A Partial History of Lost Causes (Dial Press, 2012), Jennifer duBois‘ highly praised debut novel, is the story of Aleksandr Bezetov, a Russian chess prodigy who comes of age in the late stages of the Brezhnev era and rises to prominence as a world champion before taking up the doomed cause of opposition to Vladimir Putin’s political machine. But Bezetov’s story is braided in with the story of Irina Ellison, a young American woman, doomed to a certain and early death, who has come to Russia trying, for one last time, to find meaning in her truncated existence.

Chess informs this story, not so much directly in its playing, but as a kind of metaphor for the complex and layered relationships and shifting dimensions of the real and the possible her characters, and through them, the readers, experience. The remarkable clarity of duBois’ writing — at all times, the reader is aware of all the pieces in play and their constantly changing situations — further strengthens this connection to the game. And yet, for all the ways in which she makes clear the architectural conception of her story, she still manages to infuse the gritty realities she depicts of Bezetov’s life in St. Petersburg in the late stages of the Soviet Union — the kommunulka with its shared kitchens and its black-clad prostitutes banging on the building super’s door, the furtive dissidents Aleksandr comes to share vodka and plot with in the bar called Saigon – with a luminosity that can fairly be described as magical.

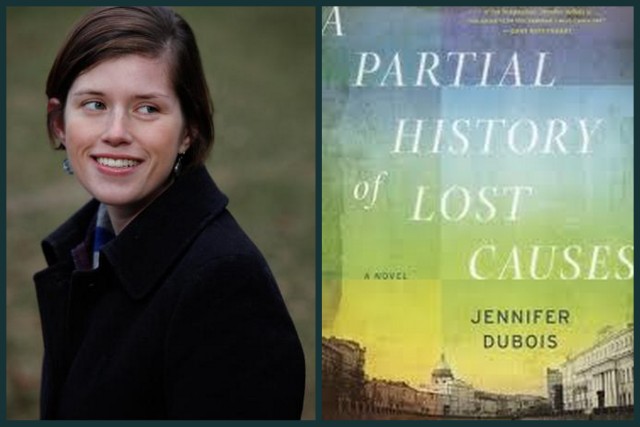

Read my review of the novel at the Washington Independent Review of Books. Author photo by Ilana Panich-Linsman.

—Rimas Blekaitas

§

Q: Vladimir Putin and his political machine figures prominently in the second half of your book. How do you go about including an active and controversial world figure into the fictive logic of your novel? What potential drawbacks did you think you wrestled with in doing this?

A: In my first draft of the book, I didn’t use Putin’s name, even though that was clearly who the character was meant to be, and some people thought this compromised the novel’s universe—the book is located very firmly in the realities of Russian politics and history, so it was pretty jarring for readers to suddenly enter an alternate world where some fictional creation succeeded Yeltsin. What was tricky about using Putin’s actual name is that Irina and Aleksandr basically manage to prove a conspiracy theory about him—a theory that in real life is widely held but absolutely unverified. So that whole plot line is a strange blend of pretty meticulously researched and faithfully reported information about real suspicions surrounding Putin, and then a wholly invented episode in which the characters confirm those suspicions. My worry wasn’t that I would be slandering Putin—it’s a work of fiction and he’s a public figure—but I did worry that some readers might come away from the book with a sense that Putin’s involvement in those bombings was far more certain than it actually is. But I think most readers kind of intuitively make a distinction between a political and historical landscape that’s grounded in reality and the fictional actions of made-up people, or even real people, within that landscape—for example, I’m reading Don DeLillo’s Libra right now, which is partly told from the point of view of Lee Harvey Oswald, and that difference is pretty easy to feel.

Q: There are many ways in which you, in keeping with your characters sensibilities, bring chess into the text. Here is one passage that beautifully brings several of your themes together:

“Walking along the river, he is struck again by the nearness of the future. It’s just beyond his vision, but it is there…He can sense it, like the sketched suggestion of an undiscovered country emerging in the mist, or the shape of an endgame materializing somewhere deep in his psyche.”

Although chess is important in your novel, little of the text goes into actual matches or chess situations. Did you, at one point or in earlier drafts, consider including more actual chess action?

A: I wanted very much to write about chess in a way that would feel convincing to a serious chess player but would still be interesting to a non-chess player, so I tried to narrate in detail only those matches that had a lot of emotional resonance for the characters. The match that makes Aleksandr a world champion gets a lot of attention, for example, as does his loss to the Deep Blue computer game; the moves in those games are described carefully, but you don’t need to be following them to understand the enormous amount that’s at stake for Aleksandr in those moments. I also tried to include a few details and in-jokes here and there that only serious chess enthusiasts would really enjoy—incorporating the actual moves from Kasparov’s matches versus Deep Blue and Karpov, putting important turns from other famous games elsewhere in the story (as when Aleksandr beats his instructor at the chess academy)—and I hoped that doing that would provide a layer of subtext for those people without making everyone else run away screaming.

Q: At your website, reader’s groups are invited to explore how your novel is structured like a chess match. In his preface to his own chess novel, “The Defense,” Nabokov calls the reader’s attention to certain moves he makes as an author. Do you find yourself feeling, as an author, that you are engaged in a chess match of sorts with your readers? How might this be true in your novel?

A: I don’t feel like I’m engaged in a chess match with readers, but I do think chess informs the book’s structure. Aleksandr and Irina’s relationship to the Putin regime is adversarial, of course, and there are moments when they make moves—and, at the end, sacrifices—that have a certain chess logic to them. The chapters alternate between Aleksandr and Irina’s points of view, which is a bit like a chess match; I realized after drafting the book that the characters are often doing things that are in some way thematically reactive or responsive to what the other one did in the previous chapter, even before they meet. Hopefully the plot’s unspooling feels like a chess game in that the events are unpredictable and at the same time firmly grounded within the logical parameters of what’s come before. Flannery O’Connor said that the best story endings are both surprising and inevitable, and it occurs to me now that the best chess moves probably are, too.

Q: What is it about chess, or any deeply absorbing and imaginative activity like it, that made you, as a writer, want to hang out with these chess playing characters of yours for the duration of a novel project?

A: I suppose there are some similarities between writing and playing chess—they’re both very solitary pursuits where you just kind of sit there consumed with something that’s essentially not real and anyone watching you would think you’re insane and/or inert—so maybe that’s something that drew me to Aleksandr, or that I understood about him, even though I’m not much of a chess player myself. There’s also something so interesting to me (and to everyone, I think) about people who are truly brilliant at what they do, and brilliant chess players are especially interesting because they often seem marked for brilliance in this way that’s very hard to understand—they often come to it as small children and then shape their rest of their lives around it. Gary Kasparov, for example, saw a chess problem in a newspaper at age four and somehow solved it, and that was it—chess was going to be his life. To me, this is so much weirder than some general athletic or verbal or mathematic aptitude that a child might grow up to develop in a variety of ways. Great chess players don’t just fall in love with the game—they somehow seem to already recognize it when they find it. Which is absolutely fascinating, in part because it makes no sense.

Q: One of the protagonists in your novel, the young American woman Irina, is also a member of a special club of sorts, the club of people who, having been given a diagnosis of an incurable and degenerative disease, know how, and roughly when, they are going to die. This knowledge has rendered her seemingly incapable of committing to deep friendship or love back home in America, even as she is searching for a way to grab some meaning for her life.

In the end, she does commit herself by self-consciously making herself into a sort of piece in a larger political game. In doing this, she is able to preserve, for the most part, her emotional remove.

There is this particularly powerful passage after she has made her big move in the game of Aleksandr’s politics and after she, herself has begun to show unmistakable signs of the onset of her disease:

“I lean back in my seat, and I feel the hoisting of the plane, its resilience against, the whirring cold, the forbidding blue. The pilot banks to the side, and we are casting an improbably detailed shadow on the countryside; we look like the approach of a mythical bird or an avenging god. Beneath us there must by the rifling of grass against soil, the frenzied roiling of pale-edged leaves. But we can’t see those things anymore.

“I think, although I am not sure, that my hands are shaking more than usual, beginning to thread forward of their own account ever more audaciously. I watch. I put my hand on the pullout tray, and they tremble and jump.

“But then again, maybe it’s not pathological. It could just be reverential. It could just be the beauty of the sky and the clouds-the miracle of morning, the heresy of aviation.”

The passage of course is made all the more poignant by what we already feel will inevitably happen to that flight. She has made herself into a chess piece in an endgame, an abstraction and that seems to be her way of mattering in this world. And yet, she does make a connection to another character near the end. Throughout the novel, you seem to play with moving between the real and direct and the abstract. Do you see this movement as one of the thematic elements in this novel?

A: When we meet Irina, she’s unable to find meaning in her life since she knows she’s positive for Huntington’s disease, and your formulation about the tension between the abstract and the concrete is a really great way to frame this problem. Death is a certainty for everyone and yet it’s also this really abstract thing that no one can actually wrap their heads around—really, we’re all just taking everyone’s word for it that this will happen to us. For Irina, this looming abstraction becomes much realer to her than the concrete elements of her actual life. She has terrible difficulty finding emotional connection in anything transitory (or perhaps it’s more accurate to say that she is too afraid and too stubborn to try)—and since everything is transitory for everyone, not just Irina, she’s got a real problem. But I actually see Irina’s ending as a rejection, or reversal, of this way of thinking; I don’t think she’s throwing herself into the abstract or the theoretical at all. Instead, I see it her actions at the end as her finally wholly investing in, and giving herself completely to, something that is very real, even though it’s nearly certain that what she’s trying to do won’t work (and it’s absolutely certain that, even if it does, she won’t be around to know it). To me, the ending is where Irina stops seeing everything in such abstract terms; the paragraph that you quoted is a moment where she is fully in the world and, finally, fully in her life.

—Rimas Blekaitis & Jennifer duBois

——————

Rimas Blekaitis recently completed his MFA in Writing at the Vermont College of Fine Arts. He works as a software engineer and lives in Washington, DC. Rimas writes poetry and fiction and is currently working on his first novel.

Jennifer duBois, born in 1983, earned an M.F.A. in fiction from the Iowa Writer’s Workshop after having completed an undergraduate degree in political science and philosophy from Tufts University. She was awarded a Stegner Fellowship at Stanford which she has recently completed, staying on at the university as the Nancy Packer Lecturer in Continuing Studies. Her fiction has been, or soon will be, published in Playboy, The Missouri Review, The Kenyon Review, The Florida Review, The Northwest Review, Narrative, ZYZZYVA, and FiveChapters.

Great interview, Rimas. I always love interviews where the reviewer really knows the book and has a lot to contribute. Many of your questions made me think of another chess themed book, The Chess Garden, and reconsider how certain elements might have reflected back to the game. I am excited to read this novel.

Turns out I have a copy of “The Chess Garden” on hand. I’m about a third of the way in on that one and liking it. I’d love to see your review of it, should you write it.

“The Defense” by Nabokov is definitely a “chess novel” if there ever was one. I have to confess that I think the screenplay adapted from the novel is actually better than the novel. It became the movie “The Luzhin Defense,” starring John Torturro and Emily Watson, both very fine. Torturro moves like a chess knight throughout…

I was very impressed – as if you couldn’t tell – by duBois writing – some of the passages (especially the ones I quoted) blew me away, in fact.