.

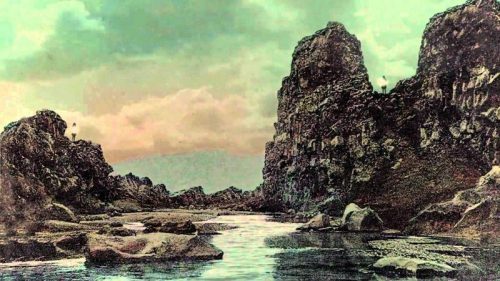

A flurry of snow in the darkness taunts frames Inga Birgisdóttir’s film for Sigur Ros’s “Varúð.” Then a darkened landscape, a pink hue as the sun rises. I hesitate to interpret this as a sunrise though, as this is a mostly gloomy landscape, as though Turner had an extended stay in Iceland and discovered he loved darkness more than light.

Only by the end of the film, when what light there is sinks into darkness and the flurries return do we get the sense that a day has passed. This is winter here, too, flurries stuttering our eyes, a reaching out to connect across the darkness, the scraping of skates on the tennis courts turned ice rinks, the wails of the snow plow blades shuddering on the next street over. We fall we fall we fall on the icy steps, reminding ourselves of mortality and other cold Icarus dreams.

What rises out of the darkness of Birgisdóttir’s film is a painterly landscape, Turner-esque, equal parts realism and psychological. The Icelandic Arts Centre describes her work as “a game of layers, both in her smaller collages and her bigger wall-pieces, as everywhere in her imagery one will find a mixture of old national emblems, waterfalls, mountains, and animals. Nowhere does Ingibjörg leave an empty space, evoking a Baroque-era fear of emptiness. Her symbols can be interpreted in various ways in a broad art historical context; all reveal evident sources of inspiration, especially Surrealism. As she samples and mixes from various fields, Ingibjörg’s ornateness nevertheless strips these symbols of meaning, leaving only a play of forms and giving her art a playful dimension.” She is a visual artist who Frankensteins her images together, suturing them into beautiful monstrosities.

This film sneaks up on you. When you realize there is light, it is already gone. When you notice a cloaked figure on the hill, you wonder how long it’s already been there. Then another arrives. It is paradoxically a meditative film, which first suggests we watch as we would look at a painting, but then the painting betrays us and changes as figures appear. Each time they appear it as though they were always already there, watching, waiting to be noticed. I was always late.

Film theorist Linda Williams would tell us that when we chase a film and arrive too late that there’s a bit of horror to it. Yet the figures are not in themselves scary, merely ominous. They appear on the ridge, flashing morse code messages out into the darkness and light, calling for someone, calling for a response. Then they find the response in each other. Birgisdóttir times the crescendos of the song with flurries of snow and then the arrival of subsequent figures in the landscape. These are indecipherable love letters for those of us who do not know the code, pleas across the barren landscape, across the winter light. A desire to connect.

As they appear, they outnumber us, their figures all eerily similar. Freud suggested there is something uncanny in twins. he would probably have winter nightmares with these proliferating figures.

Birgisdóttir’s film is part of the Sigur Ros Varaki project and she made two films for that, the other Ekki múkk:

Numéro Cinq has featured two other articles on the Varaki films: Ryan McGinley’s short film “Varud” and Dash Shaw’s “Seraph.”

— R. W. Gray

.

,