x

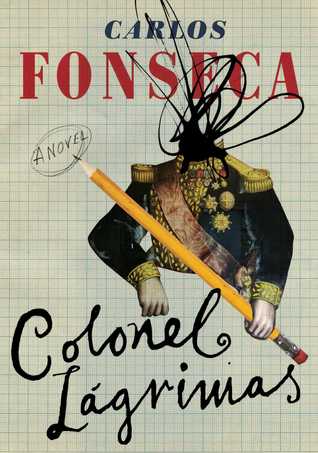

Carlos Fonseca’s Colonel Lágrimas is a novel that deals with the attempt of mathematician Alexander Grothendieck to isolate himself in the Pyrenees and devise a formula that encapsulates the whole of the 20th century. To do so he invents different personalities, all with different lives and interests — Chana Abramov, a woman obsessed with painting the same Mexican volcano a thousand times, Vladimir Vostokov, an anarchist in battle with technological modernity, and Maximiliano Cienfuegos, a simple man who will nonetheless become the symbol for the Colonel’s as well as Europe’s restless political conscience. Grothendieck’s own life story traverses the 20th century, from the Russia of the October Revolution to the Mexico of the anarchic 1920s, from the Spanish Civil War to Vietnam, back to France and from there to the Caribbean islands.

While reading it I thought of the theories of social scientist Gregory Bateson, who saw society as a set of systems with adaptive changes, dependent on feedback loops and the way multiple variables change and interact. This is a deceptively simple novel — turning its pages, one enters a kind of Zen state, as anecdote follows anecdote, and every word is located precisely in the place that seems right for it. But these are not just jewels moved by pincers on a metal plate. Through its form, Colonel Lágrimas dares to ask about the meaning of activity and the meaning of thinking, and embodies those questions in the structure of the text itself.

Each fragment is exquisitely written, and although not linear, the carefully phrased thoughts seem to be in an order that makes sense. If one were to be swapped out, however, it would not fundamentally dislodge the architecture of the work. Every individual “idea” contributes to the anecdotal edifice, but the book does not really depend on any one of them, in the way a formula depends on the variables that comprise it. Just as in Bateson’s theories, the pieces interlock in interactive ways that suggest a meaning beyond the individual parts. Any “formula” devised by Grothendieck would have to be dextrous enough to take these billions of feedback loops, sequences and interactive mechanisms into account, no minor undertaking, perhaps even impossible.

Colonel Lágrimas embarks on these abstract challenges in a way that is both beautiful and analytical — it doesn’t surprise me that Fonseca used to want to be a mathematician. Born in Costa Rica in 1987, he grew up in Puerto Rico. Now he lives in London and teaches at the University of Cambridge. The book was originally published by Anagrama, and was translated for Restless Books by Megan McDowell, who has also worked on Juan Emar, Alejandra Zambra, Carlos Busqued and a number of other authors.

Jessica Sequeira (JS) : How did you decide to write this book? In what ways does it link to your life experiences and to your studies? (It doesn’t have to, of course, but I wonder if there’s a connection.)

Carlos Fonseca (CF): I think most books are the product of a constellation of obsessions. I started writing Colonel Lágrimas as soon as I saw that many of my obsessions coincided within the same structure: my obsession with Chuck Close’s hyper-realist portrait paintings, my obsession with Alexander Grothendieck’s life as some sort of allegory of the twentieth century, my obsession with archives and archival-novels. When I started writing it, I was finishing my doctoral studies and I somehow imagined the novel as a form of escape from academic studies. Then again, you can never escape your obsessions. So the novel ended up addressing some of the ideas that intrigued me at the time: the idea of a history as a giant museum, the inability to pass from thought to action, the Borgesian notion of history being reduced to a giant encyclopedia or archive. And then, there is also the story of how – as an adolescent – I wanted to be a mathematician. Perhaps, now that I think about it, the novel was a way of rethinking my past.

JS: The colonel seems to face a similar set of questions a historian would. While reading, I noted some of his possible confusions, which I’ll copy here:

Is history a science? Is the attempt to create a blueprint misguided if we’re talking about human endeavor? Or can one look for a pattern there as well? If so, how should one go about trying to find it? Is it best to remove oneself from the world to ensure peace of mind and the tranquility necessary for tracing larger arcs? Or should one try to be as actively engaged in daily life as possible? Do the aims of history writing undergo development, in the same way that ideas of modernism marked a literary shift, partly in response to scientific discoveries? And is there some shining pattern or arch-truth behind these changes? Or is history just an infinite parade of possible anecdotes to arrange, catalogue, exhibit, assemble and frame in a Duchampian exercise, like a box of old film reels? Can the historian in his observational role play some part in affairs, creating change through his attempt to understand? Or is this withdrawal into the imagination folly? My question for you is how you see history, and how is it different or similar to the colonel’s?

CF: I am fascinated by history and I like the image of the historian as someone lost in a giant archive, shuffling around documents as if they were pieces in a jigsaw puzzle. And you are absolutely right: I am interested, not so much by the figure of the historian as he who finds the “truth” about history, but rather as he who recontextualizes and reframes the fragments of history. As you note, this is a Duchampian gesture: what matters is the frame, the context. A playful take on history. In this sense, more than a scientist or even a historian, the colonel is a collage artist: like Walter Benjamin before him, his idea is to construct a book in which every single forgotten fact is quoted, framed and analyzed. An encyclopedia of forgotten histories that would permit us to see the other side of History. On the other hand, the book is also critical of the image of that peaceful museum so often imagined as the peaceful resolution at the end of history. The question remains: how to think of political action within this giant museum? How to break open the museum’s doors and start running against the wind of history?

JS: You’ve mentioned Duchamp’s techniques. What is your relationship to art and how do you see contemporary literature as engaging with some of the techniques of the art world? (Do you see it doing this?)

CF: I have become, lately, very interested in art – and in particular conceptual art – as a territory lying at the limit of literature. I like Duchamp’s gesture of moving art away from the immediacy of the sensory towards the realm of the conceptual. Or at least, forcing us to reimagine what the relationship between the sensory and the conceptual, between feeling and thought, might be, beyond a mere contradiction. Ideas, too, have a body, I would claim. I see contemporary art as a playful realm of liberty for the imagination and as such I see it as the limit towards which literature should aim. I think that to write alongside Duchamp – as writers like Enrique Vila-Matas, Mario Bellatín or Margo Glantz do – is to imagine literature as a realm where thought meets emotion. As Don DeLillo likes to say: “Writing is a concentrated form of thinking.” I like to think that Duchamp’s gesture is precisely this: to turn thinking into art and art into thinking.

JS: Do you think of yourself as influenced by Puerto Rican or Costa Rican writing in any way? Or do you think nationalistic categories aren’t important?

CF: Influences are a tricky subject. I think you end up being influenced by much more than you imagine or intend. In this sense I can only hope to be influenced by both the Puerto Rican and the Costa Rican literary traditions, traditions which I have read passionately and which abound in wonderful writers. I like to think that just like each writer has two parents, each writer inherits, indirectly, two different traditions. In my case, being born in Costa Rica and raised in Puerto Rico, I like to think that perhaps a novel like Colonel Lágrimas is the strange offspring of the Puerto Rican baroque writing, on the one hand, and Costa Rican minimalism and experimentation, on the other. While writing the novel I kept thinking that the playful narrator had much to do with the voyeurist narrator in Luis Rafael Sánchez’s 1976 novel La guaracha del Macho Camacho, a novel that fascinates me due to its rhythm and narrative techniques. Meanwhile, I also kept thinking about Carmen Naranjo’s 1982 novel Diario de una multitud, an experimental novel that always reminds me of a set of Russian dolls. I don’t think national categories should be abolished but rather rethought or disrupted in innovative ways. But, I guess at the end of the day, I agree with Italo Calvino’s quote: “The ideal place for me is the one in which it is most natural to live as a foreigner.” The writer always has to be a bit out of place, he has to become a bit of foreigner even to himself. Writing is, in a way, another form of exile.

JS: In such a globalized world and with your experiences and influences in particular, do you still think “Latin American literature” makes sense as a phrase?

CF: I think “Latin American literature” only makes sense as an anthropological phantasy: as the label others give us, that is to say, as a particular lens through which the world sees us. I only figured this out when I arrived to study in the United States. Until then, it had always been a pain for me to explain my double-nationality to others: the way I was both Costa Rican and Puerto Rican. This was solved as soon as I arrived to the United States. Suddenly, I figured others had decided for me: I was Latin American. Like any other identity, this was, after all, nothing else but a mask. But masks and phantasies are also real. I think, beyond asking whether it exists or not, it is important for Latin American writers to play with this phantasy: to play with the anthropological phantasy that is Latin America in the eyes of the world. We always need to rethink the phantasy in order to critique it, I would claim. I also think that these broader categories end up helping writers from peripheral countries. If you stay at the national level, you keep reproducing the hierarchies dictated by the market: unknowingly, you keep speaking about Argentine, Mexican and Colombian writers, just because their market visibility is greater. Latin America as a category gives space to writers from countries that wouldn’t have visibility otherwise: countries like Ecuador, Paraguay, or Bolivia, just to mention a few.

JS: The Restless Books page refers to a “new Latin American boom”. Do you think that this term is legitimate? Or do you think phrases like this should also be abolished?

CF: Besides it being legitimate or not, I understand what they seem to be referring to: let’s say that in the post-Bolaño literary landscape, Latin American writers have gained a heightened visibility. Latin America – whatever that might be – is seen as a territory of literary innovation, as an exciting place where new voices can be found. The Bolaño phenomenon – for good or evil – transformed the way international publishers see our work and allowed for the region to be reimagined, no longer as the land of magical realism, but rather as the land of avant-garde innovation. I think this is a great step forward, independently of whether it comes with an actual boom or not. Of course, it does hint at the fact that the boom is still present in our imaginations as the golden age of Latin American literature: a spectre that never gets tired of haunting us.

JS: What writers or artists are important for you? Who do you like to read, from the past and present? How have you been influenced by the work of your teacher, Ricardo Piglia, and how does your work break from his?

CF: The other day I was rearranging my library, so I had time to think about this: which author to place alongside which author, who to give the best spots and so on. I guess, at least right now, the names in the main shelves are the following: Faulkner, Machado de Assis, Borges, Sebald, DeLillo, Lispector, Perec, Sarraute and Piglia. Then, next to them: Bernhard and Calvino. From each I have a particular memory, and perhaps my favorite is Faulkner, but with regards to this novel, I think the most important author was Machado de Assis whose Memórias Póstumas de Brás Cubas (published in the UK as Epitaph of a Small Winner) is a fascinating inheritor to Sterne’s Tristram Shandy: a playful experiment in narration. I love the idea of thinking of Machado as a black nineteenth century Brazilian predecessor of Borges, another author that is always central, not only to me, but to most writers in general. Regarding Ricardo Piglia, there is no doubt I am highly indebted to him, not only for his generosity and his amazing lectures, but for his capacity to redefine the way we read nowadays. Very few people, if any, have reimagined the figure of the reader in such a radical manner.

JS: In what direction is your current work headed?

CF: As of late I have become obsessed with obsession. I have become fascinated with protagonists whose engagement with their fixed ideas leads them to that shaky territory between art and science, between madness and reason, between art and nonsense. I am more and more interested by so-called outsider artists: artists working in the realm of that which Jean Dubuffet called “Art Brut”. Artists who don’t see themselves as artists. I see in them a metaphor of art itself, as well as a new way of linking thought and art.

JS: It’s fashionable to glamorize action in the world, and criticize thinking. While your book criticizes somebody who thinks too much, it also gets at many of the subtleties and pleasures of thought. How do you conceive of the relationship between thought and action? Do you think there is still a role for the observer in a world so oriented toward the glamorization of the “event”?

CF: This was one of my greatest obsessions while writing the novel. I wanted to explore the relationship between thought and action. Most people, when they read the novel, say that in it nothing happens. I accept these comments gladly precisely because I was interested in producing such a space of tedium, boredom and thought. A space which, like a museum, has secluded itself from the world in order “to think” the world, but where nothing necessarily happens, at least in the sense of the action to which we are accustomed. The protagonist of the novel, the colonel, belongs in fact to that strange sect of explorers of the negative which Enrique Vila-Matas has so well described in his book Bartebly and Co. Like Bartebly and like Alexander Grothendieck, upon whose life story the novel is based, the colonel decides one day to renounce the life of action in order to dedicate himself solely to the life of thought. I am fascinated by such characters: characters which one day decide to devote themselves to a conceptual project that might at first sight seem absurd, characters like the protagonist of Thomas Bernhard’s Correction. I am interested in sketching out how thought is also a type of action, perhaps the most beautiful and contemporary of them all. The only action that truly changes the world.

—Carlos Fonseca & Jessica Sequeira

x

Carlos Fonseca Suárez was born in Costa Rica in 1987 and grew up in Puerto Rico. His debut novel, Coronel Lágrimas, was published in Spanish by Anagrama and in its English translation, as Colonel Lágrimas, by Restless Books. His work has appeared in publications including The Guardian, BOMB, Minor Literatures, and The White Review. He was recently selected as one of the twenty new young voices in Latin Literature by the FIL Guadalajara. He currently teaches at the University of Cambridge and lives in London.

x

Jessica Sequeira is a writer and translator born in California, at home in Buenos Aires. @jess_sequeira

x

xx

x