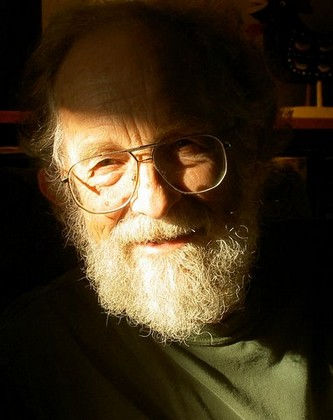

This is a stellar first for Numéro Cinq, a full-length original novella by Toronto writer Mike Barnes. The novella’s heterodox (and liberating) structure includes footnotes and photographs. Mike Barnes is the author of stories, novels, poems and a gorgeous memoir about his own descent into madness and recovery. This novella, too, deals with madness. It is an intricately structured rendering of madness and memory, a mix of hallucination and dense, concrete realism, which only makes the phantasmagoria of illusion all the more poignant. This is an amazing work—supremely intelligent, coolly self-analytical, eerie, melancholy, revelatory and terrifying.

dg

/

/

Food in dreams appears to be the same as food when awake, but the sleepers are asleep, and receive no nourishment.

—St. Augustine, Confessions Book III

On a spring afternoon in 2007, I was lying on the couch in my living room reading Simon Schama’s Power of Art. This chapter was an essay on Picasso’s Guernica. As I read Schama’s account of the German planes appearing in the sky over the Spanish town on April 26 1937, something caused me to look up from the book. The objects of the living room, clearly outlined in the spring light, seemed altered somehow, stark yet dubious along their edges. Not quite familiar, either as themselves or as an arrangement of objects. I had a sense of items poised in a museum, absorbing my attention while contriving to escape it utterly. Clear and hunkered as they were, I couldn’t quite see them. I realized the date was April 26 2007. The same day as the Guernica attack, exactly seventy years later.

The bombers had appeared in the sky at 4 p.m. I looked at the homemade wooden clock on the end table. Hand-sawed and painted yellow-green, it has the shape of a tall, slim house with no windows and, at its base, a little red door askew on its hinges. The hour hand had dropped below the eave on the right, two thirds of its way toward the crooked little door. The big hand pointed straight up into the peak of the tall roof. It was 4 p.m.

For a long instant, like the sustained vibrations of a musical chord, past and present collapsed together like the two ends of an accordioned paper figure. Or more than two: the moment thronged with splintery harmonics. Stretched out, the two sequences–the destruction of a town, which became the subject of a famous painting, which became the subject of an essay; and (reversing things) my reading of the essay about the painting about the destroyed town–were separated by the innumerable twists and folds of seven decades. Then somehow, with a speed that gave me vertigo, they shut up tight together, without a wafer of space between them.

They overlaid each other like clear transparencies. That was part of the vertigo. As if the intervening seventy years had suddenly gone sheer and negligible. Like wandering (I was looking at the house-clock again) in a building made of glass. A glass construction polished to such speckless transparency that things that ordinary walls and floors and ceilings would keep at a distance could suddenly loom, merge and blend.

But there was movement in that image. There had to be. In part to account for the lurching, jittery sense I felt lying there. A sense of caged turbulence–wild whirling bounded by absolute stillness–like the frenzy of snowflakes inside a glass-globed paperweight.

A dance, I thought. In a dance you whirl through space without ever leaving the dance. At a given moment someone may be across the ballroom, or right next to you, or in your arms–these positions and others can repeat and alternate. All of these thoughts and comparisons, none of them quite right, none of them completely wrong, could go on without any disruption to the dance itself. Perhaps they were even part of it. A step, a style of stepping, however ungainly, that I could claim and recognize as my own.

For if the pure exhilaration of this kind of dancing has always come with close echoes of apprehensiveness, it is not just because of its weightlessness and the transparency of its figures, those unmoored glassy possibilities that bring havoc just as easily as redemption to the world of solid sense and obscurity. It is because, once finding myself aswirl again, I have never had the slightest clue when or where or how the dance will end.

__________

After that there was nothing for a few days. Then the first transmissions, widely spaced. The number 70. Lines and circles scratched in dirt. My grandfather. These could be core signals or peripheral or preliminary, perhaps to test or clear the line. There was no way to tell at this point. I knew by now to do nothing but wait.

__________

In July 1963, John “Jack” Green, my grandfather on my mom’s side, died suddenly of a heart attack, aged 70. I was seven, almost eight, at the time. Ever since then, his death, as Mom described it to me, has been the model in my mind of a good death. The sort of swift and summing exit not granted to many. He was a gentle, churchgoing man, worn but not broken by working a Saskatchewan wheat farm for fifty years, including the worst years of the Depression. His father had been one of the first eastern settlers to build on the land outside Moose Jaw. On the last day of his life, my grandfather came in from the field to have lunch. He was still vigorous, still active in the pattern of his days.{{1}}[[1]] Once he sent me an arrowhead he’d found in a furrow. Busy as he was, he took the time to nestle the artifact in cotton in a little box, and to write a description of how an Indian hunting buffalo might have lost the arrowhead many decades, even centuries, before. It was a perfect arrowhead: notched at the base, whitish as with frosting on one side, semi-translucent on the other. For years it was my most prized possession: kept close in its box on a shelf, where I could observe and fondle it daily. One day it disappeared. Stolen, obviously. Those around me speculated about the small number of suspects who had access to my room. But I, though I mourned the loss, had no interest in the thief. Already I knew that there were holes in the fabric of life through which things slipped unaccountably-reality a sieve whose mesh gaped frequently before compacting I barely thought of the theft in human terms. When I did, conjecturing who might have robbed me, I felt, more than anger, a kind of queasy cosiness. Certain thefts, like spontaneous gifts, constitute an increase in intimacy, an unasked-for gloss by others on our lives. Ordinary rip-offs and pilferings, even online “identity theft,” are not the activities of the Close Thief, as I came to call the arrowhead stealer. This Thief does not acquire, but proceeds from, intimate knowledge of who you are, what you value most. I have lost three possessions to the Thief: the arrowhead from my grandfather, a beaver skull I found on a beach, and a German edition of the poems of Charles Bukowski that, apart from a tourist brochure of the Blautopf (see below), was my only tangible connection to the time I spent in Germany before going insane. In each case—instances spanning about a dozen years—the Close Thief went for the artifacts I clung to most dependently, vestiges of a vanished natural and personal history.[[1]] “I feel tired, Maudie,” he said as he settled into his chair. “I’m just going to close my eyes for a bit.” When my grandmother came back from the kitchen, he was gone. Sitting with his eyes still closed, his hands still folded; no signs of pain or panic. As if, having reached his Biblical allotment of threescore and ten, he was permitted to depart peacefully, like a ploughman who has faithfully cut the long furrows back and forth in a vast field and can now, having reached the far corner, leave the implement and slip into some nearby shade for his rest.

But similes, like everything else, depend for their meanings on the frame that bounds them, on how far they’re allowed to go. Meaning is a bonsai operation. If the ploughman image is permitted to extend even slightly, there is, for the one back in the farmhouse, the matter of the abandoned plough, which must be dealt with, and the mystery of the vanished labourer. My grandmother, Maude, whose maiden name of Bastedo reveals her Spanish ancestry, had to wait eighteen years to follow Jack. She sighed sometimes, more often as the years passed, “I’m tired. I want to see Jack again.” Or, “I’m ready to see Jack.” Her hint of exasperation at the length of the vigil she was being taxed with in no way contradicted her legendary Christian faith, cheer, and kindness to others. It made these qualities shine even brighter, as the foil of stoical resignation in which these gems sparkled. She continued shopping and cooking for the sick; volunteering at the church; visiting and telephoning and writing her seven children; sending each of her two dozen grandchildren a card with a note of love and a green dollar bill on our birthdays–these are only a few instances of her charitable heart, which was energetic and constant. Her death was as sudden and in-stride as Jack’s. Literally in-stride in her case, as her heart gave out while she was walking home from church, struck down, as Jack had been, while active, while attending to what she loved and believed in. She had called all of her children on the telephone the night before. The first time since Jack’s death, they realized at the funeral, that she had phoned all seven of them on the same night. Several of them had heard her say, “I’m tired, I miss Jack,” as close to a declaration of impatience as she came. The yoking of “tired” with the certainty of a glad reunion makes of death a falling asleep, but also a waking into the better world that her faith assured her would be waiting. Leaving a muddled waking dream, which, even to someone of Maude’s devotion, the cheerfully executed but repetitive rounds of her long widowhood must have seemed sometimes, to awake in a perfected dream, lucid and permanent.

I remember, on that spring night in 1981, crossing the kitchen to where Mom stood with her back turned after replacing the phone. She faced the corner, her shoulders furled with the start of grief. Then, my only thought was to comfort her as best I could. Now, though, looking back, I think beyond this to the story she would soon begin murmuring, of the closure of her mother’s long vigil, like the dangling end of a long necklace or locket chain that had finally found its clasp. And I think, too, of my own situations in 1963 and 1981, and find differences and parallels, which sometimes switch about and become each other. At almost-eight, in 1963, I was about to enter Grade 3 in a new home in a new city. Eighteen years later, I was living in a small room downtown (I had walked up the escarpment stairs to have dinner that evening), washing pots in a kitchen by day, writing poems by night. I wrote and read and walked much of the night, sometimes skipping sleep to have a last coffee near the kitchen before my shift started at 6 a.m. I wrote on average several poems a night and mailed them to magazines around the world, which in turn mailed almost all of them back. More than happy, I felt awake. Finally awake–as if my whole life before psychosis had been a fever dream I tossed in, a swampy swirl of lulls and jolts which had to accelerate to a climax before the fever could break and my eyes open.

Grandma Green was the last of my grandparents to die; her death closed the clasp of that generation. Grandpa and Grandma Barnes, residents of an Ottawa nursing home, had died, a few months apart, in 1977-78. I was in hospital at the time–often catatonic, I have been told and have no reason to doubt–and remember nothing of their passing. When I was discharged finally, in 1979, those two elderly people I visited as a child were simply not there anymore. The photographs of their gravestones declared an absence without making it real. It was as if, while I was “away,” my grandparents had been abducted by aliens and whisked to another planet. That was the way it would have happened in the sci-fi books I devoured in my early teens. Interplanetary agents might have been left behind to plant evidence explaining the disappearances. Such stories no longer held allure for me. For some years now I had been living a life replete with inexplicable transports and lacunae. The aliens were here, their work was everywhere. Except that I no longer believed in aliens. Or perhaps it is truer to say they no longer interested me. Their myriad crazy doings had exhausted me into indifference. I was drawn now to “realistic” authors, though their realism was for me a risky realm. Authors who wrote of characters whose lives evolved by discoverable cause and effect, linked chains of relationships and events, remembered as a chronological continuity–these authors, who were in the majority as I discovered, wrote tales no less fantastic than those of Heinlein or Philip K. Dick, but for far higher stakes. Those stakes were nothing less than the establishment and maintenance of an order of ordinarily fathomable life. An audacious goal. A hopeful and necessary one, it seemed to me, crucial and heroic. At other times I found it deluded, craven, even obscene. My reactions to realistic fiction were extreme because its stakes, for me, were extreme. They were, in fact, ultimate. I needed to believe, despite overwhelming evidence to the contrary, that my own life followed discernible patterns, that events happened for reasons and that similarly solid people with their own evident trajectories–rather than phantoms whose visitations were random and unknowable–intersected with it. That personality was more than a series of poses or mirages, persuasive and evanescent. My favourite authors gave the devil his due. That is, their fictions allowed for unexplained personal obsessions and drives, random and even magical occurrences, but they incorporated these irruptions into a skein of narrative causality. Knut Hamsun, Brian Moore, J.G. Ballard, Isaac Singer. Emotions like meteor showers; fluctuating spells of death and apparitions of the virgin Mary; the world’s cities sunk in deep lagoons, a car crash love cult; dybbuks and succubi and eunuchs mad by the full moon–but between these marvels, admitting but also denying them implicitly, the linked words and phrases of plausible action, reaction, sentence after sentence, page after page. The world of sense; of linked, constituent parts. A tractable creation. A submitted one.{{2}}[[2]]In those early days out on the street my writing diet was more omnivorous than my reading one. Mixed in with poems on rivers and rain, scrambled eggs and streetfights over strippers, were more fantastic productions, flowering visions that jolted me awake and were elaborated in rapid scribbles over three or four pages. One I remember described the huge winged creatures (whose name I have forgotten), tentacled like octopi, who raided our dimension to suck the life force from humans through their eyes; the people one encountered on the street, most of us in fact, were the remains of their depredations. Where to send such a poem but to the antipodes, as far from home as was geographically possible? But Poetry Australia, though they had previously accepted a short poem synchronizing the flowering of a hawthorn tree with the life of Heinrich Himmler, returned this one without comment.[[2]]

The pine tree. Chedoke Public School, when I started there in the fall of 1963, first placed me in a Grade 2 classroom instead of Grade 3. We had moved to Hamilton in the summer and perhaps my records from the old school were mixed up or delayed. In any case, what cracks Mom up when she tells the story, which she finds both appalling and hilarious, is the interval of several days during which I kept silent about being in the wrong grade. When I did speak up, I burst into tears, all my throttled misery spilling out at once. But she finds curious the time when I kept stumm about my demotion. Taking my seat in the out-of-date classroom, conscientiously completing last year’s work. She finds that remarkable. I find it typical, and an augur of sorts. I would have kept quiet partly from timidity, but also from a conviction, which dates back as far as I can remember, that all powers are completely arbitrary. Unaccountable and inexplicable, they do with you what they will.

That was certainly the case on the playground, which seemed to me an extreme classroom, its rules warped to multiply thrill and terror. Behind the school stretched a plain, vast to my eyes, of patches of stubbled grass surrounded by hard pale dirt pounded flat by hordes of running feet. “They’re coming!” the cry went up, as we played Red Rover or British Bulldog in the grassiest, softest-for-falling area; and across the plain, as we stood gaping, a dust cloud roiled toward us, like the dust of a prairie stampede. We milled together, like zebras or antelope before a lion attack, and then, just as in the animal documentaries, scattered in all directions as the bullies converged to pick off their targets. I was seldom damaged, except collaterally, when a whole storm of bodies crashed together. I was middle-sized, with a middle expression: neither big nor small, bold nor visibly afraid; not ostentatiously “different” enough to constitute a challenge or an obvious victim.

The most different person was never attacked. Neither by the bullies nor by their whimpering victims, who often, in the aftermath of an assault, turned on one another. Everyone seemed to understand on an intuitive level that extreme difference breeds strange powers and entanglements, magical complications that transcend the laws of physical force. To cross far enough over was to be inviolate, though at the price of utter isolation.

Paul Tamburlaine. What do I really remember of him? I don’t want to stitch him together with imaginary threads. Watery, rather expressionless eyes, pale gray infused with the faintest blue. A wide gash of delight, that split his face at odd moments, for no apparent cause, exposing a wet red mouth and large crooked teeth. Thin arms with large clumsy fingers. A slow, lurching walk. I remember more of him than I thought; he is coming into provisional focus. His most obvious feature, so obvious that after a while you seldom noticed it, was his greatly enlarged head. Bulbed at the forehead and behind, it suggested the shape of a light bulb with his face in the narrowing part. His swollen head, still swelling, was the result of a fall from a tree when he was younger; that was the story that circulated.

Paul sat or stood at the perimeter of things. He seemed content there. His desk was at the back of the Grade 2 classroom, moved a few inches closer to the corner so the teacher could squeeze by when checking the other students’ work. Colouring with a box of crayons is how I remember him spending his time. He was larger than a Grade 2, and perhaps older by a year or two; Grade 2 may have been only a convenient spot to keep him, or perhaps it was the place he’d been when his accident had arrested his progress. Outside, he stood by the sidewalk at the far edge of the playground, scratching, with a stick he’d found, things in the dirt. He watched us at times, that sudden grin baring the lurid mouth, but usually just stood with his head down. He could talk, and reply to simple questions, but he rarely spoke or was spoken to. His voice was unnervingly high-pitched; there was a screeching note, a hint of frenzy, present even when he was speaking quietly. From time to time, a new student would invite him to join a game. By the firm shake of his head, No, it seemed he had been told not to play, perhaps because of further risk to his head. He was often away from school, for medical appointments we were told.

For a time, Paul was my closest companion. Not at school, where such a blurring of categories would have subjected me, not Paul, to violent censure. Paul seemed to understand this, grinning my way only slightly more often than before. But his house was on the way to mine, and I often went to his yard after school. My parents, if they noticed this at all (they were busy, their fifth child on the way, and I was already an expert evader), might have construed it as a way of adjusting to a new milieu. Paul’s mother (I never saw or heard of his father) was more concerned, parting the front curtains to peer out at us. Calling sometimes, “Pa-ul?”, whereupon he would go inside for a few minutes and then rejoin me.

Our minutes together–or hours, since they seemed timeless–were some of the most peaceful I have ever spent, and even to think of that short autumn launches me on a wave of nostalgia. Curiously, since those intervals were almost completely wordless, it is most often while writing that I approach the same borderland of poised stillness, a kind of scooped-out expectancy, that makes me think of Paul. Though his mother may have wondered at my motives in befriending her brain-damaged boy, I was simply drawn to him. I liked his otherness and his quiet occupations. I liked his silences and the occasional grating cries that punctuated them. They meshed with my own most natural inner cycles of revery and happy accident, and many years later they would return to me as early prefigurations of my notion of sanity as a perpetual guerilla action, raids on incoherence.

A big pine tree dominated Paul’s front yard (I assumed it was the tree he had fallen from), its bushy sweeping branches shading half the lot, creating a cosy grassless circle of needles and dirt around its base. Paul would be in there, among the sun-and-shadow patterns, drawing marks with a stick. I stood nearby, watching him. The things he drew were always the same. Or they were meant to be, I think, since his physical awkwardness and the resistance of the dirt sometimes skewed them out of shape. They were the same symbols he drew everywhere. (Except in class, where he crayoned clumsier versions of the generic landscape we had all learned: sun, cloud, grass, tree, house.) He drew a stroke across from left to right, then a longer stroke down starting at the first stroke’s right end. To the right of this first figure, he scratched a circle, concentrating hard to do so without lifting his stick. Of the three strokes, the circle was hardest, often wobbling out of course around a stone or hard clump of dirt. The resulting shapes looked roughly like the number 70. But only roughly, since the angles of the first two strokes and the size and position of the circle were so changeable. They could also look like the number 10, since Paul sometimes dug his stick in hard, grinding it back and forth fiercely, at the bottom of the second stroke.

I’m thinking of Paul’s marks as numbers now, to describe them. I don’t remember doing so at the time. They were just Paul’s marks. They were his voice, really, more focused and more personal than those strangled yelps he emitted. Milling with the other students at recess, before or after the bullies had attacked, I would look across the schoolyard plain and see Paul at the edge, head down, drawing with his stick. It was comforting to know what he was drawing, as if I was there while standing here, and especially, to know that he was drawing. The tasks of school had already thrown the rest of us into an oppositional sloth, an ostentatious indolence to counter our enforced diligence, but Paul had escaped this teeter-totter of rote and recoil. He was always busy in his own world, etching his intentions upon it, like the much younger child the rest of us had already left far behind.

Fights between bullies, which happened once or twice a week, took place against a red brick wall at the back of the school. I almost said were staged, since this wall of bare, chipped brick, its putty darkened with graffiti the janitors couldn’t scrub off, was the perfect backdrop to the spectacle we watched from a crowded semicircle. The combatants were sealed in between the brick and the packed onlookers. Usually it was two of the minor bullies fighting, perhaps to settle a dispute or advance their standing; we knew nothing of the inner workings of the gang. Every so often, though, as the climax of a cycle in which the minor fights were epicycles, the two main bullies fought, a treat that was announced in excited whispers for days beforehand. Moose and Hackney exchanged places regularly as leader of the bullies. The fights were real: flying blood and snot and curses, smashing fists and feet; but their prize seemed more symbolic than real. The one who was not leader afterward was his close subordinate, almost equal in power of command, and was alone in being immune from the leader who had just narrowly defeated him and whom he would soon narrowly defeat…an endless cycle. Endless, at least, until they turned sixteen and could finally leave Grade 8 where they had strutted and fought for years. Moose and Hackney. They were like contrasting types cast for a western, interchangeable as villain and hero, but visually distinct for the viewer’s convenience. Moose short and broad and blond, Hackney tall and skinny and black-haired. Both wore nosepicker cowboy boots, for clicking and kicking.

Standing among the youngest students at the rear, I would look away from the din–from the back it was mostly an auditory event, a tumult of screams and thuds and the special crunches that brought deep-bellied groans of pain and appreciation–and see Paul over on the edge of the playground, his stick dangling from his hand, watching us. Or watching the place where the noise came from; his posture seemed attentive but not curious. His position looked so peaceful. Occasionally a car passed behind him, the only motion on those streets of silent bungalows. At some point–I don’t know when it started or in what terms I conceived of it then–I understood that Paul was the most powerful person in our school. I don’t know if it was a thought, I don’t know if I had thoughts then. Year later, in my sci-fi phase, I might have imagined Paul directing the proceedings, all of us, with thought-beams. It might unfold that way in a Twilight Zone episode, the nobody on the margins who was actually the alien in command. But this was far less conceptualized; it felt like simple recognition. It was also a longing, an intuitive attraction to Paul’s weird and singular privilege. Bullies traded places; Paul kept his. No one bothered him: not students, not teachers, not even the principal. Bullies, I noticed, even Moose and Hackney, slouched past him as if he wasn’t there, feigning obliviousness instead of inflicting it. Sometimes when they passed Paul I caught a confused–almost a lost–look on their faces. Those looks disconcerted, and hinted at something thrilling. Their power fell away from them in an arena in which it had no meaning. I couldn’t begin to understand any of this. At that age all motion, all awareness, was merely magnetic: I never decided to move, only felt myself moving, creeping toward some things, inching away from others. Things and people approaching or receding told me I was moving.

Whatever this dawning revelation was, about Paul and about power at the margins, I knew enough not to tell it to anyone. I kept it close and secret, something to nourish and prove my allegiance to, much as a sorcerer might add each new herb he collects to a bundle tied in a leather purse that he hangs inside his clothes, next to the private heat of his body.

Sometime that fall, Paul left our school. He may have lived at home for a time without going to any school, because I have a few memories of passing his house and seeing him standing near the pine tree with his stick. I didn’t stop anymore, and he didn’t raise his large pale face as if he expected me to. By then, by processes occult to me, I had been absorbed into the normal life of school where I was beginning to excel.

Paul was gone by that late autumn day when a great adult excitement communicated itself to us and we were let out of school early. Everything seemed chaotically off, festively traumatic, like a daytime Halloween. Kids milled around in unusual knots, a goofy boy with red hair ran around at top speed shouting, “The King’s dead! The King’s dead!” We waited for our mothers to pick us up, even those of us who normally walked home. Some of the mothers in the station wagons were crying; two of them got out and hugged each other. Paul is nowhere in the scene, but some essence of him clings to what I recall, blended with my activities as if I had absorbed him, as if we were now one person. Lying on the living-room floor for the next two days in front of the television which was never off. My parents smoking and talking in low voices. They talked mostly about the king with the huge head, and the little man who had killed him. By now, of course, I knew the facts behind the redhead’s leering cry, “The King’s dead! The King’s dead!” But his version, like a peasant’s shout in a fairy tale, still seemed truest. Black horses, one riderless; cannons; the avenue thronged with weeping subjects; the beautiful veiled queen: what were these but the trappings of a dead King? Lying on the floor with my paper and crayons below the hanging smoke, I drew a version of Moose and Hackney, but the colours and proportions were wrong. Plus, I couldn’t draw a gun. Then, at some point, I got another idea from the pictures on TV. The bullets that blew the king’s huge head apart came from high up in a corner, so far away that the little man in the window with his gun couldn’t be seen, a man in a tie had to draw a circle around the spot. And then when the little man himself got killed, again it was by an arm coming out of the corner. My first three months at Chedoke Public School, and Paul in particular, had prepared me to understand this. The adults were always talking about the man in the middle, but all the real power was over at the side, almost out of sight in the corner. That power could blow a king’s head off, snatch a prisoner from the arms of big policemen. From time to time, I glanced up warily at my parents. They seemed utterly absorbed in the TV accounts, never hinting by a look or comment that they doubted them. Didn’t they know the power was at the margins? Or did they know and pretend not to? Both possibilities unnerved me, and I ducked back down into my drawing, shrinking my world to paper and coloured wax. Finally, I found a way to hint at what I was seeing. It didn’t convey my understanding but it gestured toward it. I filled in some patches of gray and white, mixed with bits of beige, in the middle of my page. It looked like a muddle of ragged clouds, a jigsaw fog. Then, over in one corner, I put a long black bar, with a short red bar coming out of it–like a figure in black with a red hand, or gun. I made the red and black lines as strong as I could, pressing over them again and again until they gleamed darkly. I kept redoing the drawing, changing the sizes and configurations of the centre shapes and the corner figure, trying the latter in different corners for instance. I could never get it quite right, but I liked the general effect. It was the kind of thing I wanted to do more of.

Next I became aware of my watch malfunctioning. By “next” I mean not just the next step in a sequence but the next signal from the same transmission. If you are making your way through a forest, the way may be easy or hard, but neither case is like coming upon a cleared path laid out in a direction that beckons you. And if, a little later, the path breaks down, petering out on rock or becoming choked with deadfall, then pressing forward in what you construe to be the same direction is nothing like the way opening suddenly underfoot and up ahead so that you find yourself on the clear and shining trail again.

My watch was breaking down, but not all at once and not completely, which for a while prevented me from repairing it. I would notice it was running two minutes slow, then an hour later, another minute. Okay, I thought. Would set it to the radio and check it six hours later. Perfect time. Two days later, still perfect. A bit of dust inside the works? The next morning it would be five minutes behind (it was never fast). This was in early May, soon after the Schama/Picasso overlay, and I took it to be part of the same dance with time. It was an instinct that kicked in about certain symmetries coalescing, which led me to issue myself mental reminders: Take note. Stay alert. (“Stay frosty,” a movie marine would have growled.) I started keeping my watch in my pocket, it was less unnerving than having the uncertainty on my wrist. I asked people what time it was. People I was meeting. Then strangers. Most replied politely, but a few gave me sharp looks, this beggar bumming time instead of coins. The results stayed variable. Right on the dot. A minute off. (It was never fast.) A half hour behind–now we’re talking! Dead accurate for the next four days. Always this nagging little drama, this stutter-step from a Beckett notebook: breaking (or?), must break (or?), stagger on (…or?). When I finally took it to a jeweller in a mall, it wasn’t because the watch had definitely died (though what would that mean? it had lain dormant for up to an hour–why not a year?), but because I was sick of the space it was occupying in my mind.

I stared at the glitter of expensive watches under glass while the sales clerk finished with another customer. She frowned when I stated my problem. One of those natural young Mediterranean beauties–big dark eyes, chestnut hair, slim, she would have stopped your heart drying her hair after a shower–who had smothered herself in makeup and floral scent. She limped in her stiletto heels. Why do that? I thought for the thousandth time.

She came back and told me that the battery was fine. I was prepared for that possibility, though still a little surprised. A cleaning? I inquired. No–she gestured at the door behind her; I saw a little man, bald, bent over a cluttered desk–he said it was fine, no dust. I stood there stunned, my not-dead watch in my hand. The hand she laid on the counter had inch-long, curving nails the colour of Wite-out. Did I want to buy a strap?

All the transferring between wrist and pocket had cracked the old strap almost through. Her father–some shared liquidity in the eyes when he turned to her–attached a new brown leather strap to my failing but not failed watch. For a few days it kept perfect time.

__________

The laws of breakdown. Its code. Which you must on no account violate if the breakdown is to be yours (and of what use would another’s be?). Perpetual vigilance is required, the paradox of rigour amid crack-up (which is in fact no paradox but a necessary condition). What you don’t want above all, the worst betrayal–of the process, of yourself, of life even–is a botched breakdown. One of those tape-and-glue stumble-ons that can simulate recovery, functionality, can even, with a protraction that a Torquemada might flinch from inflicting, extend themselves into a slow-motion suicide lasting seventy years or more, “sadly missed.”

No. (That much you know.)

Eventually the watch will stop. Or you will smash it: that seems daily more likely. Beyond a stopped watch will be…no time or new time. But not fractured time. Not these splintered and dissolving minutes.

Beware of watch-repairmen. Tinkerers. Parts-replacers. Let the watch break.

(And yet no way to tell, from the first slip-slidings out of time–or the first noticing of them, for who remarks on a few dropped seconds?–how long it will take a watch to break. Days? Weeks? Years? More time than a lifetime affords?

To smash, crash, stop. And become…time-less, bare-wristed? Or tell time true, anew?

Or be tinkered back to passability? Fiddled with and spit-shined by the old, bald man?

No way, ultimately, to know.)

__________

During my first year at university I dwelt in a kind of twilight state that I called a waking dream. This state was so strange that I assumed it could not last long. Yet it would last another three years and lead not to the death or awakening I expected but only to long-term hospitalization. It wasn’t like a dream, not really, but it wasn’t waking life either. Perhaps “waking dream” is really the best way to describe it. Precisely imprecise.

I had trouble telling the time. Clocks and watches told me one thing, but my eyes told me another. It might be noon but the colours were leaching from things and a grainy veil drawing over them (early on I’d blinked and rubbed my eyes a lot)–as if the world had been sketched with almost-dry markers, then photographed out of focus, then a machine had blown in fine gray specks, sand or soot, that floated and sank–I piled up the scenarios that could conjure the faded, sleazy dregs I was seeing. And it went the other way too. Out walking at 3 a.m.–I took these epic tramps to try to exhaust myself into sleep–I’d pass another night trawler and see features shining in a boom of light, pinned under a glare in a Dali desert. Sometimes despite myself I stopped and gaped, startling the other into a jog, glancing back over their shoulder. And I looked about for the streetlight or passing car responsible for the light-burst. But there was nothing. I was standing on a darkened street, the footsteps pat-pat-pating away.

I tested my eyes in the mirror. Even if something wasn’t seriously wrong with them, maybe I’d developed a tic of staring and then squinting; my own lashes could be those grainy veils I seemed to be peering through. It was only a slim, desperate hope, which I didn’t really believe. Otherwise why did my guts knot as I approached the medicine cabinet’s mirrored door? I’d learned to wash and brush and shave without looking up except in slivers, spotting the part I needed to clip or dry. Now I looked straight on, eyes open. Black. That was the first thing I noticed. My eyes couldn’t be called brown, even dark brown, anymore. Black buttons, with a plasticky gleam; sunk in gray puffy folds. But they were open. And still the light from the forty-watt bulb flickered up and down, like someone twiddling a dimmer switch. The face in the glass frightened me. It was a mask behind which great error was occurring. Sometimes I thought of the error as evil. There was a moral dimension–that somehow I had chosen this–that I couldn’t shake.

For long hours, twisted in the sheets of my roominghouse bed, I lay in a swamp void of volition, twitching my hand or foot to be sure I wasn’t actually paralyzed. I had left my parents’ house abruptly, taking my shaving kit and a few clothes. Not just to be free of them –I was 18–but to find a quiet place where it could happen. I felt a shame about what was coming and for as long as possible I wanted it to happen out of sight. Some animal instinct for the time for crawling away. I never lost the sense, even when the turns got frankly terrible, that there was a knowingness, some cruel wisdom, guiding the process. Something ancient knew all this, perhaps had coded it through millennia, and had procedures even in the midst of chaos. That kind of thinking irritated the interviewers later. They wanted me to say it was all bad, all symptom. Pathology to be chucked while I steered toward health. And I couldn’t, quite. It wasn’t stubbornness, nor courage–I was terrified. Sickened and disgusted and mesmerized by dread. But to give up all glimmers of knowing, of sensing landmarks and direction–where, what, would that leave you? Even in the blackest mangrove swamp, sunk there on a moonless midnight, you had to claw-squelch-flail-inch toward something–you couldn’t just hang there. Why couldn’t they see that? I’d stare at them they must have written), really trying to figure it. But that was all up ahead.

For now I was nothing but symptoms. Such a profusion of them it paints a false, too orderly picture to give these examples. Symptoms like an anthill, boot-strewn: cognitive, affective, behavioural. Physical, metabolic: hair texture, skin tone, digestion–all wacko. A total stone{{3}}[[3]]Doing drugs brought temporary relief and then a longer sadness. Acid, mescaline, grass, hash: they gave reasons for things to be altered, though even so the alterations were milder. And others to be altered with—though they would not be altered in the morning. Would just be grumbling about coming down, reaching for the Cheerios. People naturally assumed I was doing more drugs—at a glance I might have passed as a stoner—but the small relief wasn’t worth the loneliness, and I was doing them less all the time.[[3]].

Except that I didn’t use the word symptoms, not to myself. It wasn’t my word. It was something more like travel, a process unfolding. And so close I didn’t need to name it. A secret knowledge that I grew to call a pregnancy. A pact. An interior pact of tremendous vitality. Vitality and risk, a doomed cellular glamour. Soon, I’d think. We’re almost there. It’s coming, not much longer. It’ll be bad, really atrocious…but then it will be over.

All these steady mantras to get me past the moments.

There were gaps. Blink-outs. There must have been, because I’d find myself somewhere–in a park, on a street, in a room–with no memories of having got there. I’d think back, hard. Like a math problem. Standing in a park. Winter. Snow, stars. Back…the coffee shop. Low light but not dark, more like dusk. Hours ago, then. An hour or two at least. What else? Try! Nothing. A blank spool between then and now. I wasn’t there. Not in my own memory. Where was I then? (Where am I?){{4}}[[4]]Absence seizures, more common in childhood and caused by a mild impairment of the interaction of the thalamus with cortical gray matter, produce a momentary clouding of consciousness, as when one stares at a bonfire or blank wall. They correlate with brief but abnormal patterns of neuronal firing that may originate in the intralaminar nuclei of the thalamus. But departures on the time scale I experienced them—hours, occasionally days—would have to be called fugue states, I think. Even a series of absence seizures over a short time would presumably leave some fragments of recollection between them.[[4]]

I didn’t invent The Autopilot, I said testily, one of the rare times my voice rose, in one of the offices later. (The pen scratching its evidence, the pissy prim posture.) I simply gave a name, an obvious name, to something that needed one. Someone–Something–was moving me from A to B. A phenomenon. It matters, so you name it. Right?

When it wasn’t rinsed by radiance–the Illuminations were becoming less frequent, something settling down, locking in–the world looked wretchedly dirty. Grime spattering the window glass. Streaking the walls, the floor, the ceiling. Hanging in filthy webs, putrid decaying streamers. Everything was grime. I was grime.

I’d forget to eat for two days and then shovel down a pot of Kraft Dinner at 4 a.m., gobbling it over the filthy stove. Wander along wondering seriously how I could be feeling so cold, whatever happened to the warm blood of youth and could I really have lost all muscle tone that fast, then notice, like a sign posted in the corner of my eye, an icicle, and then another notice, my red T-shirt, bare arm. February, I’d remember. And sometimes burst out laughing at such times, not always crazily, sometimes just a really warm chuckle at how goofy it had all got. What rich meaty veins of antithesis you have, Grandma.

I knew enough to steer clear of people. I moved through McMaster’s campus like a ghost through a fleshed town. I was especially afraid of meeting former classmates, afraid they’d try to talk to the smart affable guy they’d known and we’d both feel weird, so I found a lot of back alleys and unused stairwells, kept my head down. There was a system inside things, I found, a sort of parallel architecture that allowed you to stay invisible and still get where you needed to be, ghost routes so dependable they seemed as planned as washrooms. I assumed I looked awful, a real ratbag out of Dostoevsky’s notebooks, and was shocked sometimes when a normal-looking person gave me a smile or a nod, chatted to me in the coffee line. Was it all invisible? I couldn’t believe it for long. Especially, I worried about the two dimensions meeting, inner and outer, ghost and flesh–I imagined something like the matter/antimatter cataclysm in Star Trek. Even a slight leak could cause a lot of local damage. I think it may have happened once. There was a girl–very intelligent-looking, with kind eyes and a large hooked nose–I kept running into. I’d catch her giving me these sad, strangely pointed looks; searching glances, as if she knew me partway and couldn’t figure out another part. I started seeing her more and more, and the looks became more intense. Meeting them with what I thought was a neutral expression, I would see her jerk away suddenly, as if she had burst into tears or was about to. This went on for a time, the tension of our meetings mounting, and then–I don’t think I called them transmissions yet–some pictures came into my head. She is looking up at me, we are dancing a slow dance, just circling slowly in a crowd, she is smiling, her eyes warm, and I feel the dampness of her blouse where I am holding her. Her name flits near, like a word on a passing radio, and then is gone. And then her face again below me, in shadow, in a bed, she is holding the covers over her breasts and I see the white glow of her chest, a dark flush at the base of her throat. She is frowning slightly. She looks puzzled, angry. She is trying to figure out something that is hurting her. Where am I? I must be beside the bed, from the angle. That was all. But now that I’d seen them, the pictures stayed, strong and consistent. And they made a kind of story that went with her stricken, resentful looks. Had we really met at a pub, gone to her room? And then I’d forgotten the night, forgotten her? How awful. There was real damage here. The gaps so complete, anything between them possible. And no way to tell her, no way to explain. She’d have to be with me, all the way in, sharing our lives. And I was far beyond that (or before it, below it, really). It did flicker in my mind, a flitting hope like her vanished name, which for a short time made our chance meetings even more charged. Stay away from people, I told myself. And then I stopped seeing her, we never met again. I still think about her occasionally, wonder what really happened. Where she is now and what she made of it then. The pictures separate and distinct as ever. Still no name.

I knew I had to quit university, had to make it official, but I still dropped in to classes once in a while, read the odd page. Showed up for exams, handed in papers–I must’ve, because my transcript lists low Bs, the subjects passed. I don’t know whether that proves how little Arts programs were asking even then, in the mid-70s, or how ripped my academic muscles had become by senior high school, so that I could coast for a long time while they turned to flab–both, probably. I recall almost none of it. If interrogators put a gun to my head and ordered me to write down everything I remember from my first two years of university, only true memories no lying, I couldn’t fill a page. Not with school memories: classrooms, teachers, other students. Things I read. They didn’t happen. Not if memories equal events, they didn’t. The coffee I just made happened more.

One note on the page. No date. A philosophy class. The grad student, a tall beard, is trying to impress us with first-year conundrums. The tree in the forest. How do I know I know. When he gets to the one about the Chinese philosopher who dreamed he was a butterfly, and ever afterward wondered which he really was, man dreaming butterfly or butterfly dreaming man, the students chuckle drily, an emission of mild irony. That rouses me. I say something to the effect that obviously they’d never had a sufficiently compelling dream. No other storyline had ever tempted them. Something like that; probably in a rusty, too-loud voice, since the heads jerking around is a sharp image. I must have been slouched in a back corner, the Raskolnikov seat reserved for the shitbird who drifts in once a month to sneer at the proceedings. The beard shoots me a look of appreciation: a baby Nietzsche I can nourish? Then a cold remorse and shame washes over me, like a cup of icewater I’d tried to dash in people’s faces and it had blown back in my own. I feel awake for an instant, really awake, and think, What are you doing here? You don’t belong with any of this. Get out, get out, get out. You’re way past due.

The dream of Liesl Annerkant. 1970. Grade 10. I look back on it as the zenith of my school career, because even though my marks climbed even higher in the next two years, some dispersal must have started too, it seems likely, for it all to fall away so quickly in Grade 13. Yet I know nothing of the timing, and only a little about the process. But a view of something that you know is about to break does not look solid; some awareness of the breakage seeps back into the earlier frames; you have to snip out quite a bit of infected film to get a shot that feels reasonably solid. And so, by subtraction, I arrive at the solidity of grade 10: a compact coherence, packing my bones and spirit tight together. A real good boy, young man. I have two close friends, we play Risk and penny poker. Sip whiskey, trade jokes and insults and sex fantasies. I join the euchre tournament in the cafeteria. Play road hockey behind the Salvation Army. I make the football team, not first string but I get in a few plays. None of my marks is under 80 and I am getting 98 in Math.

Liesl Annerkant, two rows over, is getting 100. She hasn’t made an error yet. Not one decimal out of place. Her perfect string creates a delicious tension in the room: Can she keep it up? Mr. Brieve, who has a sense of drama, draws out the moment when he hands back tests, approaching her desk with a blank face that kills us, not grave, not anything. We squirm. And then he slams down her paper, slaps it like a high-five on wood, face up with the three big perfect numerals circled in red. And a cheer goes up, it breaks out of us: “An’ she can!” The best we have been able to do with her awkward German name. And Liesl, not shy but not a gloater, lowers her head, peers with a frown like factoring at her own perfection, there is nowhere else to look, while two spots of rose glow on the back of her long, slender neck. She is beautiful. I can’t introduce flaws just to keep the picture interesting. Full-breasted, slim-waisted, long-legged; with a stern, straight nose that makes me think of Athena–and wheat-blond hair, long and centre-parted. And nice: not overly friendly, but always patient if someone needs help, smiling when you pass in the hall. Just an achingly good, achingly gifted girl. A perfect girl. Why shy from the word?

And, curiously, nobody seemed to have it in for her. Not even the girls. All the nastiness that ten years had taught us, all the endless petty battlegrounds that were school–something, her sheerness it must have been, lifted Liesl clear of all that. You didn’t hear catty remarks about her. You didn’t hear horny ones either. She was better-looking by far than any of the girls we lusted grimly after, degrading them in our convoluted jokes–but she didn’t enter our minds that way. It would have been like mating with another species. It must have been a kind of loneliness for her. This sphere of spotless admiration and goodwill that she floated in, untouched and untouchable.

In the dream Liesl and I live a long, rich life together. We share a small house. There are no children. My work is bureaucratic, some kind of applied science in an office, but Liesl’s gifts are still leading her to the heights. She is a star of pure mathematics, and a highlight of our days is her describing some exciting new aspect of her research as we make dinner together. Both of us frowning, and then laughing helplessly, as I try, and try, and finally fail, to follow some obscure point. Such talk! Of a depth and richness, a variety and constancy, that I have never imagined in my waking life. Pet jokes, gossip, even boredom, stale topics that bring aggravation, sharp digs. The whole shared life in words. Sex is there, delicious interludes, but even it is secondary to this consuming conversation. The dream’s resources are those of a master of exhaustive realism. No quirk or oddity ever feels imposed upon a scene, but none is overlooked if it is intrinsic to it–everywhere is the enthralling wealth, the minutely observed texture of the life we have together. If that life is so much richer than any I have known, charged with a shining meaning, it is because I am finally in life, draped in its fabric, attentive to every thread. I was conscious of this in the dream, without being conscious I was dreaming: This, this, is it, I thought, with gasping gratitude. This is how you do it. This is how it is. There is pain. Of course there is. Nothing is missing. Illness, heartache, disappointment. Betrayal, bitter words, tears. We even age convincingly, in tandem but differently: my hair thinning but staying mostly dark, Liesl’s going steely gray; me growing paunchy, soft, while she becomes leaner, almost gaunt. I comfort her in those moments, more numerous as she ages, when her confidence falters (“An-she-can!”). She comforts me wordlessly, with a look or touch.

Always, uniting all the multitudinous scenes, is our talk, the guiding current, this river of achieved communion…murmuring in the bedroom’s dusk, rippling and splashing in the yellow kitchen after work, pooling in wide silent bays…carrying, in all its sparkling surfaces and turbid depths, our whole vast history onward toward something unseen….

I awoke and lay very still in my bed. For a few minutes there was nothing but a sense of suspension and well-being, a warm bath of utter contentment. Then, in tiny increments, I began to be aware of other feelings, doubts and confusions like small stinging insects that were dragging me back into another, lesser reality. The dream was so alien to my real circumstances, my life as a 15-year-old boy. Which, in the wake of the dream, did not seem more real, only more threadbare. Like emerging from a long opera to hear some of the same tunes played on a kazoo. My rocketship bank on the bookcase, a gift from an aunt some years ago. The sounds of my parents downstairs. It seemed heartbreaking to be dropped back into this, cruel for the dream even to have shown itself to me.{{5}}[[5]]To this day I wonder whether the dream was a valediction to normalcy, to fitting myself satisfactorily inside the world with other people—or a prediction, a reassurance from some deep source, that that was my home and, after straying very far, I would return to it? A goodbye to, or a promise of, eventual sanity?[[5]]

Questions helped a bit. I could cling to the dream aura a bit longer through them, prevent it from receding too fast. How had a lifetime, two long lives, been compressed into one night? The best answer I could come up with (for the reality of the dream was too absolute to question) was that I was living that life in a parallel universe, where none of the same laws, including those of time, applied. (The aesthetic answer I would hazard now, that the dream director stuffed a scene so convincingly that it summoned others in its train, did not occur to me then.) Perhaps I could return to it. Do my time in this one, quietly, trying not to jar the portal, and slip back through. Perhaps even tonight.

Rain that had frozen during the night had coated the trees outside my window with ice, the trunks inside clear columns, the twig ends hanging in clear glassy bells. Light pulsed back from the crust, like clear shellac, on the snow. Liesl was out there somewhere, dressing in her room. I didn’t know where she lived. Was it possible she had not experienced the same dream? No. Telepathy at a minimum was what we’d shared.

Downstairs my parents were eating their toast, sipping their black coffee. Not talking, which I was grateful for. I got my cereal bowl and took my place. Holding on to the dream’s spell was a fragile effort, more precarious by the minute. But their silence and small noises, clinks and scrapings–they were suspicious, too. They brought back doubts I had had at the time of Paul Tamburlaine. The dream’s momentousness so filled me that I knew I was changed utterly. Could they really be oblivious of that or were they pretending to be? Were they actors or automatons?

I crossed an open field before I reached the streets around the school. The freezing had formed that perfect crust that allowed me, with delicate steps, to walk on top of it, on a film between ground and sky, above a piled fleecy whiteness that my occasional plunges through let me wallow in. In hollows where the water had pooled and the ice was thicker, I took three quick steps and went gliding, sailing, finally quite weightless. The air was still after the storm. Still as the inside of a bell.

In Math class Liesl was bent over her work as usual, giving no sign. The thin mockery of school life had prepared me for the moment, easing, in what seemed a self-betrayal, the pricklings in my stomach. Getting back was going to be more difficult, I saw, more occult. I would have to be vigilant. Who knew when I would return to the Reality Dream? (Never, as it turned out, at least not in the same form.) In the meantime, like a desolated scientist, I noted the differences between the dream and so-called waking life, to the radical disparagement of the latter. The discontinuity of time, moments like beads without a thread to join them. The confusion, the lack of purpose. Like a bunch of lolling, empty-headed actors who, out of sheer boredom, sometimes improvised inept little skits, then fell to dozing again. The adequate, undramatic light. The tinniness. The threadbareness.{{6}}[[6]]The dream as 600-thread-count sheet, which, while not more real than a cheap sheet, may convince one fortunate enough to sleep on it that this, really, is what sleeping is. It wasn’t that life in the dream was better than my life awake; it might have been worse. Petty disagreements, even tearful and cruel quarrels, were frequent in it, as were episodes of sickness and loss, wild barren grief. What made the dream so heartbreaking was its vivid continuity, its sense of a life solid and dimensional—slice into it from any angle and you would find the same stuff, the same rich meat. My sorrow, which amazed me scarcely less at the time than my dream, may have been my intuition, as yet inarticulable, of the chasm opening up between that meaty seamlessness and the ghostly discontinuity, luminous fragments with dead air like test pattern static between them, that life would soon become and must already have begun becoming. The dream was a cry for wholeness, for solid earth from one sinking into quicksand. It was a sumptuous film created to counter a dread of scissored frames.[[6]] I tried to summon a knowing cynicism, but when I thought of the dream I felt sick at heart. It faded only very slowly, leaving a residue of longing and bitterness that was acute for a time and fitful for a long time after that.

Curiously, I took less notice of Liesl after that. I had known–would know?–her somewhere else, but things were different here. As a notion that she was a figure from the future crept into me and took silent hold, her present self, a premonitory figment only, dissolved.

Over the next two years I sank, half deliberately, into a dreamy inwardness, a lush romanticism that kept an active gregariousness around it like a hard shell protecting a creamy yolk. Piano playing was the natural art form to express this. For years I had practiced my Conservatory lessons diligently, but now I poured myself into music, composing song after song. Having artistic “leanings” but no proper medium was a problem that had nagged me for a long time,{{7}}[[7]]Facility at mimicry and a persevering work ethic hid for a long time the nature of any individual talent I might possess, and despite my best efforts they still obscure this, especially when I am working too slowly. Working at top speed, for all the problems it causes, is a way of keeping my instincts out ahead of the various learned programs that stand ready to check and supplant them. Having abilities that were slightly above average in several areas made it difficult to find a true direction. Over and over, I found myself too proficient to give up, but not talented enough to gain real confidence. In a road hockey game, if twelve boys were available for teams, I would be picked fourth or fifth—too early to squelch hope and too late to firmly nourish it. Likewise, many expressed pleasure in my songs, a few marvelled at them; no one asked to hear them.[[7]] but I felt I’d solved it now. Visual arts had been my first love, but past the colouring stage, my utter lack of talent was prohibitive. With music I had at least manual dexterity, good rhythm, a so-so ear; I thought with the engine of a blinding work ethic I could whip these raw materials into something. I wrote sugary melodies over minor descending chords, often with an arpeggiated introduction that showed off my speed. My pride in them was only occasionally pricked by a suspicion that they resembled other songs; greater musicality would have recognized their progenitors instantly. When I presented one of these songs to my first girlfriend, inscribed in black pen on musical notepaper and played on an accompanying cassette, her birthdate its title, she was moved to tears. My adoration of her intensified, mingled with, inextricable from, a sense of my own omnipotence. Later, after playing it dozens of times to myself, I felt a bit disdainful of us both. Aside from the occasional oddity, such as a mournful and repetitive elegy for Charlotte Corday, my other kind of song was pure noise, waves of crashing discords, that I found particularly inspired and strangely relaxing. No one else enjoyed these, though, and, worse, some people thought I was joking when I played them. When the house was empty, I felt a strange exultation, a kind of energizing alarm, in sending my sugar pops and my clashing tumults billowing in alternating waves that finally cancelled out in exhaustion and a surfeited peace.{{8}}[[8]]The musical limitations that prevented me from recognizing my pop songs as derivative, and hearing that my noise was really just loud bad harmonies, were typified by a mistake I made in mathematics, sister of music. Mr. Brieve told us of the unsolved problem of trisecting an angle, a longstanding math conundrum with a prize offered for its solution. With two friends I worked all one heady night solving the problem. We had the solution ready on a side blackboard the next morning. Mr. Brieve, with a smile he quickly suppressed, pointed out that although we had done good work in trisecting the line we had drawn between the angle’s two rays, we had forgotten that an angle comprised, not a line, but the degrees in a circle’s arc. As the leader of the group, I was most embarrassed. I might be getting 98, but in mathematical terms I had just demonstrated a tin ear. Liesl, passing by on her way to her seat, smiled good-naturedly. Brilliant as she was, she was not even a snob.[[8]]

The conference room. (1978?) The murk parts and I see knees, in blue jeans, almost touching larger knees in brown cords. Fog slides, the hole widens.

Slowly, I raise my eyes. Silver sun buckle. Oh, oh. Big gut and chest, in blue checks. Now the face. A huge one, scowling. Walrus moustache, long blond shag. Oh, oh, oh.

38, he says. The name already past, I missed it. He’d been a steelworker, a millwright. Is now a doctor. A psychiatry resident. It is all barked out in a deep, almost-growl. In-my-face, like I bumped him in a prison yard. Do I understand?

I nod, careful to put nothing in my eyes. No matter how much danger I’ve kept time with, he is taking me further back, back to first recognitions. To straight power and the eagerness to use it.

Still–because he’s new?–I ask him about something I saw recently.

“Do you see a ghost now?” He grins, smoker’s teeth. Looks from side to side, puts big knuckly hands up beside his ears, wiggles his fingers. “Hello? Am I Caspar?”

The conference rooms are unbelievably tiny. No more than closets really. Two chairs, a quarter inch between the knees, and the walls right there. Smaller than the smallest elevator. Like a womb you share with another fetus for an hour. Who had thought of it? On occasion, with the right person, the intimacy can be thrilling. To Rose, whose perfume fills the space, I said it was like two soul-moths, the wings grazing. She blushed and said you could say that. More often it is tense, fraught. Both of you talk rapidly to fill the space. And then, not infrequently, there is this. Two animals sewn into a pirate’s sack. I zoom in on the ridges in his cords, the woebegone furrows between them.

“Give me more of that,” he growls, chin angled up.

More of what? We’d been sitting in silence, the soup curdling in. “Hello?” I hear, and throw myself further into it, wading into the tough talk like a surf that will wake or pulverize me. “What about–?” And I ask him about some events over the years, the ones I’d come to call transmissions. Though I don’t use that word with him.

“Ideas of reference,” he says.

Ideas of reverence,”{{9}}[[9]]A certain class of synchronized movements, more intense than coincidence, has for me the character of with a stronger and infinitely more accomplished partner. If you accept this stranger’s outstretched hand, and try to follow steps that are fleeter and more subtle than any you know, you may find yourself swept into a ballroom of opulence, where you catch glimpses of jewels and finery, fantastic faces, that you can hardly believe exist outside of dream. Following such a lead means the utmost pliability and quickness of response within yourself: it is the willingness to be led, the eager abandonment to command that lends to feet so ardent to mimic grace, grace itself. The dance lasts a second—an eternity. It is only when you find yourself again, breathless, in the seat you once occupied, that you perceive the last wonder of the dance: it took up no span of your life and yet occurred within it; it spun you nowhere yet you are not where you were. A number of such paradoxes are folded tight inside one marvel, which you will carry like a locket at the centre of yourself, the astonishment and rippling curiosity of having danced with Time. Often the first chord of the music, the unknown hand stretched toward your table, resembles mere coincidence. Indeed, if it is regarded as such for more than an instant, the perfumed hand vanishes. Ardency is the first requirement in a partner.[[9]] I murmur. Clearly enough that I hear the difference, but not loudly enough for him to catch it. Echolalia and Perseveration are words that appear often in my chart. Pat, a fat nurse who likes to start things, showed me one night.

Now he’s standing, his ass in my face. A juicy fart would be the perfect ending. He turns the doorknob, lets it roll back. Turns. His crotch at my eye, baggy brown pleats. I do a zoom and walk awhile in the furrows, turned earth, up and down. I look up. Moustache ends hanging out of red, hair, ceiling. Sometimes the goop clears when I least want it to.

He gives me a hateful look, a glare that promises he will make me a special project. And I think he must have followed through, because suddenly, very suddenly, like a rip of cold air, he is nowhere near me, ever. I see him standing down the hall, though not with his hands on his hips, not glowering. Not even looking up. As if he’d been yanked off me by someone very stern. Like someone just windmilling into someone on the ground, a teacher hauling him back by the shoulders. Rare, for all the bullying; the two people had to match exactly, like dancers. I don’t know what all might have happened between us.

__________

I answered a knock on the door. Summer, early fall, 2007—afterwards I told myself to write down the date but I forgot to. My hair was greasy, I hadn’t shaved or washed lately. It had been maybe a week since I’d left the apartment. “Good evening,” said an elderly, pleasant-faced man. He didn’t stare; no doubt he met all kinds, knocking on doors. A middle-aged woman stood beside and slightly behind him; she smiled politely. The man said he was from Elections Ontario. He had bright eyes magnifed by thick lenses, and was bald save for a monk’s fringe of short white hair. During my enumeration, he paused when I gave my birthdate: August 15 1955. He looked up from his clipboard with those large bright eyes, and extended his hand. “August 15 1929,” he said. We shook hands warmly.

I watched him walk down the hall with his younger lady companion. Feeling buoyed by the brief encounter, floating in it as in warm saltwater where I need barely move my limbs. I watched them almost to the elevator. They did not knock on any other doors.

I understood him to be an emissary, an angel calling me gently back to myself.

__________

On October 29, a song came into my head insistently. I hadn’t thought of it in years, but now I heard it constantly. It was a song from my early childhood. I heard my mother’s voice, clear and warm, but I couldn’t see her face, she must’ve been behind where I lay.

I had a little nut tree,

Nothing would it bear

But a silver nutmeg,

And a golden pear;

The King of Spain’s daughter

Came to visit me,

And all for the sake

Of my little nut tree.

I wrote down the words–the voice stopped singing then–and pinned them to the black foam board that covers a third of one wall of this room, from near the floor to above my head. The area involved is about 30 square feet. The notes on the transmissions since April covered the black completely, layers deep in places. I had to push the pin hard to make the new one stick. Looking at the mass of cards and pages and Post-Its and magazine photos and newspaper clippings, I felt a mixture of security and mild dread. Like someone who has filled his pantry and fridge with groceries but knows that at some point it will all have to be cooked. It will be big, I thought. Long. It wasn’t so much the number of transmissions as it was the gaps between them. What about that? I wondered. Imagine a flurry of telegrams about an event and an equal number of messages from someone who writes you at long intervals. Which would be harder to describe: the event or the relationship?

I punched “I had a little nut tree” into Google and saw a black-and-white picture of Catherine of Aragon, one of those northern Renaissance portraits I find so frustrating and moving. Their blend of awkwardness and sophistication, as if talent is coming into focus randomly, is what you find in paintings by gifted high school students, which convey an external likeness guilelessly, without any trace of a peculiar inner life. “The characters in the nursery rhyme,” I read, “are believed to refer to the visit of the Royal House of Spain to King Henry VII’s English court in 1506. ‘The King of Spain’s daughter’ could be either Princess Juana or her sister Catherine of Aragon, daughters of King Ferdinand and Queen Isabella. The princess in the nursery rhyme was probably Catherine who was betrothed to Prince Arthur, heir to the English throne. Arthur died and Catherine married his younger brother, King Henry VIII. The first of Henry’s six wives, she was discarded by the King to make way for Anne Boleyn, whom the common English people called ‘The Great Whore’.”

The song had a second verse I hadn’t known. My mom had never sung it.

Her dress was made of crimson,

Jet black was her hair,

She asked me for my nut tree

And my golden pear.

I said, “So fair a princess

Never did I see,

I’ll give you all the fruit

From my little nut tree.”

__________

On November 2, I parked my car on the west side of the grounds of the former Hamilton Psychiatric Hospital. The buildings are being converted to office space for other social services. The work is proceeding from east to west, and the old brick buildings I parked beside, some of the original asylum buildings, are mostly deserted. I seldom run into anyone apart from an occasional dog-walker as I roam the wide grassy grounds. I strolled with my digital camera, looking for the right kind of tree, in sunlight, with dirt around its base. It was mid-afternoon and I kept glancing up at the sun. Waning as autumn advanced, the light was hardly ideal for taking pictures, but I felt myself slowing down, and before the solstice shut-down, which I knew would come early this year, I wanted to shoot some versions of the marks Paul Tamburlaine had made, which had been in my mind every day since April. I found a stick to make my marks, and I found two trees in different areas. A pine tree, with low bushy branches, in moist soil thick with fallen needles. And a maple tree, with no lower branches, in a circle of pale, cracked dirt. Neither was ideal but each had features I liked.

The shut-down started soon after, and went remarkably fast. Inside of a few days I could only read magazines, short articles with pictures, and soon after that nothing at all. I couldn’t follow the words with my eyes let alone understand them. If I got to the end of a sentence and tried it again, it was as if I was encountering it for the first time. Wisps of meaning clung around some words, but then dissolved into jots and squiggles. I stopped trying to read. Took as much time off work as I could. It is so much like that scene in 2001 when HAL’s circuits are pulled one by one. One function less as Dave Bowman moves along the row. The process might be even more radical now, the ruptures in functioning more extreme. All that’s really changed in thirty-five years is my reaction to it. I fight it less. It’s a small, huge change. Still I panic and flail sometimes, lashing out like a disturbed sleeper, especially if I’m asked, or ask myself, to think decisively. (And in those instants of flailing I see how easily, without this modicum of understanding, the panic could transmute to pathology, to diagnosis and treatment, to catatonia or worse.) The best I can manage is to let go and allow myself to sink into this gray, weighted dream, like one of those divers being lowered into the dark, their senses sheathed, looking so cumbersomely languid as they take their slow-motion walks, tottering in dark fluid, giant babies on the ocean floor.

It lasts about six weeks. Thoughts of suicide come and go. I try to watch them calmly–these particularly dark, jagged-edged clouds–and remember that they have passed before. The amnesia is still almost total. But that almost is a giant gain. Dimly I remember that I have been here before. Entered and left. I remember that there was another side, without remembering what it was. I keep the space I wait inside small, tiny as I can. Drinking (too much, which is the enough I need), watching movies I have seen before. The Sopranos are a godsend, 86 hours I can visit and leave at will. The car with music is also good, this womb-corpuscle filled with The Clash, “Spanish Bombs” on Repeat, down Duplex to Chaplin Crescent, travelling slowly up the bloodstream of Avenue Road, very late or very early (they are the same), when no one else, or only the occasional other, is awake.

__________

One reliable source of comedy is to tell people exactly what you remember. True, it can cause suspicion among people not accustomed to considering single frames slashed from a narrative. It’s not something they permit in themselves (or which, by now, is perhaps even possible), and their eyes imply you are holding out on them: You went to Paris and you remember a Coke? An orange table? But for others–sometimes easy to spot, sometimes found by surprise–there is, after a bewildered look, a bark of laughter, which sounds like pure relief, when they find that the main feature has been cancelled, something has overexposed or underexposed all that lavishly mounted celluloid, the projector’s defective lamp has burned it white or left it black, and so you chat in the empty theatre lobby, the scheduled entertainment replaced by a wall sconce casting a muted oval, or the serial number plate of the popcorn machine and a corner of last month’s poster pinned by a staple.

Even so. I’m haunted by the suspicion that I’m only trying to make a virtue of necessity. Don’t most people remember their lives? It’s not a question of elapsed time. My memories of my first trip to Europe, in autumn 1975, were no more abundant or coherent–I don’t remember more abundance or coherence–thirty years ago than they are today. If I stopped relating to people the fragments I recalled, it was because their reactions could no longer distract me from the question behind the fragments: Where was I during my trip to Europe? Was I by then sunk so far into dream that events vanished as soon as they happened, except for a few vivid flashes that jolted me awake and laid down durable traces? Or was it waking life that had become character-less, lacking an executive agent that would preserve tracks firmly? Depression is known to interfere with attention in numerous ways, including this one: perceptions reach the way-station of short-term memory but fail to be committed to long-term storage. Experience penetrates no further than the file clerk’s desk at the end of the day: Everything In Everything Out. Just these few I couldn’t find homes for, boss.

Except–isn’t there another possibility in that image? An overlooked one?

Can’t find a home; not, there is no home. Think of the difference. “Don’t look for a story in symptoms,” one caseworker said. But where else would you look? Piece it out. Over the years, you laugh along with everyone: Four months in Europe and that’s all there is? But maybe that’s all there was. If you keep remembering the same few things, isn’t that the opposite of random? Isn’t it possible that those snippets are what happened? Are at least stepping stones to story. Like the pebbles Hansel dropped when nobody was looking, the ones that lead through the dark forest home.

- The chess park. Germany. Green grass for the dark squares, the light ones sprayed white. The chessmen stand thigh-high, like milk cans with handles on top to move them. A platform at either end, steps up to it, the player lounging on a chair with armrests. Calling out moves. Men beside the board, smoking, drinking coffee or beer, lift the piece and walk it to its new square. Or carry it off the board. The taken pieces on either side huddle like interested dwarves. A game ends, a lifter takes the loser’s place. I think of Hackney and Moose. I am out in Paul Tamburlaine position, by a shade tree off one corner, watching.