Here’s a lovely, sad Childhood essay by Eric Foley. It’s a meditation on presence and absence, the presence of his sister growing up in Toronto and her sudden death, at the age of 14. It’s a meditation on photography and the strange way photographs carry the mark of absence, of love and loss, even as they record (in snapshots, sometimes double-exposed or damaged) the apparent trivia of family life. What’s the difference between life and a photograph? And what is the meaning of those ghostly images of loved ones now gone? Eric Foley has been a finalist for the Random House Creative Writing Award, the Hart House Literary Contest, and winner of Geist Magazine and the White Wall Review’s postcard story contests. Eric currently attends Guelph University’s Creative Writing MFA program (last summer, he was a student of mine in Guelph’s mentorship program), where he is at work on his first novel, and a memoir about living in Morocco. His poetry and criticism can be found online at influencysalon.ca.

dg

/

In photography, exhibition value begins to displace cult value all along the line. But cult value does not give way without resistance. It retires into an ultimate retrenchment: the human countenance. The cult of remembrance of loved ones, absent or dead, offers a last refuse for the cult value of the picture. For the last time the aura emanates from the early photographs in the fleeting expression of a human face. This is what constitutes their melancholy, incomparable beauty. But as man withdraws from the photographic image, the exhibition value for the first time shows its superiority to the ritual value. To have pinpointed this new stage constitutes the incomparable significance of [the photographer Eugène] Atget, who, around 1900, took photographs of deserted Paris streets. It has quite justly been said of him that he photographed them like scenes of crime. The scene of a crime, too, is deserted; it is photographed for the purpose of establishing evidence. With Atget, photographs become standard evidence for historical occurrences, and acquire a hidden political significance. They demand a specific kind of approach; free-floating contemplation is not appropriate to them. They stir the viewer; he feels challenged by them in a new way. At the same time picture magazines begin to put up signposts for him, right ones or wrong ones, no matter. For the first time, captions have become obligatory. —Walter Benjamin

The above quotation is from Walter Benjamin’s famous essay “The Work of Art in the Age of Mechanical Reproduction.” By cult value, Benjamin is referring to the private, ceremonial, spiritual status of the art object, where what matters most is the object’s existence, rather than it being constantly on view. The photograph in the family album or the musty cardboard box in the attic, rather than the framed print on the (facebook) wall. Writing in the 1930’s, Benjamin saw photography and film as “the most serviceable exemplifications” of a new function of art where “absolute emphasis” was placed on the exhibition value of the work. I’m interested in the tension that exists between cult value and exhibition value in relation to photographs taken prior to the existence of the digital realm for essentially private family albums. What happens to these images when they are scanned and disseminated online, for all to see? Who today would allow a picture of themselves to be taken (or to remain undeleted on a camera), without imagining its appearance on Facebook?

As I came to try and make a narrative out of a series of the most resonant photographs from my childhood, perhaps it is no surprise that I kept returning Benjamin, who, in the end, inspired me to use this narrative not only to narrate but also to essay, to attempt to think about the nature of photographs and their use within a family. Here then are a series of the pictures that still obsess me, an album of images for which I “have not yet found the law,” with obligatory captions (right ones or wrong ones, no matter).

.

November 16, 1979

An image is not a permanent referent for those complexities of life which are revealed through it; its purpose is not to make us perceive meaning, but to create a special perception of the object – it creates a vision of the object instead of serving as a means of knowing it. – Victor Shklovsky, “Art as Technique”

By a chance double exposure, the first picture taken of me, less than one hour old in my mother’s arms, also contains the last picture taken of her before she became a mother. In the ghosted image snapped one day earlier, she sits with her hands on her lap, hands that push through time to rest on my newborn head. Of course, I’m also in her stomach in that fainter image, more than a week overdue.

.

.

Eleven Days Old

One of the—often unspoken—objections to photography: that it is impossible for the human countenance to be apprehended by a machine. This the sentiment of Delacroix in particular. – Benjamin, The Arcades Project

“Look at the camera!” my parents must have said, voices young, soft, and joyous. “Look at Daddy!” My mother’s robed arm propping me up. What am I looking at? It appears to be an otherworldly orb, a gaseous rupture in the surface of the image, but in fact, this rupture inserted itself along my line of vision several months after the shutter was clicked.

In the spring of 1980 my father went on a canoe trip in with his best friend Joe, bringing along his camera, which contained the undeveloped film from my first months of life. Stepping out of the canoe, my father dropped the bag with the camera into the lake. When the pictures were finally developed, they had this milky, bluish cast, as if light were peeling away the surface of the image. My mother was heartbroken.

.

‘.

Fall, 1980

Over the next several years, my mother would take thousands of pictures, like this one of my father and me in France:

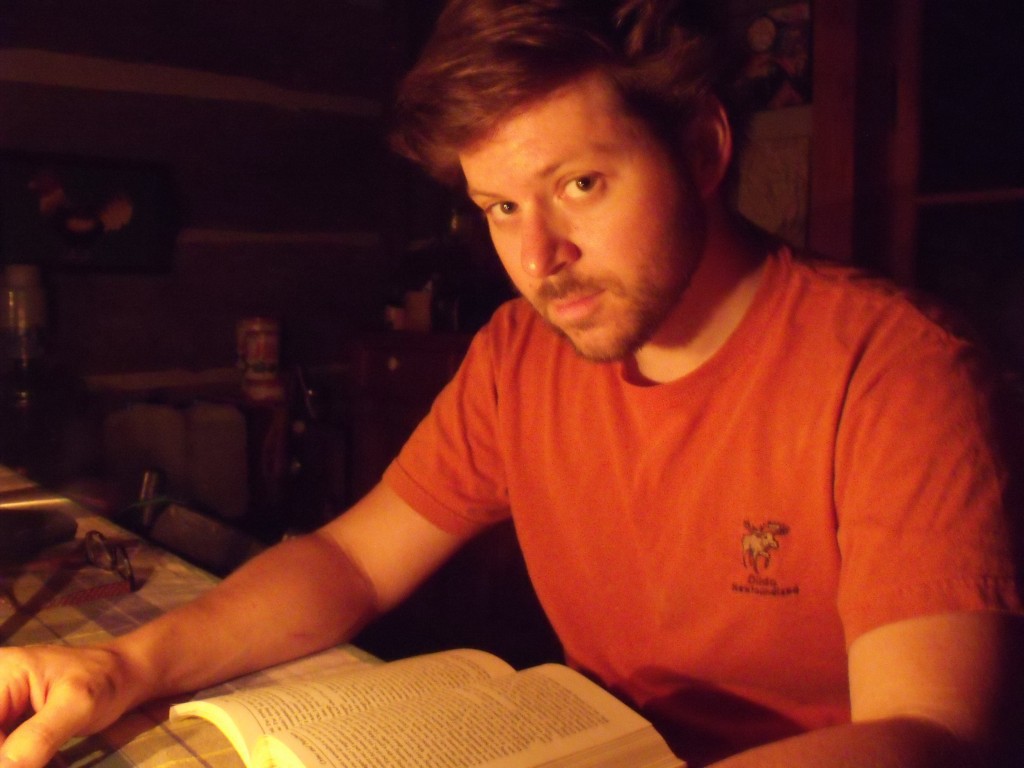

.Or the one that begins this piece, of my brother Andrew and me, which perfectly captures our opposing dispositions. Andrew: carefree, happy-go-lucky, singing away in his own fine world. Me: well, me.

.

103 Glenrose

Hopkins describes these obsessive images of objects as things for which he has not “found the law.” They are unfulfilled in meaning, but take up a lot of room in the memory as if in compensation. They seem both gratuitous and inexplicably necessary. – Charles Baxter.

I grew up in Toronto, in a three-story brick house surrounded by oak trees and lilac bushes. A beer commercial had been shot on the property a month before my parents bought it, and for the first few years we lived there, we would gather around the TV excitedly whenever the ad came on to watch three sweaty, blue-jeaned men kick back on our porch with a couple of cold ones.

I grew up in Toronto, in a three-story brick house surrounded by oak trees and lilac bushes. A beer commercial had been shot on the property a month before my parents bought it, and for the first few years we lived there, we would gather around the TV excitedly whenever the ad came on to watch three sweaty, blue-jeaned men kick back on our porch with a couple of cold ones.

Jumping through that first-floor window and reversing the camera angle, we can travel ahead seven years in time, to where I sit poised at our newly acquired 1906 Steinway Grand, my father’s dream-come-true..

“Put your hands out like you’re about to play,” my mother instructed, “and look over at me.” So I did. To take this picture, my mother would have had to stand in the entranceway to our living room, which, if we the reverse the angle again, is approximately here:.

“Put your hands out like you’re about to play,” my mother instructed, “and look over at me.” So I did. To take this picture, my mother would have had to stand in the entranceway to our living room, which, if we the reverse the angle again, is approximately here:.

.That piñata was one tough mother. Forty minutes of heavy abuse, and it wasn’t even dented. My friends and I exhausted, their parents due to arrive any moment, my father pulled the piñata down and dumped the candy onto the hardwood floor for us to flail over.

.That piñata was one tough mother. Forty minutes of heavy abuse, and it wasn’t even dented. My friends and I exhausted, their parents due to arrive any moment, my father pulled the piñata down and dumped the candy onto the hardwood floor for us to flail over.

.

Cottage

In making a portrait, it is not a question only…of reproducing, with a mathematical accuracy, the forms and proportions of the individual; it is necessary also, and above all, to grasp and represent, while justifying and embellishing,…the intentions of nature towards the individual. – Gisela Freund, “La Photographie au point de vue sociologique”

I had better luck with these two:

.

.

..

My mother snapped these from opposing angles in the living room of my grandparent’s cottage. The first was taken in the summer of 1987, at my sister Kristen’s third birthday party. The piñata hangs from a long wooden beam that at Christmastime held up to twenty-eight stockings at once. In the second image, you can see one of the stockings in my cousin John’s hands.

This picture was taken a few years earlier, from where the piñatas would later hang:

My parents had seen an ad in the paper for dwarf rabbits, and decided to get us one for Christmas. But by the time they went to pick one up, this monstrous creature was all that was left. It hopped around my grandmother’s carpet leaving a trail of brown pellets. Andrew crawled along behind picking up the pellets and putting them into his mouth, thinking they were chocolate-covered raisins. That spring, I forgot to close lid of the rabbit’s cage and the rabbit escaped. My Dad told us it probably got eaten by raccoons. The body was never found.

.

Speaking of Cages

Consideration of the image is still a sacred cause today only because the fate of thought and liberty are at stake in it. The visible world, the one that is given to us to see: is it liberty or enslavement? – Marie-Jose Mondzian, Image, Icon, Economy: The Byzantine Origins of the Contemporary Imaginary

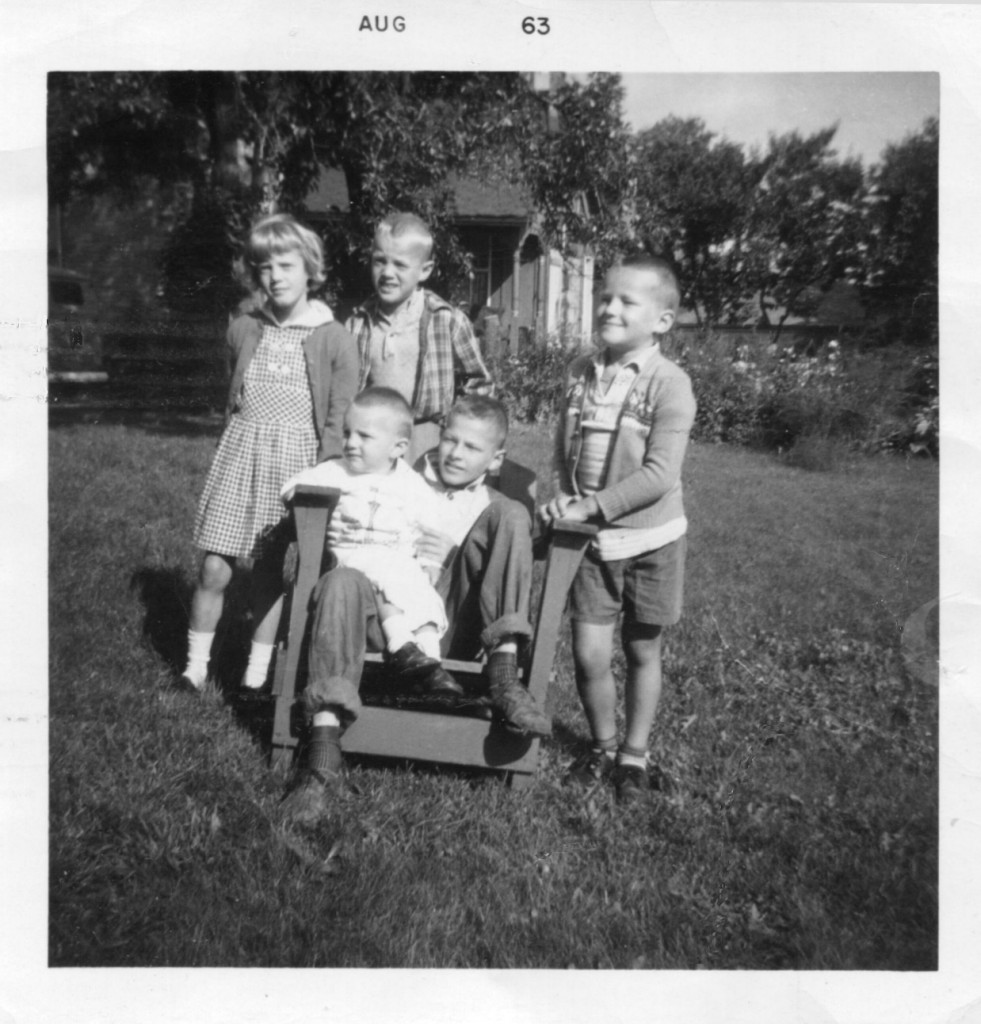

Two photographs taken thirty years apart. The first is of my mother on vacation with her family in Florida, 1961. The second one shows my sister Kristen with our new dog Tessa.

We used to go on a canoe trip every summer to Algonquin Park, and I always wished Tessa could come, but she was too hyper, my Dad said. He worried that if she spotted a loon she would go crazy, tip the canoe. I was, however, allowed to bring Tessa along in the form of an image of the two of us together on a t-shirt:

.

Rusty

Communications technology reduces the informational merits of painting. At the same time, a new reality unfolds, in the face of which no one can take responsibility for personal decisions. One appeals to the lens. – Benjamin, The Arcades Project

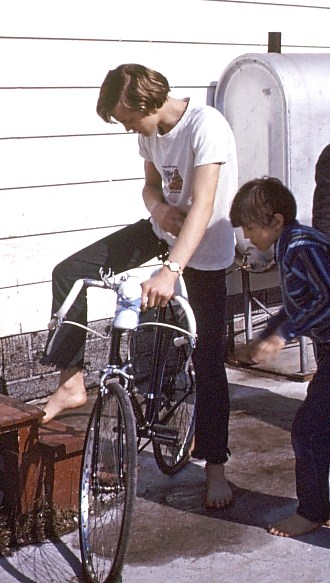

.

My brother’s favorite pet was a hamster named Rusty. Like our rabbit, Rusty also escaped. One day after school Andrew and I were playing floor hockey in our unfinished basement, when Andrew slapped the ball past me into the furnace room. I went in behind the woodpile to retrieve the ball and there was Rusty: trembling, emaciated. He had been missing for five days. Andrew carried him upstairs and tried to feed him, but the animal was too weak to ingest anything. When my father got home he gave Rusty a series of sugar-water infusions, reviving him for three weeks, after which the hamster passed away. “The shock to Rusty’s system must have been too great,” my father explained.

The above photograph was taken for a series of watercolor portraits my mother commissioned her friend Maureen to do (mine of course featured Tessa and me). In the background of the photo below, taken during one of our theme dinners, Andrew and Rusty’s portrait hangs above the mantle between a framed photograph of Kristen and one of me as a toddler standing beside a baguette. Here is evidence that not all the pictures my mother took were intended solely for our family albums (lined up chronologically in the cupboard behind my father’s left shoulder).

If, when she clicked the shutter, my mother happened to capture an image that made her feel a particular warmth within (and she says she always knew it with that initial click, before the film was developed), something to do with natural lighting, composition, the expression on a face she loved, if all of these combined to preserve a moment she wished to keep on seeing, then the image would be enlarged and placed on more permanent display..

.

No House, Hardly a Room

There used to be no house, hardly a room, in which someone had not once died. – Benjamin, “The Storyteller”

Going over these photographs, I think of the spaces they were taken in. What, besides pets, died there? A look? An object? A gesture? An idea?

These pictures were taken to preserve moments now past, but in another way they also constitute my past. As I grew, so did the pile of images that related to me, and I regularly went to that cupboard where the albums were kept and pored over them, using them to build the narrative of who I was, where and what I had come from.

I could always count on my mother to fill the plastic pages of those gilded, leatherbound books thick with photos from each year, forming a canon of accepted family imagery, a pictorial narrative that each of us could access at will (and, for the most part, agree upon).

Let it rescue from oblivion those tumbling ruins, those books, prints and manuscripts which time is devouring, precious things whose form is dissolving and which demand a place in the archives of our memory—it will be thanked and applauded. – Baudelaire, on the proper use of photography

.

Kristen

It is no accident that the portrait was the focal point of early photography. The cult of remembrance of loved ones, absent or dead, offers a last refuge for the cult value of the picture. – Benjamin, The Arcades Project

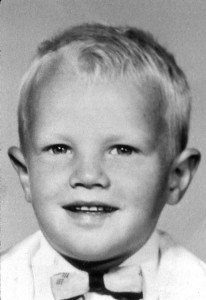

These pictures of my sister Kristen almost didn’t make it into the canon. They were taken after she had gone into the bathroom, aged three, and given herself a haircut. For years, Andrew and I used these images to tease her. She hated them, wanted them destroyed, at one point even stole them from the family album. I’m surprised they still exist. I’m glad they still exist, because in 1999, at the age of fourteen, Kristen died of meningitis, and our family’s narrative was irrevocably changed. After such an event, every trace of the past gains in significance.

Following Kristen’s death the old canon of images splintered apart, reforming with her at its centre, as my mother disassembled the master albums to make copies of pictures, reassembling them into more than fifty individualized mini-albums for friends and family.

For the last time the aura emanates from the early photographs in the fleeting expression of a human face. This is what constitutes their melancholy, incomparable beauty. – Benjamin, The Arcades Project

There are photographs from that time, still not held in any album, that are crucial to me. One shows my father kneeling in front of Kristen’s open casket, my two-and-a-half-year-old sister Kathryn in his arms in a green dress, sucking on the nub of a glass bottle filled with apple cider. Another is of the cemetery: it has started to rain, and I’ve just opened a burgundy umbrella, which I’m holding high over my mother’s head. My father and I are looking up at that umbrella as it floats above the crowd of relatives and friends. As I look at the picture now, it occurs to me that it is the only image I have of any of these people looking so sad; an uncomfortable thing to behold, but all the more valuable for that. Also: no one is looking into the camera. Their attention is elsewhere.

.

Postscript: Summer, 2002

In the end, we managed to convince our father to let us take Tessa along on a camping trip. She was nearly twelve by this point, her hips going, unlikely to bolt up for a bird or anything else. For the last three days of the trip my father had to carry Tessa, the hair of her hindquarters stained with diarrhea, along the portages. She died not long afterwards, but at least she got to see the Barron Canyon from the belly of a canoe.

The work of art is valuable only in so far as it is vibrated by the reflexes of the future. – André Breton

What reflexes vibrate these photographs? Are they art, or the merely the passing memories of a single family? The above image was taken on the first day of our trip to the Barron Canyon. Andrew and I, now young men, sit behind the stump of the jack pine from Tom Thomson’s iconic painting of Round Lake. The tree has been cut down years before, but a sapling grows from its roots. This picture takes me back to the very first in this series, of my brother and me as children. Many things happened between that earlier photo and this one. Many things happened afterwards, and continue to happen to each of us, every day, and we are all filled with multiple exposures. The hands of time push through to rest upon our heads. A feeling kicks in our stomachs, waiting to be born. But “the true picture of the past flits by,” as Benjamin says, and, at least for now, the images of all those places, times, and events not shared between us will have to remain lost.

—Eric Foley