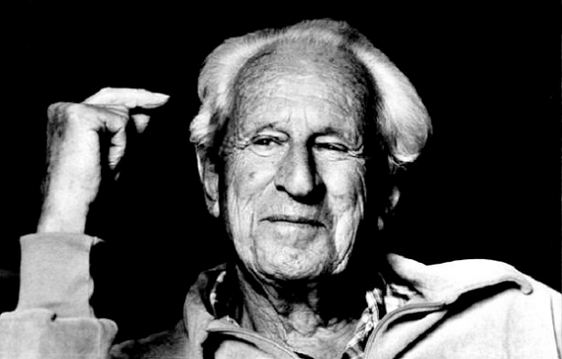

Numéro Cinq is honoured to publish here a wonderfully informal yet riveting and eminently astute (also frank and even funny — that orgasm/musk ox thing) interview with the poet and former Poet Laureate of the United States Donald Hall. The subect matter leaps from sexuality to ageing to metrics to ambition and old friends now gone — just what you might expect from an elderly but seriously ALIVE poet. Anne Loecher is a wonderful interviewer — she holds a poetry MFA from Vermont College of Fine Arts and lives not so far away, so she still drops in now and then at residencies which is always a delight. She also knows how to shape an interview, give it an emotional plot, a rare thing.

dg

On an early afternoon in early May I arrived at Eagle Pond Farm in Wilmot, New Hampshire to interview Donald Hall. Hall, born in 1928 in New Haven, Connecticut and raised in suburban Hamden, summers at Eagle Pond, home of his maternal grandparents and place of his mother’s upbringing. Eagle Pond operated as a farm for generations, up until his grandparents’ time. Rows of bright daffodils lined the driveway, planted there by Hall’s late wife, the poet Jane Kenyon, daffodils being among her favorites.

Hall published his first poem at age sixteen, graduated from Harvard in 1951 and earned a B. Litt. degree from the University of Oxford in 1953. He subsequently served fellowships at Stanford and Harvard, and in 1958 began his teaching career at the University of Michigan, where he met Kenyon, who was a student of his.

In 1975, Hall left his tenured position at Michigan with Kenyon so both could dedicate themselves to writing fulltime. After nearly twenty years together on the farm, Kenyon was diagnosed with leukemia, and died in 1995. Hall has remained at Eagle Pond since, continuing to write.

Across his writing career, Hall has published numerous books of poetry, prose, literary essays, sportswriting, and children’s fiction, and amassed a lengthy list of honors and awards including the Lamont Poetry Prize, the Edna St Vincent Millay Award, two Guggenheim Fellowships (1963–64, 1972–73), the Caldecott Award (1980), the Sarah Josepha Hale Award (1983), Poet Laureate of New Hampshire (1984-89), the Lenore Marshall Poetry Prize (1987), the National Book Critics Circle Award for Poetry (1988), the National Book Critics Circle Award (1989), the Los Angeles Times Book Prize in poetry (1989), and the Poetry Society of America’s Robert Frost Silver Medal (1990). He has been nominated for the National Book Award on three separate occasions (1956, 1979 and 1993), the Ruth Lilly Poetry Prize for lifetime achievement (1994) and appointed U.S. Library of Congress’ Poet Laureate (2006). Most recently, Hall was awarded the National Medal of Arts by President Barack Obama in 2010. Writing in a pre-interview email that he might tire out during our chat “If there is one thing I’m constantly aware of – it is that I am old!” – Hall was energetic and animated as we discussed the topics of posterity, reputation, and the conclusion of his poetry writing career.

—Anne Loecher

———

INT: I’ve been considering the careers of several poets who have drifted in and out of popularity. I wanted to ask you about posterity, obscurity, popularity, and how you feel about it with regard to your own work and reputation.

DH: I have seen so many people become famous, and disappear. If I live to be 300, I’ll see some of them come back. I mentioned Archie MacLeish, who was my teacher. I have doubt that Archie will come back, although he won three Pulitzers.

There were famous young poets when I was at college – Wilbur, Lowell and Roethke. Dick Wilbur is alive at 91, and in January he had a wonderful poem in The New Yorker.

I wrote Dick about the prosody of his poem. The second line has a caesura, after two syllables, the second after four syllables, then after six syllables, after eight syllables. I asked how many people would recognize that metric.

But, there’s William J. Smith, who is older than Dick and lives in the same town as Dick. Back around 1950, Smith was famous as a poet. I don’t think I’ve heard his name out loud since 1970.

Have you ever looked in the list of Pulitzer winners? I think they begin in 1932 or so. See how many names you recognize. There are many I don’t recognize, and you won’t recognize because of your youth.

INT: I’m not so youthful!

DH: Reputations go up and down.

INT: You’ve talked about The Back Chamber being your last collection of poetry. Did you know it would be, as you were writing it?

DH: Toward the end of the volume, the last two poems that I started for it both began in 2008. I did well over a hundred drafts, and I realized that this was the end. I felt it coming.

INT: The Back Chamber does not hold back from addressing sexuality, alongside ageing.

DH: Poetry is sex. And the engine of poetry is the mouth. Not the eye, not the ear. The ear and the eye are perfectly fine, but poetry originates in the mouth. Obviously the mouth is used in sex, beginning with the kiss.

The spirit that infuses me in reading a poet of beautiful sounds, like Keats, is sexual feeling. My poems had a lot of personal sexual feeling well into my seventies, but then I think the testosterone diminished. I felt the horniness going away, for two or three years. I rubbed testosterone into my chest, and it came back for awhile. That’s when I worked on later poems. But the cream diminished in its powers so I stopped.

There was an early poem that Janey (Kenyon) always liked — “The Long River.” I wrote it when she was eight years old. It’s the first poem I ever wrote which began without any notion of where it was going to go.

The Long River

The musk ox smells

in his long head

my boat coming. When

I feel him there,

intent, heavy,

the oars make wings

in the white night,

and deep woods are close

on either side

where trees darken.

I rode past towns

in their black sleep

to come here. I passed

the northern grass

and cold mountains.

The musk ox moves

when the boat stops,

in hard thickets. Now

the wood is dark

with old pleasures.

It’s about orgasm. It’s not about a musk ox. But musk ox is there because it is “SK, KS”. Actually, there’s a kind of meter to this poem, which I’ve never used elsewhere. In English verse, you’re counting volume when you’re talking about stress, or you’re talking about greater volume. “Con-tent” is iambic, and “con-tent” is trochaic. But in English, rather than Greek verse, which the Latins learned to imitate, it was the length of the vowel, not the length of the syllable you counted. In this one, it’s – short, long, long, long/ short, short, long, long/ short, long, long, short, long/ and, short, long, short, long/ and then short, long, long short.

There are a few lines when it doesn’t really work. I first had “the musk ox in his long head” and I was captivated, and kept going. And toward the end, working on it, or even after I’d finished it, I figured out what it was about. People have not used a sexual word to describe it, but found it sensual.

INT: Was that the first experience you had of moving through a poem without knowing what it was really going to be about?

DH: When I wrote a poem in my early twenties, I had to know what I was writing about before I started. Stupid: one of the poems from that time came from a definite idea, and it’s there. What the poem’s really about is something I never understood for years. Five years after I wrote it, somebody wrote an article about me, and explained to me what I really meant. It’s called “The Sleeping Giant,” which is the name of a hill, near where I grew up in Connecticut. I had the thought, that if a little kid believed it really was a sleeping giant, it would be pretty scary. Then he’d grow up and know it wasn’t. It was a poem, I thought in my head, about illusion and reality.

The Sleeping Giant (A Hill, so Named, in Hamden, Connecticut)

The whole day long, under the walking sun

That poised an eye on me from its high floor,

Holding my toy beside the clapboard house

I looked for him, the summer I was four.

I was afraid the waking arm would break

From the loose earth and rub against his eyes

A fist of trees, and the whole country tremble

In the exultant labor of his rise;

Then he with giant steps in the small streets

Would stagger, cutting off the sky, to seize

The roofs from house and home because we had

Covered his shape with dirt and planted trees;

And then kneel down and rip with fingernails

A trench to pour the enemy Atlantic

Into our basin, and the water rush,

With the streets full and all the voices frantic.

That was the summer I expected him.

Later the high and watchful sun instead

Walked low behind the house, and school began,

And winter pulled a sheet over his head.

People reading the poem in the New Yorker liked it best among my poems. I was jealous for my other poems. Then someone wrote an essay, saying that I had written many poems about fathers and sons, but the best one was “The Sleeping Giant.” It had not occurred to me. It was classically Freudian. When you are a baby, an enormous figure stands over you, not handing you a breast. It’s scary because it’s big. When I read the essay, I was stunned, and I agreed. I hadn’t known what I was writing about. I think that the people who preferred it to other poems didn’t know what it was about any more than I did. It communicated. It’s mysterious, how you can communicate by images, to another person. You can’t do it on purpose.

But, on purpose, you can write something in which you don’t know what’s happening. You can always cross out and throw it away. But that part of poetry – the part where you write things down, that feel right, but you don’t know why they’re right – left me as I got older. I was about eighty. As I said, it’s testosterone. (I tell that to a lot of people, and they want to look away.

INT: I understand that. I write about loss, but I wonder, as I say that, what I would find within my poems if I looked more closely?

DH: A great deal of poetry is about loss, love and death. Death is loss. My poetry has been called elegiac. I can be praising the old farm life, but then something is gone. The praise is love, the elegy is less, in the same poem.

INT: Regarding the issue of posterity, again, in your new poem “Poetry and Ambition” from The Back Chamber there’s a line “…If no one will ever read him again, what the fuck?”’

DH: Nobody will ever know about future reputation. I began writing very young, with ambition. I certainly wanted to be a great poet. In my day, or my generation, there were so many of us. At Harvard, weirdly enough, I knew Adrienne Rich. We double dated. We got to be good friends, later, not at that time. Robert Bly, John Ashbery, Frank O’Hara, Kenneth Koch; I’m missing some. We had the notion – and I wrote of it in an essay called “Poetry and Ambition” – that there was no point in writing unless you were going to be a great poet. It took me some time before I realized that nobody ever knows how they will seem in the future.

Ambition begins when you want to publish a poem in a magazine. Well, I did that when I was sixteen. And then, you wish that you could be published in the New Yorker. Then, you want a book. Then you want a second book, then you want a selected poems. It could certainly all be called ‘careerism. It can also be called ambition, and an eagerness to get better.

My father was the elder son of a self-made man who went only through the fifth grade, and worked for ten cents an hour, then was successful with his dairy business. And my father, being the elder son, could never do anything right. He was beaten down his whole life, which was short. He could never do anything right, and he was discouraged.

My mother came from this place – New Hampshire, where I live. In rural places, women worked as many hours a day as men did. Good God, my grandmother made soap. She churned butter. There was Monday washing, Tuesday drying, Wednesday baking. And at night time – do you see there, in the middle of the ceiling? In every room, there are lights in the middle of the ceiling. Do you know why? There would be a table in the middle of the room, and a great, big kerosene lamp, and the whole family would be around it at night, the single source of light. My grandfather would read books, not good ones, but books. And as the women talked; they were darning socks, they were tatting, or knitting. They never stopped. That was the way people lived.

So my mother then moved in 1927 to the Connecticut suburbs, where women didn’t work. No married woman was allowed to work. She wanted to ‘pass’. Her New Hampshire accent stayed with her – she said ‘Coker Coler’. She wanted to be a suburban wife, like everybody else, she grew up the oldest sister of three girls. She was the oldest sister to the universe. She was full of ambition. None of it had anywhere to go. So it went to me.

I was an only child. She was ambitious for me, and always pushing. When I started sending poems to magazines at fourteen, they would come back with printed slips. My mother would say, “Oh, there’s a rejection today, Donnie,” That was the beginning of my career.

When my first book came out, it was reviewed everywhere, instantly, reviews that praised it. And it’s no good. There are two poems in that book, one called “My Son, My Executioner” and “The Sleeping Giant” which I told you about. After the first reviews of praise, there was a second wave, responding to the first wave, that tended to be negative. Some of the negative reviews were certainly right, and they had me walking up and down.

All through my life I have written and published poems which I thought were good and which turned out to be terrible. And it’s hard to believe why I thought they were good at all. Some have held up for me.

INT: Is it possible that it’s a matter of your tastes having changed?

DH: Oh, it’s also being dumb about your stuff! There was one time I remember sending poems to Alice Quinn, who was the editor at the New Yorker. I had one poem that I was afraid was no good, and I almost did not send it to her. I decided at the last minute – what did I know? It’s called “Affirmation.” She took it, and published it about a week later. And people all over the country wrote me about it and told me they’d cut it out and put in on their refrigerators, and so on.

INT: What do you think of that poem now?

DH: I was kind of shocked, and convinced that it must be some good. I think that there are two opinions about the ending of it. I thought that one direction was obvious. And then most people took it the opposite of what I thought I’d said. And so many people took it the opposite of what I thought, that I decided it must have been one of those occasions where I was writing with the wrong idea of what I was writing. It begins:

“To grow old is to lose everything.”

I don’t think I was seventy when I wrote that. I’m eighty-three! It’s funny to read. What did I know?

Affirmation

To grow old is to lose everything.

Aging, everybody knows it.

Even when we are young,

we glimpse it sometimes, and nod our heads

when a grandfather dies.

Then we row for years on the midsummer

pond, ignorant and content. But a marriage,

that began without harm, scatters

into debris on the shore,

and a friend from school drops

cold on a rocky strand.

If a new love carries us

past middle age, our wife will die

at her strongest and most beautiful.

New women come and go. All go.

The pretty lover who announces

that she is temporary

is temporary. The bold woman,

middle-aged against our old age,

sinks under an anxiety she cannot withstand.

Another friend of decades estranges himself

in words that pollute thirty years.

Let us stifle under mud at the pond’s edge

and affirm that it is fitting

and delicious to lose everything.

When I wrote it, I thought when I said, “it is fitting and delicious to lose everything” that my sarcasm was obvious, and that it was all in the one direction, of a lamentation. And then I discovered that people took the word “affirm” as a positive, the reversal of what I thought I had said.

INT: That’s how I understood it. I didn’t understand it as sarcastic at all. So, if you can never know, does it also mean you can never know if your poem is good?

DH: I guess I’m saying so. A friend to wrote me about it, believing “affirmation” as positive, and telling me I was all wrong, I was sentimental, to be affirmative, because really, only the negative was true. That’s really what I thought I was writing, and that’s why I thought it wasn’t good. Who knows?

INT: You make some pretty striking points about ageing in your recent essay “Out the Window.”

DH: In almost any poem that I care for, there has to be a contradiction. If there’s ‘north’ in the poem, there has to be ‘south’ in the poem, or it’s no good. Oppositions. This was a snowy winter, and I kept sitting in this chair, looking out at the birds. I was writing about looking, thinking ahead to spring and the flowers, and it was all very lyrical. I thought: this essay doesn’t have any counter-motion in it, any north to go with its south. Then I went to Washington, and that fucker said, “Did we have a nice din-din?” I’m so grateful to the idiot. It’s what I needed. That condescension is totally other than the pleasant lyricism of looking out the window. And I think it made the essay. People say – did you bop him? I didn’t get mad. I was grateful. To Linda he says “Did you have a good lunch?” and he leans down to me and says “Did we have a nice din-din?”

INT: Are you working on more essays now?

DH: I’m going to do a book of essays. I’ve got a wonderful one I’ve just finished, I think, which is about smoking, when everybody quit. Playboy bought it.

The first essay in the book will be “Out the Window” which was all about being old. The others all will include aging. There’s another one I’m trying to write about poetry readings, where I find it hard to climb up to the stage. I have to sit down when I read now.

INT: When I was driving up here, I noticed the stone fence, and the cemetery down the road. So beautiful. Are there any family members buried there?

DH: No. It is beautiful, this is Wilmot. That graveyard was the beginning of East Wilmot. They were going to build a church – I think it was Methodist – and they started their graveyard before they had built the church. But New Hampshire shrunk. The population was at its greatest about 1855. It went way down, and it’s up again, but it’s all southern commuters to Boston. Early, it was single farms, every quarter of a mile, and pasture land up the mountain. The population dwindled, and East Wilmot never happened. About a mile farther down, there’s another graveyard, and on the right, there’s another church, the South Danbury church. In the South Danbury graveyard, I have a great grandfather and great grandmother. He fought in the Civil War and died in 1927.

When Jane and I were first here, we loved our place so much that we knew we’d stay here forever and that’s why we bought a graveyard plot. It was a positive, not a negative – love and death, this is where we’ll be. She died right in there (motioning to the back bedroom), and I will die in the same bed. My kids and doctor know that.

Five miles the other way, there is another old cemetery right next to the road, where I have great-great-greats. A little farther there’s a big cemetery, begun early in the nineteenth century, holding my great grandparents as well as Jane. There’s Jane Kenyon, 1947 – 1995, and then Donald Hall, 1928 – _, in a plot at the edge of the cemetery with the great trees above it.

———————–

Anne Loecher is a former Creative Director and copywriter who fled Madison Avenue advertising to work in non-profit communications. Having recently completed her MFA in poetry from Vermont College of Fine Arts, she is currently revising her poetry manuscript and writing her first screenplay. She lives in Maple Corner, Vermont (yes, that’s really the name of the town) with her husband, teenage daughter, her OCD beagle and ADD cat.