.

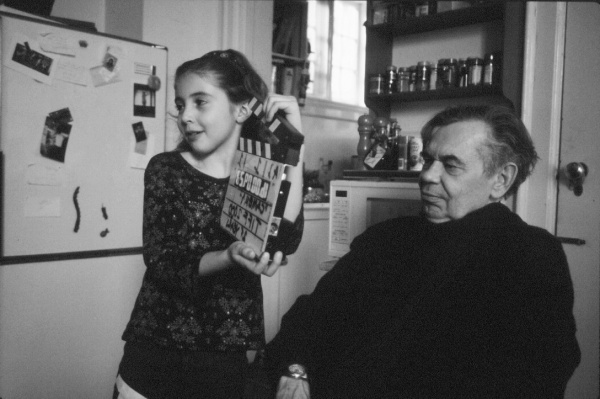

In Canadian director David Cronenberg’s short film “Camera,” an elderly, retired actor speaks of his fear and malevolence towards an old film camera that a group of children bring into his home. The children assemble into a film crew, each with their own specific roles, and carefully prep the camera as the actor rages on about his career, death, disease, and memory, knowing that the children are inevitability preparing his next close up.

The actor fears the camera because he identifies the device with death. He sees the lens as like his eyes, capturing experiences he will relive at the end of his life. Yet unlike memory, the camera fixes a moment in time and in a sense causes the death of the moment and experience. This makes the camera, recording the death of moments, a device that solidifies his mortality. He anticipates he will look back on his life replaying experiences and memories caught on camera and will enter a voyeuristic state, disconnecting from his own perception and becoming a mere observer of himself, of his own life.

This identification with the old camera speaks to a central struggle for identity that Cronenberg circles in his work. He spoke of this, among other topics, in a recent interview celebrating his 70th birthday (which can be seen here and is well worth the 90 minute watch):

In the interview he was asked about identity in his 2002 film Spider:

We are all the creators of our own identities. Even if we feel that is something given, we are actively involved in creating our own selves. You wake up in the morning and it takes you awhile to become who you are. It’s not just that you have to have that coffee. You have to remember who you are, where you are, where you’ve been, were your dreams real, who you were in your dreams. You have to reconstruct yourself every day. And if for some reason you could not do that, because of something that happened in your brain or nervous system, I can understand that, I can feel that, I feel very close to that.

In “Camera,” the actor speaks of recorded moments and their longevity. He alludes to how, when he is dead or eventually loses his memory, these fragments of time will represent how he is remembered. The camera will become the constructor of his identity, his memory. Rather than being an accumulation of his thoughts, feelings, and what he has or has not done, he will be only what has been recorded or documented.

When the actor appears on the children’s camera in the final shot, we see him in a new, rejuvenated way. Though aesthetically beautiful, with its warmer colors, light music, and smooth inward zoom, this is quite a false image compared to what the more documentary camera eye has captured before the children’s film camera. If moments like this become all that is left of the actor, the camera will not only construct his identity, it will do so through a sepia lens, blurring the pores and flaws that might be the truth of who he is. If similar false images are all he leaves behind for others, and create their perceptions of him, then what becomes of his true self?

As the children’s camera slowly penetrates the actor’s privacy, his initial disdain for it disappears: what he initially sees as fearfully other, slowly becomes a part of him. Cronenberg’s work is fascinated with how what is other becomes part of the self. In Videodrome, we witness the protagonist, Max, become the type of violence he strives to air on his independent cable station. As he descends, his stomach morphs into a VCR-like wound, allowing others to control his actions by injecting him with videotapes. In The Fly, a scientist rushes his experiment and, using himself as a test subject, accidentally crosses his DNA with a fly, mutating his body in increasingly horrific ways. Crash involves characters who have fused their desire for violent car crashes with sexual pleasure, rending them unable to achieve one without the other. All these Cronenberg protagonists eventually come to embrace the other working against them. The violence and technology become a part of who they are, leading them into a spiral of self-destruction.

In “Camera,” the synthesis is more ambiguous, not entirely horrific. The camera invades the actor’s home and his resistance to the device gradually fades away. The camera and the actor synthesize their abilities to create something, an image, which without one another could not be whole. By the end of the short, the actor comes to associate, sympathize, and identify himself with the camera, comparing the two to an old couple aging alone together.

This old couple analogy draws attention to the children’s celluloid film camera as a technology, and as a technology with a mortality, too. There are two cameras in the film, the documentary digital camera and the children’s celluloid camera, the one he fears and is growing old like him. The camera that the actor directly addresses throughout most of the film captures a more digital or documentary style image, scrutinizing every inch and pore of his face in an unflattering and yet perhaps more suitable aesthetic for his cynical personality and perspective. In contrast, in the final shot the celluloid camera the children use has a more gentle and vibrant tone, creating a more nostalgic depiction of the old man as he reminisces about memories from long ago. This is the same man seen two ways and on this other level the film displays a debate between the old and the new technology.

Film is always on the brink of creating, discovering, and infusing new technologies but not without conflict at each stage of change. Rudolf Arnheim argued that the invention of sound recording would be the death of film. Filmmaker Peter Greenaway thought that home video, with the dreaded pause button, would destroy the experience of a film. Others believed that color would tarnish the significance of the story and actors. Recently though, there has been much debate over the proliferating use of digital film and the decline of celluloid, and “Camera” seems to reflect this.

Is this Cronenberg’s argument for the use of celluloid over digital film? To the disdain of many, in recent interviews,

Cronenberg has sided with digital film, arguing “it’s about time film died its natural death.” This stance may be a surprise to some, but Cronenberg has a track record of creating stories that expose some of the more honest and brutal truths about humanity and our obsession with technology. Perhaps he feels that digital film is more apt to capture this harsh and coarse nature. Or perhaps he enjoys viewing the cautionary themes within his work become a reality as the world swiftly embraces the newest technologies, without fully realizing their limits or implications, and leaving older forms behind in obsolescence. Film historians argue that we have lost nearly 80 – 90% of all silent films, most due to the deterioration of celluloid. In losing parts of our history we lose pieces of ourselves, and perhaps this is what Cronenberg is alluding to as the actor speaks of the camera causing irreparable damage to us all. Regardless, “Camera” contains an argument for both celluloid and digital, depicting the unique qualities of both and how the aesthetic of each can affect the tone of a story.

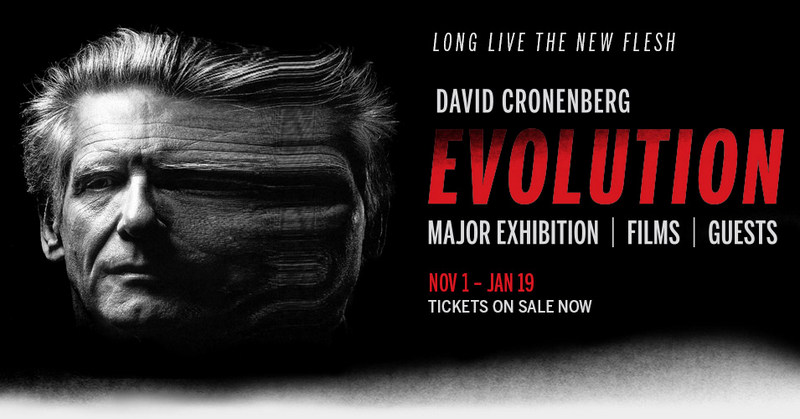

TIFF (Toronto International Film Festival) is currently hosting an art exhibition on David Cronenberg titled Evolution.

The exhibit is an accumulation of the filmmaker’s career, an eccentric collection of things Cronenberg that offer a close-up on the filmmaker much the same way the children’s camera in “Camera” offers a close-up. The exhibit continues until January 19th at the TIFF Bell Lightbox HSBC Gallery in Toronto.

–Jon Dewar

_______________

Jon Dewar is a grad student at University of New Brunswick, Fredericton and is working towards a degree in education. He is an avid film fan, interested in both film analysis and filmmaking. Some of his inspirations include directors such as Paul Thomas Anderson, Steve McQueen, and Martin Scorsese. Jon has written numerous screenplays and is working towards eventually producing some of these projects.

/

/

/