.

The pop machine

MY FATHER OPERATED a garage in the small prairie town of Bredenbury, Saskatchewan, pop. 500 or so, located just off the Yellowhead Highway 30 miles west of the Manitoba border. The garage was low and squarish, with a huge sign mounted high on the front that read ‘Hi-Way Service,’ navy blue letters against white. I don’t know how much that sign set my father back, but I know it was too fancy by half for a small-town shop in the sixties. A year or two after the sign went up, the new highway went in, skirting the town entirely. The unlucky Hi-Way Service now fronted on a low-traffic graveled street little different from any other street in town. Over time, the blue letters weathered to a colour close to purple.

Inside the garage, over to one side, was a pop machine built like a chest freezer. Sometimes, not often, on a hot day I would slip into the garage, into dimness after sunlight. The clank of a tool hitting a workbench, the pffft of an air hose, the earthy smell of oil. I would make for the pop machine, use all my muscle to push open the lid, and peer over the side at the rows of glass bottles. They hung in their separate metal tracks, NuGrape, Orange Crush, Seven-Up, Club Soda, Coca-Cola, suspended by their bulbous little chins, their lower parts immersed in a bath of ice-cold water. I could reach way, way over, feet lifting off the floor, and plunge my hot hand into the cold bath. Once in a long while, or maybe once, period, my father found a dime and slipped it into the coin slot, and I slid a bottle of NuGrape along its track and out past the metal guard. Ten cents bought one release of the guard and the satisfying slap as the metal fell back into place after the bottle came out. An opener was mounted on the front of the machine, a pry mechanism, and below it a cap-catcher shaped like a tiny pregnant belly. I held the bottle, sliding-wet from its cold bath, and my father gripped it further up, along its tapered neck, and helped me lever off the cap. It fell, clink, against the other caps inside the little belly. I have never lost my appreciation for the earth-sweet smells of gas and oil. I wasn’t really even supposed to be in the garage.

Hi-Way Service before the sign

Hi-Way Service before the sign

The pasture

I was a town kid, but Nickel’s pasture was my little bit of wild. I could get there by walking: across a gravel street, across the corner of a neighbour’s triangular lot, across a ditch. Not there yet: across the gravel road that used to be called a highway, across another ditch, and finally along a lane. I liked to sit in the pasture at the bottom of a little draw, low enough that I couldn’t see a single house or car or shed. The pasture was rimmed by scrubby bush: chokecherries, saskatoons, spindly poplars. Down in the draw I was in the Wild West, a place I knew from TV, in all its black-and-whiteness. Kicking around the house we had an Indian-princess hairpiece—a pair of braids made from three pairs of old nylon stockings. Bobby-pinned into my hair, the braids hung on either side of my white and pink and freckled face and draped onto my shoulders. I don’t recall if I was wearing the braids on the day I’m thinking about now, the day I was frightened by my own heartbeat. Crouched in the draw, summer warm on my hair, sun frying my freckled nose, I listened to the silence of that small world. And then I heard a beat, relentless, rhythmic. Indian drums! From the stand of poplars over there! I froze for a moment; then I ran home fast, listening as the drumbeat sped with me, inside my chest.

Years later, my sister and I and the girl from across the street put the pasture to another use. Hanging from a nail on our kitchen wall was a tin matchbox holder, and in it was a box of Eddy’s Redbirds. The tips of the matches were banded blue and red and white, the colours of the Union Jack. We’d grab them by the handful, couldn’t stop ourselves from licking them to taste the naughty taste. We’d make off with them to light our little fires. In the pasture we pulled together small, dense stooks of dry grass, lit them, and watched as they went poof, and flared and died. One day the flare didn’t die. We high-tailed it away and waited for a grown-up to notice the grass fire. Eventually, a grown-up did. The volunteer fire department came out in force to quell the flames, and we were either not found out or were silently excused without a fuss.

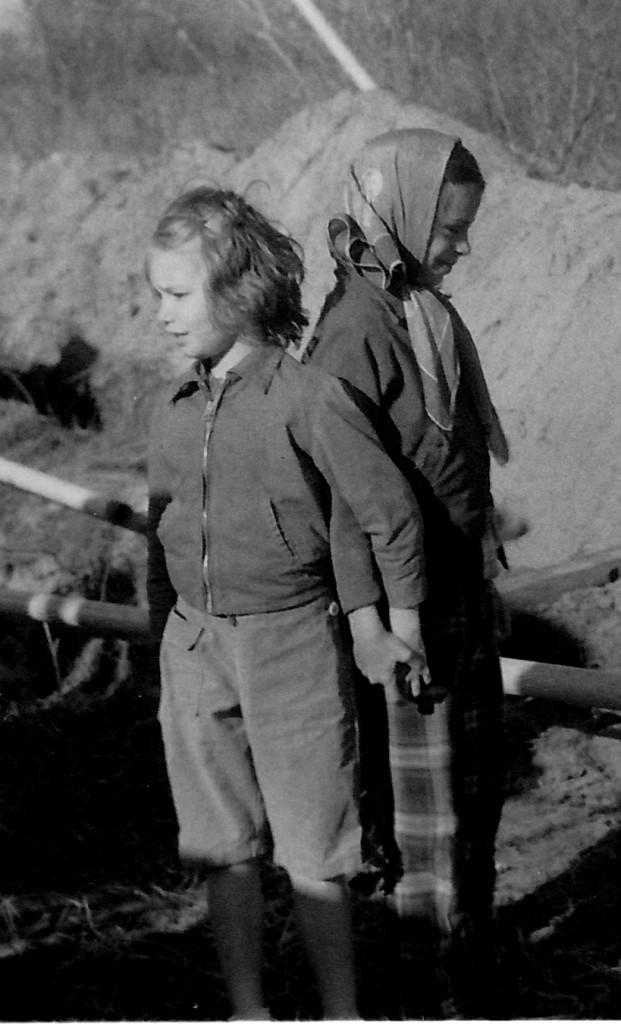

The Little Kids (Leona on the left)

The Little Kids (Leona on the left)

.

The nuisance grounds

Small-town Saskatchewan kids were free-range kids in the sixties. We could walk along a country road to what we called the nuisance grounds, about a half a mile from town. On one excursion, we three girls found skin magazines, and we ripped out pictures of partially naked women and folded them into our pockets. Were we ten or so? In the heat of summer days, among the reek of rotting left-behinds, we found other memorable junk—one day the remains of the combination mailboxes the post office had disposed of after the conversion to keyed boxes. The old boxes had metal fronts, about five inches wide and four inches high, each with two concentric dials on the front that reminded us of the safes we saw on “Get Smart.” These metal doors were still attached by hinges to wooden drawers, and the drawers slid in and out of what remained of the wooden framing that housed them when they were still in use. Some of the frames were open at the top, and we could see inside the guts of the mechanisms well enough to figure out the combinations by watching closely as we turned the dials. Every kid needs a place to store her secrets. We had a wagon with us (of course), and we each took home a mailbox or two. We memorized the combinations, closed the open tops with nailed-on boards, and hid the dirty pictures inside.

The Red Thing

We four sisters shared a bedroom. Two sets of bunk beds. I assume that The Red Thing, which stood at the foot of one of the beds, began as a display stand that came to the Hi-Way Service in the course of business, and once the product it displayed was sold out—oil, antifreeze, wiper blades?—my mother or my father carried it half a block to the house so it could be put to a new use. It was made of heavy-gauge wire, say three-eighths of an inch in diameter, and the wire was coated with a red material, silicon or plastic or some such. It had two or three shelves, and the back and sides were an open grid of wire. Into and onto this rig we piled books, teen magazines, comics, puzzles, paper dolls.

—Where’s my Nancy Drew?

—It’s on The Red Thing.

The Secret of the Old Clock, Donna Parker, The Curly Tops Snowed In (my first-ever hard-cover book, which my mother brought home from a magical place in Regina called The Book Exchange), Heidi, Treasure Island, Little Women, Call of the Wild. The bottom shelf was low to the floor, and the broom wouldn’t fit underneath; you’d have had to move the entire rig to sweep there, and so when I sat in front of it to sort through the sliding stack of Archie comics and colouring books I could see the dust curls underneath. We weren’t much for housekeeping anyway. Words were the thing.

We discovered The Red Thing was sturdy enough, and freighted with enough printed matter, that it could counterbalance the weight of a child hanging upside-down off the front of it, feet up top, hands grasping the sides halfway down. Every kid needs a members-only club, and every club needs a pledge. I remember one of my sisters, face blossoming red, hair dangling inches from the dust bunnies, reciting “I will hang upside-down, I will hang upside-down, I will hang upside-down for my club, the upside-down club.” I can recall no function of the upside-down club other than hanging upside-down.

One evening—I think I was about nine—I heard my three sisters laughing in the bedroom, and I walked in and grouched at them, because what could be funny when my mother had just told me we were about to lose the house, and we’d all be out in the snow with our furniture by Christmas? Snow falling on the bunk beds and The Red Thing, I supposed. And on all the books, the ones on The Red Thing and the others, hundreds of them ranged on shelf after shelf in the living room, the ones I had to stand on the back of the sofa to reach.

I don’t know how my mother succeeded, ultimately, in saving the title to the house. A lot of yelling went on, those years, and we girls managed sometimes to tune out the specifics. I do think it must’ve been my mother who saved the title. My father was smart in his way, a small-time genius as an inventor, mechanic and electrician, but he had no head for business or law, and he was so good at avoiding the tough questions that he knew how to leave mail unopened for years if he didn’t like the address on the upper left corner of the envelope. Long after my parents died, going through old files, I came across a sheaf of papers that had to do with the house, the garage, the courts: eight letters from the sheriff, seventeen from various creditors, fifteen notices to do with unpaid taxes, and three to do with court proceedings. A note in my mother’s handwriting attests that a letter from one creditor remained unopened for seven years; it was old enough that the mailbox the postmistress would have sorted it into would have been opened by combination rather than key. Through the years when all that was going on, I would sometimes sit in front of The Red Thing and open my copy of Heidi and bring it to my nose and sniff the pages. The smell of ink and binding glue and pressed paper would call up a feeling that I want to describe as friendship. I still do this with books; I still am surprised by that same feeling, whether or not I know beforehand that it’s what I’m looking for.

The garden

In the early years, we grew vegetables in the vegetable garden. One summer my next-older sister and I—we were the “little kids” and the two oldest were the “big kids”—were paid 88 cents each for a couple of days of hand-pulling portulaca and pigweed free of the stubborn clay. Why 88 cents? Because the general store was advertising an 88-cent sale and as part of this special occasion they’d brought in toys, a rare addition to their stock. When my sister and I walked into the store clutching our coins we learned that most of the toys were in fact priced at $1.88 or $2.88. We did each come home with something cheap and plastic and unmemorable, I’m sure we did, and I’ll bet we loved these things for as many days as we would have loved the more expensive bits of plastic. But weeding—we hated it. The garden became a wonderland only after my parents lost interest in using it to grow vegetables. In the area where a different family might have planted potatoes and beans and corn, my sister and I dug an enormous hole, an underground fort. Evenings, I would scratch my scalp and have my fingernails come away full of grit, a satisfying feeling, evidence of a day well spent. We dragged old boards from here and there and laid them across the top of the hole, and we crouched inside amid shadows and candlelight. The smell of a candle burning inside dirt walls gave me a thrill I felt low in my tummy. A finger in the flame, how long can you hold it there? Or drip some wax into the palm of your hand and feel the bite. The small rituals of our club of two in our safe little hideaway, built too small for grown-ups. We were the bosses down there. We owned the place.

—Leona Theis

.

Leona Theis writes novels, short stories, memoir and personal essays. She is the author of Sightlines, a collection of linked stories set in small-town Saskatchewan, and the novel The Art of Salvage. She is at work on two other novels and a collection of essays. Her essays have appeared in or are about to appear in Brick Magazine, Prairie Fire, The New Quarterly and enRoute. She lives in Saskatoon, Saskatchewan.

.

.

I love this piece, Leona! And your prize winning essay, “Pathologies of the Heart,” which I just read in The New Quarterly. I’m so glad to see your writing in Numero Cinq, and grateful to have first met you in these online pages!

Hi, Kim. Thanks so much! We’d have met no doubt, but later rather than sooner. Lovely that it happened here.

Oh Leona, this is wonderful. Thank you. I laughed and my eyes leaked a little as well.

Your memories, so solidly evoked have triggered a waterfall of my own.

Including the taste of those matches… And the blush of grassfires lit “by accident.”

Fantastic work.

Really good images evocative of a free range childhood!