Herewith a lovely, meditative essay on the conjunction of poetry, memory, and childhood from Nancy Eimers. The essay draws its inspiration from Proust and the art constructions of Joseph Cornell and draws to a close with Mary Ruefle’s Now-It, an erasure book made from an antique children’s book about Snow White. Nancy Eimers is an old friend and colleague at Vermont College of Fine Arts. In March NC published poems from her new collection, Oz, published in January from Carnegie Mellon University Press. Her three previous collections are A Grammar to Waking (Carnegie Mellon, 2006), No Moon (Purdue University Press, 1997) and Destroying Angel (Wesleyan University Press, 1991). She has been the recipient of a Nation “Discovery” Award, two National Endowment for the Arts Creative Writing Fellowships and a Whiting Writer’s Award, and her poems have appeared in numerous anthologies and literary magazines. Nancy teaches creative writing at Western Michigan University and at the Vermont College of Fine Arts, and she lives in Kalamazoo, Michigan.

dg

Charmed Objects: Poetry and Childhood

By Nancy Eimers

The genius of Cornell is that he sees and enables us to see with the eyes of childhood, before our vision got clouded by experience, when objects like a rubber ball or a pocket mirror seemed charged with meaning, and a marble rolling across a wooden floor could be as portentous as a passing comet. —John Ashbery

Image from Webmuseum at ibiblio

Image from Webmuseum at ibiblio

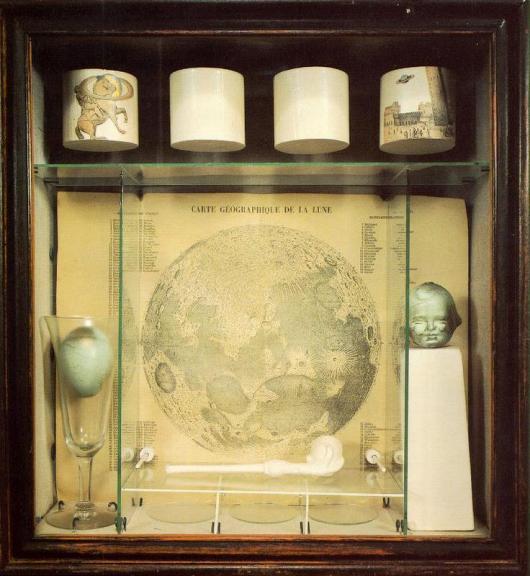

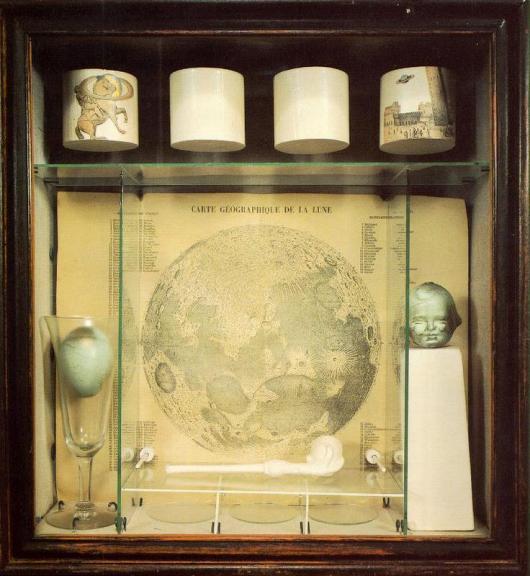

Joseph Cornell’s Untitled (Soap Bubble Set) is a brown box with metal handles on either side. Here is a list of its contents.

—blue cloth

—blue thumbtacks

—a map of the moon

—three glass discs

—light blue egg, in a cordial glass

—doll’s head, painted blue and gold

—three white wooden blocks

—white clay bubble pipe

Really, they are ordinary things, in one world or another.

If you visit Untitled (Soap Bubble Set) in the Wadsworth Atheneum Museum of Art in Hartford, Connecticut, you must keep a distance. You will not be allowed to open the box and play with the bubble pipe. Not even if you bring a child.

Now, a look at the box. But not an image. Words are the medium here.

Oh roundnesses you can feel in the palm of the hand. The moon’s at the center, silvery blue, and dominates. Carte Geographique de la Lune. The doll’s head, cheeks scarred, has been smiling now for how many years? Also a silvery blue, the doll and the egg are bathed in the thought of the moon. The discs of glass are laid at the floor of the box; if you picked one up, the rim might cut your hand. Every circle is synonym to a bubble: doll’s head, egg, bowl of the pipe. Even the craters of the moon. One of the books Cornell loved was a series of lectures delivered in 1890 by a scientist, C. V. Boys, to an audience of children, on soap bubbles. You cannot pour water from a jug or tea from a tea-pot; you cannot even do anything with a liquid of any kind, without setting in action the forces to which I am about to direct your attention.

Image from Rocaille

Image from Rocaille

I haven’t seen that soap-bubble box except in a book, but I’ve seen Untitled (Forgotten Game) in Chicago’s Art Institute. A pinball-like game of a box with holes behind which there are pictures of birds cut out from the pages of old books. Inside the box there are ramps down which a ball is meant to slide. If you could open the little door at the top and insert a blue rubber ball, if the ball were to slide down the ramps and reached the bottom, a bell would ring. That it doesn’t ring is part of a terrible sweetness.

Forgotten game, blue-silver moon, recessed birds, egg in a cordial glass, to what forces have you drawn our attention?

“Perhaps what one wants to say,” said sculptor Barbara Hepworth, “is formed in childhood and the rest of one’s life is spent in trying to say it?”

*

I remember a gaudy, jeweled pin worn by my grandmother. I say “gaudy,” but I didn’t think it was gaudy then. Costume jewelry is made of less valuable materials including base metals, glass, plastic, and synthetic stones, in place of more valuable materials such as precious metals and gems, explains Wikipedia helpfully. But I hadn’t read and wouldn’t have been helped by this sentence then. The jewels, their blue and pink sparkles, enchanted me. They seemed almost to say, there is this other world. The pin is lost forever, like Dorothy’s ruby slippers somewhere between Oz and Kansas. But I feel the pull of a former feeling, not subject to reason, proportion, knowledge of anything likely/unlikely to happen. In memory, where I am holding it in my hand, the invented and the real haven’t quite parted ways. You can’t get beauty. Still, says Jean Valentine, in its longing it flies to you.

I think this will not be an argument but a meditation—held together by asterisks, little stars—on how charmed objects, long lost, come back sometimes in poetry, present only as words, touchstone, rabbit’s foot, amulet, merrythought, calling us back, calling us forth. What are they, now that we’ve lost them?

*

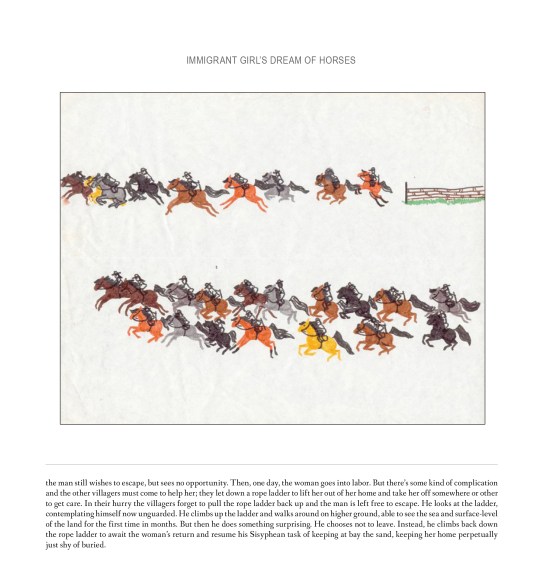

The Child Is Reading the Almanac

The child is reading the almanac beside her basket of eggs.

And, aside from the Saints’ days and the weather forecasts,

she contemplates the beautiful heavenly signs.

Goat, Bull, Ram, Fish, etcetera.

Thus, she is able to believe, this little peasant child,

that above her, in the constellations,

there are markets with donkeys,

bulls, rams, goats, fish.

Doubtless she is reading of the market of Heaven.

And, when she turns the page to the sign of the Scales,

she says to herself that in Heaven, as in the grocery store,

they weigh coffee, salt and consciences.

In an almanac there are moons, full and half and quarter, and there are new moons that look like black moons. There are meteor showers, tides and eclipses. Signs of the zodiac. Questions of the Day. Why is the ring finger sometimes called the medical finger? Weather predictions. Three misty mornings indicate rain. Fact and prediction, the seen and the unseen intermingle; the strange is detected in the commonplace, and the commonplace in strangeness. No wonder the child in this early twentieth century poem by French poet Francis Jammes has been tempted to set down her basket and read.

Jammes “wrote of simple, everyday things,” says the introductory paragraph on the torn yellow book jacket of my copy of his Selected Poems. And inside the book, in the introduction, Rene Vallery-Radot marvels, “From a little provincial town there rises a voice that ignores all the gods, that tells of life simply, not at all systematized in theories.” In a photograph just inside the cover Jammes, an old man in round black glasses and a long wispy beard, looks down at a page he is writing on. For all we know he was writing this almanac poem. The child must have stopped on her way to or from the market (to sell the eggs? having just bought them?). Perhaps she wonders if even an egg, like the animals in the market, has its counterpart in the stars. The wondrous almanac testifies that as things are on earth, so they must be in heaven: how miraculous, how natural, that Heaven resembles an earthly grocery store on this most ordinary of days!

Still, Jammes remembers enough not to oversimplify, or presume. On earth, scales are also associated metaphorically with justice, even by a child. And like any child, this one must have done something, committed or contemplated committing some small act, a rebellion or peccadillo for which, in some small way, she’d paid, or feared to pay. She spoke harshly to the donkey. Maybe she broke an egg. She dawdled on the way to the market. Whatever it is, she keeps it secret. Let us not trespass.

*

It is because I believed in things and in people while I walked along those paths that the things and the people they made known to me are the only ones that I still take seriously and that still bring me joy. Whether it is because the faith which creates has ceased to exist in me, or because reality takes shape in the memory alone, the flowers that people show me nowadays for the first time never seem to me to be true flower. —Marcel Proust, Remembrance of Things Past

In her autobiographical story “In the Village,” Elizabeth Bishop invents or remembers this from her childhood:

We pass Mrs. Peppard’s house. We pass Mrs. McNeil’s house. We pass Mrs. Geddes’s house. We pass Hill’s store.

The store is high, and a faded gray-blue, with tall windows, built on a long, high stoop of gray-blue cement with an iron hitching railing along it. Today, in one window there are big cardboard easels, shaped like houses—complete houses and houses with the roofs lifted off to show glimpses of the rooms inside, all in different colors—with cans of paint in pyramids in the middle. But they are an old story. In the other window is something new: shoes, single shoes, summer shoes, each sitting on top of its own box with its mate beneath it, inside, in the dark.

The child is bereaved, though she doesn’t entirely know what this means. It is for her too new a story. Her father—her mother’s mate—like one of those shoes, has been closed inside a box of his own, but forever, unlike the shoes. This story is one of those houses with its roof lifted off, so the writer, so we, may look inside. But we may not enter.

Memory affords glimpses: of a flower, a doll or a shoe in a box, a marble rolling comet-like across the floor. “My life,” writes Tomas Transtromer:

Thinking these words, I see before me a streak of light. On closer inspection it has the form of a comet, with head and tail. The brightest end, the head, is childhood and growing up. The nucleus, the densest part, is infancy, that first period, in which the most important features of our life are determined. I try to remember, I try to penetrate there. But it is difficult to move in these concentrated regions, it is dangerous, it feels as if I am coming close to death itself.

Maybe it is important not to explicate our childhoods. Or simply, merely impossible? Cornell, from a journal entry, May 13, 1944:

. . . stopped by pond of waterworks with cool sequestered landscaping—gardens & here had one of profoundest experiences + renewal of spirit associated with childhood evoked by surroundings—it seemed to go deep through this strong sense of persistence in the lush new long grass—the most prominent feature turned out to be “no trespassing” sign

Water, hiddenness, the cool, such things return for a moment from—exactly when and where? What did it look like there? We can’t quite know, we can’t see inside. No trespassing. But the grass is/was lush.

Talking about her younger brother Joseph, Betty Cornell Benton recalls this scrap from their childhood:

Late one night he woke me, shivering awfully, and asked to sit on my bed. He was in the grips of a panic from the sense of infinitude and the vastness of space as he was becoming aware of it from studying astronomy.

From an earthly point of view, a comet is stationary, seen at night—then remembered in daylight—then seen—then remembered—over the rooftops. It is there for a time. Star with a wake of light. Then it is gone. That too is remembered.

*

“Stove” is one of the six end-words of Elizabeth Bishop’s “Sestina.” A Little Marvel. Brand new, that model would have been painted silver. Through daily use, it would have grayed; open the door and it would be blackened inside. MARVEL: the name is on the door. It dominates like the map of the moon in Cornell’s soap bubble box. Above, below, on either side there are swirls and curlicues forged in the cast-iron, resembling serious, stirred up clouds. It has four legs, curving outward, stubby and braced. In an early twentieth century village, a stove was a daily thing in anyone’s house, but to a child it must have seemed marvelous, like Saturn’s rings.

I have only seen photographs of the Marvel; but they were not photographs of the real thing. All I found was a salesman’s sample, 16 inches high, still advertised on eBay but already sold. That ship had sailed. And a toy Little Marvel, complete with two ovens, burners and lifters. Nickel plating over cast iron. All complete and in very good all original condition.

A child in me is entranced.

September rain falls on the house.

In the failing light, the old grandmother

sits in the kitchen with the child

beside the Little Marvel Stove,

reading the jokes from the almanac,

laughing and talking to hide her tears.

House. Grandmother. Child. Stove. Almanac. Tears. Six end-words, like miniatures on a bracelet. (Even the tears have their charm.) Each time the words, all nouns, come back, they are in their original form—no juggling with word play or parts of speech, no punning or homonyms. Simple words, like primary colors, or figures from an old storybook.

Or they are like comets, passing before us seven times from the early twentieth century, Great Village, Nova Scotia. As in the story “In the Village,” there is death at the nucleus.

tears/house/almanac/grandmother/stove/child

child/tears/stove/house/grandmother/almanac

And so on. In the ordinary world a grandmother is trying to amuse a child. Each time a word comes around again it feels sadder. Even tears get sadder; the teakettle weeps, the teacup fills with dark brown tears. To the grandmother, tears are recurring, equinoctial. The child senses something. Unspoken grief is working its magic: the almanac begins to resemble a bird; the stove gets philosophical; the world grows cold. The almanac knows what it knows but won’t say what. How much does the child know, what is she warding off? The poet senses something. Does the child miss the man in the drawing? How much can even Bishop have known of the child she was? “Early Sorrow” was the poem’s original title. Then withdrawn. Explication fails, or it is irrelevant. The child sees little moons in the almanac fall down like tears. The poem ends, as it began, in present tense. The child draws another inscrutable house.

That moment of wonder and puzzlement goes on orbiting but it is in the past, forever out of reach. So are the stove and the almanac, ancient tears, the worried grandmother and the inscrutable child. All in the past, except for the house in Great Village. (. . . it is difficult to move in these concentrated regions, it is dangerous, it feels as if I am coming close to death itself.) That house is still there. You can visit it; you can go inside; you can even arrange to stay.

*

In her art review of the Ann Arbor exhibition “Secret Spaces of Childhood,” Margaret Price describes certain characteristics of childhood hide-outs:

Almost always the entrance to a secret space is guarded, to protect the privacy and sometimes the fragility of what lies inside. . . . Moving through the doorway into the space itself is often a rite of passage, and often the point of access is the most highly charged area of the whole secret space: usually elusive, always exciting, and sometimes dangerous. Often they, or their entrances, are small . . . . being small of stature confers the privilege of access. A hideout cannot function for a person too large to fit into it. On the other hand, a child’s small size is a passing attribute, and children know it.

Peering into the windows of a dollhouse, I feel almost an ache of pleasure. I think this has to do with its smallness; the feeling is paradoxical. I am charmed by the inaccessibility; and I yearn to be small enough to step inside. If I could grow small enough to enter, the house and furniture would no longer seem miniaturized to mini-me and so would have lost their mystery; but I might find among the toys in its nursery (for in a dollhouse there is almost always a nursery) a tiny dollhouse, and who knows, perhaps an even tinier dollhouse inside of that dollhouse’s nursery, and so on and so on, as if longing were satisfyingly infinite.

Is remoteness integral to a certain kind of charm? In a silk-lined box I keep my charm bracelet, a mercury-head dime and a single clip-on pearl earring. I know they are there, but I hardly ever look. I like the look of the hinge that fastens the lid.

from the Art Institute of Chicago

from the Art Institute of Chicago

On the basement floor of the Art Institute in Chicago you can visit the Thorne Rooms, a permanent exhibit of miniature rooms behind glass. These aren’t so much dollhouses as interiors, 68 rooms that, “painstakingly constructed,” as the museum website explains, “enable one to glimpse elements of European interiors from the late 13th century to the 1930’s and American furnishings from the 17th century to the 1930’s.” The rooms contain exact reproductions of period furniture, carpets, wallpaper, chandeliers, other objects—all somehow failing to interest me, I finally realized with some disappointment the last time I visited. Perhaps it was more petulance I felt than disappointment; I had come in the spirit of a former child, and being there felt more like studying than play.

What bewitched me, though, were the windows. Out every window there was a view—an exterior—tiny, intricate gardens with bushes and flowers; patios; benches; trees; and an artificial light from a source that wasn’t visible. I started over, room by room, looking not at interiors but out the windows, craning my neck to see as much as I could; it was tantalizing, I couldn’t see everything. Shining faintly into miniature rooms in the basement of a grand museum, the light seemed remote, a late-fall, old-world light. Out of every window of every one of the 68 rooms was a little world a child might just have begun imagining . . . .

Or perhaps it was simpler, perhaps I just wanted to be inside looking out. In fact, it occurs to me that may be why (at least in part) I’m so happy when it snows: as opposed to looking into dollhouses or the windows of other people’s lighted homes at night, I finally feel as if I’m inside something.

*

A charm is a miniature object worn on a bracelet. A sombrero. A bell. I am childless, who will I give it to? You can’t hear the tinkling of the tiny bell for the tinkling of the bracelet when you pick it up. The use of the word charm as trinket did not occur (was not recorded) until 1865. But charm has meant “pleasing” since the 1590’s.

It wasn’t until Elizabeth Bishop arrived in Brazil and found herself, for a time, enormously happy, that she began to be able to write of her childhood in Great Village. She says in a letter to friends, “It is funny to come to Brazil to experience total recall about Nova Scotia—geography must be more mysterious than we realize, even.”

Of course she meant some geography of the interior.

Even from the simplest, the most realistic point of view, the countries which we long for occupy, at any given moment, a far larger place in our actual life than the country in which we happen to be. —Marcel Proust

*

Ghost stories written as algebraic equations. Little Emily at the

blackboard is very frightened. The X’s look like a graveyard at night. The

teacher wants her to poke among them with a piece of chalk. All the children

hold their breath. The white chalk squeaks once among the plus and minus

signs, and then it’s quiet again.

This is an untitled prose poem from Charles Simic’s The World Doesn’t End. I have been that child, puzzling over the signs and portents on the blackboard, messages sent by way of math, of grammar, or even handwriting, strange row of continuous l‘s or o‘s. In a way, it seems like a minute ago. Did the teachers know how wildly some of us may been mistranslating what they were writing on the board? Numbers especially, and their plusses and minuses, went beyond the explanations of words, beyond even paragraphs. I am a teacher myself now, though white boards and dry erase markers have replaced the powdery chalk. I am still a little frightened, like Emily, standing in front of the class. The white boards haven’t solved or eliminated the mystery, yesterday’s propositions, assertions, and mistakes still lurking under today’s.

Though the blackboards of my childhood were almost always green, the first blackboards were black, made of slate. For a newer generation of blackboards, the color green was chosen because it was believed it would be easier on the eyes. As for the chalk, I can still feel the powder on my hands as I lay it back in one of the crevices of the metal rim. I had been asked to do a problem on the board. Or to outline a sentence. Or maybe I hadn’t touched it at all but was sitting at my desk, watching my teacher, mentally tracing the swoops of her hand (his hand) as it held the chalk. Oh mysteries of the chalkboard’s palimpsest, yesterday’s sums or sentences only half-erased. And let us not forget the mystery of the chalk itself, composed partly of limestone, the sum of fossilized sea animals.

*

Vivien Greene, whose family moved repeatedly when she was a child, devoted much of her adult life to the study, collection, and restoration of Victorian dollhouses. She had seen her own beloved house in London bombed and split open in the Blitz. It seems that rift was decisive: after that she and her husband (the novelist Graham Greene) permanently lived apart. (Graham, who wasn’t interested, said Vivien, in either her dollhouses or domesticity, had already formed what they used to call “another establishment.”) “Houses have influenced my life deeply,” wrote Vivien Greene in a brief essay called “The Love of Houses”; “They have entered into dreams, made me stand enraptured, suddenly in unexpected places, filled me with a longing to possess; or they occasionally frighten.” Fear of . . . bombs? Of ghosts, of moving yet again? She doesn’t explain. In the evenings during the war, she used to sit behind blackout curtains working on her dollhouses, tearing down old wallpaper, adding the new. Greene was the author of several excellent books on vintage English dollhouses. They are filled with exquisitely old-fashioned and discursive descriptions of staircases, windows, doorways, furniture, even the crockery. At one point, she writes, apropos of nothing,

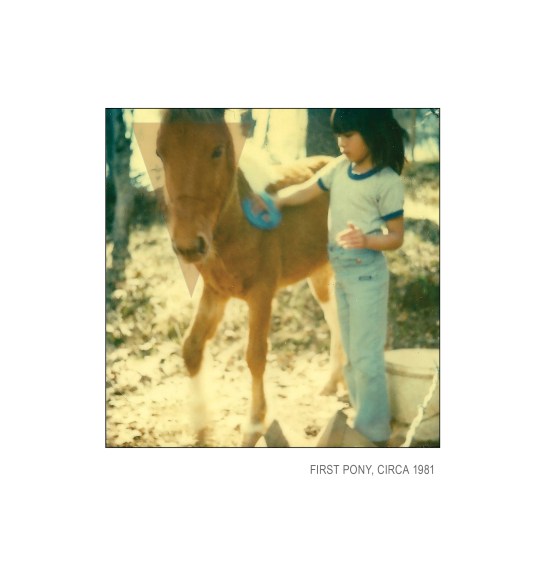

As some people ask and need to be stripped of ownership, so we can believe others are hardly fully alive, complete as persons, until certain material things, a horse, a place, a boat, have been loved and owned and afterwards remembered.

*

“In the lyric you can stop time,” said Ellen Bryant Voigt in an interview; “you pick that moment of intensity and hold it. The narrative moves through time.” In Michael Burkard’s poem “The Sea” nothing really happens. There is instead a kind of lyrical parallelism that advances no narrative but deepens the shades of emotion.

It could have been worse but for the sea. The watch of it. What was it

Chekhov wrote?—”Self same sea”—Yes. Yes. It was there, as was my mother’s

family, in Nova Scotia. There beyond the sloping meadow near Aunt Dorothy’s

farm, there from Cousin George’s kitchen window. The sea and its often daily fog

permeated everyone, everything. And because there was no electricity in those

days, only candles, lantern light, and no plumbing, it seemed almost a sea more in

the air than in the sea. You could not shut it out.

The poem travels sideways, or inward. Certain words appearing numerous times, sea, there, now, as if, become on one level sheer sound, a force, a mystery. They don’t so much stop the moment as return to its vivid pastness, over and over again. There is something bygone and sepia about the scene described. “There” suggests something in existence but away. The landmarks in the poem are family names, a meadow, a kitchen window. And the sea. Which is also a kind of weather, an intrusive force or guest. The residents of the poem are mired there, in a world miniaturized by memory. Here is the rest of the poem:

And the lanterns we ate by, sat by—how small! Yet this permeated as much as

the sea, as much as the fog from the field, the conversion of one cowbell to

another cowbell in the fog, the red-yellow light flickering, now against a deck of

cards, now against faces and hands playing the cards, now being carried with one

or by one off to sleep. Sleep by the sea, as if the sleep were to last a thousand

years, as if the summer were a medium for color which could become

permanently framed, wearing only so slowly for another thousand years. Self

same lantern light shadows, sea and shadow of sea, and her face there, a thousand

years ago, only to be seen a thousand years hence and then to stay beside her face

for as long as ever is.

The fog doesn’t so much occur as seem always to have been; the family members play cards, listen to sounds, fall asleep. Memory’s village: perhaps everything wasn’t always filmed over with sadness? “A thousand years” means one thing to a child looking forward, and something else to an adult looking back. Is the face that appears the face of the speaker’s mother? On one side is there and ago, on the other hence and ever. Stay is not an accomplishment but a plea. Ever: at all times; always. Matched by is, the moment stopped in time. He doesn’t say “forever,” though. He is, we are, outside the time that is “as long as ever”; it is already over.

Cowbells, by the way, come in various colors and sizes, but the ones I hear in the poem sound silver, and tarnished.

*

We move through time, like characters in a story. The objects we loved with intensity seem timeless. Is this because we let them go? And yet, resurrecting the thought of them, don’t loss and accomplishment co-exist? The story goes on and we go with it, but part of the story is what we’ve lost. In “Elegy for the Departure of Pen Ink and Lamp,” Zbigniew Herbert asks forgiveness from three charmed objects:

Truly my betrayal is great and hard to forgive

for I do not remember either the day or the hour

when I abandoned you friends of my childhood . . . .

His “friends” are: a pen with a silver nib, illustrious Mr. Ink, and a blessed lamp:

when I speak of you

I would like it to be

as if I were hanging an ex-voto

on a shattered altar

Herbert’s elegy might as easily be to a soap-bubble, or a forgotten game. But not to the story that edited them out.

I thought then

that before the deluge it was necessary

to save

one

thing

small

warm faithful

so it continues further

with ourselves inside it as in a shell

There is that moment when we touch something for the last time. But the child can’t know, as Herbert says, still addressing his “friends,” that “you were leaving forever / / and that it will be dark.” Against that dark, the poem saves one thing, something that, reimagined, paradoxically remains miniaturized but it holds us: it is we who dwell within.

But before we leave that dark, W. G. Sebald has something else to say about it:

. . . in the summer evenings during my childhood when I had watched from the valley as swallows circled in the last light, still in great numbers in those days, I would imagine that the world was held together by the courses they flew through the air. . . .

Some yearning of the child’s imagination, Sebald suggests, forged those patterns of meaning in the flights of swallows. If, like the swallows that have diminished in number, some freshness in our early imaginings gets lost along the way, poetry yearns for the “half-created” in things we once perceived. A Marvel stove, school chalk, cowbells, a blessed lamp, a silver nib, things that once ordered the dark—or were ordered by it. If nothing can bring back the hour of splendour in the grass, still, isn’t there something swallow-like and mysterious in our yearning, resistant yet integral to the very passage of time? Poetry imagines the traceries that might once again hold things together, lost possessions, past and present, worlds real and imagined. It restores the lost moment, shoe, cowbell, basket of eggs or blessed lamp, utterly itself; it is we who are changed, because we know it is lost.

* (last little star)

In Now-It, a collage-and-erasure book Mary Ruefle made out of an old children’s book called Snow White or the House in the Wood, she has pasted the words “the cry of the button” beside the picture of a streaking comet. Oh you here and there, you cry and streak, all that’s precious in the commonplace! Now that button and comet have found each other, the child in me believes nothing more need be said.

—Nancy Eimers

———————————————

Works Cited

Art Institute of Chicago, website on Thorne Rooms.

Ashbery, John. “Joseph Cornell,” Art News, summer 1967.

Bishop, Elizabeth. “In the Village,” in The Collected Prose. New York: Farrar Straus Giroux, 1984. 261-2.

Bishop, Elizabeth. “Sestina,” The Complete Poems. New York, Farrar Straus Giroux: 1983. 123.

Boys, C.V. Soap-Bubbles and the Forces Which Mould Them. Memphis: General Books, 2010 (reprinted).

Burkard, Michael, “The Sea,” My Secret Boat. New York: Norton, 1990. 22.

Cornell, Betty Benton, quoted in A Joseph Cornell Album, Dore Ashton, author. New York: De Capo Press, 1944.

Cornell, Joseph. Theater of the Mind: Selected Diaries, Letters and Files. Ed. Mary

Ann Caws. : New York: Thames & Hudson, 1993. 105.

Greene, Vivien. English Dolls’ Houses of the Eighteenth and Nineteenth Centuries. New York: Charles Scribner’s Sons, 1979. 23.

Greene, Vivien. “The Love of Houses,” The Independent (London), Nov. 29, 1998.

Hepworth, Barbara. From notebooks. Quoted in Barbara Hepworth Museum and Sculpture Museum, St. Ives.

Herbert, Zbigniew, “Elegy for the Departure of Pen Ink and Lamp,” Elegy for the Departure. Trans. John and Bogdana Carpenter. Hopewell, NJ: Ecco, 1999. 127-132.

Jammes, Francis. “A Child is Reading the Almanac,” Selected Poems of Francis Jammes. Trans. Barry Gifford and Bettina Dickie. Logan, UT: Utah State UP, 1976. 23.

Price, Margaret. “Secret Spaces of Childhood: An Exhibition of Remembered Hide-Outs,” Michigan Quarterly Review, Spring 2000. 248-278.

Proust, Marcel. Remembrance of Things Past: 1. Trans. C. K. Scott Moncrieff and Terence Kilmartin. New York: Penguin, 1954.

Ruefle, Mary. Now-It. Carol Haenicke Women’s Poetry Collection, Rare Book Room, Western Michigan University.

Sebald, W. G. The Rings of Saturn. Trans. Michael Hulce. New York: New Directions, 1999. 67.

Simic, Charles. “Ghost stories written,” The World Doesn’t End. Boston: Mariner Books, 1989. 13.

Transtromer, Tomas. For the Living and the Dead: New Poems and a Memoir. Hopewell, NJ: Ecco, 1995. 25.

Valentine, Jean. “Then Abraham,” Break the Glass. Port Townsend: Copper Canyon, 2010. 16.

Vallery-Radot, Rene. Quoted in Introduction,” Selected Poems of Francis Jammes. Logan, UT: Utah State UP, 1976.

Voigt, Ellen Bryant. Inteview, The Atlantic Online, Nov. 24, 1999.

It’s always been a dog backyard. Before Nixon we had Chevis and Bianca and Goth, but they all were old and soon would need replacing. Nixon was unlike any of those dogs, however. Where they were calm in their old age (the only ages at which I knew them), Nixon continued to act like a puppy long after he no longer looked like one. And I disliked him for this. His tail hurt when it wagged against your leg and it was always wagging. He bounded through the house if we didn’t confine him to the kitchen and, later, he became a chronic fence jumper. I suppose he had neighborhood gallivanting in his blood—after all, that is how he came to be. And even though I wanted to leave the backyard, to go beyond the fence, I couldn’t understand his need to do so. What did Nixon do out there among the wanderers? Did he mingle with the transients who asked for bus money? Did he run with the children on their way home from school? My parents warned if he did it again after so many times, they would not pick him up from the pound. I envisioned doggy gas chambers and wished he would just stay in the yard.

It’s always been a dog backyard. Before Nixon we had Chevis and Bianca and Goth, but they all were old and soon would need replacing. Nixon was unlike any of those dogs, however. Where they were calm in their old age (the only ages at which I knew them), Nixon continued to act like a puppy long after he no longer looked like one. And I disliked him for this. His tail hurt when it wagged against your leg and it was always wagging. He bounded through the house if we didn’t confine him to the kitchen and, later, he became a chronic fence jumper. I suppose he had neighborhood gallivanting in his blood—after all, that is how he came to be. And even though I wanted to leave the backyard, to go beyond the fence, I couldn’t understand his need to do so. What did Nixon do out there among the wanderers? Did he mingle with the transients who asked for bus money? Did he run with the children on their way home from school? My parents warned if he did it again after so many times, they would not pick him up from the pound. I envisioned doggy gas chambers and wished he would just stay in the yard.