x

First Kiss

To get to the cemetery you had to come along our street, under the dark archway of chestnuts and maples. It must have been enchanting for the mourners, or depressing, or something. And then the thonk of plums as we pelted the procession.

Our theory was that people would be too grief-stricken to come after us, or too worried about their good clothes. This is when we were twelve or so, too old for such idiocy, but anyway. We’d load an apple basket with plums fallen from the Barfoots’ tree, and we’d duck down behind the foundation wall in the abandoned lot next to Shithead’s house a few blocks down from mine. There’d be Shithead, and Dunk, and Kev maybe, and me. Somebody would yell “Fire!” and we’d fire. The plums were soft and slippery, half rotten half of them, so you couldn’t really pitch them, more like catapult them, cupping them in your palm. Most of them would miss, but not all of them.

Just one time the procession stopped. I don’t know how many funerals we bombed that year, it seemed like a lot but it was probably only a half dozen or so. Mostly the vehicles would just keep going, crawling along like a battalion of tanks in a movie. The hearse (you got double points if you hit that, though we never actually kept score), then a limo or two, and then a bunch of just normal cars, a line of variable length depending on how much the person had been loved, I suppose, or by how many people.

But this time the limo stopped, the one behind the hearse. The hearse kept going—maybe he didn’t check his mirror, or maybe he didn’t feel right stopping with a dead body in back. But the limo stopped, and the whole procession behind it. Out of the limo crawled this guy. Like my father, that sort of age, but smaller and more angular, and of course dressed head to foot in black. He looked over our way—we’d neglected to duck back down, too surprised I guess. And he came charging.

We had a plan, which was to split up. That was our whole plan. I don’t know where the others went, but I took off for home, down the back lane. When it occurred to me how stupid that was, I cut through a couple of yards over towards the school. The mourner had singled me out, the biggest and fattest of this gang of fat little pricks, and he was coming hard, I could hear him. At one point the nerve just went out of me. The mourner found me sitting in a patch of leafy greens in somebody’s garden, crying like a five-year-old.

And what he did was he comforted me. He told me he’d been young once too, young and senseless. He was still huffing from the run, and he patted my arm and told me to go ahead and cry, that there was no shortage of things to cry about in this world. He asked me if I minded if he had a little cry too, and he had one, a few dry-eyed sobs which turned into a laugh. “Is that really the way I weep?” he said, and he wept some more and laughed some more. He had a beard, which he gripped as though to keep his face from slipping off.

By this time my fear had deepened to the kind you don’t cry about. I sat still while he told me about somebody named Neil, a friend from his childhood. It may have been Neil’s body in the hearse, but I’ve never been sure of that. What I do know is that Neil had a major overbite as a boy, and that he was crazy about birds. He could identify a bird from a silhouette in flight, or from a snippet of song. Warbler, thrush, you name it.

After a while the mourner sort of came to himself, remembering about his funeral, I suppose. “Yep, that Neil,” he said, shaking his head. Then he gave me another pat, stood up and trotted away.

It was dinner time, but I took the long route home, past the park. There was a girl named Yasmin, an almost-cute girl from my grade, just saying goodbye to some friends at the baseball diamond. “Wanna walk?” she said, and she came up beside me. We only half knew each other and hadn’t much to talk about. Mostly she kept staring at me, and finally she said, “Have you been crying?”

I wiped my face and said that somebody had died.

“Oh,” she said. “I’m sorry about that. Who died?”

I said, “I don’t know.”

Yasmin laughed. I remember her laugh sounded like some people’s bawling. I stepped in front of her and turned and kissed her on the mouth, which I’d never done to anybody before. Yasmin kissed me back, or at least she didn’t pull away. She and her friends must have had cigarettes, because she tasted like my mother’s breath after she’d been out on the porch by herself. I put my hand on her cheek, Yasmin’s cheek, a hand still sticky and sweet with rotten plum.

My wife, Gina, doesn’t buy it. She simply won’t believe that what happened that day is at the root of what she calls my “problem.” Why call it a “problem” in the first place, if it isn’t actually a problem? That’s what I keep asking her. And she keeps laughing, which I love (Gina laughs like a cat after a bird it can’t quite reach). All that matters is that I want her, and that I’ll never stop. I’ll never stop.

xxxx

Word of Mouth

Stan’s first career was inspired by the swoop of a heron past the window of the family cottage when he was a kid. Fish were floating to the surface of Sahahikan Lake that year, and talk was that soon birds and other predators too would be succumbing to the chemicals that had been allowed to seep into a feeder stream. Stan was already disturbed by this thought, and by the fact that he and his brother had been barred from the lake, but it was the thrill of the heron’s heavy flight that truly got to him, the notion that something so alive could soon be dead, and dead because of people. Ten years later he emerged from school with a degree in marine biology. Thirty years after that he cleared out his desk at Rant Cow Hive.

Fired, laid off, whatever—the agency (actually Envirowatch, but Stan and his colleagues diverted themselves creating various anagrams) was being eviscerated, middle-aged, mid-rank characters such as himself being set unceremoniously free. A trauma, not because Stan loved the job (he resented it, the long slow failure it made of his life), but because he’d just ended his marriage, and vacated his house, and was running short on things of which to be dispossessed.

Stan’s second career was inspired by Mr. Neziri, the man across the hall from his mother at the hospital, where Stan spent more and more time in the aftermath of his sacking. Mr. Neziri and Stan’s mother were both doomed, but they were going about their deaths in radically different ways. Stan’s mother, for instance, was deaf and almost mute. Save the odd noisy non sequitur (“Won’t you stay for dinner?!?” when she was being fed through a nose tube), she held her peace about her predicament. Mr. Neziri, on the other hand… What was that sound he made? A sob, a moan? A sob-moan, a yowl-howl, a wail-whimper. It was nothing, there was no word. Actually, there was what sounded like a word once, out in the middle of one interminable jag, but in a language unknown to Stan. And then back to the meaningless caterwaul once more.

Meaningless, that was the key. To mark death you had to make a sound that carried no meaning at all, that was in fact a constant obliteration of meaning. Mr. Neziri was mourning himself, articulating his oblivion before it arrived. But what of those, such as Stan’s own mum, who couldn’t muster the strength or the vision for this task? Who would cry out for them? Didn’t there used to be professional mourners? Why shouldn’t there be once more?

Stan’s old boss Bernie (who’d also been axed) had been sending Stan links to articles called things like “Second Time Around” and “Age as an Asset” and “Repurposing the Middle-Aged Man.” What you didn’t have anymore was youthful energy and enthusiasm. What made up for that was wisdom, worldliness. Your first career had been about duty. Your new one would be about love. You were done with obligation, time to follow your bliss.

Love? Bliss? Demand, there was plenty of that. Stan was one of about a billion people soon to be robbed of somebody. His fellow boomers alone, with all their ailing parents…

He began his rehearsals at “home,” the not-quite-wretched bachelor suite out of which he kept on not moving. He’d knock back a half-mickey of vodka (a poor man’s peyote, is how he thought of it, opening him to shamanic energies), bring the lights down to a funereal gloom and get started.

The idea was to have no idea. Stan’s sound needed to be free of all influence and intent, each act of mourning incomprehensible in its own unique way. He’d made the mistake of starting with online research and now needed to erase the memory of other wailers (the Yaminawa of Peru, the Nar-wij-jerook of Australia), along, of course, with the memory of every other human utterance he’d ever heard. To be meaningless, a cry needed to be innocent of all allusion and all shape. Free jazz but freer, no key, no time signature, no consistency of tone, tempo, timbre. Stan had a decent voice (he’d rated a solo on “Softly and Tenderly” with the boys’ choir back at St. Joe’s), which was both a blessing and a curse. What he was singing now was scat but more so, a series of sounds denuded of history and prospects, a pure racket. At every moment he needed to be saying nothing.

There was a dry spell, sure. Stan ran a few ads (“When it’s forever, you want the best!”), but he knew it was personal contact that usually got you your start. And so it was. A first nibble came from his brother, who wrote to say that he’d be staying on with his firm in Fukuoka for another year because of a death one rung up the ladder. Stan replied with an update on his new career, hinting that he’d be open to a contract abroad, to which his brother came back with, “You need help, man. Seriously, I love you, but you need help.” Promising. Any significant insight was bound to be met at first with dismay. How had people responded when they first learned the fate of the natural world?

And then the breakthrough. When the police showed up a third time in response to complaints from neighbors (whose wall-pounding served as accompaniment many nights), Stan got chatting with one constable while the other wrote up his warning. An almost frighteningly empathetic individual, this guy turned out to have a sick sister (Cushy disease, could that be right?) who was busy planning her own gala funeral. “A professional mourner,” he mused. “Hey, she might just go for that!”

The audition took place in the sister’s hospital room. On another ward, in another part of the city, Stan’s mother and Mr. Neziri were still at it. Stan had two months of daily practice under his belt by this time and was beginning to feel some confidence. Indeed, the audition went well. One little phrase from “Smoke on the Water” snuck in, but his bellowing was otherwise bereft of sense, of any discernible pattern or meaning. The siblings were perfectly devastated, as were the mourners at the sister’s funeral a month or so later.

From there, things just sort of took off.

x

Your Wellness This Week

Dear Doctor Barry,

My wife went through a bad time last year. She had a cancer scare, and instead of being relieved when that was over, she got anxious and depressed. At my urging she saw a psychiatrist, who tried her on a few different medications. She’s now on something new called Liberté, and for the most part it seems to be working. I’ve got my wife back!

I do have concerns, though. My wife has never been phobic, but she’s suddenly developed a fear of branches (that’s right, tree branches) and of the colour turquoise. I’m pretty sure she’s got other phobias too (is it possible she’s afraid of my chin?), but we haven’t been able to nail them down for sure. Part of the problem is that she doesn’t seem to care about them, or about much else either. She’s cheerful, but I guess the word is blasé.

Could the new drug be responsible for what’s going on? Help!?!

R.S.

x

Dear R.S.,

Though Liberté is proving effective as a treatment for general anxiety, it was originally developed to combat thanatophobia, defined as a morbid or persistent fear of death. The health scare that preceded your wife’s depression likely caused her doctor to zero in on that issue.

The main component of Liberté is a derivative of toxoplasma, which you may recognize as the parasite associated with cats that can be harmful to immune-compromised individuals and unborn children. (Pregnant ladies, stay away from that litter box!) Researchers discovered that mice infected with toxoplasma lost their fear of cats. Extracted and modified, the same agent turns out to be well-tolerated by humans.

Clinical studies showed that this agent suppressed the human fear not just of predators but of death in general, and thus reduced anxiety. Some unfortunate side effects emerged, however, in particular lassitude and even ennui. Having lost their fear of death, people seemed to lose their zest for life. As one subject expressed it, “Without a fear of death, our stories have lost their sense of an ending. We’re left with a beginning and then a great big pointless middle.”

To combat this troublesome impact, BoothTiborMcGuane decided to add a psychostimulant to their version of the drug. The product known as Liberté includes a small dose of amphetamine and dextroamphetamine salts, the sort of combination found in ADHD medications. This stimulant has probably helped maintain your wife’s energy and initiative to some degree, but has perhaps contributed to secondary anxieties. Why her anxiety has manifested in these particular forms may remain a mystery. Incidentally, the fear of chins is termed geniophobia and is more common than you might think.

It’s a matter of trade-offs. Are these new fears preferable to the overarching fear from which she suffered before? That’s something she should discuss with her psychiatrist. In the meantime, you can of course support her by acknowledging the reality of her fears, even when they seem ludicrous to you, and by reassuring her that a certain level of apathy is natural for someone on this medication. You can also remind her that even though she doesn’t fear death anymore, she’s still going to die. Exercise is important too, and an active social life, areas in which you can certainly encourage her.

Dr. B.

—John Gould

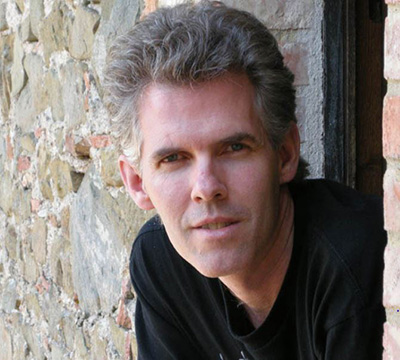

John Gould is the author of a novel, Seven Good Reasons Not to Be Good, and of two collections of very short stories, including Kilter, a finalist for the Giller prize. The stories appearing here on NC are from the manuscript of a third such collection. Gould has worked as an environmental researcher, tree planter, carpenter, and arts administrator. He served for years on the editorial board of the Malahat Review and teaches writing at the University of Victoria.

x

Thoroughly enjoyed these.

Wonderful stories.