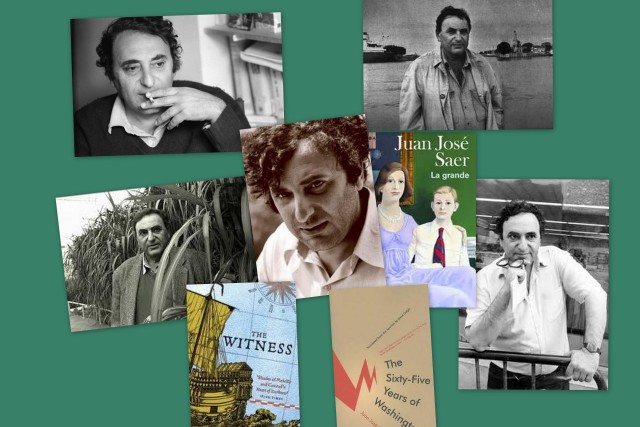

“There’s only genre—the novel. It took years to discover this. There’s only three things in literature: perception, language, and form. Literature gives form, through language, to specific perceptions. And that’s it. The only possible form is narration, because the substance of perception is time.” – Juan José Saer

Scars

Juan José Saer

Translated by Steve Dolph

Open Letter Books

ISBN-13-978-1-934824-22-1

A good novel does much more than communicate the events of a story. A good novel also reflects on itself. It dabbles a bit in theory, considers genre and rediscovers form. The well-written book, what John Gardner once called the ‘serious novel,’ borrows from the traditions of the past and gestures toward the future, often in destabilizing ways. A good novel refuses simplistic labeling because it relentlessly stalks the nature of things and, in so doing, it helps resuscitate the very reason we read (and write) in the first place: to render some insight into the ineffable, to close the gap between perception and thought, to diminish the emptiness between the world we experience and the world we feel.

Though built with the bricks and mortar of fiction—point of view, plot, character, theme, etc. — the very best novels are always interrogating themselves. They challenge. They provoke. They unsettle and confound. They ask questions about meaning rather than answering them. The reader willing to accept such books will often finish in a state of uncertainty, perplexed about what has just happened, about what has been read, about what it all means. But a door has opened in the reader’s mind, a nagging doubt exists that can only relieved over time, if at all, because the best books are always inviting us back, demanding to be reread, to be experienced again and again.

Juan José Saer’s novel Scars might well qualify as such as work. Set in the city of Santa Fe, Argentina, the novel is divided into four long sections, each narrated by a different character. Holding these disparate parts together are the events of May 1, Workers Day, a day when Luis Fiore, his wife and young daughter go duck hunting. It’s almost wintertime in the southern hemisphere, and a steady cool rain makes the hunting trip more dread than delight. Fiore and his wife argue all day, but Fiore bags two ducks anyway. He drives back into town, drops his daughter off at home and then stops in at a local pub with his wife. Inside the dingy bar, the ongoing argument between Fiore and his wife — an unnamed character with the mildly derogatory moniker Gringa—escalates. Fiore steps outside, points his shotgun in his wife’s face and pulls the trigger.

Part bildungsroman, part murder mystery, part Robbe-Grillet existentialist romp through a South American landscape, Scars refuses to be any one thing. The easiest comparison of its structure is with the game of Chinese Whispers (also known as Telephone). In the game, as in the novel, a single event is recounted by various witnesses, each with his own version. As the game and the novel unfold, the various perceptions skew the seemingly objective facts. What has been witnessed changes. As Joyce does with his theory of parallax, Saer shakes the reader’s sense of certainty. What is true? What really happened? It all depends on the position and inclination of the observer.

The novel’s opening section, titled “February, March, April, May, June,” introduces Angel, a young reporter for La Region, the local newspaper. Angel’s main responsibility is writing the weather headlines, a job he performs without actually checking the meteorology reports. “No Change in Sight,” he writes day after day. (Saer’s dry and subtle sense of humor peeks out often in the novel.) Angel lives with his young mother, a woman who struts around their small apartment in various stages of undress, more roommate than matriarch. While she goes out dancing, Angel rummages through her underwear drawer then masturbates in his room. Oedipal conflicts aside, Angel and his mother primarily argue over gin. In a brutal yet comedic scene, Angel beats the woman ruthlessly for polishing off his last bottle and not replacing it. “It’s my bottle. You drank my bottle,” he says, and then he proceeds to knock her senseless. This is truly one of the great dysfunctional relationships in literature.

But Angel is no mere brute. He reads Faulkner, Kafka, Raymond Chandler, Thomas Mann and Ian Fleming. A street-kid, raised by that promiscuous, alcoholic excuse for a mother, he survives by possessing an indomitable spirit and wit. You can’t help but root for him, out there in that big bad world. And at times, Saer’s world is both big and bad. The misery, layered thick in this novel, can make for a grim ambience. But Saer also works hard to tease out the inconsistencies, baffling us with magnificent bursts of light amidst such darkness.

Though sexually attracted to women, Angel is also the occasional lover of a ruthless judge named Ernesto (more on him below.) After the murder and Fiore’s suicide (spoiler alert: at the inquest, Fiore jumps from the window of the courthouse in front of Angel and the judge), Saer provides one last spellbinding twist in this opening section, a twist pulled straight out of nineteenth century St. Petersburg. Angel falls into a feverish fugue state, reminiscent of Raskolnikov’s post-homicidal fever in Crime and Punishment. Wandering around the streets of Santa Fe, Angel runs into his double, a man alike in appearance, dress and action. In a lovely passage, Saer describes the moment of recognition.

It was a young man, wearing a raincoat that looked familiar. It was exactly like mine. He was coming right at me, and we stopped a half meter apart, directly under the streetlight. I tried not to look him in the face, because I had already guessed who it was. Finally I looked up and met his eyes. I saw my own face. He looked so much like me that I started wondering whether I myself was there, facing him, my flesh and bones really holding together the weak gaze I had fixed on him. Our circles had never overlapped so much, and I realized there was no reason to worry that he was living a life forbidden to me, a richer, more exalted life. Whatever his circle—that space set aside for him, which his consciousness drifted through like a wandering, flickering light—it wasn’t so different from mine that he could help but look at me through the May rain with a terrified face, marked by the fresh scars from the first wounds of disbelief and recognition.

So much for the opening act.

§

“The singular aspect of the game is its complexity,” Sergio Escalante says, describing the game of baccarat in the book’s second section. Conjuring another character from Dostoevsky — this time Alexi Ivanovich from The Gambler — Sergio is an inveterate gambler. He gambles and wins, gambles and loses, gambles and gets arrested. He gambles away his money, his friends’ money, his fourteen-year-old housecleaner’s money. Sergio gambles with a monomaniacal passion. The forays into philosophy on baccarat make up the richest writing in the book. Sergio is the consciousness of the novel. Saer’s ruminations about the game are thoughtful, elegant and unsettling. Though the subject appears to be baccarat, he might as well be talking about the novel, or about life itself. “It (baccarat) precludes all rational behavior, and I’m forced to move through its internal confines with the groping, blind lurch of my imagination and my emotion, where the only perception available to me passes before my eyes in a quick flash, when it’s no longer useful because I’ve already had to bet blind, and then disappears.”

If Sergio is the consciousness of the novel, then the judge, Ernesto, is the book’s demonic soul. He suffers from metastatic misanthropy. Ernesto appears in the third section, and though he represents the system of justice, he hates people — all people, good and bad, guilty and innocent. He shows up late for work, shuffles his schedule around to suit his whims, and refers to other people as gorillas. There’s almost nothing human left in him. He would be utterly vile except for one thing: Ernesto is translating Oscar Wilde’s The Picture of Dorian Gray. From within the rubble of his miserable existence rises Ernesto’s work. The translation of Wilde beats like a thready pulse, barely circulating his humanity. It’s not much to go on, but the translation sections complicate the reader’s reaction.

This raises an interesting question: Is Saer evangelizing some form of literary salvation? Is he saying that even the worst among us might be saved by books? Consider that the only character who is not literary in taste or inclination is Fiore, who kills his wife, jumps out a window and orphans his only daughter. Maybe he should have read more?

Saer did much of his writing in Parisian exile. He renders his homeland with precise details and images as only an estranged citizen could, at times producing a landscape so precise, so accurate, that the technique becomes, well, awkward, in, yes, that Robbe-Grillet sort of way. A reader (like me) unfamiliar with the city of Santa Fe and the Littoral region of Argentina is left to wonder why he writes multiple passages in the Ernesto section with the monotonous certainty of a GPS navigation system. “I cross the intersection of still on 25 de Mayo to the south, and everything is left behind. On the next corner I turn right, travel a block, then turn left onto San Martin to the south.” The exile yearns for home, so he recreates the world he left behind even in the most mundane details, in the left and right turns of his characters as they travel from one place to another. Saer is remaking the map of his home.

The novel closes with thirty-three pages from Fiore’s point of view. This section covers only the span of one day, the day of the hunting trip and the murder. We don’t travel too deeply inside the murderer’s consciousness. He mostly narrates the events in a detached dramatic soliloquy. But we feel his agony. We see the pressure mounting. All day his wife badgers him, relentless in her infliction of misery, to the point of literally shining a flashlight in his eyes as she berates him over and over again.

— Turn off that flashlight right now, I say

— Turn off that flashlight, Gringa, or I’m going to shoot you, I say.

She laughs. I cock back the hammer, ready to pull the trigger—the metallic sound is heard clearly over her laughter, which for its part is the only other sound in the total silence—and the light turns off. But the laughter continues. It turns into a cough. And then into her clear voice, which echoes in the darkness.

— Help me pick up all this dogshit, she says.

Life has indeed become a pile of dog shit for Fiore. By the time he pulls the trigger, we are simply relieved to be done with this menacing woman. And yet Fiore loves his wife. She is not without her charms. Her pain and extreme anxiety emanate like the beams of the flashlight which she uses to torment her husband. “And I realize I’ve only erased part of it,” Fiore says at the end of the book, “not everything, and there’s still something left to erase so it’s all erased forever.”

The wounds in this novel run deep. Each character is scarred in his or her own way, and the novel ends without any indication that they may ever heal. The haunting image of Fiore’s orphaned daughter lingers long after the final page. In one brutal act, the little girl lost both her parents. What world awaits her? What horrible scars have been inflicted upon her? “In this respect, all the bets in baccarat are bets of desperation,” Sergio says. “Hope is an edifying but useless accessory.” A sobering truth, perhaps, but it’s an earned one, a conclusion that resists simple formulas and summary. There are no easy answers in Scars. There aren’t even easy questions.

—Richard Farrell

——————————–

Richard Farrell is the Creative Non-Fiction Editor at upstreet and a Senior Editor at Numéro Cinq (in fact, he is one of the original group who helped found the site). A graduate of the U.S. Naval Academy, he has worked as a high school teacher, a defense contractor, and as a Navy pilot. He is a graduate from the MFA in Writing Program at Vermont College of Fine Arts. He is currently at work on a collection of short stories. His work, including fiction, memoir, craft essays, and book reviews, has been published at Hunger Mountain, Numéro Cinq, and A Year in Ink anthology. His essay “Accidental Pugilism” (which first appeared on Numéro Cinq in a slightly different form) was nominated for a Pushcart Prize. He lives in San Diego with his wife and children.

See also Richard Farrell’s review of Saer’s The Sixty-Five Years of Washington and an excerpt from that novel here.

excellent review, thanks for taking your time to do. Your review for me echoed many of my interpretations with this book,,, your review was like an echo of my take on book