The real strength of Bret Easton Ellis and the Other Dogs isn’t that it hews closely to this one prescribed theme. In fact, the reason this book haunts and horrifies and challenges us so much is that it strays so widely, and so wildly, from any fixed structure or approach. — Mark Sampson

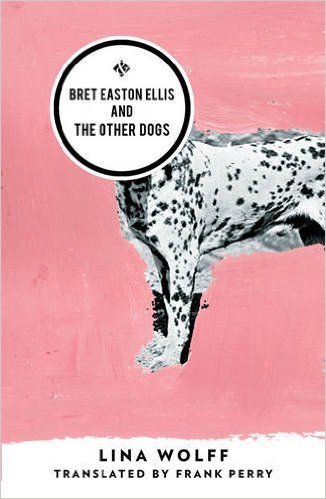

Bret Easton Ellis and Other Dogs

Lina Wolff

Translation by Frank Perry

And Other Stories, 2016

$15.95

.

Men are dogs. This is the prevailing theme of Bret Easton Ellis and the Other Dogs, a debut novel that has already turned Sweden’s Lina Wolff into a literary sensation. Wolff’s project – a text at once fragmented enough to pass for a short story collection and yet untraceably centred on the character of Alba Cambó, a writer of violent, horrifying tales who has been diagnosed with terminal cancer – draws a connection between the canine-like nature of human males and the limitations of revenge against their more animalistic natures by women. Setting Alba’s story mostly in colourful Barcelona, Wolff renders it into a kind of narrative kaleidoscope, told through the eyes of her friends, lovers, and acquaintances.

Wolff’s own life seems as kaleidoscopic as the story she has created. She has done stints in both Spain and Italy, and now lives in southern Sweden. She has published one previous book, a short story collection called Många människor dör som du (Many People Die Like You; Albert Bonniers Förlag, 2009), which was met by strong reviews. She writes with an unmistakable focus on feminism – but it is a peripatetic feminism, one that looks to travel widely across the expanse of gender dynamics, and to hit them from a multitude of angles. Ironically, one of her biggest literary influences appears to be French shit disturber Michel Houellebecq, whose own work makes a deliciously comic appearance in Bret Easton Ellis and the Other Dogs.

Wolff’s novel’s title is explained by the back-cover copy, but readers will be misled if they think the following is a summation of the whole book: “At a run-down brothel in Caudal, Spain, the prostitutes are collecting stray dogs. Each is named after a famous male writer: Dante, Chaucer, Bret Easton Ellis. When a john is cruel, the dogs are fed rotten meat.” In actuality, this sequence comes relatively late in the novel, and yet captures the very essence of book’s theme. Here it is, narrated by character named Rodrigo Auscias, a man who once had a threesome with Alba and one of her casual boyfriends:

We’ve got a kennel and the dogs in it are all named after famous writers, she had said. Whenever some guy pays us a visit and is nasty to us, we give the dogs rotten meat. I couldn’t help laughing at the whole idea at the time. Passive rebellion is what they call that, I informed her. When you’re powerless, passive rebellion is what you come up with. It’s also called projection. You make the dogs suffer for what the men have done to you because the dogs are weaker than you. It’s like a father who abuses his children because the factory owner has forced him to work too hard.

Rodrigo goes on to ask where the women got the idea from, and the say they were once visited by an “intellectual feminist” who planted the seed in their minds. This term, passive rebellion (one might also dub it a kind of low-level terrorism), has, the reader will now realize, played a huge role in the various chapters that have preceded this scene. This idea of punishing an animal for the sins of a person has appeared a couple of times already in the novel, with the murder of a canary in one chapter and the boiling of a cat in the other. With a sharp, unflinching eye, Wolff shows us that revenge can take many strange, off-kilter forms.

Yet the real strength of Bret Easton Ellis and the Other Dogs isn’t that it hews closely to this one prescribed theme. In fact, the reason this book haunts and horrifies and challenges us so much is that it strays so widely, and so wildly, from any fixed structure or approach. This lack of a traditional narrative arc allows Wolff’s imagination and talent to sore: there were several points throughout the novel’s episodic approach where I was wowed by her out-of-left-field audacity and the unexpected twists in the turn of events.

A summary of these sequences would prove to be as disjointed as the novel itself. The story begins with an unnamed narrator recounting the time that Alba was spending time with one of her lovers, a man named Valentino, and informed him after a romantic episode together that she was in fact dying from cancer and would not be around for very much longer. The novel then shifts and we soon learn who this narrator is: a young girl named Araceli Villalobos, who lives in the same apartment building in Barcelona as Alba. We learn that Alba is gaining notoriety in the neighbourhood for publishing a series of brutal, feminist-infused short stories in a magazine called Semejanzas (Spanish for “Similarities.”) The most memorable of these pieces involves a man who kills himself after humiliating himself at his own surprise party by farting loudly just before turning on the lights.

The story soon shifts as Araceli learns of a woman from South America named Blosom who is living with Alba. Alba attempts to pawn off Blosom to Araceli and her mother as a kind of live-in housekeeper. After that happens, Wolff takes us on a detailed, first-person tour of Blosom’s life. We learn that she was once married and had a young son who was killed in a traffic accident. We also learn that Blosom began an affair with a married man while working as his housekeeper, right under his wife’s nose. The tension in the household comes to a head during a scene in which Blosom is helping the wife, whose name is Jessica, take a bath. This was one of the most audacious scenes in a novel full of them:

“You’re a pretentious little ignorant cow,” Jessica cried. “Is that what got drilled into you while you were growing up, that there’s nothing more important than giving a man a child? Hah. Along with all those Venezuelan soaps you watch. that’s soft porn for old ladies, all of them thinking the best thing you can do for a man is to give him a child and then the women are left with chains around the ankles and a ring through the nose, stuck with life in a cage. Fortunately, Vicente doesn’t belong to the old school. He doesn’t actually want to have children.”

Our eyes met in the mirror on the other side of the bathtub. I hate you, I thought. I hate you so much it’s killing me.

“You’ve got something in your hair,” she said.

“What?”

“It looks like sperm.”

“Well it’s not that.”

“Would you mind washing it off, please.”

Bret Easton Ellis and the Other Dogs is full of these kinds of jarring, shocking sequences, and they infuse the novel with an inventiveness rarely seen in contemporary fiction. As we go along, the perspective of the book changes once more. By the time we meet a girl named Muriel, a classmate of Araceli’s at the translation school where she is studying, we get a sense of just how decentralized this book’s structure is.

Eventually we loop around to the story of Rodrigo. He has his threesome with Albo and her casual boyfriend Ilich. Ilich uses his cell phone to film part of the encounter and threatens to reveal the video to Rodrigo’s wife, Encarnación, unless Rodrigo agrees to help him. What does Ilich want? He wants Rodrigo’s help breaking in the Spain’s competitive timber market. It’s actually more compelling than it sounds. Rodrigo does what Ilich wants of him and he comes to think he is now free of the man. But Ilich shows up one day at Rodrigo and Encarnación’s apartment in a scene that is rife with domestic tension. The section concludes with Rodrigo watching as his wife descends into a harrowing alcoholism that he cannot stop.

Themes of cruelty and of vengeance churn through this book at every turn, to the point where such acts feel completely normalized. Yet Rodrigo, in detailing his encounters with Alba and Ilich, offers a powerful counterbalance to the notion “passive rebellion” discussed above:

I have no political convictions. I don’t give a damn about politics. People with political convictions frighten me. People who are willing to sacrifice themselves for an idea are also willing to sacrifice other people for the same idea. That applies to people who have been the victims of injustice as well. They are the most dangerous people of all because they believe themselves entitled to revenge.

This one passage helps to snap so much of this novel into focus. The idea that revenge is an entitlement, even if (or, in the case of passive rebellion, especially if) the victims of that revenge are not the same individuals who victimized you in the first place, feels very much like a contemporary preoccupation. The entire world, this book is seeming to say, is full of randomized violence and cruelty, and ideas of “motive” or “blame” may very well be passé in this new reality. Wolff’s dark vision of how our world now operates is a disturbing, but deeply compelling, one.

— Mark Sampson

NC

Mark Sampson has published two novels, Off Book (Norwood Publishing, 2007) and Sad Peninsula (Dundurn Press, 2014), a short story collection, The Secrets Men Keep (Now or Never Publishing, 2015), and a collection of poetry, Weathervane (Palimpsest Press, 2016). His stories, poems, reviews and essays have appeared in numerous journals throughout Canada and the United States. Originally from Prince Edward Island, he now lives and writes in Toronto.

Dear Mark– So you got hold of the plant in Lina’s photo, brought it home

to Canada, then promptly (assisted suicide) let it perish. Am I reading those two

photographs correctly?

Hey Leon – No, actually, Rebecca and I stole that plant from a Waiting for Godot production (they have since replaced it with a proper leafless tree) and attempted to grow tomatoes from it off our apartment balcony. The results were, naturally, a spectacular failure.