Seiji Ozawa, left, and Haruki Murakami. Credit Nobuyoshi Araki (NY Times)

Seiji Ozawa, left, and Haruki Murakami. Credit Nobuyoshi Araki (NY Times)

Absolutely on Music is the kind of book that makes you want to go find the music for yourself… These conversations left me wanting more, in the best possible way. They made me want to go sit with a friend in the living room, listening to records, one after another, late into the evening. —Carolyn Ogburn

Absolute Music

Haruki Murakami & Seigi Ozawa

Knopf, 2016

352 pages; $27.95

“…all I want to say is that Mahler’s music looks hard at first sight, and it really is hard, but if you read it closely and deeply with feeling, it’s not such confusing and inscrutable music after all. It’s got all these layers piled one on top of another, and lots of different elements emerging at the same time, so in effect it sounds complicated.” —Seiji Ozawa, Absolutely on Music

.

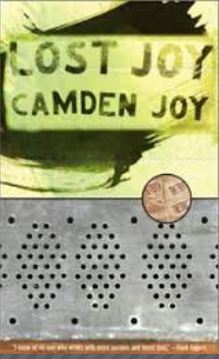

Absolutely on Music, by novelist and music aficionado Haruki Murakami and legendary conductor Seiji Ozawa (translated by Jay Rubin) is the best kind of eavesdropping. Although the book is (not inaccurately) described as series of “conversations,” the topic throughout is music, and the conversations appropriately become Murakami’s interviews of Ozawa regarding his long and storied career in the aftermath of diagnosis of esophageal cancer. Ozawa explains that “until my surgery, I was too busy making music every day to think about the past, but once I started remembering, I couldn’t stop, and the memories came back to me with a nostalgic urge. This was a new experience for me. Not all things connected with major surgery are bad. Thanks to Haruki, I was able to recall Maestro Karajan, Lenny, Carnegie Hall, the Manhattan Center, one after another…”

Murakami (b. 1949) is best known as a novelist, including Hard-Boiled Wonderland and the End of the World (1985) The Wind-Up Bird Chronicles (1994) and 1Q84 (2009-2010). He has received many awards for his work, including the Franz Kafka Prize and the Jerusalem Prize. He has published several collections of short stories and many works of nonfiction, including Underground, about the sarin gas attack on the Tokyo subway, and What I Talk About When I Talk About Running. Music often plays a strong role in Murakami’s writing. Scholars have long been drawn to exploring the musical worlds evoked in Murakami’s novels; they’ve created playlists and written dissertations (and created more playlists. There is even a special resource on Murakami’s website that provides references to the musicians, songs, and albums mentioned in his writing. The biography of Murakami written by his long-time translator, Jay Rubin, is titled Haruki Murakami and the Music of Words.

“How did I learn to write?” Murakami asks. “By listening to music. And what’s the most important thing in writing? It’s rhythm.”

Murakami’s and Ozawa’s daughters were friends, but the two artists only knew one another casually. They never spoke of their work to one another until Ozawa became ill with esophageal cancer in December, 2009. Because Ozawa had to limit his work, Murakami noted a new eagerness when they met to turn conversations to the topic of music, noting that it might have been the fact that he was not talking to a fellow musician that “set him at ease.” The task of publishing these conversations came from a story Ozawa told Murakami about Glenn Gould and Leonard Bernstein’s 1962 performance of Brahms’ First Piano Concerto. Murakami writes, “’What a shame it would be to let such a fascinating story just evaporate,’ I thought. ‘Somebody ought to record it and put it on paper.’ And, brazen as it may seem, the only ‘somebody’ that happened to cross my mind at the moment was me.”

Seiki Ozawa (b. 1935) began conducting as a boy in Japan when a rugby injury sprained his hand too badly for him to continue his piano studies. His skill soon brought him to the United States, where in 1960 he won first prize for student conducting at the Boston Symphony Orchestra’s Tanglewood festival. The young Ozawa studied conducting under legendary conductors such as Herbert von Karajan and Leonard Bernstein, who both figure prominently in these conversations. He went on to serve as the music director of the Boston Symphony Orchestra for 29 years, and as the principal conductor of the Vienna State Opera. He has received many honors and awards, including a Kennedy Center Honor and two Grammy Awards.

It’s interesting to note that the collection opens with a discussion of who is really in control during a performance of a concerto: the soloist or the orchestra’s conductor? Murakami initiates these interviews not with Ozawa’s own recordings, but with a discussion of Bernstein’s well-known disavowal of the interpretation of the Brahms First Piano Concerto as performed by Glenn Gould and the New York Philharmonic in 1964. Bernstein spoke to the audience prior to the performance, saying:

I cannot say I am in total agreement with Mr. Gould’s conception, and this raises the interesting question: “What am I doing conducting it?” [Audience murmurs, tittering.] I’m conducting it because Mr. Gould is so valid and serious an artist that I must take seriously anything he conceives in good faith, and his conception is interesting enough so that I feel you should hear it too.

Gould often performed with tempi so eccentric that it was difficult to regulate his interpretation together with that of the orchestra. It was this that prompted a discussion between Murakami and Ozawa as to which artist, conductor or soloist, was really in charge of a performance. But in this dialogue of two renowned artists, Seiji Ozawa and Haruki Murakami, who is in charge?

Though it is Ozawa’s history, the book ultimately belongs to Murakami. The comparison to Glenn Gould is an apt one, I feel, for Murakami’s prosody is, like Gould’s musical syntax, both engaging and strongly idiosyncratic. The language is unmistakably Murakami’s throughout. The syntax and rhythm of the words (at least as translated by long-time Murakami translator Jay Rubin) could be lifted straight from the page of any Murakami novel. I kept feeling as if a cat were gazing silently from the other room. If you are a fan of Murakami’s prose, then you will enjoy this book as well.

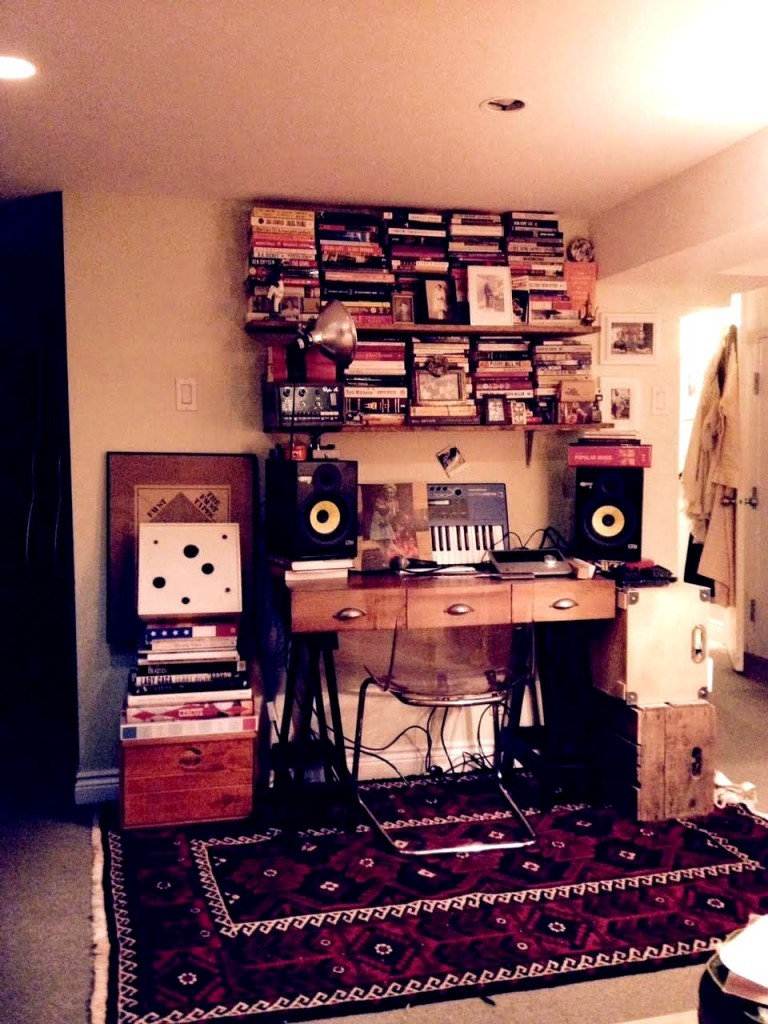

The conversational settings (the book consists of six conversations, separated by shorter “interludes”) are described only in the loosest terms. The first conversation, for example, takes place in Murakami’s home “in Kanagawa Prefecture, to the west of Tokyo.” Albums and CDs are pulled off the shelf to play as they talk, but the shelves themselves are never described; it’s as if they are being pulled from thin air. There’s something of the animated drawing about these conversations, the way that the suggestion of a particular recording prompts an immediate search for music. In the example here, the search is immediate. Though we haven’t any idea where the two are seated (or if they are seated), no sense of the room, or the light, the time of day or night, the mention of Lalo’s piece for orchestra and solo violin initiates a small flurry of activity:

Ozawa: “We [the violinist Anne-Sophie Mutter and Ozawa] Lalo’s Spanish something-or-another. She was barely twenty years old at the time.

Murakami: Edouard Lalo’s Symphonie Espanole. I’m sure I’ve got a copy of that somewhere.

Rustling sounds as I hunt for the record, which finally turns up.

Ozawa: This is it! This is it! Wow, I haven’t seen this thing for years.

Here, too, you get a sense of the way in which Murakami, the first-person author, enters the page as himself rather than via the transcriptionist of his own words. He’s “Murakami” except when making “rustling sounds” as he searches for the record he has in mind, which “finally turns up.” Those details—unexplained rustling, the “finally turns up,” which insists on being read with a kind of drama whose merit is uncertain—is classic Murakami.

There’s no doubt, however, that Murakami knows his stuff. As Ozawa himself puts it in the book’s afterward, “I have lots of friends who love music, but Haruki takes it way beyond the bounds of sanity. Jazz, classics: he doesn’t just love music, he knows music.”

One of the most fascinating aspects of this dialogue comes through the two very different ways in which they’ve each come to know the music that they love. For Murakami, his knowledge of music comes through avid and detailed listening to recorded music, supplemented by live performances when possible. As he admits, “a piece of music and the material thing on which it was recorded often comprised an indivisible unit.”

Ozawa, on the other hand, is far less familiar with recorded works, even his own. His knowledge of music comes from his study of it. His first encounter with Mahler was through reading a score: “I had never heard them on records. I didn’t have the money to buy records then, and I didn’t even have a machine to play them on.” The music itself was revelatory, “a huge shock for me—until then I never even knew that music like that existed…I could feel the blood draining from my face. I had to order my own copies right then and there. After that, I started reading Mahler like crazy—the First, the Second, the Fifth.” The first time he ever heard Mahler performed was as Bernstein’s assistant at the New York Philharmonic. Because of the way in which he learned the repertoire, Ozawa, unlike Murakami, was less familiar with the range of recorded performances of any given piece. Murakami is struck by what he calls “the fundamental difference that separates the way we understand music.” He finds that difference between a music-maker and a music lover to be an almost-literal wall, “especially high and thick when that music maker is a world class professional. But still, that doesn’t have to hamper our ability to have an honest, direct conversation. At least, that’s how I feel about it, because music is a thing of such breadth and generosity.”

The first conversation revolves around a variety of recordings of Beethoven’s Third Piano Concerto. A 1957 performance with Glenn Gould and the Berlin Philharmonic under the baton of Herbert von Karajan is compared with Gould’s recording with Leonard Bernstein and the Columbia Symphony Orchestra (composed of members of the NY Philharmonic) in 1959. The two then listen to Rudolf Serkin’s recording of the same concerto with Bernstein in 1964, which is taken at such a rapid tempo that Ozawa exclaims in astonishment, “It’s kind of an inconceivable performance.” They listen to another recording on period instruments, or the actual instruments for which Beethoven would have been writing: Jos van Immerseel performing on the fortepiano, rather than the modern-day piano, for instance. (Oddly, neither the orchestra nor the conductor is named.) This performance provokes the kind of observation that will delight the serious student of music, or anyone who enjoys thinking about sound: Ozawa says, almost as an aside, that in this period-instrument recording that “you can’t hear the consonants.”

Ozawa: The leading edge of each sound.

Murakami: I still don’t get it.

Ozawa: Hmm, how can I put it? If you sing a-a-a, it’s all vowel. But if you add consonants to each of the a’s, you get something like ta-ka-ka, or ha-sa-sa. It’s a question of which consonants you add. It’s easy enough to make the first ta or ha, but the hard part is what follows. If it’s all consonant—ta-t-t—the melody falls apart. But the expression of the notes changes depending on whether you go ta-raa-raa or ta-waa-waa. To have a good musical ear means having control over the consonants and the vowels. When the instruments of this orchestra talk to each other, the consonants don’t come out.

Murakami next brings out the 1982 recording of the piece with Rudolph Serkin again at the piano, and Ozawa himself conducting the Boston Symphony Orchestra. Here, we’re privy to Ozawa’s self-critique—“Now, this is ‘direction.’ Hear those four notes? Tahn-tahn-tahn-tahn….I should have done more of that.”—and his suggestion that Serkin, who was now late in life, realized that it was probably “his last performance of this piece, that he won’t have another chance to record it while he’s alive, and so he’s going to play it the way he wants to. Period.”

Finally, they listen to Mitsuko Uchida’s 1994 recording with the Royal Concertgebouw Orchestra under the baton of Kurt Sanderling. Earlier, the two have discussed the use of silence (the Japanese use the word ma to describe this quality) and the way in which Gould uses ma so naturally in his interpretation. Now they find a similar quality in Uchida’s playing, the silent intervals, her “free spacing of the notes.”

Beethoven: Piano Concerto No.3 / Mitsuko Uchida, Seiji Ozawa. Saito Kinen Orchestra

This concept of ma comes back as Ozawa describes to Murakami the conductor’s role in bringing the orchestra in following a break in the sound:

Murakami: When you’ve got an empty moment and you have to glide into it, the musicians all watch the conductor, I suppose?

Ozawa: That’s right. I’m the one responsible for putting it all together in the end, so they’re all looking at me. In that passage we just heard, the piano goes tee…and then there’s an empty space [ma] and the orchestra glides in, right? It makes a huge difference whether you play tee-yataa or tee…yataa. Or there are some people who add expression by coming in without a break: teeyantee. So if you do it by kind of “sneaking in” as they say in English, the way we heard, it can go wrong. It’s tremendously difficult to make the orchestra all breathe together at exactly the same point. You have all these different instruments in different positions on the stage, so each of them hears the piano differently, and that tends to throw off the breath of each player by a little. So to avoid that kind of slip-up, the conductor should come in with a big expression on his face like this—teeyantee.

Murakami: So you indicate the empty interval [ma] with your face and body language.

Ozawa: Right, right. You show with your face and the movement of your hands whether they should take a long breath or a short breath. That little bit makes a big difference….it’s not so much a matter of calculation as it is the conductor’s coming to understand, through experience, how to breathe.

Each conversation focuses very loosely on a topic, but the strength of this book is found in its soaring, tangential details. The second conversation revolves around Ozawa’s performances of the Four Brahms Symphonies with the Boston Symphony Orchestra, the manner of organization within orchestral groups today, particulars of instrumentation in the horn section of Brahms’ First Symphony; Brahms evokes Ozawa’s mentor, Hideo Saito. Ozawa’s Saito Kinen Orchestra was formed to mark the 10th anniversary of the great conductor’s death. The third conversation revolves around Ozawa’s experiences during the 1960s as he moves from New York Philharmonic, where he was assistant to Leonard Bernstein, to working with the Chicago Symphony, to three recordings Ozawa made with the Toronto Symphony of Berlioz’ Symphonie Fantastique.

Seiji Ozawa conducts Berlioz: Symphonie Fantastique, Toronto Symphony Orchestra 1967. 1st Movement: Rêveries – Passions.

In the fourth conversation, the two discuss the works of Gustav Mahler, a composer who’s work wasn’t widely performed until Leonard Bernstein championed his works in the 1960s. Of course, Murakami explains, one of the reasons Mahler wasn’t performed was that his work, like the works of all Jews, was “quite literally wiped out over the twelve long years following 1933, when the Nazis took power, to the end of the war in 1945.”

This is a fascinating dissection of both the composition and orchestration of Mahler’s nine symphonies and a history of the performance styles that were used over the decades that Ozawa has been conducting them. The emerging prevalence of recordings actually changed the performance styles; as recording moved away from recording the overall sound, focusing instead on individual instruments, so too did the tendency of orchestras to aim for a more transparent, detailed performance. The whole chapter on Mahler is one of the richest in the book. Yet, here’s Murakami, breaking in again to note Ozawa “eats a piece of fruit.”

Ozawa: Mmm, this is good. Mango?

Murakami: No, it’s a papaya.

Other times, Murakami’s interruptions are to provide poetic interpretation that comes in surprising passages, however lovely his descriptions may be. For example, while listening to the third movement of Mahler’s First Symphony, Murakami notes that “the clarinet adds an indefinably mysterious touch to the melody, the strange tones of a bird crying out a prophecy deep in the forest.” The line here, not unlike the mysterious touch of the clarinet, is surprising only because it is so rare; it’s a language from another time. In this book, the magic comes from two skilled craftsmen talking about their work with curiosity and affection.

The fifth conversation revolves around Ozawa’s experiences conducting opera, both staged and in concert performances. He recalls being “booed in Milan” at La Scala. Murakami presses him, asking twice, “Do you think there was some resistance to the idea of an Asian conducting Italian opera at La Scala?”

Osawa replies, “The sound I gave Tosca was not the Tosca they were used to.”

“Back then, weren’t you the only Asian conducting at a first-class European opera house?”

“Yes,” says Ozawa. “I suppose I was.”

That the two men are both Japanese, conversing in Japanese, is an issue that glides just below the surface of the conversation. Many times, Ozawa credits his lack of English fluency to explain why he simply didn’t notice the political waters in which he swam as a young conductor in New York and Europe. When he recalls the days in which Ravinia, the prestigious music festival outside of Chicago, was an all-white establishment (in the context of bringing Louis Armstrong to the festival), neither acknowledge that his very presence contradicts the memory of “all white”.

The final conversation centers on the Seiji Ozawa International Academy Switzerland. It’s a summer chamber music program that works with promising young musicians in small ensembles and extraordinary master instructors such as violinist Pamela Frank, cellist Sadao Harada, violist Nobuku Imai, and violinist Robert Mann. It’s a program designed around the very principles Ozawa learned from his first teacher, Hideo Saito.

Reading Conversations on the subway, or a cafeteria, or a picnic table in the late autumn sun, I could usually call to mind some of the music under discussion from memory, down to the scratchy sound of cracks in the vinyl, the thick humidity of the needle tracing silence between movements, as if it were playing just a the limit of earshot. But when I sat down to write about the book, I felt compelled to search out the actual recordings. I found many of them on Murakami’s website, which (as I mentioned earlier) contains playlists of works referenced in his other books. Other pieces, though not all, can be found online. These conversations left me wanting more, in the best possible way. They made me want to go sit with a friend in the living room, listening to records, one after another, late into the evening.

—Carolyn Ogburn

Carolyn Ogburn lives in the mountains of Western North Carolina where she takes on a variety of worldly topics from the quiet comfort of her porch. She’s a contributing writer for Numero Cinq and blogs for Ploughshares. A graduate of Oberlin Conservatory, UNC-Asheville, and UNC School of the Arts, she recently finished her MFA at Vermont College of Fine Arts and is currently seeking representation for her first novel.