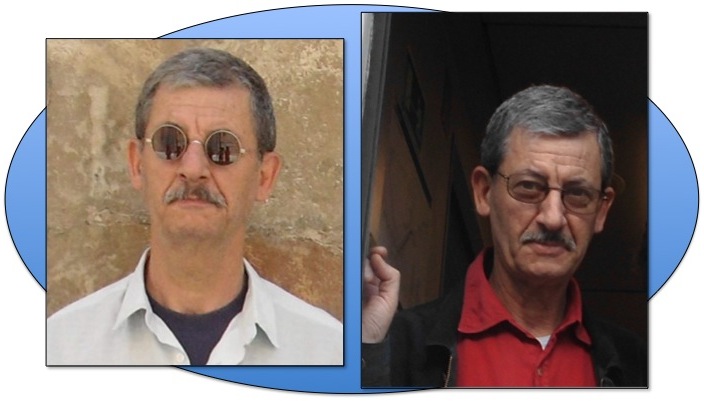

Vibrantly alive with the ancient spirit of the Mediterranean world, Rossend Bonás Miró is a Catalan poet, traveler, and teacher. For decades he has worked as a translator, interpreter, and lecturer in many countries, including Lebanon, Iraq, Egypt, Morocco, and Spain’s Ebro Delta region. Bonás is also the cofounder—along with fellow Catalan poet Arnau d’Oms—the pen name of Joan Vernet i Ribes (1952-2014)—of the independent press Els llibres del Rif (Rif Books). This press has been the imprint for several volumes by both poets.

Bonás published his first book of poems Preuat ostatge de les ciutats d’Orient (A Precious Hostage from Eastern Cities) in Barcelona in 1975. Another book of his poems El Emir de Tortosa (The Emir of Tortosa) (2003) was printed in the southern Catalan city of the same name where he lives when he is not making one of his regular trips to villages in the Moroccan Rif and Atlas Mountains. In fact, Bonás says that each of his books has been printed in a different city. Other volumes of poetry over the years have included Tothom ho sabia (Everyone Knew It) (1986) and Mercader d’essències (Essence Merchant) (1992). Summertime 2015 finds Bonás in northern Morocco, editing his forthcoming book of poems Perdut en la gentada (Lost in the Crowd), due to be printed in Tangier.

An artist of eclectic interests whose mission is to help build bridges of cultural understanding, Bonás uses both his Catalan given name Rossend and his adopted Arabic name, Rashid––as well as its Catalan cognate, Raixid.

In addition to his numerous books of poetry, Bonás has also collaborated on the creation of an illustrated Spanish-Arabic vocabulary book for students, about which he and the other authors write: “We hope that this book can be another channel for improving communication and understanding to build with the inherent richness of diversity, a better world where respect and peace hold sway.”

His ideals and poems echo the compassionate spirit of the great medieval Sufi poet Ibn Arabi (1165 – 1240) of Murcia, who wrote:

My heart has become capable of every form:

it is a pasture for gazelles and a convent for Christian monks,

a temple for idols and the circling pilgrim’s Kaa’ba,

the tables of the Torah and the scrolls of the Quran.

I follow the religion of Love:

whichever way Love’s camels turn,

that is my belief and the faith I keep.

In addition to a body of poems fascinated with the human spiritual journey towards union and understanding, and the non-human life of creation and the natural environment, Bonás is also a student of art, history, and culture both traditional and contemporary. He publishes his articles regularly in Fotent’s Blog (https://fotent.wordpress.com/). A son of Iberia, he is naturally fascinated with the intersection of European and Arabic influences that informs Spanish history, as shown in recent posts about the aesthetic power of Islamic art; the Spanish outpost city of Tétouan on the shore of North Africa; and the powerful, geometric compositions of glazed tile work of al-Andalus, ancient decorative art that influences Spanish and Portuguese design sensibilities down to the present day. Other postings by Bonás have focused on such important Catalan artists as the painter Joachim Patinir (1480-1524) whose landscapes were influenced by Hieronymous Bosch; the photographer Francisco García Cortés (1901-1976) who was a correspondent for the EFE Agency in Tetuan, a graphic collaborator on Diari d’Àfrica and an official photographer for the Spanish High Commission in Morocco; the great artist Antoní Clavé (1913-2005), a master painter, printmaker, sculptor and stage designer; and the painter and poster artist Josep Renau (1907-1982). Bonás’ fascination with the specific personality of different cities is evident in a recent post he wrote about the poetic symbolism of windows, with photographs of the many beautiful and different styles of windows in his city of Tortosa. His love of people and places also inspires a keen, clear, critical voice concerned with the problems of multinational socioeconomic policies that degrade life for many and prevent cultures from living healthy, progressive lives: https://fotent.wordpress.com/2015/04/26/la-menaca-del-sistema-economic-neoliberal/

As his friend and collaborator Arnau d’Oms (Joan Vernet i Ribes) said about him:

“Rossend Bonás’s poetic work goes hand in hand with his life, and thus, he has written poetry in the same way that some trees drip sap, and others provide us with lovely shade, while others give elderflower to clear our sight.

His books, published outside of commercial circles, are like rare jewels. Unusual discoveries. Simple, yes, but illustrated or designed by other artists.

Bonás is Catalan from Catalonia, where most people are not of any single race, although he claims to be among those with the deepest roots in this small country of transitions and permanences, with Iberian, Roman, and Saracen roots.

In his own style, he again mixes the unimagined with the unthinkable, the sacred with the profane, and recreates that time when the southern lands of Catalonia were Muslim and the northern frontier of Al-Andalus.”

On the matter of poetic composition, Bonás himself states: “The first raw material of poetry is sound, and that sound causes the reaction in the human brain. Over time, the reader knows that poetry, to capture all its nuances, should be read aloud. Or rather, should be recited or declaimed.” However, he affirms, there are those who read silently and “delight in pure literary love of the word, of the prosodic devices, of onomatopoeia, repetition and polysyndeton.” Either way, as far as the poet’s role in this relationship goes, Bonás contends that “When you finish a poem, you lose it, it’s no longer yours, you relinquish your authority over it to whoever reads it.”

In that spirit this article presents a generous offering of Bonás poems, selected by the poet himself, in their original Catalan and translated into English, which should provide readers with a splendid introduction to the verses of this timeless, visionary seeker.

— Brendan Riley

Als seus ulls

veig pregoneses

que no sé si hi són

ni si altres les veuen.

I see her eyes

deep proclamations

so deep I doubt

nor know if others see them.

* * *

Aquest vent que apareix

i desapareix sense avisar,

com els mals moments arriba

i, al cap de poc, se’n va.

Però torna,

insistent i regular,

i un bon dia fa tombar

la fulla més resistent

de garrofer o d’alzinar.

This wind that appears

and disappears without warning

comes like the worst moments

stays a while, flows away

But it returns

regular, insistent

and on any good day

it comes to tumble

the most resilient leaves

off the oak and carob trees.

* * *

Ígnia cabellera.

Encesa torxa

de rulls en cascada.

Volcànica lava.

El foc, semblava

que el diua per fora.

Però no, i ara!

És dins que cremava.

Her igneous hair

a burning torch

curling cascade

Lava from the volcano.

Like she was dressed

in a mantle of fire

But no, the perfect inversion

She was burning from the inside out

.

* * *

Wadi Lau I

Sota les palmeres de fulles remoroses

voldríem desxifrar el missatge del vent.

I a l’aigua de les sèquies, silenciosa,

espurnes de llum treu la lluna creixent.

.

Wadi Lau I

Under the palm trees’ murmuring leaves

we try to discern the wind’s message

And from the silent water pools

sparks of light engender the rising moon

.

* * *

.

—Si som en el temps,

que és moviment,

consiència pura;

si som consciència

en el còsmic moviment

i si és aquesta consciència

un privilegi…

¿per a què el vull, Senyor,

què n’haig de fer?—

rumia el pastor

mentre es bressola el ramat

amb la lenta i greu monotonia

dels cicles naturals.

—-¿I no haguera pogut ésser

consciència d’ase o d’ovella,

i no haguera pogut ésser

atzavara, poniol, insecte

o la primera figa

que l’estiu madura?

If we reside in time

which is motion,

if we are consciousness

in the cosmic movement

and if this consciousness itself

constitutes a privilege

Why do I desire it, Lord

What business is it of mine?

Thus wonders the shepherd

while the flock meanders

with the slow solemn monotony

of the natural cycles.

And would not have been possible

consciousness of donkey or sheep

and would not have been possible

agave, mint, and insect

or the first ripening

fig of summer?

.

* * *

.

El pecador, que no en tenio prou amb el perdó, demanava, a més a més, l’esperança.

¿O hauré de veure com m’apago,

trista, anònima i lentament,

sense tan sols el comfort plaent

de l’esperança, resignant-me,

com el ruc corbat sota sa càrrega?

.

The Sinner, Not Satisfied with Being Forgiven, Asked For Hope As Well

Or will I have to pretend how I fade,

sad, anonymous, and slowly,

without even the pleasant comfort

of hope, resigned like the donkey

plodding beneath its heavy load?

.

* * *

.

Exposició col•lectiva d’Art basada en poemes de R. Bonàs

Aquesta exposició és el resultat d’una proposta en la que 12 artistes fan una lectura gràfica dels poemes de Raixid Bonàs.

1

Seguim en aquest món serè

enduts per remolins de passions

banals i no gens descabellades,

en un estiu accelerat que,

tot just començat, ja és ple.

2

La ment, ¿pot fer avinent

l’oblit de mi mateix

amb el ‘jo’ treballat

tan àrduament?

3

Seguint els cagallons

de les cabres de l’Olimp

pujàvem pels camins

flanquejats de margallons

baladres, atzavares i pins.

4

La realitat dels fets tossuts i quotidians

desafia, il•lògica, candor i fantasia.

5

Si simple titelles som

de la gran representació

al Teatre Universal…

moveu-nos els fils, Senyor,

que puguem representar

moltes funcions

en Vostre Honor

i per a satisfacció de tots!

6

Com descriure el dolor tens i larvat

després d’una separació definitiva?

S’endu el vent el lent treball dels anys

i l’íntim plaer de la mútua companyia.

.

Collective Art Exhibit based on the poems of R. Bonás

This exhibit is the result of a proposal in which twelve artists perform a graphic reading of the poems of Rossend Bonás.

1

We endure in this serene world

driven by whirlwinds of banal passions

still sane not at all hare-brained,

in an accelerated summer,

one freshly inaugurated

yet already teeming full

2

Can my mind be called

to recall my self-inflected

oblivion with the oh-so

arduously overwrought “I”?

3

Following the dark pellets dropped

behind by the goats from Olympus,

we pushed upwards along the paths

flanked closely by palmettos

oleander, agaves, and pines.

4

The reality of all

our stubborn daily deeds

illogically defies

candor and fantasy.

5

If we are merely marionettes

of the great representation

at the Universal Theater…

move our threads, Lord,

so we might mirror

a purposeful multitude

of movements

in Your Honor

meant to satisfy all!

6

How to describe the tense

and tightly wrapped pain

a dark cocoon

after a definitive separation?

The wind carries away the work of years

and the intimate pleasure of mutual company.

— Susana Fabrés Díaz & Brendan Riley

A native of Barcelona, Spain, Susana Fabrés Díaz is a teacher and artist. She wrote the first, working draft of these translations from the Catalan.

Brendan Riley has worked for many years as a teacher and translator. He holds degrees in English from Santa Clara University and Rutgers University. In addition to being an ATA Certified Translator of Spanish to English, Riley has also earned certificates in Translation Studies and Applied Literary Translation from U.C. Berkeley and the University of Illinois, respectively. His translation of Eloy Tizón’s story “The Mercury in the Thermometers” was included in Best European Fiction 2013. Other translations in print include Massacre of the Dreamers by Juan Velasco, and Hypothermia by Álvaro Enrigue. Forthcoming translations include Caterva by Juan Filloy, and The Great Latin American Novel by Carlos Fuentes.