.

I

N THE 1940s, we travelled sixty miles in the old utility truck to visit my grandmother. She lived with my aunt Marjorie on the edge of the Liverpool Plains at the village of Bundella in northern New South Wales. Petrol was scarce and rationed, so we didn’t go there often, perhaps once every six months. We crammed in – my father and mother, my sister and I – bumping along the roads with the windows up despite the heat, because of the dust. It still seeped in through crevices in the dashboard and up through the floor. We drove from our hilltop house, past the small coal mine, then turned south, down the valley beside the wheat paddocks of Narrawolga towards Quirindi, but only as far as Quipolly. We crossed the rackety wooden bridge and turned west, then the scene opened out to the plains. They stretched as far as the distant blue of mountains. It was a good fifty miles from there, mostly across black soil, to my grandmother’s. The crags of the Liverpool Range loomed just ten miles to the south.

To me it was a magical place with rusty remains, like the single-furrow plough once pulled by heavy horses, my great-grandfather plodding behind. There were outbuildings of battered corrugated iron which included the wash-house. There were the old slab stables (part of the woolshed), housing the abandoned buggy and the sulky. Horse collars, harness and chains still hung from rusty nails and hooks. It was where my mother grew up.

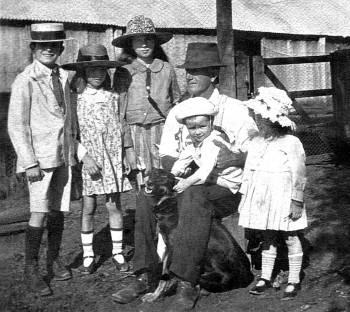

In 1918 by the woolshed, mother second left.

In 1918 by the woolshed, mother second left.

There were saddles in the harness shed and a rusted iron bedstead where mum had met the fox. There was the anvil, dull from neglect, the bellows and the tools. Bridles hung in a row from the vertical slabs and a side-saddle, the leather blackened, dried out, cracked and dusty. ‘Grandma Ewbank’s saddle’, Mother had said. It belonged to my great-grandmother who’d left Bundella in offended silence in 1908 when she was sixty-five. She had no further use for such a thing as a side-saddle.

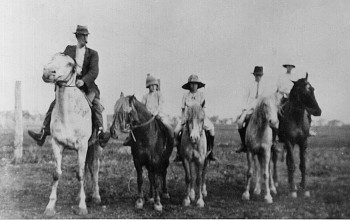

Now there were no horses. At night by the light of the kerosene lamp, I studied the faded snapshot of the man sitting tall on the high horse – my grandfather who died before I was born – beside four of his five children on horseback – my mother the young girl in the wide-brimmed hat on The Creamy.

Life at Bundella behind the village Store and Post Office was simple but tough – no electricity or gas, no town water supply (only the rain and it often didn’t rain very much), plus hard well water for the bath, heated on the fuel stove or in the copper, carted in a bucket to the bathroom. I’d sit with a cake of Pears soap in an inch of water at the bottom of the old white tub which had feet like a lion. And down the backyard I’d clutch the edge of the scrubbed pine seat in the lime-washed slab-walled dunny, holding my breath because of the smell as I balanced over the cesspit, hoping not to fall in. Then I’d open the crooked door with its leather hinges and run past the fowl house, scattering chooks and grey-and-white-spotted guinea fowl as they foraged in the yard. I’d detour through the wild garden, under the trees, round the shrubberies and scented flower beds, keeping an eye out for snakes.

My grandmother sold up in 1950 at the age of seventy. She moved from Bundella to the city with Marjorie. We went out in the ute to clean up the sheds. My father couldn’t come because the mine was flooded, so Charlie from the pit was at the wheel in his greasy hat. We squeezed in beside him, my mother in her best hat and gloves. I, being the smallest, had to straddle the gear stick that rose from the floor. There had been flood rains and the black soil road was treacherous. No dust but plenty of mud. Charlie smoked incessantly, rolling his own as he drove.

When we arrived, Marjorie was sitting as usual, prim-faced at the switchboard, her thick black plait pinned firmly over the crown of her head. She waved us a greeting but said to a subscriber at the other end of the line, ‘Sorry, the number’s engaged. I’ll try again shortly…Number please?’ In the kitchen, the heavy blackened kettle was boiling on the fuel stove and my grandmother made tea. Charlie ladled in the sugar, then tipped the tea into his saucer. He blew on it and drained it down.

Marjorie & my grandmother 1950

Marjorie & my grandmother 1950

My mother removed her hat, donned her overalls and went out to the shed. My grandmother temporarily took over the switchboard so Marjorie could lend a hand. She rushed up with a sack over her shoulder and dropped it with a clank on the ground. It contained rusting rabbit traps that were put to one side ready for the auction. A bonfire burned in the yard. Charlie hurled on everything my mother condemned to the flames. By evening the shed and other outbuildings were bare, the bonfire a heap of smouldering ashes.

The goods for the auction were piled high: saddles and pitch forks, axes and ploughs together with the mangle, the anvil and the galvanised iron wash tubs. At the centre of a heap of dusty objects I spotted the gleaming statue of Grace Darling.{{1}}[[1]]Grace Darling was an English heroine of Victorian times. As a young woman she rowed out through raging seas with her father to rescue survivors from a sailing ship wrecked on rocks in the storm.[[1]] She was about my height and I was seven. Jim and Fred from up the creek had carted her from the house. She’d always been in the dark hallway, peering out at the raging sea and that shipwreck. At least that’s what my mother said. She said Grace Darling was a heroine. Now she stood on her pedestal in the mud, holding the lantern high and gazing out across the sodden plain, her hair and gown, as always, blowing in the gale.

It was wet the day of the auction and a bleak wind scoured the paddocks. I peered out between the lopsided doors of the shed to watch old Johnny Ferguson playing the auctioneer. He stood on a battered crate, felt hat down to his eyebrows, pulling at his braces to adjust the sagging trousers. ‘Come on you lot,’ he admonished the bedraggled onlookers. ‘How about these rabbit traps or that there box of pony shoes.’ But times were tough; few people were bidding. Next day, after friends had been in to help themselves, Fred and Jim carted truckloads of junk a few miles down the track and dumped it in a gully.

‘What ever happened to Grace Darling?’ I asked my mother years later, but she couldn’t remember. Nowadays when I look back, I see Grace Darling lying somewhere across that black soil plain, still holding her lantern.

Parts of this essay first appeared in the memoir ‘Vanished Land’, published in 2014.

Messages

I never knew what to expect when I picked up the heavy receiver of the antiquated telephone attached to the wall in our hallway. My mother took many of the coal orders, but from the time I was able to answer the phone, I relayed messages to her and later was able to write them in my childish hand in the untidy message book.

Small orders came from householders in town who needed coal for their fireplaces, their fuel stoves and their laundry coppers. Conversations went something like this:

‘That the coal mine?’

‘That’s right.’

‘Mrs. Mingay ‘ere. Tell yer dad I need quarter of a ton, an’ I don’t want none of them big boulders.’

‘Yes Mrs. Mingay. I’ll tell Dad when he gets in.’

Large orders came from Tamworth, twenty-eight miles away, from the Power Station, the hospital, the butter factory and Fielders Flour Mill where they made the bread. There were calls from mine inspectors and the NSW Government Railway’s head office, and the NSW Coal Board in Sydney. The Coal Board always wanted the coal production figures for the week. I’d say in my best seven-year-old voice (as my father had instructed): ‘The output was the same as last week.’

Sometimes there were calls from truck drivers – those hard-working, easy-going, likeable men who drove the fleet of battered and unreliable coal trucks: Bedfords, Whites, Internationals and Macs. Some were ex-army vehicles, for it was only a few years after World War II.

I had little knowledge of the workings of trucks, so I passed on messages, sometimes with little understanding, but often with some merriment. The calls varied:

‘Tell yer Dad me engine’s buggered, just outta Currabub.’

‘Got a punsher an’ me spare’s ‘ad it.’

‘Me muffler’s busted. Sounds like a flamin’ tank.’

‘Blew me gasget’, ‘Think it’s me pistons’, ‘Stripped me gears’ and one day ‘smashed me sump on a bloody tree stump’. I kept careful records in the message book.

There was one particularly memorable call:

‘’Ello. That the coal colliery?’

‘Yes,’ I said.

‘It’s Bill ‘ere. Tell yer dad I done me big end, out by the cemetery. I’ll sit ‘ere and wait for a tow.’

‘Right-o Bill. I’ll tell him as soon as he comes up from the pit. You’re not hurt?’

‘Strewth no! Jus’ blew up.’

I finished the call and carefully replaced the receiver. Before I could write anything in the book, the image of the overweight and balding Bill with his exploding big end got the better of me. I just couldn’t stop laughing.

Keep Out

1953

Remember when we went to live in Tamworth, and you said we were going to explore that haunted house up the top of the road? Old Mr. Hill lived at the back there somewhere. We used to see him galloping his horse and sulky down the slope with all the kids hanging on, and Mrs. Hill petrified beside him. He’d be shouting, ‘Shut up you bastards!’ at the kids. But we hadn’t seen him for ages, had we. You thought they’d gone away, so we walked up the road after school. You read out the notice painted on the old piece of tin nailed to the front gate: ‘Private. Keep Out’ so we went round the back and scrambled through the thorny hedge. I got scratched on the arms and the face, but you said, ‘Come on, don’t be a baby.’

The wooden house was derelict. My father always said it had never seen a coat of paint in its life. I could see the grass and weeds growing up between the floorboards of the back veranda. The back door was chained with a padlock, but you kicked it, and the padlock just fell off, and the door flew open. You went in first, and the floor rocked up and down when you stepped on it. The place was empty and dark with cobwebs and dust. I remember those old portraits in curly gold frames still hanging on the wallpapered walls, all flowers, and the chair with the broken leg lying in the middle of the room and that old chamber pot full of soot in the fireplace.

‘Look in here!’ I said, but you said, ‘Shhhhhhhhh!’ and we heard someone crashing through the undergrowth somewhere down the back, then ‘Clear off out of there you bastards!’ from a distance. ‘Quick!’ you said, and I tried to open the front door. It was locked, but you managed to heave open the front window. I didn’t like cobwebs and spiders, but you said, ‘Come on, scaredy cat’. You gave me a leg up and pushed me over the splintery window sill. I fell out onto the veranda. ‘Run!’ you said as you climbed out too. We clattered down the front steps into the jungle and fought our way through the thorny hedge. Old Mr. Hill was shouting ‘Get the hell out of there!’ at the back door, but we were taking off for home down the gravel road.

Mother was in the front garden pruning roses. ‘Don’t stop,’ you said to me as we streaked by. We thought Mr. Hill was charging after us. ‘Don’t wave. Don’t let him know where we live!’ and we kept running – past Mrs. Chaffey’s and round the corner into the back lane, then into our garden through the back gate. ‘Now don’t you go tittle tattling to Mum’ you said when we’d stopped puffing.

‘I saw you girls tearing past this afternoon,’ Mother said later when we came in for tea. ‘What was all that about?’ ‘Nothing,’ you said as you spread the Vegemite on your toast. I just pushed the spoon right down inside my boiled egg . . . Remember?

—Elizabeth Thomas

.

Elizabeth Thomas is an Australian, born in inland New South Wales before the end of World War II. Her professional life has been devoted to music education. She studied at the Sydney Conservatorium of Music before taking her Education Degree in music from London University in 1973. She initially taught in England. On returning to Australia, she taught at all levels over the next thirty five years, from preschool to tertiary (the latter in the 1980s at the Tasmanian State Institute of Technology, now part of the University of Tasmania). She was involved in the formulation and writing of a new school music curriculum for the NSW Department of Education during the early 1980s. In the last twenty years she has run her own private music studio in Sydney. Over the years she has published (in education journals, music teacher and parenting magazines) material on child development and music, and aspects of music pedagogy. Her final work in this field was a regular essay in the journal of the United Music Teachers’ Association of NSW between 2005 and 2012. Creative writing and poetry have been important leisure activities since childhood although publication was never in mind until the completion of a memoir, Vanished Land, published in 2014.

.

.

Such fine writing!

Thank you, Cynthia.

And thank you dg for your encouragement!

The honour is mine/ours. The work is wonderful.

Many thanks for your comment, Cynthia! Much appreciated.

Enjoyed reading your story, I was under the impression Grace Darling was Australian but I was wrong, even though when in England some time ago there were banners celebrating 100 years of Surf Life Saving Clubs claimed to be originating in Australia due to her saving lives in the surf.

that was such interesting reading can relate to many parts of it love story’s from old home town many great story’s dad and Aunt’s told me.