” that will be a shared secret to keep us awake: because even one reader counts in a world where nobody is expendable, which is the world Mandelstam loved and died for.

—Betsy Sholl

WORKS CITED

Brinkley, Tony and Kostova, Raina, “ ‘The Road to Stalin’: Mandelstam’s Ode to Stalin and ‘Lines on the Unknown Soldier,’’ Shofar, Summer 2003, Vol 21, N0. 4.

Mandelatam, Nadezhda, Hope Against Hope: A Memoir, trans. Max Hayward (New York: The Modern Library,1999).

Mandelstam, Osip, The Selected Poems of Osip Mandelstam, trans. Clarence Brown and W. S. Merwin (New York: New York Review of Books, 2004).

Mandelstam, Osip. Selected Poems, trans. James Greene (London: Penguin, 2004).

Mandelstam, Osip, The Voronezh Notebooks, trans. Richard and Elizabeth McKane,(Newcastle Upon Tyne: Bloodaxe Books, Ltd., 1996).

Mandelstam, Osip. 50 Poems, trans. Bernard Meares (New York: Persea Books, 1977).

Mandelstam, Osip, Complete Critical Prose, trans. Jane Gary Harris and Constance Link (Dana Point, California: Ardis, 1997).

Mandelstam, Osip, The Noise of Time, trans. Clarence Brown (New York: Penguin Books, 1985).

—————————-

Betsy Sholl served as Poet Laureate of Maine from 2006 to 2011. She is the author of seven books of poetry, most recently Rough Cradle (Alice James Books), Late Psalm, Don’t Explain,and The Red Line. A new book is forthcoming from the University of Wisconsin Press. Her awards include the AWP Prize for Poetry, the Felix Pollak Prize, a National Endowment for the Arts Fellowship, and two Maine Individual Artists Grants. Recent poems have appeared in Ploughshares, Image, Field, Brilliant Corners, Best American Poetry, 2009, Best Spiritual Writing, 2012. She teaches at the University of Southern Maine and in the MFA Program of Vermont College of Fine Arts.

Robert Day‘

Robert Day‘