W. S. Merwin’s Garden Time is a book about aging, about the practice of trying to live one’s life in the present. The recurring themes are loss and old love, memory and forgetting, and a kind of precognition that the whole of what we are was with us from the beginning —Allan Cooper

Garden Time

W. S. Merwin

Copper Canyon Press, 2016

96 pages, $24.00

.

We seem to live many lives before we die. One of the great joys of growing older is when one of those accumulated moments comes back with sudden clarity, when we least expect it. We are young and old, male and female, and sometimes even two redstarts perched on a plum twig return to find us:

…in the dusk

two redstarts

close together before winter

lit on a plum twig

near my hand

and stayed to watch me

(“Portents”)

W. S. Merwin’s Garden Time is a book about aging, about the practice of trying to live one’s life in the present. The recurring themes are loss and old love, memory and forgetting, and a kind of precognition that the whole of what we are was with us from the beginning:

ONE SONNET OF SUMMER

Summer has come to the trees reaching up for it

it has come in daylight without a sound

it arrived when the trees were dark in sleep

they dreamed it and woke knowing it was there

but I am an autumn child and my first

summer I was here but was not yet born

I heard the leaves whisper on their branches

and the cicadas growing in their song

I listened to all the language of summer

in which the time was talking to itself

I was born in autumn knowing the sound of summer

There are many questions in this book, questions about life, death, and the passage of time. The opening poem repeats the phrase “would I love it” several times like a mantra:

THE MORNING

Would I love it this way if it could last

would I love it this way if it

were the whole sky the one heaven

or if I could believe that it belonged to me

a possession that was mine alone

or if I imagined that it noticed me

recognized me and may have come to see me

out of all the mornings that I never knew

and all those that I have forgotten

would I love it this way if I were somewhere else

or if I were younger for the first time

or if these very birds were not singing

or I could not hear them or see their trees

would I love it this way if I were in pain

red torment of body or gray void of grief

would I love it this way if I knew

that I would remember anything that is

here now anything anything

Memory is a major theme in “Black Cherries”– how we store the past, those moments of clarity and understanding and carry them forward. In this poem a synergy is created between the goldfinches “flutter (ing) down through the day” and Merwin eating black cherries:

Late in May as the light lengthens

toward summer the young goldfinches

flutter down through the day for the first time

to find themselves among fallen petals

cradling their day’s colors in the day’s shadows

of the garden beside the old house

after a cold spring with no rain

not a sound comes from the empty village

as I stand eating the black cherries

from the loaded branches above me

saying to myself Remember this

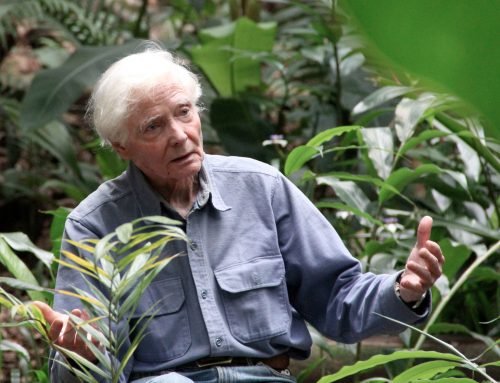

A small poem called “Rain at Daybreak” is about living firmly in the present. It ends with a Zen-like koan: “there is no other voice or other time.” W. S. Merwin first came to Hawaii to study Zen Buddhism with Robert Aitken in 1976. Merwin doesn’t wish to chat about Buddhism in a casual way, and I respect that. But in an interview with Ed Rampell of The Progressive (October 25, 2010) Merwin talks a bit about this, and the connection between Buddhism and Christianity:

Certain things, if one pays attention and is concerned about them, in one’s temperament, in one’s outlook on the world, in one’s attempt to understand something about the world, certain things confirm what one is groping one’s way towards. I didn’t have the words for that, but there it is… For me, there are various places where one can find things like that. Blake, or Daoism, there are even things in the New Testament. I’m not a Christian but I think Jesus was an amazing occurrence on the planet and I think we’ve made of him something that he never was or ever wanted to be. But there are incredible things that he said. I heard a Japanese teacher say where Christianity and Buddhism are very close is when Jesus said: “The kingdom of heaven is within you.” If it’s not there, it’s nowhere.

Merwin also understands that at this time, many of us have less and less knowledge of the natural world. In this excerpt from “After the Dragonflies” he begins:

Dragonflies were as common as sunlight

hovering in their own days

backward forward and sideways

as though they were memory

now there are grown-ups hurrying

who never saw one

and do not know what they

are not seeing

Rather than being stewards of this planet, we have literally lost touch. Merwin seems to imply that what we do not know, or do not want to know diminishes us. The poem ends with “there will be no one to remember us.”

And yet there are ways to reconnect with the world. Thoreau built his small cabin, ten feet by fifteen feet near the shores of Walden Pond as part of his mission to live in a closer relationship with the land. For Merwin it was Maui, where he bought three acres of land depleted by erosion, logging and pesticides. Over the years, he and his wife Paula built a house there and began restoring the land. The Merwin Conservancy is now 19 acres and contains over 800 varieties of palm trees. It is “one of the most comprehensive palm forests in the world.” (Merwin Conservancy, biography.) Merwin doesn’t speak of meditation as such in his poems, specifically Zen sitting or zazen, but it seems that his translations, his own poetry, and his work as a gardener in his palm forest are all a personal form of meditation. We could say there is a connection between his creative life, his gardening life, and what we might call his spiritual life. They flow into one another and form a kind of third consciousness. When we spend more time in the natural world, our reservoir of fear, which is immense in this century, tends to lessen. Then there can be commerce between the human world, the natural world, and the invisible world where the old gods – if we’re lucky – step out to meet us. In “Voices Over Water”, Merwin says “There are spirits that come back to us…some of them come from the bodies of birds.”

§

There are moving, heartbreaking poems about childhood in Garden Time. As a friend said to me recently, when we hear the right words that express our loss and our grief, our visceral response is to weep. “Loss” is about his stillborn brother and how his mother tried to come to terms with it. Merwin understands loss; he also understands how our attempts to dismiss it rarely work. In this poem Merwin faces it head on, naming it in the opening stanza:

Loss was my brother

is my brother

but I have no image of him

his name which was never used

was Hanson

it had been the name

of my mother’s father

who had died as a young man

her child had been taken away

from my mother before

she ever saw him

to be bathed I suppose

they came and told her

that he was perfect in every way

and said they had never

seen such a beautiful child

and then they told her that he was dead

she sustained herself by believing

that he must have been dropped

somewhere just out of her sight

and out of her reach

and had fallen out of his empty name

all my life he has been near me

but I cannot tell you anything

about him

In the second poem Merwin becomes his mother’s way to find her life again – the laughing child. Nowhere in this collection is the sense of the past as extant in the present more evident. It is one of the finest poems of the last 60 years.

THE LAUGHING CHILD

When she looked down from the kitchen window

into the back yard and the brown wicker

baby carriage in which she had tucked me

three months old to lie out in the fresh air

of my first January the carriage

was shaking she said and went on shaking

and she saw I was lying there laughing

she told me about it later it was

something that reassured her in a life

in which she had lost everyone she loved

before I was born and she had just begun

to believe that she might be able to

keep me as I lay there in the winter

laughing it was what she was thinking of

later when she told me that I had been

a happy child and she must have kept that

through the gray cloud of all her days and now

out of the horn of dreams of my own life

I wake again into the laughing child

The Canadian poet Alden Nowlan said we experience these moments somewhere “between tears and laughter.”

§

Many of us would agree that poetry is one of our oldest and most poignant forms of expression. The poem is a container for those things that move us profoundly but which many of us can’t quite put into words. The poet names things, gathering them in images which centre and focus our experience. Here are a few of Merwin’s ideas about the uniqueness of poetry, again from The Progressive interview:

Poetry uses the same words as prose but it’s physical. It was that way – poetry may be the oldest of the arts. Because it’s probably as old as language itself. Its closest relation would probably be music and dance. Those three things together; before the visual arts, the first Paleolithic paintings, and things like that. Anyway, it’s very, very old, and theories about the origins of language suggest a different source for it, very close to poetry, in the origins of language itself. A number of theorists think it comes out of an inexpressible emotion, something that was just so, so urgent that the forms of expressing it weren’t adequate to it.

The final poem in Garden Time is called “The Present.” We don’t know for sure if Merwin means the present, the now, or a gift which has been given. Coleman Barks in one his poems says “mountain laurel overhanging the water, letting blossoms go to keep us constantly in the same thought with the falling rain: the gift is going by.” Merwin says:

As they were leaving the garden

one of the angels bent down to them and whispered

I am to give you this

as you are leaving the garden

I do not know what it is

or what it is for

what you will do with it

you will not be able to keep it

but you will not be able

to keep anything

yet they both reached at once

for the present

and when their hands met

they laughed

Hands touching, then laughter: W. S. Merwin catches those urgent, inexpressible moments in his poems. Like Han Shan, the Chinese recluse poet, he faithfully tends the garden of compassion and sudden awareness that is inside all of us.

—Allan Cooper

Allan Cooper has published fourteen books of poetry, most recently The Deer Yard, with Harry Thurston. He received the Peter Gzowski Award in 1993, and has twice won the Alfred G. Bailey Award for poetry. He has also been short-listed three times for the CBC Literary Awards. Allan intermittently publishes the poetry magazine Germination, and runs the poetry publishing house Owl’s Head Press from his home in Alma, New Brunswick, a small fishing village on the Bay of Fundy.

N5

Thank you for this. Beautiful

Thank you, Allan. This gives a very sensitive introduction to Merwin’s powerful poems.

Thanks for doing this fine review. Now, I’m going trough my bookcases to find what I have of Merwin’s poems.

A well-written and well-considered review — thank you.

I greatly admire Merwin and “Black Cherries” is a beautiful poem, but it has always confused me. It’s setting is explicitly late May and yet the narrator is eating black cherries off a heavily-laden tree — cherries do not ripen until July/August in the continental US (and do not grow at all in Hawaii). Is May the present moment and the cherry-eating some memory from out of the past when the narrator’s past self said “Remember” in the past moment? Or is this a Frost moment, when one must be “versed in country things”?