The first time I saw Ralph Angel lecture I was mesmerized and went away muttering to myself. He’d done something I’d never seen before. He had not only lectured about a poet and a form, but he had also ENACTED the form, the aboutness, in the PERFORMANCE of the lecture. In other words, to my mind he had invented a completely new way of lecturing, one which I have not yet been able to replicate myself (mutter, mutter). Although we do not have Ralph here to PERFORM this lecture, he does include an epigraph — the performance of the poem which is the poem — to remind us that this is his modus operandi and his way of conceptualizing both prose (lecture, essay) and poetry.

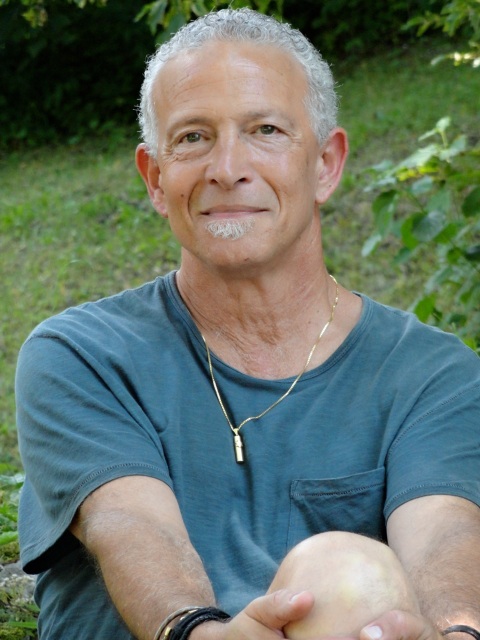

Ralph Angel is a dear and old friend and a colleague at Vermont College of Fine Arts and a graceful human being whose inveterate coolness does not hide the fact that he wears his love of beauty and art on his sleeve where it is a constant challenge to us all to do the same.

dg

§

It is the performance of the poem which is the poem. Without this, these rows of curiously assembled words are but inexplicable fabrications. –Paul Valéry

I was reading W. G. Sebald. I’d been reading his novels for a month or two. I was nearly finished with my fourth one, Austerlitz, the last of the four novels he published during his lifetime. And so I read the sentence:

When we took leave of each other outside the railway station, Austerlitz gave me an envelope which he had with him and which contained [a] photograph from the theatrical archives in Prague, as a memento, he said, for he told me that he was now about to go to Paris to search for traces of his father’s last movements, and to transport himself back to the time when he too had lived there, in one way feeling liberated from the false pretenses of his English life, but in another oppressed by the vague sense that he did not belong in this city either, or indeed anywhere else in the world.

And I stopped reading there, though it was early in the day, and I had no commitments or responsibilities to speak of. And the sentence itself was not of particular significance, I mean no more or less significant than any other deeply haunted, contextually complex, beautifully-composed ongoing sentence in this or any other Sebald novel. I mean there were only forty or fifty pages left in a book I was in love with, but I stopped there because I couldn’t bear to finish it. I mean, like I said, he only wrote four novels.

***

I thought back to Jose Saramago, the Portuguese writer I read and read before I started reading Sebald. And as with Sebald, I’d read little else than Saramago novels for months, literally. I thought back to the sanctuary of his language. Luxurious and running on, each sentence composed of a number of sentences strung together, wave after wave of solace and connectedness. And I longed for the comfort of “the Iberian peninsula breaking off at the Pyrenees from the European continent and drifting off to sea” because the language of the novel could contain and make perfectly believable such fantastical reality.

***

I love the true and beautiful lie of the novel. The illusion of completeness it provokes. The way it makes everything whole. Like a great poem, of course, a world unto a world unto the world of itself. A sanctuary I can withdraw to. A language that can nurture and sustain me.

And so I thought of Nicanor Parra and Rimbaud and Dickinson, the poets I’d been reading obsessively and compulsively before bathing myself in Saramago and Sebald. And that was my morning, lost in thought and longing and the uncomfortable sense that reading the last few pages of Austerlitz would be my ruin.

***

But the damage was done, I suppose. I finished reading Austerlitz because I could not bear the very idea of reading anymore. I was sick of it, frankly. I took long walks in the city. I visited a favorite painting or two. I rummaged through many stores. For the first time in a long time, I felt at home again in neighborhood cafés.

And I felt horrible, too. For it had been a terrible time, those last months. A horrible, wretched, awful time. But not so much. I mean everyone was more or less okay, everyone I knew, I mean. And I’d been luxuriating in the sanctuary of poems and novels, hadn’t I? And in such completeness I’d felt whole. Or I think I did. Everything had changed. That sense of wholeness was breaking down, breaking apart, like a tulip, before my very eyes.

It was as if I had just finished making another poem. Compose a last line, and then what? Nothing, that’s what. And nothing is the reason that whatever else my experience has taught me, it has taught that no matter how I think a poem can be made, it will get made some other way, if it gets made at all, and then I’ll be struck by amnesia again for the how many-eth time in my life.

And the truth of the matter is that for all those months of reading novels and poems and collections of poems, books of history and science and everything under the sun, I’d made nothing. Call it what you will, a period of transition, a blank page, a kind of exile.

All a writer wants to do is put words upon a page. I mean I spent time in my study each day, each day I was in town. And I read and read and read. And some days I put down a few lines, and felt good, and that was that. And maybe the next day I put down a few more lines, or not, that’s the way things go. But sure as rain I’d make the same discovery. The lines were bad. It was all crap. For months I’d failed.

You see, if I allow myself to finish something I tend to trust it, trust it enough even to put it into the world. And if I don’t, well, I throw it away, literally, into the garbage can where it belongs. You see, if some orchestration of language or other is important it’s inside me somewhere, sometimes for a long time, and it’ll make itself heard again when it’s good and ready.

***

One morning. like most mornings, I was sitting out back having a cup of tea and listening to the birds and the leaves of the trees. There is a lovely Florentine birdbath in the yard. Tucked away somewhat, among a loquat, an avocado and two eucalyptus trees.

And while drinking my tea, the birds, as they visited the birdbath, reminded me of Joseph Cornell’s “Dovecot” (American Gothic), a favorite of mine. It’s quite abstract, as are all the boxes that were inspired by Emily Dickinson.

Cornell’s dovecot is very white, or sun bleached, or whitely weathered somehow. Many of the arched entrances are still in tact. Of course the wood is old, and the paint, too, is old, and some apartments have long gone derelict and vacant. A small white ball is perched just inside a few of the entrances, like the fluttering dove or pigeon that surely lives there, or will surely pass through someday. They are, of course, the little balls, implacably what they are. The don’t look at all like eggs.

I went inside, of course. I mean I thought of Saramago. After an hour or two of searching, I read this passage:

For several moments [the two men] remained silent, then José Anaiço rose to his feet, took a few steps in the direction of the fig tree as he drank the rest of his wine, the starlings kept on screeching and began to stir uneasily, some had awakened as the men spoke, others, perhaps, were dreaming aloud, that terrible nightmare of the species, in which they feel themselves to be flying alone, disoriented and separated from the flock, moving through an atmosphere that resists and hinders the flapping of their wings as if it were made of water, the same thing happens to men when they are dreaming and their will tells them to run and they cannot.

It was, of course, a familiar landscape, the way landscape is huge, and it gets bigger and bigger, what with travel and change and moving around in one’s life. I think, in fact, that I carry my sense of place inside me. And it gets altered over and over again, and so too, therefore, does my sense of who I am.

It was a piece of something, that Saramago passage. A fragment. Like a construction site or a cathedral, the undulating surface of a river I walked along somewhere, a face that stood out among a group of faces at a crosswalk. It’s what I wanted. A broken tile.

It took me I don’t know how long to find a paragraph in Gabriel Garcia Marquez’s One Hundred Years of Solitude, a novel I hadn’t read in twenty years. It was only two sentences:

As soon as José Arcadio closed the bedroom door the sound of a pistol shot echoed through the house. A trickle of blood came out under the door, crossed the living room, went out into the street, continued on in a straight line across the uneven terraces, went down steps and climbed over curbs, passed along the Street of the Turks, turned a corner to the right and another to the left, made a right angle at the Buendía house, went in under the closed door, crossed through the parlor, hugging the walls so as not to stain the rugs, went on to the other living room, made a wide curve to avoid the dining-room table, went along the porch with the begonias, and passed without being seen under Amaranta’s chair as she gave an arithmetic lesson to Aureliano José, and went through the pantry and came out in the kitchen, where Úrsula was getting ready to crack thirty six eggs to make bread.

A few days later I found another sentence in One Hundred Years of Solitude that I wanted to hear:

‘Open the windows and doors,’ [Úrsula] shouted. ‘Cook some meat and fish, buy the largest turtles around, let strangers come and spread their mats in the corners and urinate in the rose bushes and sit down to eat as many times as they want, and belch and rant and muddy everything with their boots, and let them do whatever they want to us, because that’s the only way to drive off ruin.’

I thought of “The Dead,” the James Joyce story. But not the story. Not the whole. Just the last paragraph:

A few light taps upon the pane made him turn to the window. It had begun to snow again. He watched sleepily the flakes, silver and dark, falling obliquely against the lamplight. The time had come for him to set out on his journey westward. Yes, the newspapers were right: snow was general all over Ireland. It was falling on every part of the dark central plain, on the treeless hills, falling softly upon the Bog of Allen and, farther westward, softly falling into the dark mutinous Shannon waves. It was falling, too, upon every part of the lonely churchyard on the hill where Michael Furey lay buried. It lay thickly drifted on the crooked crosses and headstones, on the spears of the little gate, on the barren thorns. His soul swooned slowly as he heard the snow falling faintly through the universe and faintly falling, like the descent of their last end, upon the living and the dead.

I went back to Stevens. To the last stanza of “Man On the Dump”:

One sits and beats an old tin can, lard pail.

One beats and beats for that which one believes.

That’s what one wants to get near. Could it after all

Be merely oneself, as superior as the ear

To a crow’s voice? Did the nightingale torture the ear,

Pack the heart and scratch the mind? And does the ear

Solace itself in peevish birds? Is it peace,

Is it a philosopher’s honeymoon, one finds

On the dump? Is it to sit among mattresses of the dead,

Bottles, pots, shoes and grass and murmur aptest eve:

Is it to hear the blatter of grackles and say

Invisible priest; is it to eject, to pull

The day to pieces and cry stanza my stone?

Where was it one first heard of the truth? The the.

And to a fragment from Sappho:

…………………and I on a pillow

will lay down my limbs

I could no longer bear the sanctuary of feeling whole. It didn’t feel right. Without thinking about it or knowing what I was doing I’d moved away from that. I walked in my own dark. Every novel is a fragment, I thought. Every poem.

***

Another favorite Cornell box is titled L’Égypte de Mlle Cléo de Mérode: cours élémentaire d’histoire naturelle. It is lined with marbled paper. It’s made up of rows of glass bottles with glass trays and compartments along the sides. Everything there, and everything here, is in his exotic desert apothecary. “A layer of red sand with a broken piece of comb, slivers of plain and frosted glass, and a porcelain doll’s hand and arm broken at the elbow.” “A plastic disk and three tiny metal spoons.” “Plastic rose petals.” Each bottle is labeled. “Each label refers to an aspect of Egyptian life: Sauterelles refers to grasshoppers and locusts: Nilomètre is an instrument used to measure the Nile’s waters, especially during floods. Another contains a photo, set in yellow sand, of a woman with hair parted in the middle and pulled back into a loose bun; she wears a choker and a dress with a revealingly low neckline and puffed sleeves. She is Cléo de Mérode herself, as captured by Nadar and preserved in this bottle for eternity.”

All this stuff. All these things. Joseph Cornell understood that it was his job to walk the city, and to rummage through the fragments that are there, and to collect them, and that it was his job, too, to go back home and, in his quiet, to do the work, time and time again, in his quiet, to get things done.

***

I often wonder how we would live our lives as they were lived forever and ever before time was standardized and we became so enslaved to it. And when was that? A hundred and fifty years or so ago. For as with my sense of place, I carry my past and my present and my future inside me, and all of it’s fair game. I mean my life comes to me like that, doesn’t it, as a kind of ongoing dialectic. My imagination doesn’t unfold in any linear way, for example. And memory, too, is a collage at best, fragments of experience in hairline fractures of time. The present can be as impressionistic and surreal as dream. And who doesn’t sense profoundly one’s connectedness to a vast, immeasurable continuum. It’s wacky out there, in the world, but it’s precisely how we experience our lives, I think. In fragments and moments, in glimpses and strange, delicate solitudes. It’s what presence and immediacy are made of.

I don’t believe there is any such thing as writer’s block. All I know is that there are periods of time, and, at times, protracted periods of time, when I have to throw everything away. And if I can make a sanctuary of reading, of poems and stories complete unto themselves and, therefore, whole, I must make that which is not whole my sanctuary—its traces and glimmers, its countless fragments.

I remembered a few lines from Henri Michaux:

Draw without anything particular in mind, scribble mechanically: almost always,

……….faces will appear on the paper…

And most of them are wild…

So much for memory, I thought.

And then the last page of Anne Frank’s diary:

A voice within me is sobbing, ‘You see, that’s what’s become of you. You’re surrounded by negative opinions, dismayed looks and mocking faces, people who dislike you, and all because you don’t listen to the advice of your own better half.’ Believe me, I’d like to listen, but it doesn’t work, because if I’m quiet and serious, everyone thinks I’m putting on a new act and I have to save myself with a joke, and then I’m not even talking about my own family, who assume I must be sick, stuff me with aspirins and sedatives, feel my neck and forehead to see if I have a temperature, ask about my bowel movements and berate me for being in a bad mood, until I just can’t keep it up anymore, because when everybody starts hovering over me, I get cross, then sad, and finally end up turning my heart inside out, the bad part on the outside and the good part on the inside, and keep trying to find a way to become what I’d like to be and what I could be if…if only there were no other people in the world.

And that was that.

Just silence. I’d stepped into it again, before I heard it. Outside the sanctuary of books and things, I pace around. I don’t read anything. Outside the language of the worlds of others, and of their images, their chipped off fragments, their deadly shards and petals, I grow quiet. I don’t read anything. For days and days, sometimes, I don’t leave the house. I don’t read anything. I step out into the silence of my own darkness. And I can hear there. Just silence. And in silence, my own language returns to me. I feel euphoric. Mostly I’m just skittish. But I can hear myself, in my unknowing, word by word, line by line, and sometimes things get done.

Every novel is a fragment. Every poem. And every fallow period, too.

It’s what I do.

[Skittering]

There is no staying here

except we who are set apart and different

observe ourselves and say “Thank you, a coffee,

yes, and toast, too.”

This is tomorrow. Scissors

and silverware, a pencil on the table,

we have to keep escaping

always into something like a courtyard

where the salt breeze trembles with branches

and nothing has changed

for decades. No one is lost again

on the surface of the pool.

Then all of a sudden

I am as much as sitting at the desk

of a man bewildered by my being here

and by the clouds behind me

skittering across

the skyline, and maybe

somewhat shaken, too, it’s hard to say,

what with loneliness and

everything alive inside

fitting easily

into its metal frame.

You are the perfect distance

when I think of you

I can’t see down the road too far, thank God,

not all the time.

This late in the season

the promenade is nearly deserted,

its few words wandering aimlessly

here and there in the quiet

occurring just now.

Pigeons have battered

senseless the archways and the highest doors,

but my heart is not complaining.

That’s why, but never mind,

what I’m trying to say

makes faint scratching sounds

upon the paper,

and if the message is less than clear, tonight,

my love, please know

that I’m just a little

out of practice.

—Ralph Angel

——————————–

Ralph Angel is the author of five books of poetry: Your Moon (2013 Green Rose Poetry Prize, New Issues Press, forthcoming); Exceptions and Melancholies: Poems 1986-2006 (2007 PEN USA Poetry Award); Twice Removed; Neither World (James Laughlin Award of The Academy of American Poets); and Anxious Latitudes; as well as a translation of the Federico García Lorca collection, Poema del cante jondo / Poem of the Deep Song.

His poems have appeared in scores of magazines and anthologies, both here and abroad, and recent literary awards include a gift from the Elgin Cox Trust, a Pushcart Prize, a Gertrude Stein Award, the Willis Barnstone Poetry Translation Prize, a Fulbright Foundation fellowship and the Bess Hokin Award of the Modern Poetry Association.

Mr. Angel is Edith R. White Distinguished Professor of English and Creative Writing at the University of Redlands, and a member of the MFA Program in Writing faculty at Vermont College of Fine Arts. Originally from Seattle, he lives in Los Angeles.

“Just silence. I’d stepped into it again, before I heard it. Outside the sanctuary of books and things, I pace around. I don’t read anything. Outside the language of the worlds of others, and of their images, their chipped off fragments, their deadly shards and petals, I grow quiet. I don’t read anything. For days and days, sometimes, I don’t leave the house. I don’t read anything. I step out into the silence of my own darkness. And I can hear there. Just silence. And in silence, my own language returns to me. I feel euphoric. Mostly I’m just skittish. But I can hear myself, in my unknowing, word by word, line by line, and sometimes things get done.”

My wife and children have been out of town for a few days. For the first time in years, I’ve been alone and quiet. I have paced around. I have stayed alone in the house. What a gift, this essay. What a wonderful, unexpected song.

Oh, how wonderful this is. Thank you for publishing it. I would have loved to have heard it in person, but it is enough to read it and know I am not alone in that inbetween time, when words fail to flow, but longing and desire remain.

Was a cool lecture to read on an iPhone. The quotes not only heated up credibility in the speaker’s voice, which shared subjective reflections in an accessible way, thank goodness, they also created their own little world. Nice juxtapositions. Reading “Skittering” out loud, rhythm and attitude could be heard and felt, big time. What a voice. That quote, “If it ain’t got that swing, it ain’t got that thing,” came to mind. Because it was not a pissing contest, the lecture came across like a conversation with an old friend. Refreshing read, in my opinion, even after some erotic Verlaine verses. Gracias, mucho, Numéro!

Thank you, Ralph. Just lovely… Great to have you here at residency, albeit virtually.

Lovely.

True Ralph Angel magic–devastating and redemptive!

As I began to read the lecture, I had to fool myself into thinking that I was sitting in College Hall, hearing Ralph deliver those calmly broken tones, and then it started to matter less, and by the time I reached the Anne Frank passage, my gut was in my throat as my humaneness reminded itself that it’s right here.

When I first learned of Ralph’s work and poems, I didn’t get it. It seemed too lucidly emotive, too in touch with something that I’d dismissed in lieu of fireworks and forced abstraction. But after a workshop with Ralph, and a few conversations, I started to see how he approaches this life, and I knew that he was in tune with something vulnerable, precious, and genuine, and then his poems started to sing to me.

This essay is of wonderful. Thanks for sharing!

-Martin

Consoling and true and beautiful. Loved learning of Joseph Cornell–thank you!

This is so gorgeous. So many parts of the essay struck a personal chord with me. The writing is lovely but also cutting somehow. I’ll never think of writer’s block in the same way.

Then there was this:

“I love the true and beautiful lie of the novel. The illusion of completeness it provokes. The way it makes everything whole. Like a great poem, of course, a world unto a world unto the world of itself. A sanctuary I can withdraw to. A language that can nurture and sustain me.”

I haven’t ever found anything that so accurately and beautifully describes the allure of novels. The way you write is magical, the repetition, the insight, the imagery, it is all simply enthralling. This is one I can read again and again. Thanks so much for sharing this.

The discovering of fragmentariness within and as what appears whole gestures in the direction of Heraclitus, among others, and reminds one of the need to continue looking and searching. What-is-not is the turning around of what-is that never turns on itself. Something difficult to say; something essential. Following Kierkegaard, this will require silence.

Ralph, thank you. This essay is absolutely medicinal to me. I am grateful to have come upon it in a time of transition, my own lonely dialectic struggling to fit with its literary and literal surroundings. To read this attentive account of an instance amid your creative processes provides both comfort and inspiration, and the collage that assembles itself above is breathtaking.

Ralph, you sent me a link to this essay last summer when I emailed you feeling like a lost and defeated writer. I’ve read it so many times since, and most recently this very morning over coffee because the voice of doubt was infiltrating my good senses once again. I can no longer absorb your peacefulness, patience, and deep, quiet will to create in class; but, I am grateful to at least find your words here and the sound of your voice.

So every novel is a fragment. Every thought. Every poem. In acknowledging my own pieces, the pieces of my own ever-expanding internal landscape, I remember what you’ve said here: “I must make that which is not whole my sanctuary—its traces and glimmers, its countless fragments.” I try to embrace the “ongoing dialectic” so that I can keep believing in myself, so that I won’t give up.

Thank you.