Granma Nineteen and the Soviet’s Secret succeeds both through its deconstruction of the adventure story and in its full embrace of the genre … one can only hope that more of Ondjaki’s work finds its way through the translation process. His is a voice the entire world should have the pleasure to experience. — Benjamin Woodard

Granma Nineteen and the Soviet’s Secret

Ondjaki

Translated from Portuguese by Stephen Henighan

Biblioasis

192 pages ($18.95)

ISBN 978-1927428658

.

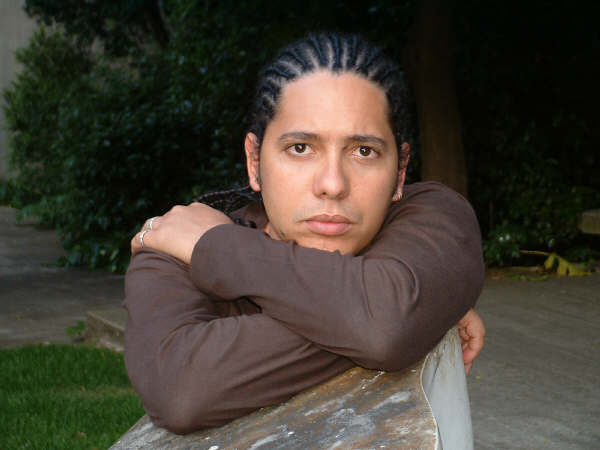

Angolan author Ndalu de Almeida, who writes under the mononymous pen name, Ondjaki, is something of a literary wunderkind: at 36 years of age, he has already published 20 books, won the José Saramago Prize for Literature, and been named one of Africa’s best writers by The Guardian. And yet, though celebrated throughout his homeland, Europe, and South America, he remains relatively unknown in the English-speaking world. This is unfortunate, for the newly released Granma Nineteen and the Soviet’s Secret, a devilishly simple-yet-sturdy tale of childhood and revolution (and just the third work of Ondjaki’s to appear in English), proves how behind the curve we English-speakers are: so often doused by literature hampered by the overly serious, Ondjaki’s writing, full of humanity, vivacity, and character, is a whimsical breath of fresh air.

Skillfully translated by Stephen Henighan, Granma Nineteen is set in Luanda, Angola in the 1980s, years after Angola’s independence from Portugal, but firmly entrenched in the country’s long civil war (which mostly occurs off-screen), and follows the daily lives of the residents of Bishop’s Beach, a community of mostly children and grandmothers. The story is told through the eyes of a young, nameless boy, as he and his friends (in particular Pi, or 3.14) wander the neighborhood and mingle with a menagerie of delightfully nicknamed locals—Comrade Gas Jockey, Crazy Sea Foam, Dr. KnockKnock—and equally interesting Soviet troops, who occupy the land in an effort to support the ruling political party. The troops are also overseeing the construction of a massive, rocket-shaped mausoleum to house the corpse of fallen President Agostinho Neto, and it’s this structure that sparks the novel’s conflict: rumors arise that the Soviets plan on dynamiting, or “dexploding,” several homes in the beachside community to expand the tomb. Hearing these whispers, the children decide to take on the Soviets, planning a secret attack on the mausoleum in hopes of driving the invaders away before their land is destroyed.

The novel opens in medias res: there is an explosion in Bishop’s Beach, and as the dust begins to settle, it appears as if the neighborhood’s giant mausoleum has started to crumble. From here, Ondjaki leaps backward in time to tell the story leading up to this moment. It’s a well-worn trick, the flashback, one often used in action films, where the viewer is immediately dropped into the action, only to then step back and learn about the situation. Adding to this, Granma Nineteen’s premise certainly reads as if it lifted elements from the plots of many children’s adventure films from the 1980s (think The Goonies, or Explorers, or Red Dawn). But what’s intriguing about Ondjaki’s story is how fully aware it is of these familiar tropes. Rather than existing as a paint-by-numbers adventure, the novels functions as almost a commentary on the formula, with Ondjaki’s narrator constantly referring to the films he and his friends take in at the local cinema as they plan their attack. These children know how movies work, and apply this knowledge to create an adventure. For example, the first time the gossip of dynamite being smuggled in by the Soviets is raised, 3.14 says, “In cowboy movies dynamite is for blowing up trains, houses or even caves, to find gold” (18). This reference to cinema continues two pages later, when the narrator spies on the mausoleum from his bathroom. He turns off the light to remain invisible to the outside world. “I’d learned this from a war movie,” he says (20).

By constantly having his characters live out and reference moments from their favorite films, Ondjaki’s narrative succeeds on two fronts: first, a steady verbal rhythm is created. The word “movie” appears 26 times throughout the thin volume, and with each mention, the reader is simultaneously transported back to the previous mentions (a flashback-within-a-flashback, if you will) while also propelled forward within the narrative. This creates a wonderful looping rhythm to both the piece and the language within. Secondly, these moments reinforce to the reader the fantasy that is the novel: Only in a film would a ragtag group of youngsters take on a military force with nothing but their wits and courage. And this is where Ondjaki’s flashback structure also helps cleverly underline the narrative as that of playful, rambunctious popcorn. Knowing the mausoleum will be ruined at the beginning of the story allows the reader to fully embrace the events that lead up to the explosion.

In using a child’s perspective, Ondjaki writes a political rally cry of a novel without ever having to dedicate space to heavy political rhetoric. Angola in the 1980s was a cog in the Cold War, but these ideas mean nothing to a child. As such, while Ronald Reagan is mentioned, it is through the beak of a parrot as the children launch their attack:

We ran forward, then went in stealthily along the side of the veranda so that Granma wouldn’t call us. The yard was dark. The parrot His Name shouted out to expose us: “Down with Amer-ican imperialism.” We made an effort not to laugh: the words came from a television commercial that hadn’t run in a long time. Just Parrot finished off: “Hey, Reagan, hands off Angola.” (143)

Instead of talking politics, then, Ondjaki’s protagonist and his friends stumble through their adventure chatting about the things that ring true to children: cheating in games, the proper way to make fun of a superior, and the queasiness of the fairer sex. These are children who threaten to “smash your face in” (36) one moment, and then barter the next, as in when 3.14 and our hero attempt to procure a pair of pliers from Madalena, another child:

“You guys…You talk and talk and you don’t say anything.”

“You’re the one who’s not replying.”

“What was the question?”

“The question was about the pliers.”

“There must be a pair in the toolbox.”

“You can’t just lend them to us?”

“‘Just lend them’? Just how?”

“Just like that.”

“And if they catch me in Granma’s stuff. Aren’t they ‘just’ going to give me a thrashing?”

“No, Granma will only give you a kind of thrashing.”

“I can go see if they’re there.”

“Thank you, Madalena.”

“What’s this thank-you stuff? Thank you is what you say to the Comrade Teacher in school. Here there’s going to have to be salt for us to eat with green mangoes.”

“But haven’t you got the key to the pantry?”

“No. It’s in the display cabinet.”

“And the key to the display cabinet?”

“It’s in Granma’s room.”

It was agreed: salt in exchange for the pliers. Later she showed us a huge pair of pliers with a plastic grip that would be great for cutting an electric cable. We had already seen this in movies and everybody knew that to cut electric cables you had to be wearing shoes, wrap the pliers in a piece of cloth and not have wet hands or feet. (39)

Ondjaki rarely employs dialogue tags in exchanges like this, which adds to the chaotic nature of the moment. This chaos highlights an interesting concept: The reader doesn’t really need to know when 3.14 or the narrator or Madalena is speaking, for in the land of children, it’s less about who is speaking, and more about the end result of the conversation. Want conquers all. And here, Ondjaki also returns to the motif of cinema, lending the dialogue an association with the rapid-fire tête-à-têtes found in the screwball comedies of Preston Sturges and Howard Hawks. Again, the escapism of the children influences their lives.

In the end, Granma Nineteen and the Soviet’s Secret succeeds both through its deconstruction of the adventure story and in its full embrace of the genre. Added to this are Ondjaki’s quirks—the children wonder if Crazy Sea Foam has a pet alligator, the titular grandmother earns her moniker after losing a toe—and his uses of magical realism—one of the grandmothers turns out to be a ghost—which combine to build a story unique in its straightforwardness. In finishing Granma Nineteen, one can only hope that more of Ondjaki’s work finds its way through the translation process. His is a voice the entire world should have the pleasure to experience.

.

Benjamin Woodard lives in Connecticut. His recent fiction has appeared in, or is forthcoming from, Cheap Pop, decomP magazinE, and Cleaver Magazine. In addition to Numéro Cinq, his reviews have been featured in Necessary Fiction, Publishers Weekly, Rain Taxi Review of Books, and other fine publications. You can find him at benjaminjwoodard.com and on Twitter.

/

/