One morning I stood on a big round rock and put a heavy rock on my head. I was willing to be still, balanced on the rock and balancing the other rock on my head, but in order to keep it together I had to keep a very slight movement, a tiny dance, going on between the two rocks. That went on for many minutes. No one else was awake. —Simone Forti

/

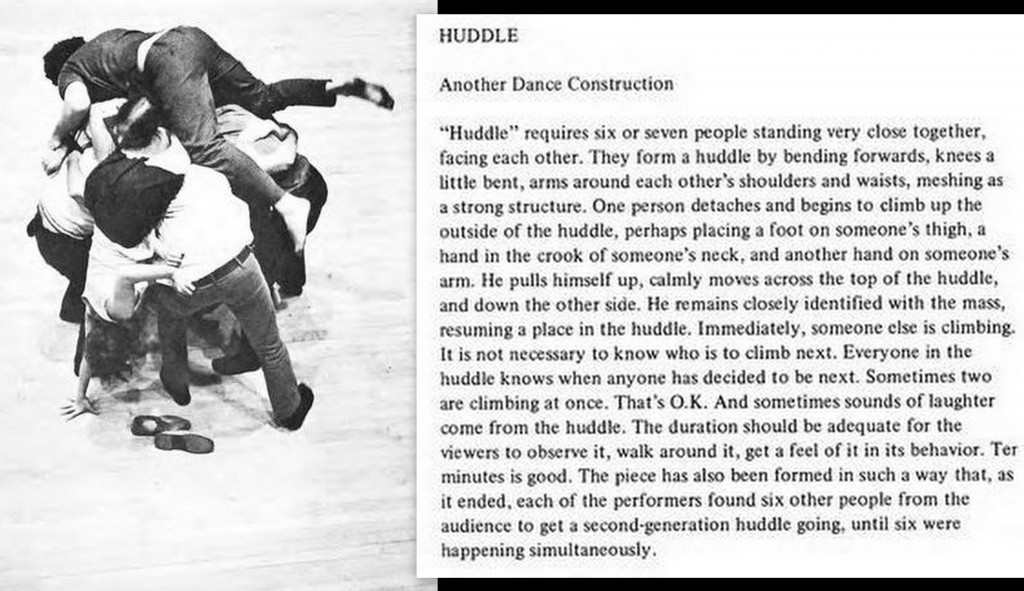

Huddle, Loeb Student Center, New York University (1969){{1}}[[1]]Photograph by Peter Moore, Score by Simone Forti (from Handbook in Motion, p.58-59)[[1]]

Huddle, Loeb Student Center, New York University (1969){{1}}[[1]]Photograph by Peter Moore, Score by Simone Forti (from Handbook in Motion, p.58-59)[[1]]

In the landscapes surrounding the hippy commune near Woodstock, New York where she briefly lived, Simone Forti spent a year of her twenties balancing on stone walls and observing the movements of the world. This is how she began becoming a legendary dance improviser, musician, creator of “Huddle”… In her 1974 classic Handbook in Motion (Contact Editions, 1998), Forti recounts:

One morning I stood on a big round rock and put a heavy rock on my head. I was willing to be still, balanced on the rock and balancing the other rock on my head, but in order to keep it together I had to keep a very slight movement, a tiny dance, going on between the two rocks. That went on for many minutes. No one else was awake.

By paying attention to minutia, Forti’s explorations tie up the essence of what a ‘big’ dance might also achieve, in a single, simple act. Something succinct enough to fit in a drawing, a photo frame./

This is a Dance: For Simone Forti

This is a Dance: For Simone Forti

Dance by Lucy M. May. Photo by Patrick Conan (2013)

Forti was my muse when I stopped in a national park in Croatia last year and asked my boyfriend to take a picture. I lay face down into the trunk of a tree that had grown out the side of a hill horizontally. Patrick tipped the camera to set me upright. “This is a dance,” I said to myself, as he clicked me into place.

§

In his book of essays on experimental choreography, Exhausting Dance: Performance and the Politics of Movement (Routledge, 2006), André Lepecki discusses a trend in dance criticism that laments any “down time” interrupting the constant flow of gestures in a dance. He cites New York Times Senior Dance Editor Anna Kisselgoff, who seems to feel that any stilling of motion threatens the very nature of dancing.

As a dancer, I embrace subtlety and especially stillness as integral to my work. Being still is not a “betrayal” of movement, as Lepecki theorizes. And a choreography that takes the form of a photograph therefore is not an oxymoron.

In Larry Lavender’s handout from the 2013 American College Dance Festival Association Conference, the admired scholar and professor defines the contemporary practice of choreography as “possibilizing the presence of people in places.” This necessarily vast definition suits the diversity of what is being made today in avant-garde dance, which includes as much idea as action, as much inactivity as activity, as much challenge and discomfort as pleasure and satisfaction for the viewer, as much happening off stage as upon it…

Lavender goes on to say that “Dance [capital D] is one of the approaches to choreography, and “a dance” is one of its possible outcomes.” So long as people’s bodies are inhabiting a space in time, a dance might be happening.

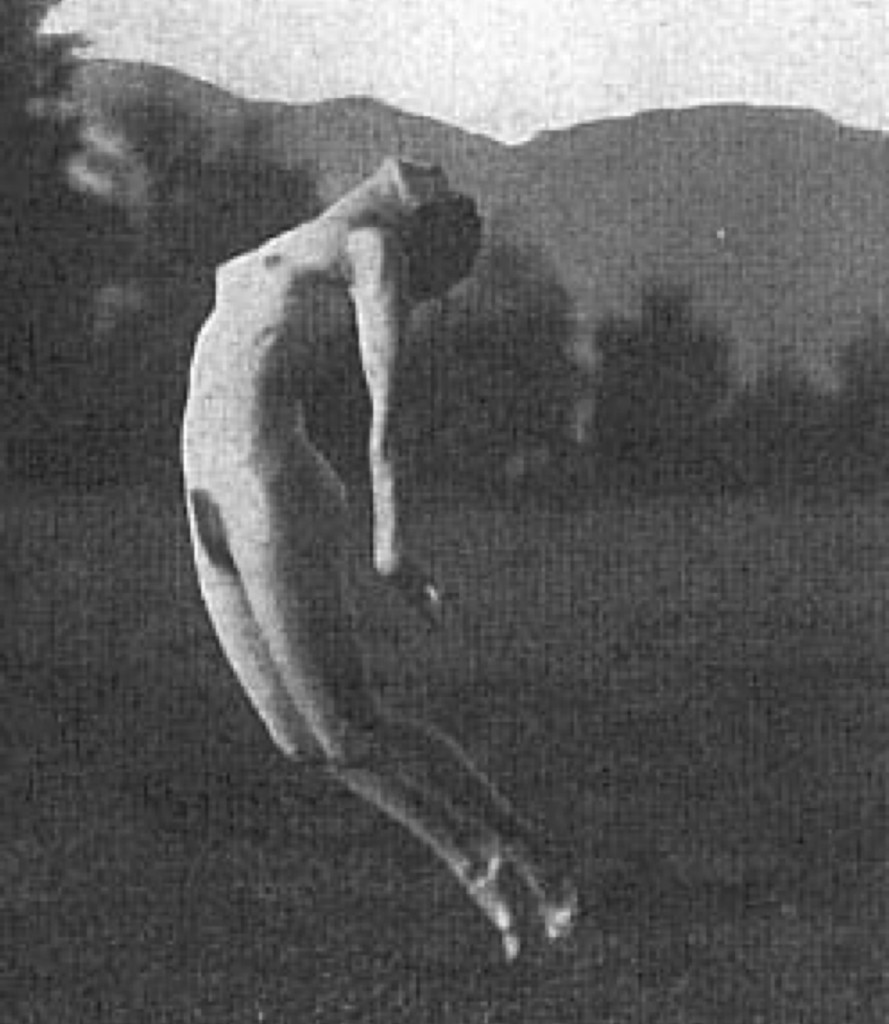

Gertrud Leistikow performing in a meadow near Ascona, 1914. {{2}}[[2]]Dance by Gertrud Leistikow (from Hans Brandenburg, Der moderne Tanz, 1921, reproduced in Empire of Ecstasy).[[2]]

Gertrud Leistikow performing in a meadow near Ascona, 1914. {{2}}[[2]]Dance by Gertrud Leistikow (from Hans Brandenburg, Der moderne Tanz, 1921, reproduced in Empire of Ecstasy).[[2]]

In Germany, both slightly before and after the First World War, dances were made for still photographs: figures caught in a landscape or an interior. The photographs circulated as part of an international culture of the body and movement. During that time, author Karl Eric Toepfer writes in Empire of Ecstasy : Nudity and Movement in German Body Culture, 1910-1935 (U. of California Press, 1997), that “dance was a cosmic force that was only partially visible in dance performances as such.” Toepfer cites dances imagined by writers Ernst Blass and Paul Van Ostaijen as well as approaches to dance that were about cosmic bodies and forces of nature in the multifaceted movement work of Rudolf Laban. “[W]hen dance assumes this sort of metaphorical identity,” he continues, “its meaning, its power to liberate, derives as much from its image and from ideas about it as from witnessing dance performances themselves.” Performers collaborated with photographers to hold the entirety of their dance inside a single cell of film back then.

§

While I was studying at The Rotterdam Dance Academy in Holland in 2006, dance artist and pedagogue Gabrielle Staiger taught me ways of using physical constraint to create meaning and emotion; following techniques developed by English choreographer Lloyd Newson and his DV8 Physical Theatre company. Just as Christian Bök limited himself to only one vowel for each chapter of his experimental poem Eunoia (Canongate, 2008), we spent afternoons dancing in pairs while limited to only one physical point of contact—back to back, hand-to-throat. We set out to discover what distillation of meanings might emerge from the physical relationships we restricted ourselves to. The results were often stunningly efficient and potent. Creation can be a game of closing oneself into a space in order to find surprising ways out, by driving the imagination to seek new possibilities.

Yvonne Rainer’s silent six-minute “Hand Movie” is a fine, danced example. From within the boundaries of a rectangle of celluloid, the renowned choreographer and film-maker (who emerged alongside Forti and the New York City cohort of the sixties and seventies) made her iconic film while confined to a hospital room. Her palm and fingers behave as surrogates for the body she could not use to dance.

§

The series of danced photographs included below is the product of a challenge I posed to choreographers from several places and time zones. I asked them all to create a dance, following Simone Forti’s inspiration, within the confines of a single photo frame.

Today’s dance makers ask us to pay attention to detail, to open our vision wider than the proscenium, to take in everything that is going on both outside and within our own bodies as spectators. If a dancer’s constant motion is stilled, if her movements are restrained or contained, something is not necessarily out of order—complexity can be uncovered in the simplest proposal if we look closely.

\

An Underground Dance by Dana Michel (Montreal).

Photo of Dana Michel, taken by Mathieu Léger (2014)

Photo of Dana Michel, taken by Mathieu Léger (2014)

The edges of the photo are littered with evidence of family: birthday card envelopes and balloons, the feet of an office chair and sofa, a baby blanket. At its centre, Michel is radial in a baby’s starfish posture.

Infants first learn to roll over by following others with their eyes. Michel gazes up towards her witness, pre-expressive, lips slightly parted—a sign of release. The comfort and familiarity of Michel’s outfit flow all the way to her curled fingers. She doesn’t reach for the edges of the space, but is only passively oriented in relationship to them. Her limbs kick out towards the skirting objects blindly, which gravitate like moons around her belly. All elements lay on the floor, ceding energy into the ground on a snowfield of spotless wall-to-wall carpeting.

Underground is a place of endings, stillness, recharging… As the winter solstice marks the pause between finality and new gestation, Michel’s dance in her parents’ basement could be one of winter energies, marking the drawn-out conclusion to her own childhood and her son’s infancy.

Michel writes:

photography jokes can fuel us for years. it’s a very lucrative energy source.

i wear all my old shit that i don’t care about when i’m at my parents’ place. it feels nice to be an asshole sometimes. my favourite thing in the world sometimes is to layer on asshole amounts of layers of clothing when i’m cold. i have bad circulation. and it’s cold as fuck in that basement.

the balloons in the background were leftover from my son’s first birthday party. balloons depress me post-celebration. they just won’t go away.

/

A Shape-Shifting Dance by Jacinte Armstrong (Halifax)

Photo and dance by Jacinte Armstrong (2014).

Photo and dance by Jacinte Armstrong (2014).

From her vantage point above the late spring earth, Armstrong’s movement plays out on an invisible Z axis. The spectator is invited into a game of peek-a-boo across the open space between her body and the ground. We step into Armstrong’s sandals, adopting her skin. Our shared shadow is a wraith interacting soundlessly, weightlessly with the landscape. It embraces a cluster of onion flowers that leap out of an armpit.

Armstrong’s dance is driven by the senses. Smell, taste and light sensitivity guide her towards the plant and into a sunlit tango with her double.

The onions are briefly entangled in a ring-around-the-rosie as they sense the light and shade pass over them. They might be adjusting their length and reach too, however slightly.

Armstrong writes:

The score was to feel the sensory/body experience of communing with the plants and wind, while asking the question “is this a dance?” with my eyes. Then the sun came out and revealed the outline of my body with the Alliums resting on and decorating my shoulder. It went away shortly after. Ephemeral. Then I ate one of the Alliums with a Daylily chaser.

/

A Dance of Entirety and Infinity by M. Eugenia Demeglio (Cornwall, United Kingdom)

Dance by M. Eugenia Demeglio.{{3}}[[3]]Digital photograph by K. Scott taken in a meadow near Helford Passage (2014).[[3]]

Dance by M. Eugenia Demeglio.{{3}}[[3]]Digital photograph by K. Scott taken in a meadow near Helford Passage (2014).[[3]]

Demeglio stands like a patient lightening rod in the centre of a sunny field. She is central, distinct, immovable yet human-sized: we relate to her.

Demeglio acts as an extra-sensory dowsing rod, connected to the sky, the earth and to herself in between. She seems to sense an inner mantra that streams through her body, into the earth below her bare feet and up into the cloudless blue sky above her pointed index. But she also seems to be listening for other human voices.

“Every movement,” Demeglio writes, “is the language through which new meanings can be collaboratively generated with those who witness. The process is transparent. Everything is inherently contextual.”

Demeglio is in a timeless state of consciousness although the sun circles temporally around her, using her body as a sun-dial. It must be late afternoon, but the dance has no beginning or end. I am reminded of performance artist superstar Marina Abramović’s idea behind her four-month-long sitting performance “The Artist is Present”: Abramović saw herself as a mountain to which people would come. She would not move. Demeglio has chosen to be a vector through which our language might pass forever, in the permanency of the photo.

/

An Everyday Dance by Justine Chambers (Vancouver)

Dance by Justine Chambers, Photo by Katie Ward (2014).

Dance by Justine Chambers, Photo by Katie Ward (2014).

Chambers’s dishwashing dance is caught in mid-stride. Her action is, of course, very familiar, but the frame of the photo catches attentiveness in the pinpoints of her black irises. She sees where she is going but is also anchored to where she has come from with strong shoulders and an open chest. The apex of the gesture is paused; the sweeping blur of her arm shows a honed pathway, made precise over time by repetition.

The softness of the camera focus, the primary colors of the scene—red, yellow, blue—bring an artlessness to the piece that invites a close-reading of details and a mindful contemplation of the moment.

Several performers and choreographers of 20th century New York post-modernism (Trisha Brown, Bruce Nauman, Lucinda Childs, Yvonne Rainer) focused on the meticulous repetition and accumulation of mundane actions to structure their work, alongside Philip Glass’s minimalist compositions and John Cage’s Zen Buddhist contributions to music. Their methodologies, motives, practices and modes of presentation have changed shape over time, but an ongoing interest in the beauty of dailyness and unspectacular events has held sway through several generations of dance-makers.

Chambers’s Family Dinner collaboration with the Task Force collectiveis “an immersive dining performance” for an equal number of performers and audience. It literally brings the practice of art-making around a dinner table, where the temporary “family” unpacks the choreography of actions surrounding the collective making and consuming of a meal.{{4}}[[4]]http://tenfifteenmaple.org[[4]]

/

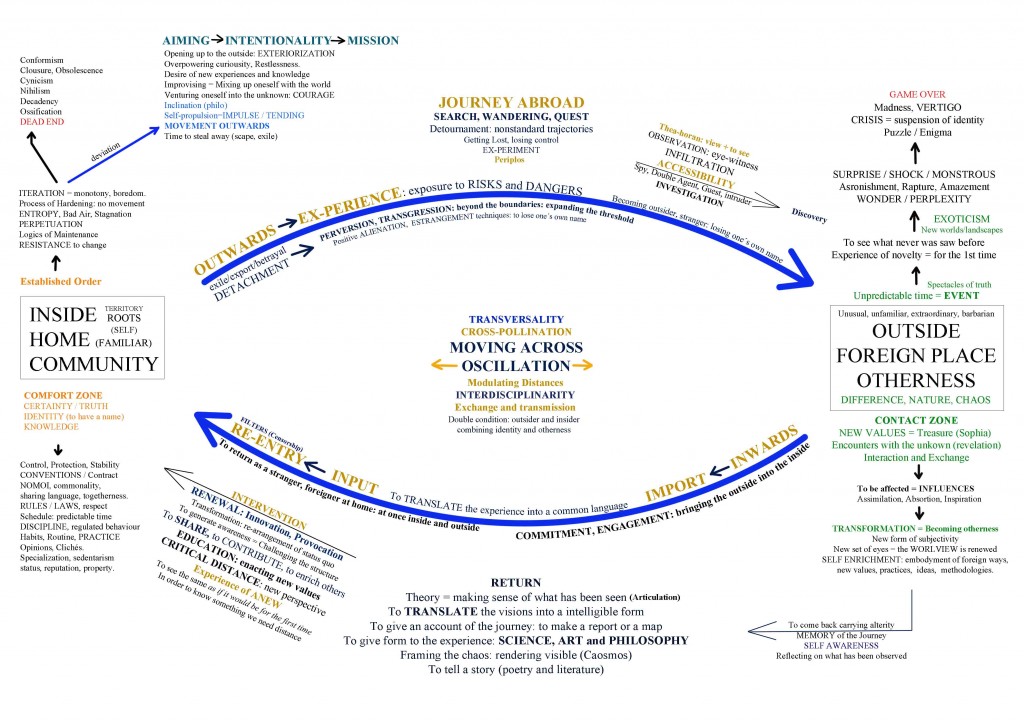

A Circulatory Dance by Diego Agulló (Berlin)

A Circulatory Dance by Diego Agulló (Berlin). Flow Chart by Diego Agulló (2013). Click on the image to view a larger version.

A Circulatory Dance by Diego Agulló (Berlin). Flow Chart by Diego Agulló (2013). Click on the image to view a larger version.

Agulló’s dance of concepts cycles clockwise. Branches snap off into corners. Its movement is directed by arrows that guide the eye and the mind around thickets of symbolic words. Agulló seems impelled by an inner restlessness to say what he knows. He engages us in a charged exchange of symbols across our synapses.

There is an effort to control the relative position of each element in the map. Words cling tightly to the sweep of the designed trajectories. Agulló sifts logic out of chaos but the position he holds balances precariously. The weight of the corpus of words seems to tremble against its structure, and the upheld posture might collapse if the movement stops—as Forti discovered in her rock-balancing micro-dance.

Conversion and translation are Agulló’s blood flow, necessary to the life of his dance. Its movement is propelled by a basic systole/diastole: the back-and-forth insistence of movement felt by all living things, in the human need for dialogue. It is endangered by the stasis of a short circuit.

Agulló writes:

Movement is a guarantee of preventing ossification. Ossification is the process of hardening that leads a system into stagnation and potentially into a dead end. […] translation is also a process of giving an intelligible form to what has no name. This can be considered the mission of art and philosophy.

How to learn to control the oscillatory movement? Perhaps the question should rather be: how to dance the oscillation? How to become the choreographer of your own life trajectory?

/

A Seeking Dance by Katie Ward (Montreal)

Dance by Katie Ward, Photo by Justine A. Chambers (2014)

Dance by Katie Ward, Photo by Justine A. Chambers (2014)

Ward’s face is turned away. Her whole spine bends towards the curve of the tree’s trunk. She and the tree share their ‘natural inclinations’ and arch in unison towards one another. We are granted privileged spectatorship of this intimate dance.

A tiny interstice remains between Ward’s left fingertips and the bark of the tree. In that inch, there seems to be a subtle exchange in progress. A garland of the chestnut’s leaves cascades down, contributing to the conversation. Her fingers are antennae that sense and impress upon the matter at hand.

“In my current work, via sophisticated and naïve surveying techniques,” Ward writes, “I explore properties of REALITY: matter, interconnection and imagination. I am inspired by my own intuitive leaps and imaginative versions of scientific explanations… I embark on explorative adventures, where the outcomes are unknown…”

Meanwhile, the man-made architecture of Ward’s sandals and the fence hidden in the greenery are left behind. In the moment of Ward’s intention towards her tall dance partner, straight lines and pre-fabricated structures are of little importance. All of Ward’s physical attention is thrust towards those few interceding millimetres between her body and that of the other. She trusts that something is there to be discovered.

—Lucy M. May

Choreographer Biographies

Spanish artist and self-described dilettante Diego Agulló lives in Berlin, researching the intersection between pedagogy and art. He creates contexts for learning and practicing theory across art and philosophy. He understands choreography as a practice of infiltration, which he applies through interdisciplinary work. His essay The Mischievous Mission intends to problematize the notion of professionalism in the arts.

Jacinte Armstrong is based in Halifax, NS and is newly the Artistic Director of Kinetic Studio, a Halifax-based organization that provides support to Nova Scotian dance artists, and presents a series of showings featuring artists from across the country. She is currently a co-founder and member of SiNS (Sometimes in Nova Scotia) dance collective, a dancer with Mocean Dance, as well as being her own man.

Justine A. Chambers is currently making and playing out of the Ten Fifteen Maple field house in Vancouver, a space she shares with four other artists situated in Hadden Park. She is a choreographer, dancer, teacher, facilitator and maker of things. Recently she has collaborated on the creation of works with Marilou Lemmens & Richard Ibghy, Brendan Fernandes, Jen Weih, battery opera, and Rebecca Bayer. She is one of four facilitator/mentors for the Vancouver Contemporary Art Gallery Youth Mentorship Program and was invited this spring to be a guest lecturer at Emily Carr University for Art and Design for the course The Act of Emotion.

M. Eugenia Demeglio is currently living and working in Cornwall, UK, where her practice includes movement and improvisation performances, installations, participatory events, videos, community projects and (body) sculptures. She is an Associate Lecturer in Dance Training at Falmouth University and also enjoys delivering improvisation workshops for non-dancers. “I like to think of myself as a strategist, creating frameworks for individuals to feel free within them.”

Dana Michel is a choreographer and performer based in Montreal, Canada. Her practice is rooted in exploring the disorderly multiplicity of identity using intuitive improvisation and image creation. She has been making and internationally touring work for the past nine years and her newest solo, Yellow Towel, premiered at the 2013 Festival TransAmériques in Montreal to critical acclaim. It was singled out as a remarkable production at American Realness Festival in 2014 by the New York Times.

Katie Ward is an independent choreographer dancer and most recently a teacher at Concordia University’s Dance department, who lives and works in Montreal. In 2008, along with Thea Patterson, Peter Trosztmer, and Audrée Juteau, Katie founded an artists group The Choreographers, who co-created and presented Man and Mouse and Oh! Canada. Her piece Rock Steady was presented in Lennoxville (QC), Créteil (FR), Maubeuge (FR), and Nottingham (UK) between 2010 and 2012. She presented her new solo The How and Why Machine in October 2013. A new group work, Infinity Doughnut, has creation residencies at Dance4 in Nottingham (UK) and in Créteil (FR), and is slated for performance in the fall of 2014.

Lucy M. May is a New Brunswick-born contemporary dancer based in Montreal. Her work—including choreography and performances in films and multimedia installations, site-specific creations, work alongside musicians, DJs, VJs, visual artists and archivists, and a dance with a horse—has been presented in Canada, Holland and Sweden. May has performed further abroad as a member of Compagnie Marie Chouinard since 2009. Her persistent desire to contribute to her communities has her presently experimenting with new movement training forms and writing frequently for the Canadian publication The Dance Current. She teaches as often as she can.