.

Eleni Sikelianos is the author of several books of poetry (one of them a book-long single ode titled The California Poem) and two hybrid essay/memoirs (The Book of Jon and You Animal Machine); she has translated work by Greek, Russian, Chinese, and French poets. She received her MFA from the Naropa Institute in 1991 and currently teaches at the University of Denver, where she is the director of the creative writing program.

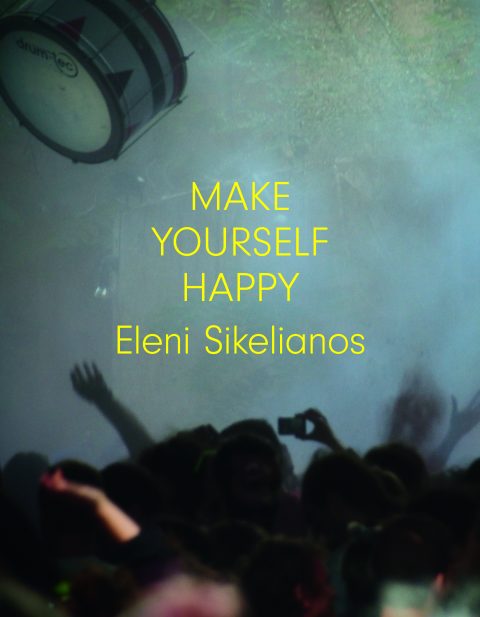

Ms. Sikelianos generously agreed to answer some interview questions from our reviewer, Julie Larios; the poet’s responses can be read in conjunction with our review of her new book, a collection of poems titled Make Yourself Happy.

Julie Larios (JL): Can you tell our readers a bit about Naropa University and your MFA studies within the Jack Kerouac School of Disembodied Poetics? That one word—“disembodied”—is especially interesting. What does it mean to you in terms of your own work?

Eleni Sikelianos (ES): I went to Naropa in the late 80s and early 90s, and was lucky enough to study with or be around an incredibly range of writers and artists: Allen Ginsberg, William Burroughs, Kathy Acker, Amiri Baraka, David Hockney and Marianne Faithful are among the most well-known. But I had classes with Anne Waldman, Diane di Prima, Alice Notley, Bernadette Mayer, Susan Howe, and these all marked me in various ways. Perhaps one of the most important things I learned at Naropa — besides being exposed to groundbreaking, culture-changing work — was to think of the poet as a figure of engagement. Engagement can mean many things: working in at-risk communities, or studying Sanskrit, but it means doing your work in a serious way.

I think “disembodied” came in as a bit of a joke (I wasn’t around at the founding of the school in the 70s), since the writing school was named for a dead man, and there were lots of dead writers who were genii loci, inspirational figures. Language itself is disembodied, you could say, despite its relation to the body that sounds it or writes it or reads it. One of the things I strive for as a poet is to embody (thought, feeling, experience) in language — and that is one of the great experiments of poetry — the ongoing journey back and forth between embodiment and disembodiment that the medium of language necessitates.

JL: You’ve been called an “experimental” poet. What do you think of that designation and/or the whole idea of designations and categories when it comes to poets?

ES: I was on the radio last month, and the radio host introduced me as an “experimental poet” about fifty times. My graduate students who heard it wondered why he couldn’t just say “poet.” I’m not that interested in categories in this regard, although I do feel fiercely loyal to communities and very connected to lineages. “Experimental” is kind of a stand-in word for a number of things, one of which might be writing that creates meanings as it makes itself, rather than heading toward predetermined meaning. Just a quick look in the Merriam-Webster will tell you a lot:

Experiment

1 a : test, trial

make another experiment of his suspicion — William Shakespeare

b : a tentative procedure or policy

c : an operation or procedure carried out under controlled conditions in order

to discover an unknown effect or law, to test or establish a hypothesis, or to

illustrate a known law

2 obsolete : experience

So, a kind of writing that allows the tentative nature of the world into its proceedings, that admits that meaning and reality aren’t fixed and sets out to test them, to discover and to try (the root meaning of “experiment”). And that has a historical connection to experience (which might itself be becoming somewhat obsolete). If we define it thus, then, yes, it’s a good designation. And if it’s a way for people to understand an approach to writing and reading in a meaningful way, then I’m for it.

JL: Your work indicates an interest in science as well as language. Some people approach poetic investigation and scientific investigation as if they were diametrically opposed perspectives on—and responses to—the world we live in. Why do you think that is?

ES: Well, science is itself a language, a way of communicating things about our world. The word “experiment” serves us perfectly here. I think of both poetry and sciences as ways to test out and discover things about the world, about meaning and structures. I’m not sure most people do think of science and poetry as diametrically opposed, but if they do, it might be because of a cliché about poetry’s sole or primary function as affective. That is not to say that carrying emotion isn’t an important behavior of poetry, it’s just not the only one.

JL: Any recommendations for our readers of poets whose work you're inspired by or of writing in general that interests you and/or informs your own work?

ES: For Make Yourself Happy, I went back to some of the poets who have been important to me for a long time. I was thinking about the joy and bounce in Frank O’Hara’s Lunch Poems, about the devotion of Lorine Niedecker’s sequences, and the combination of astringency and delicate care in Reznikoff’s Testimony. Ed Dorn’s fresh encounter with genre (the Western) and experiment in Gunslinger was in my mind, too. Although these didn’t go into the writing of Make Yourself Happy, recent books I’ve been excited about are Simone White’s Of Being Dispersed, Fanny Howe’s The Needle’s Eye, Dolores Dorontes’ Style (translated by Jen Hofer), and my student Carolina Ebeid’s You Ask Me to Talk About the Interior. I just started Valerie Mejer Caso’s This Blue Novel, and am loving it.

—Eleni Sikelianos & Julie Larios

N5

Eleni Sikelianos is a poet, translator, memorist and professor of creative writing at the University of Denver. Her books include Make Yourself Happy, The Loving Detail of the Living and the Dead, Body Clock and many others.

Julie Larios is a Contributing Editor at Numéro Cinq. She is the recipient of an Academy of American Poets prize and a Pushcart Prize, and her work has been chosen twice for The Best American Poetry series.

N5