Editor’s Note: Herewith, the opening section of Robert Day’s novel Let Us Imagine Lost Love, which we published in its entirety as a serial novel from September, 2013, to April, 2014. The novel remained online until August, 2014, at which point, as per our original agreement with the author, we deleted all the segments except for the first. We have left this opening segment, just as it was published, for your entertainment and to celebrate the amazing experience we had putting this book together. This was a first for Numéro Cinq, our first full length novel, our first serial novel — exciting times, wonderful experience watching the novel unfold month by month.

In the tradition of Charles Dickens and any number of 19th century novelists who wrote those triple-decker novels first published in serial form in magazines, Numéro Cinq today launches Robert Day’s new novel Let Us Imagine Lost Love, which will appear here in seven monthly parts. This is the long awaited follow-up to Day’s wondrous and acclaimed first novel The Last Cattle Drive; it’s not a sequel, but in Let Us Imagine Lost Love, Day returns to his native Kansas, of which he is a wry, witty and affectionate observer. His narrator is a book designer, who loves the jargon and paraphernalia of his profession, a man without a wife but a string of Wednesday lovers, his “Plaza wives,” he calls them. At his back, as we learn in the opening sequence, is a strong-willed Kansas mother who made him memorize three words a day and wouldn’t think of letting him go east to college (he ends up at Emporia State Teachers College). But this is vintage Robert Day: the humor is dry yet generous, the dialogue is laconic but rich with implication. You shouldn’t miss skinny dipping with Melinda or Tina, the narrator’s college girlfriend who would only begin to take her clothes off over the telephone (those innocent days). And stay tuned for the next installment.

dg

—

Part One: My Cosmic Smoke Signal

Since You Asked and I Promised: Here’s How It’s Turned Out

These days I design books. Gutters and “case backs,” “rivers” and “verso,” “quarto,” and “signature” are the nomenclature of my trade. Or were when I started. “Format” and “galley proof.” Pocket Pal and Rookledge’s Type Designers are my codices.

I understand I am un-hip in my patois, as if I were to use “Hi-Fi” instead of “stereo”—which I do. “Mono,” I am told by Lillian, my sister’s late-in-life daughter, is a disease. It used to be music as well: the kind that came from the lid of a forty-five record player: Memories Are Made of This. Scotch and Soda.

At first I worked at Hallmark here in Kansas City. Now I freelance. My Plaza apartment is my office. The Country Club Plaza, Kansas City, Missouri. Mr. and Mrs. Bridge’s domain. Calvin Trillin slurping a frosty at Winstead’s. Edward Dahlberg pissing and moaning about the city.

At Hallmark I designed “favorites:” 20 Favorite Poems by Shakespeare. 100 Favorite Love Poems. 50 Favorite Words of Wisdom. 100 Famous Quotations By American Women. I also designed “paths”: 50 Paths to Wisdom. 25 Paths to Bliss. No one suggested 50 Ways to Leave Your Lover. Or even one.

I was not cynical about such work then, nor am I now. When you grow up with webbed aluminum lawn chairs and a pedestal-mounted blue glass globe in your front yard, an Irish father who talked to himself but not much to anybody else (“I’m talking to a smart man when I’m talking to myself”), and a Polish mother who saved coins in Mogen David wine jars, you gain perspective. If my book buyers want their wisdom flush left in purse-sized octavos, who am I to judge? We all have our paths.

I design address books. I do not design novels. I design recording calendars, sometimes called “agendas.” I do not design memoirs (fictional or not). I do not design auto repair manuals. Or medical texts. I design exhibition catalogues: A Painter’s Room of My Own. Coffee table books: The Stalls of the Seine (into which I cut and pasted some of my own books that were—as far as I know—never there, unless you count them being vicariously there—which I do). More: Joyce’s Paris. Small Hotels of Italy. A Place in the World Called Seville. And once, a tiny duodecimo for autographs.

I win awards. I am well paid. I am praised for my “tailored elegance.” For “combining utility with beauty”: For “fusing” the well-known (a Degas auto point that looks like Allen Ginsberg as Allen Ginsberg got older) with an obscure Franz Beckman auto point.

Among my favorite projects have been two “Abecedarians.” One was about painting: M was for Matisse: with a young woman in an afternoon pose; a second was about writers whose pictures appeared like a water mark behind their letters with their text at the bottom: C was for Chekhov: “It was said that a new person had appeared on the sea front: a lady with a dog.”

But my favorites are “Blanks”— books with empty pages for memoirs to be written or diaries to be kept. Or not. I am Mr. Tabula Rasa of Kansas City. And other cities as well.

Over the years I have spread into various rooms: computers, scanners, light tables, and a recently purchased color copier configured to print and bind books. With that addition I am a one-man, limited edition, publishing firm: Blanche de Blank Books, the bit of French added for a bit of cache, if not for Stella Kowalski’s sister.

This week I am finishing a series of “Artist Blanks,” each with a picture or text as the cover: Van Gogh’s portrait on a sketch book. John Donne (I long to talk to some lover’s ghost who died before the God of love was born) for poets. Notes from Pachebel’s Canon (it’s in fashion again). I am trying to decide if Chekhov should be a short story writer or a playwright.

—Did you do this? my sister Elaine asked when she and her husband Gerhard had me for dinner.

It was a coffee table book that featured paintings of women in New York museums: Madame X from the Metropolitan, a Vermeer from the Frick. Picasso’s Two Nudes from MOMA. Others. I had been inspired by an old Playboy photo series: The Women of Rome (they were riding topless on Vespas); The Women of San Francisco (they were hanging out of both their blouses and the cable cars on which they rode).

—Not that you always “fess up,” she said.

—Yes, I said.

—Lovely, she said. I keep it out.

My sister’s diary, an early Blank of mine (a garden motif with both plants and flowers as a running head and end papers), also in the living room that night was (I took a peek) blank: Hours without alphabets. Days without words. Impatiens without patience. It was sitting next to another book I designed on the gardens in Tuscany, but since Elaine did not ask about either of them, I said nothing.

I like what I do. There is a pleasing philistine sensibility about a well- designed, large-format book that features the flora and fauna from the French impressionist period. The philistine sensibility is not in the book, but in the plush homes and apartments where Monet’s Water Lilies or Fantin LaTour’s Still Lives languish. I test my designs against the horizontal of coffee tables, not the vertical of bookshelves.

At first, I would use an alphabet soup of Bs and Es and Ts and Hs on the page to make sure the design was working, even if the book itself might never find work. For recent projects I have been using authors I am reading: Walker Percy, William Carlos Williams, Anton Chekhov. Today I used Joyce Cary: The Horse’s Mouth. Gully Jimson.

I could scan these texts, but when Chekhov goes up my fingertips to the radial nerve, then through the brachial plexus, he arrives at my temporal lobe with all his faculties in intact. Give me fifty words and I am the doctor in Ward Six. A hundred words later I am Doctor Chekhov. Five hundred (plus a pull of vodka), and I am Mother Russia. The transmigration of texts.

Before I send the final designs to the publisher I “delete” and “expunge” Gulley’s London, Percy’s New Orleans, or Chekhov’s Yalta. I don’t want my editors to know whose verbal masks I wear at work.

Nor do I want the finished book: my contracts specify that I shall not get complimentary copies, nor credited with the design. When I see my books I want it to be by chance, as in my sister asking: Did you do this? Or the other day in Barnes and Noble on the Plaza where I take coffee and browse:

—Lovely, isn’t it? said the elegant blond check-out woman when I bought a copy of my remaindered The Table of Chez Panisse. Then, looking at me, she said:

—You’re somebody, aren’t you?

—Yes, I said. She smiled, took a second look, but could not place me. It might come to her because Picnic is playing at the art theater nearby.

—I thought so, she said.

Serendipity is my favorite royalty. Even if I don’t make use of fortuitous coincidences. In this case the actor she has half in mind is fully dead.

—What are you working on now? Elaine asked.

Gerhard was in the kitchen with Rosetta (a cleaning woman we share) fixing martinis out of Sean Connery movies. I have agreed to come “a few minutes early to talk entre nous.”

About the time the martinis are to be wheeled in, my “date” will arrive—a woman my sister tells me makes her own sweaters. As the day has been surprisingly cool, she might be wearing one. The evening is one of Elaine’s attempts to “hook me up” (my niece’s language). Elaine wants me to “settle down” with someone “solid,” someone with whom we can all travel. I don’t travel.

—I’m designing an agenda for the Nelson-Atkins’s spring show. Also a book for a friend.

— It’s only August, she said.

—They need lead time, I said.

My sister studied me for a moment. She and Gerhard are on the board of the Nelson and she probably knows about the spring show and its featured painter. She is waiting for me to “fess up.” I don’t. I had expected she’d ask about the “friend,” but she seems to have been distracted.

—Anything else?

—Freelance proposals, I said. What would you think of a diary using Tom Lehrer Songs across the top: “It Just Takes a Smidgen to Poison a Pigeon.”

—Too mean, my sister said. Shame on you.

My sister has a “suppressed” smile; she holds her lips together and that makes the rest of her face—eyes, nose, ears—break into a bemused grin. She might have been smiling under her hairdo.

—How about an agenda of Keane women coupled with Rod McKuen’s poetry? I said.

—Very too mean, she said.

I don’t tell her that for my amusement I’ve designed both: The Vatican Rag with Paranisi prints; and The Shadow of Your Smile Meets the Windmill of Your Mind, using the big-eyed Keanes. They were practice for this very Blank which, when done, I will send it to Blanche de Blank Books. I knew I was on the right track when a cosmic high-sign smoke signal curled off my Latin language dialog dashes.

—Steve tells me the Keanes are in fashion again, said my sister just as their dog Precious limped into the room, came over to me, barked once and sat down.

—What’s the matter?

—She got a thorn in her paw this afternoon and we were waiting for you to take it out.

—Let me see, I said and made a rollover motion. It’s not a thorn but a piece of glass.

—Should I haven taken her to the vet? She’s afraid of the vet, she’s not afraid of you. It’s probably in her genes. And you know how to…

—Get me some Neosporin, tweezers, and a paper towel.

When Elaine returned, I took out the glass, cleaned the cut, and filled it with Neosporin—all the while Precious was calm, only barking once from her back at the syncopated chime of the doorbell.

—My hero, my brother, Elaine said as 007’s martinis were wheeled in.

•

The Go-Slow Guide to William Allen White’s Town

I had not been good enough in high school to go “East” for college. My father had hoped for a scholarship to Yale or Harvard: an Ivy League education is to a young man from Kansas what a rich marriage is to a young woman. It went unsaid that the young man in question was thought none-too-bright.

My father’s ambition had been fueled beyond reason because Steve had earned a scholarship to Princeton three years before, and a year later Elaine would win one to Vassar. As for my mother, she discovered that any college in Kansas had to take you if you had graduated from a state high school.

—I think he should stay in our domain, she’d say, using one of the ubiquitous words she was forever trying to teach us.

—He should go East, my father would say without—I would learn later—any sense of history or irony: “Go East,” you could hear him say summer evenings in our front yard as he drank his beer on one of the two folding aluminum lawn chairs he had arranged on either side of the glass globe.

—I think he should stay in our environs, my mother would say from her kitchen window as she did the dishes.

I was often talked about in the third person

The summer after my high school graduation, I lived at home, not being a bother to my parents—in fact being considerable help when not life guarding at the municipal pool.

When my mother had to stay late at the county office where she was a clerk, I worked through her Chore List: “Start potatoes at 350, scrub them smooth”; “wipe kitchen counter, make it sparkle”; “shake throw rugs, make dust flit”). I didn’t know what I was going to do with my life, but I didn’t fret about it. I didn’t hang around my room looking into a tank of goldfish.

I mowed the lawn, painted the basement walls, cleaned out the attic, hung laundry on the clothesline, and ran errands. I picked Elaine up at the airport when she flew back for a visit. Some days I fixed flats, pumped gas and changed oil at my father’s garage and filling station. There were evenings when I would help him restore an old Studebaker Champion convertible in which he had courted my mother.

—I bought it back, he would say routinely as we’d come into the shop.

At the swimming pool, I saved a boy out of the deep end bottom but never said anything about it until my father saw it as a news item in the local paper.

—Was that you? he said, reading the paper in his lawn chair.

—What? said my mother through the open window.

I was the kind of kid who did not explain himself. Apparently I was saving myself.

The evenings I had off from the pool, I ran a movie projector for Al Roster who owned the local theater.

—You see Melinda in the back? he said

—Yes.

—Watch Bones McCall slip his hand into her blouse.

I watched.

—Watch how Melinda takes a breath.

I watched. Melinda tilted her head back and closed her eyes. Bones stared straight ahead. The movie was April Love.

Later that summer I got a few dates with Melinda as she didn’t seem to be going steady with Bones. We’d take in a movie, and afterwards drive to Winstead’s on the Plaza for a hamburger, fries, and a frosty. I had a key to the pool so we’d go for a swim after it had closed.

Melinda wouldn’t skinny dip, but she’d pull down top of her bathing-suit. I watched the way the underwater lights sparkled and bubbled around her breasts; I watched the way the bubbles cleared, and in so doing revealed her.

—When are we going to meet your girlfriend? my mother asked.

—She’s not my girlfriend.

—What is she? asked my mother.

Instead of an answer, I told her I had been accepted at Emporia State Teacher’s College for the fall semester.

—William Allen White’s town, my father would say by way of explaining my fate to his customers. “Emporia,” he would say in the evenings polishing the blue globe with a clean red shop rag. “William Allen White’s town.”

—You’ll need a dictionary, my mother said. Pick three words a day, even if you think you know them. But not in alphabetical order. That way you won’t get bored. Open the dictionary, find a word, learn it, and then write it on a slip of paper. Like a bookmark. Do you know what domain means? Do you know what plethora means? You need to make up for the words you missed.

She was referring to a grade-school year when I was a sickly child with an acute case of tonsillitis (probably misdiagnosed, now that I know better) that resulted in earaches, high fevers and many days absent from class.

—Words make a life, my mother would say, as much a mantra for herself as “go East” was for my father. Words make a life, she’d say washing the evening’s dishes while drinking the last of her Mogen David. Do you know what divined means?

One night toward the end of summer, Al Roster came to the pool. The evening had been chilly and there weren’t many swimmers left. We were about to close. The manager had gone home. Al was waiting at the turnstile. We walked out and stood by my car—a used Ford that had been a family hand-me-down from my father’s garage.

—I’ll pay you a wage, said Al. No more hourly. Full time work.

He wanted to expand. He was going to buy a theater in Overland Park and, after that, one in Roeland Park. Someday I could have a “cut of the net.”

—There’s a future for you in movies, Al said. And plenty of Melindas to watch. What’s an education good for these days? Nothing but trouble.

He made a pair of binoculars with his fists and peered at the ground. —Plus all the popcorn you can eat.

That fall I drove to William Allen White’s town.

—Your grandmother was a teacher in western Kansas, my father said by way of goodbye.

—Teachers and government workers always have employment, my mother said. Don’t forget: three words a day from the dictionary I bought you. It’s just like mine, so we can keep in conjunction.

•

Bottle James

When I got Emporia I took a room with Hulga, an Estonian who lived in a house her contractor son had built with the idea she could rent rooms to college students. There were six of us. I lived in the refurbished garage with Bottle James, whose car was a floating couch of a blue, four-door Hudson Hornet. His real name is John Lee James, but he was called “Bottle” by the time I arrived.

—Hulga started it, he said. It’s because I booze. Want a pull? Vodka.

—No thanks.

Bottle James built sets for the college theater and he had remodeled the garage with bookcases and desks arranged throughout. But he didn’t use them.

—No books, he said.

—How so?

—Library. I have a place in the scene shop where I study. Most of the time I sleep there. I live on air. Air and booze. Want a pull?

—No thanks.

—I’m going to Hollywood, he said. One night I’ll be acting the star role for the set I’m building, and the director will come along with an actress he’s going to ball and hear me. That’s how I’ll get my break. Then I’ll ball the actress. In the meantime, use the place. I built it as a set for somebody who’s into books and desks and pads on desks—and those calendars you flip over for every fucking day in the week of your life. That’s not me. We split the phone bill. What’s that?

—A record player. Plays both thirty-threes and forty-fives. The speaker’s in the lid.

I unfolded it.

—You got forty fives? Don’t tell me you got Dean Martin?

I didn’t tell him I had Dean Martin.

—That your Hudson in the driveway? I asked.

—Yes. The last of its kind. Next year I’m going to take it to Hollywood to scout the place.

I put my mother’s dictionary (Webster’s New World, College Edition) in the middle of the desk by the window. I put out one of those calendars you flip over for every fucking day in the week of your life. I arranged my textbooks in the shelves. I became a student with ease: English, psychology, history, general science, I liked it. Especially History. And three words a day: enigmatic, penultimate, erudition.

•

I Have Never Married

From the balcony that runs the length of my Plaza apartment I can see south across Brush Creek to my sister’s house in the neighborhood of Paul Newman and Joanne Woodward—as well as Ernest Hemingway finishing A Farewell to Arms. East is the Nelson-Atkins Museum. West is the Kansas line. I cannot see the ten miles to our old house in Merriam.

To the north is Westport where the Santa Fe Trail started. By leaning over my railing I can see the Westport Inn (now called Kelly’s Tavern), and next to it Jim Bridger’s “historic” outfitting store. I am told that in the late nineteen seventies a cattle drive came in from western Kansas and wound up at Kelly’s. I doubt it. But I like to doubt.

I have never married. I have had—and am having—a series of Wednesday afternoon affairs. My Plaza wives. Nothing solid. No one with whom to travel. All married.

Not long ago, I bought a second apartment in my building. Across and down the hall. It is smaller. No balcony. Still, it is pleasant in its way.

I do not rent it, nor do I intend to. I have made it a showcase (complete with a stylish coffee table and two excellent end tables) for the books I have designed. I also arrange the gifts I get from my Wednesday wives: French jams and Spanish olives and Belgian chocolate truffles they buy me at the Better Cheddar and bring to our assignations. Soaps and body lotions from Williams Sonoma. Bottles of wine if they need aging. Tins of foie gras. Silk flowers. Provençal napkins, Sardinian grappa. What these women give me is their lingua franca for who they are; I know this, they do not.

•

A Guide to Housing, Circa 1960’s

Emporia was my father’s webbed lawn chair. There was an honest earnestness to the town, and to the college. The students were not worldly and not knowing so. The boys talked about cars and girls; the girls talked about boys and lipstick. Our education did not lead to an education. That year I found erudite in my mother’s dictionary (page 494) and thought that is not me (nor “not I,” as I would later learn). Only Bottle James complained of Dean Martin: The rest of us were happy with Ray Coniff and Johnny Mathis. We were provincial and didn’t know it. Nor the word. The Kingston Trio had not yet left the Seine. Joan Baez didn’t yet have a ribbon in her hair.

Tina, Hulga’s daughter, lived in an upstairs room of the main house. There was a rumor that her father was a Professor Humbolt who had died in bed with Hulga the night of Tina’s conception. You could see Professor Humbolt’s portrait in the History Department where each year at graduation a prize was awarded in his name. By the dates on the portrait, Professor Humbolt had been dead long enough to be Tina’s father. I never asked.

—Forget about balling Tina, said Bottle. Everybody’s tried. Me included.

—She dating somebody?

—It’s because her father had a heart attack getting laid by Hulga and she’s afraid.

—She’s afraid she’ll die getting balled?

—You got to be afraid of something.

Tina was tall, had brown hair, a thin-lipped smile, and walked with a slight bump and grind. Her hips seemed to be moving even when she was standing still.

—I’m afraid, Tina said.

—Of what?

—I don’t know.

—I do.

—What?

—You’re afraid of being naked in front of me.

—It’s just not right.

—You’re afraid of being embarrassed of me being naked in front of you.

—What happens if I get a disease? Or pregnant.

—You’re afraid that you don’t know how to do it.

—Do you?

—I have a plan.

—What?

By Thanksgiving, Tina would unbutton her blouse while we were talking on the phone, me in the garage, she in her bedroom a hundred feet away.

—Will you take it off?

—No.

My record player lid was singing “When I Fall in Love.”

.

—Mother says you have a girlfriend, my sister said when we were back for the summer. From Emporia.

—Not really. Sort of.

—Have you…

—We’re working on it.

—I was about to say: “Have you thought about bringing her home?”

—No.

We were sitting on our mother’s chartreuse couch; she was still at the Water Department; our father was at the garage putting chains on tires. Steve was spending Christmas in Cambridge working at a law firm. I had picked up Elaine from the airport two days before. My sister seemed different, but I didn’t say so.

When you are a young man trying to get used to your body and what it wants, it is difficult to understand how strangely you behave. Tina taking off her clothes at the end of the phone line would not be all that ”kinky” today (as in the bumper sticker I saw on an art student’s car the other day at the Art Institute: “It’s Only Kinky The First Time”). But sitting next to my sister it seemed something I should be ashamed of. Better to go swimming with Melinda. And since “kinky” was not in my mother’s dictionary, nor in the lexicon of the sixties, I could not name the nature of my unease. Nor, given my Wednesday wives, can I now.

—Are you in love? said my sister.

—No.

—I might be, she said.

—Have you…?

—I’m thinking about it, she said.

—Do you know about men? I said.

—I’m learning, she said. From you.

Before she flew back East, Elaine asked me to drive her to Winstead’s for a Frosty; then into the hills behind the Plaza on the south side where the expensive houses are. Our parents did not spend their Sundays “Wish Book” driving. But both Elaine and I had friends whose parents did, and one of Elaine’s high school boyfriends took her for such rides.

—Do you want to live in houses like this? Elaine asked me we curved among the lawn-clipped mansions of Mission Hills, then down toward the Plaza and past the house where one day Precious would need to have a gash cleaned.

—I don’t think about it.

—Really. Don’t you think about what you’ll be like when you are mother and father’s age?

—I don’t.

—How strange, she said. Is it because you boys are always thinking about girls? Not about getting married to them or anything like that. Not about houses where you’ll raise children. Just about girls…well, you know what I mean.

I had never heard my sister talk like this. I wondered if that was what was different about her. She had turned a corner at Vassar and ahead of her was life: a curved driveway sweeping through a manicured lawn. And for her, life was the future with the past going out of view in the rear view mirror of my old Ford as we drove toward home.

Then I said something beyond my years; even as I said it I knew I didn’t fully understand its implications.

—You don’t grow up all at once. It takes a lot of not growing up along the way to get there. I think the trick is…

Then I remember not knowing what to say next.

—Will you let me meet Tina? My sister asked as we turned back onto Johnson Drive toward Lowell.

—No.

—Then it’s not right, she said. For her or for you.

But this was after she had been silent most of the way home, and then said: “Turn here—” just as we reached Lowell, as if somehow I would not have known how to get to our house.

•

Swimming Pools and the Practice of Medicine

I completed my first year at Emporia and came home for the summer to lifeguard. Melinda did not. But there were other girls to take to the movies and then for a late-night swim. I tell my parents I am studying to be a high school history teacher.

—American history? asked my mother.

—Yes.

—Real American history? asked my father. With heroes.

—Yes.

—And your words? Three a day, said my mother. You don’t want to be a rube.

—I left the dictionary in Emporia, I said.

—We can share, my mother said.

—When will we meet your girlfriend? asked my father.

—I don’t have a girlfriend.

—Who do you talk to on the phone? asked my mother.

—A friend from college whose father was in the History Department.

Our words started with alacrity, propensity, and serendipity. A big week for the suffix.

•

Clarence Day and Berkeley: An Introduction to a Memoir

—Your uncle Conroy writes that he has a fellowship if you earned good grades in science, my mother said one day when I came home from the pool for lunch. It pays wages and you get college credit. My mother said this without much enthusiasm. She was holding the letter and reading it a second and third time.

Uncle Conroy was my mother’s older brother, a pediatric researcher of international fame. In the cultural gulf between our linoleum-floor life in Merriam, Kansas, and Doctor Conroy Watkins directing a celebrated pediatric research lab in Berkeley, California, there was a pleasing pride—as if in our small house on Lowell we had a first edition signed by Clarence Day.

—Let me see, my father said, who was home for lunch.

—At the University of California at Berkeley, said my mother.

I have an hour before I have to be back at the pool. After closing I am to take Muff LaRue to the Plaza. It is our first date. We will drive back to the pool for a swim. I am told by Bones she goes all the way.

—That’s what it says, said my father. A fellowship in Conroy’s research lab that could lead to medical school. He should get there as soon as possible for training.

—I don’t know that General Science counts, said my mother.

—Two semesters of A’s, my father said.

—He’ll need some lessons in manners if he goes, said my mother. Aunt Lillian will have more than one fork at dinner. They don’t “just eat” in a society like hers. They bring food to their mouth and not their mouth to the food.

I seem not to be present, even in the third person.

.

—I am going to be a doctor, I said to Muff LaRue as I unlocked the gates to the pool.

Muff dove in fully clothed and swam to the deep end. When she got there she pulled herself out and said if I’d turn off the lights she’d skinny dip. I flipped switches.

—I’ve never dated a doctor, she said. What kind of doctor?

She walked to the end of the low board. She took off her shorts and tossed them on the deck. Then she pulled her t-shirt over her head and threw it in the pool.

—A surgeon. I am going to Cal-Berkeley to be a surgeon.

I was treading water beneath her.

—I’m going to Sarah Lawrence to study classics. If you have a rubber I’ll do it with you, she said. A rubber and an air float.

She was trying to decide, long before Cybill Shepherd, whether to take off her bra next or her panties. Not that she is shy about it. Just before she dove in she laughed—a deep, throaty laugh.

.

It took me a few days to quit the pool and pack. I drove to Emporia to pick up the record player, records, clothes, and my dictionary. I told Hulga I would not be back in the fall. Tina had gone to western Kansas to visit her grandmother. Later that week, I parked the car at my father’s garage and took the bus to San Francisco. My uncle met me at the station.

—So you might want to be a doctor? he said.

—I don’t know, I said.

We were driving over the Bay Bridge toward the East Bay. You have to be a young man from a small Kansas town to understand how astonishing it is to see San Francisco Bay for the first time. There is nonchalance about its grandeur.

When I said I didn’t know if I wanted to be a doctor to one of the most famous and accomplished physicians in America, a man who had probably made special arrangements to get me a fellowship I did not deserve, it sounds, even at this distance, something Californian-sixties: Mellow. Really, man. Yeah. Wow. Far out. That’s not what I meant. Perhaps I thought—as we crossed the Bay Bridge to the East Bay—that if I couldn’t be a doctor like Uncle Conroy, I didn’t want to be a doctor. I’d like to think that now.

—I don’t mean. . . I said as we drove up Grove Avenue past the lab where I would be working.

—I understand, he said. Don’t worry about your future. It is always there.

—Thank you, I said.

—That is the hospital with which the lab is associated, my Uncle said as we passed by. And that’s where you can get a cup of coffee.

On the other side of the street was an all-night diner, its neon sign proclaiming: MEL’S.

From Grove we drove into the Berkeley Hills behind the Claremont Hotel to my aunt and uncle’s house overlooking the Bay. It was where I lived until just before the fall semester began when I rented a room on Derby.

•

The Thor: An Owner’s Manual

The other day Elaine and I drove to our home in Merriam. I don’t have a car, so we used hers. The house is twenty minutes west across the state line, 505 Lowell.

On previous trips we noticed the place was vacant; drapes pulled, its lawn not mowed. I am thinking about buying it but I have not told my sister. It might take me awhile to find the owner. There was no “For Sale” sign.

505 Lowell is a small ranch affair with a one-car garage. There is a basement my father refinished so my brother and I could have rooms of our own. They were on either side of the furnace out of which heating ducts ran upstairs. When my mother wanted to talk to us she would speak into one of the floor registers; the one in the kitchen went to my room; the one in the living room worked for Steve. When my mother made a mistake it was our joke to say “wrong number” and beat on the heating ducts. My sister lived upstairs and down the hall from our parents.

Steve and I had small windows onto the lawn. After a few years our father refinished the front part of the basement with brown vinyl paneling, making it into a “rec room.” There was a ping-pong table, a sofa on which Elaine necked with her boyfriends, and the portable forty-five record player that each of us would claim and that I took to Emporia: “Summer Place.” “Misty.”

We sold the house after my mother died; Steve wanted the money; my sister had married and moved to Mission Hills. I wanted to keep it but didn’t say so.

The glass globe is gone, but the Christmas tree my father planted when Elaine was born is still there—now more than forty feet tall. The wooden awnings he made to celebrate Steve’s birth are gone and the gravel driveway has been blacktopped, but as far as I know they are the only changes in all these years. Precious’ great grandmother is buried in the backyard.

Like the apartment, I would not rent the house. I’d furnish it with a chartreuse davenport and matching end tables on either side. Webbed aluminum lawn chairs. Early Ozzie and Harriet. The Thor All Purpose Domestic Appliance. We could probably get most of what we need from yard sales. Or E-Bay, if I did the Internet. Elaine has the record player in her attic.

—What happened to his globe? my sister said as we turned down Lowell from Johnson Drive.

—I don’t know, I said.

—And the Thor?

—It went to the garage when he died, I said. It wasn’t there when mother died. I expect the new owner had it hauled away.

—I got a tree and Steve got awnings, my sister said. She leaves it unsaid that I got nothing.

Elaine and I have gone over all this before. The furniture of memories: familiar roads, familiar talk. The yard sale of our lives. The repetition is pleasing: even the pauses between us have been there before. I should do a Blank: Silences. Use stills from Woody Allen’s Interiors. Or Pakula’s Klute.

The Thor was a combination dishwasher, washing machine, vacuum cleaner, and clothes dryer. A round, menacing contraption, it was mounted on four hard rubber wheels that had to be locked before starting it. The lid looked like a submarine hatch; the body a tank turret. It took my father and two neighbors to carry it into the kitchen. It was our mother’s anniversary present. The following Christmas, he bought her a Western Flyer lawn mower.

Elaine and I have come to the end of Lowell and are making a turn down the hill at 52nd street. Some trips she asks about the Thor, other trips she talks about the glass globe. Because she has brought up both, I wonder if she senses I am thinking of buying the house.

—Do you remember when the Thor attacked us? my sister asked as we took a right turn up Newton to take a left on Johnson Drive past the corner where my father’s filling station had been, but where is now a visitor’s parking lot for our high school across the street. She has said this before.

—Yes, I said.

—Where did he get it?

—A friend of his in the military made them after the war, I said.

I have said this before.

We are a blank of silence the fifteen-minute length of Johnson Drive to Fairway Manor.

—I knew about you and Muff LaRue, my sister said as we crossed State Line road, then down Ward Parkway, along Brush Creek and into the Plaza.

Just as my sister and I repeat ourselves, it is also our routine to add something on our drives. Muff LaRue is what she has added. I am wondering what I should add. Not about buying the house, I decide.

—I’ll walk from here, I said.

Elaine has stopped at the corner of 48th street and Jefferson near the sitting bronze of Ben Franklin and across from a series of amusing busts atop an apartment building just out of reach of the “building covenant” of the Plaza. In recent days a local rapper of national fame has been chanting up and down the streets, and my sister and I see him heading our way, his spray-dyed red hair bobbing and jerking.

—Did you know I knew about you and Muff? she said.

—I did, I said.

But I did not. It is not that I lie to my sister, it is that. . ..well, what is it? She is literal and I am not. Some of my life needs to be fiction, and my sister is my best reader. I take that back: I am my best reader, but I need someone to doubt me. Present company excluded.

—I don’t believe you, Elaine said.

—Did you know about Melinda? I said.

—I do now, she said.

—Ben Franklin wrote an essay on the virtues of older women, I said as the rapper got closer.

It was what I have decided to add.

—Did he?

—Yes.

—Life comes around, Elaine said as I got out of the car. Muff LaRue has moved back to the Plaza and wants to meet you.

•

Design Proposal for Blanche de Blank Books: One of X

1. Title: My Cosmic Smoke Signal

A. Quarto: Neither paginated nor cut. Acid free paper.

B. Where a Section ends, there is a line drawing of your paintings (or segments of those paintings) mentioned in the text but scrambled so they are not where they are cited.

C. Typeface for text: Bookman (old style). 14 point.

D. Watermark: interlined subliminal text from California when facing text is Kansas, and vice versa.

E. Typeface for watermark: Book (Antiqua, Italics). 10 point.

F. Sample Text: “Clouds all streaming away like ghost fish under ice. Evening sun turning reddish. Trees along the hard like old copper. Old willows leaves shaking up and down in the breeze, making shadows on the ones below, reflections on the ones above. Need a tricky brush to give the effect and what would be the good. Pissarro’s job, not mine.” —Gully Jimson

G. Edition Binding. Title embossed in gold.

—Robert Day

Robert Day’s most recent book is Where I Am Now, a collection of short fiction published by the University of Missouri-Kansas City BookMark Press. Booklist wrote: “Day’s smart and lovely writing effortlessly animates his characters, hinting at their secrets and coyly dangling a glimpse of rich and story-filled lives in front of his readers.” And Publisher’s Weekly observed: “Day’s prose feels fresh and compelling making for warmly appealing stories.”

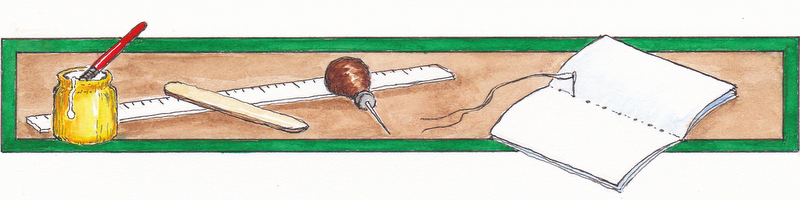

The novel banners at top and bottom are by Bruce Hiscock.

Absolutely delightful. More great writing by Bob Day. Looking forward to Chapter 2.

Chapter 1 – Pleasant and witty ,and shows the advantage of not “going east” to college. Can’t imagine where Chapter 2 will lead us.

Part One reads so well and is such a rich, multifaceted piece, evoking youth and the search for a personal path, small town America with the people who made it, endearing, real and somehow limited in their perspective by the very values that make them such special characters. While the narrative is full of life and the pace is great, there is retenue and reserve in the description, a lot is in between the lines. I read it with much pleasure and am looking forward to the future of Bob Day’s Charles Dickens career!

Bob Day is always entertaining; this maintains his high standard. It will be my first experience of a serialized novel, a reminder of the Saturday movies of my childhood which always included an episode of a “serial”, each episode ending as the bargirl with a heart of gold lies tied to a railroad track, train whistle in the distance, or struggling with a villain at a cliff’s edge, and a hero in a white hat riding hard to attempt a rescue. Day can be tricky, tho – enough readers for early chapters may lead to increased prices toward the end.

Dave Bacon

Rue Jacob, Paris